Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (SSc)-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) has become the leading SSc-related cause of death. Although various types of immunosuppressive therapy have been attempted for patients with SSc-ILD, no curative or effective treatment strategies for SSc-ILD have been developed. Therefore, management of patients with SSc-ILD remains a challenge. Here, we report a Chinese, female, SSc-ILD patient who was negative for Scl-70 and showed an excellent response to pirfenidone without obvious adverse effects. She had been suffered from dry cough and exertional dyspnea for 2 months. The chest computed tomography manifestation was consistent with a pattern of fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. The pulmonary function test showed isolated impaired diffusion. After 11 weeks of administration of pirfenidone, the dry cough and dyspnea had disappeared. Both of the lung shadows and the pulmonary diffusion function were improved. Pirfenidone might be an effective option for early SSc-ILD treatment. A well-controlled clinical trial is expected in the future.

Keywords: interstitial lung disease, pirfenidone, systemic sclerosis

1. Introduction

Thoracic involvement occurs in approximately 80% of patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc), and interstitial lung disease (ILD) is the most common manifestation of SSc-associated respiratory diseases.[1–3] Furthermore, SSc-associated ILD (SSc-ILD) has become the leading SSc-related cause of death. Although various types of immunosuppressive therapy have been attempted for patients with SSc-ILD, no curative or effective treatment strategies for SSc-ILD have been developed.[2,4] Therefore, management of patients with SSc-ILD remains a challenge.

Pirfenidone is a novel agent that exerts antifibrotic and antioxidant effects, and it has been recommended for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) according to an IPF treatment guideline published several months ago.[5] Since April 2014, pirfenidone has been used in China for IPF patients with mild to moderate lung function impairment.

Following several cases reports regarding the use of pirfenidone for SSc-ILD,[6,7] pirfenidone was attempted in a 62-year-old, female, Chinese SSc-ILD patient, who showed an excellent response to pirfenidone without obvious adverse effects. Written informed consent for the case report was obtained from this patient, and the consent procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

2. Case report

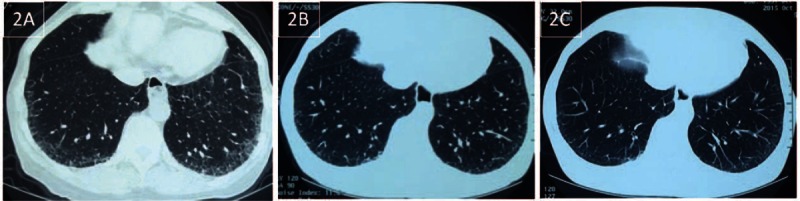

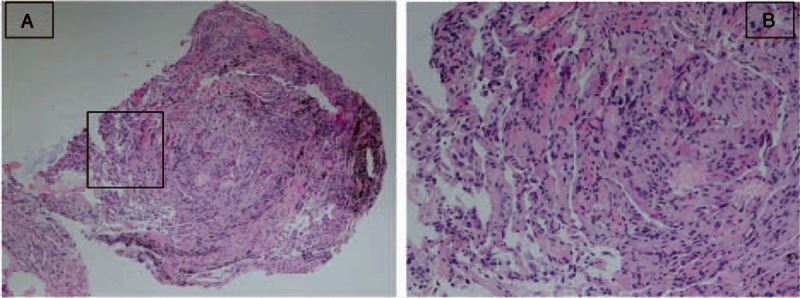

A 62-year-old Han woman with no medical history presented with a 2-month history of dry cough and exertional dyspnea (since February 2015). She had exhibited skin thickening on the fingers of both hands (Fig. 1) and Raynaud phenomenon for several years. She was a nonsmoker. Bibasilar inspiratory crackles could be heard. Her body weight was approximately 63 kg. An antinuclear antibody (ANA) test was positive with a speckled pattern at a 1:320 dilution. An anticentromere antibody (ACA) test was strongly positive at a 1:1000 dilution. However, an anti-Scl-70 antibody test was negative. The chest high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan was consistent with a pattern of fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (fNSIP) (Fig. 2A). Pulmonary function testing revealed isolated impaired diffusion: forced vital capacity (FVC), the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) to FVC (FEV1/FVC), 74%, 2.95 L (124% predicted); total lung capacity (TLC), 4.84 L (102% predicted); and diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLco), 4.02 mmol/min per kPa (57.9% predicted). Pulmonary hypertension was not detected by transthoracic echocardiography. A bronchoalveolar lavage fluid analysis showed a lymphocytic cellular pattern with 26% lymphocytes and a total cell count of 6.7 × 107/L. A transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) showed fibrotic interstitial pneumonia (Fig. 3A and B), and an fNSIP pattern was suspected. The patient was diagnosed with SSc-ILD after a multidisciplinary discussion with a pulmonologist, a rheumatologist, a pathologist, and a radiologist.[8] Because the patient refused corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, pirfenidone was prescribed for her. She tolerated pirfenidone well (400 mg 3 times a day), and she remained at this dosage for economic reasons. On July 15, 2015, after 11 weeks of administration of pirfenidone, the dry cough and dyspnea had disappeared. The bibasilar crackles and skin thickening of the fingers were also improved. Repeated chest HRCT on July 16 showed (Fig. 2B) improved lung shadows, and her lung function also exhibited improved diffusion with a DLco of 81.9% of the predicted value and a stable FVC of 2.98 L (126% predicted). Pirfenidone was continuously prescribed. The pirfenidone currently remains effective, that is, after 6 months of treatment with pirfenidone (Fig. 2C).

Figure 1.

Both of the patient's hands showed obvious skin thickening of all fingers.

Figure 2.

(A) Chest CT on February 28, 2015 showed bilateral, peripheral, basal, predominant, reticular abnormalities in the lower lobe with some ground glass opacities and without honeycombing. (B) The repeated chest CT on July 16, 2015 showed attenuation of the reticular and ground glass opacities in the bilateral lower lobe. (C) The characteristics of the repeated chest CT on October 15, 2015 were very similar to the chest CT on July 16, 2015. CT = computed tomography.

Figure 3.

(A and B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining for the specimen (H&E, ×60 for A and ×100 for B). Figure B is the magnification of the box part in figure A: The pathological features of the lung tissue harvested by transbronchial lung biopsy showed diffuse alveolar wall thickening with uniform fibrosis. Although the alveolar architecture was preserved, the alveolar space was obviously squeezed and wrinkled. No honeycombing, fibroblastic foci, or significant interstitial inflammatory cell aggregation were observed. These pathological manifestations were consistent with fibrotic interstitial pneumonia, and fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia pattern was the most probable pathological diagnosis.

3. Discussion

SSc is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by fibrosis of the skin and internal organs, especially the respiratory system. SSc-associated lung disease, including ILD and pulmonary hypertension, has become the leading cause of SSc cases,[3] and SSc-ILD is more common than pulmonary hypertension. It has been reported that up to 100% of patients with SSc have pulmonary parenchymal involvement on autopsy.[9] Although multiple clinical trials have been performed for the treatment of SSc-ILD, including evaluations of the efficacy of cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, and rituximab, no effective treatments for SSc-ILD have been developed.[2] Because interstitial fibrosis, including fNSIP patterns and UIP patterns, is common in SSc-ILD,[10] and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) might also play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of Sc-ILD,[3] antifibrotic therapy is now being attempted for SSc-ILD cases, for example, some clinical trials of new antifibrotic agents for SSc-ILD are expected.[3]

Pirfenidone (5-methyl-1-phenyl-2-[1H]-pyridone) has shown antifibrotic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties in in vitro and animal models.[11] It can attenuate the production of proinflammatory cytokines, collagen, and profibrotic cytokines such as TGF-β, and it can also increase the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines.[11] After many clinical trials, pirfenidone was approved due to its efficacy in the treatment of patients with IPF in Japan,[12,13] the European Union,[14] and the United States.[15] Currently, it has been conditionally recommended for patients with IPF according to this year's IPF treatment guidelines,[5] and since April 2014, it has been used in China for patients with IPF.

Recently, a clinical trial regarding the efficacy and safety of 8% pirfenidone gel for localized scleroderma showed that pirfenidone could improve the scleroderma skin severity score, durometer induration of scleroderma plaques, and even histopathological skin manifestations. Moreover, no obvious clinical or laboratorial adverse effects have been reported.[16] Although no outcomes of the clinical trials of pirfenidone for SSc-ILD have been reported until now, some case reports have been published regarding the efficacy of pirfenidone for patients with SSc-ILD positive for Scl-70.[6,7] In Miura's report, which included 5 cases with SSc-ILD positive for Scl-70, some of the patients showed improvement of dyspnea, some patients showed increased vital capacity, and some showed attenuation of ground-glass opacities (GGOs).[6] However, no data regarding the changes in TLC and DLco after the administration of pirfenidone have been recorded. Udwadia also reported the treatment of a case of Scl-70-positive SSc-ILD with pirfenidone. This patient showed improvement in effort tolerance, FVC, DLco, and 6-min walk test-associated parameters.[7] No progression of CT imaging was observed in this patient.

The present case might be the first of SSc-ILD case in China with reversal of lung function impairment and reduction of lung reticular shadows after pirfenidone administration. Our patient was negative for Scl-70 but positive for ACA, which is different from the reported cases.[6,7] Although the recommended dosage of pirfenidone was 1800 mg/d for Chinese patients with IPF, she received only 1200 mg/d due to economic reasons. However, she had improved respiratory and skin manifestations, obviously increased diffusion of lung function, and attenuation of reticules and GGOs on chest CT imaging after 3 months of treatment of pirfenidone. In Miura's report, GGOs, but not honeycombing, decreased after pirfenidone administration. These results suggested that pirfenidone might have better effects for improving early fibrosis than end-stage lung fibrosis.

There were some limitations of our report. First, TBLB, but not a surgical lung biopsy, was performed for our patient; therefore, the fNSIP pathological pattern was only probable. Second, the patient did not receive the recommended dosage of pirfenidone for economic reasons. Third, she had been treated with only pirfenidone for 6 months. The long-term efficacy and safety of pirfenidone were observed.

4. Conclusions

We reported a case of SSc-ILD in a Chinese woman who was negative for Scl-70 and positive for ACA and showed an excellent response to pirfenidone with no obvious adverse effects. Pirfenidone might be an effective option for early SSc-ILD treatment. A well-controlled clinical trial is expected in the future.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BALF = bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, CRP = C-reactive protein, DLco = diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate, FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FVC = forced vital capacity, HRCT = high resolution computed tomography, ILD = interstitial lung disease, IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, NSIP = nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, SSc = systemic sclerosis, TBLB = transbronchial lung biopsy, TLC = total lung capacity.

HH and REF have contributed equally to this study.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ferri C, Valentini G, Cozzi F, et al. Systemic sclerosis: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 1,012 Italian patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002; 81:139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silver KC, Silver RM. Management of systemic-sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2015; 41:439–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cappelli S, Randone SB, Camiciottoli G, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: where do we stand? Eur Respir Rev 2015; 24:411–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iudici M, Moroncini G, Cipriani P, et al. Where are we going in the management of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis? Autoimmun Rev 2015; 14:575–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline: treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An update of the 2011 clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 192:e3–e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miura Y, Saito T, Fujita K, et al. Clinical experience with pirfenidone in five patients with scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2014; 31:235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Udwadia ZF, Mullerpattan JB, Balakrishnan C, et al. Improved pulmonary function following pirfenidone treatment in a patient with progressive interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis. Lung India 2015; 32:50–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 Classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72:1747–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubio-Rivas M, Royo C, Simeón CP, et al. Mortality and survival in systemic sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014; 44:208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urisman A, Jones KD. Pulmonary pathology in connective tissue disease. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 35:201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter NJ. Pirfenidone: in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Drugs 2011; 71:1721–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azuma A, Nukiwa T, Tsuboi E, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171:1040–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taniguchi H, Ebina M, Kondoh Y, et al. Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2010; 35:821–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet 2011; 377:1760–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King TE, Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2083–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodríguez-Castellanos M, Tlacuilo-Parra A, Sánchez-Enríquez S, et al. Pirfenidone gel in patients with localized scleroderma: a phase II study. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 16:510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]