Abstract

Objective To examine the effects of providing recordings or summaries of consultations to people with cancer and their families.

Design Systematic review.

Data sources MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cancerlit, EMBASE and other electronic bibliographic databases. Bibliographies of relevant papers.

Selection criteria Randomized and non‐randomized controlled trials of the provision of taped recordings or written summaries of consultations to people with cancer and/or their families.

Main results Eight randomized controlled trials were found, all involving adult participants. No non‐randomized controlled trials were found. The quality of the studies was generally poor. Between 83% and 96% of people who received recordings or summaries found them useful to remind them of what was said and/or to inform family members and friends about their illness and treatment. Of seven studies that assessed recall of information given during the consultation, four reported better recall among the groups that received recordings or summaries than among control groups. Receiving a recording or summary had no significant effect on anxiety or depression between the groups. None of the included studies assessed survival or health outcomes other than psychological outcomes.

Conclusions Wider use of consultation tapes and summary letters could benefit many adults with cancer, without causing additional anxiety or depression, but consideration should be given to individuals’ circumstances and preferences.

Keywords: communication, consultation, correspondence, medical oncology, review literature, tape recording

Introduction

Modern medical ethics promote patients’ rights to be informed about their medical conditions and to participate in decision‐making about tests, treatments or other procedures, including clinical trials. The provision of information and encouragement to participate in treatment decisions raise particular issues for people with cancer due to its chronic and life‐threatening nature, the fear that is widely associated with its diagnosis, the uncertainty of its prognosis and the severe side‐effects of many treatments. 1

Improving information for patients is a key component of United Kingdom (UK) health policy. 2 , 3 , 4 Many, but not all, people with cancer and their families want and need more information than they usually receive in the course of their care. 5 , 6 , 7 They need different types of information at different times and for different purposes, but often feel unable to access information at appropriate times. 8 Many patients expect to be involved in care management decisions. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Effective patient‐practitioner communication is central to patient participation in decision making.

However, people often find it difficult to understand and remember information that they are given during consultations, especially if they are distressed. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 They may be expected to understand a lot of complex information without any supporting frame of reference. 19 Other potential barriers to communication include limited access to cancer practitioners, poor communication skills, 20 poor health, lack of medical knowledge, lack of familiarity with terminology, brevity of the interview, learning difficulties, cultural or language differences, shock and anxiety, 21 denial, 22 , 23 and an absence of any record for the patient to review. 24

We report on a systematic review of studies that have evaluated the provision of recordings or summaries of consultations to people with cancer. An extended version of the review is available in the Cochrane Library. 25

Methods

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (1963–1998), Cochrane Library (1999), CINAHL (1982–98), PsycLIT (1967–98), Sociofile (1974–98), Cancerlit (1975–98), Dissertation Abstracts (1861–1998), EMBASE (1985–98), IAC Health and Wellness (1976–98), JICST (1985–98), Pascal (1973–98), ERIC (1966–98), Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts (1973–98), Mental Health Abstracts (1969–98), AMED (1985–98), CAB Health (1973–98), DH‐Data (1983–98), MANTIS (1987–98) and ASSIA (1987–98).

Search strategies were devised for each database. Bibliographies of identified studies were also checked. There were no language restrictions. The full search strategies are available from the first author.

Selection criteria

Randomized, or controlled trials of audiotapes, videotapes or written summaries of consultations provided to people with cancer and/or their families were eligible for inclusion. Two reviewers independently assessed the relevance of titles and abstracts retrieved from the searches and assessed the full reports of potentially relevant studies.

Quality assessment

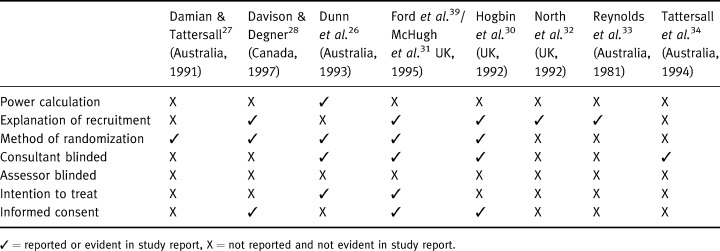

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed against six criteria associated with the power of the studies and the potential for bias to influence results. These included the following: statistical power calculation, explanation of method of recruitment, method of randomization, consultant blinding, assessor blinding, and intention to treat. One aspect of ethical quality, participants’ informed consent, was also assessed.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data relating to the interventions, participants, settings and study design were extracted onto a pro‐forma. Outcomes data were grouped broadly into three effect types: information recall or understanding; experience of health care (including participation in subsequent consultations, complaints, etc.); and health and well‐being. Data about participants’ uses and opinions of their recordings and summaries were also extracted. Data were extracted independently by one reviewer and checked by at least one other reviewer. We tried unsuccessfully to contact the author of one included study for clarification. 26

A qualitative synthesis of the study findings is presented, as studies were too heterogeneous to allow a statistical pooling.

Results

Approximately 3000 articles were identified and 18 were considered in detail. Eight randomized controlled trials reported in nine published papers 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 met the inclusion criteria for this review (agreement among reviewers on the inclusion of articles was 100%). No non‐randomised controlled trials were found. All included studies were single‐centre trials. The total number of participants per study ranged from 34 to 182.

Methodological quality

Table 1 summarizes the quality of reporting of study methods against seven criteria.

Table 1.

Summary of methodological quality of studies

Table S2 summarizes the participants, interventions and results of the eight trials included in the review. The studies varied considerably in terms of the interventions studied, participants and outcomes assessed. The interventions included: providing a blank audiotape to people before they went into their consultation and encouraging them to ask the consultant to record the consultation; 28 offering or giving people an audiotape recording at the end of the consultation; 26 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 and posting people a written summary of the key points discussed in their consultation. 27 , 34 The consultants in two studies used checklists to ensure that all standard information points were covered during the consultation. 27 , 34

Four studies involved only one consultant 26 , 27 , 30 , 34 and the same consultant was involved in three of these studies. Of the other studies, three involved two 28 , 32 , 33 and the other involved a team of five consultants. 29 , 31 Patients, as opposed to consultants, were the unit of randomization in all the studies.

The participants in all studies were adults. They varied, however, in terms of the type of cancer they had, the length of time since diagnoses and whether they received ‘good news’ or ‘bad news’ during their consultations.

Uses and opinions of the interventions

Table S3 summarizes participants’ uses and opinions of the interventions. It was consistently reported that most people who received recordings or summaries of their consultations valued them. Across the seven studies that provided data, between 83% and 96% of people receiving tapes or letters said they had found them useful. Usefulness was defined in terms of providing a reminder of what was said in the consultation and/or to inform family members and friends about their cancer and its treatment. One study found that people who received bad news found a summary letter significantly more useful than people who received good news. 27 Another study reported that the more anxious the patient and the worse they considered the news, the less they liked receiving a reminder of the consultation. 34

Information recall and understanding

Of seven studies that assessed recall of information given during the consultation, four reported better recall among the groups that received personalized recordings or summaries than among comparison groups. 26 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 32 Two studies found no significant differences between the groups. 30 , 34

One study found that participants in the control group recalled a greater percentage of presented facts than did those in the intervention groups. 33 However, the same study found that people in the control group were presented with fewer facts of interest.

Experience of health care

Of four studies that assessed participants’ satisfaction, two found that those who received a recording or summary were more satisfied with the amount of information they were given than were those in the control group. 26 , 27 Participants in the study that compared a tape with a letter were more satisfied with the tape than with the letter for reminding them of what the doctor had said. 34 One study found no differences in satisfaction between the tape and control groups. 33

Two studies assessed the effect of the intervention on levels of patient participation in a subsequent consultation. One study found that a significantly higher proportion of participants in the intervention group assumed a more active role in treatment decision‐making than did participants in the control group. 28 Owing to the complex intervention, however, it is not possible to attribute this behaviour to the audiotape alone. In the other study, more participants in the intervention group asked for clarification of specific details during their second consultation than did participants in the control group. 29 , 31 Also, more participants in the control group requested information already supplied to them in their first consultation than did participants in the intervention group.

None of the studies reported any complaints or litigation relating to either the intervention(s) or the health professional’s behaviour during the consultation.

Health and well‐being

Six studies assessed anxiety and/or depression. 26 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 34 None of them found any statistically significant differences between the groups that received and did not receive recordings or summaries of their consultations. One study, however, did find mixed results among participants in the intervention group, as psychiatric morbidity increased significantly at follow‐up in those with a poor prognosis compared with those with a better prognosis. 29 , 31

None of the included studies assessed survival or health outcomes other than psychological outcomes.

Discussion

Potential benefits of improved communication include increases in patient satisfaction, 35 psychological adjustment and coping, reduction in distress 36 and greater concordance in treatment decision‐making and improved response to treatment. 37 Various strategies/interventions to improve the extent to which patients’ information needs are met have been tested. These include telephone‐based information and advice lines, 38 , 39 , 40 and printed and audiovisual information materials. 41 , 42 The provision of audiotapes or written summaries of consultations has also been tested using different study designs and with varying results. A recent review concluded that the majority of participants benefited from receiving audiotapes, although the efficacy and utility of consultation audiotapes for cancer patients required further examination. 43 However, the review failed to identify a number of published studies, including two randomized controlled trials. In addition, it failed to assess the methodological quality of the reported studies.

Main results

The evidence from the studies included in this systematic review suggests that giving a tape or written summary of a consultation to people with cancer can significantly increase their information recall and understanding and their satisfaction with the information given. There is no clear evidence that these interventions affect psychological health. There is some evidence to suggest that the provision of consultation recordings or summaries might enhance patients’ participation in subsequent consultations and in decisions about their care.

The studies suggest that most cancer patients positively value a record of their consultation (Table S3).

Study validity

The included trials represent the best available evidence for evaluating the effectiveness of these interventions, although the overall quality was poor. The checklist of methodological quality (Table 1) shows that most studies were open to several common threats to validity (although it was sometimes hard to determine if poor research design or poor reporting was the problem). Only one study reported a power calculation to determine the sample required to detect an effect size at a given probability level. Explanation of recruitment and randomization are important to assess the threat of selection bias. Five studies explained either the method of recruitment or randomization, and three explained both, so there were potential problems with selection bias. Four studies blinded consultants to patients’ allocation (with some interventions this would not be possible) and none reported blinding outcome assessors. Two studies used an intention to treat approach to analysis to guard against type I error. Hence, most of the studies show serious potential threats to validity and their results should be viewed cautiously.

These information‐giving interventions are very context specific and arguably remain relevant for a relatively short period of time (at the next consultation, it is likely that different information will be provided and different issues discussed). Further research is needed to study the effects of recordings at different key phases of care, including diagnosis, treatment, cessation of treatment, relapse and advanced stages. Further research is also needed to study the effects of providing recordings or summaries of a series of consultations to assess cumulative effects on the consultation process and outcomes.

Applicability

Regarding the applicability of the studies, the effectiveness of recordings or summaries of consultations may depend in part on the content of the consultation and the way it was conducted. Most of the trials identified involved only one or two consultants who probably had a particular interest in communication issues. While it is quite appropriate to enlist a good communicator to test the basic efficacy of recordings and summaries of consultations, trials involving a wider range of consultants or different health professionals are needed to assess the effectiveness of these interventions in routine practice.

All the studies were done in Australia, North America and the UK, where disclosure of information appears to be generally favoured by health practitioners and consumers. It may not be appropriate to generalize their findings to other cultures with different values and attitudes regarding disclosure of a cancer diagnosis.

The consultation process and content may be affected by participants’ awareness that they are being recorded. This might lead consultants to adopt a more planned approach to exchanging information with patients, which could help to ensure that at least a minimum amount of information/discussion concerning their disease, prognosis, tests and treatment is offered. It could also help to ensure that adequate time is allowed for the consultation and that it is conducted in an appropriate environment.

The value of recordings is likely to be linked to the quality of consultation recorded, although this relationship remains to be explored. It is conceivable, for instance, that recordings of poorly conducted consultations may still be useful to recipients to help them to clarify causes of dissatisfaction or unmet needs.

Appropriateness of measured outcomes

As with many communication interventions, providing recordings or summaries of consultations to people with cancer might impact on a variety of processes and outcomes that can be measured and valued in different ways. 44 There have been no randomized clinical trials assessing the effects of these interventions on survival, physical health status or general quality of life of people with cancer. Most of the studies that have evaluated the provision of recordings or summaries of consultations have investigated the effects of the interventions on psychological outcomes. This may reflect the fact that health professionals traditionally assumed that information about health problems and treatments causes anxiety and that anxiety is a bad thing. 45 The studies reviewed here provide some evidence that recordings and summaries of consultations do not exacerbate anxiety except, perhaps, among people with poor prognoses.

Implications for research

More research is needed to assess the effectiveness of consultation recordings and summaries in a wider range of cancer treatment settings involving a range of health professionals. Further research is also needed to study the effects of recordings at different phases of care and the effects of providing recordings or summaries of a series of consultations.

More research is needed to determine which people are more or less likely to benefit from this type of intervention in order to maximize benefits and minimize harm. Further and more detailed research is needed to understand the benefits that participants might experience from listening to a consultation tape or reading a summary letter. Benefits, such as relief from the burden of explaining their illness to family, friends and others, could usefully be explored. Other important benefits, such as feelings of reassurance and support, could be examined. More research is also needed into the relationship between patients’ expectations and the value they place on information given. It is plausible that each person may have an individual ‘threshold’ beyond which further information would yield diminishing ‘added value’.

The costs of the interventions also need to be considered. None of the reviewed studies contained economic evaluations, although one study 32 reported that audiotaping consultations was cheap and easy.

None of the studies reported any problems with complaints or litigation arising from the use of the interventions, although most studies had only short follow‐up periods. Two surveys carried out in Australia have suggested that neither doctors nor their defence organisations were concerned about the legal consequences of giving people recordings or summaries of their consultations. 34 , 46 The possible legal consequences of using these interventions in other countries are not clear.

Conclusions

Although many doctors remain opposed to offering patients personalized information aids, practices and perspectives are changing. 47 On balance, the available research evidence suggests that the provision of recordings or summaries of key consultations would benefit most adults with cancer without causing any additional anxiety or depression. Although there is scope for further research to improve our understanding of the effects of giving people records of their consultations, health professionals might want to consider routinely offering people tape recordings or written summaries of their consultations. Decisions about who should be given the interventions should take into account people’s medical condition (especially their prognosis), the support they have available, and their expressed preferences for a record of what has been said. If ‘bad news’ has been delivered, other interventions such as follow‐up counselling may be more appropriate. As for any healthcare intervention, consent should be obtained before the recording or summary is provided. Recordings should be given in the context of an integrated patient information service that allows patients and family members to follow‐up any additional information needs arising from them.

Acknowledgements

We thank Julie Glanville for help with literature searching and the following individuals for helpful comments on the protocol and draft of this review: Hilda Bastian, Jaqueline Droogan, Tim Eden, Chris Eiser, Maggie Emslie, Lesley Fallowfield, Kate Flemming, Julie Glanville, Alan House, Martin Ledwick, Deborah Lister‐Sharp, Fiona McInnes, Becky Miles, Mary Miller, Carolyn Pitceathly, Amanda Ramirez, Patricia Sloper, Martin Tattersall, Hazel Thornton and Mari Lloyd‐Williams.

Funding: NHS National Cancer Research and Development Programme. Vikki Entwistle is partly funded by a Special Research Fellowship from the Leverhulme Trust. The Health Services Research Unit receives core funding from the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Executive Health Department. NHS CRD receives core funding from the Research and Development Directorate of the NHS.

Supplementary material

The following material is available from http://www.blackwell‐science.com/products/journals/suppmat/HEX/HEX127/HEX127sm.htm

Table S2 Summary of participants, interventions and results

Table S3 Summary of use and opinions.

Supporting information

Table S2 Summary of participants, interventions and results Table S3 Summary of use and opinions

Supporting info item

References

- 1. Leydon GM, Boulton M, Moynihan C et al Cancer patients’ information needs and information seeking behaviour: in depth interview study. British Medical Journal, 2000; 320 : 909–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health . Patient Partnership: Building a Collaborative Strategy. Leeds: Department of Health, NHS Executive, 1996.

- 3. Department of Health . Information for Health: an Information Strategy for the Modern NHS 1998–2005. Leeds: Department of Health, NHS Executive, 1998.

- 4. The Scottish Office . Designed to Care: Renewing the National Health Service in Scotland. Edinburgh: The Scottish Office, 1997.

- 5. Beaver K, Bogg J, Luker KA. Decision making role preferences and information needs: a comparison of colorectal and breast cancer. Health Expectations, 1999; 2 : 266–276.DOI: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.1999.00066.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones R, Pearson J, McGregor S et al Cross sectional survey of patients’ satisfaction with information about cancer. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319 : 1247–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meredith C, Symonds P, Webster L et al Information needs of cancer patients in west Scotland: cross sectional survey of patients’ views. British Medical Journal, 1996; 313 : 724–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Edwards D. Face to Face. Patient, Family and Professional Perspectives of Head and Neck Cancer Care. London: King’s Fund, 1997.

- 9. Butow P, Dunn S, Tattersall M, Jones Q. Patient participation in the cancer consultation: evaluation of a question prompt sheet. Annals of Oncology, 1994; 5 : 199–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cassileth BR, Zupkis RV, Sutton‐Smith K et al Information and participation preferences among cancer patients. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1980; 92 : 832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fallowfield L. Giving sad and bad news. Lancet, 1993; 341 : 476–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sutherland HJ, Llewellyn‐Thomas HA, Lockwood GA, Tritchler DL, Till JE. Cancer patients: their desire for information and participation in treatment decisions. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 1989; 82 : 260–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thomasma D. Beyond medical paternalism and patient autonomy: a model of physician conscience for the physician‐patient relationship. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1983; 98 : 243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eden OB, Black I, MacKinlay GA, Emery AE. Communication with parents of children with cancer. Palliative Medicine, 1994; 8 : 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fallowfield L, Ford S, Lewis S. No news is not good news: information preferences of patients with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 1995; 4 : 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hogbin B & Fallowfield L. Getting it taped: the ‘bad news’ consultation with cancer patients. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 1989; 41 (4): 330–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Northhouse P & Northhouse L. Communication and cancer: Issues confronting patients, health professionals, and family members. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 1987; 5 : 17–46. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosenbaum E & Rosenbaum I. Achieving open communication with cancer patients through audio and videotapes. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 1986; 4 : 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rylance G. Should audio recordings of outpatient consultations be presented to patients? Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1991; 67 : 622–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ley P. Communicating with Patients: Improving Communication. Satisfaction and Compliance. New York: Croom‐Helm, 1988.

- 21. Ley P & Spelman MS. Communications in an out‐patient setting. British Journal of Social Clinical Psychology, 1965; 4 : 114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goss ME & Lebovitz BA. Coping under extreme stress: observations of patients with severe poliomyelitus. Archives of General Psychiatry, 1977; 6 : 423–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greer S. The management of denial in cancer patients. Oncology, 1992; 6 : 33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Butt H. A method for better physician‐patient communication. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1977; 86 : 478–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scott JT, Entwistle VE, Sowden AJ, Watt I. Recordings or summaries of consultations for people with cancer (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2001. Oxford: Update Software. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. Dunn SM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH et al General information tapes inhibit recall of the cancer consultation. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 1993; 11 : 2279–2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Damian D & Tattersall MH. Letters to patients: improving communication in cancer care. Lancet, 1991; 338 : 923–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davison BJ & Degner LF. Empowerment of men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. Cancer Nursing, 1997; 20 : 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ford S, Fallowfield L, Hall A, Lewis S. The influence of audiotapes on patient participation in the cancer consultation. European Journal of Cancer, 1995; 31a : 2264–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hogbin B, Jenkins V, Parkin A. Remembering ‘bad news’ consultations: an evaluation of tape‐recorded consultations. Psychooncology, 1992; 1 : 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- 31. McHugh P, Lewis S, Ford S et al The efficacy of audiotapes in promoting psychological well‐being in cancer patients: a randomised, controlled trial. British Journal of Cancer, 1995; 71 : 388–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. North N, Cornbleet MA, Knowles G, Leonard RC. Information giving in oncology: a preliminary study of tape‐recorder use. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1992; 31 : 357–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reynolds PM, Sanson‐Fisher RW, Poole AD, Harker J, Byrne MJ. Cancer and communication: information‐giving in an oncology clinic. British Medical Journal of Clinical Research Edition, 1981; 282 : 1449–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tattersall MH, Butow PN, Griffin AM, Dunn SM. The take‐home message: patients prefer consultation audiotapes to summary letters. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 1994; 12 : 1305–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cohen F & Lazarus RS. Coping with the stresses of illness. In: Stone GC, Cohen F, Adler NE (eds) Health Psychology. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass, 1979: 217–254.

- 36. Audit Commission . What Seems to Be the Matter: Communication Between Hospitals and Patients. London: HMSO, 1993.

- 37. Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain . From Compliance to Concordance. Achieving Shared Goals in Medicine Taking. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 1997.

- 38. Aaronson N, Visser Pol E, Leenhouts G et al Telephone‐based nursing intervention improves the effectiveness of the informed consent process in cancer clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 1996; 14 : 984–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Balas EA, Jaffrey F, Kuperman GJ et al Electronic communication with patients: evaluation of distance medicine technology. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1997; 278 : 152–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marcus A, Garrett K, Cella D et al Telephone counselling of breast cancer patients after treatment: a description of a randomized clinical trial. Psychooncology, 1998; 7 : 470–482.DOI: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199811/12)7:6<470::aid-pon325>3.0.co;2-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Horan PP, Yarborough MC, Besigel G, Carlson DR. Computer‐assisted self‐control of diabetes by adolescents. Diabetes Education, 1990; 16 : 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Meade CD. Producing videotapes for cancer education: methods and examples. Oncology Nursing Forum, 1996; 23 : 837–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McClement SE & Hack TF. Audio‐taping the oncology treatment consultation: a literature review. Patient Education and Counselling, 1999; 36 : 229–238.DOI: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00095-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Entwistle VA, Sowden AJ, Watt I. Evaluating interventions to promote patient involvement in decision‐making: by what criteria should effectiveness be judged? Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 1998; 3 : 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reiser S. Words as scalpels: transmitting evidence in the clinical dialogue. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1980; 92 : 837–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stockler M, Butow P, Tattersall M. The take‐home message: doctors’ views on letters and tapes after a cancer consultation. Annals of Oncolology, 1993; 4 : 549–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McDonnell D, Butow P, Tattersall M. Audiotapes and letters to patients: the practice and views of oncologists, surgeons and general practitioners. British Journal of Cancer, 1999; 79 : 1782–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S2 Summary of participants, interventions and results Table S3 Summary of use and opinions

Supporting info item