Abstract

Numerous studies have attempted to identify early physiological abnormalities in infants and toddlers who later develop autism spectrum disorder (ASD). One potential measure of early neurophysiology is the auditory brainstem response (ABR), which has been reported to exhibit prolonged latencies in children with ASD. We examined whether prolonged ABR latencies appear in infancy, before the onset of ASD symptoms, and irrespective of hearing thresholds. To determine how early in development these differences appear, we retrospectively examined clinical ABR recordings of infants who were later diagnosed with ASD. Of the 118 children in the participant pool, 48 were excluded due to elevated ABR thresholds, genetic aberrations, or old testing age, leaving a sample of 70 children: 30 of which were tested at 0–3 months, and 40 were tested at toddlerhood (1.5–3.5 years). In the infant group, the ABR wave‐V was significantly prolonged in those who later developed ASD as compared with case‐matched controls (n = 30). Classification of infants who later developed ASD and case‐matched controls using this measure enabled accurate identification of ASD infants with 80% specificity and 70% sensitivity. In the group of toddlers with ASD, absolute and interpeak latencies were prolonged compared to clinical norms. Findings indicate that ABR latencies are significantly prolonged in infants who are later diagnosed with ASD irrespective of their hearing thresholds; suggesting that abnormal responses might be detected soon after birth. Further research is needed to determine if ABR might be a valid marker for ASD risk. Autism Res 2016, 9: 689–695. © 2015 The Authors Autism Research published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on behalf of International Society for Autism Research

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, auditory brainstem response, hearing

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disorder that is typically diagnosed between 2 and 4 years of age [American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Volkmar et al., 2014]. Early diagnosis of ASD may allow for implementation of early interventions [Dawson et al., 2010]. Auditory brainstem responses (ABR) have been used to study auditory function of children with ASD [Rosenhall, Nordin, Brantberg, & Gillberg, 2003; Roth, Muchnik, Shabtai, Hildesheimer, & Henkin, 2012], and to date, several studies have reported that children with ASD exhibit prolonged ABR latencies in comparison to controls [Dabbous, 2012; Fujikawa‐Brooks, Isenberg, Osann, Spence, & Gage, 2010; Kwon, Kim, Choe, Ko, & Park, 2007; Maziade et al., 2000; Rosenhall et al., 2003; Russo, Hornickel, Nicol, Zecker, & Kraus, 2010; Tas et al., 2007; Thivierge, Bédard, Côté, & Maziade, 1990; Wong & Wong, 1991], while others have found no such relationship [Courchesne, Courchesne, Hicks, & Lincoln, 1985; Tharpe et al., 2006]. These discrepancies may be due to differences in the inclusion and exclusion criteria set for each study. Recently, prolonged ABR latencies were reported in children at age 2–4 years with normal hearing who were undergoing clinical evaluation for ASD [Roth et al., 2012], suggesting that ABR latencies are prolonged at the age in which ASD symptoms become apparent. It is not known, however, whether such prolongation may be apparent even before the onset of ASD symptoms, and thus may serve as a potential early measure for ASD risk.

Research with preterm infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) has shown that transient prolonged neonatal ABR latencies are associated with behavioral markers of socio‐communicative deficits including, social gaze disengagement [Geva et al., 2011; Karmel, Gardner, Zappulla, Magnano, & Brown, 1988], repetitive behaviors [Cohen et al., 2013], and behavioral inhibition [Geva, Schreiber, Segal‐Caspi, & Markus‐Shiffman, 2013]. It is important to note that neonatal complications and prematurity are significant risk factors for ASD, especially in infants born before 33 weeks gestation age [Johnson et al., 2010; Karmel et al., 2010; Schendel & Bhasin, 2008; Volkmar et al., 2014]. These neonatal findings suggest that prolonged ABRs during the neonatal period may be common in infants who later develop ASD.

ABR testing is routinely used as a clinical tool for assessing the functional integrity of the auditory system and for measuring hearing thresholds in infants with a risk for developmental abnormalities, including, but not limited to, hearing impairments [World‐Health‐Organization, 2010]. To determine whether abnormal ABR is already apparent in infancy for children with ASD, we performed a retrospective study comparing the ABR of infants with normal hearing thresholds who were later diagnosed with ASD, with case‐matched control infants.

Patients and Methods

Participants

ASD groups

We examined patient files of all children born between 1997 and 2013 who were later diagnosed with ASD according to DSM‐IV criteria [American Psychiatric Association, 2000] at the Weinberg Child Development Center, Sheba Medical Center, Israel. Of these files (n = 898), 118 children had records of ABR exams, which were conducted at the Hearing, Speech, and Language Center at Sheba Medical Center. Of the 118 children in the participant pool, 48 were excluded due to elevated ABR thresholds (N = 35), genetic aberrations (N = 6), or old testing age (N = 7), leaving a sample of 70 children who were later diagnosed with ASD.

The final analysis was conducted on a total of 30 infants and 40 toddlers later diagnosed with ASD. Infants were referred for an ABR evaluation due to one or more of the following risk factors for hearing impairment [Joint‐Committee‐on‐Infant‐Hearing, 2007]: prolonged stay in the NICU [prematurity (n=19), born at term (n=5)], familial history of hearing impairment (n=3), ear skin tag (n = 1), autotoxic medication (e.g., aminoglycoside) and seizures (n=1), or failure on newborn hearing screening test (n=1). Participants were tested at a chronological age of 0.2–6.5 months (Mean 3.07 ± 1.27 months), which after correction for prematurity was between term age and 3.2 months (Mean 1.61 ±.82 months; Table 1). An additional group of 40 toddlers were tested between 1.5 and 3.5 years of age (Mean 2.38 ± 0.50 years). These participants were referred for an ABR evaluation as part of their ASD diagnostic evaluation to rule out a hearing impairment due to their inability to perform a behavioral audiometry. Both ASD groups had 20% females.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of MEAN (SD) of ASD and Case‐Matched Controls

| ASD (n = 30) | Case‐matched Controls (n = 30) | F‐Test | Sig. (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test age (months) | 3.07 (1.27) | 3.16 (0.96) | 0.097 | 0.756 |

| Birth week (weeks) | 33.67 (5.53) | 33.90 (5.15) | 0.029 | 0.866 |

| Corrected test age (months) | 1.61 (0.82) | 1.76 (0.76) | 0.498 | 0.483 |

| Gender (%Females) | 20 | 20 | 0a | 1.000 |

ϰ2.

Infant control group

Infants with ASD were compared to a case‐matched control group (n = 30), in which a control case was matched with each ASD case on birth week, gender, and chronological age corrected for prematurity. Participants were all born at the Sheba Medical Center and referred for an ABR evaluation for one of the following reasons: prematurity, including a prolonged stay in the NICU (n = 20), or familial history of hearing impairment and other risk factors (n = 10). Case‐matched control infants had normal ABR air‐conduction thresholds to clicks and 1 kHz tone bursts stimuli. They were all tested between 2.0 and 5.5 months of chronological age (Mean 3.16 ± 0.96), which after correction for prematurity was between 0.5 and 3.4 months (Mean 1.76 ± 0.76). Birth week and infant age during the exam did not differ significantly between the case‐matched control and ASD group [Birth week: ASD Mean 33.67 ± 5.53 weeks; Case‐matched controls Mean 33.90 ± 5.15 weeks. Birth week: (F(1,58) = 0.029; P = 0.866); Corrected age: (F(1,58) = 0.498; P = 0.483)]. Both ASD and case‐matched control groups included 6 female participants and 24 male participants (20% female). All control participants had no ASD diagnosis according to Sheba Medical Center's records, though it cannot be ruled out with complete certainty that no diagnosis was made elsewhere.

Toddlers control data

The toddler group was compared to clinical norms (n = 75) [Roth et al., 2012]. It was not possible to use control toddlers because in clinical audiological practice ABRs are rarely recorded in healthy, typically developing children at 2 years of age and older, as hearing thresholds are reliably obtained by means of behavioral audiometry at these ages. Moreover, ABR recordings in toddlers are performed under sedation or anesthesia, hence, collecting data from healthy toddlers is limited and raises ethical concerns. Based on the findings that the ABR matures rapidly and reaches a plateau by 12–18 months of age [Hecox & Galambos, 1974], clinical norms were used based on ABR data from 75 normal‐hearing young adults for click stimuli [Roth et al., 2012].

ABR Measurements

All ABR recordings were performed using the Biologic Navigator‐Pro Evoked Potential System (Natus Medical Inc., Mundelein, IL, USA) employing the same protocol at the same site. Electrodes were placed on the high forehead (Fz), the ipsilateral earlobe, and the contralateral earlobe as ground. Responses were amplified with a gain of 100,000 and digitally filtered with a bandwidth of 100–3000 Hz. Each ear was stimulated separately by alternating click at 85 dB normal hearing level (nHL), with a presentation rate of 39.1/second that were delivered using Etymotic Research ER‐3 insert earphones. Two separate recordings that included 2000 individual sweeps were averaged. For both the study and control groups, ABR recordings were performed by certified audiologists. Testing was performed during natural sleep in infants under 3 months of age and under chloral hydrate sedation for older infants.

Data Analysis

Absolute latencies of waves I, III, and V as well as Inter‐Peak Latencies (IPL) I–III, III–V, and I–V were identified manually and compared across infant groups using Multivariate Analysis of Co‐Variance (MANCOVA), in which age was used as a covariate since ABR absolute latencies and IPLs decrease with age in the first months of life. ABR recordings in response to right or left ear stimulations were assessed separately. Absolute latencies and IPLs were compared between the toddler ASD group and age appropriate clinical norms using a one‐sample T‐test. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistics (version 22).

In an additional analysis, we used a classification algorithm and a leave‐on‐out validation scheme to determine how accurately one could separate ASD and control infants based on the latency of the fifth ABR wave. Classification included a receiver‐operating characteristic analysis where the optimal criterion/threshold (i.e., latency value) for separating the two groups was computed. Classification accuracy was then tested by determining whether the group identity of the left‐out subject was accurately decoded using the computed threshold across groups (i.e., the left‐out infant was decoded as ASD if they had a latency that was larger than the threshold). Using the leave‐one‐out procedure, data were iterated 60 times, leaving out a different infant each time. The final reported accuracy rate was the percentage of accurately identified infants from each group. This analysis was performed using Matlab (Mathworks, Inc. 2013). In a final analysis, we used a chi‐square analysis to determine if there was a difference in the propensity for wave V prolongation as a function of group.

Results

Infant Group (Birth‐3 Months)

Absolute latencies and IPLs of the ABRs were compared between infants with ASD (n = 30) and case‐matched controls (n = 30) using a MANCOVA with testing age corrected for prematurity as the covariate. In comparison to matched‐case controls, infants who were later diagnosed with ASD exhibited significantly prolonged latencies of ABR wave V and the IPL of I–V in ABRs during stimulation of either the right or left ear [F(1,57) > 5.669, P < 0.022 and η2 > 0.089]. In addition, the IPL of III–V was prolonged when stimulating the right ear only [F(1,57)=4.513, P = 0.038 and η2 = 0.073]. The strongest difference across groups was noted in the absolute latency of wave V in the right ear [F(1,57) = 12.020, P = 0.001 and η2 = 0.174] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of ABR Mean Latencies Across Infants With ASD and Control Groups (Age 0–3 Months)

| ASD (n=30) | Case‐matched Controls (n=30) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ASD/C.M.Con MANCOVA (F) |

| Right Ear I | 1.61 | 0.07 | 1.61 | 0.26 | 0.037 |

| Right Ear III | 4.53 | 0.22 | 4.42 | 0.19 | 3.702 |

| Right Ear V | 6.76 | 0.21 | 6.54 | 0.26 | 12.020[Link] |

| Right Ear I–III | 2.92 | 0.21 | 2.81 | 0.28 | 2.960 |

| Right Ear III–V | 2.23 | 0.14 | 2.12 | 0.22 | 4.513[Link] |

| Right Ear I–V | 5.15 | 0.19 | 4.93 | 0.38 | 7.446[Link] |

| Left Ear I | 1.60 | 0.08 | 1.61 | 0.19 | .180 |

| Left Ear III | 4.57 | 0.23 | 4.46 | 0.20 | 3.481 |

| Left Ear V | 6.75 | 0.25 | 6.59 | 0.25 | 6.143[Link] |

| Left Ear I–III | 2.97 | 0.22 | 2.84 | 0.26 | 3.493 |

| Left Ear III–V | 2.19 | 0.16 | 2.13 | 0.18 | 1.540 |

| Left Ear I–V | 5.15 | 0.25 | 4.97 | 0.31 | 5.669[Link] |

*P < 0.05

**P < 0.01.

We then performed a classification analysis using a leave‐one‐out validation procedure (see methods) to examine how well ASD and control individuals could be identified according to the latency of ABR wave V. This analysis revealed that 21 of 30 ASD and 24 of 30 matched controls could be accurately identified according to the latency of ABR wave V during right ear stimulation. This yielded a positive predictive validity of 78% and negative predictive validity of 73%.

The propensity of infants later diagnosed with ASD that exhibit prolonged ABR wave V (70%) was higher than that of controls (20%), with the difference reaching significance in a Chi‐square analysis (ϰ2 = 15.152, P < 0.001). The classification odds ratios were 9.33 (confidence interval 2.874–30.602).

Toddler Group (1.5–3.5 Years)

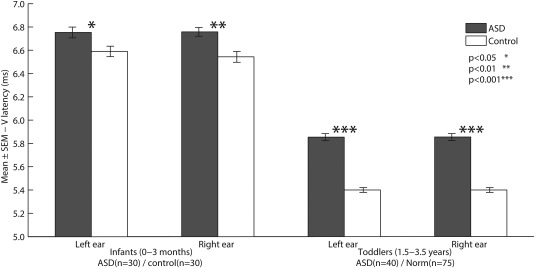

ABRs from the toddler group were also evaluated and compared with clinical norms [Roth et al., 2012] (Table 3). The latencies of ABR waves I, III, and V, as well as IPLs I‐III and I‐V of toddlers with ASD were significantly prolonged compared to clinical norms when stimulating either ear (t > 8.142, P < 0.001 for all measures). In addition, the latency of IPL III–V was prolonged in the ASD group when stimulating the right ear (t = 2.91; P = 0.006) and left ear (t = 2.43; P = 0.02) (Table 3). The latency of wave V was equal to or larger than 2 standard deviations of the clinical norms (5.76 ms) in 70% of the ASD participants when stimulated in the right ear and 67.5% when stimulated in the left ear. Sixty percent of ASD participants at this age range exhibited prolonged latencies regardless of which ear was stimulated. Wave V latency was therefore prolonged both in toddlers and in infants when stimulating the left or right ear (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Comparison of ABR Latencies Between Toddler ASD Group (Age 1.5–3.5 Years) and Clinical Norms

| ASD (n = 40) | Clinical norm (n = 75) | ASD vs. Norm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | T |

| Right Ear I | 1.51 | 0.07 | 1.4 | 0.09 | 9.73[Link] |

| Right Ear III | 3.90 | 0.14 | 3.6 | 0.16 | 12.43[Link] |

| Right Ear V | 5.85 | 0.18 | 5.4 | 0.18 | 15.26[Link] |

| Right Ear I–III | 2.39 | 1.45 | 2.1 | 0.16 | 12.62[Link] |

| Right Ear III–V | 1.95 | 0.11 | 1.9 | 0.18 | 2.91[Link] |

| Right Ear I–V | 4.33 | 0.16 | 4 | 0.2 | 13.22[Link] |

| Left Ear I | 1.50 | 0.08 | 1.4 | 0.09 | 8.14[Link] |

| Left Ear III | 3.91 | 0.14 | 3.6 | 0.16 | 13.35[Link] |

| Left Ear V | 5.85 | 0.18 | 5.4 | 0.18 | 15.22[Link] |

| Left Ear I–III | 2.40 | 1.28 | 2.1 | 0.16 | 15.05[Link] |

| Left Ear III–V | 1.94 | 0.11 | 1.9 | 0.18 | 2.43[Link] |

| Left Ear I–V | 4.35 | 0.16 | 4 | 0.2 | 13.81[Link] |

*P < 0.05

**P < 0.01

***P < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Shown is the mean wave‐V latency stimulating left or right ears at infancy (left bars) and toddlerhood (right bars). Black: ASD participants. White: Matched control participants (left bars) and control group norms [Roth et al., 2012](right bars). Error bars mark standard error of the mean. Asterisks denotes statistical significance using MANCOVA (left bars) or t‐tests (right bars); * denotes P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** denotes P < 0.001.

Discussion

The current study reveals that the majority of infants who later develop ASD exhibit abnormally prolonged ABRs already during the first three months of life, even when having normal hearing thresholds. This abnormality, which was evident in significant prolongation of ABR wave V latency in both the right and left ears, enabled accurate identification of infants who later developed ASD with 70% accuracy and that of controls with 80% accuracy. These results extend previous findings of abnormal social behaviors in high‐risk neonates with prolonged ABR [Cohen et al., 2013; Geva et al., 2013, 2011] and suggest that prolonged ABR latencies is a common characteristic of infants who later develop ASD. Furthermore, comparisons of ABR recordings from toddlers with ASD to clinical norms presented here and in previous studies [Roth et al., 2012] suggest that prolonged ABR latencies persist throughout early ASD development.

The underlying neuropathology that may account for the ABR prolongation in ASD remains unknown. One potential explanation is that prolonged wave V latencies are due to impaired progression rates of myelination of the auditory system in children with ASD, with some research pointing to marked delays [Perkins et al., 2014; Peterson, Mahajan, Crocetti, Mejia, & Mostofsky, 2014; Roberts et al., 2013; Wolff et al., 2012], while others suggest that white matter development is accelerated in ASD [Ben Bashat et al., 2007; Weinstein et al., 2011]. It is important to note, however, that the relevant neuroimaging studies performed to date have mostly concentrated on cerebral white matter tracts rather than explore white matter fibers traversing through the brainstem [Travers et al., 2015].

Several current theories of ASD neurophysiology have suggested that infants that develop ASD exhibit transient abnormalities during early critical periods of development that normalize at later ages (e.g., early brain overgrowth) [Amaral, Schumann, & Nordahl, 2008; Bailey et al., 1998; Courchesne et al., 2007]. Unlike other physiological findings, however, ABR abnormalities in ASD seem to already appear at birth and persist throughout early development, as reported in toddlers and older children [Dabbous, 2012; Fujikawa‐Brooks et al., 2010; Kwon et al., 2007; Maziade et al., 2000; Rosenhall et al., 2003; Russo et al., 2010; Tas et al., 2007; Wong & Wong, 1991]. Current results suggest that ABR abnormalities may be a relatively stable marker of ASD throughout development.

Recent magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies have reported that cortical responses to auditory stimuli are prolonged in children with ASD and in children with 16p11.2 deletions, which may also pertain to certain cases of ASD [Jenkins et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2010]. While these studies did not examine ABR recordings from the same children, it would be interesting to determine whether individuals with prolonged ABR also exhibit prolonged cortical auditory responses. Such deficits may have potential perceptual consequences and potentially alter the way information is processed in the ASD brain [Belmonte et al., 2004]. Another potential avenue of research would be to determine whether abnormal latencies of auditory neural responses may be linked in some way to auditory hyper or hypo sensitivities, which are common in ASD [American Psychiatric Association, 2013].

While the diagnosis of ASD is mostly based on social and communication capabilities, it is well acknowledged that individuals with ASD exhibit a wide variety of abnormalities in basic sensory and motor process [Karmel et al., 2010; Rosenhall, Nordin, Sandström, Ahlsen, & Gillberg, 1999]. In agreement with this notion, our results suggest that objective evidence for abnormal auditory processing were apparent already in the early stages of the auditory system during early ASD development. This supports the view of autism as a disorder characterized by widespread physiological abnormalities across multiple brain systems [Belmonte et al., 2004; Courchesne, Campbell, & Solso, 2011; Dinstein et al., 2012; Markram, Rinaldi, & Markram, 2007], rather than a specific dysfunction in a particular “high order” social brain network.

Some study limitations are that the examined groups were relatively small (i.e., n = 70: 30 infants and 40 toddlers with ASD). Additional ABR studies with healthy toddlers in the 1–4 year old age group are needed to address the gap in studies based on clinical samples. Furthermore, the ASD infants and toddlers who participated in the current study were referred for ABR testing due to a known risk for hearing impairment and/or neurodevelopmental delay. This sampling bias limits our ability to generalize the findings to other risk groups (e.g., ASD siblings) or cohorts with no known risk factors. ASD is an umbrella term for a constellation of different subtypes, and deeper examination of ABR characteristics as a function of particular symptoms, including examination of comorbid diagnoses, is warranted.

The reported results suggest a potential for the use of infant ABR recordings, not only for clinical assessment of hearing status, but also for estimating ASD risk. As many medical centers perform ABR exams routinely on every newborn at risk for hearing impairment [Morton & Nance, 2006; World Health Organization, 2010], large‐scale examination of the utility of these ABR exams for determining ASD risk is therefore, warranted and offers a promising direction for further research.

Acknowledgements

The research described here was supported by the Infra‐structure grant of the Ministry of Science, Space and Technology to R.G.; and the ISF and GIF grants to I.D. The research was prospectively reviewed and approved by a duly constituted ethics committee. Conflict of interest disclosure: All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Amaral, D. G. , Schumann, C. M. , & Nordahl, C. W. (2008). Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends in Neurosciences, 31, 137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American‐Psychiatric‐Association. (2000). DSM‐IV‐TR: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American‐Psychiatric‐Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐V (5th ed). Washington, DC: American‐Psychiatric‐Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, A. , Luthert, P. , Dean, A. , Harding, B. , Janota, I. , Montgomery, M. , Lantos, P ., et al. (1998). A clinicopathological study of autism. Brain, 121, 889–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte, M. K. , Allen, G. , Beckel‐Mitchener, A. , Boulanger, L. M. , Carper, R. A. , & Webb, S. J. (2004). Autism and abnormal development of brain connectivity. The Journal of Neuroscience, 24, 9228–9231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Bashat, D. , Kronfeld‐Duenias, V. , Zachor, D. A. , Ekstein, P. M. , Hendler, T. , Tarrasch, R. , Ben Sira, L. , et al. (2007). Accelerated maturation of white matter in young children with autism: A high b value DWI study. Neuroimage, 37, 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, I. L. , Gardner, J. M. , Karmel, B. Z. , Phan, H. T. , Kittler, P. , Gomez, T. R. , Barone, A. , et al. (2013). Neonatal brainstem function and 4‐month arousal‐modulated attention are jointly associated with autism. Autism Research, 6, 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne, E. , Campbell, K. , & Solso, S. (2011). Brain growth across the life span in autism: age‐specific changes in anatomical pathology. Brain Research, 1380, 138–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne, E. , Courchesne, R. Y. , Hicks, G. , & Lincoln, A. J. (1985). Functioning of the brain‐stem auditory pathway in non‐retarded autistic individuals. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 61, 491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne, E. , Pierce, K. , Schumann, C. M. , Redcay, E. , Buckwalter, J. A. , Kennedy, D. P. , Morgan, J. , et al. (2007). Mapping early brain development in autism. Neuron, 56, 399–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabbous, A. O. (2012). Characteristics of auditory brainstem response latencies in children with autism spectrum disorders. Audiological Medicine, 10, 122–131. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, G. , Rogers, S. , Munson, J. , Smith, M. , Winter, J. , Greenson, J. , Varley, J. , et al. (2010). Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics, 125, e17–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinstein, I. , Heeger, D. J. , Lorenzi, L. , Minshew, N. J. , Malach, R. , & Behrmann, M. (2012). Unreliable evoked responses in autism. Neuron, 75, 981–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa‐Brooks, S. , Isenberg, A. L. , Osann, K. , Spence, M. A. , & Gage, N. M. (2010). The effect of rate stress on the auditory brainstem response in autism: a preliminary report. International Journal of Audiology, 49, 129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geva, R. , Schreiber, J. , Segal‐Caspi, L. , & Markus‐Shiffman, M. (2013). Neonatal brainstem dysfunction after preterm birth predicts behavioral inhibition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(7), 802–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geva, R. , Sopher, K. , Kurtzman, L. , Galili, G. , Feldman, R. , & Kuint, J. (2011). Neonatal brainstem dysfunction risks infant social engagement. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(2), 158–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecox, K. , & Galambos, R. (1974). Brain stem auditory evoked responses in human infants and adults. Archives of Otolaryngology, 99, 30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, J. , Chow, V. , Blaskey, L. , Kuschner, E. , Qasmieh, S. , Gaetz, L. , Roberts, T. P. , et al. (2015). Auditory Evoked M100 Response Latency is Delayed in Children with 16p11. 2 Deletion but not 16p11. 2 Duplication. Cerebral Cortex. pii: bhv008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S. , Hollis, C. , Kochhar, P. , Hennessy, E. , Wolke, D. , & Marlow, N. (2010). Autism spectrum disorders in extremely preterm children. Journal of Pediatrics, 156, 525–531. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint‐Committee‐on‐Infant‐Hearing . (2007). Year 2007 Position Statement: Principles and Guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Programs. Pediatrics, 120(4), 898–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmel, B. Z. , Gardner, J. M. , Meade, L. S. , Cohen, I. L. , London, E. , Flory, M. J. , Harin, A. , et al. (2010). Early medical and behavioral characteristics of NICU infants later classified with ASD. Pediatrics, 126, 457–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmel, B. Z. , Gardner, J. M. , Zappulla, R. A. , Magnano, C. L. , & Brown, E. G. (1988). Brain‐stem auditory evoked responses as indicators of early brain insult. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology/Evoked Potentials Section, 71, 429–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S. , Kim, J. , Choe, B.‐H. , Ko, C. , & Park, S. (2007). Electrophysiologic assessment of central auditory processing by auditory brainstem responses in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 22, 656–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram, H. , Rinaldi, T. , & Markram, K. (2007). The intense world syndrome–an alternative hypothesis for autism. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 1(1), 77–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maziade, M. , Mérette, C. , Cayer, M. , Roy, M.‐A. , Szatmari, P. , Côté, R. , Thivierge, J. , et al. (2000). Prolongation of brainstem auditory‐evoked responses in autistic probands and their unaffected relatives. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 1077–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton, C. C. , & Nance, W. E. (2006). Newborn hearing screening: A silent revolution. New England Journal of Medicine, 354, 2151–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, T. J. , Stokes, M. A. , McGillivray, J. A. , Mussap, A. J. , Cox, I. A. , Maller, J. J. , Bittar, R. G. , et al. (2014). Increased left hemisphere impairment in high‐functioning autism: A tract based spatial statistics study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 224, 119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, D. , Mahajan, R. , Crocetti, D. , Mejia, A. , & Mostofsky, S. (2014). Left‐hemispheric microstructural abnormalities in children with high‐functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 8(1), 61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, T. P. , Khan, S. Y. , Rey, M. , Monroe, J. F. , Cannon, K. , Blaskey, L. , Edgar, J. G. , et al. (2010). MEG detection of delayed auditory evoked responses in autism spectrum disorders: Towards an imaging biomarker for autism. Autism Research, 3, 8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, T. P. , Lanza, M. R. , Dell, J. , Qasmieh, S. , Hines, K. , Blaskey, L. , Berman, J. I. , et al. (2013). Maturational differences in thalamocortical white matter microstructure and auditory evoked response latencies in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Research, 1537, 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenhall, U. , Nordin, V. , Brantberg, K. , & Gillberg, C. (2003). Autism and auditory brain stem responses. Ear and Hearing, 24, 206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenhall, U. , Nordin, V. , Sandström, M. , Ahlsen, G. , & Gillberg, C. (1999). Autism and hearing loss. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 29, 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth, D. A. E. , Muchnik, C. , Shabtai, E. , Hildesheimer, M. , & Henkin, Y. (2012). Evidence for atypical auditory brainstem responses in young children with suspected autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 54, 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo, N. M. , Hornickel, J. , Nicol, T. , Zecker, S. , & Kraus, N. (2010). Biological changes in auditory function following training in children with autism spectrum disorders. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 6, 60, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schendel, D. , & Bhasin, T. K. (2008). Birth weight and gestational age characteristics of children with autism, including a comparison with other developmental disabilities. Pediatrics, 121, 1155–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tas, A. , Yagiz, R. , Tas, M. , Esme, M. , Uzun, C. , & Karasalihoglu, A. R. (2007). Evaluation of hearing in children with autism by using TEOAE and ABR. Autism, 11, 73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharpe, A. M. , Bess, F. H. , Sladen, D. P. , Schissel, H. , Couch, S. , & Schery, T. (2006). Auditory characteristics of children with autism. Ear and Hearing, 27, 430–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thivierge, J. , Bédard, C. , Côté, R. , & Maziade, M. (1990). Brainstem auditory evoked response and subcortical abnormalities in autism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147(12), 1609–1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers, B. G. , Bigler, E. D. , Tromp, D. P. , Adluru, N. , Destiche, D. , Samsin, D. , Lainhart, J. E. , et al. (2015). Brainstem White Matter Predicts Individual Differences in Manual Motor Difficulties and Symptom Severity in Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(9), 3030–3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar, F. , Siegel, M. , Woodbury‐Smith, M. , King, B. , McCracken, J. , & State, M. (2014). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53, 237–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, M. , Ben‐Sira, L. , Levy, Y. , Zachor, D. A. , Itzhak, E. B. , Artzi, M. , Ben Bashat, D. , et al. (2011). Abnormal white matter integrity in young children with autism. Human Brain Mapping, 32, 534–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J. J. , Gu, H. , Gerig, G. , Elison, J. T. , Styner, M. , Gouttard, S. , Piven, J ; IBIS Network. et al. (2012). Differences in white matter fiber tract development present from 6 to 24 months in infants with autism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, V. , & Wong, S. N. (1991). Brainstem auditory evoked potential study in children with autistic disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 21, 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World‐Health‐Organization . (2010). Newborn and infant hearing screening ‐ Current issues and guiding principels for action outcome of a WHO informal consultation, Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]