Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the effect of multifaceted interventions using the Achievable Benchmark of Care (ABC) method for improving the technical quality of diabetes care in primary care settings.

Methods

We conducted a 1‐year cluster randomized controlled trial in 22 regions divided into an intervention group (IG) or control group (CG). Physicians in the IG received a monthly report of their care quality, with the top 10% quality of diabetes care scores for all physicians being the achievable benchmark. The change in quality‐of‐care scores between the IG and CG during follow‐up was analysed using a generalized linear model considering clustering.

Results

A total of 2199 patients were included. Their mean (sd) age was 56.5 ± 5.9 years and the mean (sd) HbA1c level was 56.4 ± 13.3 mmol/mol (7.4 ± 1.2%). The quality‐of‐care score in the CG changed from 50.2%‐point at baseline to 51%‐point at 12 months, whereas the IG score changed from 49.9%‐point to 69.6%‐point, with statistically significant differences between the two groups during follow‐up [the effect of intervention was 19.0%‐point (95% confidence interval 16.7%‐ to 21.3%‐point; P < 0.001)].

Conclusions

Multifaceted intervention, measuring quality‐of‐care indicators and providing feedback regarding the quality of diabetes care to physicians with ABC, was effective for improving the technical quality of care in patients with Type 2 diabetes in primary care settings. (Trial Registration: umin.ac.jp/ctr as UMIN000002186)

What's new?

The effect of the Achievable Benchmark of Care (ABC) method in improving the quality of care has not been extensively studied in the field of diabetes care.

We evaluated the effect of multifaceted interventions using the ABC method to improve the technical quality of diabetes care in a prospective, cluster randomized controlled trial in primary care settings in Japan.

This study provided information on the strategies for improving the technical quality of diabetes care in primary care settings.

What's new?

The effect of the Achievable Benchmark of Care (ABC) method in improving the quality of care has not been extensively studied in the field of diabetes care.

We evaluated the effect of multifaceted interventions using the ABC method to improve the technical quality of diabetes care in a prospective, cluster randomized controlled trial in primary care settings in Japan.

This study provided information on the strategies for improving the technical quality of diabetes care in primary care settings.

Introduction

The incidence of Type 2 diabetes is increasing rapidly worldwide 1. A national survey in Japan from 1997 to 2007 showed that the number of patients with probable diabetes increased from 6.9 million to 8.9 million, whereas the number of patients with probable impaired glucose tolerance increased from 6.8 million to 13.2 million 2.

Practical guidelines for patients with diabetes have been developed by many organizations and are associated with better outcomes with regard to blindness, end‐stage renal disease, coronary artery disease, amputations and death 3, 4. Despite some improvements 5, the quality of diabetes care has not yet reached the level recommended by the practical guidelines developed on the basis of state‐of‐the‐art scientific evidence (‘evidence–practice gap’) 6, although the gap is gradually decreasing 5, 7. To reduce the ‘evidence–practice gap’ in diabetes care, effective, evidence‐based interventions should be developed. Improvements in the quality of diabetes care have previously been reported using multifaceted interventions in primary care settings 8, 9. Most of these studies, however, were poorly controlled, small and focused only on glycaemic control 8; few studies have focused on the technical quality of care. Donabedian 10 defined three quality components: technical quality of care, interpersonal quality of care and amenities. Technical quality of care is the extent to which the use of healthcare services meets predefined standards of acceptable or adequate care relative to the requirement (i.e. the patient received the recommended care). Interpersonal quality refers to the interaction between the provider and the patient.

The Achievable Benchmark of Care (ABC) method for improving healthcare quality, which has been used for quality control in industry since the 1980s, is being refined under an Agency for Health Care Policy and Research initiative 11. The achievable benchmark is determined on the performance basis of all members of a peer group and represents a realistic standard of excellence attained by the top performers in that group. The ABC method is objective, readily understandable, easily updated and useful for identifying areas that require improvements in the various fields 12, 13, 14. In a cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) in primary care settings, the ABC method has been shown to significantly improve the effect of physician performance feedback in a multifaceted, quality improvement intervention 15. However, the effect of the ABC method in improving the quality of care has not been extensively studied in the field of diabetes care.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of multifaceted interventions using the ABC method to improve the technical quality of diabetes care using a prospective, cluster RCT in primary care settings.

Patients and methods

Study design

This study was a 1‐year, prospective, cluster randomized, two‐armed intervention study. Details on the participants and methods have been reported elsewhere (Trial Registration: umin.ac.jp/ctr as UMIN000002186) 16. Briefly, 11 district medical associations (DMAs) were divided into two subregions (clusters) and then randomized to either the intervention group (IG) or the control group (CG). Each group acted as a cluster within the DMA. In the IG, patients received reminders for medical visits to their primary care physician (PCP) and lifestyle advice by telephone or face‐to‐face. In the CG, PCPs provided ordinary medical treatment to their patients. With a 1‐year intervention and follow‐up period, the primary outcome corresponding to the rate of patient drop‐out from regular medical care was evaluated. In this analysis, we focused on the quality of care, which is the secondary outcome of the original trial. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Japan Foundation for the Promotion of International Medical Research Cooperation.

DMAs and PCPs

The DMA eligibility criteria were as follows: participation of ~ 20 PCPs; ability to divide PCPs into two groups according to the geographical locations of their clinics and the DMA branch to which they belong, with an anticipated registration of 125 diabetes patients within each DMA group; capability of the DMA to establish a diabetes treatment network comprising PCPs, physicians specializing in diabetes and kidney disease, and ophthalmologists. The eligibility criteria for PCPs were as follows: membership of a recruited DMA; working as a PCP, not a board‐certified diabetologist; ability to acquire the consent of 10 or more patients with diabetes and no history of participation in a study with similar interventions within the last 5 years. Of the 15 municipal‐level DMAs eligible for this study, 192 PCPs at 11 DMAs met the inclusion criteria and provided consent to participate in the study. All DMAs were in urban areas with a median population of 174 462 (range, 34 243–966 493). All PCPs were solo practitioners and non‐diabetologists (mean age ± sd, 55.5 ± 8.4 years).

Patients

The patient eligibility criteria were as follows: diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes prior to registration, aged 40–64 years, no history of haemodialysis, no hospitalization, no bed confinement, not resident in a nursing home, no blindness, no history of lower limb amputation, no history of diagnosis with a malignant tumour within the last 5 years, no pregnancy or potential pregnancy, and care provided by a single medical doctor in charge of the patient's diabetes treatment (except in the event of diabetes complications). There was no inclusion restriction based on plasma glucose or HbA1c levels. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Randomization

Each municipal DMA was divided into two subregions (clusters). To split each DMA, a straight line was drawn on the map of the municipal areas to which each DMA belonged and the line adjusted if a PCP clinic was exactly on the line. The statistician, blind to the identities of the clusters, randomly allocated 0 (control) or 1 (intervention) codes generated by statistical software, to 22 clusters stratified by each DMA.

Data collection

Clinical research coordinators (CRCs) visited the PCP clinics on a regular basis and collected patients’ anonymous medical records. In the IG, the CRCs visited each clinic at 1, 4, 7, 10 and 13 months after the beginning of the follow‐up term. In the CG, the CRCs visited each clinic at 1 and 13 months after the beginning of the follow‐up term. Patients in both groups were asked to complete a self‐administered Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) survey questionnaire 17 at baseline. At baseline and during follow‐ups, CRCs visited the PCP clinics and collected blood pressure and laboratory data, including HbA1c levels, lipid profiles and urinary microalbumin levels. In addition, CRCs reviewed medical charts to determine whether patients received fundoscopic examination, foot examination or smoking cessation advice if they were smokers. For data collection, CRCs used pre‐specified care report forms. For the IG, CRCs visited the PCP clinics every 3 months, whereas in the CG, CRCs visited the PCP clinics only at baseline and at the end of the study. These data were used to evaluate the quality of diabetes care.

Outcome measures

For this analysis, we used a quality of diabetes care score calculated on the outcomes of eight quality indicators. The clinical information required to evaluate the outcome measures were gathered from medical charts. The eight clinical quality indicators were selected from those used in the Diabetes Quality Improvement Project 18 and were further revised based upon consideration of updated evidence and the Japan Diabetes Society clinical practice guidelines using a modified Delphi method 19. In a modified Delphi approach, a panel of experts assesses the appropriateness of particular clinical decisions in an iterative way. Initially, a literature study is carried out to critically appraise and summarize the evidence from clinical studies. Using the results from this overview and additional comments from the experts, quality indicators are selected that may be relevant for the clinical decision under investigation. A panel of experts is then asked to rate the appropriateness of certain clinical decisions for each of these indicators. A decision is called ‘appropriate’ when the expected benefit (e.g. symptom reduction) exceeds the expected risk (e.g. adverse event). The extent of appropriateness is expressed using a 9‐point scale in which 9 = extremely appropriate, 1 = extremely inappropriate and 5 = equivocal or uncertain. After the panellists have individually rated all indications, they meet to discuss the results. After this discussion, a second individual rating round takes place, in which all or part of the indications are rated a second time. Based on the median score and the extent of agreement for each of the quality indicators, a panel statement (appropriate, uncertain and inappropriate) is calculated. We used eight quality indicators that a panel finally rated as appropriate. The eight clinical indicators are shown in Table 1. Outcome differences may be due to case mix, how the data were collected, or quality of care. The advantages of process indicators are that they are more sensitive to quality of care differences and are a direct measure of quality. Thus, we focused mainly on the process of diabetes care. In addition, we evaluated the effect of intervention on patient outcomes comprising HbA1c, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and BMI.

Table 1.

Diabetes care quality indicators

| No. | Quality indicator |

|---|---|

| 1. | All patients with diabetes should have a medical check‐up at least every 3 months. |

| 2. | For all patients with diabetes, the HbA1c level should be examined at least every 3 months. |

| 3. | For all patients with diabetes, serum lipid levels should be examined at least every 12 months. |

| 4. | For all patients with diabetes, blood pressure should be checked during each visit to the clinic. |

| 5. | For all patients with diabetes, a fundoscopy should be performed at least every 12 months. |

| 6. | For all patients with diabetes, the patient's feet should be examined at least every 12 months. |

| 7. | For all patients with diabetes without overt proteinuria, urinary microalbumin levels should be examined at least every 6 months. |

| 8. | For all patients with diabetes who smoke, smoking cessation should be recommended at least every 12 months. |

Intervention

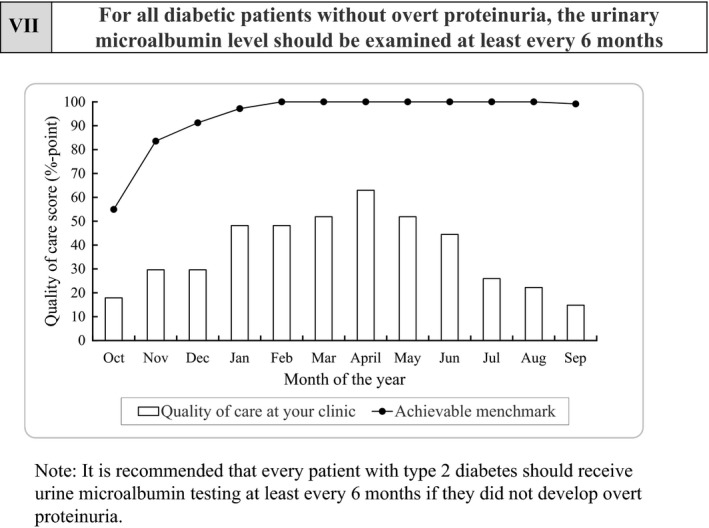

Physicians assigned to the IG were able to use a disease management system of monitoring and provided feedback on the quality of diabetes care, which was evaluated in terms of adherence to the eight clinical indicators. We prepared feedback sheets for adherence to these eight indicators using data from the physicians’ self‐report forms, as the physicians monitored and promoted these indicators to improve adherence (Fig. 1). Forms were sent by facsimile to the data centre every month. PCPs in the IG received a feedback letter every month that included their quality of diabetes care score and the benchmarks for each indicator calculated as the average top 10% of PCP indicators every month as achievable goals.

Figure 1.

An example of the feedback sheet used to evaluate the quality‐of‐care score for the participating physicians. This sheet shows the quality‐of‐care score for indicator 7 (urinary microalbumin testing). The bar graph indicates the quality‐of‐care score at the clinic where this sheet was sent, and the line graph indicates the achievable benchmark for this indicator representing the monthly average top 10% score for the participating physicians, regarded as achievable goals.

Other intervention components included reminders for regular visits and lifestyle modifications. The study group established a Treatment Support Centre that sent reminders to the patients for regular medical visits to their PCPs and provided lifestyle modification interventions aimed to encourage behavioural changes in terms of diet and exercise. The PCPs filled out the pre‐specified instruction form for each patient with respect to target body weight, recommended food intake and permission or notandum for exercise therapy and sent it to the Treatment Support Centre. The centre then offered the information written in this form to certified diabetes educators, registered dieticians or public health nurses who participated in the standardized programme for behavioural theory on patient education. They then provided advice by telephone based on this instruction form. Patients were supposed to receive six sessions of phone calls on lifestyle advice each lasting ~ 15–30 min. However, in some DMAs that trained certified diabetes educators and provided a location for face‐to‐face advice, four sessions of face‐to‐face advice were provided for ~ 30 min each. All interventions lasted for 1 year.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics between the intervention and control groups were calculated using proportions and means with standard deviations. Because randomization was at the cluster level, patient‐level characteristics would not be as likely to balance out as random at the patient level. Covariate balance was checked using fixed effects linear regression for continuous confounders (e.g. age) and fixed effects binomial or multinomial logistic regression for categorical confounders (e.g. gender) considering clustering within each DMA.

First, adherence to the clinical indicators was calculated for PCPs as the percentage of recommended care processes received, referred to as the quality‐of‐care score (%‐point); we used the equation shown in the Appendix and each indicator had the same weight. To evaluate the effects of intervention on the change in adherence to quality indicators, we subtracted the baseline score from the score at the end of the study to calculate the change in score during the follow‐up. Further, we examined the relationship between the change in the quality‐of‐care score and the intervention using a generalized linear model that considered clustering within the unit of randomization. We first performed this analysis for all indicators and then for each indicator.

To next evaluate the effect of modification of patient‐level factors on the effect of intervention for improving the quality of diabetes care, we used logistic regression analysis with adherence to each indicator (1 = adherent, 0 = non‐adherent) as an outcome.

For patient's outcomes, we calculated the difference of each outcome subtracting the value at baseline from that at 12 months and used linear regression analysis considering clustering within each DMA adjusted for baseline value. All analyses were performed using Stata/SE 12.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

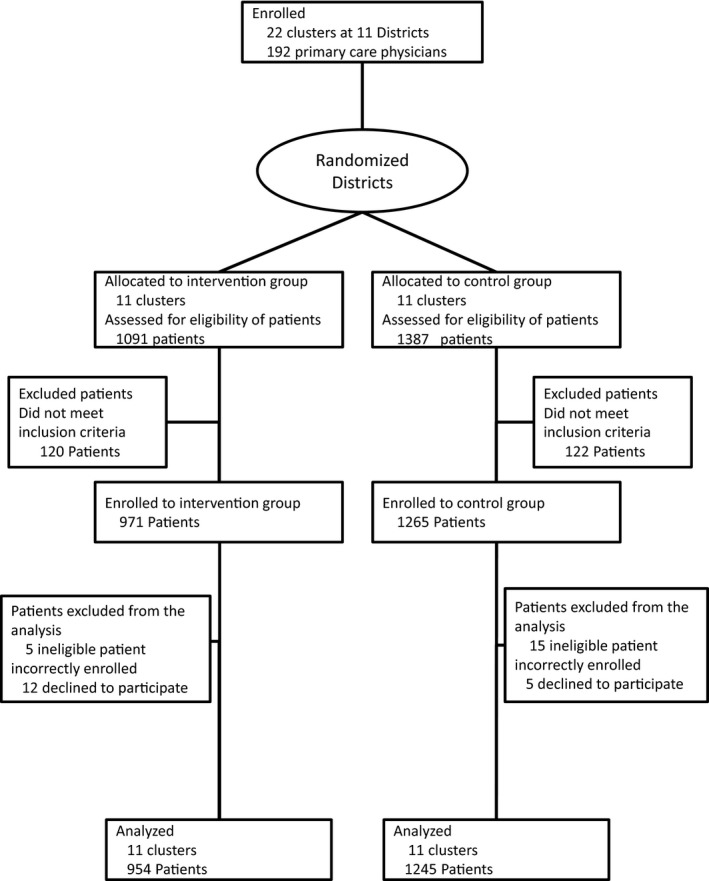

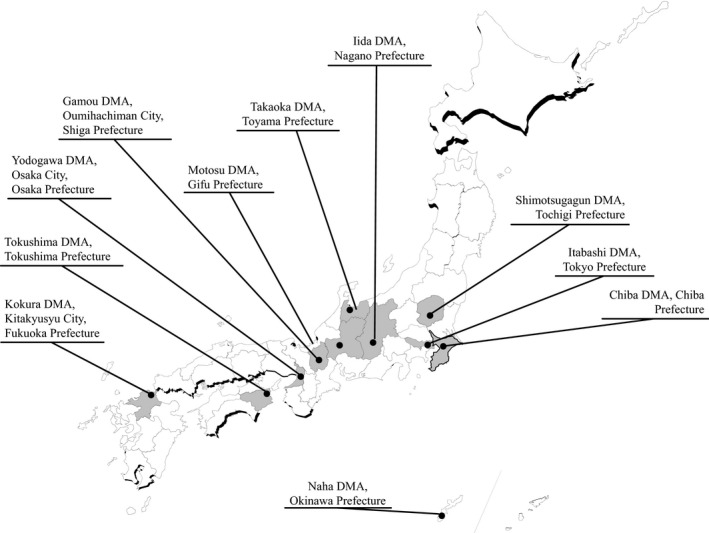

Figure 2 shows the flow of study clusters and the patients eligible for this trial. Of the 15 DMAs screened, 11 (22 clusters) were eligible for this trial and randomized into intervention and control groups stratified by each DMA (Fig. 3). A total of 1091 patients in the IG and 1387 patients in the CG were assessed for eligibility. Of these patients, 971 patients were enrolled in the IG and 1265 in the CG. All 22 clusters were followed until the end of the trial. For the final analysis, 954 patients were enrolled in the IG and 1245 patients in the CG after excluding patients who proved to be ineligible or who declined to participate at a later stage. The patients’ baseline characteristics are shown in Table 2. The mean age was 56.5 ± 5.9 years and 37.5% were women. The mean HbA1c level was 56.4 ± 13.3 mmol/mol (7.4 ± 1.2%). There was no statistical difference in baseline characteristics other than the type of diabetes therapy between the IG and the CG; patients in the IG were more likely to receive diabetes medication (P = 0.049).

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow chart illustrating the recruitment of patients for the present randomized controlled trial.

Figure 3.

Geographical presentation of the 11 district medical associations (DMAs). Map of Japan describing the participating DMAs ( ). Solid lines on the map indicate prefecture borders.

). Solid lines on the map indicate prefecture borders.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants according to the assigned interventiona

| All | Control | Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | n = 2199 | n = 1245 | n = 954 | P |

| Primary care clinics | n = 192 | n = 99 | n = 93 | |

| Age, years | 56.5 (5.9) | 56.5 (5.9) | 56.5 (5.9) | 0.961 |

| Female, % | 37.5 | 36.2 | 39.1 | 0.102 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.0 (4.2) | 26.0 (4.1) | 25.9 (4.3) | 0.525 |

| HbA1c | ||||

| IFCC, mmol/mol | 56.4 (13.3) | 56.0 (13.0) | 56.9 (13.7) | |

| NGSP, % | 7.4 (1.2) | 7.3 (1.2) | 7.4 (1.3) | 0.304 |

| Diabetes therapy, % | 0.048 | |||

| No medication | 10.6 | 12.0 | 8.9 | |

| Oral hypoglycaemic agent only | 81.2 | 80.1 | 82.6 | |

| Insulin | 8.2 | 7.9 | 8.5 | |

| PAID | 36.0 (13.1) | 36.5 (13.4) | 35.2 (12.7) | 0.134 |

Data are presented as mean (sd).

IFCC, International Federation of Clinical Chemistry; NGSP, National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program; PAID, Problem Areas in Diabetes scale score.

The effect of intervention on the quality‐of‐care score for PCPs is shown in Table 3. Overall, the quality‐of‐care score for all participants was 50.1%‐point [95% confidence interval (CI) 48.7%‐ to 51.5%‐point] at baseline. The score did not significantly improve in the CG from 50.2%‐point (95% CI 48.2%‐ to 52.3%‐point) at baseline to 51.0%‐point (95% CI 38.3%‐ to 71.4%‐point) at 12 months. However, in the IG it did improve from 49.9%‐point (95% CI 48.2%‐ to 51.7%‐point) at baseline to 69.6%‐point (95% CI 49.5%‐ to 95.2%‐point) at 12 months. We observed statistically significant changes in the score during follow‐ups between the two groups and the mean effect of intervention was 19.0%‐point (95% CI 16.7%‐ to 21.3%‐point; P < 0.001). Next, we observed the effect of intervention on the quality‐of‐care score for each indicator. The quality‐of‐care scores at baseline for indicators 1, 2 and 3 were very high at 92.4%‐point (95% CI 65.0%‐ to 100%‐point), 82.1% (95% CI 40.0%‐ to 100%‐point) and 85.4%‐point (95% CI 45.5%‐ to 100%‐point) respectively. The score for indicator 4 was moderate at 67.0%‐point (95% CI 22.2%‐ to 100%‐point), whereas scores for indicators 5–8 were very low from 6.1%‐ to 16.4%‐point. We observed statistically significant differences between the two intervention groups in terms of a change in the quality‐of‐care scores for indicators 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 during follow‐ups4. The effect of intervention on patient outcomes is shown in Table 4. We observed statistically significant change in HbA1c by −1.49 mmol/mol (95%CI −2.76 to −0.21 mmol/mol), and BMI by −0.21 kg/m2 (95%CI −0.33 to −0.98).

Table 3.

The effect of intervention on adherence to quality indicators in primary care clinics

| Baseline | 12 months | Effects of intervention | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | ||||

| Participants | n = 1245 | n = 954 | |||||

| Primary care clinics | n = 99 | n = 93 | n = 99 | n = 93 | |||

| Overall quality‐of‐care score, %‐point (95% CI) | 50.2 (48.2 to 52.3) | 49.9 (48.2 to 51.7) | 51.0 (38.3 to 71.4) | 69.6 (49.5 to 95.2) | 19.0 (16.7 to 21.3) | < 0.001 | |

| Quality‐of‐care score for each indicator, %‐point (95% CI) | |||||||

| 1 | All patients with diabetes should have a medical check‐up at least every 3 months | 92.1 (47.6 to 100) | 92.7 (75.0 to 100) | 94.7 (81.0 to 100) | 98.7 (92.7 to 100) | 3.4 (–2.0 to 8.9) | 0.195 |

| 2 | For all patients with diabetes, the HbA1c level should be examined at least every 3 months | 80.9 (33.3 to 100) | 83.4 (50.0 to 100) | 80.9 (40.0 to 100) | 93.5 (62.5 to 100) | 10.2 (6.1 to 14.2) | < 0.001 |

| 3 | For all patients with diabetes, the serum lipid level should be examined at least every 12 months | 86.7 (45.5 to 100) | 84.1 (50.0 to 100) | 90.1 (50.0 to 100) | 94.0 (58.3 to 100) | 6.6 (–1.0 to 14.1) | 0.08 |

| 4 | For all patients with diabetes, blood pressure should be checked at each visit to the clinic | 65.2 (22.2 to 100) | 69.4 (20.0 to 100) | 67.1 (25.0 to 100) | 80.8 (40.7 to 100) | 9.5 (4.4 to 14.5) | 0.002 |

| 5 | For all patients with diabetes, a fundoscopy should be performed at least every 12 months | 12.4 (0 to 50) | 13.9 (0 to 57.1) | 11.1 (0 to 50.0) | 45.0 (0 to 100) | 32.4 (25.6 to 39.1) | < 0.001 |

| 6 | For all patients with diabetes, the patient's feet should be examined at least every 12 months | 20.2 (0 to 86.7) | 12.3 (0 to 50.0) | 18.7 (0 to 100) | 55.0 (0 to 100) | 44.2 (35.5 to 52.9) | < 0.001 |

| 7 | For all patients with diabetes without overt proteinuria, the urinary microalbumin level should be examined at least every 6 months | 6.7 (0 to 45.8) | 5.6 (0 to 45.8) | 8.0 (0 to 66.7) | 24.6 (0 to 100) | 17.8 (11.5 to 24.1) | < 0.001 |

| 8 | For all patients with diabetes who smoke, smoking cessation advice should be provided at least every 12 months | 11.8 (0 to 60.0) | 9.7 (0 to 50.0) | 10.3 (0 to 50.0) | 48.5 (0 to 100) | 40.4 (29.0 to 51.7) | < 0.001 |

Table 4.

The effect of intervention on patient outcomes

| Outcomes | Difference: 12 months–baseline (control group)a | Difference: 12 months–baseline (intervention group)a | Difference: Intervention–control (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | 0.027 | |||

| ICFF, mmol/mol | −0.98 (10.5) | −2.79 (10.6) | −1.49 (−2.76 to −0.21) | |

| NGSP, % | −0.09 (0.97) | −0.26 (0.98) | −0.14 (−0.26 to −0.02) | |

| SBP, mmHg | 0.69 (14.88) | −0.82 (13.6) | −1.58 (−3.33 to 0.17) | 0.072 |

| DBP, mmHg | −0.64 (9.4) | −0.50 (9.0) | −0.60 (−1.61 to 0.41) | 0.213 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.05 (0.98) | −0.16 (1.2) | −0.21 (−0.33 to −0.98) | 0.002 |

Mean and sd.

Discussion

This large‐scale, cluster randomized controlled study has shown that multifaceted interventions measured by quality‐of‐care indicators and feedback regarding the quality of diabetes care with ABC to physicians were effective in improving the technical quality of care for patients with Type 2 diabetes in primary care settings.

To our knowledge, this is the first large‐scale, cluster randomized study conducted in Japan to evaluate the effects of multifaceted interventions to improve the technical quality of diabetes care. Our study has several strengths. First, this is a multi‐institutional study in which PCPs from different areas of Japan participated; therefore, our results can be applied to actual clinical settings in Japan. Second, this was a large‐scale, well‐designed study that adapted a cluster randomized design. The unit of randomization is a key issue in trial design to evaluate quality improvement interventions. In addition, contamination, which occurs because physicians or patients within distinct areas share information regarding the intervention or because clinics do not adhere to their assigned intervention if the unit of randomization, a physician or a patient, introduces bias 20. The J‐DOIT 2 is one of three research strategies supported by a national fund of ¥4 billion from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) in Japan to fight Type 2 diabetes and obesity 21. Although cluster randomized trials are more difficult to design compared with individually randomized trials for several reasons 20, Japanese government initiatives permitted us to conduct this complex, well‐designed, randomized controlled trial.

Among all indicators, our intervention was not effective in improving the quality‐of‐care score as assessed at the 3‐month follow‐ups (indicator 1). Given that the baseline quality‐of‐care score for this indicator was very high at 92.4%‐point, it should be further improved for adherence to this indicator. Similarly, our intervention was not statistically significant in terms of improving the quality‐of‐care score for annual lipid testing (indicator 3). The adherence to renal screening at baseline was very low (6.1%‐point) probably because the health insurance system in Japan only permits urine albumin testing every 4 months. Similarly, the quality‐of‐care score for foot examination was very low compared with that reported in a meta‐analysis (median of included studies, 47%‐point) 22. In Japan, the mean consultation time for patient visits is only 6.16 min 23, therefore, physicians do not have enough time to examine patients’ feet. Despite this difficult situation for physicians in Japan, our intervention improved the quality‐of‐care score for the above indicators with very low adherence.

Our study has shown that our multifaceted intervention was significantly effective in promoting smoking cessation in patients with diabetes. Studies of diabetes patients have consistently demonstrated that smokers have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, premature death and an increased rate of microvascular diabetic complications. Therefore, promotion of smoking cessation is a key component for diabetes care 24. However, in a published meta‐analysis that evaluated the effect of quality improvement strategies for diabetes care, the pooled effect of the intervention to promote smoking cessation was not statistically significant 22. We suggest several reasons for our success in promoting smoking cessation in patients with diabetes. First, our intervention included the ABC method, which may promote competition among physicians and change their behaviour in terms of providing smoking cessation advice resulting in the increased rate of smoking cessation in the IG. Second, it was suggested in a meta‐analysis that the quality improvement intervention was more effective if the study enrolled patients who did not achieve diabetes‐relevant quality indicators 22. The smoking rate in Japan is very high (~ 44%) and needs to be decreased; this situation may promote our intervention.

It could be argued that the frequency of measuring quality indicators might have influenced the quality‐of‐care score; in the IG, CRCs visited the PCP clinics every 3 months, whereas in the CG, CRCs visited the PCP clinics only at baseline and at the end of the study. There is no evidence that a high measuring frequency is associated with better quality of care; individuals improve their behaviour in response to their awareness of being observed, a phenomenon known as the Hawthorne effect 25.

Over the past decade, the quality of diabetes care in the United States has improved 5. This might be related to the use of quality‐of‐care measures such as comparing provider performance or the use of performance incentives 26. In other areas in the world founded on the presumption that guideline‐based care will generate savings by reducing demands on costly hospital‐based services over the long‐term incentive programmes aimed at improving diabetes outcomes are increasing in popularity 27. The concept of measuring the effectiveness among diabetes care providers is not new. The United Kingdom (UK) is the most ambitious example of pay‐for‐performance in diabetes care. In connection with an initiative to improve chronic disease care and outcomes, the UK government introduced a pay‐for‐performance model called the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF) as part of the general practitioner contract in 2004. The evidence suggests that in the UK, incentive models have spurred some improvements in process outcomes 28, 29. However, these improvements do not appear to have been uniform across all patients groups 30. In 1999, Australia introduced financial incentives to PCPs related to the quality of care for patients with chronic diseases in the form of the Practice Incentive Programme 31. Under the Practice Incentive Programme, PCPs can elect to participate in a blended payment model, which includes additional incentives for each patient who completes a cycle of care, including diabetes mellitus. In 2001, Taiwan introduced a voluntary incentive programme (DM‐P4P) for diabetes care. The Taiwan National Health Insurance design initially involved care management fees provided to physicians for achieving process‐based outcomes 32. In Canada, several provinces have introduced incentive programmes in the form of enhanced billing or condition‐based payments. Physicians can receive additional payments for each patient with diabetes who is managed in accordance with practice guidelines 33.

This carefully designed, large‐scale, randomized controlled study has several limitations. Because our study was conducted in Japan, which has adopted a public health insurance system for the entire nation, our results may not be applicable to countries with different organizational or insurance systems. Moreover, the contribution of individual components of our intervention was not evaluated, but this weakness is present in the evaluation of all multifaceted interventions.

In conclusion, multifaceted interventions, by measuring quality‐of‐care indicators and providing feedback to physicians regarding the quality of care with ABC were effective in improving the technical quality of care in patients with Type 2 diabetes in primary care settings, thereby offering promising strategies for improving technical quality of care in primary care settings.

Funding sources

Funding was received from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, Grant Number: Practical Research Project for Life‐Style related Diseases including CVD and Diabetes; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, Grant Number: Strategic Outcomes Research Program for Research on Diabetes; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, Grant Number: Comprehensive Research on Life‐Style Related Diseases including CVD and Diabetes H25‐016. The funding source had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, report writing or decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests

None declared.

Yi: quality‐of‐care score.

i: identification number of participant.

j: identification number of the eight quality indicators, j = 1, 2, …, 8.

Xd ij: Xd ij = 1 if the physician adhered to the jth indicator for participant I; Xd ij = 0 if the physician did not adhere to the jth indicator for participant i.

Xn ij: Xn ij = 1 if the jth indicator was applicable to participant i; Xn ij = 0 if the jth indicator was not applicable to participant i.

Diabet. Med. 33, 599–608 (2016)

References

- 1. International Diabetes Federation . IDF Diabetes Atlas update poster, 6th edn Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . National Health and Nutrition Survey, Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes–2015: summary of revisions. Diabetes Care 2015; 38(Suppl S4): doi: 10.2337/dc15‐S003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Global Guideline for Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014; 104: 1–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saaddine JB, Cowie CC, Imperatore G, Gregg EW. Achievement of goals in U.S. diabetes care, 1999–2010. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1613–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saaddine JB, Cadwell B, Gregg EW, Engelgau MM, Vinicor F, Imperatore G et al Improvements in diabetes processes of care and intermediate outcomes: United States, 1988–2002. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 465–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stone MA, Charpentier G, Doggen K, Kuss O, Lindblad U, Kellner C et al Quality of care of people with type 2 diabetes in eight European countries: findings from the Guideline Adherence to Enhance Care (GUIDANCE) study. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 2628–2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin SJ, Wagner EH, Eijk Van JT, Assendelft WJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes in primary care, outpatient, and community settings: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 1821–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Majumdar SR, Guirguis LM, Toth EL, Lewanczuk RZ, Lee TK, Johnson JA. Controlled trial of a multifaceted intervention for improving quality of care for rural patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 3061–3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA 1988; 260: 1743–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clancy CM. Ensuring health care quality: an AHCPR perspective. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Clin Ther 1997; 19: 1564–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hall RE, Khan F, Bayley MT, Asllani E, Lindsay P, Hill MD et al Benchmarks for acute stroke care delivery. Int J Qual Health Care 2013; 25: 710–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hammermeister K, Bronsert M, Henderson WG, Coombs L, Hosokawa P, Brandt E et al Risk‐adjusted comparison of blood pressure and low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) noncontrol in primary care offices. J Am Board Fam Med 2013; 26: 658–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wadland WC, Holtrop JS, Weismantel D, Pathak PK, Fadel H, Powell J. Practice‐based referrals to a tobacco cessation quit line: assessing the impact of comparative feedback vs general reminders. Ann Fam Med 2007; 5: 135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kiefe CI, Allison JJ, Williams OD, Person SD, Weaver MT, Weissman NW. Improving quality improvement using achievable benchmarks for physician feedback: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 285: 2871–2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Izumi K, Hayashino Y, Yamazaki K, Suzuki H, Ishizuka N, Kobayashi M et al Multifaceted intervention to promote the regular visiting of patients with diabetes to primary care physicians: rationale, design and conduct of a cluster‐randomized controlled trial. The Japan Diabetes Outcome Intervention Trial‐2 study protocol. Diabetol Int 2010; 1: 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, Welch G, Jacobson AM, Aponte JE et al Assessment of diabetes‐related distress. Diabetes Care 1995; 18: 754–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fleming BB, Greenfield S, Engelgau MM, Pogach LM, Clauser SB, Parrott MA. The Diabetes Quality Improvement Project: moving science into health policy to gain an edge on the diabetes epidemic. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 1815–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, Kessels AG, Boers M, Bouter LM et al The Delphi list: a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51: 1235–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Glynn RJ, Brookhart MA, Stedman M, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Design of cluster‐randomized trials of quality improvement interventions aimed at medical care providers. Med Care 2007; 45(10 Suppl 2): S38–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T. Combating diabetes and obesity in Japan. Nat Med 2006; 12: 73–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tricco AC, Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, Moher D, Turner L, Galipeau J et al Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies on the management of diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet 2012; 379: 2252–2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wooldridge AN, Arató N, Sen A, Amenomori M, Fetters MD. Truth or fallacy? Three hour wait for three minutes with the doctor: findings from a private clinic in rural Japan. Asia Pac Fam Med 2010; 9: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. American Diabetes Association . Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes–2013. Diabetes Care 2013; 36(Suppl 1): S11–S66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P. The Hawthorne effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007; 7: 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pogach L, Aron DC. Sudden acceleration of diabetes quality measures. JAMA 2011; 305: 709–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Latham LP, Marshall EG. Performance‐based financial incentives for diabetes care: an effective strategy? Can J Diabetes 2015; 39: 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Calvert M, Shankar A, McManus RJ, Lester H, Freemantle N. Effect of the quality and outcomes framework on diabetes care in the United Kingdom: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2009; 338: b1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alshamsan R, Lee JT, Majeed A, Netuveli G, Millett C. Effect of a UK pay‐for‐performance program on ethnic disparities in diabetes outcomes: interrupted time series analysis. Ann Fam Med 2012; 10: 228–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alshamsan R, Millett C, Majeed A, Khunti K. Has pay for performance improved the management of diabetes in the United Kingdom? Prim Care Diabetes 2010; 4: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Russell G, Mitchell G. Primary care reform. View from Australia. Can Fam Physician 2002; 48: 440–443, 9–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheng SH, Lee TT, Chen CC. A longitudinal examination of a pay‐for‐performance program for diabetes care: evidence from a natural experiment. Med Care 2012; 50: 109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Canadian Diabetes Association, Diabète Québec . Diabetes: Canada at the Tipping Point – Charting a New Path. Toronto: Canadian Diabetes Association, 2010. [Google Scholar]