Abstract

Selective inflow occlusion (SIO) maneuver preserved inflow of nontumorous liver and was supposed to protect liver function. This study aims to evaluate whether SIO maneuver is superior to Pringle maneuver in patients undergoing partial hepatectomy with large hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs).

Between January 2008 and May 2012, 656 patients underwent large HCC resections and were divided into 2 groups: intermittent Pringle maneuver (IP) group (n = 336) and SIO group (n = 320). Operative parameters, postoperative laboratory tests, and morbidity and mortality were analyzed.

In comparison to the IP maneuver, the SIO maneuver significantly decreased intraoperative blood loss (473 vs 691 mL, P = 0.001) and transfusion rates (11.3% vs 28.6%, P = 0.006). The rate of major complication between the 2 groups was comparable (22.6% vs 18.8%, P = 0.541). Patients with moderate/severe cirrhosis, total bilirubin > 17 μmol/L, or HBV DNA> = 104 copy/mL in SIO group resulted in lower major complication rates.

The SIO maneuver is a safe and effective technique for large HCC resections. In patients with moderate/severe cirrhosis, total bilirubin > 17 μmol/L, or HBV DNA> = 104 copy/mL, the SIO technique is preferentially recommended.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a highly prevalent and lethal cancer. It is estimated that 500,000 to 1 million annual cases are reported worldwide,1 especially in the Asia-Pacific region. Partial hepatectomy is a potentially curative therapy for HCC patients,2–4 but liver resection may present intraoperative bleeding. Moreover, bleeding together with the subsequent blood transfusions can increase postoperative morbidity and mortality.5,6 In addition, blood transfusions, even in small volumes, have been found to enhance tumor recurrence in patients undergoing surgical excision of the HCC.7–9

Hepatic vascular control is effective in minimizing intraoperative bleeding during hepatectomy, especially for large tumors or those located in proximity to major vascular structures.3,10–12 The Pringle maneuver, a technique of transient hepatic inflow occlusion by clamping the portal triad, is the simplest and most established method for controlling afferent blood flow. However, the Pringle maneuver carries the risk of ischemia-reperfusion injury to liver, particularly in patients with chronic hepatic cirrhosis3,12–14 Ischemia-reperfusion injury caused by temporarily interrupted blood inflow to liver is a complex, multifactorial pathophysiologic process that includes intrahepatic adenosine-5ˈ-triphosphate (ATP) depletion, oxidative stress, and generation of inflammatory mediators.15,16

Selective inflow occlusion (SIO) techniques, with continuous occlusion of hepatic artery and intermittent occlusion of the portal vein supplying the tumor-containing portion of the liver, have been applied to reduce blood loss and injury to the liver function.17 In this study, this maneuver was applied to decrease ischemia-reperfusion injury of the remnant liver, especially for patients with cirrhosis. The advantage of this maneuver is to provide continuous arterial inflow of nontumorous liver by the hepatic artery during surgery.

Until now, the clinical advantage of using either the SIO or intermittent Pringle maneuvers (IPs) remained unclear. To address this issue, a retrospective study was designed to evaluate these 2 vascular control methods during large HCC resections.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

From January 2008 to May 2012, we evaluated 656 large HCC cases in our department. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Pharmacology in Tongji Medical College, and all the information of patients were kept private. Large HCC was defined with a tumor diameter >= 5 cm. Based on the maneuvers of hepatic vascular occlusion, these patients were divided into 2 groups: IP group (n = 336) and SIO group (n = 320). The diagnoses of cirrhosis and HCC were confirmed by histological studies of the surgical specimens. The following patients were excluded from this study: patients with a history of previous liver resection, patients with other concomitant major surgical procedures, such as splenectomy, bowel resection, bile duct resection, and esophageal devascularization. Data were recruited consecutively to address potential sources of bias.

Preoperative Evaluation

All patients had a chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasonography, and computer tomography portography vascular imaging. Preoperative laboratory blood tests included hemoglobin, platelet count, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate amino transferase (AST), serum albumin, serum total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, γ-glutamyl transferase, cholesterol, indocyanine green retention at 15 minutes after intravenous injection, creatinine, prothrombin time (PT), fibrinogen, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C antibody, and serum alpha-fetoprotein. Child–Pugh score was used to assess hepatic function for each patient. No patient received preoperative transcatheter hepatic arterial chemoembolization treatment.

Surgical Procedure

All surgical procedures were accomplished by 4 experienced liver surgeons from the same department, ensuring procedures performed in a standardized manner. Intraoperative ultrasonography was routinely used in all patients to assess the number and size of the tumors, and their relation to nearby vascular structures. The hepatic parenchyma was transected using an ultrasonic scalpel. Liver resections based on segmental anatomy were performed in all patients.

In SIO group, the portal vein, proper hepatic artery, right and left hepatic arteries, and bile ducts were dissected. The hepatic artery in the tumor bearing lobe was continuously blocked with a bulldog clamp. The portal vein was encircled with a rubber tourniquet in advance. During the parenchymal transection, all vessels and bile ducts were ligated on the preserved side. Small hepatic venous bleeding was ligated or coagulated. Intermittent portal vein occlusion was tightened when more bleeding from portal vein system was encountered during transection. Finally major hepatic vein was doubly ligated and divided.

In IP group, hepatic vascular control was performed through encircling the hepatoduodenal ligament with an umbilical tape and then applying a tourniquet until the pulse in the hepatic artery disappears distally. The porta hepatis was intermittently clamped with cycles of 15 minutes of inflow occlusion followed by 5 minutes of reperfusion.

Anesthetic management was accomplished by general anesthesia, and blood loss was estimated by taking into account suction volume minus rinsing fluids. Indications for red blood cell transfusion included blood loss exceeding 800 mL or a hemoglobin level below 5.6 mmol/L during operation or within 48 hours after surgery.

Postoperative Management

All patients received the same postoperative care. Liver function was monitored by ALT, AST, albumin, prealbumin, bilirubin, cholesterol, prothrombin time, and fibrinogen on postoperative days 1, 3, 5, and 7. Liver cirrhosis was evaluated according to the size of cirrhotic nodules in resected specimen, as we described previously.3 The tumors were diagnosed histopathologically. Postoperative complications and mortality within 30 days postoperatively were assessed based on the Clavien–Dindo classification.18

Statistical Analysis

Continuous, normally distributed variables are expressed as mean (±SD) or median (range), as appropriate. Student's t-test was performed for continuous data, and χ2 test was used for categorical data. All statistical tests were 2-sided. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistical significant. All statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 13.0 statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Baseline of Patient Characteristics

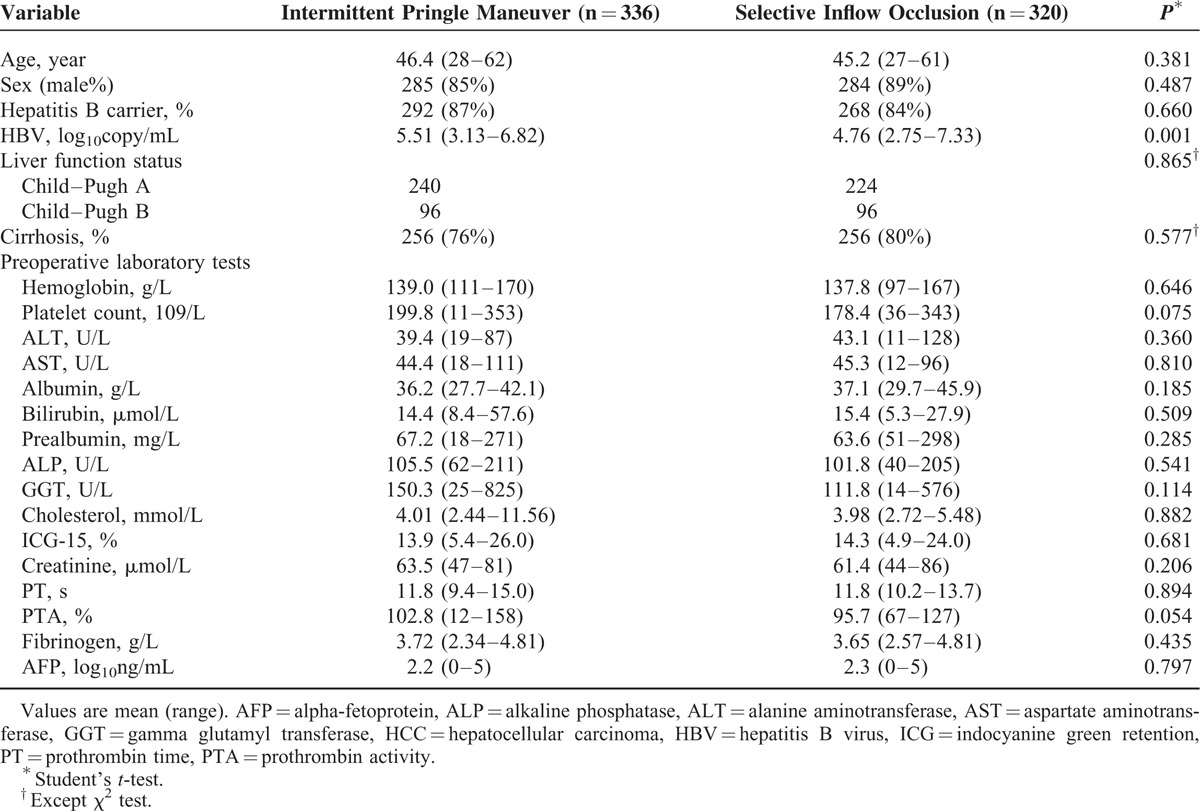

In total, 336 patients were included in IP group and 320 patients in SIO group. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in rates of age, sex ratio, cirrhosis ratio, types of hepatectomy, and preoperative laboratory test, except hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA level (Table 1). Hepatitis B patients were distributed homogeneously between groups. ALT, AST, and alpha-fetoprotein were higher than normal value in both groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Clinical Characteristics of HCC Patients

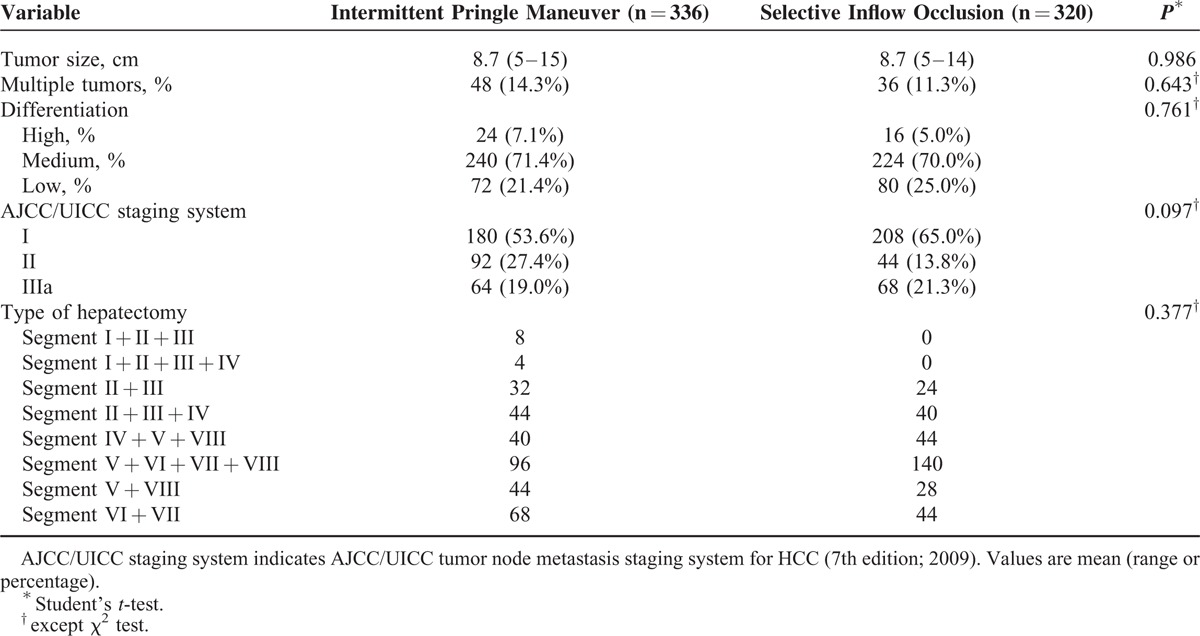

Clinicopathological Characteristics and Type of Hepatectomy

There were no significant differences between the 2 groups regarding tumor size, patients with multiple tumors, grade of tumor differentiation, and American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer staging (Table 2). More than half of the patients belonged to the medium differentiation and AJCC/UICC stage I.19 None of the patients exhibited distant metastasis. There was no significant difference in type of hepatectomy between 2 groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Pathological Factors of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Patients

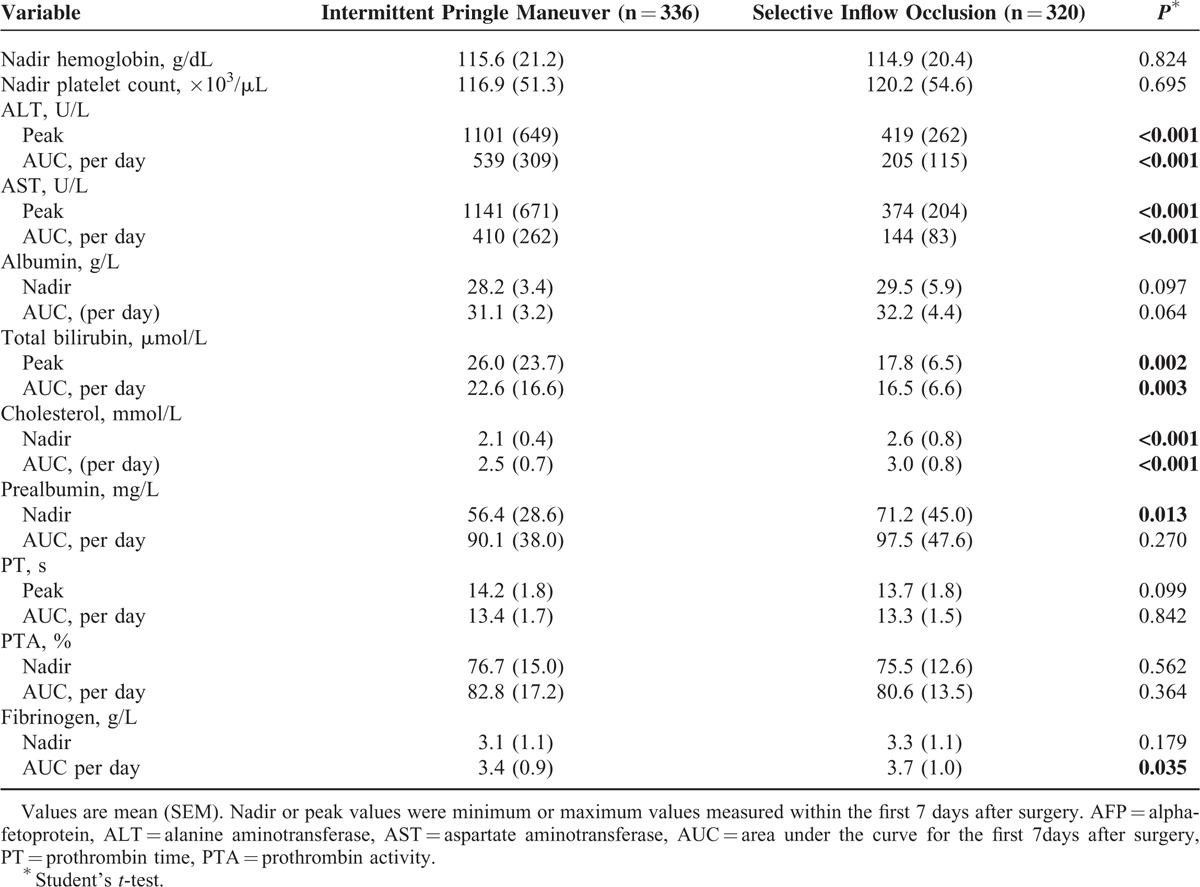

Influence of Type of Clamping on Postoperative Laboratory Test Results

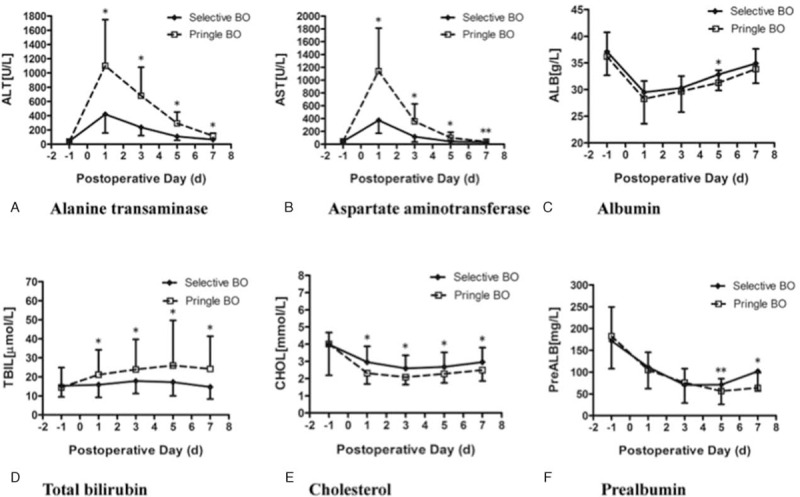

Peak values of ALT and AST occurred on the 1st day after surgery (Table 3). In most patients, AST and ALT levels returned to normal within 7 days (Figure 1). Total ALT, AST, and total bilirubin levels in IP group were significantly higher than those in SIO group, while cholesterol and fibrinogen levels in IP group were lower (Table 3). The dynamic change of transaminase, albumin, bilirubin, cholesterol, and prealbumin level on postoperative days 1, 3, 5, and 7 are shown in Figure 1. For SIO group, the cholesterol level showed an earlier increase to normal value, and the albumin level returned to baseline level on postoperative day 7. There was a significant difference in the change of prealbumin on postoperative day 5 and day 7 between 2 groups.

TABLE 3.

Postoperative Laboratory Test Results and Outcome Data

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of (A) alanine transaminase, (B) aspartate aminotransaminase, (C) albumin, (D) total bilirubin, (E) cholesterol, and (F) prealbumin in patients in new selective inflow occlusion (selective BO) and intermittent Pringle maneuver (Pringle BO) groups. Serial measurements in A–F are presented as mean (SEM). ∗P < 0.01, ∗∗P < 0.05 versus Pringle maneuver (Student's t-test).

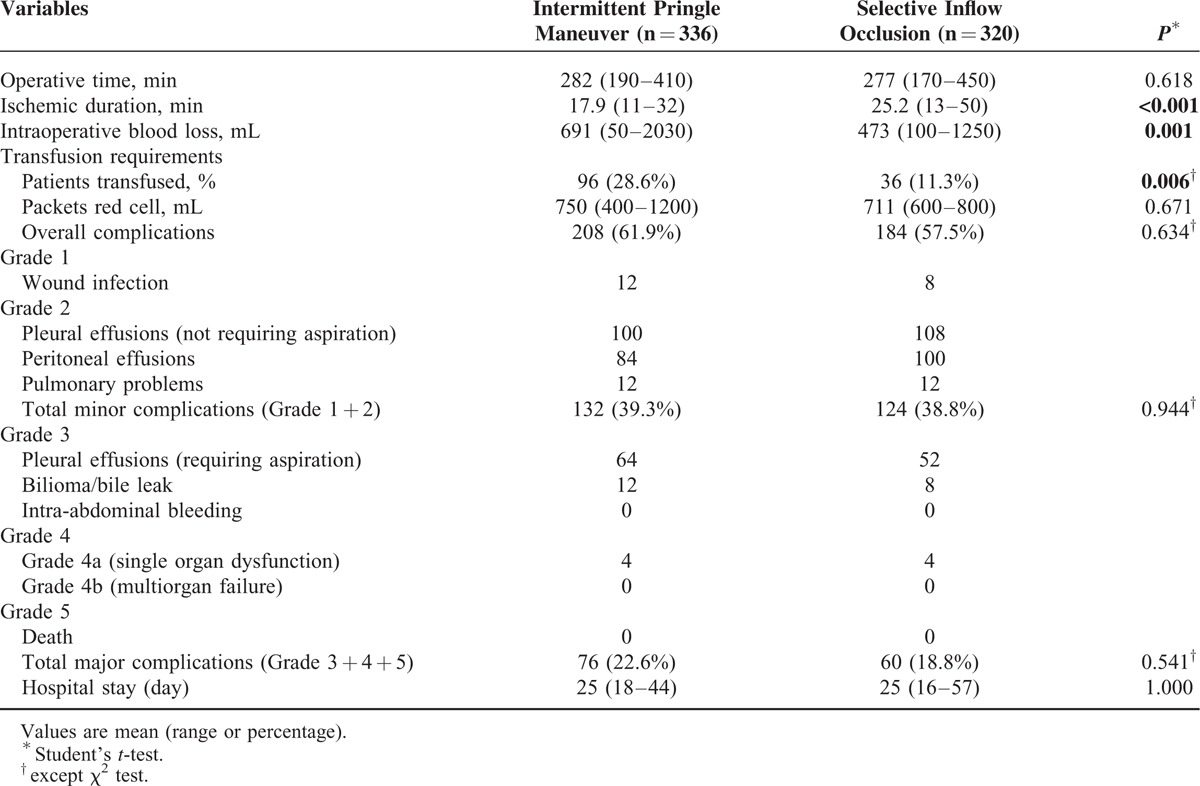

Influence of Type of Clamping on Operative Parameter

The intraoperative data including operative time, ischemic duration, intraoperative blood loss, and blood transfusion are shown in Table 4. Several patients suffered from different complications (61.9% vs 57.5%, Table 4). No patients died after the operation in any group. No patients were found to have early postoperative bleeding requiring reexploration in any of 2 groups. More than half of the patients had abdominal/subphrenic collection or pleural effusion, and only few patients suffered complications of bile leak, wound infection, or chest infection. There was no significant difference in hospital stay between 2 groups.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of Operative Parameters and Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Patients

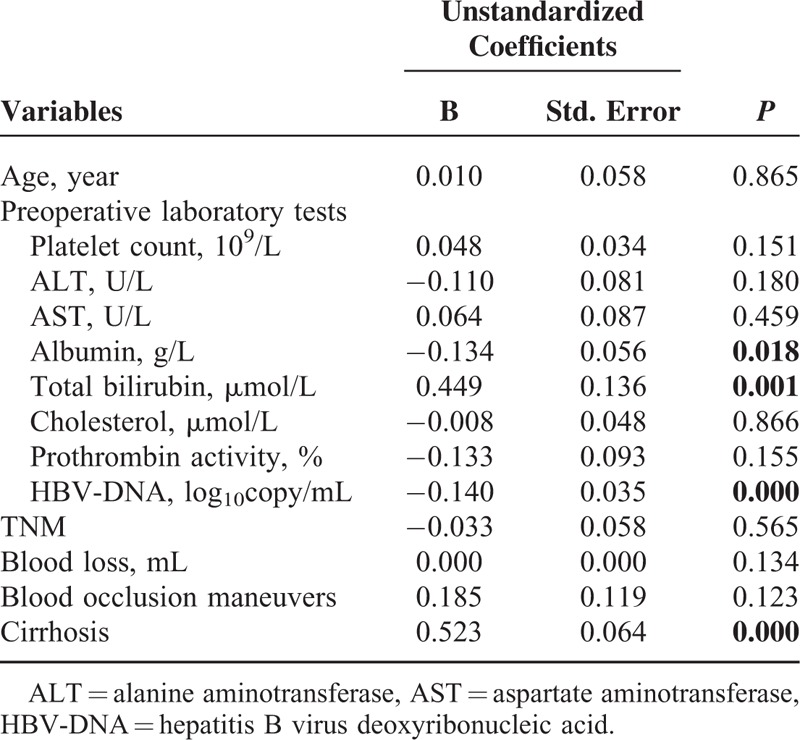

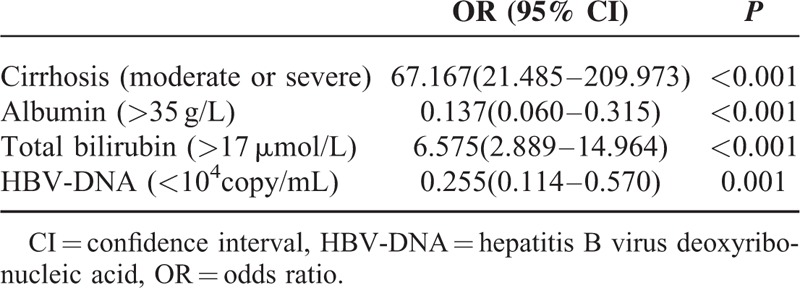

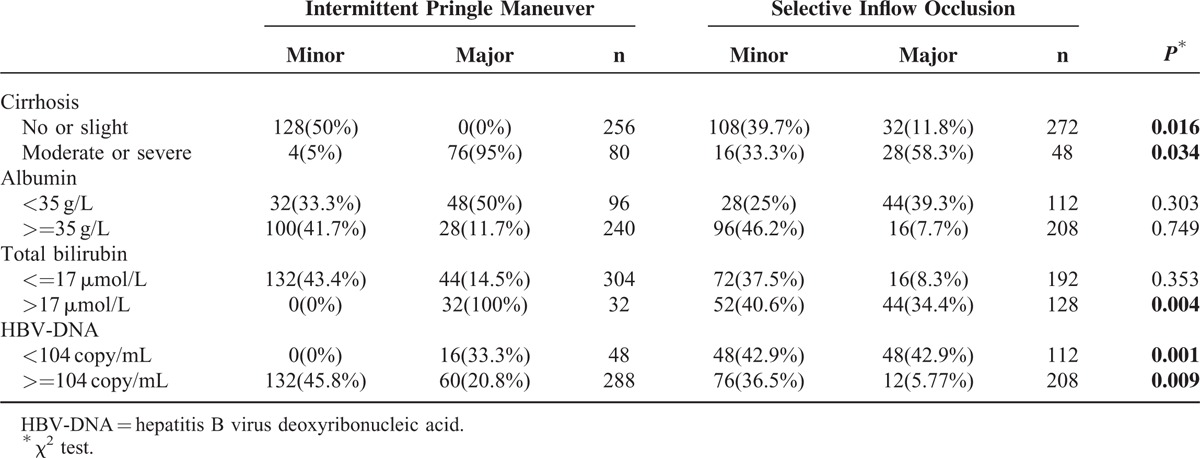

Risk Factors Related to Major Complications

Multivariate analysis confirmed that albumin, total bilirubin, HBV DNA, cirrhosis were related to postoperative complications morbidity (Table 5). The logistic regression analysis showed that 4 parameters were independent predictive factors for the development of complications (Table 6). The subgroup analysis showed that patients with moderate or severe cirrhosis, total bilirubin > 17 μmol/L, or HBV DNA> = 104 copy/mL in SIO group resulted in less major complication, when compared with the IP group (Table 7). However, the type of hepatic vascular occlusion had no influence on morbidity in albumin (<35 g/L), albumin (>=35 g/L), and total bilirubin (<=17 μmol/L) subgroups.

TABLE 5.

Risk Factors for Major Complications According to Multivariate Analysis

TABLE 6.

Risk Estimate of Factors Related With Major Complications

TABLE 7.

Comparison of Postoperative Complications According to Different Risk Factors

DISCUSSION

Excessive blood loss during hepatectomy requiring perioperative blood transfusion has a negative impact on morbidity and mortality,6,20,21 particularly in patients with cirrhosis. Using modern technology, hepatic parenchymal transection can be carried out with little blood loss. A Japanese survey revealed that only a minority (7%) of surgeons never use inflow occlusion, whereas 25% apply a Pringle maneuver on a routine basis even in cirrhotic patients.22 Although inflow occlusion is not necessarily accepted as routine practice, many surgeons still prefer to use hepatic vascular inflow occlusion with, or without outflow occlusion during parenchymal transection,3,12,23,24 especially in those cirrhotic patients with irregular branches and collateral circulations of vessels.

The Pringle maneuver is sufficient in most situations to control bleeding from the hepatic artery or portal vein during hepatectomy. However, it is hard to avoid ischemic injury in the remnant liver after Pringle maneuver and may result in postoperative liver dysfunction.3,12,15,16 The degree of ischemic injury to the hepatocytes may be accentuated in the presence of underlying liver disease.25 Therefore, several strategies have been used to minimize ischemic injury during liver surgery. Makuuchi et al26 first interrupted long ischemic intervals during liver resection with short periods of reperfusion in 1980s. Belghiti et als’27 RCT provided evidence that intermittent clamping of portal triad was superior to protect liver function when compared with continuous clamping. Thereafter, ischemic preconditioning was considered as an alternative to intermittent clamping and was proved to protect liver from injury.28 In addition, more than 80% of HCC patients suffer from HBV infection in China,3,4,10,11 which also contributes to a different degree of cirrhosis. For these patients, choosing an inflow occlusive maneuver during liver resection still warrants further study.

Since 1963, continuous selective inflow occlusion of the hepatic artery supplying the tumor-containing segments of liver plus intermittent occlusion of the portal vein has been applied to reduce blood loss and injury to the liver function.17 The main concern over the SIO maneuver is whether there is an increase in ischemic complications, especially when the occlusion is required for a long time. In the Cochrane review by Gurusamy et al,29 there was no evidence to support SIO over portal triad clamping. However, all trials in this review were of high risk of bias. Our data showed that intraoperative blood loss (473 vs 691 mL) and perioperative blood transfusion (11.3% vs 28.6%) in SIO group were significantly less than those in the IP group, although the ischemic duration was longer (25.2 vs 17.9 minutes). The difference might be caused, in part, by different parenchymal transection speed. Further the work of hemostasis may not be performed until the transection is finished. This was confirmed by results of blood loss and blood transfusion rates. Based on our data, liver function was less intensely influenced and recovered more quickly in SIO group when compared with IP group. This could be explained by less impairment of hepatic metabolism and synthesis function as a consequence of continuous arterial infusion of remnant liver in the SIO group.

In 2006, Clavien28 reported that the rate of overall and major (grade 3–5) postoperative complications with IP maneuver was 37.8% and 27%. In 2010, Fu et al23 reported that overall postoperative complication and operative mortality rates for liver resection under total hepatic vascular exclusion were 53% and 2%. In this study, only 60 patients (18.8%) with SIO maneuver suffered from major postoperative complications, and no patient died in the SIO group. Four patients with hepatic insufficiency recovered and were discharged. All of these findings confirm that the SIO maneuver is safe and well-tolerated compared with the IP maneuver and total hepatic vascular exclusion.

Multiple European-based studies6,30 have confirmed that hepatitis C virus related cirrhosis, intraoperative bleeding volume, high central venous pressure, low lactate clearance, and hepatic venous pressure gradient > 10 mmHg are the main predictor for hepatic decompensation after hepatectomy, especially in patients with liver cirrhosis. Further multivariate analyses demonstrated that initial central venous pressure higher than 9 mmHg, initial HVPG higher than 10 mmHg, and intraoperative bleeding volume were independent predictors related to postoperative morbidity.6,30,31 However, there is controversy about the clinical importance of these factors in Asian countries. For instance, most HCC patients in oriental countries are HBV-infected.3,32 As Makuuchi33 and Fan34,35 revealed, selection of candidates for liver resection relies on Child–Pugh classification and indocyanine green retention at 15 minutes retention test, while hepatic venous pressure gradient is not routinely measured and used to decide whether it is appropriate for operation or not. Therefore, we could not use these factors to evaluate the risk of postoperative complication, which is also one of the main limitations of this retrospective study. Based on our results, cirrhosis (moderate and severe), total bilirubin (>17 μmol/L), albumin (<35 g/L), and HBV DNA (>104 copy/mL) are independent predictive factors for the development of postoperative complications. Albumin not only plays an important role in maintaining the fluid balance between the intravascular and extravascular compartments,36 but can also modulate hyperinflammatory responses after surgery through scavenging free radicals and reactive inflammatory mediators in the intravascular compartment.37 Many studies38,39 have confirmed that albumin administration may improve outcomes with respect to morbidity and mortality in liver disease or hypoalbuminemia patients. So, we routinely recommend the administration of 20% albumin to correct serum levels up to 30 g/L during perioperative period.

As we know, each hepatic vascular occlusion technique has its place in liver surgery. Tumor location, underlying liver disease, the experience of the surgical, and anesthetic team should be taken into account to select the appropriate method for achieving hepatic vascular control in a given patient. Based on the findings of this study, we recommend that the SIO maneuver has superiority over the IP maneuver in terms of parenchymal tolerance to ischemia for patients with moderate or severe cirrhosis, total bilirubin > 17 μmol/L, or HBV DNA >=104 copy/mL, if needed. Recent study32 confirmed that partial hepatectomy for HBV-related HCC induced HBV reactivation in a proportion of patients. We recommend antiviral therapy for those patients with HBV DNA more than 500 copy/mL and close monitoring with HBV DNA in the perioperative period for all patients with HBV-related HCC.

As far as the limitation is concerned, it is a retrospective study with limited number of patients in a single center. Risk of bias still existed, although it was performed in a consecutively manner. A randomized clinical trial with larger number of patients would provide stronger evidence to get a conclusion.

One of the potential drawbacks of applying selective inflow occlusion is to perform a porta hepatic dissection, although it is not difficult for experienced surgeons. When the tumor has infiltrated porta hepatis or major vessels in the hepato-duodenal ligament, it is contraindicated to apply this maneuver. The other limitation is that all conclusions from this retrospective study should be further confirmed by several prospective randomized studies with higher grade evidence.

In view of our results, we can conclude that the SIO maneuver is safe and effective. SIO has less impairment of hepatic function compared with IP. Cirrhosis (moderate or severe), total bilirubin (>17 μmol/L), albumin (<35 g/L), and HBV DNA (>104 copy/mL) are independent predictive factors for morbidity. For patients with moderate or severe cirrhosis, total bilirubin > 17 μmol/L, or HBV DNA >=104 copy/mL, SIO maneuver is preferentially recommended. We think that these conclusions may help hepato-biliary surgeons decide which maneuver to choose during hepatectomy, if occlusion is necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Chinese Ministry of Public Health for Key Clinical Projects (No. 2012ZX10002016) and Hubei Province for the Clinical Medicine Research Centre of Hepatic Surgery (2007) for the support. The authors also thank Dr Dengping Ying from Chicago University for language assistance.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ALT = alanine aminotransferase, AST = aspartate amino transferase, HBV = hepatitis B virus, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, HCV = hepatitis C virus, IP = intermittent Pringle maneuver, PT = prothrombin time, SIO = selective inflow occlusion maneuver.

PZ, BZ, and RW contributed equally to this work.

This study was supported by grants from the Chinese Ministry of Public Health for Key Clinical Projects (No. 2012ZX10002016) and Hubei Province for the Clinical Medicine Research Centre of Hepatic Surgery (2007).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2007; 132:2557–2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arii S, Yamaoka Y, Futagawa S, et al. Results of surgical and nonsurgical treatment for small-sized hepatocellular carcinomas: a retrospective and nationwide survey in Japan. The Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Hepatology 2000; 32:1224–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu P, Lau WY, Chen YF, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing infrahepatic inferior vena cava clamping with low central venous pressure in complex liver resections involving the Pringle manoeuvre. Br J Surg 2012; 99:781–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen XP, Qiu FZ, Wu ZD, et al. Chinese experience with hepatectomy for huge hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 2004; 91:322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kooby DA, Stockman J, Ben-Porat L, et al. Influence of transfusions on perioperative and long-term outcome in patients following hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg 2003; 237:860–869.discussion 869–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, et al. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1,803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg 2002; 236:397–406.discussion 406–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiba H, Ishida Y, Wakiyama S, et al. Negative impact of blood transfusion on recurrence and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13:1636–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon AH, Matsui Y, Kamiyama Y. Perioperative blood transfusion in hepatocellular carcinomas: influence of immunologic profile and recurrence free survival. Cancer 2001; 91:771–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto J, Kosuge T, Takayama T, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion promotes recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Surgery 1994; 115:303–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen XP, Qiu FZ. A simple technique ligating the corresponding inflow and outflow vessels during anatomical left hepatectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008; 393:227–230.discussion 231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen XP, Zhang ZW, Zhang BX, et al. Modified technique of hepatic vascular exclusion: effect on blood loss during complex mesohepatectomy in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with cirrhosis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2006; 391:209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu SY, Lau WY, Li GG, et al. A prospective randomized controlled trial to compare Pringle maneuver, hemihepatic vascular inflow occlusion, and main portal vein inflow occlusion in partial hepatectomy. Am J Surg 2011; 201:62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malassagne B, Cherqui D, Alon R, et al. Safety of selective vascular clamping for major hepatectomies. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 187:482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau WY. A review on the operative techniques in liver resection. Chin Med J (Engl) 1997; 110:567–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selzner N, Rudiger H, Graf R, et al. Protective strategies against ischemic injury of the liver. Gastroenterology 2003; 125:917–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serracino-Inglott F, Habib NA, Mathie RT. Hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Surg 2001; 181:160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia S. An approach to the typical liver resection. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol 1984; 13:384–387. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004; 240:205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahbari NN, Mehrabi A, Mollberg NM, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: current management and perspectives for the future. Ann Surg 2011; 253:453–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahbari NN, Koch M, Mehrabi A, et al. Portal triad clamping versus vascular exclusion for vascular control during hepatic resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13:558–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smyrniotis V, Farantos C, Kostopanagiotou G, et al. Vascular control during hepatectomy: review of methods and results. World J Surg 2005; 29:1384–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakajima Y, Shimamura T, Kamiyama T, et al. Control of intraoperative bleeding during liver resection: analysis of a questionnaire sent to 231 Japanese hospitals. Surg Today 2002; 32:48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu SY, Lau WY, Li AJ, et al. Liver resection under total vascular exclusion with or without preceding Pringle manoeuvre. Br J Surg 2010; 97:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Lai EC, Zhou WP, et al. Selective hepatic vascular exclusion versus Pringle manoeuvre in liver resection for tumours encroaching on major hepatic veins. Br J Surg 2012; 99:973–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grace PA. Ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Br J Surg 1994; 81:637–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makuuchi M, Mori T, Gunven P, et al. Safety of hemihepatic vascular occlusion during resection of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1987; 164:155–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belghiti J, Noun R, Malafosse R, et al. Continuous versus intermittent portal triad clamping for liver resection: a controlled study. Ann Surg 1999; 229:369–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrowsky H, McCormack L, Trujillo M, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing intermittent portal triad clamping versus ischemic preconditioning with continuous clamping for major liver resection. Ann Surg 2006; 244:921–928.discussion 928–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurusamy KS, Sheth H, Kumar Y, et al. Methods of vascular occlusion for elective liver resections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; CD007632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruix J, Castells A, Bosch J, et al. Surgical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: prognostic value of preoperative portal pressure. Gastroenterology 1996; 111:1018–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melendez JA, Arslan V, Fischer ME, et al. Perioperative outcomes of major hepatic resections under low central venous pressure anesthesia: blood loss, blood transfusion, and the risk of postoperative renal dysfunction. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 187:620–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang G, Lai EC, Lau WY, et al. Posthepatectomy HBV reactivation in hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma influences postoperative survival in patients with preoperative low HBV-DNA levels. Ann Surg 2013; 257:490–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orii R, Sugawara Y, Hayashida M, et al. Effects of amrinone on ischaemia-reperfusion injury in cirrhotic patients undergoing hepatectomy: a comparative study with prostaglandin E1. Br J Anaesth 2000; 85:389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan ST, Mau Lo C, Poon RT, et al. Continuous improvement of survival outcomes of resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 20-year experience. Ann Surg 2011; 253:745–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, et al. Hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: toward zero hospital deaths. Ann Surg 1999; 229:322–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang J, Wang WT, Yan LN, et al. Alternatives to albumin administration in hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing hepatectomy: an open, randomized clinical trial of efficacy and safety. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011; 124:1458–1464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiedermann CJ. Colloidal and pharmacological activity of albumin in clinical fluid management: recent developments. Curr Drug Ther 2006; 1:319–328. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vincent JL, Dubois MJ, Navickis RJ, et al. Hypoalbuminemia in acute illness: is there a rationale for intervention? A meta-analysis of cohort studies and controlled trials. Ann Surg 2003; 237:319–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haynes GR, Navickis RJ, Wilkes MM. Albumin administration – what is the evidence of clinical benefit? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2003; 20:771–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]