Abstract

For many years, public information about screening has been aimed at achieving high uptake but concerns are now being raised about this approach. There are several problems that have prompted these concerns. By giving information that emphasizes only the positive aspects of screening the autonomy of individuals is ignored, individuals feel angry when they perceive that they are let down by screening, symptoms may be disregarded because of the belief that screening gives full protection, health service staff carry the blame for problems that are in fact inherent in screening, and sound debate about policy and investment in screening is hampered by misunderstanding about the benefits and costs of screening.

If we adopt instead an approach that makes explicit the limitations and adverse effects then a different set of problems will be encountered. We risk a reduction in uptake of screening and thus population benefits may reduce, those most likely to be deterred from accepting screening may be the most socially disadvantaged, there will be a cost in terms of staff time to explain screening more fully to participants, and cost‐effectiveness could be reduced if uptake falls so low as to make services barely viable.

In the UK current General Medical Council (GMC) advice 1 to doctors about informed consent for screening makes it clear that full information should be given. The UK National Screening Committee has also signalled the need for a changed approach to information 2 giving so that individuals are offered a choice based on appreciation of risks and benefits. It will take time for this approach to be fully reflected across the full range of UK screening programmes. New national information will be needed to assist staff in giving full information, and some aspects of policy, such as screening coverage targets for Health Authorities and General Practitioners, will need to be altered.

There are many questions still to be answered about the kind of information needed to achieve informed participation, and about how it should be framed and communicated. These questions can begin to be addressed when there is clarity at national level about the purpose of information about screening.

Keywords: autonomy, ethics, informed choice, population uptake, screening

Introduction

In recent years questions have been raised in England and Wales about whether the traditional approach to information giving for participants in screening is really appropriate. 3 , 4 The debate so far has been low profile and shared mainly amongst professionals working in the NHS delivering cancer screening, genetic screening and antenatal screening for fetal abnormality. With the publication of the Second Report of the UK National Screening Committee 2 this debate will need to widen. Our past approach to information giving has stressed the population benefits of screening with the aim of encouraging everybody eligible to participate. The National Screening Committee now advises that the limitations of screening and any potential adverse effects for the individual or their wider family should be made explicit to potential participants from the outset. In some specific areas, such as antenatal testing for Downs syndrome 5 and predictive testing for Huntington’s disease, 6 the need for honest pretest information giving is already well recognized. The notion of insisting upon 90% uptake for these tests would now seem strange. For the two existing UK cancer screening programmes pretest information is still fairly limited. Examples of the limitations one might need to explain would be the fact that not every case of cervical cancer or death from breast cancer can be prevented in screened subjects. An example of an adverse effect would be that for the majority of subjects undergoing investigation and treatment their condition would not have progressed to serious disease during their lifetime.

This possibility of explicitly spelling out the less positive aspects of screening, in terms that can be readily understood by potential participants, raises several questions. It raises questions about the purpose of screening in terms of public health gain and about the ethical principle of individual autonomy. It raises issues about disadvantaged groups and whether their take up of screening would be jeopardized. In addition it raises practical issues concerned with conveying complex information, as well as some basic difficulties in actually establishing what are the full and true facts about all potential consequences of any screening pathway. Within the cervical screening programme these issues have been hotly debated, and the following section draws upon this experience.

How has the debate about informed consent progressed within the NHS Cervical Screening Programme?

Cervical screening in the UK has been characterized by optimism in the 1960s, then disillusionment in the 1970s, followed by tremendous achievements in organization during the 1980s. England, Scotland and Wales now each has a nationally led programme with published quality standards and quality assurance processes. This organization and quality assurance has delivered uniformly high quality screening to over 80% of the eligible female population aged 25–64. This has been accompanied by a downturn in age specific mortality rates in each of the birth cohorts born since the 1930s 7 In the absence of randomized controlled trial evidence, the potential incidence reduction achievable by screening has been estimated by case‐control comparisons and modelling. 8 Simple messages to the public such as ‘cervical cancer is preventable’ have however, generated the expectation that every case is preventable if screening is done ‘properly’. Now that poor organization can no longer be blamed there is growing realization that cervix cancer cases, and deaths, do still occur despite good screening, and that high rates of screen detected abnormality are a universal and continuing phenomenon. 9 There is still however, a long way to go in achieving widespread public understanding of these inherent limitations. To most people a case of cervical cancer in a screened individual must mean a ‘blunder’, 10 and to most women an abnormal smear result provokes immediate and real fear of cancer. 11

Concerns about public information giving began to be raised in the literature and at conferences during the 1990s. In 1997 a Workshop at the Manchester Business School 12 involved lawyers, an ethicist, a consumer representative, and professionals involved in cervical screening. The group was completely split when asked to give a straight yes or no answer to the question ‘should women be given information about the consequences of screening if this might deter them from taking up the offer of the test?’ The crux of the disagreement centred on the issue of individual autonomy vs public good. Some argued that women would be tempted to make the ‘wrong’ decision for their health if they knew that they might, for example, undergo unnecessary hospital investigation. Others argued that autonomous adults have the right to make their own choices about things that affect their lives, and that no‐one can judge what is the ‘right’ decision for another individual.

In 1997 a report was published 13 following a review of the Kent and Canterbury laboratories, where problems had been identified with smear reporting and staff training. As a main recommendation this report included: ‘There should be better information nationally about the benefits and limitations of the screening test as well as a national publicity strategy to improve understanding of the screening programme’. In 1998 the second UK National Cervical Screening Conference held in York included a Citizen’s Deliberation where a panel of ordinary women heard evidence from witnesses to address the question ‘should women have faith in the cervical screening programme?’. The panel concluded that they should have confidence in the programme but rejected the word faith, and they asked that more information about the difficulties of delivering the service and about the limitations of cervical screening, should be available to women. Their judgement was that information about limitations would actually enhance public confidence because expectations would become reasonable and realistic. Later that year a published ‘open letter’ to Health Ministers 14 asked for ‘open and frank honesty with regard to inherent acceptable errors within the NHS cervical screening programme’.

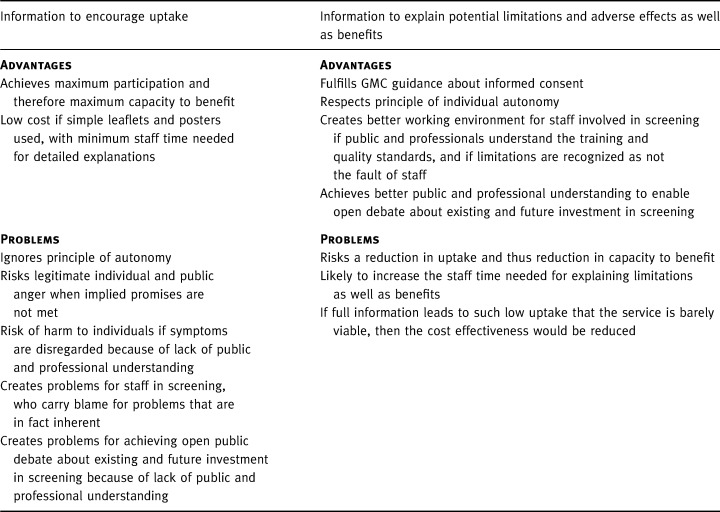

Guidance for doctors in the UK from its professional regulatory body, the GMC, 1 reflects current thinking for many, and is influenced by the experience of hearing complaints from service users about the medical profession. It is clear and detailed: ‘You must respect patients’ autonomy…their right to decide whether or not to undergo any medical intervention, even where a refusal may result in harm to themselves’. The GMC warns against assuming that apparent compliance constitutes informed consent. Specifically relating to screening, the advice states ‘you must ensure that anyone considering whether to consent to screening can make a proper informed decision…. You should be careful to explain clearly the purpose of the screening; the likelihood of positive/negative findings and possibility of false‐positive/false‐negative results; the uncertainties and risks attached to the screening process and any significant medical, social or financial implications’. Despite this, policy for the National Health Service Cervical Screening Programme (NHSCSP) has been strongly governed by coverage targets for Health Authorities and by payments for General Practitioners that depend upon 80% uptake in their patients eligible for screening. Both act as a deterrent to giving more balanced information. As Anderson and Austoker 3 , 4 have both commented, if informed choice for participants is to become a reality then there is a lot of unlearning to be done even amongst professionals. The main considerations that have been raised as part of this debate are summarized Table 1.

Table 1.

The advantages and problems of giving promotional information vs giving full information about harm and benefit

Do practical difficulties affect the principle of giving negative as well as positive information?

When discussing the giving of information about screening one soon encounters practical difficulties concerned with assembling accurate quantitative estimates for the risk of different possible outcomes. Interpretation of available research data is difficult. Trials of screening tend to be less well controlled than trials of treatment. This leaves uncertainty about results because of potential for bias. What therefore should we tell people? Does routine three yearly mammography cut breast cancer deaths by 30%, or is it far less? Should you frame the information in absolute terms? That is, for 1000 women screened for 10 years one will have their life saved and 490 will have had a false alarm. Should you frame it in relative terms to make it sound more positive? How can we be certain what the mortality trends for cervical cancer would have been in the absence of screening? There is no doubt that agreement amongst acknowledged screening experts over precise numerical values for benefits and adverse effects could not be achieved.

Faced with this difficulty one has to return to the principle of what the information is for. If participants need to understand that screening may lead to investigation and treatment for a condition that would never have caused a problem, then this can be communicated. It does not require an accurate quantitative estimate of likelihood in order to convey this fact. Much of the debate about what is accurate information stems from concerns about whether adverse effects of screening should be publicly acknowledged. This reluctance itself stems from the wish not to undermine screening uptake. The present arguments about truth are in themselves a consequence of the lack of clarity about the purpose of information for participants. One frequently encounters the argument: ‘you must not say that because it could put people off’ rather than ‘you must not say that because it is not true’. There are many truths and much uncertainty. Agreement about truth of information can only be achieved once we are clear about the purpose of the information.

What are the public health aims of screening?

The reasons for regarding early disease detection as a public health programme with public health aims can be broadly summarized as follows:

1. Organization. Experience (for example with phenylketonuria (PKU) screening of newborns, cervical screening) has shown that the most beneficial and fair way of delivering screening is through nationally co‐ordinated programmes with uniform policy, training, and quality assurance.

2. Evidence‐based policy. Screening programmes bring a variety of benefits and harms for different individuals and for society as a whole. For this reason, the decision of whether or not to offer any given screening activity within the NHS is best taken nationally, informed by best available evidence as to the overall effects for the public’s health. Individuals within society separately experience the benefits and the harms.

3. Achievement of cost‐effectiveness. Screening programmes introduced in a planned way according to national policy can achieve greatest efficiency. This relates partly to the targeting and frequency of screening, for example three yearly mammography for age 50–64. It relates partly to deployment of equipment and resources. For example, breast screening units in the UK were planned nationally by population size and access considerations in order to avoid haphazard development with duplication of facilities and higher cost.

4. Ensuring access for all. Organized programmes that systematically invite all eligible individuals have been seen as an important means of ensuring equity, since without a systematic approach then highest risk individuals tend to be least well represented amongst those attending for screening. If information about screening is now to spell out limitations and adverse effects then there is a theoretical worry that this could compound inequalities in health. The highest risk hardest to reach groups may be the most easily deterred. There is no evidence for this and it may be that accessibility, acceptability, and personal invitation are more important factors. It can be postulated that better educated groups may be most likely to decline screening as they may be more likely to explore the information fully.

Information for the public and the achievement of public health aims are inextricably linked. Co‐ordinated national programmes lend themselves to the giving of uniform public information. Benefits have been explained in national terms –‘cervical screening is preventing 1300 deaths annually’– rather than as benefits to an individual. Uptake has tended to be seen as a sole marker of success as though herd immunity applied and screening would have no benefit unless a target uptake is reached. This approach is continuing as evidenced by the way that universal antenatal HIV screening is being introduced in the UK. Uptake targets have been set, and the written information for women includes no explanation of false positive tests.

Public acceptance of efficiency measures has succeeded up to now because it is seen as nationally ‘fair’, although the economic justification for age group targeting or choice of screening method has not been made explicit to individuals. Information giving is approached with the population as a whole being seen as the recipient of the service. The need for each individual to understand the reasoning behind policy decisions that affect them, or the benefits and adverse consequences that they may face, has not been seen as a main issue.

Do requirements for individual informed choice conflict with public health goals?

Providers of screening services in the UK receive frequent queries from health‐care consumers about screening policy. For example, ‘why can I not have more frequent screening? why stop at 64? why don’t you screen everyone as soon as they reach 50?’ The public has assumed that if screening ceases at 64 this is because women over 64 have a low risk of breast cancer. 15 Considerations of efficiency in the overall use of society’s resources, however legitimate, have not been part of the information giving about screening. Because the public believe screening to be a highly powerful and inexpensive means of preventing ill health there is understandable indignation when they learn that policy has been influenced by consideration of costs.

Recent examples both within and outwith screening give an indication of potential and actual damage to individuals and to the viability of screening if we continue with the current approach to information giving. Hazel Thornton 16 has argued from a consumer viewpoint that information about breast screening is wholly inadequate, leaving women feeling ‘angry and duped’ when they discover that uncertain categories of disease can be uncovered, and that absolute chance of benefit for each individual is small. Ruth Lea of the Institute of Directors 17 recently criticized the cervical screening programme for disregarding individual autonomy and misleading women about their chance of developing cervical cancer. Sarah Harman, 18 a barrister, stated that ‘women should have more information about the limitations of the smear test. Many of my clients were let down by their own lack of knowledge and that of their General Practitioners who disregarded symptoms and relied on smear results.’ A national cancer charity, Colon Cancer Concern, participated with the National Screening Committee’s work in establishing bowel cancer screening pilots, and argued that information about the potential adverse consequences of bowel cancer screening must be made explicit even if this might deter people from accepting an offer of screening. Recent legal cases have related to cancers occurring despite screening, and to the birth of a Downs syndrome baby to a screened mother.

Beyond the field of screening there are examples indicating that public expectations for full information are not matched by professional recognition of these expectations. A GMC inquiry into paediatric cardiac surgery in Bristol, following exposure of high postoperative mortality rates, criticized the surgeons’ conduct in failing to explain the risks of surgery adequately to parents. There has been public dismay in learning of routine post mortem organ removal without explicit consent from relatives. 19 An inquiry in Stafford relating to research in paediatric intensive care 20 has shown a disparity between what doctors felt they needed to tell parents, and what parents believe they ought to have been told.

Overall this points to the need to include more than just coverage rates and lives saved into the public health equation. Harm to uninformed participants leads to anger, bitterness, and potentially to litigation. Individual’s stories are interpreted as ‘scandals’ if there is no bedrock of public understanding of the context in which screening is carried out. This lack of understanding means that every public criticism of screening has to be countered with ever more positive assertions in order that public confidence is not shaken. It is inappropriate to continue to use information about screening purely for encouraging high uptake. Uptake in disadvantaged groups can be addressed by making services accessible, rather than by selective use of information. Participants in screening are autonomous consumers of health‐care who should have access to information to enable informed choice about whether or not to participate.

References

- 1. Seeking Patients’ Consent: the Ethical Considerations . London: General Medical Council, November, 1998.

- 2. Second Report of the UK National Screening Committee . www.nsc.nhs.uk. Departments of Health for England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales, October, 2000.

- 3. Anderson CM & Nottingham J. Bridging the knowledge gap and communicating uncertainties for informed consent in cervical cytology screening; we need unbiased information and a culture of change. Cytopathology, 1999; 10 : 221–228.DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.1999.00198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Austoker J. Gaining informed consent for screening. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319 : 722–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith DK, Shaw RW, Marteau TM. Informed consent to undergo serum screening for Down’s syndrome; the gap between policy and practice. British Medical Journal, 1994; 309 : 776–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hayden MR. Predictive testing for Huntington’s disease: the calm after the storm. Lancet, 2000; 356 : 1944–1944.DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03301-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sasieni PD, Cuzick J, Farmery E. Accelerated decline in cervical cancer mortality in England and Wales. Lancet, 1995; 346 : 1566–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. IARC . Working Group on Evaluation of Cervical Cancer Screening Programmes. Screening for squamous cervical cancer: duration of low risk after negative results of cervical cytology and its implication for screening policies. British Medical Journal, 1986; 293 : 659–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raffle AE, Alden B, Mackenzie EFD. Detection rates for abnormal cervical smears: what are we screening for? Lancet, 1995; 345 : 1469–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elliott J. Rachael Lewis, a mum of two, had a cervical scan last May. Bristol Evening Post, November 11, 1997; 1.

- 11. Chesworth N. My ordeal after cancer test blunders. Daily Express, June, 10, 1995; 9.

- 12. Anderson CM. Lawyers, Ethicists and Consumers want Greater Honesty about Cervical Screening Report to the NHSCSP and the National Screening Committee. Manchester: Multi‐disciplinary Workshop, Manchester Business School, 12, March, 1997.

- 13. Wells W. Review of cervical screening services at Kent and Canterbury Hospitals NHS Trust London: NHS Executive South Thames, October, 1997.

- 14. Slater DN. Open and frank honesty with regard to inherent acceptable errors within the NHS cervical screening programme. (open letter to Baroness Jay, Rt Hon Frank Dobson, and others.). Association of Clinical Pathologists News, 1998; Autumn: 70–72.

- 15. Horton Taylor D, McPherson K, Parbhoo S, Perry N. Response of Women age 65–74 to invitation for screening for breast cancer by mammography. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 1996; 50 : 77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thornton H. The voice of the breast cancer patient – a lonely cry in the wilderness. European Journal of Cancer, 1997; 33 : 825–828.DOI: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00487-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lea R. Healthcare in the UK. The need for reform. London: Institute of Directors, 2000.

- 18. Harman S. Cervical Screening (Letter). Lancet, 2000; 355 : 410–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dyer C. Government orders inquiry into removal of children’s organs. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319 : 1518–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. West Midlands Regional Office Report of a Review of the Research Framework in North Staffordshire NHS Trust . West Midlands: NHS. Executive, May, 2000.