Abstract

Objectives To describe the development of the Prioritisation Scoring Index (PSI) and its use in a prioritisation framework, providing examples where it has been used to prioritise between bids from different specialities and to assist in decision‐making regarding funding of service developments. To outline lessons learned for other health authorities when developing their own prioritisation methodologies.

Background The PSI was designed for prioritising: investments and dis‐investments; non‐recurring and recurring monies as well as differing specialities, care groups and types of intervention.

Methods The PSI consists of a ‘basket’ of utility criteria and takes account of the numbers of people that would receive the proposed intervention and the marginal cost for each additional person receiving the intervention. A multidisciplinary panel scored and ranked the bids. Two rankings were produced for each intervention according to (1) the average panel score for the utility criteria and (2) the cost per additional person receiving the intervention. An average of these two rankings produced the overall PSI rankings.

Results Almost 200 bids, with a total value of £50 million, were ranked, using the PSI, to prioritise developments worth approximately £17.5 million that could be funded in a phased implementation through the Health Improvement Programme.

Conclusions Use of the PSI has allowed explicit prioritisation of development bids in substantial exercises for both non‐recurring and recurring funding. We describe steps to be considered when other health authorities are developing their own prioritisation frameworks.

Keywords: cost‐effectiveness, decision‐making, methodology, prioritisation, resource allocation

Introduction

Recent literature has outlined the benefits of an explicit approach to establishing the principles for NHS priority setting. 1 , 2, –3 We developed the Prioritisation Scoring Index (PSI) as part of a prioritisation framework to prioritise between and within different clinical areas using the principles of cost effectiveness. Our methodology is transparent, simple to use and has been widely understood and accepted throughout Argyll and Clyde Health Board (ACHB) as the agreed mechanism for informing resource allocation decisions. We describe use of the PSI to prioritise bids against non‐recurring funding to address specific service pressures and in an exercise to inform the Health Improvement Programme. We also summarise the lessons we have learned.

Methods

Development of the PSI

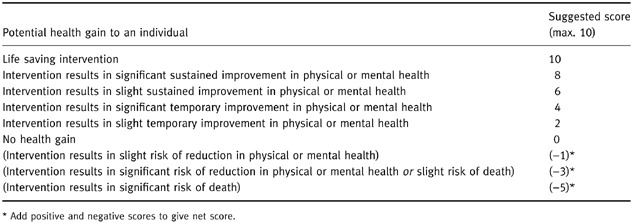

We identified examples of explicit priority setting methodologies that had been used in UK health authorities through literature review and by attending presentations from experts in this field. We examined five such examples: those from Birmingham, 4 Gwynedd, 5 City and Hackney, 6 Wandsworth, 6 and Wakefield. 7 All used explicit scoring and ranking mechanisms. Most allocated points according to weighted criteria and one used negative scores. In reviewing these examples, we found that no single mechanism was suitable for our purposes, although we selected criteria and attributes from these to form the basis of our own methodology. In adapting the basic methodology we sought opinions from a variety of groups, including public health, Local Health Council, NHS managers and clinicians, regarding the factors that are important in making priority decisions between different health interventions. The factors that these groups considered to be important were the ‘benefits’ (or utility), the numbers of people that would receive the intervention and the costs per additional person. Following piloting and amendment of a draft methodology, we included nine utility criteria in the PSI, weighted with maximum and minimum scores and some with negative scores. We devised detailed descriptors to exemplify the potential outcomes for each criterion from an intervention. Panel members used these descriptors to score the bids. An example is ‘potential health gain to an individual’ (Table 1).

Table 1.

Detailed descriptors used to allocate scores for potential health gain

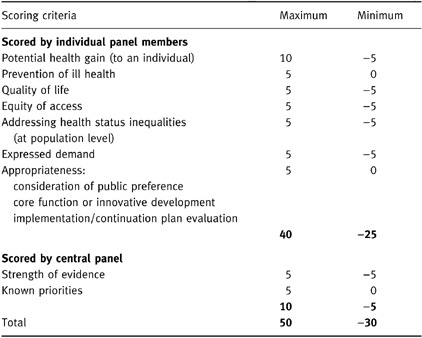

The nine utility criteria and the maximum and minimum scores are listed in Table 2. We scored the last two criteria ourselves based on validated information since we did not expect the scoring panel to have access to this information.

Table 2.

PSI scoring criteria and weights

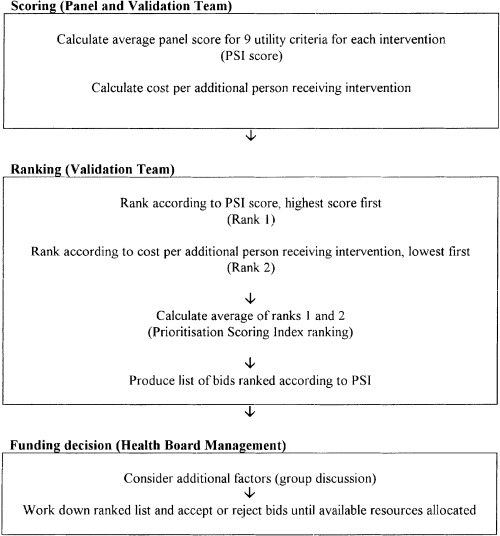

We designed an application form mirroring the PSI utility criteria and used a spreadsheet to capture information and to allow analysis. We computed the two rankings, and calculated the average, as shown in Fig. 1. We performed extensive piloting, covering a range of examples. This piloting included using the PSI ‘live’ to score and rank 68 projects submitted to the Primary Care Development Fund in 1997–98, with 46 of the projects funded from the allocated budget.

Figure 1.

Summary of PSI methodology.

Use of the PSI to rank bids for non‐recurring and recurring monies

Initial non‐recurring prioritisation exercise (1997)

When non‐recurring funding became available to ACHB for the specific categories: ‘winter peak’, waiting list and contract pressures we issued our trusts with the application forms to submit bids. We trained a scoring panel, including both managers and clinicians, in how to score and rank bids. We subsequently sent them the actual bids, the PSI criteria and a scoring sheet. We facilitated a meeting of the panel at which the scores of individual panel members for the nine utility criteria were averaged to obtain the panel average score. We then ranked the bids accordingly (Rank 1 in Fig. 1).

We validated the financial and other details on the bids and completed the steps outlined in Fig. 1. We produced the ranked list of bids and summary of relevant additional information and presented this to the Health Board’s General Manager’s Group. Using the ranked PSI list and considering important political and other factors, they agreed a proposed list of bids to be funded. Trust Chief Executives in ACHB concurred with the funding decisions.

Recurring prioritisation exercise (1998) to inform the 1999/2000–2003/4 Health Improvement Programme (HIP)

During 1998, Argyll and Clyde Health Board used a prioritisation exercise to inform the 1999/2000–2003/4 Health Improvement Programme (HIP). 8 Board‐wide steering groups, which reflect national NHS priorities such as cancer and mental health, and NHS trusts were asked to submit bids that would take forward their services strategically. A health board team validated these development bids and a large multidisciplinary panel then prioritised them. This panel included clinicians and managers from throughout the NHS in Argyll and Clyde and representatives from local authorities, voluntary organisations and the Local Health Council. As for the non‐recurring exercise, our General Manager’s Group considered the full ranked list of priorities and made funding decisions based on this list but also using their knowledge of strategic priorities and political issues. The results were then incorporated in the Strategic Financial Plan, which involved the phased release of money from efficiency savings and formed the basis of the Health Improvement Programme for 1999/2000–2003/4. In this way the PSI was used as a tool to assist management decision‐making.

Results

Use of the PSI to rank bids for non‐recurring monies

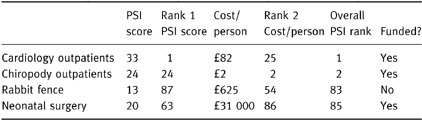

From the 92 bids received, with a total value of £4.6 million, funds were allocated to 52 bids. Examples from the top and bottom of the PSI ranked list are shown in Table 3 to illustrate the scoring and ranking methodology. Bids that received high rankings using the PSI were those that were allocated high scores by the panel for the utility criteria, those that had a low cost per person receiving the intervention, or a combination. The bids at the top of the table were mainly waiting list initiatives and included bids for cardiology, chiropody, dermatology, orthopaedics and physiotherapy. Only two bids in the top 10 were rejected for funding due to recurrent funding implications.

Table 3.

Examples from results for 94 non‐recurring bids for waiting list and winter peak monies

At the bottom of the PSI list of ranked bids were those that received low scores for the utility criteria from the panel and those that had very high costs per person receiving the intervention, or both. An example of this is a bid for an airstrip rabbit fence on one of our sparsely populated islands, which received a very low priority and was not funded from this allocation. In contrast, some bids were funded despite their low rankings due to additional factors that had to be considered. For example, a bid received for neonatal surgery was at the bottom of the rankings because of its relatively low score and high cost per baby receiving surgery. Despite this, the bid was funded because of the ethical and political implications of not doing so.

Results of the 1998 HIP prioritisation exercise

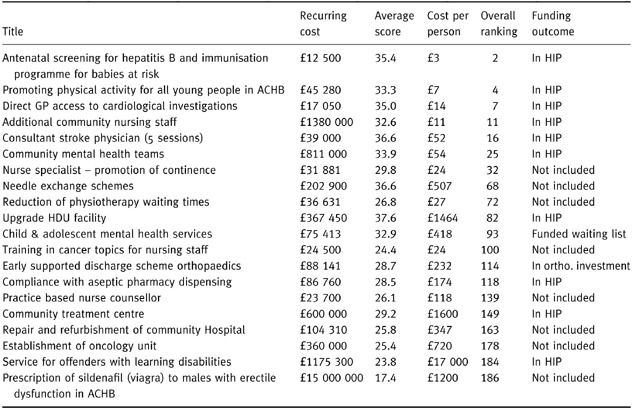

From almost 200 development bids received, with a total value of approximately £50 m, approximately £17.5 m was allocated to specific phased developments. The results of this prioritisation exercise form the basis of the Argyll and Clyde Health Board Health Improvement Programme for 1999/2000–2003/4. Extracts from the top, middle and bottom of the ranked list are shown in Table 4 to illustrate how the PSI results were used as an aid to management decision‐making in helping determine priorities for inclusion in the HIP.

Table 4.

Results of the 1998 HIP prioritisation exercise: extracts from top, middle and bottom of the ranked list

Discussion

The need to prioritise the distribution of scarce health‐care resources against the increasing demands on these resources has been widely discussed. 1 , 2, –3 We have recognized the need to develop an explicit mechanism locally, whereby differing health‐care interventions, ranging from health promotion activities to tertiary prevention and rehabilitation, can be prioritised in a relevant, understandable, repeatable, robust, transparent and standardized way. Our PSI methodology acts as a tool to inform management decision‐making. Health board managers identify strategic local and national priorities and ‘must‐do’s’ of legal and political importance as being relevant considerations in addition to the PSI ranked priorities. 9 For example, managers, using their judgement of the ethical, legal and political implications, made the decision to fund neonatal surgery in preference to some other interventions that received higher PSI rankings. Managers felt that a prioritisation methodology, no matter how robust, does not provide evidence strong enough to make a decision to refuse life‐saving surgery to small babies. In addition, this highly emotive topic would attract strong public support and possible legal action.

Our methodology allows prioritisation across health programmes as well as within them. In contrast, programme budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA) 10 techniques work best in prioritising within service programmes and do not tend to be successful in transferring resources between one service and another. The advantage of our method is that we can assess and compare the relative priorities of interventions in different service areas using identical criteria and methodology. The PSI method of prioritising between different health interventions is also more practical than quality adjusted life years (QALYs), 11 which would require a great deal more time and effort to assign benefit scores to each intervention. We acknowledge that our methodology does not produce output that can determine the desirable ‘cost per quality adjusted life year’ (QALY) which can produce league tables of interventions in terms of this standard measure. It does, however, incorporate both utility and cost in its ranking methodology and takes account of both the length and quality of life, thereby acknowledging that survival may not always be the best outcome.

To date, explicit decisions about rationing core activities have not had to take place in ACHB. We know that in some health authorities in the UK rationing decisions about certain plastic procedures and treatments such as infertility services have resulted in explicit rationing policies. 2 , –3 During piloting we validated the PSI by confirming that the PSI utility scores for interventions known to be of low health gain were minimal and, although we have not yet applied the PSI to potential dis‐investments, this is a possible future use of the methodology.

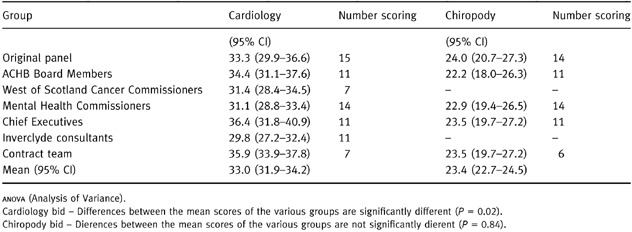

We have presented our methodology to several clinical and managerial groups. These groups each scored the same two bids for cardiology and chiropody interventions, previously scored and ranked by the original panel. The results of these scoring exercises were used to test the variability of scoring between different groups, using confidence intervals and analysis of variance. These results are shown in Table 5. Although the numbers are small, these statistics suggest that the methodology is robust enough to produce consistent, but not exactly replicable, results. All assessors have been able to complete the PSI on each occasion although the participants in the scoring have included a wide range of health‐care professionals and others.

Table 5.

Variability of scoring between groups

It has been possible to bank the results from non‐successful bids so that they can be reconsidered in subsequent prioritisation exercises. This banking process could also lead to the future possibility of pooling prioritisation results across health authorities to share workload.

There has been ‘process utility’ involved in the scoring and the pooling of results across a wide range of health‐care professionals in terms of discussion and gaining a wider perspective of the workload of other professionals. This has resulted not only in there being very few arguments as to how the resources were distributed but also in an enthusiasm for continuing to use the PSI. 9

We recognize that there are still some weaknesses within the process. Part of the ranking has relied on information being received from service providers as to the marginal cost per patient receiving the intervention. There is, in some instances, a wide confidence interval around these numbers. The weightings of different criteria within the PSI were developed subjectively and we have further work to do in validating these. For example, the PSI gives higher weighting to length rather than quality of life and the overall ranking is calculated in a way that gives equal weighting to utility and cost. We have recently completed a large survey of the values of our general public and medical practitioners to reassess the criteria and weightings. This survey asked a wide audience to indicate, using likert scales, their preferred weightings for prioritisation criteria. We plan to perform a similar survey to obtain the views of health and local authority managers and politicians. We will also perform sensitivity analysis to assess the extent to which previous prioritisation exercise results would differ using the preferred weightings of these groups compared to the current PSI weightings.

The PSI has been externally evaluated using semi‐structured interview of key players. 9 This evaluation identified a general understanding of the PSI as a useful tool that supports management decision‐making. It also highlighted specific areas where there is room for improvement to both the methodology and its application.

We will consider all of these points in a revised PSI.

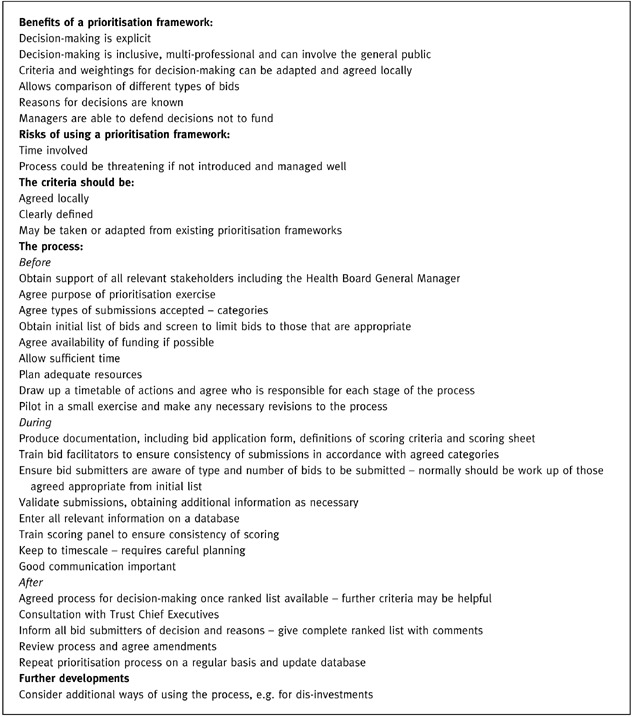

To date the PSI has proved extremely useful, robust, transparent and acceptable for its use in allocation of non‐recurring and recurring development funding. We participated in a national working group that considered the possibility of producing a single prioritisation methodology for use in all Scottish health boards. This group concluded that each board should develop its own framework, guided by the experience from existing prioritisation methodologies. 12 We have used our methodology now on several occasions and have, therefore, summarized the main points that we have learned from our experience. These observations may be helpful to any health authority embarking on a similar prioritisation exercise (Box 1).

Table Box 1 .

Factors to consider when developing a prioritisation framework

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who participated in the development and use of the Prioritisation Scoring Index. In particular, we acknowledge the input of Nicholas Scott (Public Health Researcher) who performed the statistical analysis.

Bibliography

- 1. New B. The rationing agenda in the NHS. British Medical Journal, 1996; 312 : 1593–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Working Party on Priority Setting Priority setting in the NHS First report of a working party, 1996.

- 3. Rationing in Action BMJ Publishing, 1993.

- 4. Ham C. Priority setting in the NHS. British Journal of Health Care Management, 1995; 1 (1): 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 5. House of Commons Priority setting in the NHS . Purchasing Health Committee First Report: 1, 1995.

- 6. Ham C. Priority setting in the NHS. Reports from six districts. British Medical Journal, 1993; 307 : 435–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Watson P. Knowing the score Health Service Journal.: 14 March 28–31, 1996. [PubMed]

- 8. Argyll and Clyde Health Board Health Improvement Programme, 1999/2000–2003/4 Argyll and Clyde Health Board 1999.

- 9. Thompson D. Argyll and Clyde Health Board Prioritisation Scoring Index. An evaluation Health Services Management Centre University of Birmingham Report, 1999.

- 10. Madden L, Hussey R, Mooney G & Church E. Public health and economics in tandem: programme budgeting, marginal analysis and priority setting in practice. Health Policy, 1995; 33 : 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robinson R. Cost‐utility analysis. British Medical Journal, 1993; 307 : 859–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Public Health Medicine Working Group Looking at Prioritisation Frameworks for use in Health Boards Report to the Directors of Public Health Medicine Group, 1999.