Abstract

Objective To report data relating to the informed uptake of screening tests.

Search strategy Electronic databases, bibliographies and experts were used to identify relevant published and unpublished studies up until August 2000.

Inclusion criteria RCTs, quasi‐RCTs and controlled trials of interventions aimed at increasing the informed uptake of screening. All participants were eligible as defined by the entry criteria of individual programmes. Studies had to report actual uptake and meet three out of four criteria used to define informed uptake.

Data extraction and synthesis Relevant studies were identified, data extracted and their validity assessed by two reviewers independently. Outcome data included screening uptake, knowledge, informed decision‐making and attitudes to screening. A random‐effects model was used to calculate individual relative risks and 95% confidence intervals.

Main results Six controlled trials (five RCTs and one quasi‐RCT), focusing on antenatal and prostate specific antigen screening, were included. All reported risks/benefits of screening and assessed knowledge. Two also assessed decision‐making. Two reported risks/benefits to all randomized groups and evaluated different ways of presenting information. Neither found that interventions such as videos, information leaflets with decision trees, or touch screen computers conveyed any additional benefits over well‐prepared leaflets.

Conclusions There is some evidence to suggest that changing the format of informed choice interventions in screening does not alter knowledge, satisfaction or decisions about screening. It is not clear whether informed choice in screening affects uptake. More well‐designed RCTs are required and further research should also be directed towards the development of a valid instrument for measuring all components of informed choice in screening.

Keywords: informed uptake, screening, systematic review

Background

Screening has been defined as ‘the systematic application of a test or inquiry, to identify individuals at sufficient risk of a specific disorder to warrant further investigation or direct preventive action, among persons who have not sought medical attention on account of symptoms of that disorder’. 1 By detecting disease before symptoms occur screening programmes can be an effective method of reducing morbidity and mortality. Screening can be carried out with the aim of primary prevention (e.g. screening for risk factors such as hypertension), secondary prevention (e.g. cancer screening) or tertiary prevention (e.g. screening for sensorineural deafness).

High rates of uptake need to be attained if screening programmes are to have a significant population impact in reducing mortality and/or morbidity from a disease or condition. However, there have been many debates in recent years about the desirability of attaining high rates of uptake of screening per se, without allowing participants to make an informed choice or decision about whether to be screened. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Consequently, tensions arise between promoting informed choice, where the individual may choose not to undertake screening, and promoting effective forms of health‐care such as screening.

An informed decision can be described as one where, ‘a reasoned choice is made by a reasonable individual using relevant information about the advantages and disadvantages of all the possible courses of action, in accord with the individual’s beliefs’. 6 It has been argued that in order to make an informed decision about whether to participate in screening, an explicit sharing of information about the risks and benefits is required. 7 This is likely to become more visible in the UK with the recent guidance issued by The General Medical Council. 8 The guidance states that: ‘Doctors should give information on the following: the purpose of the screening; the likelihood of positive and negative findings and possibility of false positive/negative results; the uncertainties and risks attached to the screening process; any significant medical, social or financial implications of screening for the particular condition or predisposition; and follow‐up plans, including the availability of counselling and support services’. In contrast in the United States of America (USA) certain states legally enforce compulsory screening practices such as those for neonatal screening. 9

An HTA report has recently been published which assesses the literature on the determinants of screening and on interventions to increase uptake. 10 The original brief of the HTA report was to look at actual uptake (see HTA report for results relating to uptake), as issues surrounding informed uptake and choice had not been raised at the time. However, data on informed uptake were also collected where available. The purpose of this paper is to report on the data relating to informed uptake, and to discuss some of the issues surrounding informed choice in screening.

Methods

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed and is described in detail in the original HTA report. 10 Twenty‐three electronic databases were searched in the original report (see Appendix 1) and an updated search was undertaken to identify any relevant trials published from 1998 to August 2000. Additional references were located through searching the bibliographies of identified studies and related papers and by contacting specialists in the subject area of the review. There were no language restrictions, and both published and unpublished studies were included if they met the inclusion criteria.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Inclusion criteria

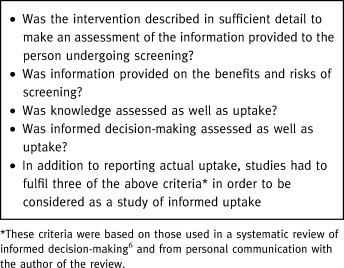

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs (e.g. using pseudo‐randomization, such as alternation or date of birth), and controlled trials (non‐randomized cohort with concurrent control) of interventions that aimed to increase the informed uptake of screening. All screening programmes (universal, selective or opportunistic) that aimed to identify the presence or absence of a specific condition, disease or disability during the pre‐symptomatic phase or before clinical detection (including antenatal screening of parents) were included. Participants were those eligible to take part in a screening programme as defined by the entry criteria for that programme. All studies had to report a measure of actual uptake either as recorded by health service records (such as a screening administration system, hospital or GP records) or by patient self‐report (such as via telephone interview or questionnaire). In addition four criteria (see Box 1) were used to determine whether the intervention was aimed at informing uptake, rather than just increasing uptake. Studies had to meet three or more of these criteria in order to be included. These criteria were adapted from an earlier review of informed decision‐making and from personal contact with the author. 6

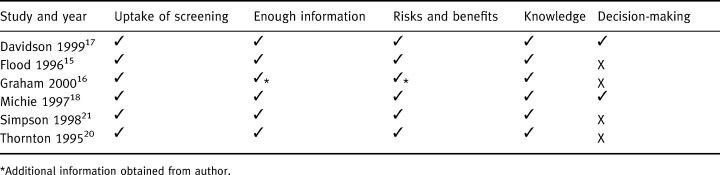

Table 1.

Box 1 Criteria for informed uptake

Exclusion criteria

Studies of self‐examination procedures, such as breast self‐examination and testicular self‐examination, and studies that only reported intermediate measures of screening uptake, such as the booking of appointments, intentions to uptake screening, or attitudes to and knowledge of screening, were excluded.

Data extraction and assessment of study validity

One reviewer screened the titles and abstracts of 46 000 studies and a second reviewer checked a random sample (5%) of included and excluded papers. Full paper copies of 451 studies were independently assessed for relevance by two reviewers. Data were then extracted from relevant studies by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Disagreements at any stage were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. Outcome data were collected on the uptake of screening, knowledge of screening, informed decision‐making and attitudes to screening. Authors were contacted as required for additional data. Information was also recorded for each study with respect to seven items of methodological quality. Validity checklists in CRD Report Number 4 11 were modified and each item was graded as adequate (+), unknown, unclear or partial (+/–), or inadequate (–). The quality criteria were not used to obtain an overall quality score. Instead, the information was compiled into a table (see Table 1) and the results reported descriptively in the text.

Table 1.

Criteria for inclusion in the review

Data synthesis

Relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for the uptake of screening if data were available. RRs were calculated instead of odds ratios (ORs) for two main reasons. Firstly, whilst the OR and the RR are similar if the outcome is relatively rare (e.g. death), they are very different if the outcome is common, as in uptake of screening. This is because the control group’s risk affects the numerical value of the OR. Thus using an OR when the outcome rate is high (and especially if the baseline rate is high) will overestimate both the likely benefits and harms of treatment. 12 Furthermore, ORs are hard to interpret, and are often misinterpreted as RR. 13 Data on uptake were entered into the RevMan 4.0 software 14 and a random‐effects model was used. A test for heterogeneity was performed for all sets of comparisons and there was significant statistical heterogeneity for all comparisons. Thus the results were not pooled, but reported narratively in the text. Data on the other outcomes such as knowledge, anxiety, satisfaction, and decision‐making, were as reported in the individual papers.

Results

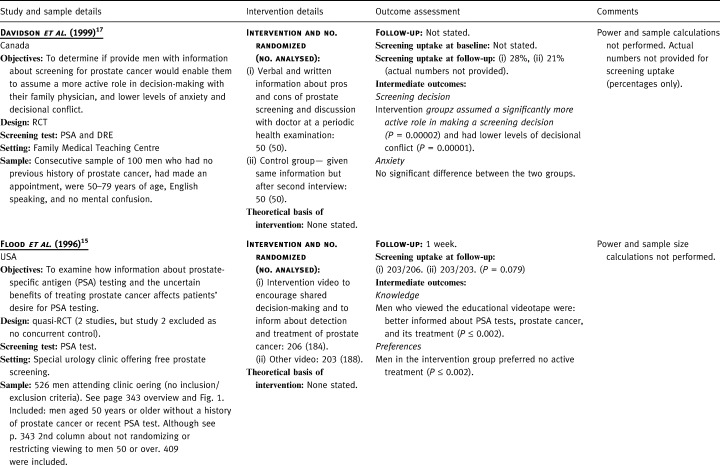

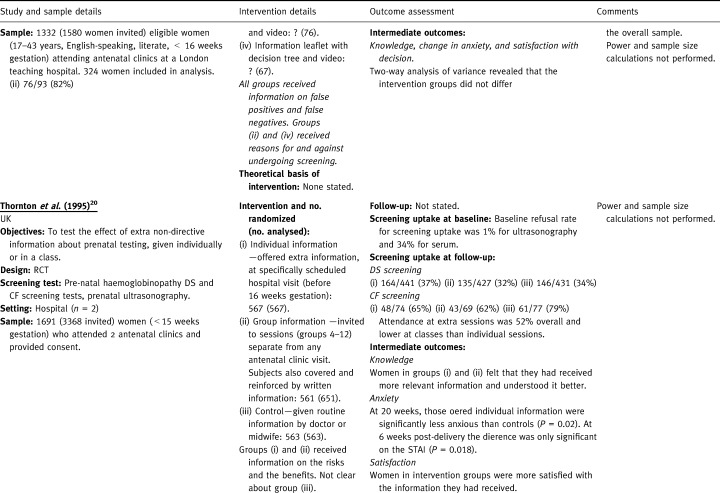

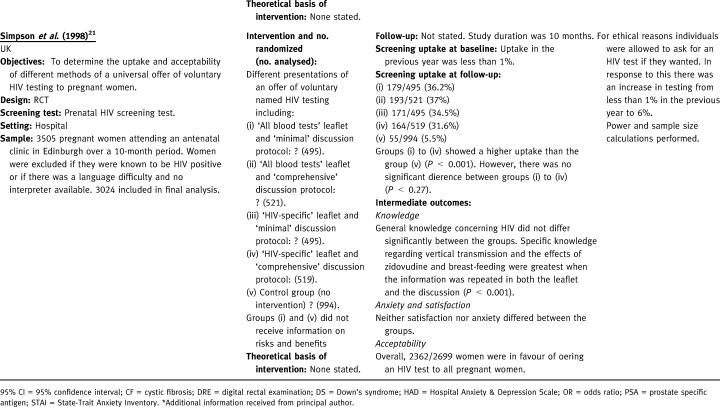

Six studies relating to the informed uptake of screening were included. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , Table 1 details the inclusion criteria fulfilled by each study. All studies reported giving information on the risks and benefits of screening, and assessed knowledge in addition to uptake. Two studies assessed decision‐making and thus met all of the four inclusion criteria. 17 , 18 Four focused on antenatal screening and were all undertaken in the UK between 1995 and 2000. Two further studies focusing on screening for prostate cancer were undertaken in the USA or Canada in 1996 and 1999.2, 2, 2, 2 gives more details of included studies.

Table 2.

Detail of included studies

Table 2.

(Continued)

Table 2.

(Continued)

Table 2.

(Continued)

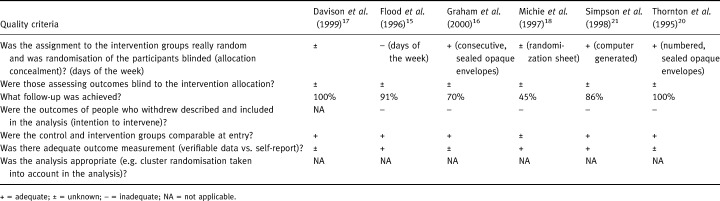

Quality of the included studies

The quality of the included studies was reasonable (see Table 3). Five of the six studies were RCTs and one was a quasi‐RCT. Of the RCTs, four described the method of randomization, with three reporting adequate allocation concealment. Blinding of assessors to the intervention was not mentioned in any of the studies. Follow‐up ranged from 45%–100%, and none of those with losses to follow‐up used an intention to intervene approach in their analysis. With regard to baseline characteristics, five reported no significant differences and one did not provide any data. Three used an adequate measurement to assess screening uptake, and three did not report on how it was assessed.

Table 3.

Quality of included studies

Interventions evaluated in the studies

Prostate cancer screening

One RCT gave verbal and written information about the ‘pros and cons’ of prostate screening prior to a periodic health examination. 17 Participants were encouraged to discuss this information with their doctor and to participate in making a screening decision to the extent that they were comfortable. The control group received information about general medical issues prior to the periodic health examination. Following a second interview after the medical appointment, men in the control group were provided with the same information as men in the intervention group. The other study (a quasi‐RCT) showed videos to men in a urology clinic, which was offering free prostate screening during a Prostate Awareness Week. 15 The intervention group was shown a video designed to encourage patients to participate in the decision to screen, which emphasized uncertainties surrounding the effectiveness of treatment. The control video emphasized only the benefits of prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening.

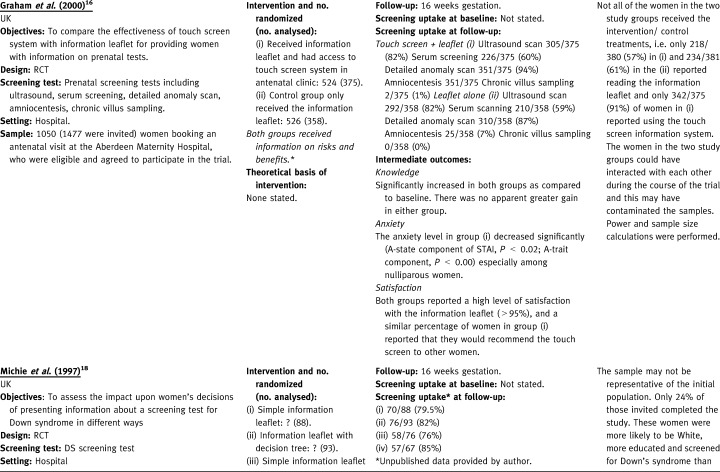

Antenatal screening

Two studies gave information on both the risks and benefits to all of the randomized groups and evaluated different ways of presenting this information. 16 , 18 The first evaluated leaflets (either simple or expanded plus a decision tree) with or without the addition of a 12‐minute video. 18 The second compared access to a touch screen information system in an antenatal clinic (plus a leaflet) with a leaflet only. 16 The other two studies had a control group and/or an intervention group, which did not receive information on risks and benefits. 20 , 21 One of these compared the effectiveness of offering prenatal testing information (either in an individual session or a group session) with a control group that received routine care. 20 The other evaluated four combinations of written and verbal communication (one did not receive information on risks and benefits) followed by the direct offer of a test. 21 The control group received no information and no direct offer of a test, although testing was available on request.

Results from individual studies

Prostate cancer screening

In the RCT of information‐giving prior to a medical appointment, 28% of the intervention group and 21% of the control group were screened with both a digital rectal examination (DRE) and a PSA test (actual numbers not provided). The intervention group assumed a significantly more active role in making a screening decision (P=0.00002) and had lower levels of decisional conflict (P=0.00001). There were no statistically significant differences in anxiety levels between the two groups. In the quasi‐RCT of educational videos, men viewing the educational video were less likely than the control group to have a PSA test but this was not significant (P=0.079). 15 Furthermore, men who viewed the educational videotape were better informed about PSA tests, prostate cancer and its treatment; preferred no active treatment if cancer was found; and preferred not to be screened (all significant at P ≤ 0.002).

Antenatal screening

One RCT evaluated interventions to increase both uptake and acceptability of antenatal HIV testing in pregnant women, a relatively new screening test with low uptake (prior to the study, uptake was only 1%). 21 Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals for the four interventions compared with the control were as follows: 6.54 (95% CI: 4.93–8.67) for minimal discussion protocol plus ‘all blood tests’ leaflet; 6.69 (95% CI: 5.06–8.86) for comprehensive discussion protocol plus ‘all blood tests’ leaflet; 6.24 (95% CI: 4.70–8.29) for minimal discussion protocol with HIV‐specific leaflet; 5.71 (95% CI: 4.29–7.60) for comprehensive discussion protocol with HIV‐specific leaflet. Thus each of the methods of directly offering the test resulted in a higher uptake than in the control group (6% uptake). However, there was no significant difference between the four methods of directly offering the test (χ2=3.9, d.f.=3, P < 0.27).

General knowledge about HIV was good and did not differ significantly according to intervention. However, the intervention did have a significant effect on knowledge specifically related to HIV infection (knowledge about breast feeding when infected with HIV: χ2= 267.4, d.f.=4, P < 0.001; knowledge of the anti‐HIV drug zidovudine: χ2=277.8, d.f.=4, P < 0.001). Knowledge of the screening test was not assessed. The HIV test appeared to be acceptable to women as 87% of women in the trial were in favour of offering an HIV test to all pregnant women.

Another RCT compared non‐directive information about prenatal testing (either in a group or an individual session) with routine information. 20 Neither intervention increased uptake of Down’s syndrome screening compared with routine information, and both interventions were less effective than routine information in increasing uptake of cystic fibrosis testing (RR=0.79, 95% CI: 0.63–0.98 for group and RR=0.82, 95% CI: 0.67–1.00 for individuals). There was no statistically significant difference between the two interventions in terms of the uptake of tests. However, not all of those who were offered the intervention attended the educational sessions. Attendance at extra sessions was 52% overall and lower at classes than individual sessions (author’s adjusted OR=0.45; 95% CI: 0.35–0.58). Individual and group sessions for Down’s syndrome and cystic fibrosis testing also increased the amount of relevant information that women felt they had received (actual data not reported). Those offered individual information were significantly less anxious than those in the routine information group (P=0.02) at 30 weeks on two anxiety scales, but at 6 weeks after delivery the difference was only significant on the state‐trait anxiety inventory scale (P=0.018). Women were more satisfied with the information they had received, although this did not translate into feeling surer that they had made the right decision.

Two RCTs evaluated different ways of presenting information on the risks and benefits of antenatal screening. 16 , 18 One RCT evaluated four different methods of presenting information about screening for Down’s syndrome. There was no statistically significant difference in uptake rates between the four groups. Also, the addition of an expanded information leaflet with a decision tree or video did not confer any benefit in terms of knowledge, decision‐making or anxiety to women offered serum screening for Down’s syndrome. 18 Another RCT compared the effectiveness of a touch screen computer system plus a leaflet, with a leaflet alone. The only significant difference in uptake between the two groups was that more women in the intervention group underwent detailed anomaly scanning (94% v 87%, P=0.001; RR=1.08, 95% CI: 1.03–1.13). 16 Knowledge about the four different screening tests significantly increased in both groups compared with baseline, but there was no greater gain in either group. 16 The anxiety level in the intervention group decreased significantly especially among nulliparous women. Both groups reported a high level of satisfaction with the information leaflet (> 95%), and a similar percentage of women in the intervention group reported that they would recommend the touch screen to other women. 16 Neither study assessed whether knowledge, decision‐making and anxiety were different in participants who decided to undergo screening compared with those who did not.

Discussion

Six studies were found which met the inclusion criteria relating to informed uptake. Four were RCTs of antenatal testing undertaken in the UK and two were studies of prostate cancer screening undertaken in North America. Three of the studies had the specific objective of evaluating informed choice or informed decision‐making in screening. 16 , 17 , 18 The other three were primarily studies of interventions to increase uptake and/or assess acceptability of screening. 15 , 20 , 21 It is not clear from the included studies whether the provision of information about risks and benefits increased or decreased the uptake of screening. In the two RCTs of antenatal screening that included a control group that received no information about the risks and benefits, uptake in the intervention groups was significantly higher than control for HIV testing, the same for Down’s syndrome screening, and lower for cystic fibrosis screening. 20 , 21 The trial of HIV screening, which also included an intervention group who received minimal information and an offer of a test (not informed choice), found that uptake was not significantly different to those who received more detailed information about the risks and benefits. The two trials of prostate screening included a control group that received no information about uptake of PSA screening. 15 , 17 Uptake was higher than control in one study 17 but lower (not statistically significant) in the other. 15

Two studies gave information about both risks and benefits of screening to all randomized groups. 16 , 18 Neither found that interventions such as videos, information leaflets with decision trees and touch screen computers conveyed any additional benefits over well‐prepared leaflets in improving understanding, knowledge, satisfaction or decision‐making. There was some evidence, however, to suggest that a computer touch screen may reduce anxiety in women. 16 The other two trials also reported no difference in effectiveness between interventions that gave information on risks and benefits (individual vs. group sessions and minimal vs. comprehensive discussion). 20 Thus at the present time there is some evidence to suggest that changing the format whilst retaining the same content about risks and benefits, does not alter knowledge, satisfaction or decisions about screening. It is not clear, however, if knowledge, decision‐making and satisfaction differ between those who decide to undergo screening and those who do not.

In the study that compared informed choice interventions with routine information, women had greater knowledge and satisfaction and less anxiety in the intervention groups. 16 , 20 In the other RCT, knowledge specifically relating to HIV infection was increased in the intervention groups compared with a control that received no intervention.

Currently there is a lack of empirical evidence about the likely effects of providing information regarding the risks and benefits of participation in screening programmes. There are also a number of issues that need to be addressed, some of which are outlined in the following section.

Relevance of informed uptake

Screening can be carried out with the aim of primary prevention (e.g. screening for risk factors such as hypertension), secondary prevention (e.g. cancer screening) or tertiary prevention (e.g. screening for sensori‐neural deafness). It could be argued that informed choice is not appropriate for all these screening tests. For example, should phenyl ketonuria (PKU) screening for infants be open to parental refusal? Also, should the informed choice be waived for screening tests for infectious diseases such as tuberculosis where not only the health of the individual is at stake but also the health of society as a whole? Furthermore, screening for risk factors such as hypertension may not warrant the same amount of emphasis on informed choice as screening for genetic disorders. These are further questions that need to be raised to inform policy‐making and debate in the important area of extending informed choice from treatment to screening.

Information

A number of issues surround the provision of information in informed uptake, not least the question as to whether it is ethical to continue to screen individuals who may not be fully aware of the risks, benefits and possible consequences of the procedure. To use, as many current screening programmes do, interventions such as letters that do not contain an element of education or to use leaflets which present only information in favour of screening could be seen as unethical. Information is a key component in the provision of informed uptake, but is it simply enough to provide a leaflet outlining both the benefits and risks of screening? Individuals vary in their levels of understanding and also their preferences for the presentation of data, i.e. whether the data are presented in written form or verbally, and whether the risks and benefits are presented quantitatively or qualitatively. 22 The effective presentation of information therefore requires consideration.

Concerns have been raised about the quality of information currently available to help inform decisions to undergo screening. For example, a recent survey in Australia of available mammography information leaflets found that information about the accuracy of screening tests was provided only occasionally, sensitivity was given in 26% of leaflets and specificity was not considered in any of the leaflets. 23 Similarly, a need to improve the quality of the information that women receive about cervical screening has been identified. 24 There are a limited number of guidelines and checklists to appraise the quality of written consumer health information, but one has recently been developed called DISCERN. 25 A guide to producing health information for patients and members of the public has also been published. 26

Knowledge

Interventions providing educational materials in any form may fulfil the need to provide individuals with information but if this has no affect on knowledge or decision‐making then it can not be effective at achieving informed uptake. Recent surveys have shown that knowledge about screening is limited. For example, in the first 5 years of operation, women participating in the NHS cervical screening programme were reported to be less aware of the limitations of screening than of the benefits. 27 In addition an individual’s knowledge of testing often varies. 28 It is therefore important to assess the level of knowledge as well as the amount of information given.

Decision‐making

Decision aids have been developed to help people to make specific and deliberative choices among options. They can improve knowledge, reduce decisional conflict and stimulate people to be more active in decision‐making without increasing their anxiety. 29 In order for a decision to be truly informed it should not only be based on knowledge, but should be consistent with the individual’s beliefs. Often studies assess the knowledge of participants, but few include a measure of the decision‐making process. 6 This is reflected in the lack of measures to assess informed uptake that incorporate both knowledge and the individual’s beliefs. One measure for use in prenatal Down’s syndrome screening is currently being developed. 30

It is unlikely that decisions are based solely on the information given. Other factors including participants’ attitudes/beliefs and their cultural, social and religious backgrounds are likely to influence decision‐making. In prenatal screening the possibility of giving birth to an affected child or having a termination means that the consequences of the decision may have wider effects and other family members may be involved in the decision. Also, even with a full understanding of screening, it is unlikely that all will become fully autonomous decision‐makers. In some cases individuals may not wish to make such decisions about their health‐care and to force these individuals to make decisions could also be considered unethical. In this situation shared decision‐making may be a compromise, with both the health‐care provider and the individual working through the process together and coming to a mutually agreed decision. In screening, however, this is likely to be a difficult and time‐consuming process compared with traditional methods that do not seek informed consent. Furthermore, some screening programmes, such as those for cervical and breast cancer, are population based and shared decision‐making is therefore inappropriate.

Tension between informed uptake and actual uptake

Up until recently the main focus of attention has been solely to increase the uptake of screening. However, in many countries such as the UK the issue of informed consent and informed uptake has arisen through the recognition that screening may also have associated harms as well as benefits for participants. Tensions can arise between the need to inform each participant about the benefits/risks of screening and the need for policy makers to achieve significant levels of uptake in order to maintain the viability of screening programmes. It has been argued, for example, that if pre‐test counselling for neonatal screening was more complete and informed consent required, public acceptance and uptake might not be as great as figures from current programmes suggest. 31 There is also some evidence to suggest that informed consent decreases patient interest in PSA screening. 15 , 32 Therefore, care needs to be taken that any messages about the limits of screening do not reduce the uptake of effective screening tests among those most likely to benefit.

In contrast, it has been argued that, above all, patients’ autonomy should be respected, including their right to decide not to undergo screening, even when refusal may result in harm to themselves. 2 A distinction has to be made therefore between ways of increasing uptake at all costs (i.e. by emphasizing only the benefits of screening) vs. ways of minimizing barriers (i.e. access) to uptake among those who choose screening. The choice to undergo screening should be based on a full understanding of the likely benefits, limitations and harm.

Many policies encourage health professionals to increase uptake rather than informed uptake. Some medical practices foster the need for health‐care providers to persuade individuals to undergo screening. For example, such is the importance of high uptake that targets for breast cancer screening and cervical cancer screening are now one of the performance indicators for general practitioners (GPs) and health authorities in the UK. 33 The recently published UK ‘NHS Plan’ also aims to extend the number and range of screening tests performed. 34 In the case of Pap smear screening in the UK, GPs are paid an incentive by health authorities for achieving high coverage rates. 35 It has been argued that target payments work against the spirit of enabling individuals to make an informed choice about whether or not they want to be screened. 36 An alternative to offering incentives for the number of individuals screened has been suggested. Any individual who had signed a form to indicate that they do not wish to participate in the screening programme would be included in target numbers. 37 It is unlikely that the introduction of such a policy would lead to large numbers of people opting out, but it would prevent those individuals who do not want to participate from coming under undue pressure. 37 Non‐uptake can also be informed and a person’s decision not to participate should be respected. These are just a few of the issues that need to be considered when introducing the ideal of informed uptake.

Conclusions

There is currently limited evidence available about the most effective ways of presenting information about the risks and benefits of screening. Two trials found that different ways of presenting information had little effect over leaflets. There was some suggestion, however, that a touch screen may be of some use. It is also not known if and how giving information about risks and benefits will affect outcomes such as uptake, knowledge and decision‐making. Enabling informed choice in screening is a complex process that needs careful consideration.

Implications for further research

There is a need to develop valid measures of informed choice in screening that reflect components such as knowledge, values and decision‐making. Alongside the development of such measures there is also a need for more well‐designed RCTs to evaluate formats and presentation of information about the risks and benefits on screening. Informed choice should be the primary, not the secondary, outcome of any study and should include measurement of both informed uptake and non‐uptake.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lisa Mather for carrying out the literature search, Susan Michie and Wendy Graham for providing additional unpublished data, Hilary Bekker for helping to develop the inclusion criteria, Andy Clegg for developing the original HTA report protocol, and members of the expert panel (for commenting on the HTA report).

The original report was funded by the Health Technology Assessment Programme. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS Executive.

Appendix 1 Search strategy

Electronic databases searched were: MEDLINE (1966 to October 1998), BIDS Science Citation Index (1981 to October 1998), BIDS Social Science Index (1981 to October 1998), Econlit (1969 to October 1998), EMBASE (1985 to October 1998), Cancerlit (1985 to October 1998), DHSS data (1985 to October 1998), Dissertation Abstracts (1985 to October 1998), ERIC (1985 to October 1998), HealthStar (1985 to October 1998), ASSIA (1985–97), Pascal (1985 to October 1998), SIGLE (1980 to October 1998), CINAHL (1982 to October 1998), Sociofile (1974 to October 1998), PsycINFO(1985 to October 1998), SHARE (Kings Fund), Library of Congress database, NHS CRD DARE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, and the National Research Register. A further search was undertaken to identify any relevant trials published from 1998 to August 2000. MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, CINAHL and PsycLIT (November 1998–present), using the following search terms: mass‐screening or screening or (antenatal/prenatal screening or testing) combined with information or education or informed choice or informed uptake or informed decision* or shared decision* combined with randomized‐controlled‐trials or controlled‐clinical‐trials or rct* or randomized controlled trial* or randomized controlled trial* or controlled clinical trial* or evaluation study or evaluation studies.

The Journal of Medical Screening was hand‐searched for all relevant reports, from Issue 1 (1994) to December 1999.

References

- 1. Department of Health . First Report of the National Screening Committee London: Department of Health, 1998.

- 2. Austoker J. Gaining informed consent for screening is difficult‐but many misconceptions need to be undone. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319: 722–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bekker H, Modell M, Denniss G et al Uptake of cystic fibrosis testing in primary care: supply push or demand pull? British Medical Journal, 1993; 306: 1584–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raffle AE. Informed participation in screening is essential. British Medical Journal, 1997; 314 (7096): 1762–1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thornton H. Screening for breast cancer: recommendations are costly and short sighted. British Medical Journal, 1995; 310: 1002–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bekker H, Thornton JG, Airey CM, Connelly JB. Informed decision‐making: an annotated bibliography and systematic review. Health Technology Assessment, 1999; 3: 1–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCormick J. Medical hubris and the public health: the ethical dimension. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 1996; 49: 619–621.DOI: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00039-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. General Medical Council . Seeking Patients’ Consent: the Ethical Considerations London: General Medical Council, 1999.

- 9. Faden R, Chwalow J, Holtzman N, Horn S. A survey to evaluate parental consent as public policy for neonatal screening. American Journal of Public Health, 1982; 72: 1347–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jepson R, Clegg A, Forbes C, Lewis R, Sowden A, Kleijnen J. The determinants of screening uptake and interventions for increasing uptake: a systematic review. Health Technology Assessment, 2000; 4: 1–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . Undertaking Systematic Review of Research on Effectiveness. CRD Guidelines for Those Carrying out or Commissioning Reviews York: University of York, 1996.

- 12. Sinclair J & Bracken M. Clinically useful measures of effect in binary analyses of randomized trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 1994; 47: 881–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oakley Davies H, Kinloch Crombie I, Tavakoli M. When can odds ratios mislead? British Medical Journal, 1998; 316: 989–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. RevMan 4.0. Oxford: Update Software, 1999.

- 15. Flood A, Wennberg J, Nease RJ, Fowler F, Ding J, Hynes L. The importance of patient preference in the decision to screen for prostate cancer. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1996; 11: 2342–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Graham W, Smith P, Kamal A, Fitzmaurice A, Smith N, Hamilton N. Randomised controlled trial comparing effectiveness of touch screen system with leaflet for providing women with information on prenatal tests. British Medical Journal, 2000; 320: 155–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davison B, Kirk P, Degner L, Hassard T. Information and patient participation in screening for prostate cancer. Patient Education Counselling, 1999; 37: 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Michie S, Smith D, McClennan A, Marteau T. Patient decision‐making: an evaluation of two different methods of presenting information about a screening test. British Journal of Health Psychology, 1997; 2: 317–326. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simpson WM, Johnstone FD, Boyd FM, Goldberg DJ, Hart GJ, Prescott RJ. Uptake and acceptability of antenatal HIV testing: randomised controlled trial of different methods of offering the test. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316: 262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thornton JG, Hewison J, Lilford RJ, Vail A. A randomised trial of three methods of giving information about prenatal testing. British Medical Journal, 1995; 311: 1127–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Simpson WM, Johnstone FD, Boyd FM et al A randomised controlled trial of different approaches to universal antenatal HIV testing: uptake and acceptability. Annex: antenatal HIV testing – assessment of a routine voluntary approach. Health Technology Assessment, 1999; 3: 1–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mazur D & Merz J. Patients’ interpretations of verbal expressions of probability – implications for securing informed consent to medical interventions. Behavioral Sciences and Law, 1994; 12: 417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Slater EW, JE. How risks of breast cancer and benefits of screening are communicated to women: analysis of 58 pamphlets. British Medical Journal, 1998; 317: 263–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Davey C, Austoker J, Jansen C. Improving written information for women about cervical screening: evidence‐based criteria for the content of letters and leaflets. Health Education Journal, 1998; 57: 263–281. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann B. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 1999; 53: 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Entwistle V & O'Donnell M. A Guide to Producing Health Information Aberdeen: Health Services Research Unit, 2000.

- 27. National Co‐ordinating Network . Report of the First Five Years of the NHS Cervical Screening Programme Oxford: National Co‐ordinating Network, 1994.

- 28. Marteau T. Towards informed decisions about prenatal testing: a review. Prenatal Diagnosis, 1995; 15: 1215–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O'Connor A, Rostom A, Fiset V et al Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic review. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319: 731–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marteau T, Dormandy E, Michies S. A Measure of Informed Choice. Health Expectations, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31. Edwards A. Pretest counselling and informed consent should be prerequisites. British Medical Journal, 1996; 312: 182–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wolf AM, Philbrick JT, Schorling JB. Predictors of interest in prostate‐specific antigen screening and the impact of informed consent: what should we tell our patients? American Journal of Medicine, 1997; 103: 308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Department of Health . The New NHS: Modern and Dependable. A National Framework for Assessing Performance Consultation Document London: Department of Health, 1998.

- 34. Department of Health . The NHS Plan. A Plan for Investment. A Plan for Reform London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 2000.

- 35. Department of Health . The Performance of the NHS Cervical Screening Programme in England. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General London: The Stationary Office, 1998.

- 36. Anderson C & Nottingham J. Bridging the knowledge gap and communicating uncertainties for informed consent in cervical cytology screening; we need unbiased information and a culture change. Cytopathology, 1999; 10: 221−218.DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.1999.00198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Foster P & Anderson C. Reaching targets in the national cervical screening programme: are current practices unethical? Journal of Medical Ethics, 1998; 24: 151–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]