Abstract

Objectives To describe the methods used for involving consumers in a needs‐led health research programme, and to discuss facilitators, barriers and goals.

Design In a short action research pilot study, we involved consumers in all stages of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme: identifying and prioritizing research topics; commissioning and reporting research; and communicating openly about the programme. We drew on the experience of campaigning, self‐help and patients’ representative groups, national charities, health information services, consumer researchers and journalists for various tasks. We explored consumer literature as a potential source for research questions, and as a route for disseminating research findings. These innovations were complemented by training, one‐to‐one support and discussion. A reflective approach included interviews with consumers, co‐ordinating staff, external observers and other programme contributors, document analysis and multidisciplinary discussion (including consumers) amongst programme contributors.

Results When seeking research topics, face‐to‐face discussion with a consumer group was more productive than scanning consumer research reports or contacting consumer health information services. Consumers were willing and able to play active roles as panel members in refining and prioritizing topics, and in commenting on research plans and reports. Training programmes for consumer involvement in service planning were readily adapted for a research programme. Challenges to be overcome were cultural divides, language barriers and a need for skill development amongst consumers and others. Involving consumers highlighted a need for support and training for all contributors to the programme.

Conclusions Consumers made unique contributions to the HTA Programme. Their involvement exposed processes which needed further thought and development. Consumer involvement benefited from the National Co‐ordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment (NCCHTA) staff being comfortable with innovation, participative development and team learning. Neither recruitment nor research capacity were insurmountable challenges, but ongoing effort is required if consumer involvement is to be sustained.

Keywords: consumer involvement, health technology assessment, NHS R & D Programme, partnership, research agenda, research priorities

Background

The British NHS Research and Development Strategy was established in 1991 and has led to an R & D Programme which ‘aims to maximise the benefits for health of science and technology, and to apply research rigour to the problems confronting the NHS, public health and social services’. 1 The Central R & D Committee advises on the strategic direction of R & D by identifying and prioritizing the research needs of the NHS. It is currently supported in this work by four standing groups which cover (a) consumer involvement in NHS R & D; (b) health technology assessment; (c) service delivery and organization, and (d) new and emerging applications of technologies.

There is a growing enthusiasm for consulting consumers to inform the NHS R & D Programme at all stages from setting the research agenda to disseminating and implementing the findings. The term ‘consumer’ refers to people whose primary interest in health‐care is their own health or that of their family, as past, current and potential patients, users of services or carers, and people representing any of these groups through community organizations, networks, or campaigning and self‐help groups. 2 We use the term ‘consumer’ because of its accepted usage to describe people who are potential users of the health services. Recognizing the difficulties in identifying the most appropriate form of consumer input, and the consequent risk of consumer perspectives not being well addressed, the Central R & D Committee convened a Standing Advisory Group on Consumer Involvement in the NHS R & D Programme in 1996 (since renamed Standing Group on Consumers in NHS Research). 1

In this paper we report a short pilot study of consumer involvement in the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme undertaken in collaboration with the Standing Group on Consumers in NHS Research. The aim of the HTA Programme 3 , 4 is to ensure that high quality research information on the costs, effectiveness and broader impact of health technologies is produced in the most economical way for those who use, manage and work in the NHS [emphasis added].

Thus, the HTA Programme seeks to be a ‘needs‐led’ programme which consults widely in its five stages of work: identifying research topics; prioritizing, commissioning and reporting research; and in openly communicating throughout the NHS. Initial identification of research topics is through wide consultation and other methods. The Group prioritizes research needs with the help of six advisory panels covering the acute sector, primary and community care, diagnostics and imaging, pharmaceuticals, population screening and methodology of health technology assessment. Their deliberations are supported by the National Co‐ordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment (NCCHTA) which provides a scientific secretariat that takes account of the views of a wider range of experts in specific topic areas and is responsible for communicating openly about the programme. The HTA Commissioning Board then commissions high quality research to address the questions raised. Several hundred expert peer reviewers assist the Commissioning Board in reaching its conclusion on which of these best meet the needs of the NHS. The Standing Group on Health Technologies oversees the HTA Programme and provides advice on national priorities for health technology assessment. 4

In planning the pilot programme, previous personal experience of consumer involvement in research had led us to consider the following factors as essential for building and sustaining working partnerships of equals in health research: 5

• prior thought and discussion about the tasks to be addressed, the skills required and the people best able to fulfil them;

• identifying potential barriers to be overcome;

• identifying consumers and professionals and inviting their participation;

• allowing time for consumers to understand the history, organization and aims of the research and for professionals to understand the experiences, organizations and aims of the consumers;

• resourcing working partnerships to enable participation;

• training in skills for multidisciplinary teamwork; and

• ongoing evaluation.

Then we took into account these factors and also benefited from: the current political climate which encourages consumer involvement in research; 6 direct experience of consumer involvement in research elsewhere; 7 , 8, –9 and discussions with Consumers in NHS Research.

As an initiative in organizational development, the project was led by the NCCHTA Director (RM), who recruited an action researcher with experience of consumer involvement in research (SO) to join the staff of NCCHTA 1 day a week for a year. An advisory group brought to the work the perspectives of clinicians (TW), service users (PB), Standing Group on Consumers in NHS Research (JB) and broader policy and practice within the NHS R & D Programme (JG). Changes made in light of the pilot followed the usual discussion and management processes within the NCCHTA, including the NCCHTA steering group, the Standing Group on Health Technology and the NHS Executive.

This study was an action research pilot project to assess the resources, skills and organizational change needed to involve consumers in the five main stages of work of the HTA Programme. This paper describes how we involved consumers in the work of the NHS Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme, and what we learnt about facilitators, barriers and goals.

Methods

How consumers were involved

We sought consumers who had an understanding of the topic area, and were willing to give time and effort to undertake a specific task and discuss the process afterwards. We identified consumers opportunistically from campaigning, self‐help or patients’ representative groups, national charities, health information services and journalists. Some groups were already known for their use of research.

We recorded the process of enabling consumer involvement in the programme from the perspectives of the different people involved. Perceptions and interpretations of events are necessarily subjective, so we sought a broad range of views and invited staff, consumers and panel members of the HTA Programme to comment on their experience, either face‐to‐face, by telephone, post or E‐mail.

We invited interviewees to describe their experience of the HTA Programme and their perceptions of consumer involvement and what guidance may be useful for newcomers. We then asked them to consider to what extent their understanding of consumer involvement differed from their understanding of the involvement of others in the programme. Finally, we scanned the interview notes for issues which resonated or conflicted with issues raised in earlier interviews, and discussed these in more depth with the interviewees. In addition, all panel members, panel observers and consumers who had contributed to the HTA Programme during the pilot were invited to a 1 day meeting to reflect on the pilot.

Identifying important research questions

Ever since its inception, the HTA Programme has consulted widely for suggestions of research topics. Annual letters to clinicians and managers throughout the country have also been sent to some consumer organizations. Other routes have included developing an awareness for new and emerging technologies, systematic scanning of reviews for research recommendations and the HTA Programme’s WWW site. 10

Previous methods within the HTA Programme for consulting consumers as to what research is needed have had little success, so we explored innovative methods for identifying research questions from the perspective of consumers during the pilot. These comprised:

• drawing on questions asked of the national free phone help line to consumer health information services (0800 665544);

• discussing research needs with consumers; and

• reviewing qualitative research undertaken by consumers.

Prioritizing research

Prioritizing and refining research questions is the task of the Standing Group on Health Technology and its six advisory panels. Two consumers joined each of three panels. An induction day helped people prepare for their role as panel members. We invited all new panel members (whether bringing a consumer perspective or not), panel chairs and panel observers from the Standing Group on Consumers in NHS Research.

The programme included an activity from the VOICES project 11 to encourage multidisciplinary teamwork, an introduction to the NHS R & D Programme and the HTA Programme, a discussion about turning problems into research questions, and an introduction to critical appraisal 12 , 13 and the types of papers that would be discussed in panel meetings. The principle of working in equal partnership with consumers was modelled by inviting consumers to share leading roles during the day.

Consumers participated as full members of the three panels, discussing research topics and voting for their priorities. Between the first and second meeting of each panel, NCCHTA researchers prepared 15 brief summaries (vignettes) for each panel about research need to inform the prioritizing process. For the pilot study each panel researcher attempted to consult consumers in the preparation of at least one vignette. Names were suggested by consumer members of panels or observers from the Standing Group on Consumers in NHS Research.

Commissioning research

We selected four topics for consumer peer review where we knew or expected to find easily active consumer organizations. We drew on the expertise of a charity’s research department, a charity’s advisor with research experience, a health service user and campaigner with self‐taught research literacy, and a health service user without previous experience in research or consumer representation.

Reporting research

When commissioned research is completed a full report is requested from the research team and is edited and peer reviewed before publication as part of the HTA monograph series. We offered two draft final reports to consumers for review. One was reviewed by a member of a national consumer group, with a personal interest in the subject. Another draft report was reviewed by a group of people within a charity with personal and professional interests in the subject.

Communicating openly

We sought opportunities to inform consumer networks about the HTA Programme at conferences, through regular updates of the pilot sent to consumers who have contributed in the pilot and other organizations whose primary purpose was to nurture consumer involvement in the NHS (the Patient Partnership Strategy Group, the Standing Group on Consumers in NHS Research, and Quality and Consumers Branch of the NHS Executive), and the HTA Programme WWW site. 10

Summaries of HTA research reports were available at conferences and we also mailed them to consumer organizations who were asked whether the reports were of interest, whether they could comment on the report, and whether they would use the report to inform or support health service users. They could request a copy of the full report should it interest them. The Centre for Health Information Quality maintains a database of people and projects addressing evidence‐based patient information. We registered the HTA Programme there to attract attention to HTA funded research as valuable resources for such work.

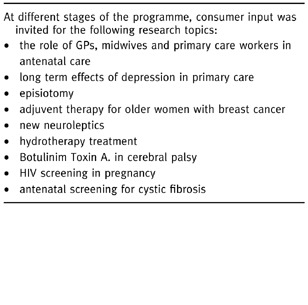

Overall, the pilot involved consumers undertaking different tasks across a range of research topics (see Box 1).

Table Box 1.

Analysis

The action researcher (SO) reviewed the experience of involving consumers in each task of the HTA Programme in order to identify factors which either facilitate or hinder consumer involvement. Materials available for analysis included: policy and procedural documents of the NCCHTA; agenda and minutes of meetings of the HTA and the NCCHTA; documents produced for the pilot, such as letters to consumers and training materials; documents produced in response to the pilot, such as observations of panel meetings (2) and staff meetings (2) and the meeting convened to reflect on the pilot; feedback about the pilot from consumer observers (9 occasions), consumer panel members (7 occasions), other panel members (9 occasions), other consumer contributors (11 occasions), NCCHTA staff (12 occasions) and panel chairs (2 occasions). This feedback was in the form of one‐to‐one meetings (5); telephone calls (19); E‐mail messages (6); letters (5); questionnaires (14) and group discussions with NCCHTA staff (3).

From these materials the action researcher identified facilitators, barriers and tensions encountered when involving consumers. From these she deduced the resources, skills and organizational change needed to involve consumers as active partners in the work of the HTA Programme. With such a small study, there was no independent analysis, but the findings were presented at the meeting of the HTA contributors convened to reflect on the pilot, and developed in light of discussion there. Co‐authors discussed the analysis in the light of their direct experience of the pilot and their attendance at the reflection day.

Results

Facilitators

Innovation

Since its inception the NCCHTA has continually sought to develop new processes for providing administrative and scientific support to the HTA Programme. Consumers commented favourably on this experimental and reflective approach and supported the principle of learning by doing rather than letting time pass while planning in a vacuum.

Participative development and team learning

The action researcher observed regular ‘whole team’ meetings about the work of the NCCHTA and the NHS R & D Programme where staff had the opportunity to discuss current issues and decisions, and exchange ideas and views. Adding consumer involvement to their list of tasks increased their workload, but did not fundamentally challenge an open working culture that was already receptive to listening to the views of others. Indeed, the pilot has raised some issues about consumer involvement, particularly recruitment, support and training, conflicts of interest and documentation which may be important to other participants.

It [consumer involvement] has made things change very quickly. Raising these issues is not criticising the programme but part of its development. [NCCHTA staff].

A key approach to successful integration of consumers seemed to be a willingness to learn from each other and from practical experience. In this regard, the pivotal role of the NCCHTA was appreciated by consumers. They were particularly impressed by

the feeling of commitment to the project from a range of National Co‐ordinating Centre for HTA staff. [consumer panel observer].

However, these limited opportunities for participative development have not reached all panel members and expert contributors, some of whom may feel excluded from influencing development.

Learning from others

Learning from others was a recurring theme of the pilot. New panel members learnt from their more experienced colleagues, and brought lessons for the HTA Programme from their wider experience. The HTA Programme has also learned from the experience of other initiatives, such as the VOICES project, 11 a training programme for consumer involvement in maternity services, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme 12 , 13 and the Standing Group on Consumers in NHS Research.

Discussion at the reflection day emphasized this theme. The HTA Programme was seen as one of many organizations trying to actively involve consumers in the research process. Sharing experiences with other research organizations such as the Medical Research Council, and other national and regional NHS research programmes (especially the Standing Group on Consumers in NHS Research) was recommended for more efficient development.

Training and support

New panel members, whether consumers or not, appreciated the induction day, but found this was only a beginning to a long apprenticeship, and would appreciate on‐going support for panel members, perhaps through a system of mentorship. Support suggested for consumer peer reviewers included: practice peer review sessions (professional peer reviews might also benefit); someone to phone when perplexed; and opportunities to meet others every 6–12 months.

Some consumers could provide their own support. For instance, some feel they would be relieved of a ‘hefty responsibility’ if they were allowed to consult with colleagues before responding to consultations. This raises the issue of confidentiality which needs to be balanced with the benefit of providing peer support for consumers touched by the research topic in question, which sometimes carried personal connotations.

[The research topic] is an extremely important but sensitive issue for each of these users. They found reading the report an emotional experience and have each taken time to think through their comments which are presented here in a reasoned form. The strength of feeling aroused by this report amongst users should not be underestimated. [National charity staff].

Managing change

Managing the integration of consumers was the responsibility of the NCCHTA staff and panel chairs, who were considered key to the process of integrating consumers as panel members. The Standing Group on Consumers in NHS Research stressed in a letter

the need to ensure that the chair of any panel/group is encouraged to be particularly sensitive to the needs of consumer members and to ways in which other members respond to them.

The impending pilot was discussed with panel chairs in advance and most made consumers feel very welcome at panel meetings. Panel chairs steer their colleagues through a heavy workload. To what extent they also manage to nurture the group dynamics is unclear. This is particularly challenging when bringing together multidisciplinary groups from across the country only twice a year.

Barriers and tensions

Cultural divisions

Consumer panel members found that the complex organization of the NHS R & D Programme, unfamiliar processes, acronyms and technical language presented barriers to full participation. We tried to bridge the gap between consumers and others at the induction day and by the circulation of background papers for consumers to understand the history, organization and aims of the HTA Programme. However, the complementary principle of allowing the professionals time to understand the experiences, organizations and aims of the consumers has only been addressed so far by those with direct responsibilities for recruiting consumers. In addition, focusing attention on support and training for consumers has provoked concerns about ‘reverse discrimination’.

For some panel members, working as a committee with professional and consumer members was a new experience. Both consumers and professionals have sometimes felt wary and defensive when participating in this new initiative, and this has impeded communication. Airing mistakes and difficulties has relieved tensions. Despite these difficulties, consumers have made very helpful and timely contributions to clarifying and prioritising the knowledge gaps. They have emphasized aspects of research which would otherwise be glossed over, and provoke different ways of thinking.

Most comments from panel members were welcoming of the newcomers, for instance:

My general impressions were that consumer representatives have been making important and quite frequent contributions to the panel… Their contributions are always valued and carefully listened to… [I] think consumer involvement here has been very successful.

In contrast, a member of the same panel was alone in expressing decidedly negative opinions about consumer involvement:

I was concerned that the “patient” and “consumer” type representatives seemed to have a very shallow understanding of medicines and clinical science which leads to the danger that the wrong questions will be asked… I have no doubt that the experience for those persons was of value but I am not convinced that they added much… if anything to the discussions.

Cultural divisions were not necessarily between consumers and professionals, but also between experienced HTA contributors and newcomers. Generally, consumers were unsure of their responsibilities within HTA, they faced language barriers, and needed a quiet apprenticeship, adequate time, better briefing, training and on‐going support. These problems (discussed in more detail below) were not unique to consumers, but they felt them more acutely.

A panel observer from the Standing Group on Consumers in NHS Research suggested that improving the processes within panel meetings may start by defining the roles of the people within the group and considering the different ways in which people may be marginalized: for instance, belonging to a minority ethnic group, being the only woman, or only man, only consumer or only non‐clinician in a group.

Language

Language was repeatedly mentioned as a barrier to consumer involvement. Specialist jargon in a panel meeting can be alienating, but business may be impeded if everything was to be ‘translated’ into non‐specialist language.

Consumers suggested they would benefit from a glossary or a medical dictionary when peer reviewing reports. They would also appreciate being able to telephone someone for an explanation if they did not understand. Knowing consumers were using their work to make important decisions, NCCHTA staff were motivated to write more clearly and explain acronyms, diseases and technologies in the papers prepared for panel meetings.

It is not only medical terminology that creates barriers, but management and committee terminology, and voluntary sector terminology. ‘Executive’, ‘speaking through the chair’, ‘secondary publications’, ‘trajectory’ and ‘diffusion curve’ were all raised as terms which have perplexed consumers. Other misconceptions and inaccurate assumptions arise from the terminology used by and about lay people: consumer, service user and user representative are sometimes used interchangeably despite their different meanings and associations. Such confusions are not always predictable and there is a need to check constantly that participants of a discussion have understood.

Recruitment

The choice of consumers was a sensitive issue during the pilot. Consumers themselves have recommended using Help Box, 14 Community Health Councils, self‐help groups, carer groups, advocacy groups, community care groups, practice patient participation groups and Local Research Ethics Committees.

However, when following such leads it was often difficult to distinguish between consumer groups and charities led by professionals offering information to patients. Approaching groups and networks to find willing individuals within them for particular tasks was also very time‐consuming. Advertising in the national press has also been recommended, but not tried during the pilot.

Research capacity

In the pilot study, scanning consumer research literature yielded few recent recommendations for research that also fell into the scope of the HTA Programme. Similarly, records of questions about treatment choices to Consumer Health Information services were inadequate for identifying potential research topics. A more fruitful way of identifying research questions that are important to consumers was to discuss it with them face‐to‐face. At the reflection day it was suggested that consumers have a huge knowledge base and recognize the knowledge gaps, but don’t call these research questions and they may benefit from help in translating their vague ideas into research questions.

Skills

Panel members needed both technical skills and skills in multidisciplinary teamwork. Some consumers offered coherent arguments, combining opinion and research findings, to the task of refining research questions whether at the stage of writing the vignette or peer reviewing research proposals. Some panel members saw seeking consumer views through qualitative research as optional extras to professionally defined questions assessing technologies, not realising that consumer involvement could influence how technologies are assessed, for instance by suggesting other outcomes of interest.

Time and resources

Supporting consumer involvement required additional time and resources: access to current literature (published and unpublished) by, for and about consumers; lists of consumer groups; training materials; and time to follow consumer networks, recruit consumers, develop training and adapt materials for a wider readership. In addition to this were the costs incurred by consumers and the fees it may be appropriate to pay for their time. A consumer who peer reviewed a proposal said:

I thought if they offered an honorarium, I’d give it to the [consumer organization]. It was at least a day’s work with looking up the references. How much do they value it? It’s something they ought to consider.

Discussion

This was a small study without specially allocated funding for evaluation, where efforts to involve consumers and learn from the experience were largely opportunistic. As such it resembled an organizational development project, rather than an in‐depth sociological study. An action researcher was allowed 1 day a week to introduce changes, invite feedback from those involved and present progress reports for wide discussion. Subsequent changes were influenced by the progress reports, the discussions they provoked, the personal experience of the pilot of those with responsibility for management decisions, and financial and workload constraints of running the HTA Programme.

Each stage of the pilot revealed new benefits and hurdles associated with consumer involvement in a research programme. Such a small study cannot be expected to have exhausted the consequences of consumer involvement, and a developmental approach must continue if consumer involvement is to be sustained and improved.

We discuss here the implications of involving consumers for resources, skills and organizational change that were evident from the experience of the pilot or were raised at the reflection day.

Resources

People, both consumers and those within the programme working with them, were the most valuable (and costly) resource for bringing a consumer perspective to the programme. We introduced six consumers to advisory panels; invited five others to comment on research need; four to comment on research proposals; and two to comment on draft reports. This left two panels, and nearly 100 vignettes, 40 draft reports and 100 full research proposals each year without planned consumer involvement.

Building on the pilot, we are now recruiting a wider pool of consumers who are convinced that research is important to them, that it can serve their information needs and support their interests. Job descriptions and person specifications have been prepared to facilitate appropriate recruitment. In line with NHS policy, consumers are able to claim travel expenses, overnight subsistence, and child‐care or other carer costs and a fee for attending panel meetings (£122.00 for a day) paid in the event that they are self‐employed; not in paid employment; or will lose a day’s pay by virtue of attending the meeting. Staff costs include a new half time post at the NCCHTA to allow time for identifying, recruiting and supporting consumers involved in all aspects of the HTA, and a 0.1 post for an external advisor.

Skills

Language within the HTA Programme is largely technical and contributions from those outside the programme are increasingly encouraged via electronic mail and the WWW. It was evident from the pilot that those consumers best able to make an impact are those who not only bring a well informed consumer perspective, but can also engage professionals in discussion in their own language and can make use of electronic communications. In addition, some consumers were skilled in framing research questions important to them in terms that would also allow them to be addressed by the HTA Programme.

Two possible, and complementary approaches, to meeting the need for appropriate skills is to train the consumers to participate in professional debates, and to train professionals to listen to consumers in their own terms. The challenge to consumers is to develop their own capacity as users of research to suggest research questions that are important to them, and to respond to requests to comment on research plans. To offer timely and relevant contributions to a research programme structured to suit the NHS, they need to build their own infrastructure: to co‐ordinate their research literacy skills, experience of health problems and services, emotional support, and internet and library skills.

The complementary challenge to NHS professionals is to enhance their own ‘bi‐lingual’ skills for discussing research with consumers and to emulate those who already recognize that consumer issues can shape research projects about effectiveness rather than be the subject of observational and qualitative study, to complement studies of effectiveness. For instance, interventions can be tested for their impact on physiological measures, with patients’ views being recorded simultaneously. Or, more radically, patients’ views can be sought in advance in order to determine what outcomes should be measured when evaluating interventions.

We found discussing research with consumers face‐to‐face was far more fruitful than reviewing their literature, or formally requesting suggestions for research. This relied on us travelling to meet the consumers at their base for ‘bi‐lingual’ discussions, rather than expecting consumers to adopt the usual working practices of the programme. Widely extending such exercises would be a considerable challenge for NHS R & D in terms of resources and organization.

Organizational change

A number of barriers and tensions within the HTA Programme were encountered during the pilot: time constraints; resources; use of language; recruitment; training and support; confusion about processes and roles; conflicts of interest; consultation and confidentiality; cultural divides; skill development and the need for a ‘safe’ learning environment. In addition, external hurdles impinged on the HTA Programme, including: accessibility of consumer groups; busy people’s workloads; consumers’ need to prioritize their efforts; and research capacity.

Addressing some of these barriers and tensions began during the pilot year, and others are being addressed as consumer involvement is developed further. Indeed, several consumers participating in the pilot were impressed by the NCCHTA staff and their willingness to listen to new ideas and to consider change in a positive light. From observing team meetings it was clear that these attitudes were not unique to the task of involving consumers, but built on attitudes that were shared by a number of NCCHTA staff: communicating well, developing innovative work as a team, learning from immediate experience and the experience of other initiatives and reflecting on past efforts in order to manage change. Being open to learning from experience and mistakes, from involving non‐traditional groups, and from the external environment makes the organization more adaptable in times of change and able to sustain and build on the changes they have made. 15

However, some resources, skills and organizational change are beyond the reach of the HTA Programme working alone and need to be considered in discussion with the Standing Group on Consumers in NHS Research, other R & D Programmes and consumers. For instance, policies about paying an honorarium to consumers and others who peer review documents or attend meetings need to be discussed with other R & D Programmes.

A concerted effort to develop consumer involvement simultaneously in parallel programmes would bring mutual benefit, especially when individual consumers may contribute to individual programmes only once. This would be particularly beneficial when developing training workshops and on‐going support for consumers and R & D managers. Economies of effort may also be made by combining some consultation exercises for a range of R & D Programmes, especially when identifying potential research topics. At the same time co‐ordinated effort may avoid consumer ‘consultation fatigue’.

Advancing consumer involvement raises two complementary questions: how can we meet the moral and political imperative of consumer involvement, and what is the impact? This paper has addressed the first question by reporting processes for involving consumers in the HTA Programme. To answer the second, we would like to know whether consumer involvement alters the range of research topics, or the framing of research questions, or the teams commissioned to undertake the research. A preliminary analysis will be reported elsewhere. 16 Briefly, when consumers were able to overcome the barriers, their contributions particularly focused on: confidentiality, consent to research and recruitment of research participants; language, information and support for approaching research participants; individualized health‐care and informed consent; social aspects of ill‐health and health‐care; the integration of users’ views; and the dissemination of research findings.

How consumers are involved and what impact they have may be related. Designing consultations to better suit consumers (for instance, in terms of setting, timetable, resources and language) may open the way to more fundamental changes for facilitating consumer involvement, rooting it more in the working practices of the voluntary sector rather than merely smoothing the path for consumer entrepreneurs infiltrating a structure set top‐down by the NHS Executive. Such efforts may also lead to a greater impact on the research agenda. Indeed, consumers may only continue to participate if they see their contributions integrated into the programme and having an impact on the subsequent research and generation of knowledge.

Acknowledgements

We are particularly grateful to the consumer groups, and individuals within them, who contributed to this pilot project: Age Concern London; Alzheimer’s Disease Society; Arthritis Care; Breastfeeding Network; CERES (Consumers for Ethics in Research); College of Health; Cystic Fibrosis Trust; Depression Alliance; Mental Health Foundation; MIND; Motor Neurone Disease Association; National Childbirth Trust; Ovacome; Patients’ Association; Prostate Cancer Charity; Prostate Help Association; Prostate Research Campaign UK; SCOPE; STIFF (UK); UK Breast Cancer Coalition. The Centre for Health Information Quality provided important information about consumer groups. Amanda Nicholas provided efficient administrative support.

Bibliography

- 1. NHS Executive . Research: What’s in it for consumers?: First report of the Standing Advisory Group on Consumer Involvement in the NHS R & D Programme to the Central Research and Development Committee 1996/7.

- 2. Blaxter M. Consumers and research in the NHS: consumer issues within the NHS. In: Consumers in the NHS: an R and D Contribution to Consumer Involvement in the NHS. UK: Department of Health, 1995.

- 3. Milne R & Stein K. The NHS R & D Health Technology Assessment programme. In: Baker MR, Kirk S (eds.) Research and Development for the NHS. Evidence, Evaluation and Effectiveness. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998.

- 4. NHS Executive . The Annual Report of the NHS Health Technology Assessment Programme 1998.

- 5. Oliver S & Buchanan P. Examples of lay involvement in research and development. London: Social Science Research Unit, London University Institute of Education, 1997.

- 6. Blaxter M. Consumers and research in the NHS. consumer issues within the NHS. In: Consumers in the NHS. An R and D Contribution to Consumer Involvement in the NHS. UK: Department of Health, 1995.

- 7. Oliver S. How can health service users contribute to the NHS research and development programme? British Medical Journal, 1995; 310 : 1318–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sachs M & Buchanan P. Breastfeeding and breast cancer: Research review. Midwives Journal, 1998; 10 : 306–309. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bradburn J. Developing clinical trial protocols: the use of patient focus groups. Psychology Oncology, 1995; 4 : 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Wide Web . http://soton.ac.uk/hta

- 11. Buggins E & Fletcher E. The Voices Project. Training and Support for Maternity Services User Representatives London: National Childbirth Trust, 1997.

- 12. Milne R, Donald A & Altman D. Piloting short workshops on the critical appraisal of reviews. Health Trends, 1995; 27 : 120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Milne R & Oliver S. Evidence‐based Consumer Health Information: developing teaching in critical appraisal skills. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 1996; 8 (5): 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Help Box database of consumer health information, maintained by the Winchester: Help for Health Trust.

- 15. Cheung‐Judge MY & Henley A. Equality in Action: Introducing Equal Opportunities in Voluntary Organisations London: NCVO Publications, 1994.

- 16. Oliver S, Milne R, Bradburn J, Buchanan P, Kerridge L, Walley T & Gabbay J. Consumers’ contributions to a needs‐led health research programme. in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]