Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency, common variable immunodeficiency, ectodermal dysplasia, NFKB2 protein

Abstract

Background

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) with central adrenal insufficiency is a recently defined clinical syndrome caused by mutations in the nuclear factor kappa-B subunit 2 (NFKB2) gene. We present the first case of NFKB2 mutation in Asian population.

Methods and Results

An 18-year-old Chinese female with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) deficiency was admitted due to adrenal crisis and pneumonia. She had a history of recurrent respiratory infections since childhood and ectodermal abnormalities were noted during physical examination. Immunologic tests revealed panhypogammaglobulinemia and deficient natural killer (NK)-cell function. DNA sequencing of NFKB2 identified a heterozygous nonsense mutation (c.2563 A>T, p.855: Lys>∗) in the patient but not her parents.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be alert to comorbidities of adrenal insufficiency and ectodermal dysplasia in CVID patients as these might suggest a rare hereditary syndrome caused by NFKB2 mutation.

1. Introduction

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is characterized by primary hypogammaglobulinemia, and in consequence increased susceptibility to infections. Recently, a hereditary form of CVID (MIM 615577) presented with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) deficiency, and less frequently ectodermal abnormalities, has been reported.[1] This rare autosomal dominant disorder has been associated with mutations in nuclear factor kappa-B subunit 2 gene (NFKB2, MIM 164012).[1–6]

NFKB2 belongs to the NF-κB family, which consists a collection of evolution-conserved transcription factors involved primarily in development, immunity, and oncogenesis.[7] Mutations in genes encoding either NF-κB transcription factors or their regulators have been associated with primary immunodeficiency and autoimmunity.[8]

Human NFKB2 encodes the full-length p100 protein, which serves both as an inhibitor of the canonical NF-κB signaling and a central player of the noncanonical pathway. In the latter, certain receptor signals activate IκB kinase α (IKKα)-mediated phosphorylation of 2 serine residues (Ser866, Ser870) near the C-terminus of p100, leading to its partial proteolysis to the active form p52.[7] Mutations identified in CVID with central adrenal insufficiency involve 1 or both of these 2 serine residues, disrupting this critical pathway in lymphoid organogenesis, B-cell survival and maturation, and dendritic cell activation.[9]

To date, 8 mutations in NFKB2 have been recognized in 10 families.[1–6] We hereby report a heterozygous nonsense NFKB2 mutation in a Chinese patient, with descriptions of her clinical features.

2. Case presentation

2.1. Clinical characterization

The patient is an 18-year-old Han female admitted to Peking Union Medical College Hospital due to adrenal crisis triggered by pneumonia. She has developed recurrent respiratory infections since age 5, and failed to respond to multiple hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccinations. Reduced serum cortisol and ACTH levels were discovered at 16 when glucocorticoid replacement was initiated. In addition, hair loss started from age 4, and absence of pubic and axillary hair was noticed after development of regular menstruation. Her history includes nephrotic syndrome, which was confirmed to be minimal change nephropathy by renal biopsy.

Physical examination at admission revealed alopecia totalis, oral candidiasis, hypohidrosis, and trachyonychia. Facial or dental abnormalities was not noted. She is the only child in her family. Symptom and signs of the above disorders were not identified among her nonconsanguineous parents.

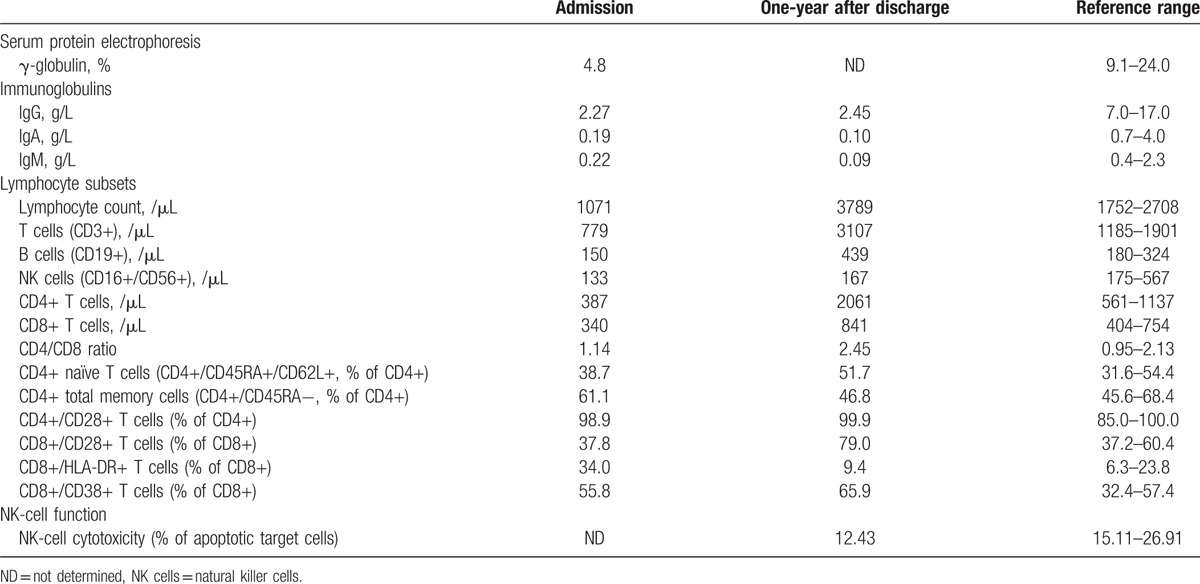

Initial immunologic tests revealed remarkable panhypogammaglobulinemia and reduced cell counts of B cells, T cells, and natural killer (NK) cells (Table 1). CD4/CD8 ratio, as well as expression levels of various T-cell activation markers were in normal range, except increased proportion of CD8+/HLA-DR+ subset. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) were negative. When regular hydrocortisone replacement was suspended, her 8:00 am serum cortisol was measured at 0.93 μg/dL, with ACTH <5.00 pg/mL. Serum levels of other anterior pituitary hormones, as well as serum and urine osmolality were within reference range. Both antiperoxidase antibody and antithyroglobulin antibody were negative. She had positive antiprotein tyrosine phosphatase antibody, with fasting blood glucose at 5.9 mmol/L. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast suggested a normal pituitary.

Table 1.

Immunologic findings.

She was diagnosed with CVID, isolated ACTH deficiency, and ectodermal dysplasia. Symptoms of fever, cough, and vomiting cleared with antibiotics and stress-dose hydrocortisone treatment. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy was suggested but denied by the parents. At follow-up 1 year after her discharge, she reported no infection events during the previous year as she stayed at home and avoided outdoor activities. Her glucocorticoid replacement was withdrawn 4 months after discharge, and she has only received traditional Chinese medicine ever since. Lymphocyte subsets test done at the follow-up documented increased levels of B cells and T cells, while NK cell count remained below normal limit. To assess her NK-cell activity, a flow cytometric procedure was done following previously described method.[10,11] Effector to target cell ratio was set at 10:1. Less apoptosis of target cell line (12.43%, reference range 15.11–26.91%) was observed when cocultured with patient's peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), indicating a deficient NK-cell cytotoxicity.

2.2. Genetic analysis

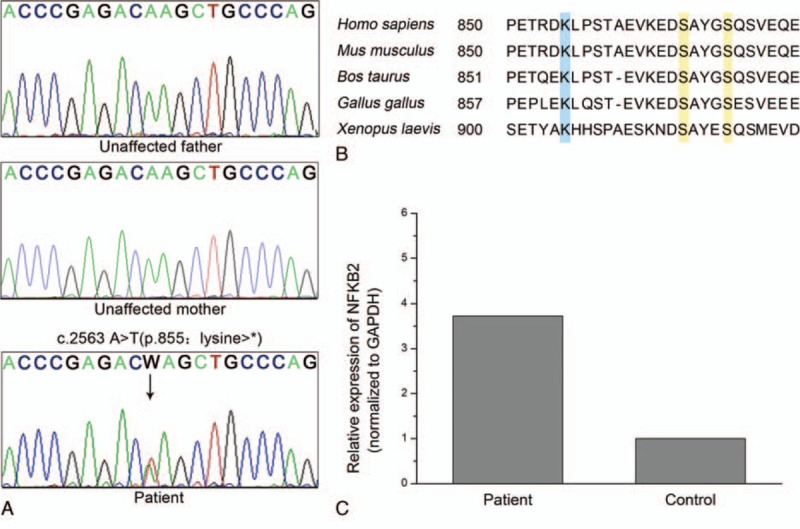

The study was approved by the ethics committee of our college. Informed consent was obtained from the patient and her parents. All exons of NFKB2 were polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified with DNA extracted from peripheral blood (see Table, Supplement Content, in which sequence of all primer pairs used are listed). PCR products were determined with an ABI 3170xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). A heterozygous nonsense mutation (c.2563 A>T, p.855: Lys>∗) was identified in exon 22 of NFKB2 in the patient, but not her parents (Fig. 1A). Variation at this position has not been previously identified in medical literature, the Exome Aggregation Consortium (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/), or the 1000 genomes (http://www.1000genomes.org/) database. Alignments of NF-κB p100 sequences among different species indicate the p.855: Lys>∗ mutation leads to loss of an evolutionary conserved segment (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

A novel NFKB2 mutation and NF-κB sequence alignments. (A) Sanger sequencing revealed a heterozygous c.2563 A>T (p.855: Lys>∗) mutation (arrow) in NFKB2 gene of the proband. This variation was not identified in her parents. (B) NF-κB p100 C-terminus amino acid sequence alignments. Lysine 855, highlighted in blue, serves as an acceptor for ubiquitination. Serine 866 and 870, highlighted in yellow, are phosphorylation sites that lead to proteolysis. (C) NFKB2 transcripts in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from proband and a healthy control were quantified by real-time PCR.

To determine NFKB2 expression level, total RNA was isolated from PBMC of the patient and a healthy control matched by age and gender. cDNA was synthesized with GoScript Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Real-time PCR was performed in triplicate using Power SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) on a ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Amplicon for NFKB2 transcript was designed upstream of the mutation site to include both wild-type and mutant transcription products. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as reference control. Data analyzed with

|

method resulted in a relative expression ratio of 3.73 (Fig. 1C).

3. Discussion

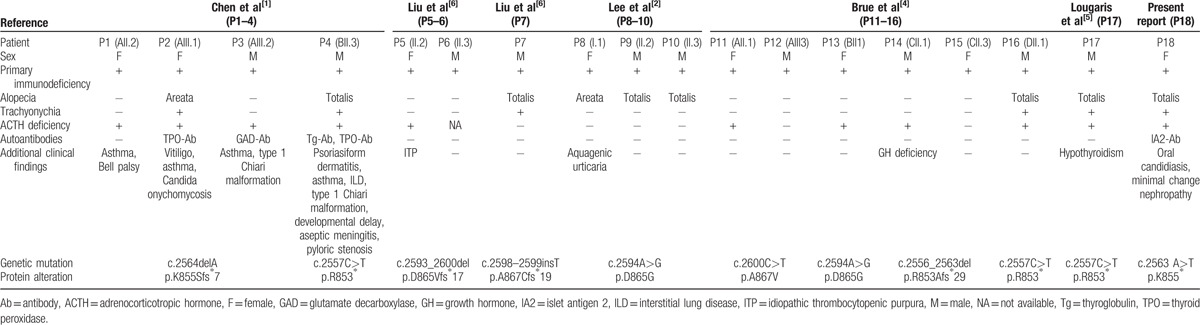

Certain forms of primary immunodeficiency accompanied by ectodermal dysplasia (MIM 612132, 300291) have been associated with mutations in the nuclear factor-kappa-B inhibitor alpha (NFKBIA) and nuclear factor kappa-B essential modulator (NEMO) genes, both encoding upstream regulators in the NF-κB canonical pathway.[12,13] Distinct from these previously identified syndromes, most patients carrying NFKB2 mutation demonstrate additional endocrinopathies (summarized in Table 2). Secondary hypoadrenalism was diagnosed in 11/18 (61.1%) of these individuals, while hypothyroidism and growth hormone deficiency were also reported. This is consistent with the fact that various autoantibodies against endocrine organs were present in the peripheral circulation of these patients. In addition, ectodermal abnormalities, together with other autoimmune disorders (i.e., vitiligo, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura) were also reported in several cases, supporting an autoimmune background for the NFKB2 mutant individuals.

Table 2.

Reported cases with NFKB2 mutation.

Interestingly, all of the mutations reported alter amino acid sequence near the C-terminus of p100, a region essential for the NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) mediated p100 processing.[12] In the noncanonical NF-κB signaling pathway, 2 conserved serine residues (Ser866, Ser870) within this NIK-responsive domain are phosphorylated after activation of IKKα induced by NIK. The phosphorylated serines in turn assemble the SCFβTrCP ubiquitin ligase.[13] Lysine (Lys) 855 upstream to these serines serves as the ubiquitin-anchoring site, and substitution of Lys855 with arginine resulted in attenuation of p100 uniquitination in both in vitro and in vivo studies.[14] It is therefore reasonable to hypothesize that the p.855: Lys>∗ mutation identified in our patient would generate a truncated form of p100 unprocessable to the active form p52. A 4-fold increase in NFKB2 expression in patient's PBMC compared with control excludes a prominent process of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, and further supports a blocked NF-κB pathway. Indeed, B cells from individuals carrying similar p.Lys855Serfs∗7 and p.Arg853∗ mutations had significant lower phosphorylated p100 and p52 levels, with reduced nuclear translocation of p52 after noncanonical signal exposure.[1]

The critical role of noncanonical NF-κB pathway in lymphoid organ development, B cell maturation, and survival has been well-established in rodents.[15] Mice carrying homozygous nonsense mutation within Nfkb2 NIK-responsive domain (Nfkb2Lym1/Lym1; c.2854A>T; p.Tyr868∗) are characterized by reduced fertility, disruptions to lymph node and spleen development, and significantly reduced mature recirculating B cells.[16] Consistent with this, reduced switched memory B cell counts, arrest in early B-cell ontogeny, as well as hypogammaglobulinemia, were observed in patients carrying NFKB2 mutation.[1,2] In our patient, all three isotypes of immunoglobulins remained below normal, while total B-cell count fluctuated during observation. Preserved B-cell counts were also noted in 5 of 14 previously reported NFKB2-mutant individuals with data available,[1–6] suggesting B-cell function, rather than its count, plays a central role in pathogenesis of immunodeficiency in these patients.

Aside from the B cell deficiency, impaired T-cell and NK-cell functions have also been reported in other NFKB2 mutant patients.[3,5] In our patient, we have observed only a transient numerical defect in T cells. Proportions for naïve and memory cells, as well as expression of activation markers, are generally within normal range. Persistent reduction in NK cell count, however, called for attention and a flow cytometric assay revealed defective NK-cell cytotoxicity. Our result supports previously described defect in NK-cell cytotoxic activity measured by 51Cr release assay,[5] although the defect in our patient seemed far milder. Similar NK cell cytotoxicity impairment was described in patients with NEMO mutations,[17] but the exact mechanism of how truncated p100 disturbs NK-cell function requires further investigation, as no short-term effect on p100 processing was detected after various stimulations on NK cell lines.[18]

Compared to the intensively studied correlation between NFKB2 mutation and immunodeficiency, less is known about pathogenesis of ACTH deficiency in these patients. In general, autoimmunity is considered as the primary underlying mechanism for isolated ACTH deficiency in adults,[19] and previous pathologic studies revealed no pituitary developmental defect in Lym1 mice.[4] These evidences, together with the other autoimmune disorders observed in our patient and other NFKB2 mutant individuals, suggest an autoimmune basis for secondary hypoadrenalism. Moreover, as pointed out by a previous study,[1] the concurrence of mucocutaneous candidiasis, endocrinopathy, and autoantibodies against endocrine organs resembles the clinical features of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 (MIM 240300), a genetic disorder caused by mutations in the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene. AIRE regulates the expression of tissue-specific self-antigens within the thymus, a process critical in negative selection of T cells.[20] A recent study demonstrated that NF-κB directly regulates AIRE expression through a highly conserved transcription enhancer sequence.[21] Indeed, thymus AIRE expression was significantly reduced, and visceral lymphocytic infiltrations were observed in Nfkb2Lym1/Lym1 and Nfkb2−/− mice.[16,22]

In conclusion, we demonstrate a heterozygous protein-truncating mutation (c.2563 A>T, p.855: Lys>∗) in NFKB2 results in early-onset CVID and ACTH deficiency. The mutation disrupts an evolutionary conserved domain required for p100 proteolyzation and activation. Our study broadens both the clinical and genetic spectrum of NFKB2 mutants, and verifies autoimmunity and NK cell defects in these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the patient and her parents for participation in the study.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone, AIRE = autoimmune regulator, ANA = antinuclear antibodies, ANCA = antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, CVID = common variable immunodeficiency, GAPDH = glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, HBV = hepatitis B virus, IκB = inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, IKKα = IκB kinase α, IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin, Lys = lysine, NEMO = nuclear factor kappa-B essential modulator, NFKB2 = nuclear factor kappa-B subunit 2, NFKBIA = nuclear factor-kappa-B inhibitor alpha, NIK = nuclear factor-kappa-B inducing kinase, NK cells = natural killer cells, PBMC = peripheral blood mononuclear cells, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, Ser = serine.

This work was supported by the National Key Program of Clinical Science (grant number WBYZ2011-873).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- 1.Chen K, Coonrod EM, Kumanovics A, et al. Germline mutations in NFKB2 implicate the noncanonical NF-kappaB pathway in the pathogenesis of common variable immunodeficiency. Am J Hum Genet 2013; 93:812–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee CE, Fulcher DA, Whittle B, et al. Autosomal-dominant B-cell deficiency with alopecia due to a mutation in NFKB2 that results in nonprocessable p100. Blood 2014; 124:2964–2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindsley AW, Qian Y, Valencia CA, et al. Combined immune deficiency in a patient with a novel NFKB2 mutation. J Clin Immunol 2014; 34:910–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brue T, Quentien MH, Khetchoumian K, et al. Mutations in NFKB2 and potential genetic heterogeneity in patients with DAVID syndrome, having variable endocrine and immune deficiencies. BMC Med Genet 2014; 15:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lougaris V, Tabellini G, Vitali M, et al. Defective natural killer-cell cytotoxic activity in NFKB2-mutated CVID-like disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 135:1641–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Hanson S, Gurugama P, et al. Novel NFKB2 mutation in early-onset CVID. J Clin Immunol 2014; 34:686–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilmore TD. Introduction to NF-kappaB: players, pathways, perspectives. Oncogene 2006; 25:6680–6684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paciolla M, Pescatore A, Conte MI, et al. Rare mendelian primary immunodeficiency diseases associated with impaired NF-kappaB signaling. Genes Immun 2015; 16:239–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun SC. Non-canonical NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Cell Res 2011; 21:71–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantakamalakul W, Jaroenpool J, Pattanapanyasat K. A novel enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-K562 flow cytometric method for measuring natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxic activity. J Immunol Methods 2003; 272:189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu L, Wang Z, Chen X, et al. Application of measuring human peripheral NK cell activity with flow cytometry in diagnosis for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2009; 17:1497–1501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao G, Harhaj EW, Sun SC. NF-kappaB-inducing kinase regulates the processing of NF-kappaB2 p100. Mol Cell 2001; 7:401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang C, Zhang M, Sun SC. beta-TrCP binding and processing of NF-kappaB2/p100 involve its phosphorylation at serines 866 and 870. Cell Signal 2006; 18:1309–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amir RE, Haecker H, Karin M, et al. Mechanism of processing of the NF-kappa B2 p100 precursor: identification of the specific polyubiquitin chain-anchoring lysine residue and analysis of the role of NEDD8-modification on the SCF(beta-TrCP) ubiquitin ligase. Oncogene 2004; 23:2540–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. NF-kappaB in immunobiology. Cell Res 2011; 21:223–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tucker E, O’Donnell K, Fuchsberger M, et al. A novel mutation in the Nfkb2 gene generates an NF-kappa B2 “super repressor”. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2007; 179:7514–7522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orange JS, Brodeur SR, Jain A, et al. Deficient natural killer cell cytotoxicity in patients with IKK-gamma/NEMO mutations. J Clin Invest 2002; 109:1501–1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandey R, DeStephan CM, Madge LA, et al. NKp30 ligation induces rapid activation of the canonical NF-kappaB pathway in NK cells. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2007; 179:7385–7396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrioli M, Pecori Giraldi F, Cavagnini F. Isolated corticotrophin deficiency. Pituitary 2006; 9:289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson MS, Su MA. Aire and T cell development. Curr Opin Immunol 2011; 23:198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haljasorg U, Bichele R, Saare M, et al. A highly conserved NF-kappaB-responsive enhancer is critical for thymic expression of Aire in mice. Eur J Immunol 2015; 45:3246–3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu M, Chin RK, Christiansen PA, et al. NF-kappaB2 is required for the establishment of central tolerance through an Aire-dependent pathway. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:2964–2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.