Abstract

Background:

Biotin–thiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease (BTRBGD) is a neurometabolic autosomal recessive (AR) disorder characterized by subacute encephalopathy with confusion, convulsions, dysarthria, and dystonia. The disease is completely reversible if treated early with biotin and thiamine, and can be fatal if left untreated.

We herein present our experience with in an extended family study of an index case of BTRBGD aiming to support its AR mode of inheritance, diagnose asymptomatic and missed symptomatic cases, and provide family screening with proper genetic counseling.

Methods:

An index case of BTRBGD and his family underwent thorough clinical and radiological assessment along with genetic molecular testing.

Results:

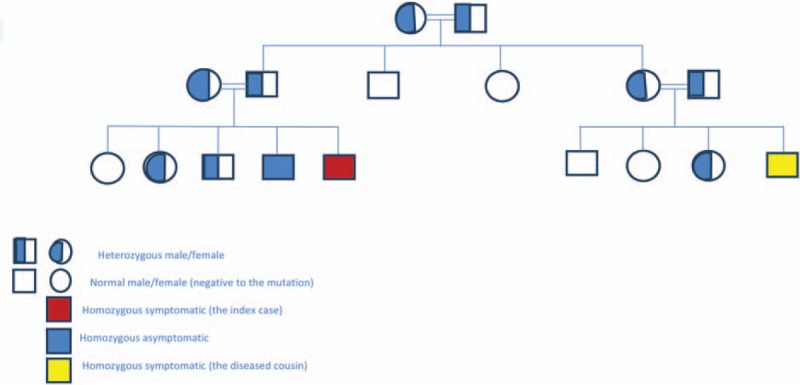

Two-and-half years old Saudi male child whose parents are consanguineous fulfilled the clinical and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) criteria of BTRBGD. He was proved by molecular genetic testing to have homozygous mutation of c.1264A>G (p.Thr422Ala) in the SLC19A3 gene of BTRBGD. Extended clinical, radiological, and genetic family study revealed 2 affected members: a neglected symptomatic cousin with subtle neurological affection and an asymptomatic brother carrying the disease mutation in homozygous status. Heterozygous pattern was detected in his parents, his grandma and grandpa, his aunt and her husband, 2 siblings, and 1 cousin while 1 sibling and 2 cousins were negative to this mutation.

Treatment of the patient and his diseased cousin with biotin and thiamine was initiated with gradual improvement of symptoms within few days. Treatment of his asymptomatic brother was also initiated.

Conclusion:

BTRBGD requires high index of suspicion in any child presenting with unexplained subacute encephalopathy, abnormal movement, and characteristic MRI findings. Extended family study is crucial to diagnose asymptomatic diseased cases and those with subtle neurological symptoms.

Keywords: biotin, biotin–thiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease, encephalopathy, neurometabolic, SLC19A3, thiamine

1. Introduction

Biotin–thiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease (BTRBGD) (OMIM: 607483) is inherited in autosomal recessive manner. Some researchers named it as thiamine metabolism dysfunction syndrome-2. It is a neurometabolic syndrome which was first described on 1988.[1]

The disease usually presents in childhood and is characterized by 3 stages: stage 1: subacute encephalopathy which usually follows fever with development of vomiting and confusion; stage 2: acute encephalopathy, with seizures, loss of motor functions (quadriparesis or quadriplegia), loss of developmental milestones, dysphagia, and dysarthria; and stage 3: chronic or slowly progressive encephalopathy, with an akinetic mute state, permanent loss of speech and comprehension, and eventual death.[2] Four different phenotypes have been described; infantile lactic acidosis with encephalopathy,[3] infantile epileptic spasms,[4] early childhood encephalopathy triggered by illness or trauma,[2] and Wernicke-like encephalopathy in the second decade.[5]

The diagnosis needs high index of suspicion based on history, neurologic signs, and consistent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of abnormal signal hyperintensity of the caudate and putamen, diffuse brain involvement with cortical and subcortical white matter, and the infratentorial regions with less frequent involvement of the thalami, brain stem, cerebellum, and cervical spine.[1,2,6,7]

These MRI findings do resemble findings of Leigh disease or of Gayet-Wernicke encephalopathy that is why BTRBGD can be misdiagnosed as a mitochondrial disease due to similarities in clinical, biochemical, and MRI findings.[8]

Although of this devastating picture, the good thing is that early administration of high doses of biotin and thiamine can ameliorate the symptoms of BTRBGD within few days, with no recurrence unless treatment is discontinued but delayed treatment usually leaves residual paraparesis, mild mental retardation, or dystonia.[9]

Recently, this disease became under focus in our country; Saudi Arabia; as most of the reported cases are Saudi.[1,2,8]

We herein present our experience with BTRBGD from a single center from Saudi Arabia. Our report is the 1st to use the strategy of extended genetic family screening which proved ultimate success in diagnosing asymptomatic and subtle cases where treatment was provided before disease become overt as it is well known that once disease became overt, no one can guarantee its long-term sequels.

2. Case report

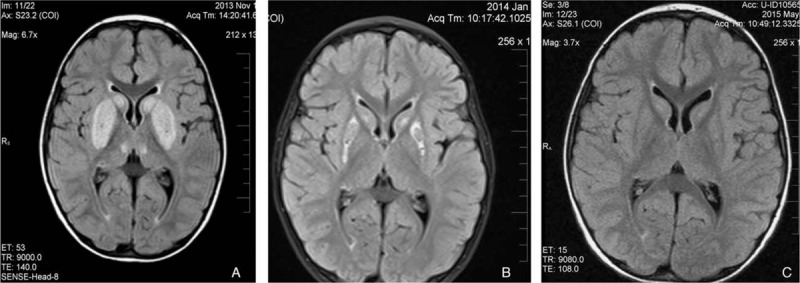

A 2.5-year-old male Saudi child presented with sudden onset of ataxia and left-sided dystonic posturing of all limbs of 1 day duration which was preceded by a history of runny nose and cough for several days but no history of fever, vomiting, abnormal movement, or skin rash. There was no history of any drug intake or herbal medications. The patient was fully alert but with hypertonia and hyperreflexia of all his limbs especially on the left side. He was able to walk with support with ataxic gait. Other systemic examination was unremarkable. The parents were consanguineous and other siblings were apparently healthy. MRI brain of the patient showed basal ganglia changes consistent with BTRBGD (Fig. 1A). Molecular genetic analysis and screening of the family for SLC19A3 mutation was carried on. The 5 coding exons and the exon–intron boundaries of SLC19A3 gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction and analyzed by direct sequencing which revealed at position c.1264 in exon 5 of the SLC19A3 gene the nucleotide exchange (c.1264A>G), resulting in a substitution of the evolutionarily highly conserved threonine to alanine at position 422 of the protein sequence (p.Thr422Ala) in homozygous state in the patient, one of his cousins, and an asymptomatic brother (Fig. 2). Heterozygous pattern was detected in his parents, his grandma and grandpa, his aunt and her husband, 2 siblings, and 1 cousin while 1 aunt, 1 uncle, 1 sibling, and 2 cousins were negative to this mutation (Fig. 2). Brain MRI screening of the whole family was normal in those with heterozygous state and had characteristic picture of BTRBGD in those with homozygous state even if asymptomatic.

Figure 1.

(A) Abnormal signal intensity due to necrosis of the caudate and putamen, diffuse brain involvement with cortical and subcortical white matter, and the infratentorial regions; (B) partial improvement at 2 months of treatment; (C) complete resolution at 6 months of treatment.

Figure 2.

Pedigree of the extended family of the index case.

Meeting was held with the family for genetic counseling. Reinforcement on them about any neurological disease within the family, revealed 1 cousin who died undiagnosed with similar neurological condition; encephalopathy and convulsions. That was initially denied and hided by the family.

The patient, his symptomatic cousin, and asymptomatic brother were started on biotin 2 mg/kg in 2 divided doses and thiamine 100 mg/8 h. Improvement was slow in symtomatic patients, so thiamine dose was increased to 200 mg/8 h after a week of treatment initiation, that was followed by very good improvement. The dystonic posture was the first to improve with normalization of the tone and reflexes, followed by improvement of the gait and then he regained his full ability to run at 2 weeks of treatment increment. Lifelong treatment and regular follow-up at neurology clinic were decided.

Follow-up of the patient at 2 and 6 months revealed completely normal neurological examination with partial (Fig. 1B) then complete (Fig. 1C) resolution of MRI abnormalities, respectively. Thiamine was decreased to 100 mg/8 h with instructions to double the dose during periods of infections and stress which are associated with high energy demands and so more need for thiamine.

3. Discussion

BTRBGD is an autosomal recessive disorder which was first described in 1998. Interestingly enough that the 1st report about disease included 10 children, 8 of them were Saudi.[2] On 2013, 10 more Saudi children were reported by Tabarki and his group.[8] In the same year, Alfadel et al reported the largest series from Saudi Arabia which included 18 patients.[1]

The disease was also reported from Syria, Yemen, Morocco, Europe (Portugal and Spain), Canada, India, Japan, Lebanon, and other ethnic groups (Pan ethnic).[1,5,6,10,11]

The disease locus was mapped on 2q36.3 with 2 missense mutations dentified in the SLC19A3 gene.[9]

Genetic testing of the whole family added more to the confirmation of its autosomal recessive mode of inheritance.

Early diagnosis and treatment is pivotal for favorable outcome. SLC19A3 gene encodes hTHTR2, a second thiamine-transporter and not a biotin transporter.[9] In fact, hTHTR2 demonstrates 48% structural identity to hTHTR1, which is also a thiamine transporter, while demonstrating only 17% identity with hSMVT, which is a known biotin transporter.[9] This evidence supports the importance of thiamine in the treatment of this disease but leaves the mechanism by which biotin acts, unclear. However, it could be hypothesized that the biotin and thiamine transporters in the basal ganglia are closely associated and thus act synergistically.[8] Therefore, we recommend that the treatment regimen for patients with BTRBGD must contain both thiamine and biotin.

Administration of high doses of thiamine is essential as it probably well bypasses the defective thiamine transporting protein[9] and restore insufficient thiamine transport by overexpression of SLC19A3 gene.[10] Most researchers used thiamine of 100 to 300 mg/d and biotin (2–10 mg/kg per d)[2,5,8] as treatment with biotin alone, showed no improvement in 30% of patients.[6] Using both thiamine and biotin, lead to good improvement and maintain good metabolic control for 6 months after biotin was discontinued.[3] Some researchers used lower dose of thiamine (10 mg/kg per d) and further decreased it overtime[12] but that was likely not enough to sustain clinical improvement, it may only have contributed to longer life span.

We believed that thiamine is the most crucial that is why we used high dose of 600 mg/d at initiation of treatment and during periods of stress as a dose of 300 mg/d was not sufficient to induce remission in our patients. Biotin was used at a dose of 2 mg/kg per day all through to benefit from its synergistic effect. Thiamine was decreased to 300 mg/d after improvement and continued to maintain remission. We plan to keep patients on the lowest maintenance doses which can keep remission.

Due to the relatively high number of BTRBGD patients in Saudi Arabia, a Saudi multicenter center study is underplanning to study the special peculiarities of the Saudi patients, their demographics, disease characteristics, disease severity, and different treatment, and maintenance regimens.

The outcome of our report with early diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic patients had led us to suggest adding another arm to the Saudi multicenter study using extended molecular testing of families of index cases for proper characterization of our country genetic mutations along with identifying homozygous cases who are asymptomatic or having subtle symptoms aiming for prevention of overt disease rather than waiting it until it became symptomatic.

4. Conclusions

BTRBGD is a relatively missed disease which needs to be put in the differential diagnosis of any patient presenting with encephalopathy, convulsions, and deteriorating neurological functions especially in countries with relatively high number of cases like Saudi Arabia.

The disease is reversible if treatment started promptly. Biotin and high doses of thiamine are the mainstay of treatment.

We recommend a national program to screen high-risk tribes so that presymptomatic treatment could be started to prevent much of the morbidity and mortality. This approach if adopted will also serve to increase the awareness among vulnerable population for premarital testing and well in the long way limits the prevalence of the condition.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AR = autosomal recessive, BTRBGD = biotin–thiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

The study was approved by the research and ethical committee of Alhada Armed Forces Hospital, Taif, Saudi Arabia. Written informed consents were obtained from all the contributing family members or their guardians.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Alfadhel M, Almuntashri M, Jadah RH, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease should be renamed biotin-thiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease: a retrospective review of the clinical, radiological and molecular findings of 18 new cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013; 8:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozand PT, Gascon GG, Al Essa M, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease: a novel entity. Brain 1998; 121:1267–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez-Duenas B, Serrano M, Rebollo M, et al. Reversible lactic acidosis in a newborn with thiamine transporter-2 deficiency. Pediatrics 2013; 131:e1670–e1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamada K, Miura K, Hara K, et al. A wide spectrum of clinical and brain MRI findings in patients with SLC19A3 mutations. BMC Med Genet 2010; 11:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kono S, Miyajima H, Yoshida K, et al. Mutations in a thiamine-transporter gene and Wernicke's-like encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:1792–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kevelam SH, Bugiani M, Salomons GS, et al. Exome sequencing reveals mutated SLC19A3 in patients with an early-infantile, lethal encephalopathy. Brain 2013; 136:1534–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Debs R. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease in ethnic Europeans with novel SLC19A3 mutations BBGD in ethnic Europeans with SCL19A3 mutations. Arch Neurol 2010; 67:126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabarki B, Al-Shafi S, Al-Shahwan S, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease revisited: clinical, radiologic, and genetic findings. Neurology 2013; 80:261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng WQ, Al-Yamani E, Acierno JS, Jr, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease maps to 2q36.3 and is due to mutations in SLC19A3. Am J Hum Genet 2005; 77:16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerards M, Kamps R, van Oevelen J, et al. Exome sequencing reveals a novel Moroccan founder mutation in SLC19A3 as a new cause of early-childhood fatal Leigh syndrome. Brain 2013; 136:882–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serrano M, Rebollo M, Depienne C, et al. Reversible generalized dystonia and encephalopathy from thiamine transporter 2 deficiency. Mov Disord 2012; 27:1295–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sremba LJ, Chang RC, Elbalalesy NM, et al. Whole exome sequencing reveals compound heterozygous mutations in SLC19A3 causing biotin-thiamine responsive basal ganglia disease. Mol Genet Metab Reports 2014; 1:368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]