Abstract

Objectives To find out which groups of people would use a National Health Service walk‐in centre that would offer mainly health care advice, staffed by nurses. To understand the circumstances in which people would use a walk‐in centre and to ascertain to what extent it would meet patients’ expressed health‐care needs.

Design A postal survey of 2400 people plus 27 semi‐structured interviews and one focus group.

Setting and participants The study was conducted in Wakefield, Yorkshire UK, and included both white and ethnic minority groups.

Results Most people reported that they would use a walk‐in centre. It would be more attractive to young as compared with older people, ethnic minority as compared with white people, people who are dissatisfied with access to NHS services and people with urgent health‐care problems. People want a wide range of services, including diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and general information. People also want access to both doctors and nurses, to male as well as female practitioners, to counsellors and interpreters. The type of service planned for this walk‐in centre will meet some of the expressed needs. However, patients’ expectations of the walk‐in centre exceed planned provision in a number of key respects.

Conclusion Walk‐in centres without GPs and with limited services will disappoint the public. It is important that walk‐in centres are evaluated and attention paid to ‘local voices’ before additional money is allocated for such centres elsewhere.

Keywords: access to care, ethnic minority, lay involvement, walk‐in centres

Introduction

Much has been written about the ‘democratic deficit’ in the NHS 1 , 2 and debates about the nature of public participation in health‐care decisions go back many years. 3 The Local Voices initiative, launched by the government in 1992 4 urged health authorities to be more responsive to the needs and preferences of local people, and to involve the public in the purchasing process. Since then some health authorities have consulted widely on their purchasing plans, using a number of methods to gather information. 5 However, few studies have examined people’s expectations and needs for a specific service before it has been introduced, and when local people’s views have conflicted with those of health‐care professionals, they have tended to be overridden. 3

In general practice, patients have not traditionally had a strong voice in decisions about service organization and delivery. Although the patient participation group movement has been in existence since 1972, the movement has failed to live up to its initial promise. 6 , 7 In the 1990s, fund‐holding arrangements and locality commissioning gave some GPs experience of assessing need, and a number of practices sought patients’ views and made changes to various services. 8 Nevertheless, it remained the case that few GPs were involved in population needs assessment. 9 The Labour Government’s 1997 White Paper for England, The New NHS, 10 conveyed the message that health‐care professionals are in the best position to make key decisions about resource allocation. However, in 1999 The Department of Health issued a policy statement emphasizing the importance of patient and public involvement in the new NHS. 11

The government is also concerned about patients’ access to health‐care. The recent National Survey of NHS Patients, conducted in 1998, found that 25% of people have to wait 4 days or longer for an appointment with their GP, and 19% of patients thought they should have been able to get an appointment sooner. 12 In spite of opposition from many members of the medical profession 13 , 14 the Government has responded to perceived public demand for easier access to primary health‐care by funding 36 NHS walk‐in centres, at a cost of over £30 million. The Government hopes that this new form of primary health‐care will offer people fast, flexible, convenient access to information and treatment for minor conditions, and that they will be sensitive to the needs of local people. 15 , 16 When the Department of Health drew up the criteria to be met by pilot sites wanting funding for the new NHS walk‐in centres, a population needs assessment component was included. Specifically, the Government called for ‘a patient/population needs assessment which supports the development of an innovative primary care centre and is sensitive to age, culture and lifestyle of patients. 17

It is in this context, that a group of general practitioners, GPs on call, who run the out‐of‐hours service in Wakefield, commissioned research into whether or not people living in the city would use a National Health Service walk‐in centre. GPs on call planned to open one of these walk‐in centres in May 2000. No appointments would be needed. In 1999, when GPs on call drew up their plans for a walk‐in centre, they envisaged a centre staffed by nurses, but linked to local GP services, and one that would mainly offer health‐care advice.

In support of their application to open a walk‐in centre, GPs on call consulted with a wide variety of organizations, which produced a positive outcome. They also asked researchers at the National Primary Care Research and Development Centre, University of Manchester, to conduct a more detailed piece of research. The research aimed to find out which groups of people would be most likely to use a walk‐in centre, and to understand the circumstances in which people would use it. Although seeking the views of disadvantaged groups may be a particular challenge 18 GPs on call were especially keen to hear the views of the ethnic minority, who comprise about 1.5% of Wakefield’s population. 19 This paper reports the results of this research, which included a large‐scale survey, semi‐structured interviews and one focus group discussion. While the findings have been summarized elsewhere 20 this paper reports both quantitative and qualitative results in detail. The project was carried out between September and December 1999.

Methods

The survey

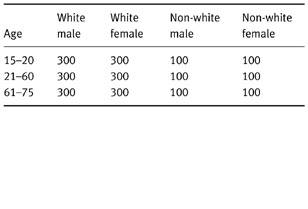

The intention was to draw a random sample of 2400 residents in central Wakefield, stratified by age, sex and ethnic status. However, due to the technical limitations of the Health Authority’s computing system, the authors were unable to draw such a sample. Patients were, therefore, selected in the following manner. They were separated into groups according to sex and age. The desired sample was then chosen by manually selecting blocks of records within each age‐sex group. This constituted the white sample (see Table 1), which would have included a small number of non‐white patients. The non‐white sample was selected by first identifying common Asian surnames and then sampling records in the same way as described for white patients.

Table 1.

The sample that was planned

One quarter of the questionnaires was sent to the ethnic minority group, partly because the research team anticipated a fairly low response rate from this group of people, and partly because GPs on call particularly wanted to hear the views of the ethnic minority (see Table 1).

Having obtained ethics committee approval, letters and questionnaires were sent to named individuals. All documents were translated into Urdu for people whose surnames suggested that they might not read English. Reminder letters and second questionnaires were sent to all those who did not respond initially.

The questionnaires asked for the following information:

• Age, sex and ethnic group.

• Views about: the types of services, opening hours and location of the proposed walk‐in centre; how it should be advertised; and whether information from walk‐in centre visits should be sent to GPs.

• Information about previous health problems which had led to consultations with GPs, A & E services, NHS Direct or other NHS services in the past 6 months and whether these would have been taken to a walk‐in centre had one been available.

By asking people to comment on problems they had actually experienced, the questionnaire provided a more accurate picture of walk‐in centre use than could be achieved using other methods (such as open questions about intended use or hypothetical scenarios). Data were coded and analysed using the software package SPSS Data Entry. The significance of associations between variables was assessed by Chi‐Square test or Fisher’s Exact test where appropriate.

The method used for the qualitative research

The purpose of the qualitative study was to explore the context and meaning of the results of the survey, and to probe more deeply into factors affecting the likely use of the walk‐in centre. 21 , 22 The respondents for the semi‐structured interviews were purposefully selected. 23 Many people volunteered for an interview when they completed their questionnaires and about half those selected for interview were chosen from those who had volunteered in this manner. Care was taken to select younger and older men and women, and people from different social backgrounds. For example, an effort was made to select respondents from affluent suburbs as well as those who lived in poorer areas and council estates.

Few non‐whites volunteered for an interview, and only one person of South Asian descent gave a contact telephone number. Thus, all except three of the interviews conducted with non‐whites were arranged via contacts with community workers based at Wakefield Asian Welfare Association. Altogether, 27 interviews were conducted, 15 with white people and 12 with people of South Asian descent. Just over half of the Asian respondents were born in Pakistan. The others had parents who were born in Pakistan. A focus group discussion also took place with a group of seven women who all came from Pakistan, and who only spoke Punjabi or Urdu.

All of the interviews conducted with the white respondents were conducted in their homes. Most of the other interviews and the focus group discussion were conducted at the Wakefield Asian Welfare Association Community Centre. People signed consent forms before the interviews if they had not already given their consent at the end of the questionnaires. An interpreter was used for the group discussion and for one of the interviews. All the interviews were recorded on tape, with the respondents’ permission. Most interviews lasted about 30 min, and the group discussion lasted about 1 hour.

After each interview notes were made of important points, and emerging themes identified. Later the tapes were re‐played several times, and relevant sections were transcribed. Key themes or categories were identified, and sections of text were grouped together by theme with the help of the word processing program, Word for Windows. 24

The results of the survey

Only limited conclusions can be drawn from the survey, partly because the sample was not a random sample and partly because only 811 questionnaires were returned (34%). Despite these limitations, the sample yielded a good spread of responses from people of all age groups, both sexes and across ethnic groups.

Most of those who returned a questionnaire indicated that they would use a walk‐in centre in Wakefield. When asking people to comment in general, in an open‐ended manner, about the services they would like to have at a walk‐in centre 75% reported that they would like a diagnosis, and 75% wanted treatment for health problems. Fewer people wanted information about self‐care or health promotion (45%) and only 41% wanted information about which health service to use for particular health needs.

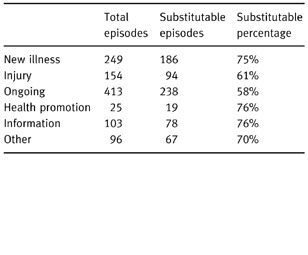

People were also asked whether or not they might have used a walk‐in centre as a substitute for actual consultations they had had with their GP or other health services over the past 6 months. Table 2 shows the types of problems for which people would substitute a walk‐in centre. People reported that they would be least likely to substitute walk‐in care for ‘ongoing’ health problems. However, as ‘ongoing problems’ were the most common type of problem (see Table 2 below), these might constitute the bulk of walk‐in centre work.

Table 2.

The types of problems for which patients reported that a walk‐in centre would be a substitute

It is possible that the sample was biased towards high users of health services generally and excluded those least likely to use a walk‐in centre. Estimates of walk‐in centre use are, therefore, likely to be exaggerated. Nonetheless, even if actual use was half that reported, it can be confidently predicted that about a fifth of the local people are potential walk‐in centre users.

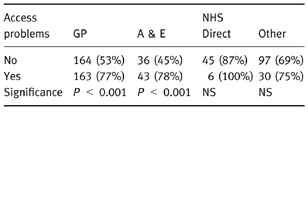

Sample limitations are less likely to have prejudiced analysis of the factors affecting walk‐in centre use. Flexibility in access was viewed as a key advantage of the new system, and people reported that they would be more likely to use a walk‐in centre when they had problems accessing other services. For example, 77% of those who found it hard to make an appointment with their GP thought they would use a walk‐in centre, but only 53% of those who had good access to a GP indicated that they would try this new form of service (see Table 3).

Table 3.

No (%) with/without access problems who would substitute a walk‐in centre for other services

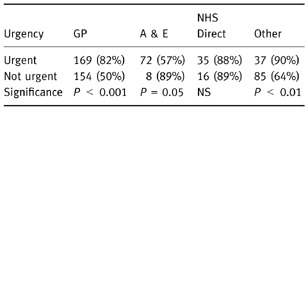

The survey also showed that people would be more likely to use a walk‐in centre for ‘urgent’ problems that they might otherwise take to their GP or other providers (Table 4).

Table 4.

No (%) who would use a walk‐in centre as a substitute for urgent/non‐urgent problems

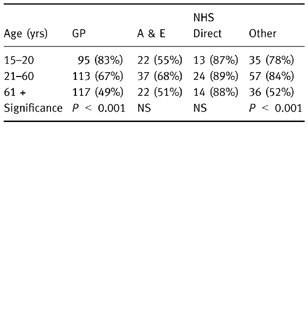

The survey also showed that young people would be more likely to use a walk‐in centre than elderly people. For example, the table below shows that 83% of those aged 15–20, who had consulted their GP during the previous 6 months, would consider using a walk‐in centre as a substitute for their GP. However, only 49% of those over 61, would consider using a walk‐in centre as a substitute for a GP (see Table 5).

Table 5.

No (%) in age group who would use a walk‐in centre as a substitute for their GP or other services

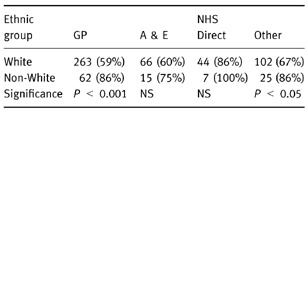

The survey also showed that non‐white patients would be more likely than whites to substitute a walk‐in centre for their GP or other providers (see Table 6).

Table 6.

No (%) of ethnic group who would use a walk‐in centre as a substitute for other services

However, these differences may partly be explained by the fact that ethnic minorities were significantly more likely than whites to have had urgent consultations with GPs (62% of non‐white sample vs. 37% of white sample), and to have had problems in gaining access to GPs (51% of non‐white sample, vs. 39% of white sample). Urgency was itself related to access, in that people with urgent problems were more likely to report problems with access (access problems for 49% of people with urgent problems, vs. 34% with non‐urgent problems).

The results of the semi‐structured interviews

The qualitative research complemented the quantitative approach and confirmed some of the results of the survey (triangulation). 25 The semi‐structured interviews and focus group shed further light on why certain groups of people reported they might use a walk‐in centre in Wakefield and what services they were expecting.

People’s expectations of a walk‐in centre

It appears that people’s expectations of a walk‐in centre were shaped by their previous experiences of health‐care. Some people seemed to expect a wide range of services and many of those interviewed said that they thought that a walk‐in centre would be staffed with both doctors and nurses. For example, a man of South Asian descent said that he had heard about walk‐in centres on the news. He commented:

It would be something similar to a doctor’s surgery. I think the only difference, from what I’ve heard, would be that it would not be your own GP, it would be a doctor. I don’t know, to be honest with you, all the ins and outs of what is actually going to be in there, whether its just going to be like a doctor’s surgery, or whether they are going to have, like we normally have, women’s clinics and physiotherapy and all that now at the doctor’s surgery. I don’t know how far they are going to go with it. (Interview 9).

However, although at least half of those interviewed said they were expecting to find a doctor at a walk‐in centre, a few people said that they were expecting to find a centre run by nurses. For example, a retired accountant said that he perceived that the centre would be a place for a ‘first call’, where you would get an opinion before seeing a GP. He seemed to think that nurses only deal with minor problems. He concluded:

Hopefully something like this would take the pressure off the GPs or the health service in general, so that the people who are really sick can be seen quickly. (Interview 4).

One other man thought that walk‐in centres would be run by nurses. His comments also suggest that attitudes to staffing are related to people’s perceptions of doctors’ and nurses’ roles, and it is clear that this man was not entirely pleased about the government’s proposals:

I understood that it would be just nurses, but whether this is so or not, I don’t know. If it was just nurses, well all they can do is just attend to basic needs, can’t they, you know, bandage up a sprained ankle or something of that nature. If there are no doctors you can’t get anything positive really, can you? (Interview 16).

This man’s concern about nurses may reflect a generally held view that nurses cannot replace doctors. Some people are not aware that nurses can prescribe a limited list of medicines and that they can initiate treatment. People’s perceptions of a nurse‐led service may change when they have actually experienced this new form of health‐care. A recent study has shown that people living in a highly deprived area were most enthusiastic about their nurse‐led practice once they had experienced the service for a few months. 26

One elderly white woman said that she had heard about walk‐in centres on the television. She liked the idea of a nurse‐led service, apparently based on her own experience. She commented:

To be honest, some of the nurses know as much as some of the doctors. (Interview 25).

Reasons why people thought they would use a walk‐in centre

Better access to female practitioners and interpreters

As noted in the White Paper, The New NHS, various barriers to health‐care may exist, particularly due to poor access to certain services. For example, women may find it hard to make appointments with female GPs and gynaecologists, and this may be particularly distressing to women from certain ethnic minority groups. 27 , 28

In Wakefield, people of South Asian descent saw a walk‐in centre as a means of gaining access to female practitioners. A male taxi driver pointed out that his wife wanted to see a woman for gynaecological problems and he commented:

Obviously if there is not a lady doctor for that sort of problem then a nurse is better than nothing (…). If they are just trying qualified nurses in the beginning, or permanently, does that mean they are cutting down work from doctors to nurses? Basically I am happy with this idea and I hope it works. (Interview 8).

Another man of South Asian descent said that women had to wait 3 or 4 weeks to see a female doctor at his surgery, and he concluded:

Sometimes for gynae problems ladies are facing very very serious problems to express their views. (Interview 7).

Sometimes access to care is hampered because of communication difficulties. 27 , 28 Some of the ethnic minority in Wakefield suggested that interpreters should be easily available. In particular, elderly women of South Asian descent said that there should be someone who could translate Punjabi when necessary.

Better opening hours

Some people perceived that the walk‐in centre’s opening hours (7am‐7pm) would be convenient because of work commitments. For example, a man of South Asian descent, a postman, explained why he would like a walk‐in centre:

Basically it would be the convenience of it, fitting my visit to the doctor round my work commitments. Because sometimes if you phone up a doctor now, it may be 4 or 5 days before the appointment that they give you, unless it is an emergency appointment. I’d like to be able to go in when I want, so it would be fitting in with my own sort of work, rather than working round the doctor’s surgery times, so they would be fitting in with my schedule rather than the other way round. (Interview 8).

A walk‐in centre seen as complementary to general practice

During the interviews some people said that they did not want to bother their doctors with minor problems, but they would use a walk‐in centre for reassurance. An elderly white woman explained:

I thought it would be a good idea if people hurt their hand, or just things that they don’t want to take to the doctor, yet they are worried. Going to the walk‐in centre, just to have it checked, and then if they say, “Well I think you should have further checking”, they could make an appointment to go to the doctor’s. (Interview 25).

A walk‐in centre as a substitute for general practice

During the interviews many people, particularly women of South Asian descent, complained that they had to wait much too long to get an appointment to see their GP for conditions such as arthritis. They did not want to tell the receptionists at the surgery that they had an emergency, nor did they want to wait days, and sometimes weeks, for an appointment to see a doctor. These women perceived that they would be able to consult a doctor more rapidly at a walk‐in centre than at their own surgery. Thus, they envisaged using the walk‐in centre as a substitute for their own GP. During the focus group discussion the interpreter said:

They [the women] do have access to female GPs now, but they can’t get an appointment. They are not happy with the receptionists and the system. They feel that the receptionists do not understand them. They are saying that they find it difficult at the doctors because there is nobody there who understands their problems. And this lady says she would rather go to the walk‐in centre, because you wouldn’t need an appointment, so if she was in pain… but she would need transport to get there. (Interpreter).

Another young woman of South Asian descent explained why she might want to use a walk‐in centre:

If I was in a lot of pain, sometimes you need to know about it, because it might not kill you but then again it might be something serious. And you know that if you ring your doctor, either you get a home visit, and really you only want that if you are dying, and since you’re not you feel a little bit guilty, and you don’t want a home visit, but to get an appointment you are going to have to wait 3–4 days, and so you think, something like this [a walk‐in centre], at least I can go and sit and wait and I shall be able to be seen by a doctor. (Interview 12).

Walk‐in centres would provide anonymity and privacy

Some GPs have negative views about walk‐in centres, 13 fearing that these centres will not provide the continuity of care that they see as important. However, some of those interviewed in Wakefield clearly want to consult a health‐care professional they have not known for years, and someone not known to the entire family. For example, one woman of South Asian descent explained that girls she knows like to go to the Family Planning clinic for advice because they do not want to be recognized. However, she said that the clinic was much too busy. She commented:

They [the girls] don’t want to see someone who hasn’t got enough time for them. They [the staff at the Family Planning clinic] never raise things for them, like teenage pregnancies, you know. Because a lot of my friends have babies, so I know how they feel, and they come and speak to us and say, ‘We’ve been to the family clinic and we want to see the doctor, but they say, Oh she’s busy, and we can’t see her’, so I think that would be a good idea [to have a walk‐in centre]. (Interview 11).

A white female college student also said that it would be good to speak to a female member of staff at the walk‐in centre about certain subjects. She said:

Sometimes you go to your doctor and it is a bit embarrassing because he has known you since you were knee high, or if you wanted to speak to a woman, because mine is a male doctor. (Interview 14).

A white male teenager also said that he might use the walk‐in centre to discuss things that he could not discuss with his own doctor, and an older Asian man expressed a similar view:

It might be good for personal problems, something real personal, like an infection of a sexual nature that you don’t really want to speak to your doctor about it (Interview 9).

Access to counselling

During the interviews a few people suggested that the walk‐in centre might be a particularly good place for those who had psychological problems or other worries. However, this implies that people think that a wide range of staff will be available for consultation. One white man, aged 30, said that he might use the centre for counselling because his own GP could not give him enough time to help him with his problems. He thought the centre would be particularly helpful after 6.00pm, when most GPs close their surgeries. This man pointed out that he had to wait 3 weeks for an appointment with a psychiatrist, and he thought that health‐care professionals based in a walk‐in centre might provide valuable help while he was waiting to see a consultant.

A young white woman also commented that her GP was much too busy to attend to her worries. She said that, ‘The GPs at the surgery tend to be writing the prescription out before you have even sat down’. She concluded:

If you need to talk you don’t want to feel that you only have your 5 minute slot. It would be nice if you could go after 6.00 pm and speak about what is worrying you. And sometimes you don’t want to trouble the doctor with trivial things, like if you are getting down, because of what ever, it would be nice to be able to speak to someone who can give you the time that you feel you need. (Interview 24).

Reasons why some may be reluctant to use a walk‐in centre

Privately run walk‐in centres have been portrayed in the media as places where middle class executives can obtain rapid access to care, perhaps on their way to work. However, this study shows that some people have a different image of NHS walk‐in centres, and two of the interviews shed light on why a few people may be reluctant to use the proposed walk‐in centre in Wakefield. One middle aged white woman explained:

You may get people who are on drugs, that sort of thing. (…) Some don’t like to see a doctor, but they might go and see a nurse and talk to somebody…. I think the general idea is good. It will relieve the doctors and help people who don’t like to see a doctor. Maybe nurses will be better for some people. (Interview 25).

An elderly white man admitted that a walk‐in centre might relieve the casualty department and GPs surgeries of what he called ‘time wasters’, but he had serious concerns. He commented:

If you put it in the town centre you are going to get all sorts of nutters just walking in. You are going get them being boozed up all night and they will walk in and say, “I’m fainting and doing this”, and you are going to get all the odd bods, in my opinion. (…). You’ll get the dossers going in because it will be nice and warm. They go in libraries and places like that so they are certainly going to go in there. (…) Where they are going to accommodate these people, goodness knows, it’s fairly busy now [at the medical centre]. (Interview 16).

Discussion

It is well known that postal surveys typically yield low response rates when used to elicit the views of local people about priorities for resource allocation for health‐care services. 5 Wakefield health authority once distributed 125 000 questionnaires, in order to consult the public on draft strategic plans, but only 50 were returned. 3 Thus, the team was not entirely surprised that the response rate for the survey was only 34%. Since the study was conducted with severe time constraints there was not enough time to post second reminder letters, and some of the ethnic minority may have found it hard to complete the questionnaires in either Urdu or English. However, although caution is important when interpreting the survey results, the postal survey combined with the qualitative research provided much useful and valid information.

The research showed that although a nurse‐led service, focused on health‐care advice, will meet a number of people’s needs, it will fail to meet the expectations of the great majority of potential users. People’s expectations of the proposed walk‐in centre exceeded planned provision in a number of key respects. People wanted a wide range of services, including diagnosis of new problems, management of new and ongoing problems, treatment for minor injuries, and counselling. As noted above, most people wanted access to doctors as well as nurses. Ethnic minorities indicated that an interpreter should be available since language was an important barrier to their use of health services generally.

It appears from the interviews that people’s expectations were mainly shaped by their own experiences of general practice. Some people may have read about privately owned walk‐in centres, which are usually staffed by doctors. Other people may have heard early Government announcements about NHS walk‐in centres, which originally stated that people would have the option of consulting a nurse or a doctor. 15

There remains substantial uncertainty about the place of walk‐in centres in UK primary health‐care. They have been established in response to perceived public concern about accessing conventional primary care services. This paper has shown that people may wish to use walk‐in centres for a number of reasons. It is also possible that some people will use walk‐in centres instead of their own GPs because they perceive that their own GP’s care is unsatisfactory. Previous research has shown that some people are afraid to change their GP, even when dissatisfied, for fear that some sort of action might be taken against them. 29 Thus, some people may regard a visit to a walk‐in centre as a legitimate way of consulting another GP when dissatisfied with care provided by their own doctor. However, walk‐in centres are being established in a way that will not meet many of the needs which people identify, including those reported in this paper. There is, therefore, a risk of a serious mismatch between what the NHS provides and what the public expects. Furthermore, walk‐in centres may well be overwhelmed with patients within a short period of time, if people expect more than can be provided.

It is far from clear that the best way to address deficiencies in primary care is to set up a new service. While some needs, such as those of commuters, may best be met by giving people access to services in more than one place, other needs might better be met by improving existing services. The way in which walk‐in centres will affect demand also needs to be considered. For example, NHS Direct has not produced an increase in demand for GP services as some had feared: indeed in areas where NHS Direct is operating, there has been a small reduction in demand for GP out‐of‐hours services. 30 However, the total amount of care provided (i.e. GP services plus NHS Direct) has increased significantly. Walk‐in centres may, therefore, push up overall demand for services. While some people are optimistic about the future of walk‐in centres 31 many GPs fear that they will increase NHS costs and demand for care. 13 , 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, –32 The interviews conducted in this study produced some evidence to support this latter view. Thus, the government needs to decide whether what is needed is better services, or more services, or both.

The Prime Minister has said he wants to speed up reform to the NHS and that, if the Labour party is returned to power, there will be a walk‐in centre in every major town and city. 33 However, the government has stipulated that all walk‐in centres will have to be evaluated after their first year of operation. 17 It is important that this evaluation looks at the place of walk‐in centres in the whole system of primary care, and does not just look at the new services in isolation. In this way it will be possible to design services which make the best use of available resources to meet patients’ needs. As part of this process, it will also be important to continue to hear users’ voices in deciding how to invest money more widely in new primary care services.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the people of Wakefield who gave up their time to complete questionnaires and to be interviewed. They would also like to thank Shirley Halliwell, Sarah Heyes, Malcolm Braim, Nabila Yasin‐Iannelli, Shazia Choudry and Mohammed Mobeen for their help with this study. This research was commissioned by GPs on call, Wakefield and Pontefract. It was also subsidised with money allocated by the Department of Health for the core programme of NPCRDC, University of Manchester.

Bibliography

- 1. Klein R & New B. Two Cheers? Reflections on the Health of NHS Democracy London: King’s Fund Publishing, 1998.

- 2. Davis H & Daly G. Extended Viewpoint: Achieving democratic potential in the NHS. Public Money and Management, 1999; 19 : 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cooper L, Coote A, Davies A & Jackson C. Voices Off. Tackling the Democratic Deficit in Health London: The Institute for Public Policy Research, 1995.

- 4. Department of Health . Local Voices: the Views of Local People in Purchasing for Health London: National Health Service Management Executive, 1992.

- 5. Coulter A. Seeking the views of citizens. Health Expectations, 1999; 2 : 219–221.11281898 [Google Scholar]

- 6. North N. Issues and Debates. A New NHS? Research, Policy and Planning, 1998; 16 : 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agass M, Coulter A, Mant D & Fuller A. Patient participation in general practice: who participates? British Journal of General Practice, 1991; 41 : 198–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rogers A & Popay J. User involvement in primary care. In: Boyd R, Butler T, Gask L et al (eds.) What Is the Future for a Primary Care‐led NHS? Oxford: Radcliff Medical Press, 1996.

- 9. Murie J, Hanlon P, McEwen J, Russell E, Moir D & Gregan J. Needs assessment in primary care: general practitioners’ perceptions and implications for the future. British Journal of General Practice, 2000; 50 : 17–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Department of Health . The New NHS. Modern, Dependable London: The Stationary Office, 1997.

- 11. Department of Health Patient and public involvement in the new NHS London: The Stationary Office, 1999.

- 12. Department of Health . National survey of NHS Patients: general practice 1998 London: The Stationary Office, 1999.

- 13. O'Connell S. Walk‐in! Walk out? What is it all about? British Journal of General Practice, 1999; 49 : 765–765. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mahony C. Doctors blast ‘airhead’ nurse‐led NHS schemes. Nursing Times, 1999; 95 (28): 11–00. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Department of Health . Up to £30 million to develop 20 NHS fast access walk‐in centres Press Release. 1999/0226 (13/4/99) www.doh.gov.uk 1999.

- 16. Department of Health . Frank Dobson announces more NHS walk‐in centres Press Release. 1999/0571 (30/9/99) www.doh.gov.uk 1999.

- 17. NHS Executive . NHS Primary Care Walk‐in centres: selection of pilot sites for 1999/2000. HSC /116 Leeds: Department of Health, 1999. http://tap.ccta.gov.uk/doh/coin4.nsf

- 18. O'Keefe E & Hogg C. Public, participation, and, marginalized, groups: the, community, development, model. Health Expectations, 1999; 2 : 245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ashrafi K & Brian A. Report of Ethnic Minority Women’s Health Project Wakefield: Wakefield Health Authority, 1997.

- 20. Chapple A, Halliwell S, Sibbald B, Roland M & Rogers A. A walk‐in? Now you’re talkin′. Health Service Journal, 2000; 110 (5703): 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greenhalgh T & Taylor R. Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). British Medical Journal, 1997; 315 : 740–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rogers A, Popay J, Williams G & Latham M. Criteria for Assessing the Validity of Qualitative Research from Within the Social Sciences London: Health Education Authority, 1997.

- 23. Coyne I . Sampling in qualitative research: Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1997; 26 : 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burnard P. Qualitative data analysis: using a word processor to categorize qualitative data in social science research. Social Sciences in Health, 1998; 4 : 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Morgan D. Practical strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: applications to health research. Qualitative Health Research, 1998; 8 : 362–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chapple A, Rogers A, Macdonald W & Sergison M. Patients’ perceptions of changing professional boundaries and the future of ‘nurse‐led’ services. Primary Health Care Research and Development, 2000; 1 : 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chapple A, Ling M & May C. General practitioners’ perceptions of the illness behaviour and health needs of South Asian women with menorrhagia. Ethnicity and Health, 1998; 3 (1/2): 81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chapple A. Iron deficiency anaemia in women of South Asian descent: a qualitative study. Ethnicity and Health, 1998; 3 (3): 199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Anon. Changing doctors without changing address. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 1986; 36 : 185–185. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Munro J, Nicholl J, O'Cathain A & Knowles E. Evaluation of NHS Direct first wave sites: Second interim report to the Department of Health Sheffield: Medical Care Research Unit, University of Sheffield, 2000.

- 31. Wilkie P & Logan A. Walk‐in centres: caution not cynicism. British Journal of General Practice, 1999; 49 : 1017–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Galloway M. Will walk‐in centres be a blessing or a curse? Doctor, 28 October 1999; 38–41.

- 33. Watson C. Blair: doctors must speed up reforms. GP, 8 October 1999; 3–3.