Abstract

Objective

To explore the safety and tolerability of atacicept in combination with rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA) receiving rituximab re‐treatment.

Methods

In this randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled pilot trial, 2 infusions (1,000 mg per infusion) of intravenous rituximab, given 2 weeks apart, were followed by once‐weekly subcutaneous injections of 150 mg atacicept or placebo for 25 weeks. Primary end points were the nature, incidence, and severity of adverse events (AEs). Secondary end points were the effects on peripheral blood B cells, disease activity biomarkers, and American College of Rheumatology 20% (ACR20), 50% (ACR50), and 70% (ACR70) response rates.

Results

Eighteen patients were randomized to receive atacicept and 9 to receive placebo. AEs occurred in 17 atacicept‐treated patients (94.4%) and in all 9 placebo‐treated patients (100%). There were no infection‐related serious adverse events. Hypersensitivity and injection site reactions were more common, and more patients withdrew due to AEs, in the atacicept group. Median reductions in Ig levels from baseline to week 32 were greater with atacicept (median change in IgG −31.2%, IgM −60.9%, and IgA −56.4%) than with placebo (median change in IgG −4.4%, IgM −15.9%, and IgA −8.2%). Peripheral B cell numbers remained low in all patients after rituximab‐mediated B cell depletion, limiting comparison of time to recovery between treatment groups. There were no between‐group differences in ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 response rates.

Conclusion

In this exploratory trial, atacicept in combination with rituximab showed no new safety issues. Peripheral B cell counts remained too low to determine whether atacicept delayed B cell re‐expansion following rituximab‐mediated depletion. Despite clear biologic effects, adding atacicept to rituximab in patients with active RA was not associated with clinical benefit.

Use of the B cell–depleting agent rituximab results in clinical improvements in disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) 1, 2, 3, providing proof‐of‐concept for the importance of B cells in the pathogenesis of this chronic inflammatory autoimmune disorder 4. B cells act as antigen‐presenting cells, secrete proinflammatory cytokines, and produce autoantibodies in RA 4. In spite of the efficacy of rituximab in RA, not all patients respond 5, 6. Lack of response is associated with persistence of B‐lineage cells, in particular plasma cells, at the site of inflammation, the synovium 7.

The persistence of B‐lineage cells in the synovial tissue may be associated with increased levels of the B cell maturation/survival factors B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) and APRIL (a proliferation‐inducing ligand) 8, 9, 10. Importantly, serum BLyS levels rise sharply following B cell depletion by rituximab, returning to normal only after B cells recover to baseline levels 11. This supports the hypothesis that the beneficial effects of rituximab may be limited by the survival or re‐expansion of autoreactive B‐lineage cells supported by BLyS. It has previously been suggested that interfering with APRIL and BLyS may help to optimize the clinical response to rituximab treatment in RA 7. This could be achieved by treatment with atacicept, which is a soluble, fully human recombinant fusion protein that neutralizes the activity of BLyS and APRIL 12, 13.

In clinical trials featuring combinations of other biologic agents, an increased risk of infections has been observed 14, 15. The present study, the Atacicept for Reduction of Signs and Symptoms in Rheumatoid Arthritis Trial III (AUGUST III), was an exploratory study with the primary objective of assessing the safety and tolerability of atacicept in patients with active RA receiving rituximab re‐treatment. Secondary objectives focused on evaluating the effects of combination treatment with atacicept and rituximab on the proportions of peripheral B cell populations, levels of biomarkers reflecting disease activity and drug‐related mechanisms of action, and measures of efficacy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design

In this multicenter, phase II, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled pilot trial (AUGUST III), we assessed the safety and tolerability of atacicept in combination with rituximab re‐treatment in patients with moderate or severe RA. The study comprised a 7‐week rituximab treatment period, a 25‐week atacicept/placebo treatment period, and a 32‐week posttreatment followup period. In the rituximab period, all patients received two 1000‐mg doses of rituximab by intravenous infusion, 2 weeks apart (weeks 1 and 3). At week 7 (after 28 days without treatment), patients were randomized 2:1 to receive subcutaneous atacicept at a dose of 150 mg or placebo, once weekly for 25 weeks. Randomization was stratified by rheumatoid factor (RF) status (positive or negative) and country, and an interactive voice response system was used to allocate treatment kit numbers.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards and independent Ethics Committees at the participating institutions, and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines, and any local requirements. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study population

The study population consisted of male and female patients ages ≥18 years who had been diagnosed as having RA according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1987 revised criteria 16, had a disease duration of ≥12 months, had previously responded to treatment with rituximab, and had residual disease activity. The patients were recruited from multiple European sites and were treated on an outpatient basis. Patients had to have a Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) of >3.2 17, with a documented response to, and good tolerance of, previous rituximab treatment. They also were required to have significant residual disease (DAS28 >3.2) or clinical deterioration (an increase of ≥0.6 in the DAS28) after such treatment.

Patients were not eligible for inclusion if they had an inflammatory joint disease other than RA, had displayed any contraindication to rituximab, had received disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug therapy for <3 months or changed their regimen within 28 days of study day 1, had received either methotrexate at a dosage of >25 mg/week, an anti–tumor necrosis factor agent (anakinra or tocilizumab) within 12 weeks of study day 1, or abatacept or another cell‐depleting therapy within 24 weeks of study day 1, or had received prednisone at a dosage of >10 mg/day or changed their steroid dosage within 28 days of day 1. One intraarticular steroid injection during each of the screening and treatment periods was permitted.

Study end points

Primary safety end points included the following: the nature, incidence, and severity of adverse events (AEs), particularly infection‐related AEs; the proportion of patients with an IgG level of <3 gm/liter; changes over time and abnormalities in vital signs and routine safety laboratory parameters; and changes over time in immunization status (titers of antibodies against tetanus toxoid, pneumococcus, and diphtheria toxin).

Secondary end points included the following: changes over time in the proportion of peripheral B cell populations; changes over time in markers of disease activity, consisting of concentrations of C‐reactive protein (CRP), the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and RF status, together with other ACR core set measures and the severity of morning stiffness, all comprising variables that enabled calculation of the ACR 20% [ACR20], ACR50, and ACR70 composite scores of improvement response [18]); and changes over time in the levels of IgG, IgM, and IgA. To preserve blinding, all joint evaluations were performed by independent efficacy assessors.

Statistical analysis

As this was an exploratory pilot study, sample size was not based on formal calculations of statistical power. Data were summarized using descriptive statistics. The safety analysis was performed in the safety population, which included all patients who had received at least one dose of atacicept or placebo and for whom followup safety data were available. The intent‐to‐treat (ITT) population was identical to the safety population.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

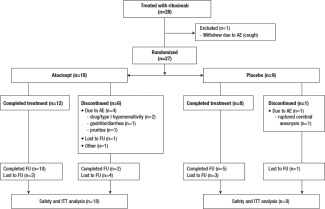

This study was conducted between March 25, 2008 and January 26, 2011. Twenty‐eight patients were enrolled and treated with rituximab. Of these patients, 27 were randomized to receive atacicept (n = 18) or placebo (n = 9) and were included in the safety and ITT analyses (Figure 1). Patient demographics and disposition were similar between the groups, except that there were more women in the atacicept group (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Disposition of the study patients treated with two 1,000‐mg infusions of rituximab given 2 weeks apart, followed by 150 mg atacicept or placebo given once weekly for 25 weeks. AE = adverse event; FU = followup; ITT = intent‐to‐treat.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study patientsa

| Rituximab then atacicept (n = 18) | Rituximab then placebo (n = 9) | Overall (n = 27) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 57.0 ± 11.0 | 57.7 ± 11.5 | 57.2 ± 11.0 |

| Female, no. (%) | 12 (66.7) | 8 (88.9) | 20 (74.1) |

| Weight, kg | 76.5 ± 15.0 | 74.9 ± 17.1 | 76.0 ± 15.4 |

| Disease duration, years | 12.3 ± 5.6 | 13.0 ± 5.8 | 12.6 ± 5.5 |

| RF positive, no. (%) | 17 (94.4) | 8 (88.9) | 25 (92.6) |

| Oral corticosteroid use, no. (%) | 13 (72.2) | 6 (66.7) | 19 (70.4) |

| Methotrexate use, no. (%) | 12 (66.7) | 7 (77.8) | 19 (70.4) |

| CRP, mg/liter | 28.9 ± 35.2 | 36.2 ± 36.8 | 31.3 ± 35.2 |

| ESR, mm/hour | 34.4 ± 22.8 | 42.1 ± 23.1 | 37.0 ± 22.8 |

| DAS28‐CRP | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 5.8 ± 1.0 | 5.6 ± 1.0 |

Except where indicated otherwise, values are the mean ± SD. RF = rheumatoid factor; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; DAS28‐CRP = Disease Activity Score in 28 joints based on the C‐reactive protein (CRP) level.

Among the randomized patients, 4 (22.2%) in the atacicept group and 5 (55.6%) in the placebo group were re‐treated with rituximab during the posttreatment followup period, at the discretion of the treating physician. This imbalanced randomization posed a risk to the trial and to the identification of causality of AEs.

Primary end points

Safety

Atacicept/placebo treatment period

The majority of AEs were reported during the 25‐week atacicept/placebo treatment period, during which 295 AEs were reported by 26 (96.3%) of the 27 randomized patients (Table 2). The AEs were mostly mild or moderate in intensity and occurred with similar frequency across both treatment groups (17 patients [94.4%] in the atacicept group and 9 patients [100%] in the placebo group). Three patients experienced a total of 4 serious AEs (SAEs) during the atacicept/placebo treatment period: 2 in the placebo group (transient ischemic attack [TIA], ruptured cerebral aneurysm) and 1 in the atacicept group (drug hypersensitivity and TIA).

Table 2.

Incidence of SAEs and AEs during the 25‐week atacicept/placebo treatment period (safety population)a

| Type of event, system | Rituximab then atacicept | Rituximab then placebo | Overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| organ class preferred term | Patients | Events | Patients | Events | Patients | Events |

| SAEs | ||||||

| All | 1/18 (5.6) | 2/2 (100.0) | 2/9 (22.2) | 2/2 (100.0) | 3/27 (11.1) | 4/4 (100.0) |

| Nervous system disorders Transient ischemic attack | 1/18 (5.6) | 1/2 (50.0) | 1/9 (11.1) | 1/2 (50.0) | 2/27 (7.4) | 2/4 (50.0) |

| Ruptured cerebral aneurysm | 1/9 (11.1) | 1/2 (50.0) | 1/27 (3.7) | 1/4 (25.0) | ||

| Immune system disorders, drug hypersensitivity | 1/18 (5.6) | 1/2 (50.0) | 0 | 0 | 1/27 (3.7) | 1/4 (25.0) |

| AEs | ||||||

| All | 17/18 (94.4) | 241/241 (100.0) | 9/9 (100.0) | 54/54 (100.0) | 26/27 (96.3) | 295/295 (100.0) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 13/18 (72.2) | 156/241 (64.7) | 4/9 (44.4) | 20/54 (37.0) | 17/27 (63.0) | 176/295 (59.7) |

| Infections and infestations | 8/18 (44.4) | 11/241 (4.6) | 6/9 (66.7) | 10/54 (18.5) | 14/27 (51.9) | 21/295 (7.1) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 6/18 (33.3) | 6/241 (2.5) | 5/9 (55.6) | 5/54 (9.3) | 11/27 (40.7) | 11/295 (3.7) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 8/18 (44.4) | 16/241 (6.6) | 2/9 (22.2) | 2/54 (3.7) | 10/27 (37.0) | 18/295 (6.1) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 5/18 (27.8) | 10/241 (4.1) | 3/9 (33.3) | 3/54 (5.6) | 8/27 (29.6) | 13/295 (4.4) |

| Nervous system disorders | 3/18 (16.7) | 8/241 (3.3) | 4/9 (44.4) | 8/54 (14.8) | 7/27 (25.9) | 16/295 (5.4) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 3/18 (16.7) | 22/241 (9.1) | 3/9 (33.3) | 3/54 (5.6) | 6/27 (22.2) | 25/295 (8.5) |

| Immune system disorders | 4/18 (22.2) | 4/241 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 4/27 (14.8) | 4/295 (1.4) |

| Eye disorders | 3/18 (16.7) | 3/241 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 3/27 (11.1) | 3/295 (1.0) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | 2/18 (11.1) | 3/241 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 2/27 (7.4) | 3/295 (1.0) |

| Vascular disorders | 1/18 (5.6) | 1/241 (0.4) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (7.4) | 2/295 (0.7) |

| Cardiac disorders | 1/18 (5.6) | 1/241 (0.4) | 1 (3.7) | 1/295 (0.3) | ||

| Investigationsb | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (3.7) | 1/295 (0.3) |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (3.7) | 1/295 (0.3) |

Serious adverse events (SAEs) and AEs were evaluated in the safety population (comprising patients who were randomized and received at least one study treatment dose and for whom safety data were available; n = 27). The atacicept period ranged from the date of the first atacicept/placebo dose to the date of the last atacicept/placebo dose plus 7 days. AEs were coded using MedDRA version 13.0. Values are the number/total number (percentage) of patients or events.

Defined as laboratory abnormalities.

AEs leading to discontinuation were more frequent in the atacicept group than in the placebo group: 4 patients (22.2%) in the atacicept group (2 patients with a drug/type I hypersensitivity reaction, 1 patient with diarrhea and gastritis, and 1 patient with pruritus), and 1 patient (11.1%) in the placebo group (ruptured cerebral aneurysm).

Fewer infections occurred in the atacicept group (8 patients [44.4%] experienced 11 events) compared to the placebo group (6 patients [66.7%] experienced 10 events), and generally these represented commonly encountered infections: upper respiratory tract infection, influenza, nasopharyngitis, conjunctivitis, rhinitis, hordeolum, and urinary tract infection. There were no infection‐related SAEs during the treatment period.

Local injection‐site reactions were more frequent in atacicept‐treated patients (11 [61.1%]) than in placebo‐treated patients (2 [22.2%]). These reactions were consistent with those observed in previous studies of patients treated with atacicept 19 and comprised mild‐to‐moderate erythema, itching, and swelling.

Hypersensitivity reactions were more frequent in atacicept‐treated patients (9 [50.0%]) than in placebo‐treated patients (2 [22.2%]), and led to withdrawal in 2 atacicept‐treated patients. Six of the atacicept‐treated patients with hypersensitivity‐related events had skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (including pruritus), 4 (22.2%) had immune system disorders (including drug hypersensitivity and type I hypersensitivity), and 2 (11.1%) had respiratory disorders (cough and dyspnea).

Followup period

Six patients in the atacicept group experienced a total of 12 SAEs during the nontreatment followup period, distributed as follows: 1 patient with atrial fibrillation, 1 patient with cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrillation, 1 patient with pelvic fracture, joint capsule rupture, and arthropathy, 1 patient with visual impairment and muscular weakness, 1 patient with gastroenteritis, and 1 patient with demyelination, glioma, and nervous system disorder. This latter SAE occurred in a 30‐year‐old female patient who had no history of demyelinating disease. This patient experienced a suspected focal glioma or focal demyelination in the cerebellum, with symptoms beginning ∼3 months after atacicept treatment, which led to hospitalization. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a stable, nonprogressing lesion in the right cerebellum and medically significant multifocal changes of vascular origin in the white matter of both hemispheres. Symptoms did not progress over 6 months of followup. As of January 3, 2014, the investigator confirmed that this patient was still under his supervision, and no new neurologic signs and symptoms were present. The patient was doing well under a treatment regimen of biologic agents. With the exception of this patient, SAEs resolved in all other patients. No trends in the nature of the SAEs reported were observed in patients treated with atacicept.

Immunologic status

A reduction in IgG levels to <3 gm/liter was not observed in any patients, and there were no notable changes in clinical or laboratory parameters in any patients throughout the study treatment period. The median antibody titers at week 32 were reduced from baseline in the atacicept‐treated patients but not in the placebo‐treated patients, with median changes from baseline in the atacicept group versus the placebo group as follows: for anti–tetanus toxoid, −18.0% (interquartile range [IQR] −34.29, 0.00) versus 0.0% (IQR −7.67, 23.68); for anti–diphtheria toxin, −33.7% (IQR −50.00, 0.00) versus 8.4% (IQR 0.00, 0.00); and for antipneumococcus, −18.5% (IQR −35.18, 0.00) versus 0.0% (IQR 0.39, 33.93). These values returned to close to baseline levels by week 16 of the followup period. There were few shifts to below‐protective antibody titers, and there were no between‐group differences with respect to the frequency of shifts.

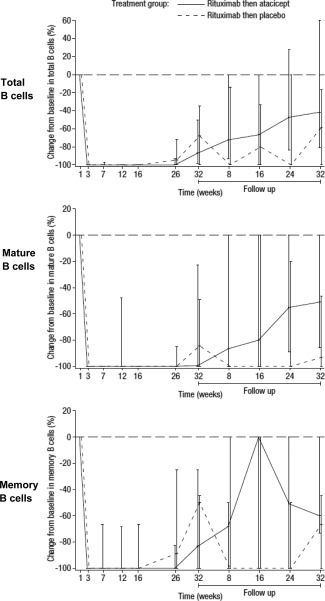

Secondary end points

Figure 2 shows the median percentage change in the levels of total, mature, and memory B cells over time. Following treatment with rituximab, the median levels of total, mature, and memory B cells were reduced to 0 (total B cells, median 0 [range 0–2.0 cells/mm3]; mature B cells, median 0 [range 0–0 cells/mm3]; and memory B cells, median 0 [range 0–1.0 cells/mm3]), and little recovery of B cells was observed in either treatment group. Mature B cell recovery at week 64 was <10% in the placebo group and ∼50% in the atacicept group. There were no notable differences in the proportions of T cells between treatment groups; median total T cell levels at week 32 in the atacicept and placebo treatment groups were 1,051/mm3 and 1,124/mm3, respectively, whereas the median levels of T helper cells were 769.5/mm3 and 744/mm3, respectively.

Figure 2.

Change in the levels of total, mature, and memory B cells over time in patients treated with two 1,000‐mg infusions of rituximab given 2 weeks apart, followed by 150 mg atacicept or placebo given once weekly for 25 weeks. Values are the percentage change from baseline, expressed as the median with interquartile range. The horizontal broken line indicates baseline.

Combination treatment with atacicept was not associated with a greater decrease in the CRP level compared to re‐treatment with rituximab alone. Reductions from baseline in the median ESR were numerically greater with atacicept compared to placebo from week 12 onward, with the greatest difference observed at week 32 (see Supplementary Table 1, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39262/abstract). The greatest reductions in the median levels of IgG‐RF, IgM‐RF and IgA‐RF were observed at week 32, and these reductions were all numerically greater with atacicept (see Supplementary Table 2, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39262/abstract).

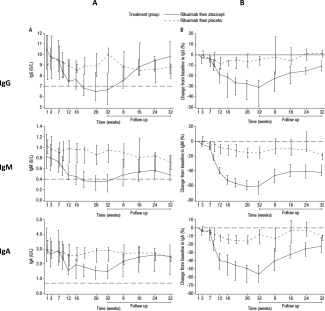

Treatment with atacicept was associated with greater median reductions from baseline to week 32 in the levels of IgG, IgM, and IgA (median change from baseline −31.2% [IQR −49.6, −24.1], −60.9% [IQR −71.88, −54.43]), and −56.4% [IQR −66.84, −45.49], respectively) compared to placebo (median change from baseline −4.4% [IQR −10.17, −1.32], −15.9% [IQR −22.92, −7.82], and −8.2% [IQR −19.69, −2.02], respectively) (Figure 3). Median IgG and IgM levels were below the lower limits of normal in the atacicept group from week 20 to week 32. The median IgG levels recovered after cessation of treatment, to reach levels that were 10.9% lower than those at baseline by followup at week 64. However, the median IgM levels had not recovered in all patients by the end of the followup period.

Figure 3.

Change in levels of IgG, IgM, and IgA from baseline to week 32 in patients treated with two 1,000‐mg infusions of rituximab given 2 weeks apart, followed by 150 mg atacicept or placebo given once weekly for 25 weeks. In A, values are the levels of each immunoglobulin (in gm/liter) over time. The horizontal broken line indicates the lower limit of normal. In B, values are the percentage change from baseline. The horizontal broken line indicates baseline. All results are expressed as the median with interquartile range.

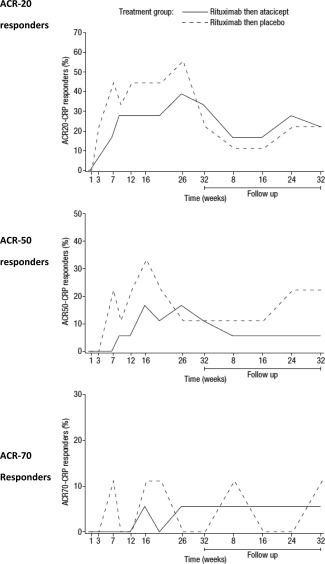

Clinical efficacy

There were no noteworthy between‐group differences in clinical response to treatment over time, as defined by the ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 improvement response criteria based on the CRP level (Figure 4). The mean DAS28 (based on the CRP level or ESR) remained below the values observed at baseline from week 7 onward in both treatment groups (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Proportion of patients responding to combination treatment with atacicept versus those treated with placebo over time. Patients were treated with two 1,000‐mg infusions of rituximab given 2 weeks apart, followed by 150 mg atacicept or placebo given once weekly for 25 weeks. Responses were defined according to the American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement criteria (ACR20), the ACR50, and the ACR70 based on the C‐reative protein (CRP) level.

DISCUSSION

In this phase II pilot study of atacicept in combination with rituximab re‐treatment in patients with moderate to severe RA, the safety profile of atacicept was consistent with previous experience, and no new safety trends were observed 15, 20. AEs were common (driven mainly by injection‐site reactions and infections), were mostly mild or moderate, and occurred with a similar frequency in both the active treatment and placebo groups.

SAEs occurred in 8 patients during the study: 2 in the treatment period, 1 during the treatment and followup periods, and 5 during followup. The SAEs that occurred during followup were observed in patients who had received atacicept. There were, however, no notable trends in the types of SAEs that emerged, and all except one (focal demyelination/glioma) resolved. This patient developed a focal demyelination and demonstrated multifocal changes in the white matter on MRI, which did not progress over a 6‐month period, and symptoms did not progress over 4 years of followup.

The etiology of the white matter lesions identified by MRI in this patient is not clear, although the changes are consistent with a demyelinating process and ischemic changes. It should be noted that demyelination due to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) following rituximab treatment in RA patients, leading to estimates of increased risk in the order of 1 per 25,000 patients treated, has been reported in the literature 21. Rituximab‐induced depletion of B cells has been suggested to permit the reactivation of JC virus (JCV), which is responsible for PML 21. However, the JCV status of the patients in the present study was not investigated. In a clinical trial of patients with multiple sclerosis, atacicept treatment was associated with exacerbation of the disease. However, there have been no new diagnoses of demyelinating processes reported in any other atacicept clinical trial. It is not possible to tell from this small pilot study whether atacicept contributed to the demyelination event in this patient. The investigator, however, considered the focal demyelination, suspected focal glioma, and multifocal changes in the white matter to be either unrelated or unlikely to be related to the study medication. RA itself was reported as an alternative explanation for this SAE.

Infection‐related AEs observed in this study were mostly infections that are commonly encountered, consistent with previous reports 15, 20. The infection rate was slightly higher than that previously reported to be associated with treatment with atacicept (44% in the present study versus 34–35% in prior studies [15,20]), but was still lower than that in patients treated with rituximab alone (66.7%). Rituximab re‐treatment has been associated with a reported rate of infection of 50–60% in clinical trials 22, 23. Thus, re‐treatment with rituximab may be contributing to the higher infection rate seen in patients also treated with atacicept. Importantly, no serious infections were reported among atacicept‐treated patients during the treatment period, despite the clear effect of atacicept on B cell levels established in other clinical trials of atacicept in RA patients; one event of severe gastroenteritis occurred 4 months after treatment in a patient who had recently visited Thailand.

The percentage of patients who withdrew due to AEs was twice as high with atacicept as with placebo. Injection‐site reactions with atacicept were more frequent than previously reported (72.2% in the present study versus 10–11% in prior studies [19,20]), and the incidence of hypersensitivity reactions was also higher in atacicept‐treated patients (50.0%) than in placebo‐treated patients (22.2%). The reasons for this remain unclear; the small sample size could have led to chance results, or rituximab could have increased hypersensitivity to atacicept.

As in other phase I and phase II trials 15, 20, atacicept was not associated with an increased rate of total infection, despite its Ig‐lowering effects. A small reduction in antibody titers was observed. The reduction in protective titers was, however, not greater than the reduction in total IgG levels. There was no apparent correlation between patients with infections and those with the lowest mean levels of each Ig subclass (data not shown).

Atacicept demonstrated marked biologic activity, as indicated by the decreases in the ESR, B cell subset counts, and concentrations of Ig subclasses and RF in atacicept‐treated patients compared to placebo‐treated patients. The magnitude and pattern of the decrease in total Ig levels following treatment with rituximab and atacicept were similar to those observed in previous RA trials with atacicept alone 15, 20. Consistent with those earlier studies, atacicept‐associated reductions in the ESR were greater than the reductions in the CRP level, which may be attributed to the reduction in total Ig levels associated with atacicept 15, 20. As expected, B cell subsets in the peripheral blood were completely depleted by rituximab, but there was no indication that atacicept delayed the recovery of B cell populations. In some cases, particularly for mature B cells, recovery was quicker following atacicept treatment compared to placebo treatment. Interpretation of these data is, however, limited by a high degree of interindividual variability, the small study size, very low starting numbers of lymphocyte cell populations (typically <10 cells/mm3, with a resolution of 1 cell/mm3), and a between‐group difference in the proportion of patients who received rituximab re‐treatment during followup, which was numerically higher in the placebo group.

The mechanisms of action of rituximab and atacicept on B cell populations are understood to be complementary, suggesting a potential for additive or synergistic clinical benefit following their combination 7, 11, 12. However, no treatment benefit, as measured by the ACR response rates and DAS28, was observed following the addition of atacicept to rituximab re‐treatment in this study. Published phase II studies of atacicept in RA have previously demonstrated only modest clinical effects despite considerable biologic activity 15, 20. The reasons for this disparity remain unclear. BLyS and APRIL may regulate both B cell and T cell function, and could have both proinflammatory and antiinflammatory activities in RA 24. The possibility also exists that atacicept did not sufficiently block BLyS and APRIL locally in the synovium, leading to insufficient local reduction of B cells and plasma cells. In addition, it is possible that sequential therapy that starts with atacicept first, in order to mobilize memory B cells from niche compartments, followed by rituximab could have higher therapeutic benefit.

In this study, the rates of clinical response to rituximab were lower than those previously reported 1, 2. Patients in other studies had not been previously treated with rituximab at baseline, and thus may have had a larger response than those being re‐treated in the present study. Patients in this study may have experienced some residual therapeutic effect, meaning that re‐treatment with rituximab did not lower the CRP level as much as initial treatment.

The number of patients who were re‐treated with rituximab was lower in the atacicept group compared to the placebo group; thus, there is a possibility that atacicept treatment was associated with a more persistent response. Indeed, this was the original hypothesis that led to this trial. Unfortunately, no other measured outcome provides independent support for this hypothesis, and so it remains an intriguing possibility, at best. The study limitations included the small numbers of patients in each group, and the short duration of this pilot study.

In conclusion, this pilot study demonstrated that administering atacicept following rituximab re‐treatment presented no new safety concerns and was associated with an AE profile consistent with that reported previously for atacicept in phase II studies. Atacicept exerted clear biologic effects, but no additional clinical benefit was observed. Any evidence of an effect of atacicept on delayed B cell re‐expansion following rituximab‐mediated depletion could not be evaluated, since there was virtually no recovery of B cells in the placebo group during the followup period. These findings, therefore, do not suggest that the combination of atacicept and rituximab should be pursued as a therapeutic option for patients with RA.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. van Vollenhoven had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. van Vollenhoven, Wax, Li, Tak.

Acquisition of data. van Vollenhoven, Wax, Li, Tak.

Analysis and interpretation of data. van Vollenhoven, Wax, Li, Tak.

ROLE OF THE STUDY SPONSOR

Merck Serono was involved in the study design and in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data. Authors Wax and Li are employees of EMD Serono and were involved in writing the manuscript. All authors were jointed involved in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Publication of the article was not contingent upon approval by Merck Serono.

ADDITIONAL DISCLOSURES

Author Tak is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table 1. C‐reactive protein (CRP) levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) in patients treated with 1,000 mg rituximab followed by once‐weekly 150 mg atacicept or placebo

Supplementary Table 2. Levels of Ig–rheumatoid factor in patients treated with 1,000 mg rituximab followed by once‐weekly 150 mg atacicept or placebo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marieke Herenius, MD and Danielle M. Gerlag, MD, PhD for including patients from the Academic Medical Center/University of Amsterdam. We also thank all patients and their families for their participation in the study. Editorial assistance and medical writing support were provided by Linda Edmondson, Paul FitzGerald, and Jose Heroys of Syntropy Medica Ltd. (Worthing, UK), which was supported by EMD Serono Inc. (Rockland, MA), a subsidiary of Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany), and by Sharon Cato, Yasmeen Arif, and Helen Clarke of Discovery London (London, UK), which was supported by Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany).

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00664521.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, Dougados M, Furie RA, Genovese MC, et al, for the REFLEX Trial Group. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty‐four weeks. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Emery P, Fleischmann R, Filipowicz‐Sosnowska A, Schechtman J, Szczepanski L, Kavanaugh A, et al, for the DANCER Study Group . The efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate treatment: results of a phase IIb randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, dose‐ranging trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tak PP, Rigby W, Rubbert‐Roth A, Peterfy C, van Vollenhoven RF, Stohl W, et al. Sustained inhibition of progressive joint damage with rituximab plus methotrexate in early active rheumatoid arthritis: 2‐year results from the randomised controlled trial IMAGE. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:351–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bugatti S, Codullo V, Caporali R, Montecucco C. B cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev 2007;7:137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vital EM, Dass S, Rawstron AC, Buch MH, Goeb V, Henshaw K, et al. Management of nonresponse to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis: predictors and outcome of re‐treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:1273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raterman HG, Vosslamber S, de Ridder S, Nurmohamed MT, Lems WF, Boers M, et al. The interferon type I signature towards prediction of non‐response to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Res Ther 2012;14:R95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thurlings RM, Vos K, Wijbrandts CA, Zwinderman AH, Gerlag DM, Tak PP. Synovial tissue response to rituximab: mechanism of action and identification of biomarkers of response. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:917–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dorner T, Kinnman N, Tak PP. Targeting B cells in immune‐mediated inflammatory disease: a comprehensive review of mechanisms of action and identification of biomarkers. Pharmacol Ther 2010;125:464–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheema GS, Roschke V, Hilbert DM, Stohl W. Elevated serum B lymphocyte stimulator levels in patients with systemic immune-based rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tan SM, Xu D, Roschke V, Perry JW, Arkfeld DG, Ehresmann GR, et al. Local production of B lymphocyte stimulator protein and APRIL in arthritic joints of patients with inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:982–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cambridge G, Stohl W, Leandro MJ, Migone TS, Hilbert DM, Edwards JC. Circulating levels of B lymphocyte stimulator in patients with rheumatoid arthritis following rituximab treatment: relationships with B cell depletion, circulating antibodies, and clinical relapse. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:723–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gross JA, Dillon SR, Mudri S, Johnston J, Littau A, Roque R, et al. TACI‐Ig neutralizes molecules critical for B cell development and autoimmune disease: impaired B cell maturation in mice lacking BLyS. Immunity 2001;15:289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dall'Era M, Chakravarty E, Wallace D, Genovese M, Weisman M, Kavanaugh A, et al, and the Merck Serono and ZymoGenetics Atacicept Study Group. Reduced B lymphocyte and immunoglobulin levels after atacicept treatment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a multicenter, phase Ib, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, dose‐escalating trial. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:4142–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weinblatt M, Schiff M, Goldman A, Kremer J, Luggen M, Li T, et al. Selective costimulation modulation using abatacept in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis while receiving etanercept: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:228–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Genovese MC, Kinnman N, de La Bourdonnaye G, Pena Rossi C, Tak PP. Atacicept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy: results of a phase II, randomized, placebo‐controlled, dose‐finding trial. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:1793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prevoo ML, van 't Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty‐eight–joint counts: development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:44–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C, et al. American College of Rheumatology preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tak PP, Thurlings RM, Rossier C, Nestorov I, Dimic A, Mircetic V, et al. Atacicept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results of a multicenter, phase Ib, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, dose‐escalating, single‐ and repeated‐dose study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van Vollenhoven RF, Kinnman N, Vincent E, Wax S, Bathon J. Atacicept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase II, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:1782–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clifford DB, Ances B, Costello C, Rosen‐Schmidt S, Andersson M, Parks D, et al. Rituximab‐associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol 2011;68:1156–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rubbert‐Roth A, Tak PP, Zerbini C, Tremblay JL, Carreno L, Armstrong G, et al. Efficacy and safety of various repeat treatment dosing regimens of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a phase III randomized study (MIRROR). Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1683–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Emery P, Deodhar A, Rigby WF, Isaacs JD, Combe B, Racewicz AJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of different doses and retreatment of rituximab: a randomised, placebo‐controlled trial in patients who are biological naive with active rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate (Study Evaluating Rituximab's Efficacy in MTX iNadequate rEsponders (SERENE)) [published erratum appears in Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1519]. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1629–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Seyler TM, Park YW, Takemura S, Bram RJ, Kurtin PJ, Goronzy JJ, et al. BLyS and APRIL in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3083–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. C‐reactive protein (CRP) levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) in patients treated with 1,000 mg rituximab followed by once‐weekly 150 mg atacicept or placebo

Supplementary Table 2. Levels of Ig–rheumatoid factor in patients treated with 1,000 mg rituximab followed by once‐weekly 150 mg atacicept or placebo.