Introduction

As family members age, there are often concerns about housing and living arrangements. If older adults plan to stay in their current homes, there may be a need for support in the form of home modification. Other older individuals and couples may choose not to age in place. Concerns about their emotional well-being, physical health, and safety may lead them to consider relocation. Relocation as an older couple requires discussion and decision-making about the future as it has an important impact on each member of the dyad. The decision to relocate can be supported or even strongly encouraged by kin (i.e. adult children, grandchildren or others in the kin network) as they express concern for the well-being of their older family members. Other kin may not support relocation, in light of their concerns regarding cost and quality of care. Caro et al. (2012) found that a greater likelihood that adult children would recommend moves than older persons themselves. However, other studies show that older adults make the decisions and adult children become involved by supporting the older adults in the relocation process (Knight & Buys, 2003; Strough, J., Neely, T., Snyder, K., Kimbler, K., & Margrett, J., 2004). The desire not to be a burden has been found to be one of the reasons older adults voluntarily relocate (Krout, Moen, Holmes, Oggins & Bowen, 2002; Jungers, 2010; Blinded for Review, 2014).

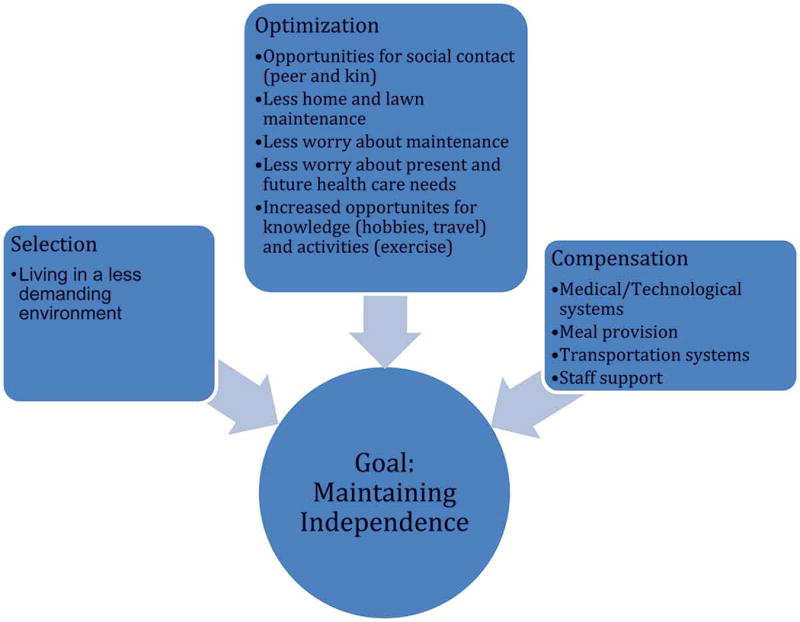

In many cases, moving is a family affair, suggesting that relocation affects more than the older adult who desires to voluntarily relocate. In this paper, we explore processes of relocation through Baltes and Baltes (1990) theoretical framework of Selection, Optimization with Compensation to show how “optimization” can be viewed interpersonally and in regards to the older adult’s available resources. By applying this framework beyond an individual’s strategic functioning, we present a decision-making application that highlights an understanding of how a family or kin network navigates housing concerns for older adults.

Background

Older adults may move to environments requiring less maintenance and worry. They may voluntarily relocate anticipating health and cognitive changes (Sherwood et al., 1997; Wiseman, 1980) or relocate in reaction to changes in their health. Relocation in older adulthood has been described in terms of amenity moves where older adults move to places desired to live, relocation near family and relocation live in places where medical assistance may be available if needed (Litwak and Longino, 1987). Recent studies have also examined the degrees of voluntariness of relocation, where relocation can be an individual and family decision or occur involuntarily in cases of natural disasters or gentrification (author, 2015). The process may involve planning for one’s future needs as well as considering and reconciling one’s previous histories of belonging and ownership of possession (Marcoux, 2001; Luborsky et al., 2012).

The voluntary relocation of older adults explored in this study can be examined in terms of strategic functioning. The SOC model proposes that older people often make strategic decisions about their lifestyles that they hope will result in more optimal functioning. Baltes and Baltes argue that in order to promote functioning, older persons select activities to concentrate on, which includes selecting against continuing other lifestyle activities (1990). These selections may result in optimized functioning for the older person that enriches his or her “general reserves” (Baltes & Baltes, 1990, p. 22). Often, this paring down of activities may be compensatory or adaptive, exhibiting behaviors that support the continuance of participation in the activities they have selected.

Selection

As people age, they will “select,” or determine, different domains to pursue to achieve their goals. Selection is critical to behavioral and developmental processes (Marsiske, Lang, Baltes, & Baltes, 1995). Without selection of certain domains or activities, an individual would not know where to direct his or her energy or resources. These may be individually and socially established aims (Marsiske et al., 1995).

Aging itself affects how the SOC model is applied to one’s life. Some scholars argue that with the onset of later adulthood, individuals aim to maintain their current functioning or independent lifestyle, or they may aim to prevent cognitive and physical losses rather than focus on achievement goals (Marsiske et al., 1995). Goals have also been conceptualized by some scholars in terms of “approach” or “avoidance” goals (Marsiske et al., 1995). In other words, “approach” goals orient a person toward attainment, something like learning a new hobby or developing better friendships. On the other hand, “avoidance goals” can be considered similar to prevention of losses, like maintaining mobility or health status. In addition, whether one frames a goal as a potential loss rather than as a potential gain affects the risks one is willing to take. Marsiske et al. (1995) argues that people are willing to take more risks when they attempt to counteract a loss.

Since the SOC model is framed as dynamic and includes an ongoing assessment of one’s choices, it should be considered within a “matrix of alternatives” (Marsiske et al., 1995, p. 41). When a previous choice no longer provides the intended benefit, or when the cost of a choice becomes greater than when first selected, new domains may be chosen. Importantly, Freund and Baltes (2000) suggest that “empirical studies need to address whether some goals might be subjectively so central for a person’s sense of leading a meaningful life that giving them up would lead to even stronger feelings of loss than continuing to engage in (fruitless) compensatory efforts” (p. 52).

Optimization

The second component of the model, optimization, addresses the path toward achieving a goal. In this path, scholars have noted a “pre-actional” phase where plans are made. To enact these plans, time and energy is required to enrich or at the very least, prevent depletion of one’s reserves. Sometimes, learning from others who have successfully coped with some age-related challenges, may lead one to follow their examples. In other words, persons learn by “modeling successful others” (Freund & Baltes, 2000, p. 46). Scholars also argue that having high self-efficacy beliefs affects this process (Freund & Baltes, 2000). Even if goals are chosen by an individual, their perception of how much they can control outcomes affects the optimization process.

Compensation

The third component of the SOC model, compensation, is often conceptualized as integrated with optimization. Some scholars distinguish between optimization and compensation in terms of growth or decline. Freund and Baltes argue, “whereas optimization is motivated by consideration of processes related to growth, compensation addresses the aspect of losses and decline” (2000, p. 49). However, this dichotomy is not always useful as the literature also indicates that the same actions can be considered either compensation or optimization. For example, Freund and Baltes (2000) give the example of practicing phonetic articulation. A child practicing phonetic articulation may be optimizing the goal of developing language skills, whereas these same actions undertaken by an older adult may be compensating for neurological challenges to counteract loss from a stroke (Freund & Baltes, 2000, p. 50).

Though compensation was originally thought to be related to decline, compensatory approaches should be considered the means to optimize one’s goals. In the original Baltes and Baltes (1990) article, they provided the example of the pianist Rubenstein. Rubenstein compensated for his declining agility by limiting his repertoire to optimize his performances.

Application of the SOC Model to the Relocation of Older Adults

To understand relocation of older adults through the lens of the SOC model, we adapt Baltes and Baltes’ phrase, “a less demanding physical and social ecology” (1990, p. 24) to “living in a less demanding environment.” In Baltes and Baltes’ (1990) text, the authors offer SOC examples. One example is Rubenstein’s strategy of reducing the number of pieces he plays (selection), practicing the pieces more often (optimization), and playing the pieces with reduced speed (compensation) while maintaining the contrast between slow and fast sections of the music. Another example is the selection of living in nursing homes, where increased social contact expands older adults’ social reserves (optimization) and systems of technological and medical help are available where needed (compensation).

Living in a Less Demanding Environment

The application of the SOC model to nursing homes can be extended today as older adults being able to choose a less demanding environment to live in (selection), which may lead to optimizing their lives in different ways. Optimization, according to Baltes and Baltes (1990), “reflects the view that people engage in behaviors to enrich and augment their general reserves” (p. 22). By selecting an environmental domain older adults can master, they enhance their reserves in multiple ways. They may also bring in compensations to sustain living in the new environment.

In selecting to live in a less demanding environment, an older adult may move to a one-level housing unit where carrying laundry up and down stairs is not a concern. This move also avoids the potential risks of falls and fractures, which entail decreased mobility and a long recovery process. As previously stated, Marsiske et al. (1995) argue that people are willing to take more risks to counteract a loss. In the case of moving, other associated risks may involve leaving one’s home in a neighborhood with long-established ties. While some older adults move locally or to locations near their original homes, some risk disrupting their existing social support networks by moving across the state or country or even farther to live near kin.

There are different ways older adults’ lives are optimized by living in a “less demanding” environment. Baltes and Baltes (1990) argue that in residential cohabitation of older adults, there is also opportunity for optimization by enriching their emotional reserves because there is opportunity for social contact with peers. There might also be opportunities for social contact with kin if older adults move near their kin, which scholars have found is a common moving practice of older adults (Litwak & Longino, 1987). Additional optimization possibilities include less need to use physical and emotional reserves. If they spend less physical energy on home and lawn maintenance, they will have fewer emotional worries about chores to perform at home. They will also have the opportunity to pursue knowledge and exercise, as they may have more time available due to decreased time needed for home maintenance. Also, there may be less worry about possessions, as material divestiture may have occurred during the move. Lastly, there may be less worry about future health care needs.

Medical and technological supports may also be available when older adults move to continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs) or other senior living facilities, as mentioned in the original Baltes and Baltes’ (1990) example of compensations available in nursing homes. With the advent of an array of long-term care options, other compensations may also be available if needed, including meals, staff support, and transportation. Today, meals can often be provided either in dining halls or through deliveries to individual units. Staff support may cover many things such as opportunities for social outings facilitated by staff members or emotional support in transitioning to the pace and culture of a new community. Transportation offered in older adults’ residential communities can compensate when older adults have stopped driving or have come to rely on family members for transportation. Transportation as a compensation may also facilitate increased social interactions (optimization) as some older adults may welcome outings with peers to cultural events and shopping. Transportation provided to medical appointments without having to rely on kin may also reduce worry about health care needs (optimization).

Goals may be created proactively or in response to losses (Freund & Baltes, 2002). In the case of selecting a less demanding living environment in order to achieve a goal of maintaining one’s independence, some older adults project possible physical and health limitations for themselves or their spouses even though they are well at the time of selection. Others will select living in a less demanding environment to achieve the goal of maintaining one’s independence as a reaction to the loss of a spouse, or to decreased physical functioning.

Application of the SOC Model to a Network

As kin are often key participants in relocation experiences of older adults, relocation itself can be considered a “social” process. Considering relocation in this way innovates on the SOC model because 1) it both expands upon Baltes and Baltes’ original idea of moving to a nursing home to also apply to a continuum of senior housing options and 2) applies the SOC model to dyadic relationships and to other members of a kin network. Unlike Baltes and Baltes’ original applications of the model to piano playing or running (Baltes & Baltes, 1990) and others’ applications of the model to driving cessation and hypothetical concerns of aging in place (Pickard, Tan, Morrow-Howell, & Jung, 2009, Kelly et al., 2014) relocation is unique because a couple may select it and undertake it together. But even given the potential for mutual selection, the way each member of the couple optimizes and compensates in the model may be unique. Other applications of the SOC model have looked at the way individuals utilizing SOC strategies within relationships can reduce stress at home or at work (Baltes & Heydens-Gahir, 2003; Young, Baltes & Pratt, 2007), but they have not directly applied the model to a dyad, however. Moving as a couple to a long-term care setting is unique among other compensatory decisions older adults may make. The couple selects a common goal as a dyad, although optimization and compensation for each individual may be different. Since older adults may not age as quickly as their partner, in many relationships one becomes the caregiver while the other receives care. (Lavela & Ather, 2010; Carpenter & Mak, 2007; Dixon, 2011). Moving to a CCRC may be a mutually beneficial selection for the couple in which each individual in the relationship has unique optimization and compensation adaptations.

In addition to couples, other members of a kin network, including adult children, are also affected by the older adult’s relocation. While living in a less demanding environment may mean more time for social contact with peers and kin, it may also complicate family members’ lives, who may need to alter schedules to accommodate the increased contact. For example, kin may hang pictures for older adults in the new environment, help with groceries and transport them to doctor visits. Another manner in which relocation affects the kin network involves the older adult’s capacity to adapt to the relocation. For instance, an older adult’s diminished cognitive ability may complicate the kin’s lives as there will be extra time and energy placed in assisting the older adult adjust (Author, blinded).

Methodology

The principal investigator (first author) employed a panel design, attempting to follow older persons and their family and friend through three stages of moving: 1) pre-move planning, 2) move in-process, and 3) post-move adjustment. Though not discrete, conceptually, the three stages served to distinguish those older adults who “completed” a move from those who were only engaged in the pre-move planning but did not undertake a move, and those were interviewed after their moves in their post-move adjustment phase.

Data were collected between January of 2009 and May 2012. The time frame reflects both the experiences of study participants who spent considerable time preparing before executing their moves, and the open-ended nature of post-move adjustment, which continues for many. The data collection phase also reflects an epistemological approach characteristic of anthropology, in which prolonged engagement allows the researcher time to build relationships and witness, as well as participate, in unfolding processes (Miles & Huberman, 1994, p. 6).

Study Sample

The principal investigator wanted to understand the moving experiences of older Americans from three perspectives: those of the older adults themselves (n=81),i their kin (n=49), and professionals involved in the move (n=46). The primary participants were older adults, either single (n=43) or married (n=38), when both agreed to participate. The principal investigator recruited study participants within 50 miles (of either pre-move or post-move location) of a university research center in the Midwestern United States. Participants were located through circulating recruitment flyers, attending meetings of older adults and seeking referrals from agencies serving older adults. Most were Caucasian (n=77, 95.1%) with the remaining being African-American (n=3, 3.7%) and Asian (n=1, 1.2%). There were 22 males and 59 female participants, whose ages ranged from 57–91. Kin included adult children and their partners, nieces, and grandchildren, siblings of the older adults, and friends who older adults identified as close friends during the move. Professionals were identified as those who supported the older adults in the moving process during any phase. Older adults were considered to be relocating if they were moving to a long-term care facility or to an apartment, house or condo. All names have been changed for confidentiality purposes.

Data Collection

Two primary qualitative data collection strategies were used: 1) semi-structured interviews and 2) participant observation.

1) Semi-Structured Interviews

The interviewing process led to “co-creation of meaning” (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2006, p. 134), offering the interviewer and participant to see the interviewee as the expert on moving, yet be prompted by the principal investigator to clarify, contrast other experiences, or go back to points that seemed particularly salient to the research questions during the interview (Padgett, 2008, p.111). The principal investigator’s reactions to interviews (Padgett, 2008) were also documented in the field notes. Interviews with kin and professionals provided data on the move from their perspectives. Interviews with relatives helped the principal investigator understand their roles in the moves. Expert interviews yielded a wider perspective (Padgett, 2008) on moving processes and conversations.

2) Participant Observation

As the principal investigator developed relationships with participants, the principal investigator actively participated in the moving process. A key to anthropological research is participant-observation, in which the principal investigator can better understand the process (Geertz, 1973) by both observing contexts and participating in the process. This method enhances the interview process, as much of the discussion in interviews is about the physical space, objects, and activities involved in moving. The principal investigator’s participation included packing objects, working at garage sales, and walking through the original and new residences. The principal investigator also used participant observation methods to gather data on the degree of space reduction (square footage and layout) between the original residence and the new residence, and the magnitude and types of possessions (e.g.: special collections of maps) involved.

The principal investigator recorded observations including information about the setting, including sensory observations, activities, and participants’ present, as well as analytical reflections including new questions or themes, relevance of observations to previous observations or themes, and reflections on the principal investigator’s role (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2006). The principal investigator also photographed rooms in the primary participants’ old and new homes to document the arrangement of their possessions to supplement the principal investigator’s field notes in addressing the process of leaving one’s home and creating a new one. Participant observation served as a method of “crystallization” (see Richardson, 1994 in Denzin & Lincoln, 2006) to establish validity of the interview data as a way to reduce both respondent bias and reactivity of principal investigator in asking or probing only certain questions (Padgett, 2008; Denzin & Lincoln, 2006).

Analytical Approaches

To analyze the data, the principal investigator selected interviews to transcribe, based on quality and content. The principal investigator also iteratively analyzing the interview data, transcripts, field notes, documents, and photographs for emergent themes. As the principal investigator is a trained anthropologist, there was epistemological emphasis on being open to emergent themes in order to avoid “constraints on outputs” when analyzing the data (Patton, 2002, p. 39). In the anthropological tradition, there was an iterative nature to the content analysis, particularly searching for examples that fit the theoretical lens of the Baltes and Baltes, 1990 model. As another validity check, the principal investigator solicited reactions to formal presentations of the research findings and held further conversations with study participants before conference presentations and in preparation for publication (Rubin & Babbie, 2012).

Findings

In this section, we provide ethnographic examples of how Baltes and Baltes’ (1990) model can be applied to both couples and other members of a kin network.

Applying SOC to couples: Strategic Reactions to Health Concerns

Moving requires an understanding of a present and future self in terms of health and mobility. For many couples, current health needs and the possibilities of disease progression for one member of the dyad were major factors in the timing of the couples’ moves. In two cases, the Keiths and the Jacksons chose to move because the husbands had serious heart conditions and the upkeep on their previous houses was becoming more difficult. Both husbands maintained their homes meticulously and yet, due to their health challenges, would not be advised to continue exerting such effort towards home maintenance. Both wives anticipated future complications with their husbands’ health. Mrs. Jackson stated that she could not have made the move without her husband, so moving while his health allowed him to actively participate in the move was a good choice for them.

Mr. and Mrs. Johnson provided an example regarding disease progression. The couple primarily moved because Mrs. Johnson has Multiple Sclerosis. They have chosen new roles as communication liaisons to support overseas work because of her diagnosis rather than participate in international mission work in retirement as they had planned. On moving day, the principal investigator asked Mrs. Johnson whether this was the best year for the move. She said that her husband had been plagued by back problems this year and that she herself would never walk quickly again. Moving this year, and having his children do most of the lifting of heavy items during the actual move would actually help them both optimize their health challenges.

Applying SOC To Couples: Partner’s Interest In Moving

Sometimes, couples relocate because one partner expresses serious interest in moving even though the other may not wish to relocate. For example, Mr. and Mrs. Paul lived on a farm on the outskirts of town. It was not their first move as they referred to a difficult, prior move from another state when they left a farm in the town where the family still had ties. Nevertheless, they had been in this town a long time, enjoying the peacefulness that a rural life offered them. They had a home, a barn and farmland, which they partially leased to a farmer. They had four grown children who lived in what Mr. Paul described to the principal investigator as some of the best cities in the world. They had hopes that one of their children living overseas might consider taking over the property but did not see that possibility happening soon. That daughter and her husband had built internationally driven careers and they were still engaged in working to send their own kids through college.

The principal investigator visited their lovely home several times, taking in the quiet that their internal and external surroundings seemed to foster. It was furnished simply yet elegantly and they talked about the ways that they loved their home. The principal investigator soon discovered that Mr. Paul did not wish to move at all. They decided not to sell their home and barn (which housed his workshop) because he intended to go back and work on projects. He planned to return again and again to the space that he loved.

Mrs. Paul wanted to move because she had faced some health concerns and, being over 80 years old, wanted to move for peace of mind. She had identified a retirement community in their town and hoping that her life would be optimized by the social possibilities available in the community. She stated that they lived a quiet life, unlike her friends, who were busy volunteering and involved in community activities. She and her husband had lived on a schedule for many years and enjoyed the slowness of their days. She looked forward to having the possibility of friendships in the retirement community as a way to broaden their lives. Overall, she was excited about the move and in subsequent post-move interviews, she still seemed happy, having started walking with a few neighbors and participating in exercise classes.

Mrs. Paul: But, but I think that because, I’ve, my attitude toward our move was that it was the right thing to do.

Principal investigator: Yeah.

Mrs. Paul: And I, so my, my attitude was always very positive that this is something we can do, this is good for us.

Alternatively, Mr. Paul was not excited about the move, and even after the move, he stated in a soft voice that he was “still in transition”. He moved only for his wife, because he wanted her to be taken care of, in case anything should happen to him. He would not want her to be left alone with the home and adjacent farm. Interestingly, similar to conversations with other couples, both Mr. and Mrs. Paul presumed that he would die first. However he told the principal investigator that if his wife passes away first, he would move back to their home…even if he ate scrambled eggs three times a day (field notes).

Mr. Paul: I’m still in transition.

Principal investigator: Yeah, it’s ha, it must be hard.

Mr. Paul: Yeah.

While, Mr. Paul is “still in transition,” Mrs. Paul has become very involved in the retirement community. She has joined an informal walking group and attends exercise classes. Later in the conversation, she states that there is also the possibility of becoming too busy in the new retirement community. She says, “I, some years ago I decided I did not want to join things. …we like the life where we aren’t, where we don’t have a lot of, um, commitments. Cause we really believe if you join something, um, you should be a part, I mean, be willing to serve.” Mrs. Paul brought up another couple later in the conversation which serves as a poignant comparison.

Mrs. Paul: But I thought it was interesting that the Keiths was just, was just the other way around for them. She didn’t want to move, because the home they lived in (Name of Town) was a home that they had built especially for retirement. On a lake and their children and grandchildren could come and they just, they had wonderful memories associated with that place. But, ah, but the, but Mr. Keith wanted, he was more interested in moving. And they really were quite charmed by the by (unclear) she too thought it was a very charming, ah, setting. Well then when she, after she got here, what she told me was that is that she, ah, they went home, back home to (Name of Town) and she went to their house and she said, ‘I sat down on the hearth in the living room and I thought, No, I’m glad we’re now at the (Name of Retirement Community).’ I’m, she was able to ah, get a sense that this they had done the right thing. So, I think maybe, it just, take you some time to, I don’t know do you feel like we’ve done the right thing?

Mr. Paul: I hope so.

Mrs. Paul said the other couple had owned a beautiful home that they loved. She also noted that Mr. Keith wanted to move, rather than Mrs. Keith, and that it was the “other way around for them” (line 2). In talking about them, she is also talking about her husband’s and her experience. She says that Mrs. Keith was able to say, after living in her new home, that she was happy at the retirement community. Mrs. Paul then poses it in moral terms, “I’m, she was able to ah, get a sense that this they had done the right thing” (lines 14–5). Mrs. Paul switches here from “I’m” to “she” to refer again to Mrs. Keith’s experience rather than her own. However, in the subsequent line, she says, “So, I think maybe, it just, take you some time to, I don’t know do you feel like we’ve done the right thing?” (line 15–16). In this case, she is now addressing her husband, using an authoritative assessment “I think, maybe, it just, take you some time to…”, leaving one phrase, “take you some time to” speaking about his possible adjustment, perhaps. Yet she avoids that word and instead switches to a question approach. Her question asks him, using “you” about whether “we’ve” made a correct choice; the switch from first person to the couple as the unit of analysis is striking. Especially since he really did not want them to move at all. He answers with “I hope so,” an ambivalent statement analogous to his first declaration, “still adjusting.”

Mr. and Mrs. Paul also struggled with the timing of the move: she wanted to move in the fall, he preferred the following summer. They split the difference by moving in February. Since they decided to rent and not to sell, the couple had the additional burden of preparing their home (excluding the barn) for rental. Thus, they worked steadily on preparing their home for the move by showing the principal investigator their progress in sorting and discarding each time the principal investigator visited. All the while, they both held the heavy realization that one partner was reluctant to move. Out of love for his wife, Mr. Paul was willing to do so. Therefore, his participation in the preparations, and the move would optimize his wife’s life. Mr. Paul’s plan of moving out of his home illustrates the interpersonal nature of the SOC model in the fact that he moved for his wife. To optimize his wife’s life, should he pass first, they are selecting living in a less demanding environment compensate for both their current challenge of maintaining their home now, and the perceived future challenge for his wife of maintaining their home upon his death. He expresses great sadness on leaving his home, which illustrates to his wife and their children that his decision to move is a way to optimize his wife’s life rather than his own. He and his wife have chosen to move to a place where professionals may later assist them in “compensating” by providing home maintenance, meals, and housekeeping. Moreover, Mr. Paul’s move also exemplifies that researcher’s use of the SOC model may involve a longer time horizon (of several years, in this case) to discover how the selection of living in a less demanding environment assists older adults in achieving the goal not only of maintaining one’s own independence but also that of optimizing a spouse’s life.

Applying the SOC to kin: Optimizing Peace of Mind

We shall now focus on the ways moving can be viewed as optimizing members of a kin network and the ways kin serve in compensatory roles. Sometimes, older people undertake moves to optimize the emotional and logistical needs of their kin. For example, Mrs. Ash’s daughter, Karen, was deeply concerned about her mother in the winter. She encouraged her mother to leave before the winter season fell. Given the scope of work needed prior to the move, Mrs. Ash wanted to stay one last winter. Mrs. Ash lived on a corner, with the driveway situated on the side of her house while her mailbox faced the street. To comfort her daughter, who lived out of state, Mrs. Ash promised that, to prevent falls, she would drive to the mailbox, rather than walk to it.

Some study participants do not have adult children or partners; they involve other relatives or kin in the move. One night the principal investigator was having dinner at a Chinese restaurant with three nieces who came to help their aunt, Mrs. Sand, move.ii

Principal investigator: So I have to ask you guys, and I ask everyone this, but um what do you think this move will mean to your aunt?

Niece 1: iiiI think it’ll be great.

Niece 2: It’ll make her life much easier.

Niece 1: To be on one level.

Principal investigator: Okay.

Unclear: To not have to worry that you’ll, you know, fall. To have the garage right attached to the house. To be able to get in the car and go. To not worry about who’s going to mow the lawn or who’s going to shovel snow and all that I think that’ll be great.

Principal investigator: Okay.

Unclear: And you know to just have other people around.

Unclear: I think–It’ll be a relief for you. For all those reasons.

Principal investigator: Okay, a lot of people have told me that.

Mrs. Sand: And it’ll make the next move easier you know when I can’t live there anymore for health reasons.

Principal investigator: It’s sort of a plan you know a plan and a safety net.

Mrs. Sand: Well I go to the [Name of Retirement Community] home.

Principal investigator: Yeah.

Unclear: Ah we figure you’ll just live to a hundred and just keel over.

Unclear: (laughter)

Unclear: Probably at an elder hostel on a zip line.

Principal investigator: In Antarctica.

Mrs. Sand: I’m going to Alaska—Antarctica.

Principal investigator: Yeah you told me. I was telling her it’s your post move reward.

Unclear: I think it’s even going to make traveling easier because you won’t have to worry about the house.

Mrs. Sand: That’s right.

In this conversation, one niece points out all the logistical benefits that Mrs. Sand will enjoy in her new home, while also emphasizing that a new residence will also make it easier for her to travel. Applying the SOC model, the move will also optimize the lives of her kin, by offering peace of mind to her three nieces, the closest of which lives five hours away.

However, these actions such as relocation also impose obligations. For example, when relatives come to assist with a move, they may not accept the older person’s wishes about number and types of possessions. After unpacking her aunt’s tea collection, one niece told her aunt that she did not need to buy more tea. Her aunt, Mrs. Sand, told me that soon after, she went to the store and bought three more boxes. It is uncertain whether her niece would laugh about this defiance or be disappointed. Will her niece be able to see past the tea bag collection to the peace of mind attained for her aunt and for herself in this new environment? For years to come, their relationship may involve the compensating roles that the niece may play in helping with her aunt’s material accumulation (e.g., more sorting, garage sales, etc.), despite the optimized peace of mind her relatives will enjoy.

Applying the SOC to Kin: Optimizing Freedom

The emotional and logistical involvement of kin in the moving process varies. Sometimes older adults design and execute the relocation plans and kin are directed to perform certain minimal duties, including reclaiming their childhood objects that their parents had been storing, or taking objects that are not being moved. Sometimes these objects are taken out of duty, and sometimes out of desire. Importantly, older adults’ moves affected kin far beyond the material circulation of possessions. Moving could also be an opportunity for kin to optimize their lives by experience freedom in other ways.

For example, Gordon, the adult son of Mr. and Mrs. Keith, would often bring his dog when he came to visit his parents two and a half hours away from his home. One night when the principal investigator was talking with him after he had driven over, the principal investigator asked what his parents move meant to him. This conversation took place in the final month before his parents’ move in late fall. He said, “This is done now and I’m done working it.” He and his sister had been very involved in the move. His sister, Nancy, would come every other week, spending the night Monday through Thursday to help her parents get ready for the move. The Keith family endured a stressful summer, with Mr. Keith suffering a broken leg, followed by an anxiety disorder that affected the whole moving preparation. Gordon was thankful that the summer was behind them because his parents’ “nebulous future” seemed more certain. Gordon clarified, “It’s a weight off of my shoulder…well, because first of all, having to come out this way…I’m glad that I’m available to do it. I’m really, I’m grateful for that. But I would like to be free of having to do that. Now I can launch into a new life.” He further clarified that “I can move away now” and that he had always wanted to live in a different part of the country. Here we see a family deeply involved in the moving process, and yet also family members feeling that the move will optimize their lives.

This optimization comes with the expectation that the adult children will become involved in significant packing and unpacking chores. The Keiths move to within two miles of their daughter has created the potential for an imbalance of responsibility on adult children. Over time, their daughter may feel the need to reciprocate her parents’ moving in other ways, such as providing transportation for shopping or medical visits. With many children of her own, the Keith’s daughter has other responsibilities that she will have to balance with her obligations to her parents. Her brother Gordon faces the possibility of moving himself, yet, with his parents now 45 minutes away from him, it is uncertain whether he will still feel free to move away as his parents age. Though their housing provides a less demanding environment with supports in place, if his parents experience changes in their health status, he may not feel the same freedom expressed during the moving period.

Applying the SOC to kin: Optimizing Caregiving

Another reason that older adults moved served to optimize the lives of their adult children. The data indicate that the reason was intentionally not wanting to burden their children (see also Blinded for Review, under review). For example, Mrs. Jenkins stated in an interview, which took place a few years after her husband’s death:

Well, you know, (husband) and I had actually taken out long-term care insurance years ago. When he retired. Because at that point it was clear to us that our kids were going to have their own lives. That’s how we raised them…We raised them, and we, we didn’t live near our parents. My parents lived in (a different State) and his were in (a different State) and (a different State), so you know we’re not so much about that…So, you know, maybe we laugh and said, you know, they’re not gonna take care of us. Not that we’d, I know, I know they love us and…

The motivation can also result in adult children trying to convince them that their moves near them does not burden them. For example, an adult daughter whose mother, Mrs. Ash, age, 91 at move, was moving across state lines emphasized, “I keep telling her I’m happy that’s moving there, it’s not a burden, I’m trying to convince her of that” but the mother worried that even though they were not living together, the geographical closeness might be burdensome.

In addition to move itself, the decision to move nearby adult children and other kin was an intentional decision by older adults to optimize the lives of their kin. In one case, Mr. Lewis explained that the previous moving experiences of older relatives, as well as their experience with moving their own family 27 times, affected their relocation decision.

Mr. Lewis: The move is a philosophical move.

Principal investigator: Okay.

Mr. Lewis: It’s a philosophical move to basically, uh, two, two major objectives. To, to be help and assistance to our to our kids and grandkids and number two to make it so that our kids didn’t have to go out to (location) in the middle of nowhere and pick up the pieces.

Here, Mr. Lewis asserts that he is moving to circumvent his children’s possible needs to move closer to them should that become necessary. Secondly, his children would not have to “pick up the pieces” because by living nearby, they will know each other’s homes, and lives more in-depth rather than superficially during periodic visits. Lastly, he asserts that by moving at a younger age (he and his wife moved in their early 70s), the couple would have opportunity to establish social connections in their new community.

He alludes to his grandmother’s experience of moving-in with his parents and his own caregiving experience of moving back to the town where his mother and his wife’s mother were both in a nursing home. For the latter, this relocation entailed caring for their mothers and disposing of their estates, placing their own lives and dreams essentially on hold.

Ekerdt and Sergeant (2006) suggest that moves become family lore. The recalling of how others aged becomes a script to inform their own decisions. Underlying the content of a story may be a moral message, that moving is a way to express one’s love. Or, that putting one’s life on hold shows the ultimate love for a parent. The retelling of narratives will be subject to layered interpretations. A generation ago, Mr. and Mrs. Lewis moved themselves rather than having their mothers move to be caregivers.

Applying the SOC model to kin: Adjustments and Compensations

The moving processes of older adults may affect the entire kin network by requiring adjustments that can be understood as expected and unexpected compensations. While a few older adults in the study who had kin planned and executed their moves with little help from that kin, most of the study participants had kin participation in various stages of the moving process. For instance, relatives packed boxes, supervised garage sales, hung pictures, and assembled tables. One adjustment mentioned as a part of the move is the receiving of possessions that adult children or other kin experienced. When the principal investigator went out of state to visit Mrs. Ash in her new retirement community, the principal investigator stayed at her daughter and son-in-law’s home. Her daughter Amanda’s home was lovely, remodeled with an open concept kitchen that opened up into both an informal place to eat and a formal dining room. The principal investigator was delighted to find, in the formal dining room, furniture from her mother’s home that the principal investigator had seen many times. Also, the principal investigator saw stacks of boxes. Her mother had moved several months before the principal investigator’s visit.

Amidst her daughter’s furniture lay the portion of the objects her mother had identified and saved for her. Mrs. Ash had used a color-coded labeling system that by the end of the stay in her home of 51 years, had stickers on many of the remaining items. The categories included a blue circle for her son, a red circle for her daughter, a green circle for the antique dealers that she listed by the town that they were from, a yellow circle for the house sale and a white circle for items to remain with her in her new space. A light green rectangular post-it indicated the name of the retirement community. The latter two items seem to be travelling to the same new space.

Of these items given by her mother, should these also be interpreted as ways to materially optimize her life in addition to moving within four miles of her daughter? These material objects, at the time of the principal investigator’s visit, had not been absorbed into the home of Mrs. Ash’s daughter, Amanda. Her daughter had other preoccupations, such as an impending divorce, which leads to another point when applying the SOC model to networks. The moves of older adults occur within a kin network whose lives are always subject to change.

Another adult daughter, Heather, wrote the principal investigator an e-mail explaining how her life had changed because of her mother’s move. Besides scheduling time during the week to help her mom with bill paying, errands, and visiting, the other major change has been holidays. She writes, “Since I was 18, I have not lived near a member of my extended family. During the times when we did not travel to see our extended families, my husband and I developed our own holiday traditions, which often included local friends and neighbors. My mom has now become part of these events. She has done a fantastic job of rolling with the punches with these changes.”

Heather also explained that she had been able to see other family members as they were travelling to the city where she resides, which is a different state than the one in which her mother lived for many decades. However, other relatives she sees less frequently as her mother’s home had been geographically centered for some other kin. She also noted a change in her husband, or Mrs. Rogers’ son-in-law. “The other change has been for my husband to help out, especially when I am out of town on trips. I was traveling last week and he went over and took my mom out to dinner and visited with her for a little bit.” Kin relationships are being transformed both in the reorientation of geographically far kin and the involvement of geographically near kin.

Heather also described new areas she has had to learn to navigate, such as the “bureaucracy of senior care,” as well as being conscious of doing things with her mother that are not related to logistical and medical concerns. She has frequented several gardening shows, e.g. peony festival, and helped her mother at the retirement community with a scheduled and sanctioned pulling of garlic mustard. Heather honestly concludes the e-mail stating, “I am very glad I had experience raising kids and with also elder care before my mom moved here. With my mom’s medical issues (vision and mobility), I knew what to expect and the type of resources I would need to find to help us with her move and getting her readjusted. Without this previous experience, I would have been very overwhelmed by the added responsibilities of eldercare. It would be different if parents move nearby while they are still in good health.”

Kin relationships can be transformed by an older adult’s move. Even questions such as “where to hold family gatherings?” and “will family fit into the new spaces?” are raised. These adjustments lead to changes that coincide with a move. Other older adults told me that they had already begun celebrating holidays at their adult children’s or other kin’s homes, so the move did not represent such a change for them. Some adult children and grandchildren had to readjust their cultural practices to account for the moves of older adults.

A Thwarted Move: Alternative Selections & Optimizations

As this move was set during after the recession, kin were also affected when the older adult did not select “living in a less demanding environment.” For some, they are worried about the affordability of senior living. Others, like Mrs. McGee, cancelled their move to support others in their kin network. She explains, “I am the richest of the people I love” and reacted to family members’ job losses and financial challenges by contributing resources to them. Although she did not move, and optimize their lives in the ways discussed above, she optimized their lives in other ways. There are other implications to Mrs. McGee’s cancellation of her moving plans. She told me that in a recent rehabilitation of her knee, she had to strategically navigate her home’s stairs to do laundry in the basement and to enter the home, for all of the entrances require the use of stairs. She told the principal investigator that she focused on leading with her strong leg first going down with the stairs and going up the stairs, she would lead with her weaker knee as suggested by her physician. As she remains in this living environment, her family may be called in to support her in compensatory ways for her needs in the future. This is one example of how family networks are affected by moves undertaken and moves thwarted.

Discussion

The SOC model sheds light upon the process of older adult relocation as it offers a way to understand relocation in terms of optimization of functioning. Further, it can also be applied interpersonally to understand dyadic relationships and relationships with adult children and other kin. By applying the SOC model, it is possible to understand the strategies that older persons employ to optimize their lives. In order to maintain their independence, the individuals selected living in a less demanding environment. Studies have shown differences between resource-rich and resource-poor older adults in terms of the SOC model (Jopp & Smith, 2006; Jopp & Schmitt, 2010). Given the resource-rich nature of the study participants and length of time to plan and execute a move, the components of this analysis may be unique to the set of resources available to them.

By selecting living in a less demanding environment, the participants optimized their lives in multiple ways. Emotional reserves were often optimized because of the resulting peace of mind, and feelings of liberation. However, not every person moving experienced this relief and some could not relocate due to economic concerns (see Author, 2014). For some older adults, their lives were optimized because their future health care needs would be addressed in the new environment. In terms of compensation, living in a less demanding environment often meant living in a residence with a spatial layout that could compensate for physical issues that may arise. Also, for some study participants, compensatory services may be available at retirement communities, such as provided meals, or interior and exterior housing maintenance. As the original paper notes that living in a nursing home is the selection of a “less demanding ecology” (p. 24), we can expand the application of the model to housing available for older adults in the new millennium. Thus, by selecting living in a less demanding environment to achieve the goal of maintaining independence, the older adult may move between family caregivers to formal caregivers at some point. As we consider optimization interpersonally, Figure Two shows how selecting living in a less demanding environment “optimizes” well being of both spouses and kin in different ways.

Fig. 2.

Study Limitations

Due to the prolonged engagement, the researcher obtained multiple points of view on relocation for each kin network. However, due to the nature of the study and the study site, there was a limitation in terms of terms of racial, ethnic and economic diversity. Additionally, there were no persons in the study who were not assessed by the researcher as relocating voluntarily. Another limitation was an inability to evaluate the application of the SOC model in sudden relocations of older adults, such as due to acute medical needs after release from hospital. It is possible that these quick decisions may involve more professionals (such as discharge planners, nurses or doctors) and the SOC may not be the most appropriate theoretical model for understanding interprofessional decision-making input in these cases. On the other hand, moving in a slow manner allowed for anthropological engagement in a sustained way. Barusch et al. (2011) argue, “prolonged engagement helps a researcher to identify and ‘bracket’ his or her preconceptions, identify and question distortions in the data, and essentially come to see and understand a setting as insiders see and understand it” (p. 12). In this case, the ethnographic approach to the project helped me understand the detailed manner in which older people plan and execute their moves. This project highlighted that developing trust in long-term engagement with older adults and their networks is crucial if a researcher is to be allowed access to their emotional and physical spaces.

Optimization from a Network Perspective

Living in a less demanding environment can variously optimize partners or spouses’ lives. As in the case of the Pauls, moving may create an easier living situation for a spouse after the death of the partner. Other participants felt that if one spouse died, they would not want the other left with the job of moving and all that it entails. Therefore, couples often moved together to position the remaining partner in an optimized state. Kin, such as the Keiths’ children, also felt that their lives were optimized by their relatives’ transition to living in a less demanding environment because they were free to move away and were relieved of managing the logistics and providing the physical labor of moving. Many expressed relief that lawn care and other maintenance tasks were no longer a concern.

Compensation from a Network Perspective

In expanding the SOC model to include interpersonal optimization, we must also consider the obligations that may accompany moving. While moving can optimize the lives of partners and kin, it is also important to consider how one act of moving may be exchanged for future emotional and instrumental support from spouses and kin. If the new living environment is close to kin, it may bring on the expectation of greater family involvement in the older adult’s life.

Kin may not be able to resist requests or redirect them to facility workers. The SOC model of adaptation shows that older adults and kin may welcome some changes and resent others. In broadening the SOC model from an individualistic perspective of strategic functioning to encompass kin networks, follow-up studies with the same sample may further highlight the longer-term challenges experienced by the kin networks as well as the older adults.

An anthropological lens on housing transitions also sheds light on the SOC model itself. The attention to historical process in ethnographic work shows that optimization and compensation unfold within a kin network beyond the individual. There may also be other factors at play in understanding housing transitions in the light of the SOC model. First of all, the model presupposes an aggregate of choices that can be chosen “from” at a specific moment in time. In reality, choices may ebb and flow within a social landscape. Second of all, some choices may be comprised of many elements, so it may be impossible or undesirable to decouple them. For example, a move out of one’s home across state lines to live near kin is at once leaving of a home and community as well as a move away from independence. Second, a decision about moving near kin at one moment in time, may presuppose the availability of kin, when the kin’s own employment uncertainty and potential relocation may affect the older person’s post-relocation experience. This was particularly evident in some of the data collected in the aftermath of the financial crisis in this project (see Author, 2014). Third, the resultant social constructions of selection, optimization, and compensation can have a host of meanings for older persons, their kin, professionals, and others. Definitions of optimization and compensation may develop over a lifetime as people learn what makes them “feel” successful, and what or who appears successful at different moments of time. Success in adolescence or early adulthood may have different meanings than in later adulthood. An important part of the SOC model is the recognition of the physical and cognitive changes occurring due to aging. An enhanced model would include consideration of cultural and cohort differences in optimization and compensation, acceptable options for optimization and compensation, and an interrogation of these processes from multiple perspectives.

Implications and Future Research

By applying the SOC model interpersonally, this paper highlights the impact of relocation on couples and other kin in terms of optimization and compensations occurring when the older person relocates. In subsequent research, we can examine the differential gains and loses of relocation for the various parties involved. If we consider moving as a family affair, we must also acknowledge and support the different types of families making relocation decisions, in terms of cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds and sexual orientation. Future research can track various kin networks’ functioning and also concomitant obligations that occur. Longitudinal studies may further highlight the challenges experienced by the kin network that may not always be seen as optimization. Also, the SOC model could be applied interpersonally to relocation in cases of sudden relocations or in cases where relocation is not seen as voluntary.

On a policy level, we can consider how to support older adults and their networks to optimize their housing. A component of the Affordable Care Act is that every older American is entitled to a wellness visit for preventive care. In addition to medical screenings, this consultation could also help link older adults with home- and community-based services, provide information about home modifications and assess if relocation is in the older adult’s best interest. Second, attention can be paid to helping older Americans evaluate their assets as they consider their housing needs. Federal state and local initiatives for financial literacy may help older Americans plan for their housing needs. Helping older adults plan will also optimize the lives of other family members in various ways.

Conclusion

The Baltes and Baltes (1990) model provides a useful lens for understanding how lives are optimized and what types of compensations support these optimizations. The lives involved may be those of older people as well as kin in their social networks. However, these choices and strategies, understood through the theoretical lens of the SOC model, are made in contexts of aging, family dynamics, and financial constraints. Rather than having others drive their moves, these older adults in this study retained and asserted their agency. Older adults strategized to optimize their lives. In light of their aging bodies, changes, and health concerns, older adults in this study chose to move.

To develop the SOC model for qualitative work, we need to understand how the SOC occurs over time and whether older persons explicitly mention strategies to optimize their lives. This study, with longitudinal potential, opens up new ways to consider interpersonal networks in the light of the SOC model. By utilizing a longer term time horizon, we can understand that moving involves cycles of obligation within families, complicated with benefits and disadvantages, and which are often, nevertheless, expressions of love.

Fig. 1.

Footnotes

While some of the older adults were interviewed in these distinct phases (pre-move phase n=25; post-move phase n=17), most older adults, their kin and involved professionals (e.g., real estate agents, handymen or women) participated in the project through three stages of movingi (pre-move, moving day, post-move).

Several men in the study expressed sadness over giving up tool collections given the effort taken over decades to assemble them. By retaining the workshop, he did not have to go through this process.

In this recording, at times, it is difficult to distinguish between the voices of the nieces present.

Contributor Information

Tam E. Perry, School of Social Work, Wayne State University

John F. Thiels, Advance Research Computing, University of Michigan

References

- Author (2015)

- Author (2014a)

- Author (2014b)

- Author (2013)

- Baltes PB, Baltes M. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In: Baltes PB, Baltes M, editors. Successful Aging: Perspectives from the Behavioral Sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes BB, Heydens-Gahir HA. Reduction of work-family conflict through the use of selection, optimization, and compensation behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(6):1005–1018. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caro FG, Yee C, Levien S, Gottlieb AS, Winter J, McFadden DL, Ho TH. Choosing among residential options: Results of a vignette experiment. Research on Aging. 2012;34(1):3–33. doi: 10.1177/0164027511404032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter BD, Mak W. Caregiving Couples. Generations. 2007;31(3):47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA. Evaluating everyday competence in older adult couples: Epidemiological considerations. Gerontology. 2011;57:173–179. doi: 10.1159/000320325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekerdt DJ, Sergeant JF. Family things: Attending the household disbandment of elders. Journal of Aging Studies. 2006;20:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund AM, Baltes PB. Life-management strategies of selection, optimization and compensation: Measurement by self-report and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82(4):642–662. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund AM, Baltes MM. The Orchestration of Selection, Optimization, and Compensation: An Action-Theoretical Conceptualization of a Theory of Development Regulation. In: Perrig WJ, Grob A, editors. Control of Human Behavior Mental Processes, and Consciousness: Essays in Honor of the 60th Birthday of August Flammer. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Eribaum Associates, Inc; 2000. pp. 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight. The Interpretation of Cultures 1973 [Google Scholar]

- Hesse-Biber SN, Leavy P. The Practice of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jopp DS, Schmitt M. Dealing with negative life events: Differential effects of personal resources, coping strategies and control beliefs. European Journal on Ageing. 2010;7:167–180. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopp D, Smith J. Resources and life management strategies as determinants of successful aging: On the protective effect of selection, optimization, and compensation. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21(2):253–265. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungers CM. Leaving home: An Examination of late-life relocation among older adults. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2010;88(4):416–423. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A, Fausset C, Rogers W, Fisk A. Responding to home maintenance challenge scenarios: The role of selection, optimization, and compensation in aging-in-place. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2014;33(8):1018–1042. doi: 10.1177/0733464812456631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight SC, Buys LR. The involvement of adult children in their parent’s decision to move to a retirement village. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2003;22(2):91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Krout J, Moen P, Holmes H, Oggins J, Bowen N. Reasons for Relocation to a Continuing Care Retirement Community. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2002;21(2):236–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lavela SL, Ather N. Psychological health in older adult spousal caregivers of older adults. Chronic Illness. 2010;6:67–80. doi: 10.1177/1742395309356943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwak E, Longino C. Migration patterns among the elderly: A developmental perspective. The Gerontologist. 1987;27:266–272. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky MR, Lysack CL, Van Nuil J. Refashioning one’s place in time: Stories of household downsizing in later life. Journal of Aging Studies. 2011;25:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux JS. The “casser maison” ritual constructing the self by emptying the home. Journal of Material Culture. 2001;6:213–235. doi: 10.1177/135918350100600205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiske M, Lang FR, Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Selective optimization with compensation: life-span perspectives on successful human development. In: Perrig WJ, Grob A, editors. Control of Human Behavior, Mental Processes, and Consciousness: Essays in Honor of the 60th Birthday of August Flammer. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Eribaum Associates, Inc; 1995. pp. 35–77. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK. Qualitative Methods in Social Work Research. 2nd. Vol. 36. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M Quinn. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard JG, Tan J, Morrow-Howell N, Jung Y. Older adults retiring from the road: An application of the selection, optimization, and compensation model. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2009;19(2):213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin A, Babbie ER. Research methods for social work. 7th. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood S, Ruchlin HS, Sherwood CC, Morris SA. Continuing Care Retirement Communities. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Strough J, Neely T, Snyder K, Kimbler K, Margrett J. Relocating in later life: Reasons and strategies. The Gerontologist. 2004;44(1):473. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman RF. Why older people move. Research on Aging. 1980;2:141–154. doi: 10.1177/016402758022003.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young LM, Baltes BB, Pratt AK. Using selection, optimization, and compensation to reduce job/family stressors: Effective when it matters. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2007;21(4):511–539. [Google Scholar]