Abstract

Rationale: Among individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), depression is one of the most common yet underrecognized and undertreated comorbidities. Although depression has been associated with reduced adherence to maintenance medications used in other conditions, such as diabetes, little research has assessed the role of depression in COPD medication use and adherence.

Objectives: The objective of this study was to assess the impact of depression on COPD maintenance medication adherence among a nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with COPD.

Methods: We used a 5% random sample of Medicare administrative claims data to identify beneficiaries diagnosed with COPD between 2006 and 2010. We included beneficiaries with 2 years of continuous Medicare Parts A, B, and D coverage and at least two prescription fills for COPD maintenance medications after COPD diagnosis. We searched for prescription fills for inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting β-agonists, and long-acting anticholinergics and calculated adherence starting at the first fill. We modeled adherence to COPD maintenance medications as a function of new episodes of depression, using generalized estimated equations.

Measurements and Main Results: Our primary outcome was adherence to COPD maintenance medications, measured as proportion of days covered. The exposure measure was depression. Both COPD and depression were assessed using diagnostic codes in Part A and B data. Covariates included sociodemographics, as well as clinical markers, including comorbidities, COPD severity, and depression severity. Of 31,033 beneficiaries meeting inclusion criteria, 6,227 (20%) were diagnosed with depression after COPD diagnosis. Average monthly adherence to COPD maintenance medications was low, peaking at 57% in the month after first fill and decreasing to 35% within 6 months. In our adjusted regression model, depression was associated with decreased adherence to COPD maintenance medications (odds ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.89–0.98).

Conclusions: New episodes of depression decreased adherence to maintenance medications used to manage COPD among older adults. Clinicians who treat older adults with COPD should be aware of the development of depression, especially during the first 6 months after COPD diagnosis, and monitor patients’ adherence to prescribed COPD medications to ensure best clinical outcomes.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, adherence

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic lower respiratory disease characterized by obstruction of airflow. COPD is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and the third leading cause of death in the United States (1, 2). Although smoking is the most common risk factor for the development of COPD in the United States, environmental exposures and genetics also play a role (1, 3). In 2010, medical costs of COPD in the United States were estimated at $36 billion and projected to reach $49 billion by 2020 (4).

Clinicians select pharmacologic strategies used for the management of COPD based on COPD severity to reduce symptoms and prevent COPD exacerbations (1). Maintenance medications, including inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting β-agonists, and long-acting anticholinergics, have been shown to reduce exacerbations and improve lung function and health-related quality of life among patients with moderate to severe disease (5–7). Nonetheless, use of and adherence to COPD maintenance medications remain low, ranging from 29 to 56%, and contribute to increased hospitalization, health care costs, and mortality (8–20).

Among patients with COPD, depression remains one of the most common, yet least recognized and undertreated, comorbidities, with a prevalence of 17–44% (21–27). Depression has been associated with decreased adherence to maintenance medications used in chronic conditions such as diabetes (28, 29). Few studies have assessed the association between depression and adherence to COPD medications, and these were limited by a cross-sectional study design (30, 31). The objective of this study was to assess the impact of depression on COPD maintenance medication adherence among a nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with COPD. We hypothesize that new episodes of depression will result in decreased adherence to COPD maintenance medications.

Methods

Study Population

We obtained Medicare administrative claims data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Chronic Condition Data Warehouse (CCW) for a 5% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries from 2006 to 2012. We identified beneficiaries with at least one inpatient or outpatient claim containing the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) for COPD (code 490, 491.x, 492.x, 494.x, or 496), and excluded beneficiaries with a history of respiratory cancer, tuberculosis, asbestosis, and sarcoidosis because their medication use may differ from that of other individuals with COPD. These ICD-9-CM codes are used by the CMS to identify beneficiaries with COPD and have a positive predictive value of 73% (32). We required continuous Medicare Parts A, B, D, and no Part C coverage for 24 months after initial diagnosis of COPD (index date) during the study period to ensure adequate follow-up. All Medicare beneficiaries who met criteria for COPD since 1999 have the date of first diagnosis of COPD reported in the CMS Master Beneficiary Summary File. We used this date to exclude beneficiaries whose first diagnosis of COPD occurred before the study period (2006–2012). We required that study participants have at least two prescription fills of a maintenance medication during the 24-month follow-up period.

Exposure

We used ICD-9-CM codes 296.2x, 296.3x, and 311.xx to define depression. These codes have been used previously and exclude bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and dysthymic disorder (33–35). Presence of depression was defined as at least one diagnosis code on at least one inpatient claim or at least two outpatient claims during the study period. To increase identification of beneficiaries with depression, we also accepted evidence of at least one antidepressant prescription fill in conjunction with diagnosis of depression on one outpatient claim. Information on antidepressant fills was collected from Part D prescription drug event files.

Depression is a chronic disorder that occurs as one or more unique episodes and could be diagnosed at any time during the study period (36, 37). We were interested in how new episodes of depression impacted adherence to COPD maintenance medications. Therefore, among individuals with depression episodes both before and after COPD diagnosis, we defined a new episode of depression after COPD diagnosis as one occurring more than 5 months after the depression episode before COPD diagnosis.

Outcome

The primary outcome of this study was adherence to inhaled COPD maintenance medications. We searched for all inhaled maintenance medications (inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting β-agonists, long-acting anticholinergics) in the Part D prescription drug events file. We excluded oral methylxanthines because they can be used as either acute or maintenance medications and are limited to severe COPD (37). We divided follow-up time after the COPD index date into 30-day months, and measured adherence using proportion of days covered (PDC) (number of daily doses in the prescription/30 d) for all maintenance medications per month. The PDC ranges from 0 to 1. The PDC is a widely used measure of medication adherence in administrative claims data (38, 39). Adherence was measured monthly from the date of the first fill of a COPD maintenance medication after COPD diagnosis through the end of the study period. We created a rolling 3-month average adherence to reduce variability in monthly adherence measures. Because distribution of this variable was highly skewed, we created adherence categories: <0.2, ≥0.2 to <0.4, ≥0.4 to <0.6, ≥0.6 to <0.8, and ≥0.8.

Covariates

Baseline comorbidities at COPD diagnosis were determined using the CCW 27 flagged comorbid conditions (40). If the date of first diagnosis of a chronic condition was before the date of COPD diagnosis, the patient was considered to have that chronic condition at baseline. We controlled for diagnosis of asthma (ICD-9-CM codes 493.xx on one or more inpatient claims or two or more outpatient claims). We summed indicator variables for chronic conditions including Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, osteoarthritis, stroke, and asthma to create a comorbidity measure. Our measure had a range of 0–9 and was categorized as fewer than two, two or three, and more than three chronic conditions, based on its distribution. We created time-varying comorbidity diagnoses for use in our regression model by comparing the first date of diagnosis with the first day of each month after diagnosis of COPD.

Depression is one of the CCW 27 flagged comorbid conditions. The CCW algorithm differs from our definition by including ICD-9-CM codes 296.5x, 296.6x, 296.89, 298.0, 300.4, and 309.1. We used the CCW depression algorithm to capture individuals with a history of depression before 2006.

To assess severity of depression, we created a variable comprising a count of three measures obtained from inpatient and outpatient claims: the presence of a “4” in the fifth place of an ICD-9-CM code for depression, evidence of psychotherapy or other nonpharmacological treatment, and psychiatric hospitalization with a primary diagnosis of depression. This variable had a range of 0–3 and was dichotomized at 1.

We created a variable indicating any use of short-acting β-agonists and short-acting anticholinergics (COPD acute medications) during the month. We searched for the presence of any nursing home claim on any inpatient stay, or health care common procedure coding system or place of service codes on a skilled nursing facility claim during the month to indicate nursing home stay within the month.

Characteristics suggestive of COPD severity included supplemental oxygen use, COPD-related hospitalization (dichotomized at ≥1 COPD hospital days/mo), and monthly COPD-related emergency department visits (dichotomized at ≥1 emergency department visit/mo) (30, 41, 42). We searched carrier and durable medical equipment claims for the following preventive health services use measures: influenza vaccination, colorectal cancer screening, prostate cancer screening, and mammography and Papanicolaou smears (43). An annual count of preventive health services use measures (including mammography or Papanicolaou test) was created as an indicator of healthy behavior. This variable had a range of 0–3 and, based on its distribution, was dichotomized at 1 or more.

We linked our Medicare cohort to county-level data from the Area Health Resource File. The Area Health Resource File contains health resources and socioeconomic indicators from multiple sources. We abstracted variables representing median household income, percentage of persons aged 25 and older with four or more years of college, percentage of persons aged 25 and older with less than a high school education, and number of primary care providers per 100,000 population.

Data Analysis

Distributions of variables were examined overall and by depression status. For descriptive purposes, we made comparisons between beneficiaries diagnosed with depression at any time during the 24-month follow-up and those who were not, using a χ2 or Student t test as appropriate. We plotted the average 3-month adherence to COPD maintenance medications over time.

We used generalized estimating equations with a multinomial distribution and a cumulative logit link to model the odds of being in a higher adherence category (greater adherence) as a function of our time-varying depression variable and assumed a compound symmetry covariance matrix to estimate the correlations among measurements within an individual. The analyses were conducted at the person-month level. We tested interactions with sex, age, and low-income subsidy a priori. Covariates associated with depression or adherence were considered for inclusion in our model. Comorbidities, acute inhaler use, COPD severity variables, our preventive health measure, and nursing home residence were allowed to vary with time. Covariates resulting in a greater than 10% change to the effect estimate or whose type III P value was less than 0.001 were included in the final model. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported.

To test the assumption of proportionality in our multinomial model, we conducted sensitivity analyses. We created dichotomous variables representing 3-month average adherence at each decile between 0 and 1. We used generalized estimating equations with a binomial distribution and a logit link to model the odds of an observation falling into the higher adherence category and assumed a compound symmetry covariance matrix to estimate the correlations among measurements within an individual. We ran separate models for each decile. Sensitivity analyses included all variables from the final regression model of the main analysis.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Maryland, Baltimore (Baltimore, MD), which waived the requirement for written informed consent. All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Because of our large sample size, a P value less than 0.001 was considered statistically significant in bivariate analysis.

Results

There were 129,606 Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with COPD between 2006 and 2010. Of these, 80,487 (62%) had 24 months of continuous coverage of Medicare Parts A, B, D, and no Part C after COPD diagnosis. Of these, 31,033 (39%) had at least two fills of a COPD maintenance medication, and this group formed our sample population. The average age was 68.4 (SD, 12.2) years (Table 1). The study sample was primarily female (64.8%) and white (83.2%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) between 2006 and 2010 and receiving at least two fills of COPD maintenance medication, by depression status at 24 months of follow-up

| Study Population (n = 31,033) | Depression (n = 9,593) | No Depression (n = 21,440) | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 68.4 (12.2) | 66.9 (14.0) | 68.8 (11.7) | <0.001 |

| Age (yr) categories, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| <65 | 8,469 (27.3) | 2,358 (37.9) | 6,111 (24.6) | |

| 65–74 | 13,128 (42.3) | 1,927 (30.9) | 11,201 (45.2) | |

| 75–84 | 6,545 (21.1) | 1,187 (19.1) | 5,358 (21.6) | |

| >84 | 2,891 (9.3) | 755 (12.1) | 2,136 (8.6) | |

| Female, n (%) | 20,122 (64.8) | 4,654 (74.7) | 15,468 (62.4) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| White | 25,819 (83.2) | 5,266 (84.6) | 20,553 (82.9) | |

| Black | 3,120 (10.1) | 573 (9.2) | 2,547 (10.3) | |

| Hispanic | 881 (2.8) | 229 (3.7) | 652 (2.6) | |

| Other | 1,213 (3.9) | 159 (2.6) | 1,054 (4.2) | |

| COPD index year, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 2006 | 5,155 (16.6) | 939 (15.1) | 4,216 (17.0) | |

| 2007 | 6,035 (19.4) | 1,097 (17.6) | 4,938 (19.9) | |

| 2008 | 6,354 (20.5) | 1,263 (20.3) | 5,091 (20.5) | |

| 2009 | 6,615 (21.3) | 1,328 (21.3) | 5,287 (21.3) | |

| 2010 | 6,874 (22.2) | 1,600 (25.7) | 5,274 (21.3) | |

| Region, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Northeast | 7,979 (25.7) | 1,716 (27.6) | 6,263 (25.2) | |

| Midwest | 5,539 (17.8) | 1,151 (18.5) | 4,388 (17.7) | |

| South | 12,528 (40.4) | 2,513 (40.4) | 10,015 (40.4) | |

| West | 4,958 (16.0) | 839 (13.5) | 4,119 (16.6) | |

| Median household income | <0.001 | |||

| <$39,000 | 6,657 (21.5) | 1,289 (20.7) | 5,368 (21.6) | |

| ≥$39,000 to <$53,000 | 13,836 (44.6) | 3,522 (56.6) | 13,346 (53.8) | |

| ≥$53,000 | 6,238 (20.1) | 1,399 (22.5) | 6,053 (24.4) | |

| Primary care providers per 100,000 | 0.262 | |||

| <49 | 7,420 (23.9) | 1,458 (23.4) | 5,962 (24.0) | |

| ≥49 to <84 | 15,351 (49.5) | 3,061 (49.2) | 12,290 (49.5) | |

| ≥84 | 8,229 (26.5) | 1,699 (27.3) | 6,530 (26.3) | |

| Percentage without a high school diploma | 0.584 | |||

| <11% | 8,297 (26.7) | 1,695 (27.2) | 6,602 (26.6) | |

| 11–18% | 15,108 (48.7) | 3,019 (48.5) | 12,089 (48.7) | |

| >18% | 7,595 (24.5) | 1,504 (24.2) | 6,091 (24.6) | |

| Percentage with ≥4 yr of college | 0.005 | |||

| <17% | 7,624 (24.6) | 1,445 (23.2) | 6,179 (24.9) | |

| ≥17% to <31% | 15,395 (49.6) | 3,192 (51.3) | 12,203 (49.2) | |

| ≥31% | 7,981 (25.7) | 1,581 (25.4) | 6,400 (25.8) | |

| Original reason for Medicare entitlement, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Age | 20,552 (66.2) | 3,444 (55.3) | 17,108 (69.0) | |

| Disability (receipt of SSDI) | 10,140 (32.7) | 2,714 (43.6) | 7,426 (29.9) | |

| ESRD† | 341 (1.1) | 69 (1.1) | 272 (1.1) | |

| Low-income subsidy, n (%) | 16,951 (54.6) | 4,194 (67.4) | 12,757 (51.4) | <0.001 |

| Nursing home residence in month of diagnosis, n (%) | 1,942 (6.3) | 756 (12.1) | 1,186 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| Comorbid medical conditions, n (%) | ||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 969 (3.1) | 228 (3.7) | 741 (3.0) | 0.006 |

| Alzheimer's disease and related disorders | 2,811 (9.1) | 990 (15.9) | 1,821 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 10,677 (34.4) | 2,055 (33.0) | 8,622 (34.8) | 0.009 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4,644 (15.0) | 1,134 (18.2) | 3,510 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| History of depression before 2006 | 7,280 (23.5) | 3,206 (51.5) | 4,074 (16.4) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 9,415 (30.3) | 2,121 (34.1) | 7,294 (29.4) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 8,409 (27.1) | 1,950 (31.3) | 6,459 (26.0) | <0.001 |

| Hip fracture | 678 (2.2) | 212 (3.4) | 466 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 13,034 (42.0) | 2,756 (44.3) | 10,278 (41.4) | 0.027 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis | 12,937 (41.7) | 3,046 (48.9) | 9,891 (39.9) | <0.001 |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack | 3,555 (11.5) | 956 (15.4) | 2,599 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Comorbid conditions,‡ n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| <2 | 13,094 (42.2) | 2,205 (35.4) | 10,889 (43.9) | |

| 2 or 3 | 10,295 (33.2) | 1,993 (32.0) | 8,302 (33.5) | |

| >3 | 7,644 (24.6) | 2,029 (32.6) | 5,615 (22.6) | |

| ≥1 Preventive health measures, n (%) | 3,052 (9.8) | 493 (7.9) | 2,559 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| Depression severity count ≥ 1, n (%) | 1,071 (3.3) | 715 (11.1) | 356 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| COPD severity measures, n (%) | ||||

| Use of acute COPD medication in month | 11,061 (35.6) | 2,310 (37.1) | 8,751 (35.3) | 0.007 |

| Oxygen use in month of diagnosis | 2,633 (8.5) | 607 (9.7) | 2,026 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 COPD-related emergency department visit in month of diagnosis | 1,589 (5.1) | 370 (5.9) | 1,219 (4.9) | 0.001 |

| ≥1 COPD-related hospitalization in month of diagnosis | 1,271 (4.1) | 298 (4.8) | 973 (3.9) | 0.002 |

| Number of COPD maintenance medication fills, mean (SD) | 11.0 (7.8) | 10.5 (7.5) | 11.1 (7.9) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviation: ESRD = end-stage renal disease; SSDI = Social Security disability insurance.

P value from Student t test for age, Wilcoxon rank-sum test for number of medication fills, and χ2 test for categorical variables and reflects differences between depression and no depression.

End-stage renal disease ± disability.

Includes Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, osteoarthritis, stroke, and asthma.

During the 24-month follow-up period, 6,227 (20.1%) beneficiaries were diagnosed with depression (Table 1). Individuals diagnosed with depression were younger than those who were not diagnosed with depression (66.9 [SD, 14.0] yr vs. 68.8 [SD, 11.7] yr; P < 0.001). Depressed beneficiaries were more likely to be female (74.4 vs. 62.4%; P < 0.001), to have more than three comorbid conditions (32.6 vs. 22.6%; P < 0.001), and to have evidence of a nursing home stay (12.1 vs. 4.8%; P < 0.001). Beneficiaries with depression had more severe COPD symptoms in the month of depression diagnosis as evidenced by higher rates of oxygen use (9.7 vs. 8.2%; P < 0.001).

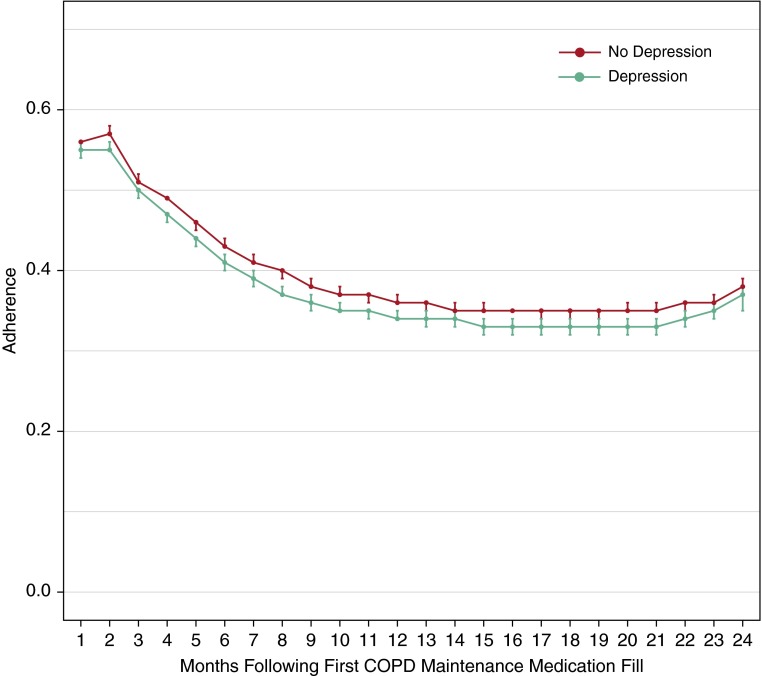

Average monthly adherence to COPD maintenance medications was low, with a peak of 0.57 in the month after the first fill and decreasing rapidly before plateauing at 0.35 by the seventh month (Figure 1). Individuals with depression had lower adherence throughout the study period compared with those without depression. Only 20% of depressed individuals and 22% of nondepressed individuals fell into the highest (>80%) adherence category.

Figure 1.

Average 3-month rolling adherence to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) maintenance medications over time by depression status.

Our adjusted multinomial regression model contained terms for new episode depression, time, COPD index year, age, sex, race, region, percentage of county-level population without a high school diploma, original reason for Medicare entitlement, low-income subsidy, comorbid conditions, acute inhaler use, COPD severity variables, preventive health measures, nursing home residence within the month, and polypharmacy. There was no effect modification by sex, age, or low-income subsidy.

In our adjusted model, a new episode of depression was associated with decreased odds of greater adherence to COPD maintenance medications (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.89–0.98) (Table 2). Acute inhaler use (OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 2.02–2.15), supplemental oxygen use (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.36–1.51), nursing home residence (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.11–1.230), and low-income subsidy (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.27–1.37) were associated with increased adherence to COPD maintenance medications. Our assumption of proportionality was supported.

Table 2.

Adjusted and unadjusted odds of greater adherence to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) maintenance medications among Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with COPD between 2006 and 2010 and receiving at least two fills of COPD maintenance medication over 24 months of follow-up

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|

|

Unadjusted Results | |

| New episode depression | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) |

|

Adjusted Results | |

| New episode depression | 0.93 (0.89–0.98) |

| Time, mo | 0.97 (0.97–0.97) |

| COPD index year | |

| 2006 | Reference |

| 2007 | 1.15 (1.09–1.22) |

| 2008 | 1.16 (1.10–1.23) |

| 2009 | 1.24 (1.17–1.31) |

| 2010 | 1.30 (1.23–1.37) |

| Age, yr | 1.00 (1.00– 1.00) |

| Sex | |

| Male | Reference |

| Female | 0.94 (0.91–0.98) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | Reference |

| Black | 0.80 (0.76–0.85) |

| Hispanic | 0.68 (0.62–0.76) |

| Other | 0.88 (0.91–0.96) |

| Region | |

| Midwest | Reference |

| Northeast | 1.10 (1.05–1.16) |

| South | 0.89 (0.85–0.93) |

| West | 0.95 (0.90–1.01) |

| Percentage of census tract without a high school diploma | |

| <11% | Reference |

| 11–18% | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) |

| >18% | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) |

| Original reason for Medicare entitlement | |

| Age | Reference |

| Disability | 0.85 (0.81–0.90) |

| ESRD* | 0.63 (0.53–0.74) |

| Comorbid medical conditions | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 0.84 (0.78–0.91) |

| Asthma | 1.35 (1.30–1.40) |

| History of depression | 0.81 (0.78–0.85) |

| Diabetes | 0.91 (0.87–0.95) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis | 0.76 (0.74–0.79) |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack | 0.84 (0.79–0.88) |

| Comorbid conditions† | |

| <2 | Reference |

| 2 or 3 | 0.77 (0.74–0.81) |

| >3 | 0.68 (0.64–0.73) |

| Acute inhaler use | 2.08 (2.02–2.15 |

| COPD severity variables | |

| Oxygen use in month of diagnosis | 1.43 (1.36–1.51) |

| ≥1 COPD-related ED visit | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) |

| ≥1 COPD-related hospitalization | 1.33 (1.23–1.44) |

| ≥1 Preventive health measures | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) |

| Nursing home residence | 1.20 (1.11–1.30) |

| Polypharmacy (per medication) | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) |

| Low-income subsidy | 1.32 (1.27–1.37) |

Definition of abbreviation: ED = emergency department; ESRD = end-stage renal disease.

Study population: n = 31,033.

End-stage renal disease ± disability.

Includes Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, osteoarthritis, stroke, and asthma.

Discussion

Beneficiaries with evidence of depression were less likely to adhere to COPD maintenance medications compared with their nondepressed peers. Adherence to COPD maintenance medications falls precipitously within the first 6 months of use, regardless of depression status. Our study results highlight the importance of evaluation and monitoring of depression, as well as the importance of regular follow-up and counseling on medication adherence, to maximize well-being of individuals with COPD. Although our study findings suggest that the first 6 months after COPD diagnosis is a critical time period for medication monitoring, given the chronic and progressive nature of COPD, close attention throughout the disease trajectory may be important.

The association between depression and decreased adherence to COPD medications has been previously reported (31, 41, 42, 44); however, only a single study quantified the effect (30). Qian and colleagues analyzed maintenance medication adherence, using a cross-sectional study design, among Medicare beneficiaries with COPD and reported that individuals with depression were 11% less likely to have high adherence (30). Our study overcame the limitations of the cross-sectional study design by examining the longitudinal association between depression and medication adherence, yet reported results consistent with those of the study by Qian and colleagues (9% less likely to have greater adherence).

Comorbid depression in COPD resulted in decreased adherence, as did the presence of any other comorbid condition (except asthma), suggesting that multimorbidity decreases adherence, possibly through complex medication regimens or patient prioritization of one comorbid illness over another (45). Our results suggest that individuals with more than three chronic conditions are at highest risk of poor adherence. This effect was mitigated by increased severity of COPD symptoms, evidenced by acute inhaler use, oxygen use, and COPD-related hospitalizations, and is consistent with a prior report (30).

Historically, use of and adherence to COPD maintenance medications has been suboptimal, with many individuals with COPD not receiving any maintenance medications (14, 15, 17). Among individuals who use COPD medications, adherence is low, which poses difficulties in medication management (8–18). In this study, we found that only 22% of the sample achieved adherence of at least 80%, regardless of depression status. Our study was conducted among beneficiaries with at least two medication fills over the 24 months after COPD diagnosis, representing those most likely to adhere to COPD medications, as they have documented primary adherence by picking up their COPD medication prescriptions. Nonetheless, the observed drop in adherence after first COPD maintenance medication fill suggests most individuals with COPD are not using medications as prescribed. Although a prior study by Qian and colleagues reported adherence of at least 80% in 36% of Medicare beneficiaries with COPD, it did not assess adherence among patients newly diagnosed with COPD and evaluated adherence from first-filled to last-filled prescription, differences that could account for our lower adherence rate (30). Women were less likely to be adherent to COPD maintenance medications compared with men, which is consistent with two prior studies conducted among individuals with COPD (30, 46). Other studies have not reported a significant association between sex and adherence to COPD medications or medications generally (11, 20, 44, 47). In our study, women composed 65% of the study sample, and 75% of those with depression; hence, residual confounding by depression status is possible. Race was associated with decreased adherence to COPD medications, which is consistent with the study by Qian and colleagues conducted among Medicare beneficiaries with COPD (30).

Limitations and Strengths

As with any study, ours has limitations that should be noted. Our study includes Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with depression; however, depression is underdiagnosed in administrative claims data (48). This potential misclassification of exposure would cause our results to be biased toward the null. In addition, we likely underestimated the burden of depression in COPD by excluding dysthymic disorder and depression found in bipolar and schizoaffective disorder from our depression definition. Furthermore, our adherence measure was based on prescription fills and does not measure actual use of inhaled medications. Finally, we could not control for all confounding or direct influences of medication adherence. For example, future work may consider evaluating the impact of other medications, such as oral corticosteroids, which can mimic psychiatric side effects.

As well, this study has notable strengths. This study is the first to assess adherence to COPD maintenance medications among Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with COPD. In addition, we used a longitudinal study design to capture episodes of diagnosed depression, calculated a rolling monthly adherence value to reduce variance between monthly observations, and treated depression and other covariates as time-varying. Although our data did not include FEV values, a common COPD severity measure, the proxy measures we used for COPD severity (oxygen use, acute inhaler use, hospitalizations) have been used in other studies and correlated with medication adherence in the expected direction (30, 41, 42, 49–51).

Conclusions

Our study found that new episodes of depression have a negative influence on adherence to maintenance medications used to manage COPD among older adults. Clinicians who treat older adults newly diagnosed with COPD should be aware of the development of depression, especially during the first 6 months. As such, clinicians should consider the need to monitor their patients with COPD for need for treatment of depression, as well as use of and adherence to prescribed COPD medications. Close management of these and other aspects of newly diagnosed older adults with COPD will help to ensure optimal clinical outcomes. This study provides foundational work elucidating the association between depression and adherence in older adults with COPD. Future research should consider prospective, longitudinal studies to replicate our findings as well as to further explore the relationship of these comorbid conditions.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant R21AG045573-02 (Simoni-Wastila, PI). J.S.A. is supported by National Institutes of Health grant K12HD43489-13 (Tracey, PI). B.K. is supported by National Institutes of Health grant T32AG000262-14 (Magaziner, PI).

Author Contributions: J.S.A. takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis. L.S.-W. assumes full responsibility for the integrity of the submission as a whole, from inception to published article. Y.P., P.H., T.-Y.H., I.H., G.N., S.W.L., P.L., B.K., Y.-J.W., and P.M. contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. Bethesda, MD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Xu J, Heron M. Deaths: final data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;63:1–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Lung Association. COPD. 2016 [accessed 2015 Oct 9]. Available from: http://www.lung.org/lung-health-and-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/copd/

- 4.Ford ES, Murphy LB, Khavjou O, Giles WH, Holt JB, Croft JB. Total and state-specific medical and absenteeism costs of COPD among adults aged ≥ 18 years in the United States for 2010 and projections through 2020. Chest. 2015;147:31–45. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, Ferguson GT, Jenkins C, Jones PW, Yates JC, Vestbo J TORCH Investigators. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:775–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, Burkhart D, Kesten S, Menjoge S, Decramer M UPLIFT Study Investigators. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1543–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decramer M, Celli B, Kesten S, Lystig T, Mehra S, Tashkin DP UPLIFT Investigators. Effect of tiotropium on outcomes in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (UPLIFT): a prespecified subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawata AK, Kleinman L, Harding G, Ramachandran S. Evaluation of patient preference and willingness to pay for attributes of maintenance medication for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Patient. 2014;7:413–426. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0064-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cecere LM, Slatore CG, Uman JE, Evans LE, Udris EM, Bryson CL, Au DH. Adherence to long-acting inhaled therapies among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) COPD. 2012;9:251–258. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.650241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosley CM, Corden ZM, Rees PJ, Cochrane GM. Psychological factors associated with use of home nebulized therapy for COPD. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:2346–2350. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09112346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolce JJ, Crisp C, Manzella B, Richards JM, Hardin JM, Bailey WC. Medication adherence patterns in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 1991;99:837–841. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.4.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Restrepo RD, Alvarez MT, Wittnebel LD, Sorenson H, Wettstein R, Vines DL, Sikkema-Ortiz J, Gardner DD, Wilkins RL. Medication adherence issues in patients treated for COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:371–384. doi: 10.2147/copd.s3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu AP, Guérin A, Ponce de Leon D, Ramakrishnan K, Wu EQ, Mocarski M, Blum S, Setyawan J. Therapy persistence and adherence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: multiple versus single long-acting maintenance inhalers. J Med Econ. 2011;14:486–496. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.594123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingebrigtsen TS, Marott JL, Nordestgaard BG, Lange P, Hallas J, Dahl M, Vestbo J. Low use and adherence to maintenance medication in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the general population. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:51–59. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3029-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Make B, Dutro MP, Paulose-Ram R, Marton JP, Mapel DW. Undertreatment of COPD: a retrospective analysis of US managed care and Medicare patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:1–9. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S27032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wurst KE, St Laurent S, Mullerova H, Davis KJ. Characteristics of patients with COPD newly prescribed a long-acting bronchodilator: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:1021–1031. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S58258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bender BG. Nonadherence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: what do we know and what should we do next? Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014;20:132–137. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Col N, Fanale JE, Kronholm P. The role of medication noncompliance and adverse drug reactions in hospitalizations of the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:841–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Aymerich J, Barreiro E, Farrero E, Marrades RM, Morera J, Antó JM. Patients hospitalized for COPD have a high prevalence of modifiable risk factors for exacerbation (EFRAM study) Eur Respir J. 2000;16:1037–1042. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16f03.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balkrishnan R, Christensen DB. Inhaled corticosteroid use and associated outcomes in elderly patients with moderate to severe chronic pulmonary disease. Clin Ther. 2000;22:452–469. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)89013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omachi TA, Katz PP, Yelin EH, Gregorich SE, Iribarren C, Blanc PD, Eisner MD. Depression and health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 2009;122:778–e9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jennings JH, Digiovine B, Obeid D, Frank C. The association between depressive symptoms and acute exacerbations of COPD. Lung. 2009;187:128–135. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan VS, Ramsey SD, Giardino ND, Make BJ, Emery CF, Diaz PT, Benditt JO, Mosenifar Z, McKenna R, Jr, Curtis JL, et al. National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) Research Group. Sex, depression, and risk of hospitalization and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2345–2353. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng TP, Niti M, Tan WC, Cao Z, Ong KC, Eng P. Depressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:60–67. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Marco F, Verga M, Reggente M, Maria Casanova F, Santus P, Blasi F, Allegra L, Centanni S. Anxiety and depression in COPD patients: the roles of gender and disease severity. Respir Med. 2006;100:1767–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Manen JG, Bindels PJ, Dekker FW, IJzermans CJ, van der Zee JS, Schadé E. Risk of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its determinants. Thorax. 2002;57:412–416. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.5.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maurer J, Rebbapragada V, Borson S, Goldstein R, Kunik ME, Yohannes AM, Hanania NA ACCP Workshop Panel on Anxiety and Depression in COPD. Anxiety and depression in COPD: current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needs. Chest. 2008;134(4) Suppl:43S–56S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, Rutter C, Simon GE, Oliver M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Bush T, Young B. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2154–2160. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3278–3285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian J, Simoni-Wastila L, Rattinger GB, Zuckerman IH, Lehmann S, Wei YJ, Stuart B. Association between depression and maintenance medication adherence among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:49–57. doi: 10.1002/gps.3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khdour MR, Hawwa AF, Kidney JC, Smyth BM, McElnay JC. Potential risk factors for medication non-adherence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:1365–1373. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh JA. Accuracy of Veterans Affairs databases for diagnoses of chronic diseases. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frayne SM, Miller DR, Sharkansky EJ, Jackson VW, Wang F, Halanych JH, Berlowitz DR, Kader B, Rosen CS, Keane TM. Using administrative data to identify mental illness: what approach is best? Am J Med Qual. 2010;25:42–50. doi: 10.1177/1062860609346347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kramer TL, Owen RR, Cannon D, Sloan KL, Thrush CR, Williams DK, Austen MA. How well do automated performance measures assess guideline implementation for new-onset depression in the Veterans Health Administration? Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(03)29057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith EG, Henry AD, Zhang J, Hooven F, Banks SM. Antidepressant adequacy and work status among Medicaid enrollees with disabilities: a restriction-based, propensity score-adjusted analysis. Community Ment Health J. 2009;45:333–340. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Mueller TI, Endicott J, Coryell W, Hirschfeld RM, Shea T. Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression: a 5-year prospective follow-up of 431 subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:809–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100053010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Shea MT, Warshaw M, Maser JD, Coryell W, Endicott J. Recovery from major depression: a 10-year prospective follow-up across multiple episodes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1001–1006. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, Hudson TJ, West DS, Martin BC. An empirical basis for standardizing adherence measures derived from administrative claims data among diabetic patients. Med Care. 2008;46:1125–1133. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817924d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, Hudson TJ, West DS, Martin BC. Good and poor adherence: optimal cut-point for adherence measures using administrative claims data. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:2303–2310. doi: 10.1185/03007990903126833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Chronic Condition Data Warehouse. Condition categories. 2016 [accessed 2015 Oct 9]. Available from: http://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories.

- 41.Simoni-Wastila L, Wei YJ, Qian J, Zuckerman IH, Stuart B, Shaffer T, Dalal AA, Bryant-Comstock L. Association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease maintenance medication adherence with all-cause hospitalization and spending in a Medicare population. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qian J, Simoni-Wastila L, Langenberg P, Rattinger GB, Zuckerman IH, Lehmann S, Terrin M. Effects of depression diagnosis and antidepressant treatment on mortality in Medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:754–761. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei YJ, Palumbo FB, Simoni-Wastila L, Shulman LM, Stuart B, Beardsley R, Brown CH. Antiparkinson drug adherence and its association with health care utilization and economic outcomes in a Medicare Part D population. Value Health. 2014;17:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bourbeau J, Bartlett SJ. Patient adherence in COPD. Thorax. 2008;63:831–838. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.086041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laforest L, Denis F, Van Ganse E, Ritleng C, Saussier C, Passante N, Devouassoux G, Chatté G, Freymond N, Pacheco Y. Correlates of adherence to respiratory drugs in COPD patients. Prim Care Respir J. 2010;19:148–154. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2010.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krigsman K, Moen J, Nilsson JLG, Ring L. Refill adherence by the elderly for asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease drugs dispensed over a 10-year period. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2007;32:603–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2007.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U, Walkup JT, Akincigil A. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly Medicare population: predictors, disparities, and trends. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1718–1728. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.George J, Kong DCM, Thoman R, Stewart K. Factors associated with medication nonadherence in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;128:3198–3204. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bryant J, McDonald VM, Boyes A, Sanson-Fisher R, Paul C, Melville J. Improving medication adherence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Respir Res. 2013;14:109. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuart BC, Simoni-Wastila L, Zuckerman IH, Davidoff A, Shaffer T, Yang HW, Qian J, Dalal AA, Mapel DW, Bryant-Comstock L. Impact of maintenance therapy on hospitalization and expenditures for Medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8:441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]