Abstract

Background

Breast density, the amount of fibroglandular tissue in the adult breast for a women’s age and body mass index, is a strong biomarker of susceptibility to breast cancer, which may, like breast cancer risk itself, be influenced by events early in life. In the present study, we investigated the association between pre-natal exposures and breast tissue composition.

Methods

A sample of 500 young, nulliparous women (aged approximately 21 years) from a U.K. pre-birth cohort underwent a magnetic resonance imaging examination of their breasts to estimate percent water, a measure of the relative amount of fibroglandular tissue equivalent to mammographic percent density. Information on pre-natal exposures was collected throughout the mothers’ pregnancy and shortly after delivery. Regression models were used to investigate associations between percent water and pre-natal exposures. Mediation analysis, and a systematic review and meta-analysis of the published literature, were also conducted.

Results

Adjusted percent water in young women was positively associated with maternal height (p for linear trend [p t] = 0.005), maternal mammographic density in middle age (p t = 0.018) and the participant’s birth size (p t < 0.001 for birthweight). A 1-SD increment in weight (473 g), length (2.3 cm), head circumference (1.2 cm) and Ponderal Index (4.1 g/cm3) at birth were associated with 3 % (95 % CI 2–5 %), 2 % (95 % CI 0–3 %), 3 % (95 % CI 1–4 %) and 1 % (95 % CI 0–3 %), respectively, increases in mean adjusted percent water. The effect of maternal height on the participants’ percent water was partly mediated through birth size, but there was little evidence that the effect of birthweight was primarily mediated via adult body size. The meta-analysis supported the study findings, with breast density being positively associated with birth size.

Conclusions

These findings provide strong evidence of pre-natal influences on breast tissue composition. The positive association between birth size and relative amount of fibroglandular tissue indicates that breast density and breast cancer risk may share a common pre-natal origin.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13058-016-0751-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: ALSPAC, Birthweight, Breast density, In utero, Magnetic resonance imaging, Mammographic density, Maternal, Mediation analysis, Pre-natal, Systematic review

Background

Recent meta-analyses and pooled analyses [1, 2] have identified positive associations between birth size and breast cancer risk, suggesting that the pre-natal period may be a critical time window of exposure for risk of breast cancer later in life. The mechanisms linking birth size to risk are not known, but birth size may be a correlate of in utero exposures to mitogens [1]. Such mitogens may influence the size of the stem cell pool in the embryonic breast, which, in turn, affects the development of the gland at puberty and, ultimately, breast cancer risk later in life [3]. If true, such a hypothesis would suggest that the association between pre-natal exposures and breast cancer risk may be mediated, at least in part, by influences on breast tissue composition in early adulthood.

Mammographic percent density, which reflects variations in the relative amounts of fat and fibroglandular tissue in the breast given a woman’s age and body mass index (BMI), is a strong breast cancer risk factor [4]. Mammographic percent density is highest at young ages, when susceptibility to breast carcinogens is greatest, and tracks through a woman’s adult life [5]. Despite evidence that mammographic percent density may be established early in life, few studies have assessed the association of birth size and other pre-natal exposures with mammographic percent density. Existing studies have been restricted to middle-aged and older women, as the risk of radiation-induced breast cancer precludes the use of mammography at younger ages [6]. Consequently, there has been no investigation of the role of pre-natal exposures in young women (i.e., prior to the breast tissue being affected by reproductive-related events).

In the present study, we investigated the relationship between prospectively collected data on a wide range of pre-natal exposures, including birth size, and breast tissue composition, as assessed by ionising radiation-free magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), in nulliparous young women within a British pre-birth cohort, and we conducted a systematic review of the relevant published literature.

Methods

Study population

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) is a prospective pre-birth cohort of 14,775 children born in Avon, England (representing 72 % of the eligible population [7]), between 1 April 1991 and 31 December 1992 [7, 8]. For this study, young, nulliparous women born from singleton pregnancies who regularly participated in follow-up surveys and had never been diagnosed with cancer or a hormone-related disease were invited to attend an MRI examination of their breasts at the University of Bristol Clinical Research and Imaging Centre between June 2011 and November 2014. Women who had contraindications for MRI (e.g., pregnancy, metal implants) were excluded. Of the 2530 potentially eligible women invited, 500 (19.8 %) attended. The low response rate reflected the highly demanding nature of the study, as well as relocation away from the study area (e.g., to attend university). However, participants were similar to potentially eligible women who did not participate in relation to socio-demographic factors and body size measurements (e.g., mean birthweight and BMI at age 16 years were 3390.9 g [SD 21.6 g] and 21.2 kg/m2 [SD 0.2 kg/m2], respectively, amongst women who participated, and 3397.4 g [SD 11.4 g] and 21.5 kg/m2 [SD 0.1 kg/m2], respectively, amongst those who did not). Mothers of participants provided access to their mammograms taken as part of the U.K. national screening programme if they were in the targeted age group (50–70 years).

The study received approval from all relevant ethics committees (listed below in the Ethics approval and consent to participate subsection). Participants provided written informed consent.

Data collection

Information on maternal, in utero and birth size variables was collected from self-administered maternal questionnaires at enrolment in early gestation, throughout pregnancy and shortly after delivery, supplemented by obstetric and paediatric records [9]. During their MRI examinations, participants completed a short questionnaire on menstruation-related variables, and anthropometric measurements were taken. The mother’s BMI, parity and menopausal status closest to the time of mammography were obtained through face-to-face clinical assessments and self-completed questionnaires. The study website contains details of all the data that are available through a fully searchable data dictionary [9].

Breast tissue composition assessment

Young women underwent an examination using a 3-T Siemens MAGNETOM Skyra MRI system (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a breast coil that surrounded both breasts and with the women in prone position. For each woman, three sets of images through both breasts were obtained: (1) T1-weighted VIBE 3-D images (approximately 176 images per woman) with a voxel size of 0.76 × 0.76 × 0.90 mm3, (2) T2-weighted transaxial images (approximately 40 images per woman) with in-plane resolution of 0.85 × 0.85 mm2 and slice thickness of 4 mm, and (3) sagittal Dixon images (between 37 and 44 per woman) with in-plane resolution 0.74 × 0.74 mm2 and slice thickness of 7.7 mm. Fully automated algorithms were developed to estimate breast volume using both T1-weighted and T2-weighted images and perform fat/water segmentation on T2-weighted images, whilst semi-automated breast and fat/water segmentation methods were developed for the Dixon images (details provided in Additional file 1: Methods 1). These algorithms yielded left-right average estimates of volumes (in cubic centimetres) of breast, water and fat (the latter two correspond to mammographic dense and non-dense tissues, respectively), as well as percent water. Percent water has been shown to be highly correlated with mammographic percent density of the same women [10–12]. In comparisons in a random sample of 200 participants, we found little difference in breast measurements across the different MRI images (Additional file 1: Methods 1), and results from T1-weighted and T2-weighted images are presented here. Valid breast parameters were obtained for 491 of the 500 participants who underwent the MRI examination.

Processed digital mammographic images were successfully retrieved from screening centres for 175 mothers. Left and right craniocaudal images were read using the Cumulus semi-automated area-based method [13, 14] to estimate average breast, non-dense and dense areas (in square centimetres), and percent density (mammographic percent density). Cumulus density readings of processed images are strong predictors of breast cancer risk [15]. Readings were performed by a single observer (IdSS) who was blind to the women’s characteristics (within-observer intra-class correlation 0.92).

Statistical analysis

Linear regression models were fitted to examine associations between participants’ breast tissue parameters and maternal, in utero and birth size variables. Breast tissue parameters were first log-transformed to achieve near-normal distributions. To improve interpretability, exponentiated estimated regression parameters are reported; these represent the relative percent change (RC) in breast measurements associated with a unit increase in the exposure of interest. Continuous exposure measurements were standardised and, where appropriate, grouped into relevant categories or using quartiles as cut-off points. Exposure effects were adjusted for (1) age, BMI, phase of menstrual cycle (luteal, follicular and irregular period), hormonal contraceptive use at the time of MRI (as described in Table 1), and, when investigating the role of maternal mammographic density measurements, also for maternal age and BMI at mammography; and (2) further adjusted for other maternal, in utero or birth size variables as specified in the tables and figures. For simplicity, variables (1) and (2) will be referred to hereafter as minimally and mutually adjusted effects, respectively.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of the participants and their mothers

| n | Mean % | SD | Median | IQR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics at MRI examination | |||||

| Age, months | 491 | 257.9 | 11.0 | 259.0 | 14.0 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 487 | 23.9 | 4.4 | 23.0 | 5.1 |

| Menstrual cyclea | |||||

| Luteal phase | 70 | 14.4 | |||

| Irregular periods | 50 | 10.3 | |||

| Follicular phase | 28 | 5.8 | |||

| Use of hormonal contraception | 339 | 69.6 | |||

| Left-right average breast volume, cm3 | 490 | 647.2 | 461.1 | 507.8 | 469.2 |

| Left-right average breast fat volume, cm3 | 490 | 406.3 | 349.5 | 292.2 | 327.9 |

| Left-right average breast water volume, cm3 | 490 | 240.9 | 131.2 | 209.8 | 172.4 |

| Left-right average breast percent water,b % | 491 | 41.8 | 10.3 | 41.7 | 16.0 |

| Maternal characteristics at participant’s birth | |||||

| Mother’s age at menarche, years | 449 | 12.9 | 1.5 | 13.0 | 2.0 |

| Mother ever used oral contraceptive pill, % | 452 | 96.7 | |||

| Age when mother first used contraceptive pill, years | 435 | 18.8 | 3.1 | 18.0 | 3.0 |

| Mother’s height, cm | 446 | 16.6 | 6.5 | 165.1 | 7.6 |

| Mother’s age at first birth, years | 463 | 26.5 | 4.7 | 27.0 | 7.0 |

| Mother’s age at participant’s birth, years | 467 | 29.9 | 4.5 | 30.0 | 6.0 |

| Mother’s parity at participant’s birth | |||||

| 0 | 223 | 48.5 | |||

| 1 | 161 | 35.0 | |||

| 2+ | 76 | 16.5 | |||

| Mother’s pre-pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 430 | 22.3 | 3.0 | 21.7 | 3.5 |

| Maternal history of BC when participant was 8 years old, % | 355 | 11.6 | |||

| Maternal characteristics at mammography | |||||

| Age, years | 176 | 52.7 | 3.9 | 52.0 | 5.0 |

| BMI,c kg/m2 | 165 | 24.3 | 4.7 | 23.3 | 5.4 |

| Left-right average breast area, cm2 | 176 | 295.0 | 141.3 | 266.8 | 167.1 |

| Left-right average dense area, cm2 | 176 | 63.9 | 37.3 | 59.3 | 37.6 |

| Left-right average percent density, % | 176 | 25.3 | 13.4 | 24.8 | 20.4 |

| In utero exposures | |||||

| Placental weight, g | 121 | 587.1 | 132.9 | 580.0 | 160.0 |

| Absolute GWG, week 0 to delivery, kg | 422 | 12.1 | 3.9 | 12.0 | 5.0 |

| Mother drank alcohol during pregnancy, % | 459 | 74.1 | |||

| Mother smoked during pregnancy, % | 464 | 10.6 | |||

| Participant characteristics at birth | |||||

| Birthweight, g | 460 | 3395.0 | 472.6 | 3400.0 | 565.0 |

| Birth length, cm | 362 | 50.5 | 2.3 | 50.8 | 2.7 |

| Head circumference, cm | 370 | 34.6 | 1.2 | 34.6 | 1.5 |

| PI,d g/cm3 | 358 | 26.4 | 4.1 | 26.1 | 3.2 |

| Gestational age,e weeks | |||||

| < 39 | 93 | 19.9 | |||

| 39 | 101 | 21.6 | |||

| 40 | 132 | 28.3 | |||

| ≥ 41 | 141 | 30.2 | |||

Abbreviations: MRI Magnetic resonance imaging, BC Breast cancer, BMI Body mass index, GWG Gestational weight gain, PI Ponderal Index

aEstimated for women not using hormonal contraception by calculating the number of days since the last menstrual period (date of MRI to start of last menstrual period). Luteal (days 14–17 to 28–31) and follicular (days 0 to 14–17) phases and an ‘irregular period’ (32+ days) were defined using average length of menstrual cycle

bSections of the breast were missing in the MRI images for one participant; thus, volumetric measurements could not be ascertained, and percent water only was used

cClinically measured or self-reported BMI. Median time interval between BMI assessment and mammography was 3 years (IQR 1.5 years)

dPI defined as birthweight (g)/birth length (cm3)

eData available only as a categorical variable

Mediation analyses were performed to investigate separately whether the effect of maternal exposures on the participants’ percent water were mediated via birth size, and whether the effect of birth size was mediated through adult height and BMI [16]. Linear regression models were fitted to the percent water, the exposure and each mediator in turn, with relevant confounders included and interactions between each exposure-mediator pair investigated. Results are presented in terms of direct (i.e., not mediated) and indirect (i.e., mediated) effects and expressed as percent changes, with 95 % CIs for the indirect effects obtained by bootstrapping [17].

Sensitivity analyses were conducted using (1) an alternative method to estimate percent water on Dixon images (Additional file 1: Methods 1) and (2) multiple imputation to deal with missing exposure and confounder data under the missing-at-random assumption [18] to obtain results based on all participants with valid MRI breast parameters (n = 491). Imputation by chained equations method was used, including all the exposures, confounding factors and outcomes involved in the analysis. The models described above were fitted to each of 20 imputed datasets, and overall estimates were obtained using Rubin’s rules [19].

Data analysis was conducted using STATA version 14 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). All tests of significance were two-sided.

Systematic review of pre-natal exposures and breast tissue composition

The original protocol and methodology of the review are given in Additional file 1: Methods 2 and 3. Briefly, a search for studies published between 1 January 1970 and 25 September 2015 was conducted in PubMed using the search terms detailed in Additional file 1: Methods 3. Paper screening and data extraction were completed independently by two reviewers (RD, IdSS). The quality of the eligible papers was assessed by developing a standardised quality score (ranging from 0 [lowest quality] to 59 [highest quality]) based on 15 individual parameters reflecting the potential for selection bias, measurement error and confounding (Additional file 1: Methods 3).

Estimates of association between pre-natal exposures and breast density, as ascertained by mammography or an alternative approach, were extracted from each study and reported graphically using forest plots, whenever appropriate. To summarise the results in terms of linear trends, we first estimated linear effects across categorical exposures using study-specific weighted regression across the reported regression coefficients (with weights proportional to their SE). Derived study-specific linear trend coefficients and study-specific linear effects of continuous exposures were then summarised using random effects meta-analysis. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using the I 2 statistic. To examine potential sources of heterogeneity, study-specific trend coefficient estimates were stratified according to variables defined a priori (i.e., menopausal status at mammography, source of pre-natal exposure data, breast density assessment method). Funnel plots and Egger’s test were used to assess publication bias.

Results

Study subjects

Table 1 presents the distributions of maternal, in utero and birth size characteristics of the participants. The mean age of the participants at the time of MRI was 21.5 years. Relative to mothers for whom mammograms were not available, those with mammograms were, as expected given the age group targeted by the U.K. national breast screening programme, older (31.7 vs. 28.8 years) and more likely to have older children (55.6 % vs. 49.3 %) at the participants’ birth. There were no differences, however, in the participants’ characteristics according to whether a mammogram could be retrieved for their mothers (data not shown). Participants’ percent water was inversely associated with BMI at the time of MRI, but not with age (reflecting their rather narrow age range) or menstrual phase/contraceptive use (Additional file 2: Table S1). Mothers’ mammographic percent density was inversely associated with both their age and their BMI at the time of mammography, but not with parity or menopausal status (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Pre-natal exposures and MRI breast tissue measurements

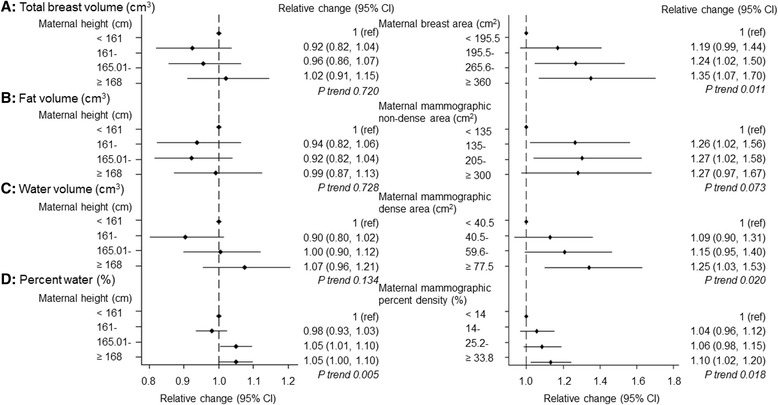

In univariate analyses, percent water in daughters was positively correlated with maternal mammographic percent density (r = 0.23; p = 0.003; n = 175), mirroring positive daughter-mother correlations in the amounts of dense tissue (r = 0.18; p = 0.014) (Additional file 3: Figure S1). Both maternal height and mammographic percent density were positively associated with the participants’ percent water in minimally (Fig. 1d) and mutually (Table 2) adjusted analyses. One SD increment in maternal height and mammographic percent density were associated, respectively, with a 2 % (RC 1.02; 95 % CI 1.00–1.04) and a 6 % (RC 1.06; 95 % CI 1.01–1.10) increase in percent water (Table 2), reflecting mainly increases in water volume (Fig. 1c). No associations with other maternal characteristics or in utero exposures were observed (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based breast tissue measurements in relation to maternal height and maternal mammographic breast measurements (minimally adjusted estimates). ref Reference category. MRI breast measurements were log-transformed, and exponentiated estimated regression parameters, with 95 % CI calculated by exponentiating the original 95 % CIs, are presented. Models were adjusted for the participant’s age, BMI and menstrual phase/hormonal contraceptive use at the time of MRI and, where appropriate, mother’s age and BMI at mammography. Continuous variables were centred at the mean

Table 2.

Mutually adjusted associations of MRI percent water in daughters with maternal characteristics and markers of in utero exposures estimated using the complete and imputed data

| Relative change in MRI percent water, geometric mean (95 % CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Complete dataa | Imputed datab | |

| Maternal characteristicsc | n = 303 | n = 490 |

| At participant’s birth only | ||

| Mother’s age at menarche (per 1 SD 1.5 years) | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) |

| Age mother first used OC (per 1 SD 3.1 years) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) |

| Mother’s height (per 1 SD 6.5 cm) | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) |

| Mother’s age at first birth (per 1 SD 4.7 years) | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) |

| Mother’s age at participant’s birth (per 1 SD 4.5 years) | 1.00 (0.96–1.03) | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) |

| Mother’s pre-pregnancy BMI (per 1 SD 3.0 kg/m2) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) |

| Mother’s parity at participant’s birth | ||

| 0 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 1 | 1.04 (0.99–1.10) | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) |

| 2+ | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) |

| Mother had a history of breast cancer | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) |

| Maternal characteristics at participant’s birth and at mammographyd | ||

| Mother’s MPD (per 1 SD 13.4 %) | 1.06 (1.01–1.10) | – |

| In utero exposurese | n = 107 | n = 490 |

| Placental weight (per 1 SD 133.5 g) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) |

| Absolute GWG, week 0 to delivery (per 1 SD 3.9 kg) | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) |

| Mother drank alcohol during pregnancy (%) | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 1.01 (0.91–1.11) | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) |

| Mother smoked during pregnancy (%) | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 0.95 (0.89–1.03) | 0.99 (0.96–1.04) |

Abbreviations: MRI Magnetic resonance imaging, BMI Body mass index, GWG Gestational weight gain, OC Oral contraceptives, MPD Mammographic percent density ref Reference category

MRI breast measurements were log-transformed, and exponentiated estimated regression parameters, with 95 % CIs calculated by exponentiating the original 95 % CIs, are presented. Bold indicates 95 % CI do not cross the null (1.00)

aAnalysis restricted to those with non-missing data for all variables included in the models

bSee Statistical methods section in main text

cMaternal and confounding factors (age, BMI and menstrual phase/hormonal contraceptive use at MRI) were included in the model simultaneously

dAnalysis restricted to the subset of participants for whose mothers it was possible to retrieve a mammogram (n = 116). Model includes all the maternal characteristics at the participant’s birth listed in the table as well as maternal MPD in later life (mean age at mammography 52.8 years; Table 1), adjusting for the daughters’ age, BMI and menstrual phase at the time of MRI and for the mothers’ age and BMI at the time of mammography

eIn utero and confounding factors (age, BMI and menstrual phase/hormonal contraceptive use at the time of MRI) were included in the model simultaneously

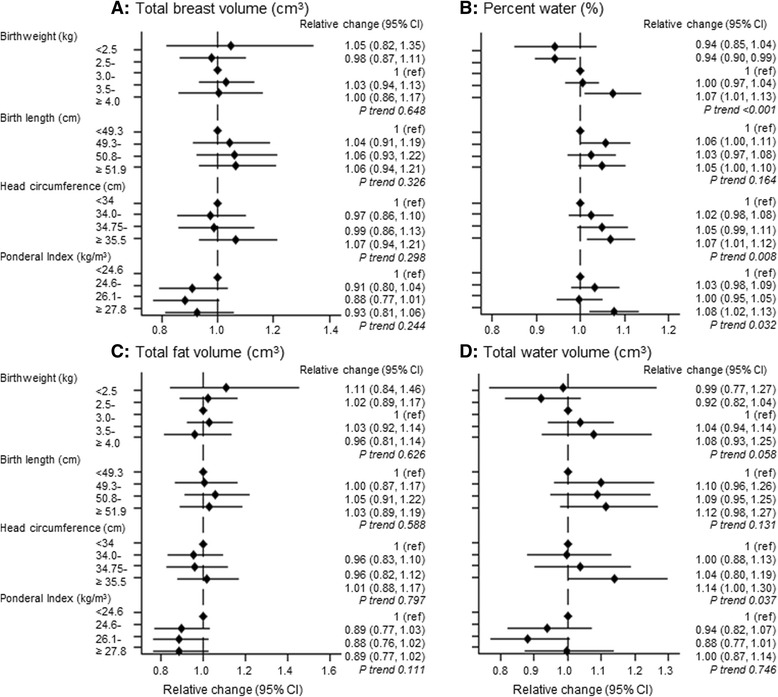

Weight, length, head circumference and ponderal index at birth were all associated with percent water in minimally adjusted analysis (Fig. 2b), reflecting similar positive associations with water volume, with the exception on ponderal index, (Fig. 2d). A 1-SD increment in weight (473 g), length (2.3 cm), head circumference (1.2 cm) and ponderal index (4.1 g/cm3) at birth was associated with a minimally adjusted RCs of 1.03 (95 % CI 1.02–1.05), 1.02 (1.00–1.03), 1.02 (1.01–1.04) and 1.01 (1.00–1.03), respectively. For birthweight, this corresponded to an absolute 5.45 % (95 % CI 1.05–9.85) difference in minimally adjusted mean percent water between the extreme categories of the birthweight distribution (i.e., ≥4.0 vs. <2.5 kg) (Additional file 3: Figure S2). Gestational age was not associated with percent water (Additional file 2: Table S2); indeed, further adjustment for this variable did not materially affect the magnitude of the birth size-percent water association (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) breast tissue measurements in relation to the participant’s size at birth (minimally adjusted estimates). ref Reference category. MRI breast measurements were log-transformed, and exponentiated estimated regression parameters, with 95 % CIs calculated by exponentiating the original 95 % CIs, are presented. Models are adjusted for the participant’s age, body mass index (BMI) and menstrual phase/hormonal contraceptive use at the time of MRI and, where appropriate, mother’s age and BMI at the time of mammography. Continuous variables were centred at the mean

Table 3.

Associations between participant’s size at birth and MRI percent water

| Relative change in MRI percent water, geometric meansa (95 % CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete datab | Imputed datac (n = 491) | |||

| Absolute size vs. rate of growth | n = 455 | |||

| Model 1 | Birthweight (per 1 SD 472.6 g) | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | |

| Model 2 | Birthweight (per 1 SD 472.6 g) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | <39 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| 39 | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | ||

| 40 | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | ||

| 41+ | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) | ||

| LR test/Wald test p valued | 0.519 | 0.477 | ||

| Which measure best captures linear (skeletal) growth? | n = 356 | |||

| Birth length (per 1 SD 2.3 cm) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | ||

| Head circumference (per 1 SD 1.2 cm) | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | ||

| Linear growth vs. adiposity | n = 361 | |||

| Model 1 | Birthweight (per 1 SD 472.6 g) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 1.03 (1.02-1.05) | |

| Model 2 | Birthweight (per 1 SD 472.6 g) | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | |

| Head circumference (per 1 SD 1.2 cm) | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | ||

| LR test/Wald test p valued (n = 353) | 0.671 | 0.917 | ||

| Model 1 | Birthweight (per 1 SD 472.6 g) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | |

| Model 2 | Birthweight (per 1 SD 472.6 g) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | |

| Ponderal Index (per 1 SD 4.1 g/cm3) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | ||

| LR test/Wald test p valued | 0.577 | 0.654 | ||

Abbreviations: MRI Magnetic resonance imaging, LR Likelihood ratio test, ref Reference category

aMRI percent water was log-transformed for the analysis, and exponentiated estimated regression parameters, with 95 % CIs calculated by exponentiating the original 95 % CIs, are presented. Models adjusted for age, BMI z-score and menstrual phase/hormonal contraceptive use at the time of MRI scan. Bold indicates 95 % CI do not cross the null (1.00)

bAnalysis restricted to those with non-missing data for all variables included in each model

cSee Statistical methods section of main text

dLR test performed on the complete record data, while a Wald test was performed on the imputed data (and summarised using Rubin’s rule), to test the null hypothesis that the inclusion of the additional variable in model 2 did not improve the fit to the data

Weight and length at birth were correlated with each other (r = 0.67, p < 0.0001), and both were correlated with head circumference (r = 0.71, p < 0.0001, and r = 0.50, p < 0.0001, respectively) and ponderal index (r = 0.29, p = 0.001, and r = 0.46, p = 0.001, respectively). Both length and head circumference reflect linear (skeletal) growth, but in mutually adjusted analysis only the association of the latter with percent water persisted (Table 3). Ponderal index reflects adiposity, while birthweight is a function of both linear growth and adiposity; however, only the birthweight-percent water association persisted when head circumference or ponderal index was included in the model (Table 3).

Sensitivity analyses

Similar findings were observed in multiple imputation analyses or when the breast tissue measurements were estimated using an alternative method to measure percent water on Dixon images (Tables 2 and 3 and Additional file 2: Table S2).

Mediation analyses

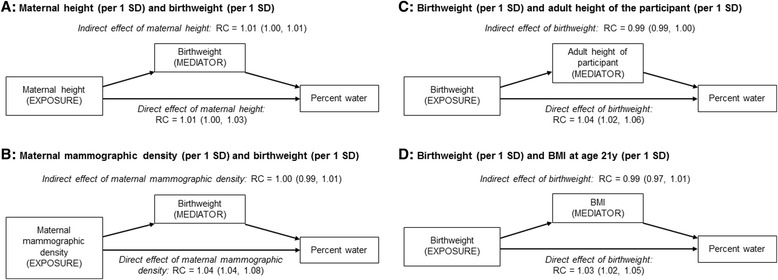

The association between maternal height and the participants’ percent water was partly mediated by birthweight, with about half of its total effect (mutually adjusted total effect RC = 1.01; 95 % CI 1.00–1.01) being attributable to its influence on birthweight and the effect of birthweight on percent water (indirect effect 1.01; 95 % CI 1.00–1.01) (Fig. 3a). For the birthweight-percent water association (mutually adjusted total effect 1.03; 95 % CI 1.02–1.05), there appears to be some evidence of protective mediation through the adult height of the participants (indirect effect RC = 0.99; 95 % CI 0.99–1.00). In contrast, there was no evidence of mediation of the effect of maternal mammographic percent density on the participants’ percent water through birthweight, nor was there evidence of the effect of birthweight on percent water via BMI at the time of MRI (Fig. 3b and d).

Fig. 3.

Indirect and direct effects (relative change in geometric mean) of a) maternal height and b) maternal mammographic density accounting for the mediating effect of birthweight, and birth weight accounting for the mediating effect of c) height and d) BMI at age 21 years, on MRI percent water. RC Relative percent change, BMI Body mass index. MRI-based percent water was log-transformed for the analysis, and exponentiated estimated regression parameters, with 95 % CIs calculated by exponentiating the original 95 % CIs, are presented. Model shown in (a) was adjusted for age, BMI and menstrual phase//hormonal contraceptive use at the time MRI, maternal education level, pre-pregnancy BMI, and smoking during pregnancy. Model shown in (b) was adjusted as for (a) plus maternal height, and maternal age and BMI at the time of mammography. Model shown in (c) was adjusted for age, BMI and menstrual phase/hormonal contraceptive use at the time of MRI, maternal education level, height, and smoking during pregnancy. Model shown in (d) was adjusted for age, BMI (linear and quadratic term), and menstrual phase/hormonal contraceptive use at the time of MRI

Systematic review

In the systematic search, we identified 208 abstracts, of which 12 were eligible (Additional file 3: Figure S3). Of these, most were conducted with post-menopausal women, although four included or were restricted to pre-menopausal participants [20–23]. Two studies included women in young adulthood [12, 24], but these contributed data only to the mothers-daughters breast density analysis (Additional file 2: Table S3 and S4). These two studies [12, 24] were also the only ones not to use mammography to assess participants’ breast density. All but two studies adjusted for age, BMI and, if appropriate, also menopausal status at breast density assessment [21, 25].

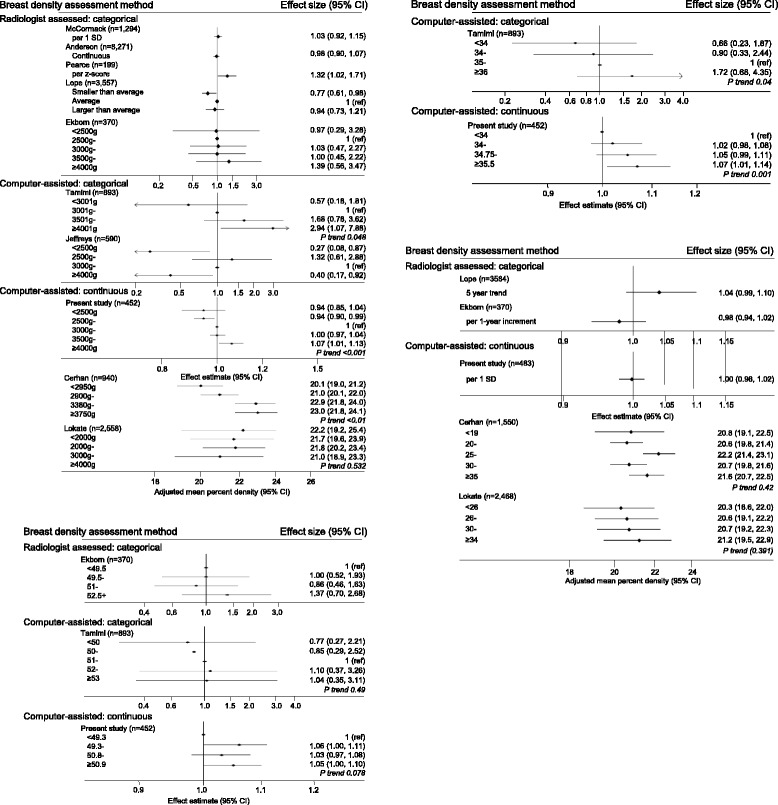

Nine studies investigated associations between birth size measurements and adult breast density. The meta-analysis of their study-specific trend estimates, including those derived from the present study, revealed positive trends in the relative amount of fibroglandular tissue in the breast, as assessed by mammographic percent density or percent water, with birth size, albeit with high between-study heterogeneity (Fig. 4a and Table 4). Analysis by potential source of heterogeneity showed that this positive trend was stronger among studies assigned a high overall quality score, and in particular among those that relied on less error-prone birth size data from hospital records and more objective computer-assisted density measurements (Table 4). The positive trend in percent breast density with birth size was found in analyses restricted to study-specific estimates derived from pre- or post-menopausal women only, albeit more marked for the latter (Table 4). Similar results were observed when estimates derived from the present study were excluded. There was evidence of publication bias (p<0.001), which disappeared (p = 0.928) when the Tamimi study [26] was excluded (Additional file 3: Figure S4).

Fig. 4.

Systematic review of studies investigating (a) birth size measurements and (b) maternal age and percent breast density. I. Birthweight and percent density, II. birth length and percent density, and III. head circumference and percent density data are shown. Studies classified as using a computer-assisted categorical breast density assessment method collected a quantitative measure of mammographic percent density but used a categorical measure in the analysis

Table 4.

Meta-analysis of the association between various birth size measurements and percent breast density, stratified by potential sources of between-study heterogeneity

| Perinatal factor | Number of studiesa | Average relative changeb (95 % CI) | z-score p value | I 2 statistic (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth size measurements: | |||||

| Birthweight | |||||

| Overallc | 9 | 1.59 (1.58–1.59) | <0.001 | 100.0 | [21, 22, 25, 26, 33, 35, 49, 50]; present study |

| Using Andersen et al. [35] OR2d | 9 | 1.59 (1.58–1.59) | <0.001 | 100.0 | |

| Excluding present study | 8 | 1.63 (1.62–1.63) | <0.001 | 100.0 | |

| Menopausal status | |||||

| Pre-menopausal women | 3 | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <0.001 | 38.1 | [21, 22]; present study |

| Post-menopausal women | 3 | 1.72 (1.71–1.72) | <0.001 | 99.7 | [21, 22, 26] |

| Source of birthweight data | |||||

| Self-/parent report | 4 | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.117 | 91.0 | [21, 22, 35, 50] |

| Hospital records | 5 | 1.67 (1.66–1.67) | <0.001 | 10.0 | [25, 26, 33, 49] present study |

| Breast density assessment method | |||||

| Radiographer-assessed | 4 | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | 0.066 | 49.7 | [25, 33, 35, 49] |

| Computer-assisted | 5 | 1.59 (1.58–1.59) | <0.001 | 100.0 | [21, 22, 26, 50] present study |

| Restricted to hospital records | |||||

| Radiographer-assessed | 3 | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) | 0.013 | 33.3 | [25, 33, 49] |

| Computer-assisted | 2 | 1.67 (1.66–1.67) | <0.001 | 100.0 | [26]; present study |

| Quality scoree | |||||

| Highest tertile (≥50) | 3 | 1.67 (1.66–1.67) | <0.001 | 100.0 | [26, 35]; present study |

| Middle tertile (40–50) | 3 | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.142 | 94.7 | [22, 48, 50] |

| Lowest tertile (<40) | 3 | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 0.160 | 26.3 | [21, 25, 35] |

| Birth length | |||||

| Overall | 3 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.051 | 89.2 | [25, 26]; present study |

| Head circumference | |||||

| Overall | 2 | 1.11 (1.11–1.11) | <0.001 | 100.0 | [26]; present study |

| Maternal age | |||||

| Overall | 5 | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | <0.001 | 31.7 | [20, 22, 25, 50]; present study |

| Excluding present study | 4 | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | <0.001 | 21.9 | |

| Menopausal status | |||||

| Pre-menopausal women | 3 | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.539 | 0.0 | [20, 22]; present study |

| Post-menopausal women | 3 | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | <0.001 | 0.0 | [20, 22, 50] |

| Quality score (maximum 59)d | |||||

| Highest (≥40) | 3 | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | <0.001 | 17.4 | [22, 50]; present study |

| Lowest (<40) | 2 | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 0.898 | 67.2 | [20, 25] |

aLope et al. [20] was not included in the birthweight meta-analysis, owing to concerns about the validity of a summary trend measure across the limited number of categories (three groups)

bDue to the high between-study heterogeneity in most strata, these average estimates should be interpreted simply as indicators of the direction of the trend in breast density with increasing birth size

cMeta-analysis uses OR1 from Andersen et al. [35] as reported in Table S3, which is adjusted for age at screening and birth cohort: OR 0.98; 95 % CI 0.90–1.07

dMeta-analysis uses OR2 from Andersen et al. [35] as reported in Table S3, which is adjusted for age at screening, birth cohort and BMI at age 13 years: OR 1.11; 95 % CI 1.02–1.22

eRange 0–59; see Methods section of main text and Additional file 1: Methods 3 for description of how study quality scores were developed

Seven studies reported on associations between other pre-natal exposures with adult breast density (Additional file 2: Table S4). Meta-analyses of study-specific estimates derived from five studies, including the present one, revealed a positive trend between maternal age and relative amount of fibroglandular tissue in the breast, which was stronger in analyses restricted to post-menopausal women, with relatively low between study-heterogeneity (Fig. 4b and Table 4). There was some indication of publication bias (p = 0.032) (Additional file 3: Figure S4). Meta-analyses were not possible for other pre-natal exposures, owing to the small number of studies and differences in the way these variables were measured or analysed (Additional file 2: Table S4), but qualitative assessment of the evidence did not reveal any consistent associations of percent breast density with maternal parity (based on n = 4 studies, including the present one), maternal smoking (n = 3) or alcohol intake (n = 2) during pregnancy, gestational age (n = 5), or placental weight (n = 2).

Discussion

In this unique pre-pregnancy cohort with a wide range of maternal, in utero and birth size measurements, we found evidence of a positive association between birth size and percent breast density, as measured by percent water, in young adult women, which was not mediated by current body size. Birth size has been shown to be positively associated with breast cancer risk in later life in pooled analysis and meta-analysis [1], albeit not in a recent cohort based on self-reported birthweight [27]. Overall, our findings are consistent with the birth size-breast cancer association being explained by foetal growth influences on breast tissue composition. Maternal height and maternal mammographic percent density were also positively correlated with the participants’ percent water, albeit with evidence that the maternal height association was partly mediated through the effect of birth size on percent water.

The magnitude of the birth size association with percent breast density is small but not negligible. A 1 % increase in percent density corresponds to a 2 % increase in breast cancer risk [28]. Assuming that the effect of birthweight is entirely mediated through changes in breast tissue composition, the observed 3 % increase in percent breast density associated with a 1-SD increment in birthweight would translate to a 6 % increase in breast cancer risk, consistent with the 6 % (95 % CI 2–9 %) increase in breast cancer risk associated with a 0.5-kg increase in birthweight reported in a pooled analysis of original individual-level data derived from 32 studies [29]. Such an effect on risk would be similar to effects reported for other established breast cancer risk factors (e.g., 5-cm increase in adult height [30, 31] or 10-g daily alcohol consumption [31]).

Strengths and limitations of the present study

Strengths of the present study include the unique pre-birth cohort design with a wide range of prospectively collected pre-natal exposure data. Breast tissue measurements were collected from ionising radiation-free MRI examinations, making this the first study to examine the effect of pre-natal influences on breast tissue composition in young adulthood, prior to changes induced by pregnancies and breastfeeding. Objective (fully automated and, hence, observer-independent) volumetric breast tissue composition measurements were taken using a previously developed and evaluated approach [32].

The response rate was low (approximately 20 %), although comparable to a similar MRI breast study [12], but there was no evidence that the participants constituted a biased sample. Data were missing for some variables, but analyses of complete records and imputed datasets produced similar findings.

Consistency with other studies

Meta-analysis of study-specific estimates derived from all eligible studies identified in the systematic review, together with those derived from the present study, revealed a significant positive trend between birth size and percent breast density, as assessed by mammographic percent density or percent water, albeit with marked between-study heterogeneity. Positive associations between birthweight and percent breast density were reported in studies based on computer-assisted methods to assess breast density [22, 26], but not in those that relied on radiologist-assessed categorical measurements (e.g., Wolfe’s [33] or Boyd’s [34] categories, American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) [35]). Inconsistencies are likely due to the relatively small effect of birth size, which cannot be captured by categorical density classifications (Additional file 3: Figure S2). Analyses stratified by source-of-exposure data showed a significant positive trend between hospital-recorded birthweight measurements and percent breast density, but not in studies that used parental or adult self-reports, consistent with findings derived from a pooled analysis of birth size and breast cancer studies [1].

Plausibility of the findings

Birth size is a strong predictor of later physical development, with both weight and length at birth being associated with childhood growth, age at menarche [36] and adult body size [37]. Thus, the observed association between birth size and percent breast density may be mediated by childhood and adolescent growth trajectories [26]. Mutually adjusted analysis revealed that birthweight had the strongest independent association with percent water, suggesting that both linear growth and adiposity may affect breast tissue composition later in life. Furthermore, the association of birthweight with percent water did not appear to be mediated primarily via BMI at the time of MRI examination, suggesting that the effect is mainly independent of childhood and adolescent growth. There was some indication of a protective mediation effect of adult height in the association of birthweight with percent water, which may potentially reflect interactions between birth size, post-natal catch-up growth and pubertal development on percent water. Overall, dependent on the strong assumption of no unmeasured confounding, the mediation analysis provides strong evidence of a causal association between birthweight and breast tissue composition.

The observed associations with birth size and percent water mostly reflect associations with water volume, indicating that the amount of fibroglandular tissue in the breast may be set in utero. These findings parallel the effect of birth size on breast cancer risk and provide further support for the hypothesis that the intrauterine environment may play a role in determining both breast tissue composition and breast cancer risk [38, 39]. The pool of breast-specific stem cells, whose size is determined in utero [40], may be a critical factor linking pre-natal exposures to breast tissue composition and breast cancer risk in later life. In utero levels of growth factors (e.g., insulin-like growth factors) and hormones (e.g., sex hormones) are thought to act as mitogens, influencing both the pool size of breast-specific stem cells and possibly birthweight [41], with the former likely to be strongly correlated with the amount of fibroglandular tissue present in the fully developed breast [42].

Maternal height and mammographic density were also positively related to percent water, supporting previous evidence that percent breast density is a highly heritable trait. Twin studies have estimated that an additive genetic model explains 53–60 % of the variance in percent breast density [43, 44]. In the present study, the observed correlation between the participants’ percent water and their mothers’ mammographic percent density was r = 0.23 (Additional file 3: Figure S1), consistent with previous studies of mothers and daughters (r = 0.25) [12] and dizygotic twin pairs (r = 0.27) [45]. Maternal adult height is strongly correlated with daughters’ adult height (in this study, r = 0.49), and greater adult height is associated with a higher amount of fibroglandular tissue in the breast [46, 47]. Furthermore, adult height is positively associated with breast cancer risk, and genetic variants and biological pathways affecting adult height play an important role in the aetiology of breast cancer [30]. Maternal height modifies the effect of pregnancy hormones on birthweight [48], and thus it may also affect the risk of breast cancer in daughters through this mechanism.

Conclusions

Our study, together with the systematic review, provides the strongest evidence so far that pre-natal factors influence breast tissue composition in young adulthood, with the birth size associations with percent breast density paralleling previously reported positive birth size associations with breast cancer risk. Breast density is known to track from middle adulthood [5], but our findings indicate that high-risk women may be identified at an earlier age—a key aspect to consider for prevention [48, 49].

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting the families, and the whole ALSPAC team, the University of Bristol Clinical Research and Imaging Centre and our study nurses, Elizabeth Folkes and Sally Pearce, for recruiting and conducting the MRI examinations. We also acknowledge Maria Schmidt, who assisted us in establishing the MRI protocol.

Funding

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK project grant number C405/A12730 (to IdSS). The Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust (grant reference number 102215/2/13/2) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. Support was also provided by European Union FP7 grant VPH-PRISM (FP7-ICT-2011-9, 601040) and The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council grant Microstructures on Microwave Circuits (EP/K020439/1) (to JHH). The UCL segmentation code is part of the UCL NifTK translational medical imaging platform. Cancer Research UK and The Engineering and Physical Science Research Council provide support to the Cancer Imaging Centre at The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden Hospital in association with the Medical Research Council and Department of Health C1060/A10334, C1060/A16464 and National Health Service funding to the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the Royal Marsden. MOL is a National Institute for Health Research senior investigator.

Authors’ contributions

IdSS conceived of and designed the study and obtained the funding. JHH, SJD, MOL and DH designed the algorithms used to measure breast density using MRI. JHH designed the segmentation of T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI images. SJD designed the segmentation of Dixon MRI images. AE coordinated the initiation of the study. MCB and RD collated the data. BDS advised on the statistical analysis. RD performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. MJ provided guidance on the ALSPAC cohort. All authors made significant contributions to the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the final version.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee South West – Frenchay (REC number 11/SW/0051), the ALSPAC Law and Ethics Committee and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent.

Competing interests

DH reports having received grants from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and from the EU FP7 Programme, and during the conduct of the study he received personal fees from IHU Strasbourg and the Multidisciplinary Computational Anatomy, Japan, outside the work submitted for publication in this article. MOL reports having received grants from Cancer Research UK, has a patent on aspects of MRI image analysis used for this study (for which there is currently no activity). All other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Abbreviations

- ALSPAC

Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children

- BC

Breast cancer

- BI-RADS

American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System

- BMI

Body mass index

- GWG

Gestational weight gain

- LR

Likelihood ratio

- MPD

Mammographic percent density

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OC

Oral contraceptive

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RC

Relative percent change

Additional files

Methods 1. Validation of breast volume and fat-water segmentation methods using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images. Methods 2. Protocol of the systematic review on pre-natal exposures and breast tissue composition. Methods 3. Systematic literature review of maternal, in utero and birth size variables as well as breast tissue composition. (DOCX 1513 kb)

Mutually adjusted associations of MRI breast tissue measurements in daughters, and mammographic breast measurements in mothers, with age, anthropometry and hormone status at the time of the breast examination. Table S2. Minimally adjusted associations of MRI breast percent water in relation to maternal, in utero and birth size characteristics using complete and imputed data (n = 491), and Dixon-based MRI breast percent water. Table S3. Systematic review of studies investigating the association between birth size measurements, gestational age and percent breast density. Table S4. Systematic review of studies investigating the association between maternal and in utero exposures and percent breast density. (DOCX 103 kb)

Correlation between participants’ MRI breast tissue measurements and their mothers’ mammographic density measurements (n = 164). Figure S2. Predicted MRI breast percent water geometric means in relation to categories of maternal height, maternal mammographic percent density and participant’s size at birth (minimally adjusted estimates). Figure S3. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the systematic review. Figure S4. a and b Funnel plots for the meta-analysis of birthweight. a Number studies = 9. b Number studies = 8. (c) Funnel plot for the meta-analysis of maternal age (n = 5 studies) and percent breast density. (DOCX 497 kb)

Contributor Information

Rachel Denholm, Email: rachel.denholm@lshtm.ac.uk.

Bianca De Stavola, Email: bianca.destavola@lshtm.ac.uk.

John H. Hipwell, Email: j.hipwell@ucl.ac.uk

Simon J. Doran, Email: simon.doran@icr.ac.uk

Marta C. Busana, Email: marta.busana@lshtm.ac.uk

Amanda Eng, Email: a.j.eng@massey.ac.nz.

Mona Jeffreys, Email: mona.jeffreys@bristol.ac.uk.

Martin O. Leach, Email: martin.leach@icr.ac.uk

David Hawkes, Email: d.hawkes@ucl.ac.uk.

Isabel dos Santos Silva, Phone: +44 (0)20 7927 2113, Email: isabel.silva@lshtm.ac.uk.

References

- 1.dos Santos Silva I, De Stavola B, McCormack V, Collaborative Group on Pre-Natal Risk Factors and Subsequent Risk of Breast Cancer Birth size and breast cancer risk: re-analysis of individual participant data from 32 studies. PLoS Med. 2008;5(9):e193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michels KB, Xue F. Role of birthweight in the etiology of breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(9):2007–25. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savarese TM, Low HP, Baik I, Strohsnitter WC, Hsieh CC. Normal breast stem cells, malignant breast stem cells, and the perinatal origin of breast cancer. Stem Cell Rev. 2006;2(2):103–10. doi: 10.1007/s12015-006-0016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1159–69. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack VA, Perry NM, Vinnicombe SJ, dos Santos Silva I. Changes and tracking of mammographic density in relation to Pike’s model of breast tissue aging: a UK longitudinal study. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(2):452–61. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaffe MJ, Mainprize JG. Risk of radiation-induced breast cancer from mammographic screening. Radiology. 2011;258(1):98–105. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J, Lawlor DA, Fraser A, Henderson J, et al. Cohort profile: the ‘children of the 90s’—the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(1):111–27. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser A, Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K, Boyd A, Golding J, Davey Smith G, et al. Cohort profile: the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children: ALSPAC mothers cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(1):97–110. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Bristol, UK: Bristol University. http://www.bris.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/data-access/data-dictionary/. Accessed 7 Jan 2016.

- 10.Khazen M, Warren RM, Boggis CR, Bryant EC, Reed S, Warsi I, et al. A pilot study of compositional analysis of the breast and estimation of breast mammographic density using three-dimensional T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(9):2268–74. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson DJ, Leach MO, Kwan-Lim G, Gayther SA, Ramus SJ, Warsi I, et al. Assessing the usefulness of a novel MRI-based breast density estimation algorithm in a cohort of women at high genetic risk of breast cancer: the UK MARIBS study. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(6):R80. doi: 10.1186/bcr2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyd N, Martin L, Chavez S, Gunasekara A, Salleh A, Melnichouk O, et al. Breast-tissue composition and other risk factors for breast cancer in young women: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(6):569–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd NF, Byng JW, Jong RA, Fishell EK, Little LE, Miller AB, et al. Quantitative classification of mammographic densities and breast cancer risk: results from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(9):670–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.9.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byng JW, Boyd NF, Fishell E, Jong RA, Yaffe MJ. The quantitative analysis of mammographic densities. Phys Med Biol. 1994;39(10):1629–38. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/39/10/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vachon CM, Fowler EE, Tiffenberg G, Scott CG, Pankratz VS, Sellers TA, et al. Comparison of percent density from raw and processed full-field digital mammography data. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15(1):R1. doi: 10.1186/bcr3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Efron B, Tibshirani RT. An introduction to the bootstrap (Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability 57) London: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8(1):3–15. doi: 10.1191/096228099671525676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lope V, Pérez-Gómez B, Moreno MP, Vidal C, Salas-Trejo D, Ascunce N, et al. Childhood factors associated with mammographic density in adult women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130(3):965–74. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1664-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeffreys M, Warren R, Highnam R, Davey Smith G. Breast cancer risk factors and a novel measure of volumetric breast density: cross-sectional study. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(1):210–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerhan JR, Sellers TA, Janney CA, Pankratz VS, Brandt KR, Vachon CM. Prenatal and perinatal correlates of adult mammographic breast density. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(6):1502–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terry MB, Schaefer CA, Flom JD, Wei Y, Tehranifar P, Liao Y, et al. Prenatal smoke exposure and mammographic density in mid-life. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2011;2(6):340–52. doi: 10.1017/S2040174411000614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maskarinec G, Morimoto Y, Daida Y, Shepherd J, Novotny R. A comparison of breast density measures between mothers and adolescent daughters. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:330. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekbom A, Thurfjell E, Hsieh CC, Trichopoulos D, Adami HO. Perinatal characteristics and adult mammographic patterns. Int J Cancer. 1995;61(2):177–80. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamimi RM, Eriksson L, Lagiou P, Czene K, Ekbom A, Hsieh CC, et al. Birth weight and mammographic density among postmenopausal women in Sweden. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(4):985–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang TO, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V, Cairns BJ, Million Women Study Collaborators Birth weight and adult cancer incidence: large prospective study and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(9):1836–43. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyd NF, Lockwood GA, Byng JW, Tritchler DL, Yaffe MJ. Mammographic densities and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7(12):1133–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.dos Santos Silva I, De Stavola B, McCormack V. Birth size and breast cancer risk: re-analysis of individual participant data from 32 studies. PLoS Med. 2008;5(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang B, Shu XO, Delahanty RJ, Zeng C, Michailidou K, Bolla MK, et al. Height and breast cancer risk: evidence from prospective studies and Mendelian randomization. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(11):djv219. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norat T, Chan D, Lau R, Vieira R. WCRF/AICR systematic literature review continuous update report: the associations between food, nutrition and physical activity and the risk of breast cancer. London: Imperial College London; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denholm R, Hipwell HJ, Doran JS, Busana MC, Schmidt MA, Jeffreys M, et al. Comparison of breast density measures using manual and automated segmentation of three-dimensional Magnetic Resonance images. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I, De Stavola BL, Perry N, Vinnicombe S, Swerdlow AJ, et al. Life-course body size and perimenopausal mammographic parenchymal patterns in the MRC 1946 British birth cohort. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(5):852–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeffreys M, Warren R, Gunnell D, McCarron P, Smith GD. Life course breast cancer risk factors and adult breast density (United Kingdom) Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15(9):947–55. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-2473-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andersen ZJ, Baker JL, Bihrmann K, Vejborg I, Sorensen TI, Lynge E. Birth weight, childhood body mass index, and height in relation to mammographic density and breast cancer: a register-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(1):R4. doi: 10.1186/bcr3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.dos Santos Silva I, De Stavola BL, Mann V, Kuh D, Hardy R, Wadsworth ME. Prenatal factors, childhood growth trajectories and age at menarche. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(2):405–12. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorensen HT, Sabroe S, Rothman KJ, Gillman M, Steffensen FH, Fischer P, et al. Birth weight and length as predictors for adult height. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(8):726–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trichopoulos D. Hypothesis: does breast cancer originate in utero? Lancet. 1990;335(8695):939–40. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91000-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trichopoulos D, Adami HO, Ekbom A, Hsieh CC, Lagiou P. Early life events and conditions and breast cancer risk: from epidemiology to etiology. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(3):481–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Savarese TM, Strohsnitter WC, Low HP, Liu Q, Baik I, Okulicz W, et al. Correlation of umbilical cord blood hormones and growth factors with stem cell potential: implications for the prenatal origin of breast cancer hypothesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(3):R29. doi: 10.1186/bcr1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baik I, DeVito WJ, Ballen K, Becker PS, Okulicz W, Liu Q, et al. Association of fetal hormone levels with stem cell potential: evidence for early life roots of human cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(1):358–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trichopoulos D, Lagiou P, Adami HO. Towards an integrated model for breast cancer etiology: the crucial role of the number of mammary tissue-specific stem cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(1):13–7. doi: 10.1186/bcr966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boyd NF, Dite GS, Stone J, Gunasekara A, English DR, McCredie MR, et al. Heritability of mammographic density, a risk factor for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(12):886–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ursin G, Lillie EO, Lee E, Cockburn M, Schork NJ, Cozen W, et al. The relative importance of genetics and environment on mammographic density. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(1):102–12. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stone J, Dite GS, Gunasekara A, English DR, McCredie MR, Giles GG, et al. The heritability of mammographically dense and nondense breast tissue. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(4):612–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sellers TA, Vachon CM, Pankratz VS, Janney CA, Fredericksen Z, Brandt KR, et al. Association of childhood and adolescent anthropometric factors, physical activity, and diet with adult mammographic breast density. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(4):456–64. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorgan JF, Klifa C, Shepherd JA, Egleston BL, Kwiterovich PO, Himes JH, et al. Height, adiposity and body fat distribution and breast density in young women. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14(4):R107. doi: 10.1186/bcr3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Hsieh CC. Is maternal height a risk factor for breast cancer? Eur J Cancer Prev. 2013;22:389–90. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32835b6a82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pearce MS, Tennant PW, Mann KD, Pollard TM, McLean L, Kaye B, et al. Lifecourse predictors of mammographic density: the Newcastle Thousand Families cohort Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(1):187–95. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1708-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lokate M, van Duijnhoven FJ, van den Berg SW, Peeters PH, van Gils CH. Early life factors and adult mammographic density. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(10):1771–8. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]