Abstract

Objective To explore the patient’s experience of venous ulceration and how it is shaped within primary care.

Design Qualitative grounded theory study.

Participants and setting Thirty‐nine patients, 33 nurses and 14 general practitioners in a major health district in England.

Results The findings indicate that patients with the chronic condition of venous hypertension are handled in an anomalous way within primary care when they present with ulcers on their lower limbs. The trajectory projections for the patients are not developed from the usual basis of a medically defined condition‐specific diagnosis but from a symptom‐specific diagnosis. This leads to an unusual context of care where there is a serious but unrecognized conflict of focus between the nurses and their patients. The nurses in this study tended to set priorities related to the ulcer and to the underlying pathology, whereas the patients wanted help in pain management and in normalizing their lives. The patients eventually came to a position of ‘guarded alliance’ 2 that in this study took one of three forms: adapting and enduring, emphasizing the positive, or negotiating for comfort.

Conclusion The acute care approach applied to patients with this chronic condition led to a situation where the professionals usurped the self‐care potential of the patients and navigated rather than piloted them through an acute phase of an underlying chronic illness. This in turn, led to poor quality of life for many of the patients and to frustration for the nurses who were failing to achieve the outcomes they desired. Both perspectives need to be encapsulated into the treatment approach for patients with this condition: healing the ulcer and normalizing the patients’ lives can and should form the basis of care.

Keywords: chronic illness, grounded theory, guarded alliance, shaping, trajectory, venous ulcers

Introduction and background to the study

The experience of venous ulceration is a common one, with approximately 1% of the population suffering from this most obvious sign of venous hypertension at some period in life. The underlying pathology is usually that of a chronic condition and at present no cures are routinely available: it might be possible to achieve healing of the ulcer but the underlying condition usually remains. In situations such as these where cure is not possible, efforts need to be directed towards palliation and normalization. However, one of the greatest barriers to the effective management of chronic illnesses and to the improvement of care for the individuals who live with them is the fact that the interventions and therapies applied to them were designed to treat acute rather than chronic illnesses:

‘This means, on the one hand, that the symptoms of the illness are treated instead of the person, and on the other, that the treatment aims only at curing instead of focusing on how to help the patient live with a long lasting illness.’ 3

This approach presents considerable problems for the individual sufferer because it means that his/her ulcer and its healing become the sole focus of professional interventions. In the process it becomes all too easy to lose sight of the person and his/her experience, that is, for the nursing perspective, to be lost.

It is perhaps unique to the management of this group of patients that the role of the nurse becomes one of ‘recasting the illness in terms of theories of disorder’ and in reconfiguring illness problems ‘as narrow technical issues’. 4 In other referral situations the doctor routinely gives at least a tentative medical diagnosis that the nurse can use as part of an holistic assessment to guide her practice. However, in the case of the patient with a leg ulcer, no such definition is made and the nurse must focus on the ulcer to find the clinical information denied her in the referral: the patients’ safety demands it and the effective management of the wound requires it. 5 She leaves the traditional nursing domain to provide a service to these patients: it is obvious to her that if the doctor had the requisite knowledge of leg ulceration he/she would have provided the diagnosis. It is equally clear that if she does not assume this part of a medical role, then the patient’s safety is jeopardized and she, in turn, has an uncertain base on which to make her decisions regarding treatment. As reasonable as all this may appear and as common as it is, it should not be forgotten that in these circumstances something crucial may be lost: the nurse–patient relationship may founder in the diagnostic quest.

It matters greatly to the patients that their experiences are translated into scientific accounts and measurements of disease. The failure on the part of the nurse to appreciate the differences between the disease and the illness as experienced affects the patients at every level. From the onset of symptoms the patient seeks meaning. To the individual his/her symptoms are the ‘mind’s subjective interpretation of the body’s real disease experience’ 6 but to the professional they may be merely indicators of pathology. The weight placed upon the objectively discernible signs indicates to the patient that his/her experience is assessed against an external standard and that when a discrepancy occurs, the objective will be held to be true. Bury 7 has coined the term ‘meanings at risk’ to describe the situations of potential conflict between the individual and others when the personal significance and definition of symptoms may be disputed.

The study

This paper deals with the experiences of 39 patients who had venous ulcers and who were cared for in primary care settings. The findings come from a larger study that explored both the personal experiences of patients and the professional management of venous ulceration. Ethics approval was obtained from the local medical ethics committee and access to individual patients and to the health professionals was achieved through attending professional meetings, explaining the purpose of the study and asking for the opportunity to conduct interviews with them and with their patients. A self‐ selecting sample of 14 doctors and 33 nurses asked the appropriate patients in their caseloads if they would be willing to participate. The 39 patients who agreed met with the researcher who explained the study, answered any questions and obtained formal consent. To be included in the study the patients had to be English speaking, willing and able to participate in an in‐depth interview, and have a working diagnosis of ‘venous ulcer’.

Using grounded theory, the initial sample was selected, not to be representative of certain demographic variables, but because it was where the phenomenon of interest to the researcher existed. 8 The research began with an interest in the substantive area of venous ulceration rather than with a research problem as such. The essential focus of the researcher was to discover the core concerns of the people who had venous ulcers and to allow those and the processes that resolved them to emerge unforced from the data. 9

The sample, then, did not set out to be representative in terms of demographic variables but in terms of the categories. Nevertheless, a summary of some of the characteristics may be of interest to some readers. Of the 20 district nurses, 18 trained after the new syllabus was introduced. Of the practice nurses, five of the 13 had at the time of interview completed the formal training for their role.

Of the patients four were male, 35 female. Only two of the men and one woman were under 65 years of age. The average age of the retired men was 67, and of the retired women 74. The length of time that the patients experienced active ulceration ranged from 5 months to 28 years, the average being 13 months. Most had experienced at least two episodes of ulceration.

Grounded theory uses both inductive and deductive approaches to theory construction and through constant comparison allows hypotheses to be generated and tested or ‘grounded’ in subsequent data. Ensuing sampling was done to increase the representativenesss of the categories generated. So, for example, when comments were made by patients being cared for by district nurses that their descriptions of pain were not being heard, the category of ‘professional deafness’ emerged. It was then important to determine if this category emerged in a group cared for by practice nurses.

The data from the patients were gathered during a single 45‐minute taped interview conducted either in the home of the patient or in the general practitioners’ surgeries. After a brief period of introduction each person was asked to describe how the ulcer began and what it had been like having this type of wound. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and the data analysis handled manually. Field notes and memos supplemented and expanded on the data. It was the ongoing and simultaneous collection and analysis of the data that led to the formulation of hypotheses and guided further data collection aimed at testing them. The constant comparative process of data analysis allowed the substantive theory to be developed, tested, revised and clarified over a period of 2 years. Data collection continued until saturation was achieved, that is until accounts became repetitive for information and yielded no new data.

The findings

The findings of this part of the study will be presented as they evolved in temporal order from the decision to consult followed by the nature of the medical encounter. The resulting referral for nursing management and the ensuing conflict of focus will then be explored by a discussion of the reciprocal impact. Finally, the strategies employed by the patients in coping with their situation will be presented and discussed.

The decision to consult: ‘I went because my legs hurt’

When the patients were individually interviewed and asked to describe how their ulcers had come about and how they had managed them, it became apparent that each of them had undertaken self‐care for periods of time ranging from 4 to 18 months. This approach was a logical one because their personal experience of wounds in the past had led them to believe that, given time, their wounds would heal. Self‐care ‘in its various forms, preventive, curative and rehabilitative… is the basic health behaviour in all societies past and present’. 10 Although professionals tend to view self‐care and care provided by others as inferior to their own, it is in fact professional care that is the supplemental form. 11

It is actually quite problematic for most people to know when they should consult a health care professional and the individuals with wounds on their lower legs who were interviewed for this study were no exception. The physiological changes that might eventually be seen to be part of the trajectory of venous hypertension often occurred very slowly over time and were incorporated into the ‘boundaries of normality’. 12 If the typical precursors of skin changes, pigmentation, varicosities and aching legs were not cause for consultation then, the presence of a wound would not cause them to seek professional help. However, in the end each made the decision to see the general practitioner (GP). The decision to do so was not made lightly. The main factor that led them to the doctor was the pain. The following two quotes were typical:

‘I just wanted summat for the pain, really, that were all.’

‘It was the pain made me go. In fact it made the ankle bone swell a bit… I had to have something to ease the pain.’

A secondary but important additional factor moving them towards the decision to consult was wound deterioration. In most cases the time since the wound appeared and the deterioration in appearance were used as reasons to explain why they decided to go to the doctor; there was overall difficulty in deciding to go to the doctor with ‘just a wound’. Comments were made such as:

‘You think its nothing – just a wound – and you leave it and of course, it didn’t get better, it got worse.’

‘It just went on and on and on and I thought I had better go to the doctor with it.’

Not one of the patients interviewed anticipated losing control of their care: each expected the health professionals to pilot them through the acute symptom phase while they themselves maintained control of the overall navigation of the illness trajectory.

‘I went to the doctor to see what they could supply me with’ said an older gentleman who had been self‐caring for his wound for over a year. He fully expected to carry on his own care following the consultation.

Another said: ‘Well I thought they might have some more modern treatment for it. I’m a nurse myself so I could dress it myself, I thought’.

They sought medical help because of their pain and the fact that their wounds were either failing to heal or deteriorating. Each had been self‐caring for a varying length of time. All expected to be given something to relieve the pain and advice or a prescription for something that would help them to manage their wounds more effectively and move them towards healing. None expected to become patients for longer than the appointment time.

The general practitioners

‘The nurse knows about wounds so I just refer them through to her.’

Fourteen general practitioners were interviewed in order to determine their approaches to the management of patients with leg ulcers. Everyone admitted readily that he or she didn’t know how to deal with these patients and therefore each was quite pleased to be able to refer them on to their nursing colleagues after writing prescriptions to deal with pain or infections. None was able to undertake even the most basic of Doppler assessments and none mentioned undertaking a complete medical examination as part of their initial consultation. Subsequent questioning of the nurses and patients indicated that a full medical work‐up was never in fact done: the examination was limited to the ulcer.

The importance of medical diagnosis has been described by Strauss et al. 13 in this manner:

‘Diagnosis is the health professional’s term for the beginnings of trajectory work. To do anything effective, other than just treat symptoms, the illness has to be identified. Once this is accomplished, the physician has the imagery of the potential course of the illness without medical intervention. The physician has the mapping of what the interventions might be, what might happen if they are effective and what resources are required to make them happen.’

Without such identification and mapping, all that does happen is sign‐ and symptom‐specific management. In this study it was common to find that the patients mentioned that the pain from their wounds was disrupting their lives and the doctors accordingly gave prescriptions for mild analgesics and sometimes antibiotics. The symptom‐specific diagnosis of ‘leg ulcer’ was made in each case and no further definition was seen as crucial for the ongoing management of the patients. This initial interview was often the last time the patients saw the doctor about their condition: all further management was handed over to the nursing staff.

How far this is from acceptable medical practice can be seen in the key literature. Browse, Burnand and Thomas 14 noted that ‘leg ulcers are so often a manifestation of distant disease that… a complete medical examination is essential in all patients’. Schofield and Hunter 15 list the numerous diseases that may be associated with a leg ulcer and it is apparent that diagnosis is not easy or simple when one considers the literature dealing with misdiagnosis. 16 , 17 The importance of full examination is further seen from the results of the studies carried out by Negus and Friedgood, 18 Sethia and Darke 19 and Negus: 20 accurate diagnosis can identify those patients in whom surgical interventions might eliminate the underlying cause of their ulceration.

Nursing management and reciprocal impact

‘I think leg ulcers are a traditional nurses job.’

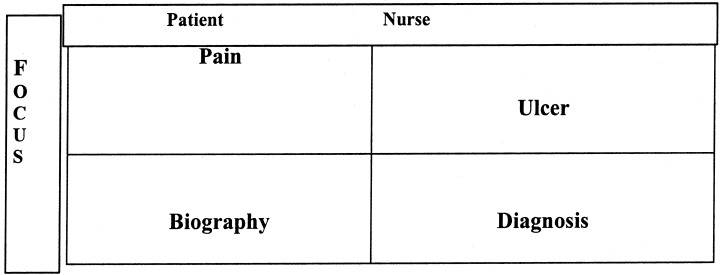

Perhaps this quotation from one of the nurses indicates the nursing approach best: it is ‘leg ulcers’ and not the person who is referred to. Holistic nursing care is often not achieved because the focus of the nurses’ attention is routinely centred on the wound and the meaning of the pain and other wound‐related factors in pathophysiological terms. The conflict in focus is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The conflict of focus.

The reciprocal impact is the way in which the management of care, with all its inherent dangers of compounding problems for the patient, interacts with the patient’s experience of illness, ability to carry out a chosen biographical trajectory and to simply live life as he/she chooses on a day‐to‐day basis. 21 The effect on the patient is marked and creates highly problematic symptoms and social problems. However, the effects are neither predicted nor expected by either nurses or patients.

Certain assumptions are made at the point of referral by both the patients and the nurses that eventually cause feelings of dissatisfaction in the nurses, but worse, provide the conditions for ongoing poor quality of life for the patients. The patients expect that the nurses will share their set of priorities automatically but this is not the case, particularly in the early months of treatment. This leads to ‘guarded alliance’ as has been described by Thorne and Robinson.22 Their qualitative study of health care relationships in a number of chronic illness contexts showed three evolving phases in the relationship of patients and their nurses: naïve trusting, disenchantment and finally guarded alliance. The same phases were found in this study of patients with leg ulceration. After the initial period of naïve trust when they relinquished care to the nurse because of the complexity of treatment with a multilayer bandage, they found that their wounds were not healing as quickly as they had hoped. The disruption of life caused by the nursing management of their slow‐to‐heal wounds and the accompanying pain was now added to by bandaging that prevented self‐care and precluded normal presentation of self in everyday life until healing had been realized.

Once a patient is on the treatment list of the practice or district nurse, it is very difficult for him or her to decline care. In fact, there was a feeling among many patients that even if the chosen approach was not working, it was best not to point this out to a doctor for fear of causing further disruption to often difficult interpersonal relationships with the nurses. The patients needed to find a way to get along with them to minimize their problems and attempt to maximize their control of their lives: they eventually entered a stage of guarded alliance. Their guarded alliance took one of three forms: adapting and enduring, emphasizing the positive, or negotiating for comfort.

Adapting and enduring

Adapting and enduring is a strategy that involved rearranging one’s life to meet the demands of the disease and its treatment. Unfortunately one of the things the patients had to adapt to and endure was their pain: the prime reason they had consulted the doctor in the first instance was never dealt with adequately.

The nurses did not expect their patients to have significant pain with their ulcers unless they were arterial in nature or infected. In the case of the former they assumed that there was nothing short of surgery that could be done for pain and in the latter they assumed that a swab and appropriate antibiotics would ameliorate the problem: their approach was congruent with the vast majority of the literature available until fairly recently. It is typical, for example, to find that pain is given as a feature of arterial but not of venous ulcers in the medical texts and to have that factor used in the diagnosis of ulcer type. Browse, Burnand and Thomas23 noted in their textbook of venous disorders that pain is a feature of ischaemic ulcers but that ‘discomfort’ is a feature of venous ulcers. They suggested, moreover, that it is ‘almost always relieved by elevation’. Only in the last few years has pain been recognized as a feature of venous ulceration. Attention was first drawn to this problem in the medical literature: Gross and his colleagues 24 referred to the fact that pain was a problem in 88% of their patients and Burton 25 was the first author to indicate that pain might not have diagnostic value because venous and arterial ulcers might produce equal degrees of pain. However, pain as a major quality of life issue has only begun to appear in the nursing literature within the last 5 years and so far has received very limited attention. 26 , 27 , 28

A typical quote from a district or practice nurse still reflected the patient experience dictated by the medical literature of the earlier period.

‘Oh, venous ulcers aren’t much of a problem. They get a tingling in the ulcer bed itself but once they are dressed and settled, they are usually okay. Give or take the odd paracetamol they haven’t needed a lot of analgesia for pain relief. It seems that the arterial ones are the little beggars… I’ve known people crying with arterial ulcers.’

In this study it was of interest to find that the drugs most commonly prescribed for these patients were paracetamol (Acetaminophen, 500 mg) or Co‐codamol (paracetamol, 500 mg and codeine 8 mg). The patients routinely found these insufficient but because there was no ongoing assessment of their pain by the nurses and because they rarely saw the doctors after the initial consultation, their quality of life was seriously compromized without a health care professional being aware of what was happening. Roe and her colleagues 29 found a similar pattern of care: of 146 community nurses caring for patients with chronic leg ulcers, 55% did not assess their patients’ pain. The patients simply tried to adapt to their situation and where relief from pain and disruption was not possible, they mostly just endured the situation.

‘Did you mention your pain to the nurse or the doctor?’

‘I did — to the nurse and she said “Well you could get some pain killers you know” but I didn’t bother because I think you’re better without drugs if you can manage it at all. Plus, the doctors are always busy; you don’t like taking their time up do you? I tend to think they’ll think you’re wasting their time.’

‘Dr X said she would give me something for pain… when they got so bad where I couldn’t really stand it, I would take paracetamols.’

‘Were they adequate for you?’

‘No, not really. I don’t know if you have spoken to anyone else with ulcers but anyone would tell you that is a horrible pain — it gnaws at you all the time. It eases from time to time but it always comes back…’

The patients in these situations sometimes placed themselves at serious risk because of their lack of knowledge of side‐effects or of drug interactions. Some patients admitted using additional drugs such as Co‐Proxamol (dextropropoxyphene hydrochloride and paracetamol) that had been prescribed at another time for other conditions. One man added:

‘I’ve gone out to the pub with it aching like anything. But after three or four pints of beer — it’s like a drug, isn’t it? — It takes the pain away. I also take the tablets though.’

The ability of these patients to lead normal lives, particularly in the early months, was found to be severely limited. Their response of adapting and enduring increased their difficulties/distress. Many reported to the researcher that they had difficulties in sleeping and in eating because of their pain; some expressed a reluctance to be around children in the family for fear of unintentional injury or indicated that they were now unable to socialize or to undertake previously enjoyable activities because of pain, exudate or because the appearance of the dressings was embarrassing for them.

Adapting and enduring is a strategy that is linked with dependency on the nurse or clinic for ongoing treatment, and to very limited knowledge of the condition and one’s options. In this study knowledge of the underlying condition was absent in all but one of the patients interviewed. The resulting position, according to Barofsky, 30 is a response to coercion. He views the continuum of patient activity in decision making as consisting of coercion, conformity and negotiation. In situations where there is inequality due to knowledge differences, or health states, the balance of power is such that one person is ‘more in control of the situation than the other’ (Barofsky, 11 p. 369) and as the weaker is ‘obligated to behave in a manner that he has had minimal input into determining’ he is coerced. To accommodate the treatment the patients deny their individuality and adjust their lifestyle: they accommodate uncomfortable and unsightly dressings, the nurses’ schedule for clinics or home visits for dressings, they even adjust their expectations regarding pain management and choose, because they believe they have no other choice, to live lives marked by pain at least for the duration of treatment. This behaviour is in many ways similar to the ‘sick role’ behaviours expected of patients with acute health problems who, having sought professional help, are then expected to cooperate and comply with treatment. Of course, in the early stage of going to the general practitioner with their wounds and their pain, the problem seemed just that, acute, and compliance was, they assumed, appropriate in the short term to restore them to normality. By the time they came to realize that they had a long‐term problem, the behaviour pattern was set.

Emphasizing the positive

Emphasizing the positive is a demonstration of the ability of the human spirit to transcend. This stage may arise out of adapting and enduring after the patients have suffered with their leg ulcers for months or even years. A typical response was: ‘Well, you can’t let them get you down, can you?’ or ‘You just have to get on with life, don’t you?’ or ‘Lots of people are worse off than me’. What has happened at this stage is of great importance because the patients show that they have learned to shift the focus of their lives away from the ulcer. They come to this shift in focus through their own reflection and restructuring of their lives: it is a process that nurses shape only by default and not through intention.

To reach this stage or this type of response, the patients have usually come to assess that the nurses and doctors have ‘Done the best they could’ and ‘tried everything’ but questioning indicates that in practical terms this means they have done their best with ulcer care, not pain management. The patients also show that they have reflected upon their general situation carefully and their health status in particular and have defined themselves as healthy people who happen to have problematic wounds. ‘I’m well. I’m not cut up or messed about like some people are, touch wood.’‘Oh I’m not ill. If my knees would let me go I’d get up and tear the place apart. I could go outside and do what I wanted to do.’

This response is an aspect of ‘creatively balancing resources for health’ which McWilliam et al., 31 who studied a sample of 13 elderly people with chronic illnesses, discuss and it is also found in Walshe’s32‘coping by being positive’ (p. 1098).

It is of interest that a contrast in perception is seen to exist here too between the nurses and the patients. A typical comment from the nurses is encapsulated in the following:

‘They’re not well because obviously they have got a circulation system problem, haven’t they? Initially anyway. So they’re patients who are going to have other complications as well.’

Negotiating for comfort

This is seen only in those patients who are able to develop, over time, a more equal relationship with their nurses. These patients, over the months taken to achieve healing or longer periods should ulceration recur, have learned to talk to their nurses and to engage them on a personal level so that they are seen as more rounded people and less as ‘patients’. These are the patients whom the nurses can relate information about, such as how by planning together they managed to achieve an acceptable cosmetic effect for a patient attending a wedding, or how they compromised the usual care approach on a special occasion.

Conclusion

Normalization is the goal of every patient with an acute or chronic illness. The professional management of the trajectory should enhance the probability of this being achieved as quickly and completely as possible. However, as this study has shown, when the trajectory being managed is that of an ulcer and not a person, there can be no real hope of successful integration of the chronic condition within the framework of the individual’s unique life. The initial medical consultation fails to define the pathology at the required condition‐specific level.

The custom and practice of referring any patient with a wound to the nurse for ongoing care essentially shunts him/her off into what Roth 33 referred to as a ‘chronic sidetrack’. The categorization of the patient’s problems as ‘wounds’ or as ‘leg ulcers’ symbolizes his/her ‘failure’ position in the health care system. Bliss, 34 a consultant physician in geriatric medicine, seems to be the only medical voice raised against this accepted pattern of care:

‘Why are most doctors content to allow nurses to carry out virtually the whole responsibility for skin wounds which they would not dream of doing for less severe, internal lesions? Is it because the skin is too easy to treat, or, perhaps more important, too easy to see? Or is it because it is too difficult and doctors have given up in despair?’

She argues that the existing dilemmas will only be resolved when doctors accept their responsibilities and act collaboratively with nurses to ensure that patients with chronic wounds are ‘properly assessed and reviewed’.

It would appear from this study that the situation for the patient will only improve when nurses gain greater awareness of the chronic illness perspective that venous hypertension requires. The focus on the wound leads to approaches that view pain as a diagnostic marker rather than as a symptom that merits equal consideration in the holistic care of the person. While it is undeniable that the majority of patients can achieve healing of their wounds in a matter of a few months, 35 , 36 recurrence rates remain worryingly high,37 and it is unfortunately the case that some patients do not heal for a variety of reasons. 38 , 39 , 40 Patients with venous hypertension need nurses who can deliver ‘supportive assistance’ as Corbin and Strauss41 define it, i.e. having skills not simply in direct care but also in helping them to meet their biographical needs and perform the everyday activities that affect quality of life.

When a patient has a chronic illness, that patient should be the navigator of his/her health trajectory, seeking piloting assistance from others for those periods of crisis, when acute symptoms overcome the normal course of events. It would be interesting to compare the experiences of patients in England with those in other countries, such as Australia, where the very distance between some patients and their health care providers may be so great as to prevent the pattern of care seen here from developing. This point raises interesting issues about the limitations of this study. The groups included are those routinely found within the NHS system of England and the study is grounded in those data alone. Further research will hopefully result from the widespread current interest in tissue viability and the availability of advanced educational preparation through diploma and degree modules and the newer approaches to care that these might generate.

Living with a chronic illness is not a matter of dealing with acute episodes scattered into an otherwise normal life but rather, a matter of total readjustment of an individual’s life to accommodate illness and its management within a biography. Successful management of care for these patients is only possible when it is based upon an understanding of the reciprocal impact of the illness and disease management.

References

- 1. Glaser B & Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1967.

- 2. Thorne SE & Robinson CA. Health care relationships: the chronic illness perspective. Research in Nursing and Health, 1988; 11 : 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pott E. Health Promotion and Chronic Illness: Discovering a New Quality of Health Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992.

- 4. Kleinman A. The Illness Narratives. Suffering, Healing and the Human Condition New York: Basic Books, 1988.

- 5. Husband LL. The management of the client with a leg ulcer: precarious nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1996; 24 : 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Benner P & Wrubel J. The Primacy of Caring Stress and Coping in Health and Illness Menlo Park, California: Addison‐Wesley, 1989.

- 7. Bury M. Meanings at risk: the experience of arthritis. In: Anderson R, Bury M (eds) Living with Chronic Illness: the Experiences of Patients and Their Families. London: Unwin Hyman, 1988: 89–115.

- 8. Chenitz WC & Swanson JM. From Practice to Grounded Theory, Qualitative Research in Nursing Menlo Park, California: Addison‐Wesley, 1986.

- 9. GlaSeries BG. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis Mill Valley, California: Sociology Press, 1992.

- 10. Dean K. Self care responses to illness: a selected review. Social Science and Medicine, 1981; 15A : 673–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dean K. Lay care in illness. Social Science and Medicine, 1986; 22 : 275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chasse MA. The experiences of women having a hysterectomy. In: Morse JM, Jonson J (eds) The Illness Experience. Newbury Park: Sage, 1991: 89–139.

- 13. Strauss A, Fagerhaugh S, Suczek B, Weiner C. The Social Organisation of Medical Work Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

- 14. Browse NIKG & Burnand Thomas ML. Diseases of the Veins Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment London: Edward Arnold, 1988.

- 15. Schofield OMV & Hunter JAA. Diseases of the skin. In: Haslett C, Chilvers ER, Hunter JAA, Boon NA (eds) Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine, 18th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999: 877–921.

- 16. Tumman J & Coggins R. A case of mistaken identity: primary cutaneous lymphoma presenting as venous ulceration. Hospital Medicine, 1999; 60 : 761–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bowman PH & Hogan DJ. Leg ulcers: a common health problem with sometimes uncommon etiologies. Geriatrics, 1999; 54 : 47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Negus D & Friedgood A. The effective management of venous ulceration. British Journal of Surgery, 1983; 70 : 623–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sethia KK & Darke SG. Long saphenous incompetence as a cause of venous ulceration. British Journal of Surgery, 1984; 71 : 754–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Negus D. Leg ulcers. A Practical Guide to Management London: Butterworth‐Heineman, 1995.

- 21. Corbin J & Strauss A. A nursing model for chronic illness management based upon the trajectory framework. In: Woog P (eds) The Chronic Illness Trajectory Framework: the Corbin and Strauss Nursing Model. New York: Springer, 1992: 9–28.

- 24. Gross EA, Wood CR, Lazarus GS, Margolis DJ. Venous leg ulcers: an analysis of underlying venous disease. British Journal of Dermatology, 1993; 129 : 270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burton CS. Treatment of leg ulcers. Dermatology Clinics, 1993; 11 : 315–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walshe C. Living with a venous leg ulcer: a descriptive study of patients’ experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1995; 22 : 1092–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hamer C, Cullum NA, Roe BH. Patients perceptions of chronic leg ulcers. Journal of Wound Care Management, 1995; 3 : 99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mallett L. Controlling the pain of venous ulceration. Professional Nurse, 1999; 15 : 131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Roe BH, Luker KA, Cullam NA, Griffith JM, Kenrick M. Assessment, prevention and monitoring of chronic leg ulcers in the community: a report of a survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 1993; 2 : 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barofsky I. Compliance, adherence and the Therapeutic Alliance: steps in the development of self‐care. Social Science and Medicine, 1978; 12 : 369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McWilliam CL, Stewart M, Brown JB, Desai K, Coderre P. Creating health with chronic illness. Advances in Nursing Science, 1996; 18 (3): 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roth JA. Timetables: Structuring the Passage of Time in Hospital Treatment and Other Careers New York: Bobbs‐Merrill, 1963.

- 34. Bliss M. Wound management and the elderly patient. Care of the Elderly, 1990; 2 : 185–188. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moffatt CJ, Franks P, Oldroyd M et al Community clinics for leg ulcers and impact on healing. British Medical Journal, 1992; 305 : 1389–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O'Hare L. Implementing district‐wide nurse‐led venous leg ulcer clinics: a quality approach. Journal of Wound Care, 1994; 3 : 389–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tuxhill W & Kenmore P. Leg work. Health Service Journal, 1992; 102 : 26–26. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bliss M & Scholfield M. A pilot leg ulcer clinic in a geriatric day hospital. Age and Ageing, 1993; 22 : 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Erickson CA, Lanza DJ, Karp DL et al Healing of venous ulcers in an ambulatory care program: the roles of chronic venous insufficiency and patient compliance. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 1995; 22 : 629–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]