Abstract

Background

Intrapartum drugs, including fentanyl administered via epidural and synthetic oxytocin, have been previously studied in relation to neonatal outcomes, especially breastfeeding, with conflicting results. We examined the normal neonatal behavior of suckling within the first hour after a vaginal birth while in skin‐to‐skin contact with mother in relation to these commonly used drugs. Suckling in the first hour after birth has been shown in other studies to increase desirable breastfeeding outcomes.

Method

Prospective comparative design. Sixty‐three low‐risk mothers self‐selected to labor with intrapartum analgesia/anesthesia or not. Video recordings of infants during the first hour after birth while being held skin‐to‐skin with their mother were coded and analyzed to ascertain whether or not they achieved Stage 8 (suckling) of Widström's 9 Stages of newborn behavior during the first hour after birth.

Results

A strong inverse correlation was found between the amount and duration of exposure to epidural fentanyl and the amount of synthetic oxytocin against the likelihood of achieving suckling during the first hour after a vaginal birth.

Conclusions

Results suggest that intrapartum exposure to the drugs fentanyl and synthetic oxytocin significantly decreased the likelihood of the baby suckling while skin‐to‐skin with its mother during the first hour after birth.

Keywords: skin‐to‐skin, epidural, fentanyl

Background

A substantial body of research, including a recent Cochrane review 1, demonstrates that positioning a newborn skin‐to‐skin during the first hour after birth has beneficial effects on the health of the baby and the mother. The instinctive behavior pattern of normal, unmedicated neonatal infants during the first hour after birth while in continuous skin‐to‐skin contact with their mothers has been documented elsewhere and includes suckling as the eighth stage 2, 3 in the progression of nine instinctive neonatal behaviors. Breastfeeding within the first hour has been shown to have an inverse relationship with breastfeeding difficulties 4 and neonatal mortality 5.

It is also accepted that maternal medications, including fentanyl, can be transferred from the epidural space to the fetus through placental circulation 6 with a fetal maternal transplacental fentanyl transmission ratio of 0.892 7. A few studies have evaluated the infant outcomes relative to intrapartum analgesics with regard to temperature and crying 8, neonatal hypotonia, increased seizure risk, 1‐minute Apgar scores lower than 7 9, performance on the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale in the first month 10, delayed initiation of breastfeeding 11, onset of lactation 12, breastfeeding duration 13, and supplementation with infant formula 14. A depressive effect on the spontaneous behavior of neonatal infants from maternal pethidine (Demerol) administration before the delivery has been suggested 8.

Several studies have sought to evaluate effects of exposure to epidural medications on infant behaviors and breastfeeding rates in the hours, days, and weeks after birth with conflicting findings. Some studies have found an association between intrapartum epidurals and decreases in neurobehavioral scores 13, 15, rates of suckling within the first hours after birth 8, 11, 14, 16, 17, rates of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge 11, 18, 19, rates of continued breastfeeding at 30 days postpartum 20, 6 weeks postpartum 13, 24 weeks postpartum 21, and increased supplementation with infant formula 18. Other studies have failed to find an association between epidurals and breastfeeding 22, 23. Possible explanations for the conflicting results could be related to differing study designs and lack of control for the compounds and durations of epidural medications 24. One study that looked specifically at the dose of fentanyl found that infants of women who received > 150 micrograms of fentanyl during labor had lower neurobehavioral scores after birth and decreased breastfeeding duration at 6 weeks postpartum 13.

Rates of induction of labor in the United States have been increasing since the early 1990s to 22.8 percent 25, with synthetic oxytocin (synOT) alone trending toward being the most commonly used induction agent 26 in 2012. This is true in spite of synOT receiving a “Black Box” warning (the strongest warning the United States Food and Drug Administration [FDA] can give) stating “Not for Elective Labor Induction: not indicated for elective labor induction since inadequate data to evaluate benefit versus risk; elective induction defined as labor initiation without medical indications” 27. Once it has begun, labor is also often augmented by synOT. Hayes and Weinstein 28 have called for standardization and uniformity of care in the use of oxytocin and report that synOT is “often used in an unstructured manner and without a correct diagnosis of arrested labor” 29.

Not every study has shown negative outcomes on the mother or newborn with the use of synOT. However, administration of synOT has been found to increase the level of lactate in amniotic fluid during labor 30, increase the risk of adverse neonatal outcomes 30, 31, and acidemia of the newborn 32. Other studies connect synOT with delayed initiation of breastfeeding 11, disturbed suckling, and shortened duration of breastfeeding 33, along with multiplying the risk of bottle‐feeding and increasing the risk of discontinuation of breastfeeding at 3 months 34. Neonatal neurobehavioral prefeeding cues and organization 35 have also been negatively affected by synOT. An increase in regional anesthesia, instrumental delivery, and cesarean section 31 has been associated with the use of synOT in some studies, although a systematic review did not find this result and called for more research 36. Possible links have been suggested between synOT and subsequent childhood Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) onset 37 and Autism Spectrum Disorders 38.

Early skin‐to‐skin contact between mother and infant shortly after birth has been recognized since the 1970s as having both short‐term and long‐term effects on breastfeeding and the mother infant relationship 1, 39, 40, 41, as well as on maternal self‐efficacy 42. Full‐term newborns are more stable when skin‐to‐skin with their mothers and have fewer distress vocalizations 43. The uncompromised newborn will demonstrate instinctive behaviors when placed skin‐to‐skin on mother's chest immediately after birth and, if undisturbed, will find the nipple by itself and begin to suckle during the first hour after birth 2, 3. These instinctive behaviors have been categorized into nine progressive stages (Fig. 1). When skin‐to‐skin with their mothers, uncompromised term newborns go through these stages, unassisted, at varying rates and usually achieve suckling within 60–90 minutes after birth. These stages offer an opportunity to observe the newborn's complex, instinctive behaviors in a systematic manner. The newborn must coordinate autonomic, sensory, motor, and behavioral state systems to progress smoothly through the 9 Stages within the first hour after birth. Research has shown that attenuated neonatal neurobehavioral organization (NNBO), when measured soon after birth, could be related to the slow initiation of optimal sucking behavior 44.

Figure 1.

Widström's 9 instinctive stages of neonatal behavior during skin‐to‐skin contact immediately after birth (3).

Our hypothesis was that intrapartum medications would have an effect on the ability of neonatal infants to suckle during the first hour after birth while in skin‐to‐skin contact with their mothers. Specifically, we hypothesized that increased doses of narcotic medications would result in lower rates of suckling in the first hour after birth. The effects of other commonly used labor medications were unknown and would be determined by study analysis.

Methods

Sample and Setting

The study was conducted at Loma Linda University Medical Center (LLUMC), a large teaching hospital in the Western part of the United States that has approximately 2,500 births per year. The staff previously had received in‐services and training in the provision of skin‐to‐skin care using the PRECESS method 45, 46, 47. The hospital routinely provides uninterrupted skin‐to‐skin contact for all healthy newborns immediately after all vaginal births for at least 1 hour. The hospital practice includes a consistent formulary for medications used in epidurals, including fentanyl. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of LLUMC.

Informed consent was obtained from clinically uncomplicated primipara and multipara mothers who were approached on arrival to the labor and delivery ward over the course of 4 weeks in 2013: 1 week each in May, July, August, and December. Informed consent materials were available in English and Spanish. A translator was available for Spanish‐speaking participants. The study's inclusion criteria included women who were ≥ 18 years of age, healthy, English or Spanish speaking as their primary language, 37–42 weeks pregnant, and who had planned a vaginal birth. Infants were eligible if they were full‐term gestation, healthy, and had no known abnormalities. Names and identifying information were removed from the medical records and given a linked code. This unique code was also recorded on the video of the baby during the first hour after birth.

The study participants self‐selected to labor without any pain medication or to labor with epidural anesthesia. The study did not change any hospital protocols or routines, with the exception of the addition of the video recording of the baby for the first hour after birth while skin‐to‐skin with the mother.

Data Collection Procedures

After the birth, the full‐term newborn was to be placed ventrally on the mother's bare chest in a semireclined position, dried and covered with a warm blanket. The baby was to be kept skin‐to‐skin with the mother for at least the first hour after birth unless there was a medical reason to stop the process. The baby was allowed to move through Widström's Stages, unassisted. The video researchers were positioned behind the mother's head and video recorded the neonatal activities for the first hour after birth. If the baby was removed for examination by the nurse or by Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) staff for < 10 minutes and returned to the mother, the mother and baby remained in the study. The protocol included the provision that if the baby was removed by the family, nurse or by NICU staff for > 10 minutes, the mother and baby dyad was removed from the study, and the video recording stopped. The dyad was then included as one of the dyads removed during labor or postpartum for medical reasons.

Demographics and medications received during labor were collected from the Electronic Medical Record System after the completion of each video recording or after a consented mother and baby were removed from the study group for medical reasons.

The anesthesiologist determined, administered, and recorded each participant's epidural drug dosage using the standard hospital protocols. The drug concentration of the standardized epidural infusion was 375 mg ropivacaine (Naropin) and 500 mcg fentanyl (Sublimaze) in preservative‐free sodium chloride 0.9 percent in a 250 mL bag. The epidural catheter placement test dose included 3–5 mL of 1.5 percent lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine. Following a negative test dose, the participant was given a bolus of 100 mcg of fentanyl via the epidural catheter. The single exception was one mother who received an initial bolus of 25 mcg of fentanyl. A loading dose of 2 mg/mL (0.2%) ropivicaine was adjusted to the participant's height. An average dose of 5–8 mL of 0.2 percent ropivicaine was given. The typical rate of the epidural infusion was 8 mL/hour, although women could add an additional bolus dose of 4 mL every 15 minutes if they were uncomfortable. In the case of continued inadequate pain control, women could receive an additional bolus of local anesthetic (usually 0.2% ropivicaine) from the anesthesiologist. The total dosage of all medications given to each participant was obtained from the participant's medical record.

The LLUMC Oxytocin Protocol, effective May 2012, dictates there be “physicians orders before receiving oxytocin infusion, two RNs at the bedside to verify dose, route and time, and an increase of 1 milli‐unit/minute every 30 minutes until adequate uterine activity is achieved, to a maximum dose of 24 milli‐units/minute of oxytocin.” A physician's orders may modify the specific process per mother.

The study protocol was approved by the LLUMC Institutional Review Board. All women gave informed consent for themselves and their babies to participate.

Video Analysis

Infants were video recorded during the first hour after birth. Two research assistants were trained to recognize Widström's 9 Stages of neonatal behavior by viewing a professional video 48 that defined and illustrated each stage and then attending a workshop about Widström's 9 Stages. The research assistants, who were blinded to mother's medications, used MAXQDA 11.0.2 (VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany), a professional qualitative data analysis software, to separately and independently code all video recordings for the 9 Stages. This paper reports only on the achievement of the baby regarding Stage 8, suckling. Suckling is defined as the baby self attaching to the nipple and beginning to breastfeed, as part of a continuum of behaviors during the first hour.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the Adapted Kaplan–Meier, ANOVA, t‐tests, Binary Logistic Regression, and Binary Logistic Multiple Regression. We examined the relationship between the recorded administered amounts of synOT and fentanyl (via epidural), duration of epidural, the birthweight, five‐minute Apgar scores, and whether or not the baby suckled in the first hour as determined by video analysis. A 95 percent confidence level was used to test statistical significance, with p < 0.05 being a significant result. Ninety‐five percent confidence intervals for odds ratios were considered statistically significant. For the purposes of analysis, we looked at the mothers who had received no synOT and no fentanyl, mothers who received fentanyl without synOT, mothers who received synOT without fentanyl, and mothers who received both fentanyl and synOT.

Results

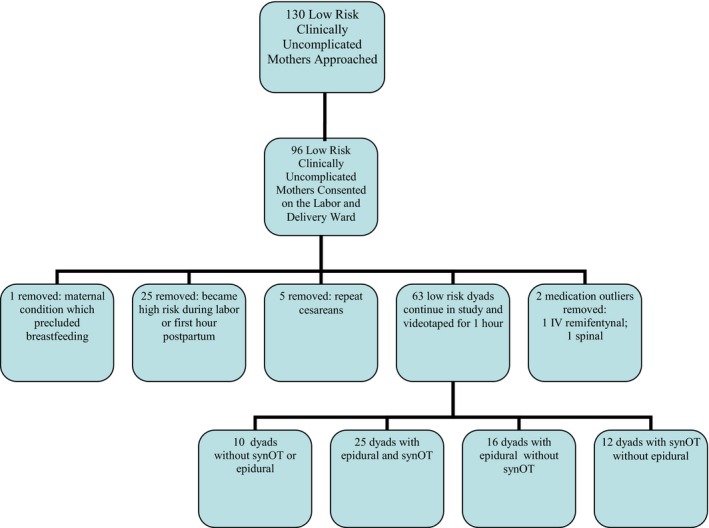

Our data are reported as collected on 63 low‐risk mother–infant dyads (10 no synOT and no fentanyl, 25 both fentanyl and synOT, 16 fentanyl without synOT, 12 synOT without fentanyl) (Fig. 2). Cross‐tabulation showed no significant differences in age (p = 0.541), number of pregnancies (p = 0.157) or number of births (p = 0.508) between the four groups (Table 1). There were no differences between the four groups in relation to birthweight (p = 0.112), gestational age (p = 0.458), 1‐minute Apgar score (p = 0.638), or 5‐minute Apgar score (p = 0.651) (Table 1). There was no difference in suckling between babies that were removed for < 10 minutes or stayed in continuous skin to skin (p = 0.533).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of consented mothers, collected over 4 weeks in May, July, August, and December at LLUMC, 2012, resulting in 63 mothers who were included in the study analysis.

Table 1.

Consented Dyad Demographic Data, Grouped by Common Labor Medications, LLUMC, 2012

| Characteristics (mean) | No synOT, no fentanyl, n = 10 | Fentanyl without synOT, n = 25 | SynOT without fentanyl, n = 16 | Fentanyl with synOT, n = 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | ||||

| Age (years) | 28.3 | 26.4 | 28.7 | 29.2 |

| Number of pregnancies | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| Number of births | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Infant | ||||

| 1‐minute Apgar score | 7.8 | 8.2 | 8.0 | 8.1 |

| 5‐minute Apgar score | 9.1 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 8.9 |

| Gestational age | 39.2 | 39.6 | 39.9 | 39.4 |

| Birthweight (g) | 3,260.1 | 3,517.5 | 3,344.8 | 3,201.4 |

synOT = synthetic oxytocin; LLUMC = Loma Linda University Medical Center.

The levels of synOT and fentanyl were compared among the different groups. The mean amount of synOT in mothers who received synOT but no fentanyl (3,937.92 mcg) was not significantly different in mothers who received both synOT and fentanyl (5,704.40 mcg) (p = 0.416). The mean amount of fentanyl in mothers who received fentanyl without synOT (169.64 mcg) was significantly lower in mothers who received fentanyl with synOT (264.45 mcg). There is a correlation between the mothers who received fentanyl and those who received synOT (Pearson Correlation of .402, p = 0.001). There was also a correlation between the amount of fentanyl and the duration of epidural anesthesia (Pearson Correlation of 0.936, p = 0.001).

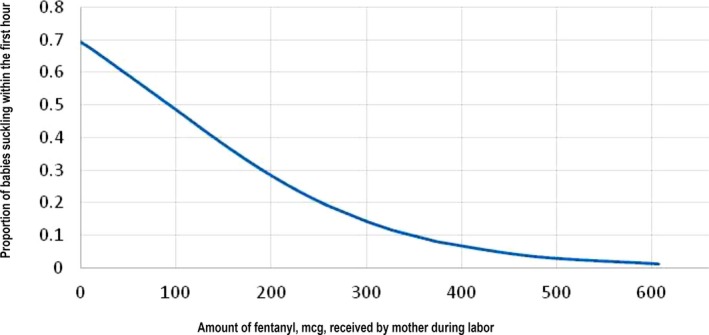

A logistic regression was used to determine the likelihood of a baby suckling during the first hour after birth while skin‐to‐skin with the mother in relation to the amount of fentanyl a mother received during labor. Figure 3 shows a dose‐dependent inverse relationship between the likelihood of achieving suckling within the first hour after birth and the increased amounts of exposure to fentanyl (p = 0.001, R2 = 0.264, constant significant at 0.05, CI 0.987, 0.997).

Figure 3.

Logistic regression of the proportion of babies of consented mothers who achieved Widström's Stage 8, suckling, by amount of fentanyl mother received during labor at LLUMC, 2012 (p = 0.01).

To study possible effects of maternal epidural analgesia and synOT augmentations on infant inborn suckling behavior, we conducted a binary logistic regression analysis with suckling or not suckling as the dependent variable. The independent variables were: amount of fentanyl (mcg), synOT (milli‐units) given to the mother, infant birthweight and 5‐minute Apgar score.

The following three independent variables were found to be significant predictors for whether the infant suckled or not: amount of Fentanyl (p = 0.01), amount of synOT (p = 0.026), and the Apgar score at 5 min (p = 0.046) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Results of Consented Mothers by Amount of Fentanyl, Amount of Pitocin, and 5‐minute Apgar Score as Compared to Infant Suckling Within the First Hour After Birth, LLUMC, 2012

| B | SE | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fentanyl Epi | −0.009 | 0.004 | 6.666 | 1 | 0.010 | 0.991 |

| Pitocin | 0.000 | 0.000 | 4.959 | 1 | 0.026 | 1.000 |

| 5‐minute Apgar score | −1.955 | 0.982 | 3.965 | 1 | 0.046 | 0.142 |

| Constant | 19.121 | 9.059 | 4.455 | 1 | 0.035 | 201,532,307.369 |

synOT = synthetic oxytocin; LLUMC = Loma Linda University Medical Center.

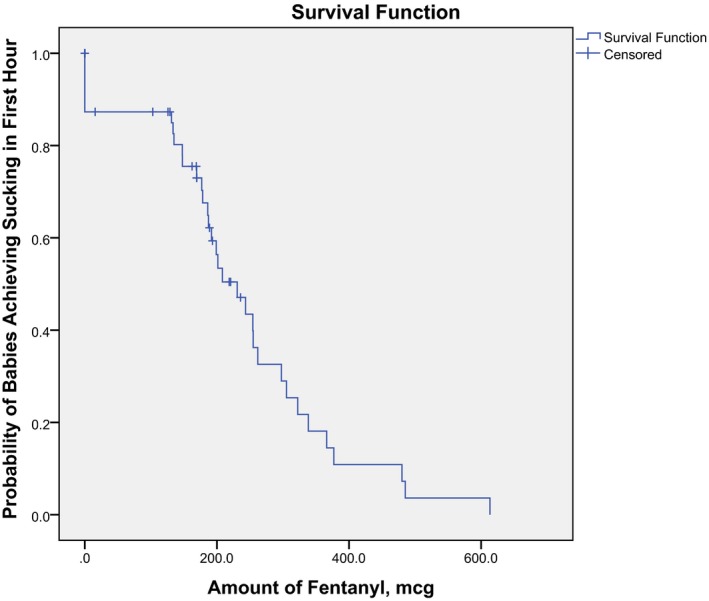

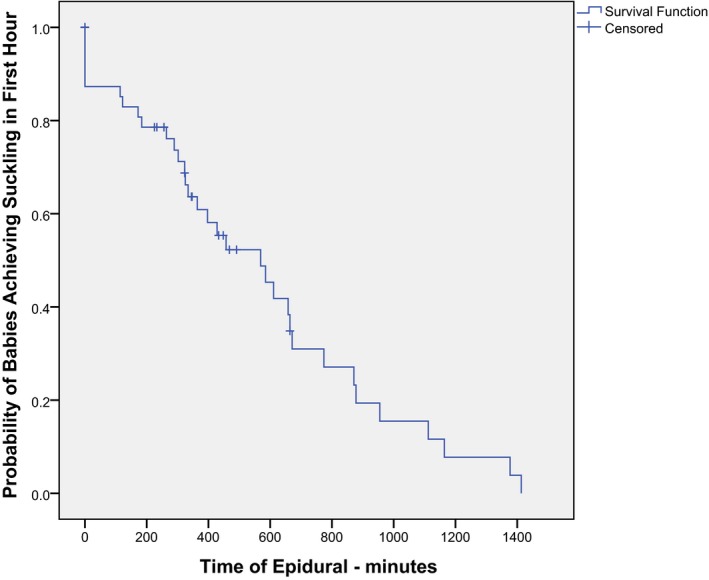

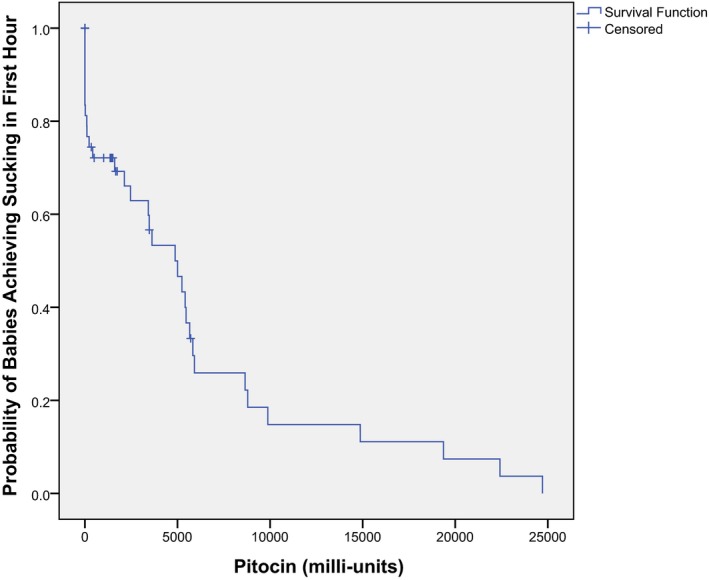

Since some mothers had fentanyl administered as well as synOT, we analyzed them separately and together taking into account a possible interaction. To illustrate the separate effects of fentanyl and synOT on the proportion of infants who suckled, two separate Kaplan–Meier curves were made (Figs 4, 5, 6). Every mother who received an epidural received a 100 mcg bolus of fentanyl, with only one exception, resulting in only one data point between 0 and 100 mcg.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curve for comparing the amount of fentanyl to the progression to suckling by the baby during the first hour, LLUMC, 2012. Note: The majority of these dyads also had exposure to synOT.

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier curve for comparing the duration of the epidural to the progression to suckling by the baby during the first hour, LLUMC, 2012. Note: The majority of these dyads also had exposure to synOT.

Figure 6.

Kaplan–Meier curve comparing the amount of synOT to the progression of suckling by the baby during the first hour, LLUMC, 2012. Note: The majority of these dyads also had exposure to fentanyl.

Discussion

As shown in both the figure of the logistical regression (Fig. 3) and the Kaplan–Meier curve (Fig. 4), the proportion of infants suckling in the present study is related to the amount of fentanyl in a stepwise decreasing pattern. In Fig. 4, the stepwise decrease in proportion of infant suckling within the first hour begins at about 150 mcg of fentanyl. This correlates with the amount of fentanyl that Bielin and colleagues' research 13 suggested as disturbing to breastfeeding. They found that babies whose mother's received > 150 mcg of fentanyl (with a maximum of 395 mcg) in their epidural were less likely to be breastfeeding at 6 weeks.

Research by Wilson and colleagues did not find that fentanyl significantly affects breastfeeding initiation 49. However, the mean dose of fentanyl in their study was 107.3 mcg in the combined spinal epidural group, and 162.8 mcg in the low‐dose infusion. Jordan et al presented a dose–response association correlating the amount of fentanyl to formula feeding, showing that fentanyl‐based epidurals (with a mean dose of 129 mcg–low dose), do not significantly affect breastfeeding initiation 19, 49. In the present study, mothers who received fentanyl without synOT had an average amount of fentanyl of 169.65 mcg (max 243.3 mcg, min 102.9 mcg). Mothers who received both fentanyl and synOT had an average amount of fentanyl of 264.45 mcg (max 613.4 mcg, min 15.7 mcg). These mean rates are higher than other mean values published.

In the binary logistic multiple regression model, we found that the variables fentanyl, synOT, and Apgar score were all significantly related to whether the infant suckled or not. The added effect of these variables on the dependent variable suckling or not is described by a Kaplan–Meier curve in terms of proportions of infants suckling in relation to either the amount of epidural analgesia (Fig. 4), the duration of the epidural analgesia in minutes (Fig. 5), or the amount of synOT (Fig. 6). It should thus be noted that this Kaplan–Meier curve in practice represents the effect of the amount of two drugs: fentanyl and synOT on the infant's capability to suckle or not within the first hour.

We recognize that because many mothers in our study had both fentanyl and synOT, there may be a complex relationship between these two commonly used obstetric drugs. Other studies have also recognized this complexity 20, 50, 51. An unanswered question is the role of synOT in conjunction with fentanyl. It is well known that synOT leads to stronger contractions that are associated with higher pain levels. The higher doses of fentanyl in mothers who also received synOT suggest the need for higher doses of analgesics. Wiberg‐Itzel and colleagues 30 correlated the administration of synOT with the level of lactate in the mother's amniotic fluid and also with the frequency of adverse neonatal outcome. Researchers Berglund et al and Jonsson et al correlate the overuse of synOT with the risk of lowered Apgar score at 5 minutes 32, 52. The use of synOT has also been found to increase the risk of bottle‐feeding and weaning from the breast by 3 months 34. Fernández et al analyzed films of 2‐day‐old newborns being tested for Primitive Neonatal Reflexes, including suckling 33. They described a negative association between the intrapartum synOT dose and suckling and postulate that synOT administered to the mother during labor could cross the placenta and the baby's blood‐brain barrier. In addition to effects on the baby from increased amniotic lactate and acidosis cited above, Jonas and colleagues 50 found that intrapartum synOT effected the amount of oxytocin the mother produced while breastfeeding on the second day after birth; the mothers who had been given the highest doses of synOT had the least endogenous oxytocin on day 2, possibly because of a loss of myometrial oxytocin receptors 51. Although a measurement of lactate in amniotic fluid was not done in our study, other studies suggest that the newborn's behavior could be an indirect effect of increased lactate in the amniotic fluid as a result of increased synOT 30, 32.

Limitations of this study might include the sample size, although the Wald test demonstrated significance. In addition, 25 consented mothers were removed from the study because they became high risk during the peripartum or immediate postpartum period. Future research should investigate why > 25 percent of the consented, low‐risk mothers moved into the medically high‐risk category.

Strengths of this study include our attempts to minimize the complexities of hospital practice, Baby‐Friendly Hospital status, maternal self‐efficacy, and social support by studying the innate behaviors of the newborn while undisturbed in skin‐to‐skin contact with its mother within the first hour after birth, as well as examining the effects of intrapartum medications individually and together. Further research is warranted to explore the reliability of these findings in other settings, with other modalities of medication delivery and with cesarean births.

Conclusions

Intrapartum exposure to high doses of the drugs fentanyl and synOT significantly decreased the likelihood of the baby suckling while skin‐to‐skin during the first hour after birth. The combined effects of synOT and fentanyl need further exploration. Knowledge of this association should be taken into account when considering risks and benefits of administering these medications during the course of labor management. Mothers who desire to breastfeed their babies should also evaluate this risk when considering the use of these medications.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors confirm that they have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence their work.

Acknowledgments

We thank the delightful mothers and babies who so graciously participated in this study, as well as the hardworking and dedicated nurses and doctors. We thank the research assistants, Judy Blatchford, Natasha Mishchenko, Aisha Stewart, Cynthia Mach, and Allysa Erskine. Thank you to Jocelyn Pitman, Glenn Bush and Ann‐Sofie Mattiesen for their statistical expertise. Funding for this project was provided by Loma Linda University Medical Center and Healthy Children Project, Inc.

(Birth 42:4 December 2015)

References

- 1. Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N, Dowswell T. Early skin‐to‐skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD003519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Widström AM, Wahlberg V, Matthiesen AS, et al. Short‐term effects of early suckling and touch of the nipple on maternal behaviour. Early Hum Dev 1990;21(3):153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Widström A‐M, Lilja G, Aaltomaa‐Michalias P, et al. Newborn behaviour to locate the breast when skin‐to‐skin: A possible method for enabling early self‐regulation. Acta Paediatr 2011;100(1):79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carberry AE, Raynes‐Greenow CH, Turner RM, Jeffery HE. Breastfeeding within the first hour compared to more than one hour reduces risk of early‐onset feeding problems in term neonates: A cross‐sectional study. Breastfeed Med 2013;8(6):513–514. Epub 2013 Jun 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edmond KM, Zandoh C, Quigley MA, et al. Delayed breastfeeding initiation increases risk of neonatal mortality. Pediatrics 2006;117(3):e380–e386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cooper J, Jauniaux E, Gulbis B, et al. Placental transfer of fentanyl in early human pregnancy and its detection in fetal brain. Br J Anaesth 1999;82(6):929–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moisés EC, deBarros Duarte L , de Carvalho Cavalli R, et al. Pharmacokinetics and transplacental distribution of fentanyl in epidural anesthesia for normal pregnant women. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(7):517–522. Epub 2005 Jul 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ransjö‐Arvidson AB, Matthiesen AS, Lilja G, et al. Maternal analgesia during labor disturbs newborn behavior: Effects on breastfeeding, temperature, and crying. Birth. 2001;28(1):5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lieberman E, Lang J, Richardson DK, et al. Intrapartum maternal fever and neonatal outcome. Pediatrics 2000;105(1 Pt 1):8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sepkoski CM, Lester BM, Ostheimer GW, Brazelton TB. The effects of maternal epidural anesthesia on neonatal behavior during the first month. Dev Med Child Neurol 1992;34(12):1072–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wiklund I, Norman M, Uvnäs‐Moberg K, et al. Epidural analgesia: Breast‐feeding success and related factors. Midwifery 2009;25(2):e31–e38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lind JN, Perrine CG, Li R. Relationship between use of labor pain medications and delayed onset of lactation. J Hum Lact 2014;22:167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beilin Y, Bodian CA, Weiser J, et al. Effect of labor epidural analgesia with and without fentanyl on infant breast‐feeding: A prospective, randomized, double‐blind study. Anesthesiology 2005;103(6):1211–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baumgarder DJ, Muehl P, Fischer M, Pribbenow B. Effect of labor epidural anesthesia on breast‐feeding of healthy full‐term newborns delivered vaginally. J Am Board Fam Pract 2003;16(1):7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Loftus JR, Hill H, Cohen SE. Placental transfer and neonatal effects of epidural sufentanil and fentanyl administered with bupivacaine during labor. Anesthesiology 1995;83(2):300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nissen E, Lilja G, Matthiesen AS, et al. Effects of maternal pethidine on infants' developing breast feeding behaviour. Acta Paediatr 1995;84(2):140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Riordan J, Gross A, Angeron J, et al. The effect of labor pain relief medication on neonatal suckling and breastfeeding duration. J Hum Lact 2000;16(1):7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Volmanen P, Valanne J, Alahuhta S. Breast‐feeding problems after epidural analgesia for labour: A retrospective cohort study of pain, obstetrical procedures and breast‐feeding practices. Int J Obstet Anesth 2004;13(1):25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jordan S, Emery S, Bradshaw C, et al. The impact of intrapartum analgesia on infant feeding. BJOG 2005;112(7):927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dozier AM, Howard CR, Brownell EA, et al. Labor epidural anesthesia, obstetric factors and breastfeeding cessation. Matern Child Health J 2013;17(4):689–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Torvaldsen S, Roberts CL, Simpson JM, et al. Intrapartum epidural analgesia and breastfeeding: A prospective cohort study. Int Breastfeed J 2006;1:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nystedt A, Edvardsson D, Willman A. Epidural analgesia for pain relief in labour and childbirth ‐ a review with a systematic approach. J Clin Nurs 2004;13(4):455–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Halpern SH, Levine T, Wilson DB, et al. Effect of labor analgesia on breastfeeding success. Birth 1999;26(2):83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Szabo AL. Intrapartum Neuraxial Analgesia and Breastfeeding Outcomes: Limitations of Current Knowledge. Anesth Analg 2013;116:399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Michelle JK, Osterman, MJ . Births: Final Data for 2012. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2013;62(9):1–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mealing NM, Roberts CL, Ford JB, et al. Trends in induction of labour, 1998‐2007: A population‐based study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49(6):599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Black Box Drug Look‐Up. Accessed May 13, 2014. Available at: https://online.epocrates.com/u/10b2236/oxytocin/Black+Box+Warnings.

- 28. Hayes EJ, Weinstein L. Improving patient safety and uniformity of care by a standardized regimen for the use of oxytocin. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(6):622.e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.01.039. Epub 2008 Mar 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Selin L, Almström E, Wallin G, Berg M. Use and abuse of oxytocin for augmentation of labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2009;88(12):1352–1357. doi:10.3109/00016340903358812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wiberg‐Itzel E, Pembe AB, Wray S, et al. Level of lactate in amniotic fluid and its relation to the use of oxytocin and adverse neonatal outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014;93:80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buchanan SL, Patterson JA, Roberts CL, et al. Trends and morbidity associated with oxytocin use in labour in nulliparas at term. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2012;52(2):173–178. doi:10.1111/j.1479‐828X.2011.01403.x. Epub 2012 Mar 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jonsson M, Nord_en‐Lindeberg S, Ostlund I, Hanson U. Acidemia at birth, related to obstetric characteristics and to oxytocin use, during the last two hours of labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87:745–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fernández IO, Gabriel MM, Martinez AM, et al. Newborn feeding behaviour depressed by intrapartum oxytocin: A pilot study. Acta Paediatr 2012;101:749–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Garcia‐Fortea P, González‐Mesa E, Blasco M, et al. J Oxytocin administered during labor and breast‐feeding: A retrospective cohort study. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27(15):1598–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bell AF, White‐Traut R, Rankin K. Fetal exposure to synthetic oxytocin and the relationship with prefeeding cues within one hour postbirth. Early Hum Dev 2013;89(3):137–143. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2012.09.017. Epub 2012 Oct 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Costley PL, East CE. Oxytocin augmentation of labour in women with epidural analgesia for reducing operative deliveries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD009241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kurth L, Haussmann R. Perinatal Pitocin as an early ADHD biomarker: Neurodevelopmental risk? J Atten Disord 2011;15(5):423–431. doi:10.1177/1087054710397800. Epub 2011 Apr 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Emberti Gialloreti L, Benvenuto A, Benassi F, Curatolo P. Are caesarean sections, induced labor and oxytocin regulation linked to Autism Spectrum Disorders? Med Hypotheses. 2014;82(6):713–718. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2014.03.011. Epub 2014 Mar 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. De Chateau P, Wiberg B. Long‐term effect on mother‐infant behaviour of extra contact during the first hour post partum. II. A follow‐up at three months. Acta Paediatr Scand 1977;66(2):145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Righard L, Alade MO. Sucking technique and its effect on success of breastfeeding. Birth 1992;19(4):185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mahmood I, Jamal M, Khan N. Effect of mother‐infant early skin‐to‐skin contact on breastfeeding status: A randomized controlled trial. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2011;21(10):601–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aghdas K, Talat K, Sepideh B. Effect of immediate and continuous mother‐infant skin‐to‐skin contact on breastfeeding self‐efficacy of primiparous women: A randomised control trial. Women Birth 2014;27(1):37–40. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2013.09.004. Epub 2013 Nov 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Christensson K, Cabrera T, Christensson E, et al. Separation distress call in the human neonate in the absence of maternal body contact. Acta Paediatr 1995;84(5):468–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Radzyminski S. Neurobehavioral functioning and breastfeeding behavior in the newborn. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2005;34(3):335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cadwell K, Widström AM, Brimdyr K, et al. A comparison of three interventions to achieve continuous uninterrupted skin‐to‐skin care until the completion of the first breastfeed as the standard of care. (abstract). Breastfeeding Med 2009;4(4):240. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Crenshaw JT, Cadwell K, Brimdyr K, et al. Use of a video‐ethnographic intervention (PRECESS Immersion Method) to improve skin‐to‐skin care and breastfeeding rates. Breastfeed Med 2012;7(2):69–78. Epub 2012 Feb 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brimdyr K, Widström A‐M, Cadwell K, et al. A realistic evaluation of two training programs on implementing skin‐to‐skin as a standard of care. J Perinat Educ 2012;21(3):149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brimdyr K, Widström A‐M, Svensson K (2011). Skin‐to‐Skin in the First Hour After Birth: Practical Advice for Staff After Vaginal and Cesarean Birth. [DVD], Sandwich, MA: Healthy Children Project Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wilson MJA, MacArthur C, Cooper GM, et al. Epidural analgesia and breastfeeding: A randomised controlled trial of epidural techniques with and without fentanyl and a non‐epidural comparison group. Anaesthesia 2010;65(2):145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jonas K, Johansson LM, Nissen E, et al. Effects of intrapartum oxytocin administration and epidural analgesis on the concentration of plasma oxytocin in response to suckling during the second day postpartum. Breastfeeding Med. 2009;4:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Phaneuf S, Rodríguez Liñares B, TambyRaja RL, et al. J Loss of myometrial oxytocin receptors during oxytocin‐induced and oxytocin‐augmented labour. Reprod Fertil. 2000;120(1):91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Berglund S, Norman M, Grunewald C, et al. Neonatal resuscitation after severe asphyxia–a critical evaluation of 177 Swedish cases. Acta Paediatr 2008;97:714–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]