Abstract

Barth syndrome is known as a highly recognizable X-linked disorder typically presenting with the three hallmarks: (left ventricular non-compaction) cardiomyopathy, neutropenia, and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria. Furthermore, growth retardation, mild skeletal myopathy, and specific facial features as well as mitochondrial dysfunction in muscle are frequently seen. Underlying mutations are found in TAZ and lead to defective cardiolipin remodeling.

Here, we report atypical clinical manifestations of TAZ mutations in two male patients initially presenting with growth retardation and very mild skeletal myopathy. As other phenotypic hallmarks were missing, Barth syndrome had not been suspected in these patients. One of them has been incidentally diagnosed in the frame of an in-depth cardiolipin research analysis, while the underlying genetic defect was unexpectedly identified in the second one by exome sequencing.

Conclusion: These cases underline that TAZ mutations might well be an underdiagnosed cause of skeletal myopathy and growth retardation and do not necessarily manifest with the full clinical picture of Barth syndrome.

Keywords: 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria, Barth syndrome, Failure to thrive, Gowers’ sign, Myopathy

Introduction

Barth syndrome (BTHS, MIM #302060, for review Roberts et al. 2012; Clarke et al. 2013) is known as a distinctive clinical syndrome characterized by (cardio)myopathy, neutropenia, and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria (3-MGA-uria). Most prominent and often the key to diagnosis are the cardiac features including left ventricular dilation, hypertrophy, and non-compaction, with varying degrees of congestive heart failure and endocardial fibroelastosis. Sudden cardiac death and ventricular arrhythmia have been reported. Cardiomyopathy can be apparent at birth, or even in utero, but mostly develops within the first year of life (Cardonick et al. 1997; Spencer et al. 2006). Exercise intolerance due to cardiac problems in combination with skeletal myopathy is common. Most patients have delayed milestones and muscular hypotonia but are ambulatory and do not show progression of these symptoms. Prepubertal growth delay is another frequent finding. Neutropenia varies between mild depression of neutrophils and complete absence and can be cyclic. Patients are at risk for overwhelming bacterial infections, especially in the newborn period and chronic aphthous stomatitis due to candida infections. More recently, a cognitive phenotype and typical facial features have been added to the phenotypic description of BTHS. Mutations in X-chromosomal TAZ encoding tafazzin underlie BTHS. Tafazzin is a transacylase located in the mitochondrial membrane and involved in cardiolipin (CL) remodeling. CL is a phospholipid in the mitochondrial membrane and as such holds a key position in mitochondrial energy metabolism and apoptosis. Heterozygous females are asymptomatic.

We describe two atypical patients with mutations in TAZ who initially presented with growth retardation and mild myopathy without any other cardinal features of BTHS such as cardiomyopathy, 3-MGA-uria, or neutropenia.

Patients and Methods

Patient 1

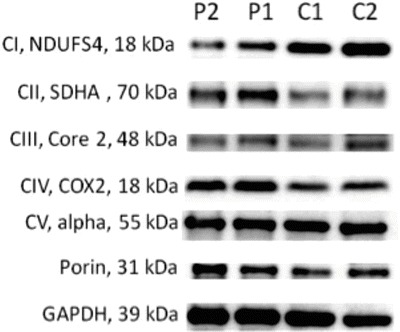

The male patient was born to healthy unrelated German parents after a normal pregnancy at 35 weeks of gestation with a birth weight on p10. Postnatal adaption was uneventful. A slight delay in motor development was already apparent during the first year. At the age of nearly 4 years, he was referred for evaluation of growth retardation (Fig. 1). Physical examination revealed chubby cheeks and a mild myopathy with positive Gowers’ sign. Creatine kinase, leukocyte count, and serum lactate were normal; urinary organic acid analysis (UOAA) was not performed. Over time myopathy became more apparent, as did the short stature. At the age of 5.5 years, serum lactate was elevated (4.9 mmol/l, normally <2 mmol/l); serum cholesterol, leukocyte count, and UOAA were normal. Based on the involvement of two organ systems (growth retardation and myopathy) and the elevated serum lactate, an oxidative phosphorylation system (OXPHOS) disorder was suspected, and a fresh muscle biopsy was performed. It showed strongly reduced mitochondrial energy producing capacity (ATP + CrP production from pyruvate 12.7 nmol/h/mUCS, reference range 42.1–81.2) with deficiencies of the mitochondrial complexes I (74%), III (27%), and IV (22%). Western blot showed a reduced amount of complex I (Fig. 1). Analysis of the OXPHOS in fibroblasts was normal. Fibroblasts were sent as control cells for validation of the method of CL analysis in muscle, without clinical suspicion of this diagnosis (the biochemical, but no genetic or clinical data are described in Houtkooper et al. 2009). CL analysis of muscle tissue showed the typical pattern of TAZ deficiency with a decrease in tetra-linoleoyl species of CL and an accumulation of monolyso-CL. Sanger sequencing of TAZ revealed a hemizygous frameshift mutation in exon 9 of TAZ (c.655_656insAAGT, p.(Asp219Glufs*6); RefSeq NM_000116.4) (Houtkooper et al. 2009). At the age of 7 years, 3-methylglutaconic acid (3-MGA) was found elevated for the first time (after more than five unremarkable UOAA), being 50 μmol/mmol creatinine (normally <20 μmol/mmol creatinine); leukocyte count was normal. Echocardiography was repeatedly normal until the age of 9 years when a diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle was detected. Shortly afterward, the patient developed heart failure with a shortening fraction <20% and highly elevated NT-pro-BNP (2,002 ng/l). The end-diastolic diameter of the left ventricle was still within limits (37 mm, p75) as was the myocard. Cardiac function improved significantly under treatment with ACE inhibitors (NT-pro-BNP 1,136 ng/l).

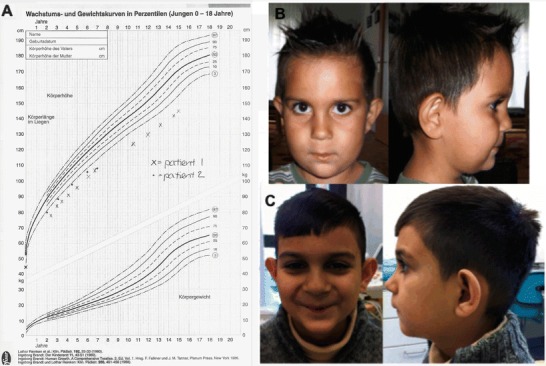

Fig. 1.

Clinical findings in our patients. (a) Growth charts of patient 1 (X) and patient 2 (o). (b) Patient 2 at age six and (c) 10 years; note the chubby cheeks and large ears

Currently, the patient is 12 years old; his height is 129 cm (5 cm < p3). The proximal myopathy is stable; he is fully ambulatory, but has difficulties climbing stairs. He successfully attends regular school, joins sports classes, and never experienced frequent or serious infections. Recently, diuretics had to be added to cardiac treatment due to worsening shortening fraction (18%) and increasing NT-pro-BNP (2,346 ng/l). Still the dimension of the left ventricle is within limits (45 mm, p90), but end-diastolic diameter is increased.

Patient 2

A 6-year-old boy of Roma decent was primarily referred because of growth retardation. Length, weight, and head circumference had been normal at birth and crossed the p3 from age 12 months onward, remaining stable from then (Fig. 1). Upon physical examination, mild generalized muscular hypotonia without functional impairment was present. He had chubby cheeks and large ears (Fig. 1). His motor and intellectual development was age appropriate.

Gastrointestinal, endocrinological, and nutritional workup revealed no diagnostic evidence, and serum lactate, serum amino acids, creatine kinase, and UOAA were normal. MRI/MRS of the brain was unremarkable. At the age of nearly 8 years, triggered by febrile infection, the patient presented with acute episodes of painless muscular weakness and significant exercise intolerance. Clinical examination revealed muscular hypotonia and positive Gowers’ sign in the absence of muscular atrophy. Metabolic tests as described above were repetitively normal as was myosonography.

The combination of unexplained muscular symptoms and persistent growth retardation prompted mitochondrial workup. A muscle biopsy showed reduced activity of complexes I (50%), III (50%), and IV (88%) and the oligomycin-sensitive ATPase (71%) in relation to citrate synthase (related to the lowest level of normal). The ratio of CCCP versus ADP-stimulated respiration of pyruvate + malate was increased to 1.43 (normally 1.00 ± 0.09) and therefore indicative for a deficiency in ATP synthesis, including the F1F0 ATP synthase, the adenine nucleotide translocator, and mitochondrial phosphate carrier. Western blot analysis showed a reduction especially of complex I (Fig. 2). In parallel, exome sequencing (performed essentially as described in Haack et al. 2014) revealed a known pathogenic hemizygous mutation c.281G>A, p.(Arg94His) in TAZ (RefSeq NM_000116). CL analysis in leucocytes was consistent with TAZ deficiency (CL 13 pmol/mg protein, normally >130, in Barth patients <30; monolyso-CL/CL ratio 3.43, normally <0.007, in Barth patients >2.52, performed as described in Bowron et al. 2013). Currently, at age 10 years, the patient shows persistent growth retardation (Fig. 1) and very mild exercise intolerance. The boy is able to participate in normal school activities, can run and play but complains that longer walks or hikes cause muscle fatigue and pain. Cardiac evaluation, leukocyte count, and UOAA were repeatedly normal.

Fig. 2.

Western blot analysis of oxidative phosphorylation enzymes in muscle. Western blot analysis (SDS-PAGE) of oxidative phosphorylation enzymes was performed by blotting 10 μg of protein loaded on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and probing with the respective antibodies as previously reported (Feichtinger et al. 2014). A significant decrease was found in complex I in both patients

Discussion

The two patients presented here did not exhibit the classical hallmarks of BTHS at initial presentation and also did not develop the full clinical phenotype during the course of disease (Table 1). Therefore, it would be more precise to describe them as being TAZ-deficient or to refer to a BTHS spectrum where these patients would be at the mild end.

Table 1.

Clinical signs and symptoms seen in our patients compared with patients reported in literature

| Clinical sign or symptom | Estimated frequency in Barth syndrome | P1 at initial presentation | P1 during the disease course | P2 at initial presentation | P2 during the disease course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiomyopathy (any type) | 70% in first year (n = NA (Clarke et al. 2013)), 91% (n = 16 (Rigaud et al. 2013)), 94% (n = 73, (Roberts et al. 2012)) | − | + | − | − |

| Delayed motor milestones | 61–72% (n = 73 (Roberts et al. 2012)) | + | + | + | + |

| Neutropenia | 69% (n = 73 (Roberts et al. 2012)), 73% (n = 16 (Rigaud et al. 2013)), 90% (n = NA (Clarke et al. 2013)) | − | − | − | − |

| 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria | 50% (n = 16, (Rigaud et al. 2013)), 87% (n = 56 (Wortmann et al. 2013)), 100% (n = 6 (Ferri et al. 2013)) | − | + | − | − |

| Growth delay | 50% (n = 16 (Rigaud et al. 2013)), 58% (n = 34 (Spencer et al. 2006)) | + | + | + | + |

Both males were referred for growth retardation. The additionally discovered muscular signs and symptoms were not perceived as limiting in daily life; however, one of the patients had a positive Gowers’ sign at presentation, and the other developed it during the course. In none of them BTHS was suspected on clinical grounds. One of them has been incidentally diagnosed in the frame of an in-depth cardiolipin research analysis, while the underlying genetic defect was unexpectedly identified in the second one by exome sequencing.

In the first patient, a previously unreported predicted loss-of-function mutation was found, and its pathogenicity was proven by CL analysis (Houtkooper et al. 2009). Interestingly, the mutation found in the second patient, with growth retardation and very mild myopathy at age 10 years, has been described earlier in a severely affected patient presenting with fetal cardiomegaly from 32 weeks of gestation who died on day 12 of life (Brady et al. 2006). Of note, also this patient had never displayed 3-MGA-uria or leukopenia.

Muscle biopsies have been performed in both patients due to suspicion of a defect in mitochondrial energy metabolism. Interestingly, biochemical investigations revealed a clear combined defect of oxidative phosphorylation enzymes in both patients with a predominantly decreased amount of complex I. Investigation of mitochondrial energy metabolism in muscle tissue has only been reported from a very limited number of BTHS patients. The predominant decrease of complex I is in line with previously published data and can be explained by impaired remodeling of CL in these patients, which directly affects the respiratory chain structure and function (Dudek et al. 2013).

The presented cases extend the mutational and phenotypic spectrum of BTHS. More important, they underline that TAZ mutations do not have to manifest with the full phenotypic spectrum of BTHS. Additionally, these cases illustrate that unexplained growth retardation with involvement of a second organ system (e.g., myopathy) should prompt workup for a mitochondrial disorder. To avoid invasive procedures such as a muscle biopsy and given its increasing availability, exome sequencing should be considered an early diagnostic step in this clinical setting. Specific studies of CL metabolism may be valuable concerning the evaluation of unclear variants.

Abbreviations

- BTHS

Barth syndrome

- CL

Cardiolipin

- UOAA

Urinary organic acid analysis

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Charlotte Thiels, Martin Fleger, Martina Huemer, Richard J. Rodenburg, Frederic M. Vaz, Riekelt H. Houtkooper, Tobias B. Haack, Holger Prokisch, René G. Feichtinger, Thomas Lücke, Johannes A. Mayr, and Saskia B. Wortmann declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. Additional informed consent was obtained from all patients for which identifying information is included in this article.

Authors’ Contributions

Saskia Wortmann designed the study, collected the clinical info, and wrote the paper. Charlotte Thiels, Martin Fleger, Martina Huemer, and Thomas Lücke were the attending clinicians and collected the clinical info. Tobias Haack and Holger Prokisch performed the exome sequencing on patient 2. Richard Rodenburg, Frederic Vaz, Riekelt Houtkooper, René G. Feichtinger, and Johannes Mayr performed the biochemical experiments. All authors revised the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

Contributor Information

Saskia B. Wortmann, Email: s.wortmann-hagemann@salk.at

Collaborators: Matthias R. Baumgartner, Marc Patterson, Shamima Rahman, Verena Peters, Eva Morava, and Johannes Zschocke

References

- Bowron A, Frost R, Powers VE, Thomas PE, Heales SJ. Steward CG (2013) Diagnosis of Barth syndrome using a novel LC-MS/MS method for leukocyte cardiolipn analysis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(5):741–746. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9552-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady AN, Shehata BM, Fernhoff PM. X-linked fetal cardiomyopathy caused by a novel mutation in the TAZ gene. Prenat Diagn. 2006;26(5):462–465. doi: 10.1002/pd.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardonick EH, Kuhlman K, Ganz E, Pagotto LT. Prenatal clinical expression of 3-methylglutaconic aciduria: Barth syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 1997;17(10):983–988. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199710)17:10<983::AID-PD174>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SL, Bowron A, Gonzalez IL, Groves SJ, Newbury-Ecob R, Clayton N, Martin RP, Tsai-Goodman B, Garratt V, Ashworth M, Bowen VM, McCurdy KR, Damin MK, Spencer CT, Toth MJ, Kelley RI, Steward CG. Barth syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;12:8–23. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek J, Cheng IF, Balleininger M, Vaz FM, Streckfuss-Bömeke K, Hübscher D, Vukotic M, Wanders RJ, Rehling P, Guan K. Cardiolipin deficiency affects respiratory chain function and organization in an induced pluripotent stem cell model of Barth syndrome. Stem Cell Res. 2013;11(2):806–819. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feichtinger R, Weis S, Mayr JA, Zimmermann F, Gellberger R, Sperl W, Kofler B (2014) Alterations of oxidative phosphorylation complexes in astrocytomas. Glia 62(4):514–525 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ferri L, Donati MA, Funghini S, Malvagia S, Catarzi S, Lugli L, Ragni L, Bertini E, Vaz FM, Cooper DN, Guerrini R, Morrone A. New clinical and molecular insights on Barth syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;14:8–27. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haack TB, Gorza M, Danhauser K, Mayr JA, Haberberger B, Wieland T, Kremer L, Strecker V, Graf E, Memari Y, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of eleven patients and five novel MTFMT mutations identified by exome sequencing and candidate gene screening. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;111:342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtkooper RH, Rodenburg RJ, Thiels C, van Lenthe H, Stet F, Poll-The BT, Stone JE, Steward CG, Wanders RJ, Smeitink J, Kulik W, Vaz FM (2009) Cardiolipin and monolysocardiolipin analysis in fibroblasts, lymphocytes, and tissues using high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry as a diagnostic test for Barth syndrome. Anal Biochem 387(2):230–237. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2009.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rigaud C, Lebre AS, Touraine R, Beaupain B, Ottolenghi C, Chabli A, Ansquer H, Ozsahin H, Di Filippo S, De Lonlay P, Borm B, Rivier F, Vaillant MC, Mathieu-Dramard M, Goldenberg A, Viot G, Charron P, Rio M, Bonnet D, Donadieu J. Natural history of Barth syndrome: a national cohort study of 22 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:8–70. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AE, Nixon C, Steward CG, Gauvreau K, Maisenbacher M, Fletcher M, Geva J, Byrne BJ, Spencer CT. The Barth Syndrome Registry: distinguishing disease characteristics and growth data from a longitudinal study. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(11):2726–2732. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CT, Bryant RM, Day J, Gonzalez IL, Colan SD, Thompson WR, Berthy J, Redfearn SP, Byrne BJ (2006) Cardiac and clinical phenotype in Barth syndrome. Pediatrics 118(2):e337–e346 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wortmann SB, Kluijtmans LA, Rodenburg RJ, Sass JO, Nouws J, van Kaauwen EP, Kleefstra T, Tranebjaerg L, de Vries MC, Isohanni P, Walter K, Alkuraya FS, Smuts I, Reinecke CJ, van der Westhuizen FH, Thorburn D, Smeitink JA, Morava E, Wevers RA. 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria–lessons from 50 genes and 977 patients. Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(6):913–921. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9579-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]