Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, numerous genes have been identified by selection from high-copy-number libraries based on "multicopy suppression" or other phenotypic consequences of overexpression. Although fruitful, this approach suffers from two major drawbacks. First, high copy number alone may not permit high-level expression of tightly regulated genes. Conversely, other genes expressed in proportion to dosage cannot be identified if their products are toxic at elevated levels. This work reports construction of a genomic DNA expression library for S. cerevisiae that circumvents both limitations by fusing randomly sheared genomic DNA to the strong, inducible yeast GAL1 promoter, which can be regulated by carbon source. The library obtained contains 5 x 10(7) independent recombinants, representing a breakpoint at every base in the yeast genome. This library was used to examine aberrant gene expression in S. cerevisiae. A screen for dominant activators of yeast mating response identified eight genes that activate the pathway in the absence of exogenous mating pheromone, including one previously unidentified gene. One activator was a truncated STE11 gene lacking approximately 1000 base pairs of amino-terminal coding sequence. In two different clones, the same GAL1 promoter-proximal ATG is in-frame with the coding sequence of STE11, suggesting that internal initiation of translation there results in production of a biologically active, truncated STE11 protein. Thus this library allows isolation based on dominant phenotypes of genes that might have been difficult or impossible to isolate from high-copy-number libraries.

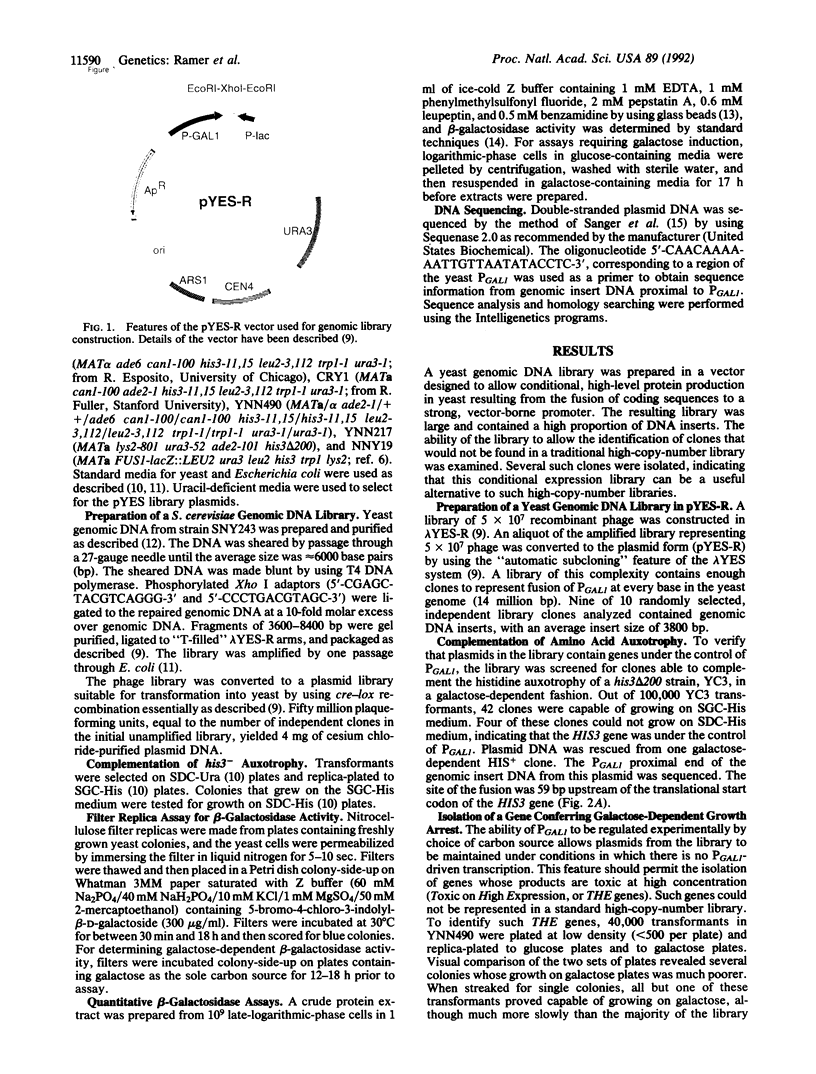

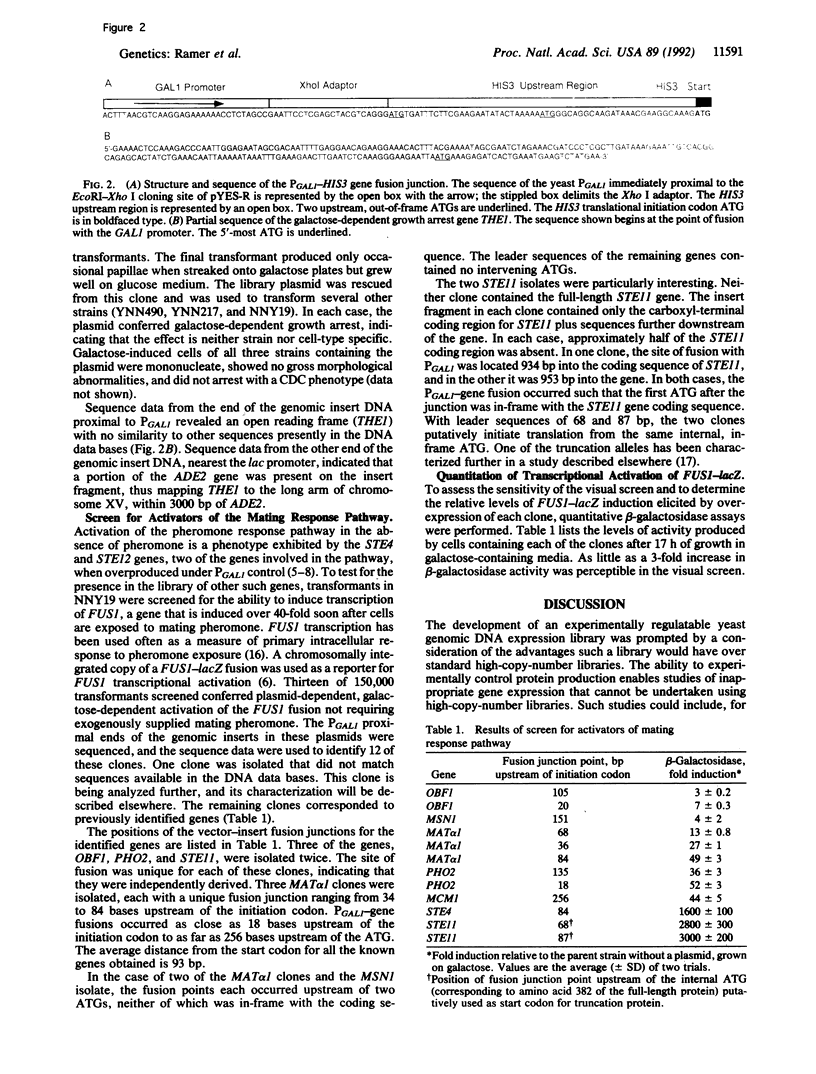

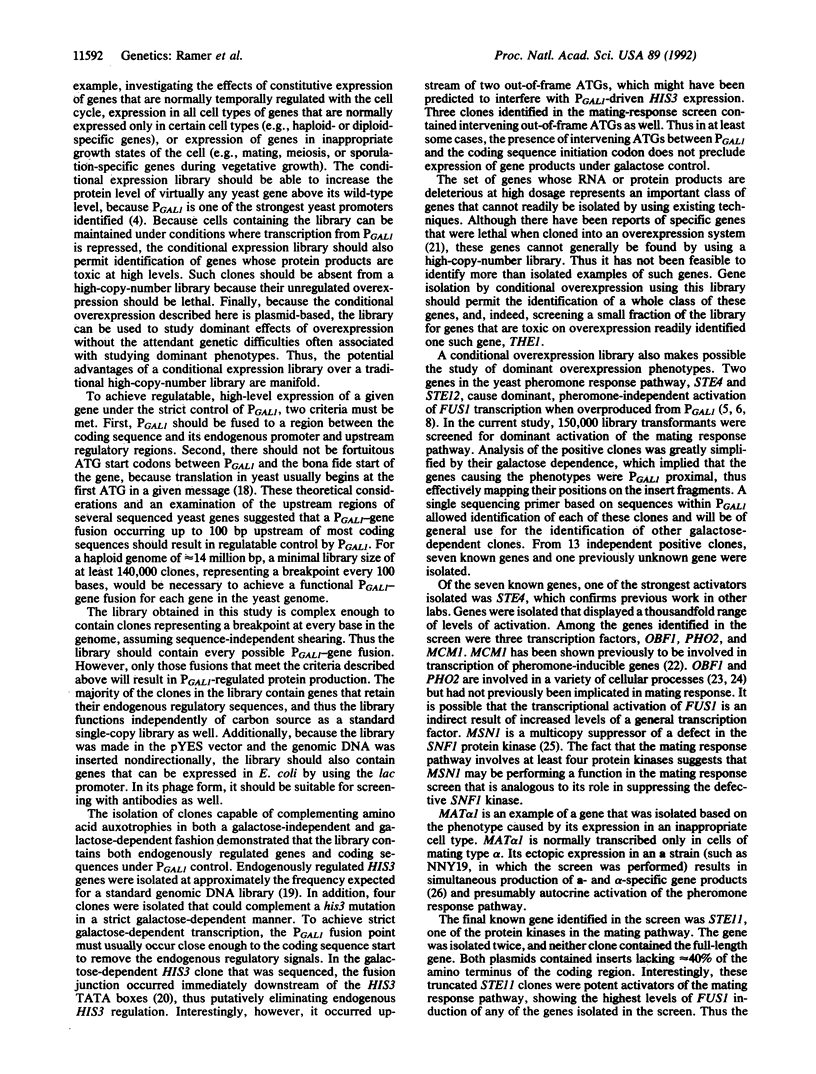

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ammerer G., Sprague G. F., Jr, Bender A. Control of yeast alpha-specific genes: evidence for two blocks to expression in MATa/MAT alpha diploids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Sep;82(17):5855–5859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berben G., Legrain M., Hilger F. Studies on the structure, expression and function of the yeast regulatory gene PHO2. Gene. 1988 Jun 30;66(2):307–312. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke D., Gasdaska P., Hartwell L. Dominant effects of tubulin overexpression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Mar;9(3):1049–1059. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns B. R., Ramer S. W., Kornberg R. D. Order of action of components in the yeast pheromone response pathway revealed with a dominant allele of the STE11 kinase and the multiple phosphorylation of the STE7 kinase. Genes Dev. 1992 Jul;6(7):1305–1318. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigan A. M., Donahue T. F. Sequence and structural features associated with translational initiator regions in yeast--a review. Gene. 1987;59(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke L., Carbon J. A colony bank containing synthetic Col El hybrid plasmids representative of the entire E. coli genome. Cell. 1976 Sep;9(1):91–99. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole G. M., Stone D. E., Reed S. I. Stoichiometry of G protein subunits affects the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mating pheromone signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Feb;10(2):510–517. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan J. W., Fields S. Overproduction of the yeast STE12 protein leads to constitutive transcriptional induction. Genes Dev. 1990 Apr;4(4):492–502. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.4.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elledge S. J., Mulligan J. T., Ramer S. W., Spottswood M., Davis R. W. Lambda YES: a multifunctional cDNA expression vector for the isolation of genes by complementation of yeast and Escherichia coli mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Mar 1;88(5):1731–1735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estruch F., Carlson M. Increased dosage of the MSN1 gene restores invertase expression in yeast mutants defective in the SNF1 protein kinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Dec 11;18(23):6959–6964. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.23.6959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis E. E., Clark K. L., Sprague G. F., Jr The yeast transcription activator PRTF, a homolog of the mammalian serum response factor, is encoded by the MCM1 gene. Genes Dev. 1989 Jul;3(7):936–945. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazwinski S. M. Preparation of extracts from yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:154–174. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82015-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M., Davis R. W. Sequences that regulate the divergent GAL1-GAL10 promoter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Aug;4(8):1440–1448. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.8.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto S., Nakayama N., Arai K., Matsumoto K. Regulation of the yeast pheromone response pathway by G protein subunits. EMBO J. 1990 Mar;9(3):691–696. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippsen P., Stotz A., Scherf C. DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:169–182. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhode P. R., Elsasser S., Campbell J. L. Role of multifunctional autonomously replicating sequence binding factor 1 in the initiation of DNA replication and transcriptional control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Mar;12(3):1064–1077. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rine J., Hansen W., Hardeman E., Davis R. W. Targeted selection of recombinant clones through gene dosage effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Nov;80(22):6750–6754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R. J. One-step gene disruption in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:202–211. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl K. Promoter elements, regulatory elements, and chromatin structure of the yeast his3 gene. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1983;47(Pt 2):901–910. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1983.047.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueheart J., Boeke J. D., Fink G. R. Two genes required for cell fusion during yeast conjugation: evidence for a pheromone-induced surface protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Jul;7(7):2316–2328. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.7.2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivieso M. H., Mol P. C., Shaw J. A., Cabib E., Durán A. CAL1, a gene required for activity of chitin synthase 3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1991 Jul;114(1):101–109. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteway M., Hougan L., Thomas D. Y. Overexpression of the STE4 gene leads to mating response in haploid Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Jan;10(1):217–222. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]