Abstract

Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency, characterized by low plasma levels of the serine protease inhibitor AAT, is associated with emphysema secondary to insufficient protection of the lung from neutrophil proteases. Although AAT augmentation therapy with purified AAT protein is efficacious, it requires weekly to monthly intravenous infusion of AAT purified from pooled human plasma, has the risk of viral contamination and allergic reactions, and is costly. As an alternative, gene therapy offers the advantage of single administration, eliminating the burden of protein infusion, and reduced risks and costs. The focus of this review is to describe the various strategies for AAT gene therapy for the pulmonary manifestations of AAT deficiency and the state of the art in bringing AAT gene therapy to the bedside.

Keywords: alpha-1 antytripsin deficiency, lung disease, gene therapy, adeno-associated vector, adenovirus vectors

Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT), a serum serine protease inhibitor, functions to protect the lung from the activity of the powerful protease neutrophil elastase (NE) (1–7). In addition to its role in regulating NE, AAT inhibits the activity of other neutrophil-released proteases, including proteinase 3, α-defensins, and cathepsin G, and has antiinflammatory and immunomodulatory properties (8–21). Serum deficiency of AAT is associated with an imbalance between proteases and AAT in the lung, leading to slow destruction of the lung parenchyma, a process accelerated by cigarette smoking (1, 3–5, 22–26). The consequence is the development of early-onset panacinar emphysema at ages 35 to 40 years, and a reduced lifespan of approximately 15 to 20 years (3–5, 27–29). The disorder affects 70,000 to 100,000 individuals in the United States (27, 30). AAT deficiency is also associated with childhood and adult liver cirrhosis and, rarely, with hepatocellular carcinoma, panniculitis, and a variety of vasculitic and autoimmune disorders (31–38). Therapies for AAT antitrypsin deficiency have focused primarily on normalizing AAT levels to protect the lung and, to a lesser extent, on strategies to treat the rarer liver diseases (39–51). Because this review is directed toward gene therapy for AAT deficiency lung disease, we focus on the pathogenesis and therapy for the emphysema associated with AAT deficiency.

Pathogenesis of Emphysema Associated with AAT Deficiency

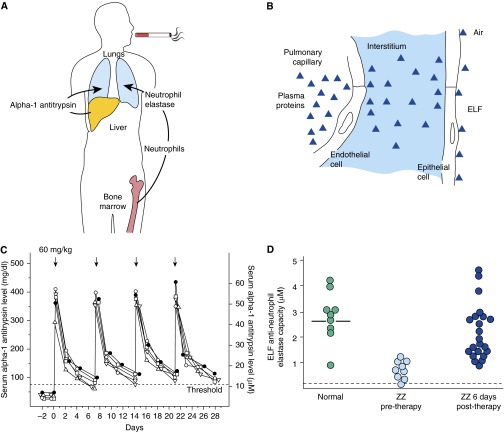

AAT is produced mainly in the liver, reaching the lung by diffusion from the circulation (1, 3–5, 7, 22, 26, 28, 52), with a small percentage secreted locally from mononuclear phagocytes (53, 54), neutrophils (55), bronchial epithelial cells (56, 57), and small intestine epithelial cells (58, 59). The AAT in plasma diffuses into the lung, where it protects the fragile alveolar structures from proteases carried by neutrophils produced in bone marrow. In this context, the pathogenesis of the emphysema associated with AAT deficiency is a tale of three organs: the liver, which produces the AAT; the bone marrow, which generates the neutrophils that carry and release the proteases; and the lung, the organ that is most susceptible to NE–mediated proteolytic destruction (Figure 1A). As will be discussed, the fact that only the lung is destroyed in AAT deficiency is critical in designing an effective gene therapy strategy to prevent the emphysematous destruction of the lung.

Figure 1.

Pathogenesis and current therapy for alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency. (A) Organs involved in the pathogenesis of the pulmonary manifestations of AAT deficiency. (B) Alveolar endothelial-epithelial “barriers” to the diffusion of plasma to the epithelial lining fluid (ELF) of the lower respiratory tract. The endothelial junctions are relatively loose, such that the levels of AAT (52 kD molecular weight) in the interstitium are about 59% of that in plasma. The epithelial junctions are tight, resulting in ELF AAT levels of 5 to 10% that of plasma. (C) Serum levels of AAT after therapy with intravenous AAT purified from pooled human plasma in patients with AAT deficiency. The half-life of AAT is 4.5 days. When 60 mg/kg are administered intravenously, the serum levels of AAT rise dramatically and then fall over 1 week to ∼11 μM, the protective levels. Mass concentrations (left ordinate, mg/dl; right ordinate, μM). The dashed line represents the protective 11-μM threshold level of AAT. (D) Epithelial lining fluid anti–neutrophil elastase levels 6 days after AAT infusion. These were the key clinical data that led to the Food and Drug Administration approval of ΑΑΤ protein augmentation therapy. B and C are reprinted by permission from Reference 39.

Low circulating levels of AAT are the result of mutations in the SERPINA1 gene (MIM 107,400) (60, 61), with more than 120 naturally occurring alleles identified by migration on isoelectric focusing gels and by genotyping (30, 62–64). The different forms have been classified as normal, deficient, dysfunctional, or null variants. The normal allele is the M form (65), present in more than 98% of the population. The most common deficient variants are the severe Z allele, observed with high frequency in whites in Northern European countries and North America, and the milder S form, with high prevalence in the Iberian Peninsula (30, 35, 63). The vast majority of cases of emphysema associated with AAT deficiency are caused by homozygous inheritance of the severe Z variant, with a single amino acid substitution of lysine for glutamic acid at position 342 (E342K) (66). The Z mutation causes the AAT protein to polymerize in hepatocytes, preventing secretion into the blood (28, 30, 35, 66–70). The S allele, a single amino acid substitution of a glutamic acid by a valine at position 264 (E264V), results in an instable protein with reduced serum half-life (71–74). Most AAT genotypes originate from a combination of the M allele and, to a lesser extent, the mutant S and Z variants. Individuals homozygous for the Z mutation (ZZ) have plasma AAT levels 10 to 15% of the levels of those of the normal M allele and account for more than 95% of cases of clinically recognized AAT deficiency (4, 5, 7, 26, 30, 36, 75).

AAT Augmentation Therapy with Human AAT Purified from Pooled Plasma

In the context that AAT deficiency is a plasma deficiency of a liver-produced protein, and that the emphysema develops because there is insufficient AAT to protect the lung, the therapeutic strategy to prevent emphysema was to augment plasma AAT levels above that necessary to protect the lung from proteolytic destruction. The therapeutic strategy for AAT protein augmentation therapy was developed initially by Gadek and colleagues (1, 44). The pivotal study demonstrating efficacy of augmentation therapy that led to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval was performed by Wewers and colleagues (39).

The fragile alveolar structures are at risk of destruction by neutrophil proteases, particularly NE. Neutrophils are produced in the bone marrow and circulate in blood, but a significant proportion marginate in the pulmonary capillaries, putting the lung at risk of the burden of NE (Figure 1A). AAT, the dominant systemic antiserine protease, is produced mostly by hepatocytes. AAT circulates systemically, but its major function is to protect the lung from NE. If the serum levels of AAT are below 11 μM (570 μg/ml), there is insufficient AAT to protect the alveoli from NE, resulting in progressive alveolar destruction and eventually emphysema. The AAT plasma threshold level of 11 μM (570 μg/ml) was determined on the basis of the clinical observation that emphysema rarely develops in individuals with AAT plasma levels above this threshold (44). The 11-μM AAT plasma level has been reviewed by the FDA and other European regulatory agencies and has been maintained as the “protective threshold” for more than 27 years (43, 76, 77). The levels of AAT (molecular weight [MW], 52 kD) in the interstitium are ∼50% of plasma levels (Figure 1B). The cell tight junctions of the alveolar epithelium restrict diffusion of AAT such that the alveolar epithelial lining fluid (ELF) AAT levels on the air side of the epithelium of ∼5 to 10% of plasma levels. Gadek and colleagues (1, 44) hypothesized that if AAT was infused intravenously, and if AAT levels (and consequently anti–NE levels) in alveolar ELF were normalized, then the alveolar interstitium levels of AAT would have to be normalized. This concept formed the basis for the rationale of the “biochemical efficacy” of AAT augmentation therapy. To validate this hypothesis, Gadek and colleagues purified AAT from pooled human plasma and infused it intravenously into five patients with AAT deficiency (44). The study demonstrated that, with weekly infusions of 60 mg/kg of purified AAT, serum and lung ELF levels remained elevated over the protective threshold (44). Finally, in 1987, Wewers and colleagues demonstrated the same concept in larger numbers of patients with AAT deficiency, using human plasma purified AAT from a commercial source (39). The half-life of AAT is 4.5 days. When 60 mg/kg was administered intravenously, the serum levels of AAT rose dramatically and then fell over 1 week to ∼11 μM (570 μg/ml), the protective level. In lung ELF, the anti-NE capacity was normalized (39) (Figures 1C and 1D). This study was the basis of the FDA approval of AAT augmentation therapy. Even though the FDA approval was granted on the basis of the logic of biochemical efficacy, no clinical efficacy was demonstrated at the time. In a recent 2-year multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (the RAPID trial) Chapman and colleagues (78) provided evidence that the therapy slows the progression of lung destruction, measured by computer tomography lung density at total lung capacity as the primary outcome.

Rationale for Gene Therapy for AAT Deficiency

AAT augmentation therapy with the human AAT protein is costly, requires weekly to monthly intravenous infusions of purified AAT from pooled human plasma, and has the risk of allergic reactions and viral contamination (43, 64, 79). In contrast, treating AAT deficiency with gene therapy rather than with the AAT protein theoretically offers the advantage of a single administration, eliminating the burden of the intermittent purified protein infusions, with consequent improved patient compliance. Finally, in contrast to intravenous AAT augmentation therapy, in which there are constantly changing levels from peaks after infusion to troughs just prior to the next infusion, gene therapy produces constant levels of AAT. If effective, gene therapy presents a lower risk, fewer issues with limitations in supply, and reduced overall drug cost.

The general strategy of AAT gene therapy to augment lung levels of AAT focuses on delivering the normal human M-type AAT complementary DNA (cDNA) under control of a constitutive promoter using a gene transfer vector, so the transduced cells secrete the protein to the blood after a single administration (42, 45, 46, 80, 81). There are two major parameters to be considered in designing AAT gene therapy: (1): the vector to deliver the gene and (2) the site/organ to be modified genetically to express the gene. A variety of approaches have been used (Table 1, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Experimental animal gene therapy for ΑΑΤ deficiency

| Vector | Animal Model | Route | Dose | Serum Human AAT Levels* | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrovirus† | Mice | Intraperitoneal | 3 × 106 cells/g | 3.3 ± 1.1 µg/ml | 4 wk after transplant, lung ELF AAT levels 0.96 ± 0.04 µg/ml | (80) |

| Retrovirus‡ | Dogs | Spleen | 109 hepatocytes | 4.5 µg/ml | Transient expression; peak 6-8 d; levels undetectable by Day 47 | (82) |

| Retrovirus§ | Mice | Portal vein | Up to 2 × 107 CFU | 1 µg/ml|| | Expression variable but sustained for 6 mo | (83) |

| Retrovirus§ | Rats | Portal vein | 3 × 106 PFU | 4 µg/ml | 2 µg/ml AAT levels sustained for 120 d | (84) |

| Retrovirus¶ | Mice | Tail vein | 3 × 106 cells | 420 ng/ml | AAT levels decreased after 3 wk, detected up to 20 wk | (85) |

| DNA/liposomes | Mice | Tail vein | 80 ng** | NA | Higher AAT expression in liver with DNA encapsulated in small liposomes vs. large liposomes, at 7 d | (95) |

| DNA/liposomes | Mice | Tail vein | 100 ng** | 150 ng/ml†† | Single vs. repetitive treatment showed no differences in protein levels; partial hepatectomy increased levels 6-fold | (96) |

| DNA/liposomes | Rabbits | Ear injection, aerosol | 500 µg** | NA | Protein expression detected in lung and liver up to 7 d after transfection for both routes; higher mRNA expression in lung via aerosol delivery, but higher in liver by ear injection | (92) |

| DNA/liposomes | Rabbits | Ear injection, aerosol | 500 µg** | NA | Weekly administration. Protein expression detected in lung and liver up to 4 wk. Safety evaluation of repeated administration | (91) |

| DNA | Rats, cats | Intrahepatic | 1 mg in rats, 5 mg in cats | 23.1 ng/ml,‡‡ 35 ng/ml§§ | Transient expression up to 14 d, peak at 2 d | (88) |

| DNA/liposomes | Mice | Tail vein | 100 ng** | 30.0 ± 9.0 ng/ml | Expression in hepatocytes up to 14 d with small liposomes. Transient expression; higher level in plasma 1 d after repeated administration | (97) |

| DNA/liposomes | Mice | Tail vein | Up to 500 ng** | >150 ng/ml|||| | Higher, extended expression (up to 160 d) with liposome encapsulated plasmid, followed by partial hepatectomy | (98) |

| DNA/liposomes | Rats | Tail vein | Up to 2 mg** | ND | Conjugation to mannose-terminal glycoprotein to target macrophages; low AAT levels in ELF 7.4 ± 3.4pM. AAT mRNA detected in 1% pulmonary alveolar macrophages | (94) |

| DNA, transfected myoblasts | Mice | Intramuscular | Up to 50 µg DNA, 5 × 105 cells | >20 ng/ml | Peak at 1 wk and low levels 2 wk after DNA transfection; ex vivo, transplanted myoblasts, steady expression in serum up to 10 wk | (86) |

| DNA | Mice | Tail vein¶¶ | Up to 50 µg | 500 µg/ml*** | AAT levels dropped 100-fold from Day 1 to Day 30 and persisted at a low level for up to 6 mo; repeated administration resulted in sustained high levels | (87) |

| Linear DNA | Mice | Tail vein¶¶ | 40 µg | >100 µg/ml*** | AAT levels remained high up to 9 mo | (90) |

| DNA/liposomes | Mice | Tail vein | Up to 500 ng** | >200 µg/ml | Hepatocyte targeting liposome/DNA complex with asialofetuin ligand (ASF); ASF coupling yielded higher protein levels in serum, sustained for up to 12 mo after partial hepatectomy | (93) |

| DNA | Mice | Tail vein¶¶ | Up to 320 µg | 6 mg/ml | Therapeutic, stable AAT plasma levels up to 4 mo; AAT promoter higher levels than CMV promoter; DNA dose response expression of AAT in plasma | (89) |

| Ad5 | Cotton rats | Intratracheal | Up to 3 × 109 PFU | NA | First in vivo gene therapy. AAT present in ELF at early time point, up to 7 d; maximal expression at Day 3 (400 ng/ml) | (42) |

| Ad5 | Rats | Intraportal | 1010 PFU | 1 µg/ml | In vivo transfer to hepatocytes; levels detectable up to Day 28. | (101) |

| Ad5 | Human umbilical veins | Ex vivo | 1010 PFU | 13 µg/ml | AAT detected at 13 µg/ml in umbilical cord perfusate 24 h after transduction | (104) |

| Ad5 | Sheep | Intracarotid; intrajugular | Up to 4 × 1010 PFU | ND | Endothelial cells in jugular veins and carotid arteries expressed AAT mRNA up to 14 d; no AAT detectable in serum | (105) |

| Ad5 | Cotton rats | Intraperitoneal | Up to 1011 PFU | 3.4 µg/ml | Serum AAT levels peaked at 4 d after mesothelium transfer and declined over time | (103) |

| Ad5 | Mice | Portal vein, vena cava | 1010 PFU | 700 µg/ml | Higher levels of expression when using RSV promoter; long-term expression, up to 150 d with level decline over time | (102) |

| Helper-dependent Ad5 | Mice | Tail vein | 2 × 1010 particles | 50 µg/ml | Long sustained expression for >10 mo | (106) |

| Helper-dependent Ad5 | Mice | Tail vein | Up to 3.2 × 1011 particles | 6 mg/ml | Sustained high expression for up to 8 wk | (108) |

| Helper-dependent Ad5, Ad2 | Baboons | Intravenous | Up to 1.4 × 1012 particles/kg | 4 µg/ml | Maximal levels at 3-4 wk sustained; slow decline over a year; serotype 2 circumvents antibodies against Ad5 | (107) |

| AAV2 | Mice | Intramuscular | Up to 1.4 × 1013 particles | 800 µg/ml†††; 400 µg/ml‡‡‡ | AAT levels mouse strain dependent; highest expression levels with CMV promoter, up to 15 wk | (121) |

| AAV2 | Mice | Portal vein | 1 × 1011 vg | 50 µg/ml | 5% of hepatocytes transduction; highest expression with albumin and MMLV LTR promoters | (119) |

| AAV2 | Mice | Portal vein | Up to 3 × 1010 IU | 1 mg/ml | Highest expression level with CB promoter sustained for up to 52 wk | (81) |

| AAV5, AAV2 | Mice | Intrapleural, intramuscular |

Up to 1 × 1011 gc | 1 mg/ml§§§ | AAV5 expression 5-fold higher than AAV2 by both routes; AAV5 levels by intrapleural route were 10-fold higher than IM at the same dose; levels of 900 µg/ml sustained for 40 wk||||||; ELF AAT levels comparable to serum levels | (45) |

| AAV8, AAV5, AAV2, AAV1 | Mice | Portal vein | Up to 1.65 × 1011 particles | 30 mg/ml¶¶¶ | AAV8 best performer at the same dose, 15-fold protein level increase for each 10-fold higher dose of virus; levels sustained for 24 wk for all doses | (120) |

| AAV2 | Mice | Intratracheal | Up to 7 × 1010 drp | 1.5 mg/ml**** | Highest expression levels for up to 12 wk using a CB promoter with a woodchuck promoter response element | (130) |

| AAVrh.10 | Mice | Intrapleural | Up to 1 × 1011 gc | 2.4 mg/ml†††† | Comparison of 25 AAV serotypes; AAVrh.10 maximal expression after intrapleural delivery; high levels sustained for up to 24 wk; functions despite anti-AAV2 and AAV5 preexisting immunity | (46) |

| AAV9, AAV5 | Mice | IN, intratracheal | 1 × 1011 gc | 7.8 ± 7.4 µg/ml‡‡‡‡ | Expression sustained for 217 d; AAV9 higher serum levels than AAV5; IT delivery 3-fold increase compare to IN for AAV9; AAV5 highest concentration in ELF (2,215 ± 1,345 ng/ml) at Day 28, declining 7-fold by Day 196; AAV9 expression stable (189 ± 156 ng/ml); AAV9 vector could be readministered | (133) |

| AAV1, AAV2, AAV3, AAV4, AAV5 | Mice | Intramuscular | 1 × 1011 vg | 1 mg/ml§§§§ | Sustained protein expression for up to 84 wk; AAV1 highest muscle transduction efficiency and highest serum expression levels | (123) |

| AAV1 | Mice, rabbits | Intramuscular | Up to 2 × 1013 vg | 1 mg/ml | Preclinical safety study. Dose-dependent expression. Up to 90 d persistent expression in mice; transient expression in rabbits | (117) |

| AAV5 | Mice | Oral||||||||, intratracheal | 2 × 1012 particles | ∼20 µg/ml¶¶¶¶ | No significant differences in AAT levels in serum and lung homogenates (∼50 µg/ml) for either route | (134) |

| AAV2, AAV5, AAV8, AAV9, AAV2 mutants | Mice | Intratracheal, IN | 1 × 1010 vg | ∼30 µg/ml***** | AAV8 highest serum AAT level expression and lung transduction by IT route; IN delivery reached about one-half to one-third of the IT route; levels sustained for all vectors for up to 4 mo | (131) |

| 19 different AAV vectors | Mice | Intratracheal | 1 × 1011 gc | >2.5 µg/ml†††††; >6 µg/ml‡‡‡‡‡ | AAV6 and mutant AAV6.2 (F129L) best in airway epithelium transduction compared with AAV serotypes 1–9, plus novel isolates and engineered vectors§§§§§ | (135) |

| AAV6 | Mice, dogs | IN|||||||||| intrabronchial¶¶¶¶¶ | Up to 2 × 1011 vg in mice | ∼500 µg/ml|||||||||| | AAT levels higher in ELF than in plasma; serum levels sustained in immunodeficient mice for up to 1 yr; serum levels sustained in dogs for up to 120 d; therapeutic levels in lung (300µg/ml) for up to 120 d followed by subtherapeutic levels through Day 200 | (132) |

| Up to 3 × 1013 vg in dogs | 2.5 µg/ml****** | |||||

| AAV1 | Mice | Intramuscular | Up to 8 × 1013 vg/kg | 39.88 ± 8.95 µM†††††† | Preclinical evaluation AAV1 vector for phase II clinical trial | (125) |

| AAVrh.10 | Mice, NHP | Intrapleural | Up to 1 × 1011 gc in mice | NA | Preclinical evaluation for phaseI/II clinical trial; high AAT mRNA expression in chest cavity organs up to 182 d after vector administration in mice and up to 360 d in NHP | (149) |

| Up to 1 × 1013 gc in NHP |

Definition of abbreviations: AAT = alpha-1 antitrypsin; AAV = adeno-associated virus; CB = CMV/chicken β-actin hybrid promoter; CFU = colony forming units; CMV = cytomegalovirus; drp = DNAse resistant particles; ELF = epithelial lining fluid; gc = genome copies; IN = intranasal; IT = intratracheal; IU = infectious units; MMLV LTR = Long terminal repeat from Moloney murine leukemia virus; NA = not assayed; ND = not detected; NHP = nonhuman primate; PFU = plaque-forming units; RSV = respiratory syncytial virus; vg = viral genomes.

Maximal human AAT levels in serum.

Ex vivo murine NIH/3T3 fibroblasts transduction.

Ex vivo autologous hepatocytes transduction.

In vivo after partial hepatectomy.

In animals that expressed the human AAT from albumin promoter-enhancer.

Ex vivo pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells transduction.

Amount of DNA in the DNA/liposome complex.

After partial hepatectomy.

In rats.

In cats.

At 90 d after DNA administration and partial hepatectomy.

Hydrodynamics-based procedure: high-volume tail vein injection.

At Day 1 after transfection.

In severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice.

In C57Bl/6 mice.

At 8 wk, for AAV5 by intrapleural route (1011-gc dose).

For AAV5, intrapleural route, 1011-gc dose.

At 24 wk.

At 6 wk.

At 28 d after administration of 1011 gc, male mice.

For AAV9 at 28 d after intratracheal instillation.

For AAV1.

Oral instillation.

At 6 wk after administration.

At 8 wk, AAV8 by IT route.

For AAV6, 28 d after administration.

For mutant AAV6.2 (F129L) at 28 d after administration.

AAV1, 6, 9, rh.8, rh.10, rh.20, rh.46, rh.64R1, hu.48R3, cy.5R4, 7, 8, rh.2R, rh.32.33, rh.64R2, hu.13, hu.32, hu.37, pi.2, 2, 5, rh.39, rh.43, hu.11, hu.29R, and hu.51.

In mice.

In dogs, using a microsprayer inserted through fiberoptic bronchoscope.

In dogs.

In males at 60 d after vector administration.

Figure 2.

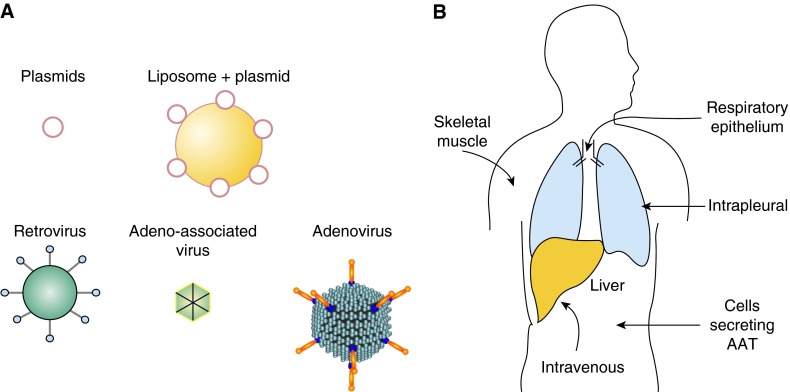

Strategies for gene therapy for treatment of the emphysema associated with alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency. (A) Nonviral and viral vector strategies have been used to deliver the AAT complementary DNA (cDNA) in vivo. Nonviral vectors include naked plasmids or in complex with liposomes. Retroviruses have been used to modify cells ex vivo to secrete AAT, and the cells were then transplanted. Viral vectors for in vivo gene therapy include retrovirus, adenovirus, and adeno-associated virus. (B) Routes used to deliver the AAT cDNA. Cells genetically modified to secrete AAT have been administered to the peritoneum or intravenously (intraportal). Vectors have been administered by various routes including intravenous or intraportal (both primarily target liver), respiratory epithelium, skeletal muscle, or intrapleural, targeting lung and liver (see Tables 1 and 2).

The first gene therapy effort toward treating AAT deficiency was an ex vivo strategy using peritoneal implantation of retrovirus-mediated genetically modified fibroblasts in a mouse model (80). The first in vivo strategy was adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to the respiratory epithelium, demonstrating high levels of human AAT expression in experimental animals (42). This was followed by in vivo strategies to deliver the AAT cDNA, with naked plasmids, plasmids complexed with liposomes, retrovirus, and adenovirus. The current approaches focus primarily on adeno-associated virus (AAV)–based gene therapy, mediating sustained expression of AAT therapeutic levels. Different serotypes and strategies have been explored, and three AAV vectors have moved to clinical studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Human gene therapy for ΑΑΤ deficiency

| Vector | Phase | Doses | Route | Number of Subjects | Maximal Serum AAT Levels Achieved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid-liposome | I | 1,800 µg of liposomes* plus | IN | 5 | 9.0 ± 1.7 µg/mg protein† | (99) |

| 600 µg of plasmid DNA | ||||||

| AAV2 | I | 2.1 × 1012 vg | IM | 12 (3 per dose) | 82 nM‡ | (122) |

| 6.9 × 1012 vg | ||||||

| 2.1 × 1013 vg | ||||||

| 6.9 × 1013 vg | ||||||

| AAV1 | I | 6.9 × 1012 vg | IM | 9 (3 per dose) | 43 nM§ | (124) |

| 2.2 × 1013 vg | ||||||

| 6.0 × 1013 vg | ||||||

| AAV1 | II | 6.0 × 1011 vg/kg | IM | 9 (3 per dose) | 694 nM|| | (47) |

| 1.9 × 1012 vg/kg | ||||||

| 6.0 × 1012 vg/kg | ||||||

| AAVrh.10¶ | I/II | 8.0 × 1012 gc | IP | 10 (5 per dose) | (150) | |

| 8.0 × 1013 gc | IV | 10 (5 per dose) |

Definition of abbreviations: AAT = alpha-1 antitrypsin; AAV = adeno-associated virus; gc = genome copies; IM = intramuscular; IN = intranasal instillation; IP = intrapleural; IV = intravenous; vg = vector genome particles.

1:1 formulation of the cationic lipid N-[1-(2,3,-dioleoyloxy)-p ropyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium chloride (DOTMA) and the neutral lipid dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE).

In nasal lavage fluid.

In one subject from dose group 2.1 × 1013 vg; transient elevation on Day 30 after vector administration.

In two subjects from dose group 6.0 × 1013 vg; remained above 40 nM for 1 year after vector administration.

In the highest-dose cohort; mean 572 nM. Persisted for 1 year after vector administration; dose response levels in all groups.

Food and Drug Administration approved. To be initiated.

In the normal human, AAT is produced mainly by hepatocytes. However, gene therapy strategies have demonstrated that AAT can be produced by many different cells/organs once the gene has been transferred effectively (Table 1, Figure 2). The routes of administration that have been used for in vivo gene therapy for AAT deficiency include intravenous or intraportal vein (targeting liver hepatocytes), direct administration to skeletal muscle, intrabronchial (targeting the respiratory epithelium), and intrapleural (targeting the pleural mesothelium and the liver).

Taken together, these studies demonstrated that augmentation of serum AAT levels can be achieved from various production sites. However, the challenge for systemic delivery of the gene therapy vector remains to achieve the threshold levels of AAT to protect the lung from neutrophil proteases. The target for successful protection of the alveolar structures from neutrophil proteolytic activity are serum AAT levels of 11 μM, 1.2 μM in alveolar ELF, and 5 to 7 μM in the alveolar interstitial tissue (1, 5, 26, 44). To achieve this “biochemical efficacy,” both the serum and the ELF protective levels of AAT must be demonstrated.

Retrovirus Vectors

The earliest experimental model of gene therapy for AAT deficiency used retrovirus vectors (Table 1). The first approach was retrovirus expression of AAT-modified fibroblasts transplanted into the recipient. Garver and colleagues (80) transplanted into the peritoneal cavity of nude mice modified murine NIH/3T3 fibroblasts transduced with a retroviral vector expressing the human AAT cDNA. The AAT produced by the transplanted fibroblasts diffused from the peritoneum to blood and across the lung parenchyma to the lung epithelial surface. Four weeks after transplant, human AAT was detected in serum and lung ELF. The mean concentration of human AAT in the epithelial fluid of the lung was 0.96 ± 0.04 μg/ml, and 3.3 ± 1.1 μg/ml for serum. Although these levels were far below therapeutic levels, these results established the basic concept of gene therapy for AAT deficiency.

Similar results were observed in a dog model after autologous transplant of retroviral transduced hepatocytes (82). Primary hepatocytes were isolated from the animals, transduced with a retroviral vector containing the human AAT cDNA, and transplanted into dogs by administration through the spleen. Human AAT was detected transiently in serum for up to 1 month, reaching the maximal level of 4.6 μg/ml around 1 week after transplant. Other retroviral gene therapy approaches involved in vivo vector transduction of hepatocytes by portal vein infusion in mice (83) and rats (84). Direct hepatic transfer of the retroviral vector after partial hepatectomy produced low, constitutive expression of the human protein in serum for at least 6 months for both models. AAT levels varied among animals, reaching levels of up to 1 μg/ml in mice (83) and 4 μg/ml in rats (84). Saylors and Wall (85) used a retrovirus vector to express the AAT protein in murine hematopoietic cells in vivo. Mice transplanted with bone marrow transduced with a retroviral vector expressing AAT expressed the human protein in serum for up to 20 weeks, with maximal levels of 420 ng/ml, which decreased after Week 3 of administration.

Although early attempts using ex vivo and in vivo retroviral vector delivery failed to reach sustained therapeutic levels of AAT serum, the studies showed that tissues other than those naturally producing AAT could be targeted to produce AAT.

Plasmid Vectors

Nonviral gene transfer has been explored for therapeutic delivery of the human AAT cDNA, using plasmid or linear DNA, or plasmids complexed with lipids that fuse to the cell membrane and improve the efficiency of the delivery of the genetic material to the cell (Table 1). Early studies with naked DNA delivery targeting the liver by intravenous administration showed low, transient AAT expression in serum that dropped to undetectable levels soon after systemic administration in mouse (86, 87), rat (88), and cat models (88). Bou-Gharios and colleagues (86) showed longer AAT expression in serum, up to 10 weeks, with ex vivo transfected myoblasts compared with intramuscular DNA delivery. Zhang and colleagues (87) and Aliño and colleagues (89) demonstrated that sustained levels could be maintained in serum by repeated administration using intravenous hydrodynamics-based transfection. On the basis of the long persistence of AAV genomes in transduced cells, Chen and colleagues (90) explored the hydrodynamics-based method to transfect hepatocytes with linear DNA. Studies in mice showed improved expression in serum compared with circular DNA administration, with sustained AAT levels for up to 9 months (90).

Delivery of DNA in complex with liposomes has also been explored in vivo for AAT gene transfer. Different charge/compositions of lipids in the liposomes have been used, with cationic liposomes the most frequent (91–97). AAT serum expression levels could be increased and sustained longer with partial hepatectomy after the DNA/liposome delivery (93, 96, 98). Comparing different lipid compositions, Crespo and colleagues (98) demonstrated extended serum expression of up to 160 days with liposome-encapsulated plasmid in combination with partial hepatectomy.

Aliño and colleagues (95–97) showed improved hepatocyte transduction in vivo when using small liposomes compared with large liposomes, with longer expression after repeated administration or when followed by partial hepatectomy. Ferkol and colleagues (94) transfected alveolar macrophages in vivo by intravenous administration of DNA/liposome complexes with mannose-terminal glycoprotein conjugates, targeting the alveolar macrophage mannose receptors. This strategy resulted in a low (1%) transfection of the alveolar macrophages and consequent low human AAT expression in ELF (7.4 ± 3.4 pM). Dasí and colleagues (93) targeted liposomes for in vivo specific receptor-mediated uptake in liver using the asialofetuin ligand, which binds to the asialoglycoprotein receptor on hepatocytes. The administration of the targeted liposomes resulted in sustained human AAT protein expression in mouse serum for up to 12 months. Canonico and colleagues (91, 92) used cationic liposomes complexed to plasmids for targeting the respiratory epithelium by aerosol delivery to rabbits. Human AAT was detected in secretory epithelial cells of the airway and along the alveolar epithelium up to 7 days after a single administration (92) and 4 weeks with repeated administration (91).

These preclinical studies were the basis for the first clinical trial for AAT deficiency (99). Five subjects received cationic liposomes complexed with the AAT cDNA plasmid by instillation in the nostril, with the other nostril serving as control. AAT protein levels in nasal lavage fluid increased in the transfected nostril, but not in the control nostril, peaking at 5 days after instillation to one-third of the normal level. Interestingly, local IL-8 levels decreased, suggesting that AAT gene therapy has antiinflammatory activity (Table 2). AAT levels in the nasal lavage were transient, returning to baseline by Day 14 (99).

Adenovirus Vectors

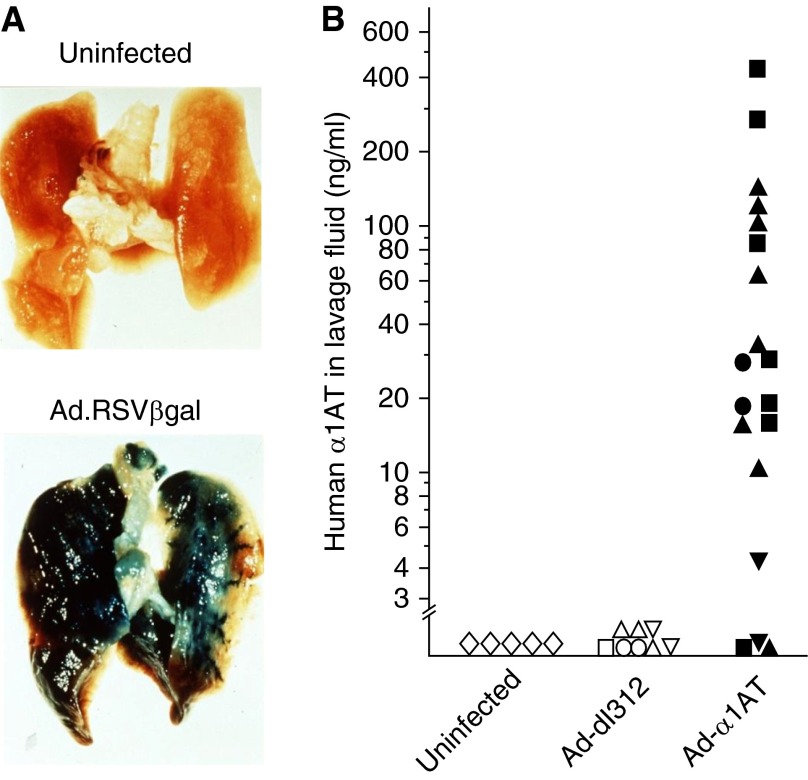

In contrast to plasmids or retrovirus gene transfer, adenovirus gene transfer vectors demonstrated robust transgene delivery and expression in vivo (Table 1). The first successful in vivo adenovirus AAT gene transfer was demonstrated by Rosenfeld and colleagues (42), using an adenovirus vector expressing the human AAT cDNA delivered to the respiratory epithelium of cotton rats by intratracheal instillation. Adenovirus efficiently transduced the lungs as shown by delivery of an Ad vector expressing the β-galactosidase marker (Figure 3A) (100). After Ad-mediated transfer of the human AAT cDNA to the respiratory tract epithelium, human AAT messenger RNA was detected in the respiratory epithelium at early time points, and human AAT protein was found in epithelial cells and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for at least 1 week after vector transfer (42). Human AAT ELF levels were elevated markedly (Figure 3B), but the gene expression was transient secondary to immunity against the Ad vector.

Figure 3.

Adenovirus-mediated gene therapy for alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency. (A) The first demonstration of effective in vivo gene transfer to the lung. An adenovirus gene transfer vector coding for β-galactosidase under the control of an respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) promoter (Ad.RSVβgal) was instilled into the trachea of cotton rats. One week later, the lungs were stained for β-galactosidase (blue) (100). (B) Human AAT in the respiratory epithelial lining fluid (ELF) of cotton rats after intratracheal administration with Ad-AAT. Animals were infected intratracheally with Ad-AAT, an adenovirus vector coding for human AAT; control animals included uninfected animals and those infected with a similar titer of a control adenovirus vector (Ad-dl312). From 1 to 7 days after infection, ELF was obtained by lavage of the lungs. The levels of human AAT were quantified with a human AAT-specific ELISA. Each symbol represents the mean value of an individual animal. Shown are data for animals 1 (open circle, closed circle), 2 (open triangle, 3 closed squares), 3 (open square, closed square), and 7 (open inverted triangle, 3 closed squares) days after vector administration, respectively. No AAT was detected by ELISA in the viral preparations. B is reprinted by permission from Reference 42.

The focus of investigators of adenovirus-mediated AAT gene transfer then shifted to other organs for protein expression, such as the liver (101, 102) and the peritoneal mesothelium (103). Jaffe and colleagues (101) targeted rat hepatocytes for AAT production by intraportal delivery of the Ad vector, and Setoguchi and colleagues (103) transduced mesothelial cells after intraperitoneal administration to cotton rats. Lemarchand and colleagues (104, 105) transferred an adenovirus vector coding for the AAT cDNA to the lumen of intact human umbilical veins ex vivo, resulting in AAT therapeutic levels in vein perfusates (104), and in vivo to jugular veins and carotid arteries in a sheep model (105). Transient expression up to 14 days was detected in the transduced arteries and veins, although AAT was not detected in serum (105). Kay and colleagues (102) used adenovirus vectors coding for AAT to transduce mouse hepatocytes in vivo, which expressed therapeutic levels of serum AAT of up to 700 μg/ml. Schiedner and colleagues (106) and Morral and colleagues (107, 108) used helper-dependent adenoviruses (so-called “gutless” adenovirus vectors) lacking the Ad genome as a strategy to circumvent the immunogenicity and toxicity of Ad vector. Intravenous delivery of these vectors resulted in long-term expression of AAT in serum, up to 10 months in mice (108) and up to 1 year in baboons (107). Together, these studies showed that the adenovirus vectors could drive expression of therapeutic levels of AAT. However, immunogenicity against the adenovirus and resulting inflammatory, antibody, and T-cell responses limit transgene expression duration and readministration of the gene transfer vector, and thus, adenovirus-based strategies for the treatment of AAT deficiency have been abandoned.

AAV Vectors

AAV vectors present several advantages for gene delivery in which the goal is persistent expression (3–5, 40, 41, 45, 46). Compared with Ad vectors, AAV vectors have low toxicity, generating stable, long-term transgene expression as long as the target cells are not proliferating. AAV vectors can transduce a broad range of tissues, and the efficiency of transduction for the different serotypes is likely related to the use of different receptors in the cell. Like any viral vector, transduction efficiency is diminished by the presence of neutralizing antibodies caused by prior infection (109, 110). The use of serotypes with low prevalence in the general population or non–human-derived serotypes circumvents this issue (111, 112). Cell-mediated responses to AAV vectors have been documented for some AAV serotypes (113–116), but little toxicity has been reported, except inflammation when very high doses of vector were given via the hepatic artery or by intramuscular administration (113, 114, 117, 118).

The earliest studies with AAV focused on the use of the AAV2 serotype, but with the discovery of novel serotypes, preclinical studies have focused in finding the best vector for the target organ/tissue (Table 1). Different AAV isolates, AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, AAV6, AAV8, AAV9, and AAVrh.10, as well as engineered new serotypes, have been used for the preclinical development of AAT therapy. From these, AAV1, AAV2, and AAVrh.10, have moved to clinical studies (Table 2).

To achieve the AAT protective levels in the lung, four main strategies have been developed (Table 1, Figures 2, 4, and 5): (1) to the liver by intravenous or intraportal vein, (2) directly to the skeletal muscle (3) to the respiratory epithelium by intranasal or intratracheal delivery, and (4) to the pleural mesothelium and liver by intrapleural delivery.

Figure 4.

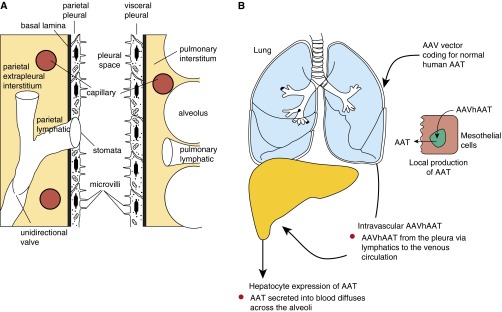

Concept of intrapleural administration of an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector coding for alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT). (A) Anatomy of the human pleura. The pleura membrane encloses the chest cavity attaching to the chest well (parietal pleura) and to the lung parenchyma (visceral pleura). The parietal and visceral pleura contain a single layer of mesothelial cells surrounded by a thin layer of connective tissue. The mesothelium is continuous on the visceral side, with pulmonary lymphatics under the pleura surface. The parietal pleura is interrupted by lymphatic stomata. Both pleura layers are separated by a pleural fluid (0.5–1 ml in humans) that contains proteins that diffuse from blood and are secreted locally. (B) Intrapleural delivery combines local lung delivery via vector transduction of the mesothelial cells lining the pleura, and systemic delivery via vector leaking to the systemic venous system and then primarily to liver hepatocytes. Transduced mesothelial cells will secrete AAT to the lung parenchyma, providing high local levels of AAT. Transduced hepatocytes secrete AAT into the circulation, from which AAT diffuses into the lung, augmenting the locally produced AAT levels.

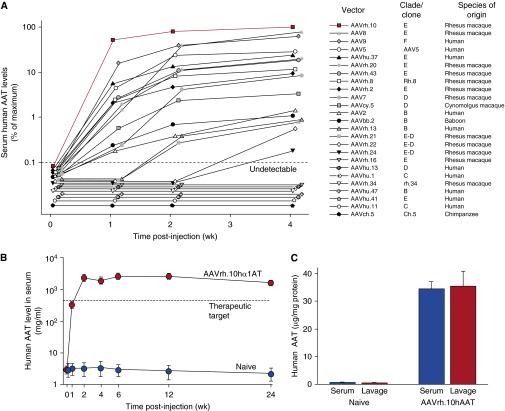

Figure 5.

Assessment of intrapleural administration of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector coding for human alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT). (A) Comparison of 25 different AAV serotypes for AAT expression efficiency after intrapleural administration. The AAV vectors, pseudotyped as indicated and containing the AAT expression cassette and the AAV2 inverted terminal repeats, were administered intrapleurally (5 × 1010 gc) to male C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 per group). Serum ΑAT levels were measured by ELISA up to 4 weeks after administration. The data shown are percentages of the means of five mice, with the levels at Week 4 of AAVrh.10 (in red) used as the 100% point. The human-derived vectors are AAV2, AAV5, AAV9, AAVhu.1, AAVhu.11, AAVhu20, AAVhu.37, AAVhu.41, and AAVhu.47; all others are derived from nonhuman primates. The dashed line represents the assay limit of detection. (B) Persistent AAT levels in serum after AAVrh.10AAT intrapleural administration. AAVrh.10hAAT (1011 gc) was administered intrapleurally to male C57BL/6 mice (n = 4 per group), and serum human AAT levels were assayed by ELISA up to 24 weeks after administration. Values shown are means ± SE. (C) Human AAT levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid compared with serum at 8 weeks after intrapleural administration of 1011 gc AAVrh.10hAAT (C57BL/6 mice; n = 4). Human AAT levels are referenced to total protein. Values shown are means ± SE. gc = genome copies. Reprinted by permission from reference 46.

Target: Liver

Initial therapies with AAV2 targeted the systemic circulation by transduction of hepatocytes by portal vein delivery. Xiao and colleagues (119) demonstrated that 5% of hepatocytes transduction could be achieved in mice by systemic administration, resulting in AAT secretion into the serum. Expression levels were promoter dependent (119). Song and colleagues (81) further showed that higher AAT serum levels, sustained for up to 52 weeks, could be achieved in a mouse model using a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-chicken β-actin hybrid promoter. One of the potential problems with AAV2 is that it naturally infects humans, and the presence of circulating antibodies in humans may reduce AAV2 transduction efficiency (109, 110). With the discovery of new serotypes, vectors were tested for their capacity to transduce hepatic cells after systemic delivery. In a side-by-side comparison with AAV1, 2, and 5, AAV8 reached the highest level of transduction in the liver in a mouse model, and the highest serum AAT levels were sustained for 24 weeks (120).

Target: Muscle

An alternative route for AAV delivery is transduction of skeletal muscle, with the concept of easier administration of the therapeutic to the patients. Song and colleagues (121) demonstrated in two mouse models that systemic delivery of AAT could be achieved by intramuscular delivery of the AAV vector. Expression levels were higher (400 μg/ml) and were sustained for up to 15 weeks in an immunodeficient mouse strain, using a CMV promoter (121). Preclinical studies supported the development of a phase I trial (NCT00377416) for the intramuscular delivery of the AAV2 vector expressing the AAT cDNA driven by a hybrid-chicken β-actin promoter with a CMV enhancer (122). A total of 12 subjects enrolled into four dose cohorts with a range of 2.1 × 1012 to 6.9 × 1013 vector genomes (vg) (Table 2). A low, transient elevation of AAT protein in serum was detected in one subject from the dose group 2.1 × 1013 vg on Day 30 after vector administration (122).

A second clinical trial was initiated for intramuscular delivery using the AAV1 vector (NCT00430768). The decision to use AAV1 was made on the basis of the results of preclinical studies. In a comparison of serotypes AAV1 to AAV5, the AAV1 vector mediated the highest muscle transduction efficiency, with sustained protein expression in serum for up to 84 weeks, and serum AAT levels of 1 mg/ml in mice (123). Compared with AAV2, the AAV1 vector resulted in 200-fold higher serum AAT levels. Preclinical toxicology studies for the AAV1 vector were performed in 170 C57BL/6 mice and 26 New Zealand White rabbits. Murine and rabbit vector studies demonstrated a dose-dependent rise in AAT levels, sustained in the mouse model (117). In the AAV1 phase I clinical trial (Table 2), nine subjects were enrolled, receiving doses of up to 6.0 × 1013 vg. The vector was safe, with sustained levels for up to 1 year for the subjects receiving the highest dose. However, only subtherapeutic levels of AAT (200-fold lower than the threshold) were detected in the two highest-dose cohorts (124). A phase II clinical study (NCT01054339) with a higher dose was initiated, after a new safety study (125). For the phase II clinical study, nine subjects were enrolled with increased dosing of up to 6.0 × 1012 vg/kg. Interim clinical trial results (47) demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in AAT serum levels that peaked 30 days after vector administration, with a serum AAT mean value of 572 nM in the highest-dose cohort. Serum levels had declined to 240 nM by Day 90.

Target: Lung

In the context that the intravenous and intramuscular route for systemic delivery failed to generate therapeutic levels of AAT high enough to protect the lung, the obvious strategy for treating AAT deficiency with AAV vectors is to deliver the vector directly to the lung. Two strategies have been explored: AAV delivery to the respiratory epithelium and AAV delivery to the pleura.

Attempts by gene therapy to target the lung via delivery of AAV vector to the airway epithelium have been frustrated by the antipathogen immune defenses of the lung and other barriers, including the respiratory epithelial fluid and the deficiency of viral receptors on the respiratory epithelial apical surface (126–129). Despite this, several models for airway AAV vector delivery have been evaluated in preclinical studies (Table 1). Early attempts involved the delivery of AAV2 to the respiratory tract of mice by intratracheal administration; transduction efficiency was limited, and high titers of virus were required to achieve effective transgene expression (130). With the discovery of new AAV serotypes, AAV vectors were screened in different preclinical models for their capacity to transduce the airway tract. On the basis of those studies, AAV9, AAV8, and AAV6 seem to be the best vectors for lung transduction via the epithelial route (130–135). In a comparison of AAV9 with AAV2 and AAV5, AAV9 transduced lung cells with high efficiency by intranasal and intratracheal administration, with sustained levels for 217 days in serum and in ELF (189 ± 156 ng/ml) (133). For AAV6, Limberis and colleagues (135) showed that in a side-by-side comparison of 19 different AAV vectors delivered intratracheally in mice, the serotypes 1, 6, 9, rh.8, rh.10, rh.20, rh.46, rh.64R1, hu.48R3, and cy.5R4 were the highest expressers, with AAV6 and a capsid mutant AAV6.2 (F129L) the most successful in airway epithelium transduction. Halbert and colleagues (132) demonstrated a high efficiency of AAV6 in airway transduction in mice by intranasal instillation and in dogs by intrabronchial delivery. Although AAV6, 8, and 9 showed improved transduction of the airway epithelium, there were still physical barriers (such as mucus) and local specific and nonspecific immune responses that acted to prevent airway gene transfer (127, 128).

An alternative route to overcome the barriers to AAV AAT vector delivery to the lung via the respiratory epithelium is to target the lung pleura (136, 137). The pleura presents several structural advantages that make it an attractive site for gene delivery targeting both the lung parenchyma and the systemic circulation, providing a large surface area for gene transfer that is easily accessible. The pleura is a thin serous membrane that encloses the chest cavity, attaching to the chest wall (parietal pleura) and to the lung parenchyma (visceral pleura), and merging at the chest hilum (138, 139). The parietal and visceral pleura contain a single layer of mesothelial cells surrounded by a thin layer of connective tissue rich in lymphatic and blood vessels connected to the systemic circulation (Figure 4A). The pleura layers are separated by a pleural fluid (0.5 to 1 ml in humans) that contains proteins that diffuse from blood and are secreted locally (139–144). Mesothelial cells produce connective tissue components and secrete a variety of other proteins including, within others, pro- and antiinflammatory chemokines and cytokines, growth factors, components of the complement system, prostaglandins, and prostacyclin (139–141, 143).

The intrapleural strategy combines local lung delivery (via the genetically modified mesothelial cells lining the pleura) and systemic delivery (by vector leaking from the pleura via visceral pleural lymphatics to the systemic venous system and then primarily to liver hepatocytes) (Figure 4B). Regarding pleural mesothelial cells, it is likely than AAV-transduced cells will secrete the AAT protein into both the pleural space and the lung interstitium via the basal lateral surface (145). Pleural mesothelial cells have features consistent with active protein transcellular transport (146); AAT produced by the genetically modified pleura mesothelium is likely transported to the lung parenchyma in a mechanism similar to that reported for AAT transcytosis by lung epithelial cells (147). There may also be a contribution from AAT carried by abundant lymphatic vessels from the visceral pleura that form an intercommunicating plexus that penetrates the lungs, draining into the bronchial lymphatics (138, 139, 148). In the case of parietal pleura, the lymphatic system connects directly to the pleural space through stomata, a mechanism for systemic distribution of the gene therapy vector to primarily the liver after intrapleural delivery (Figure 4A) (138, 139, 148). Another advantage of targeting the pleura for gene therapy is the low risk of adverse effects of any inflammation induced by the gene therapy vector, as demonstrated in a safety and toxicology study (149).

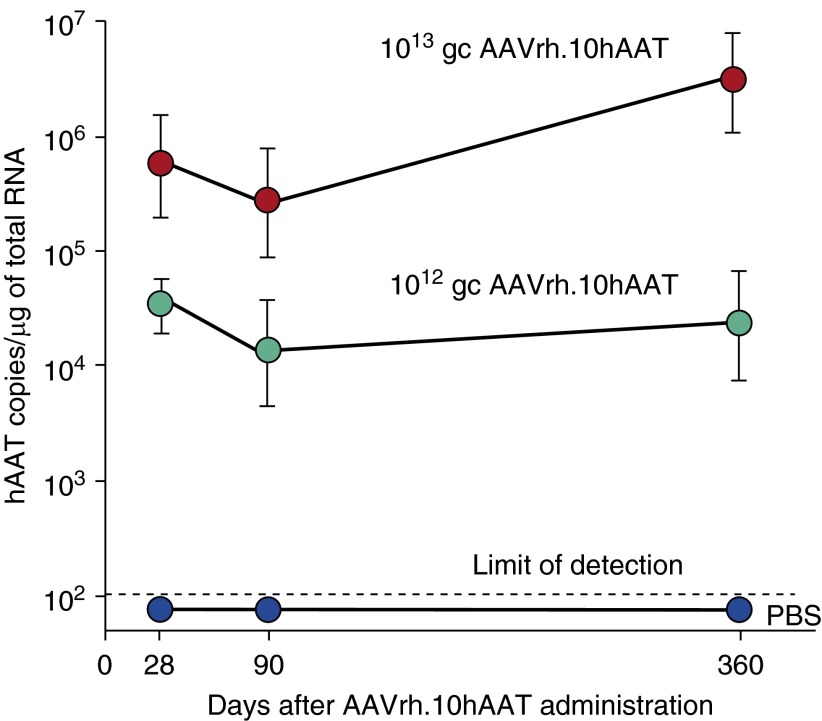

In a mouse preclinical model, De and colleagues (45) demonstrated that an AAV5-based vector expressing human AAT produced high, sustained levels of the protein (1 mg/ml) in serum via the intrapleural route compared with intramuscular administration at the same dose. The therapy approach resulted in levels of AAT in the lung similar to that in serum (45). In a comparison of 25 different AAV serotypes in mice, De and colleagues (46) demonstrated that an AAV nonhuman primate-derived serotype rh.10 (AAVrh.10) vector was the most effective, with intrapleural administration providing high, long-term delivery of human normal M-type AAT (Figure 5A). AAVrh.10 is derived from the rhesus macaque, and therefore, preexisting antivector immunity in humans is minimal. In this study of AAV serotypes (16 nonhuman primate and 9 human AAV serotypes, all using the AAV2 inverted terminal repeats), the AAVrh.10 vector expressed the highest AAT serum levels (2.5-fold above the therapeutic threshold of 11 μM). Of the other serotypes, 13 were derived from rhesus macaques (AAV7, AAV8, AAVrh.2, AAVrh.8, AAVrh.10, AAVrh.13, AAVrh.16, AAVrh.20, AAVrh.21, AAVrh.22, AAVrh.24, AAVrh.34, and AAVrh.43), 1 was derived from cynomolgus macaque (AAVcy.5), 1 from baboon (AAVbb.2), 1 from chimpanzee (AAVch.5), and 9 from humans (AAV2, AAV5, AAV9, AAVhu.1, AAVhu.11, AAVhu.13, AAVhu.37, AAVhu.41, and AAVhu.47) (Figure 5A). The high serum levels were sustained through 24 weeks, the latest point of the study (Figure 5B), and translated to similar therapeutic levels in ELF (Figure 5C). Importantly, similar levels were achieved in serum lung ELF, demonstrating “biochemical efficacy.” In a safety and toxicology study, the AAVrh.10 delivered by the intrapleural route was shown to be safe in studies with 280 mice and 36 nonhuman primates (149). The intrapleural vector transfer resulted in high levels of human AAT messenger RNA localized to the proximity of the lung that persisted for at least 6 months in mice (149) and for at least 1 year after a single vector administration in nonhuman primates (149), the entire length of the study (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Human alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) mRNA expression in the pleura of nonhuman primates 1 year after a single intrapleural AAVrh.10hAAT vector administration. Human AAT mRNA expression was assayed in tissue sections by TaqMan quantitative polymerase chain reaction at 28, 90, and 360 days after single intrapleural administration of phosphate-buffered saline or AAVrh.10hAAT (1012 or 1013 gc) (n = 4 per dose). mRNA copies were normalized per microgram of total RNA. Data are presented as the geometric mean ± SE. gc = genome copies; mRNA = messenger RNA.

The preclinical safety and efficacy studies with the AAVrh.10 vector supported the FDA approval for a phase I/II clinical trial Investigational New Drug (IND) application. The aim of the clinical trial (NCT02168686) is to assess the hypothesis that a single intrapleural administration of a serotype AAVrh.10 vector expressing the normal M1-type AAT (AAVrh.10hAAT) to individuals with AAT deficiency is safe and results in persistent therapeutic serum and alveolar ELF levels of AAT (150). The study will compare two doses, 8 × 1012 and 8 × 1013 genome copy, administered to individuals (n = 5) with a ZZ or Z null genotype and serum AAT levels of less than 11 μM. Individuals will receive the vector as one 50-ml dose, administered directly into the intrapleural space using a needle attached to a central line catheter, and fluoroscopic guidance. As a comparator to the intrapleural route, five individuals with AAT deficiency will be administered the AAVrh.10hAAT vector at each dose level by the intravenous route. In addition to the normal safety parameters, the goal of the therapy will be to reach a sustained concentration of more than 1.2 μM AAT in ELF, the lung “protective level” (150). The completion of this study will provide critical safety and preliminary efficacy data to determine whether to proceed to a phase II/III efficacy study for eventual FDA approval.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank N. Mohamed for help in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported in part by U01 HL66952.

Author Contributions: M.J.C. reviewed the literature and drafted the review paper. M.J.C. and R.G.C. wrote the different sections. R.G.C. critically reviewed and edited the paper.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Gadek JE, Fells GA, Zimmerman RL, Rennard SI, Crystal RG. Antielastases of the human alveolar structures. Implications for the protease-antiprotease theory of emphysema. J Clin Invest. 1981;68:889–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI110344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrell R, Boswell D.Serpins: the superfamily of plasma serine protease inhibitors Barrett A, Salvensen G.Proteinase inhibitorsAmsterdam: Elsevier; 1986403–420. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brantly M, Nukiwa T, Crystal RG. Molecular basis of alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Med. 1988;84:13–31. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brantly ML, Paul LD, Miller BH, Falk RT, Wu M, Crystal RG. Clinical features and history of the destructive lung disease associated with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency of adults with pulmonary symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:327–336. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crystal RG. Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency, emphysema, and liver disease: genetic basis and strategies for therapy. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1343–1352. doi: 10.1172/JCI114578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lungarella G, Cavarra E, Lucattelli M, Martorana PA. The dual role of neutrophil elastase in lung destruction and repair. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1287–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverman EK, Sandhaus RA. Clinical practice: alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2749–2757. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0900449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duranton J, Bieth JG. Inhibition of proteinase 3 by [alpha]1-antitrypsin in vitro predicts very fast inhibition in vivo. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:57–61. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0258OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spencer LT, Paone G, Krein PM, Rouhani FN, Rivera-Nieves J, Brantly ML. Role of human neutrophil peptides in lung inflammation associated with alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L514–L520. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00099.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrache I, Fijalkowska I, Medler TR, Skirball J, Cruz P, Zhen L, Petrache HI, Flotte TR, Tuder RM. Alpha-1 antitrypsin inhibits caspase-3 activity, preventing lung endothelial cell apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1155–1166. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janciauskiene SM, Nita IM, Stevens T. Alpha1-antitrypsin, old dog, new tricks. Alpha1-antitrypsin exerts in vitro anti-inflammatory activity in human monocytes by elevating cAMP. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8573–8582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607976200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergin DA, Reeves EP, Meleady P, Henry M, McElvaney OJ, Carroll TP, Condron C, Chotirmall SH, Clynes M, O’Neill SJ, et al. α-1 Antitrypsin regulates human neutrophil chemotaxis induced by soluble immune complexes and IL-8. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4236–4250. doi: 10.1172/JCI41196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahaf G, Moser H, Ozeri E, Mizrahi M, Abecassis A, Lewis EC. α-1-Antitrypsin gene delivery reduces inflammation, increases T-regulatory cell population size and prevents islet allograft rejection. Mol Med. 2011;17:1000–1011. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis EC. Expanding the clinical indications for α(1)-antitrypsin therapy. Mol Med. 2012;18:957–970. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonigk D, Al-Omari M, Maegel L, Müller M, Izykowski N, Hong J, Hong K, Kim SH, Dorsch M, Mahadeva R, et al. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties of α1-antitrypsin without inhibition of elastase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:15007–15012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309648110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergin DA, Reeves EP, Hurley K, Wolfe R, Jameel R, Fitzgerald S, McElvaney NG. The circulating proteinase inhibitor α-1 antitrypsin regulates neutrophil degranulation and autoimmunity. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:217ra1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehlers MR. Immune-modulating effects of alpha-1 antitrypsin. Biol Chem. 2014;395:1187–1193. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geraghty P, Eden E, Pillai M, Campos M, McElvaney NG, Foronjy RF. α1-Antitrypsin activates protein phosphatase 2A to counter lung inflammatory responses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1229–1242. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201405-0872OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyot N, Wartelle J, Malleret L, Todorov AA, Devouassoux G, Pacheco Y, Jenne DE, Belaaouaj A. Unopposed cathepsin G, neutrophil elastase, and proteinase 3 cause severe lung damage and emphysema. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:2197–2210. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaner Z, Ochayon DE, Shahaf G, Baranovski BM, Bahar N, Mizrahi M, Lewis EC. Acute phase protein α1-antitrypsin reduces the bacterial burden in mice by selective modulation of innate cell responses. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:1489–1498. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinden NJ, Baker MJ, Smith DJ, Kreft JU, Dafforn TR, Stockley RA. α-1-Antitrypsin variants and the proteinase/antiproteinase imbalance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L179–L190. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00179.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuder RM, Janciauskiene SM, Petrache I. Lung disease associated with alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:381–386. doi: 10.1513/pats.201002-020AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alam S, Li Z, Janciauskiene S, Mahadeva R. Oxidation of Z α1-antitrypsin by cigarette smoke induces polymerization: a novel mechanism of early-onset emphysema. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:261–269. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0328OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lockett AD, Van Demark M, Gu Y, Schweitzer KS, Sigua N, Kamocki K, Fijalkowska I, Garrison J, Fisher AJ, Serban K, et al. Effect of cigarette smoke exposure and structural modifications on the α-1 antitrypsin interaction with caspases. Mol Med. 2012;18:445–454. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alam S, Li Z, Atkinson C, Jonigk D, Janciauskiene S, Mahadeva R. Z α1-antitrypsin confers a proinflammatory phenotype that contributes to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:909–931. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1458OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crystal RG, Brantly ML, Hubbard RC, Curiel DT, States DJ, Holmes MD Clinical Consequences and Strategies for Therapy. The alpha 1-antitrypsin gene and its mutations: clinical consequences and strategies for therapy. Chest. 1989;95:196–208. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.1.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficiency Registry Study Group. Survival and FEV1 decline in individuals with severe deficiency of alpha1-antitrypsin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:49–59. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9712017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lomas DA, Parfrey H. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. 4: molecular pathophysiology. Thorax. 2004;59:529–535. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.006528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanash HA, Nilsson PM, Nilsson JA, Piitulainen E. Survival in severe alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency (PiZZ) Respir Res. 2010;11:44. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Serres FJ, Blanco I. Prevalence of α1-antitrypsin deficiency alleles PI*S and PI*Z worldwide and effective screening for each of the five phenotypic classes PI*MS, PI*MZ, PI*SS, PI*SZ, and PI*ZZ: a comprehensive review. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2012;6:277–295. doi: 10.1177/1753465812457113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perlmutter DH, Silverman GA. Hepatic fibrosis and carcinogenesis in α1-antitrypsin deficiency: a prototype for chronic tissue damage in gain-of-function disorders. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a005801. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Topic A, Ljujic M, Radojkovic D. Alpha-1-antitrypsin in pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepat Mon. 2012;12:e7042. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.7042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inaty H, Arabelovic S. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in a patient diagnosed with granulomatosis with polyangiitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Teckman JH. Liver disease in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: current understanding and future therapy. COPD. 2013;10:35–43. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2013.765839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alberici F, Martorana D, Vaglio A. Genetic aspects of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:i37–i45. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Serres F, Blanco I. Role of alpha-1 antitrypsin in human health and disease. J Intern Med. 2014;276:311–335. doi: 10.1111/joim.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stone H, Pye A, Stockley RA. Disease associations in alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Respir Med. 2014;108:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duvoix A, Roussel BD, Lomas DA. Molecular pathogenesis of alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Rev Mal Respir. 2014;31:992–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wewers MD, Casolaro MA, Sellers SE, Swayze SC, McPhaul KM, Wittes JT, Crystal RG. Replacement therapy for alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency associated with emphysema. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1055–1062. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704233161704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hubbard RC, Sellers S, Czerski D, Stephens L, Crystal RG. Biochemical efficacy and safety of monthly augmentation therapy for alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. JAMA. 1988;260:1259–1264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hubbard RC, Crystal RG. Augmentation therapy of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Eur Respir J Suppl. 1990;9:44s–52s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenfeld MA, Siegfried W, Yoshimura K, Yoneyama K, Fukayama M, Stier LE, Pääkkö PK, Gilardi P, Stratford-Perricaudet LD, Perricaudet M, et al. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of a recombinant alpha 1-antitrypsin gene to the lung epithelium in vivo. Science. 1991;252:431–434. doi: 10.1126/science.2017680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: standards for the diagnosis and management of individuals with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:818–900. doi: 10.1164/rccm.168.7.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gadek JE, Klein HG, Holland PV, Crystal RG. Replacement therapy of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Reversal of protease-antiprotease imbalance within the alveolar structures of PiZ subjects. J Clin Invest. 1981;68:1158–1165. doi: 10.1172/JCI110360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De B, Heguy A, Leopold PL, Wasif N, Korst RJ, Hackett NR, Crystal RG. Intrapleural administration of a serotype 5 adeno-associated virus coding for alpha1-antitrypsin mediates persistent, high lung and serum levels of alpha1-antitrypsin. Mol Ther. 2004;10:1003–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De BP, Heguy A, Hackett NR, Ferris B, Leopold PL, Lee J, Pierre L, Gao G, Wilson JM, Crystal RG. High levels of persistent expression of alpha1-antitrypsin mediated by the nonhuman primate serotype rh.10 adeno-associated virus despite preexisting immunity to common human adeno-associated viruses. Mol Ther. 2006;13:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flotte TR, Trapnell BC, Humphries M, Carey B, Calcedo R, Rouhani F, Campbell-Thompson M, Yachnis AT, Sandhaus RA, McElvaney NG, et al. Phase 2 clinical trial of a recombinant adeno-associated viral vector expressing α1-antitrypsin: interim results. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:1239–1247. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo S, Booten SL, Watt A, Alvarado L, Freier SM, Teckman JH, McCaleb ML, Monia BP. Using antisense technology to develop a novel therapy for α-1 antitrypsin deficient (AATD) liver disease and to model AATD lung disease. Rare Dis. 2014;2:e28511. doi: 10.4161/rdis.28511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stockley RA, Turner AM. α-1-Antitrypsin deficiency: clinical variability, assessment, and treatment. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teckman JH, Jain A. Advances in alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency liver disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16:367. doi: 10.1007/s11894-013-0367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Perlmutter DH. Targeting intracellular degradation pathways for treatment of liver disease caused by α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Pediatr Res. 2014;75:133–139. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greene CM, Miller SD, Carroll T, McLean C, O’Mahony M, Lawless MW, O’Neill SJ, Taggart CC, McElvaney NG. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: a conformational disease associated with lung and liver manifestations. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:21–34. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0748-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mornex JF, Chytil-Weir A, Martinet Y, Courtney M, LeCocq JP, Crystal RG. Expression of the alpha-1-antitrypsin gene in mononuclear phagocytes of normal and alpha-1-antitrypsin-deficient individuals. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:1952–1961. doi: 10.1172/JCI112524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van ’t Wout EF, van Schadewijk A, Savage ND, Stolk J, Hiemstra PS. α1-antitrypsin production by proinflammatory and antiinflammatory macrophages and dendritic cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46:607–613. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0231OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.du Bois RM, Bernaudin JF, Paakko P, Hubbard R, Takahashi H, Ferrans V, Crystal RG. Human neutrophils express the alpha 1-antitrypsin gene and produce alpha 1-antitrypsin. Blood. 1991;77:2724–2730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Venembre P, Boutten A, Seta N, Dehoux MS, Crestani B, Aubier M, Durand G. Secretion of alpha 1-antitrypsin by alveolar epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1994;346:171–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80695-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cichy J, Potempa J, Travis J. Biosynthesis of alpha1-proteinase inhibitor by human lung-derived epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8250–8255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geboes K, Ray MB, Rutgeerts P, Callea F, Desmet VJ, Vantrappen G. Morphological identification of alpha-I-antitrypsin in the human small intestine. Histopathology. 1982;6:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1982.tb02701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perlmutter DH, Daniels JD, Auerbach HS, De Schryver-Kecskemeti K, Winter HS, Alpers DH. The alpha 1-antitrypsin gene is expressed in a human intestinal epithelial cell line. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:9485–9490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cox DW, Markovic VD, Teshima IE. Genes for immunoglobulin heavy chains and for alpha 1-antitrypsin are localized to specific regions of chromosome 14q. Nature. 1982;297:428–430. doi: 10.1038/297428a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schroeder WT, Miller MF, Woo SL, Saunders GF. Chromosomal localization of the human alpha 1-antitrypsin gene (PI) to 14q31-32. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:868–872. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laurell C-B, Eriksson S. The electrophoretic alpha1-globulin pattern of serum in alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1963;15:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seixas S, Garcia O, Trovoada MJ, Santos MT, Amorim A, Rocha J. Patterns of haplotype diversity within the serpin gene cluster at 14q32.1: insights into the natural history of the alpha1-antitrypsin polymorphism. Hum Genet. 2001;108:20–30. doi: 10.1007/s004390000434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stoller JK, Aboussouan LS. A review of α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:246–259. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1428CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kurachi K, Chandra T, Degen SJ, White TT, Marchioro TL, Woo SL, Davie EW. Cloning and sequence of cDNA coding for alpha 1-antitrypsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6826–6830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jeppsson JO. Amino acid substitution Glu leads to Lys alpha1-antitrypsin PiZ. FEBS Lett. 1976;65:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80478-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Birrer P, McElvaney NG, Chang-Stroman LM, Crystal RG. Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency and liver disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1991;14:512–525. doi: 10.1007/BF01797921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gooptu B, Lomas DA. Conformational pathology of the serpins: themes, variations, and therapeutic strategies. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:147–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082107.133320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lomas DA, Evans DL, Finch JT, Carrell RW. The mechanism of Z alpha 1-antitrypsin accumulation in the liver. Nature. 1992;357:605–607. doi: 10.1038/357605a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nukiwa T, Satoh K, Brantly ML, Ogushi F, Fells GA, Courtney M, Crystal RG. Identification of a second mutation in the protein-coding sequence of the Z type alpha 1-antitrypsin gene. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15989–15994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Long GL, Chandra T, Woo SL, Davie EW, Kurachi K. Complete sequence of the cDNA for human alpha 1-antitrypsin and the gene for the S variant. Biochemistry. 1984;23:4828–4837. doi: 10.1021/bi00316a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Owen MC, Carrell RW, Brennan SO. The abnormality of the S variant of human alpha-1-antitrypsin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;453:257–261. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(76)90271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoshida A, Ewing C, Wessels M, Lieberman J, Gaidulis L. Molecular abnormality of PI S variant of human alpha1-antitrypsin. Am J Hum Genet. 1977;29:233–239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ogushi F, Hubbard RC, Fells GA, Casolaro MA, Curiel DT, Brantly ML, Crystal RG. Evaluation of the S-type of alpha-1-antitrypsin as an in vivo and in vitro inhibitor of neutrophil elastase. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:364–370. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bornhorst JA, Greene DN, Ashwood ER, Grenache DG. α1-Antitrypsin phenotypes and associated serum protein concentrations in a large clinical population. Chest. 2013;143:1000–1008. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.American Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the approach to the patient with severe hereditary alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:1494–1497. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.5.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Marciniuk DD, Hernandez P, Balter M, Bourbeau J, Chapman KR, Ford GT, Lauzon JL, Maltais F, O’Donnell DE, Goodridge D, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society COPD Clinical Assembly Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency Expert Working Group. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency targeted testing and augmentation therapy: a Canadian Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Can Respir J. 2012;19:109–116. doi: 10.1155/2012/920918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chapman KR, Burdon JG, Piitulainen E, Sandhaus RA, Seersholm N, Stocks JM, Stoel BC, Huang L, Yao Z, Edelman JM, et al. RAPID Trial Study Group. Intravenous augmentation treatment and lung density in severe α1 antitrypsin deficiency (RAPID): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:360–368. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60860-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thompson Healthcare. 2010. Red book: pharmacy's fundamental reference. Montavale, NJ: Thomson Reuters PDR Network.

- 80.Garver RI, Jr, Chytil A, Courtney M, Crystal RG. Clonal gene therapy: transplanted mouse fibroblast clones express human alpha 1-antitrypsin gene in vivo. Science. 1987;237:762–764. doi: 10.1126/science.3497452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Song S, Embury J, Laipis PJ, Berns KI, Crawford JM, Flotte TR. Stable therapeutic serum levels of human alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) after portal vein injection of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1299–1306. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kay MA, Baley P, Rothenberg S, Leland F, Fleming L, Ponder KP, Liu T, Finegold M, Darlington G, Pokorny W, et al. Expression of human alpha 1-antitrypsin in dogs after autologous transplantation of retroviral transduced hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:89–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kay MA, Li Q, Liu TJ, Leland F, Toman C, Finegold M, Woo SL. Hepatic gene therapy: persistent expression of human alpha 1-antitrypsin in mice after direct gene delivery in vivo. Hum Gene Ther. 1992;3:641–647. doi: 10.1089/hum.1992.3.6-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kolodka TM, Finegold M, Kay MA, Woo SL. Hepatic gene therapy: efficient retroviral-mediated gene transfer into rat hepatocytes in vivo. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1993;19:491–497. doi: 10.1007/BF01233254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Saylors RL, III, Wall DA. Expression of human alpha 1 antitrypsin in murine hematopoietic cells in vivo after retrovirus-mediated gene transfer. Mol Genet Metab. 1998;63:198–204. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1997.2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bou-Gharios G, Wells DJ, Lu QL, Morgan JE, Partridge T. Differential expression and secretion of alpha 1 anti-trypsin between direct DNA injection and implantation of transfected myoblast. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1021–1029. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang G, Song YK, Liu D. Long-term expression of human alpha1-antitrypsin gene in mouse liver achieved by intravenous administration of plasmid DNA using a hydrodynamics-based procedure. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1344–1349. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hickman MA, Malone RW, Lehmann-Bruinsma K, Sih TR, Knoell D, Szoka FC, Walzem R, Carlson DM, Powell JS. Gene expression following direct injection of DNA into liver. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:1477–1483. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.12-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Aliño SF, Crespo A, Dasí F. Long-term therapeutic levels of human alpha-1 antitrypsin in plasma after hydrodynamic injection of nonviral DNA. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1672–1679. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen ZY, Yant SR, He CY, Meuse L, Shen S, Kay MA. Linear DNAs concatemerize in vivo and result in sustained transgene expression in mouse liver. Mol Ther. 2001;3:403–410. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Canonico AE, Plitman JD, Conary JT, Meyrick BO, Brigham KL. No lung toxicity after repeated aerosol or intravenous delivery of plasmid-cationic liposome complexes. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1994;77:415–419. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.1.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Canonico AE, Conary JT, Meyrick BO, Brigham KL. Aerosol and intravenous transfection of human alpha 1-antitrypsin gene to lungs of rabbits. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10:24–29. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.1.8292378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dasí F, Benet M, Crespo J, Crespo A, Aliño SF. Asialofetuin liposome-mediated human alpha1-antitrypsin gene transfer in vivo results in stationary long-term gene expression. J Mol Med (Berl) 2001;79:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s001090000185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]