Abstract

Health care consumerism is a movement concerned with patients’ interests in health care, crucially those that are repressed or partly repressed by dominant interest‐holders. Like feminism, health care consumerism attracts dislike and confusion as well as enthusiasm. But just as the voicing of women’s repressed interests leads to their gradual acceptance by dominant interest‐holders, so does the voicing of patients’ repressed interests.

Keywords: feminism, health care consumerism, repressed interests

‘Generally speaking, the use of the word confusion by one participant in the political process usually means there is conflict over goals…’ 1

Introduction

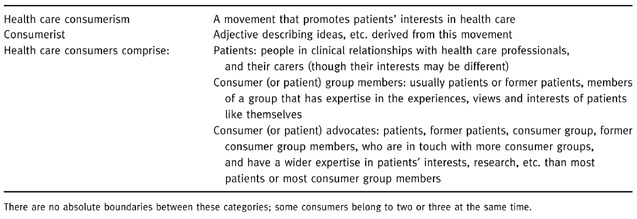

Health care consumerism is cradled in confusion. Few patients or health professionals could say exactly what it is, but many health professionals say they want less of it. 2 They believe that health care consumerism encourages patients to demand health care so selfishly that community bonds, consensus and harmony will be destroyed. 3 , 4 Conversely, consumer advocates, consumer groups and some patients (Table 1), 5 believe that health care consumerism is essential if health care is to become more effective and more humane. They commit themselves to a cause they believe is ethically imperative.

Table 1.

Terms used for the consumer side of health care

Confusion often points to underlying and unexpressed discord about power. Many consumer groups and organizations state that they are concerned with patients’ interests, giving their goals as the identification or promotion or protection or representation or advocacy of those interests. 6 , 7, –8 Broadly, health care consumerism can be said to be a political movement that promotes patients’ interests, joining with health professionals when they act in patients’ interests as patients define them but opposing them when they act against, or repress, patients’ interests. But interests is a complex concept, 9 bringing in its train the concept of power; the power to secure the meeting of the interests identified. Thus health care consumerism seeks a partial redistribution of power between health professionals and patients. By power here I mean ‘the ability to take one’s place in whatever discourse is essential to action and the right to have one’s part matter’. 10 This is an important definition. It is partly an ethical statement, partly a political one. It helps us see that the repression of patients’ interests is brought about and sustained through the impairment of that ability and the denial of that right. It is a definition that, once understood, is ultimately consistent with medicine’s own high ethical principles. It is thus a benign definition of power, drawing patients and health professionals together, albeit in a new relationship.

This benignity is related to five conditions that make health care consumerism in developed countries with western systems of health care a special, although not unique movement:

• patients and health professionals live in close and usually amicable relationships with each other: the professional‐patient relationship;

• health professionals believe in good faith that they act in the interests of patients or that there is little difference between their respective interests;

• patients at first accept these beliefs but eventually begin to discover and define their own interests and find their own voice;

• individual patients, consumer groups and consumer advocates adopt different constellations of thought and belief from amongst a range of ideological positions, according to the particular culture they are part of and their personal experiences of health care;

• health professionals eventually begin to hear and to accept the definitions of patients and of consumer groups.

These five conditions foster the potential for mutual understanding and accommodation between the patient and the professional‐sides of health care; at any one time there is potential for harmony as well as for discord in patient‐professional clinical and working relationships. But patients’ definitions of their own interests and health professionals’ acceptance of those definitions both call for protracted effort: and both can experience anger or anguish. Consumer advocates feel their task is unending; health professionals feel under constant threat of criticism, however conscientious their practice. Until power is more nearly equal on both sides of health care and at every level of discourse, these troubled feelings are likely to remain.

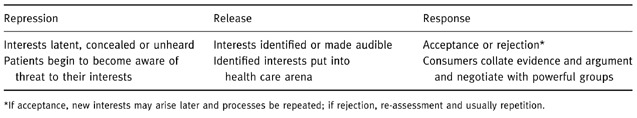

Table 2 represents a model of health care consumerism from this perspective. A model is a way of organizing our thoughts to help us understand the way things are or ‘reality’. Health care consumerism is complex because it does not involve only the patient‐consumer side of health care: health professionals sometimes voice patients’ repressed interests; 9 and they always affect, together with other socio‐political factors, the direction and rate at which the movement develops. In the USA, for example, lucidity, the right of patients to know all relevant details about the situation in which they find themselves, has long been an imperative of medical ethics. 11 So patients do not have to worry as much about the truthfulness of their doctors as they do in the UK. 12 In the Netherlands, consumer groups have to be consulted when health professionals draw up sets of standards for practice. 13 So consumer groups do not have to struggle for legitimacy. 5 The model has to capture though simplify this complexity and diversity. In it, repression refers to the repression or partial repression of patients’ interests; release to their identification and articulation (mainly) by patients, consumer groups and consumer advocates; and response to the acceptance or rejection of those definitions of interests by health professionals.

Table 2.

The repression: release: response model

Some other political movements resemble health care consumerism in its general goal of release from repression; anti‐slavery and anti‐racism are examples. But a closer example is feminism because all five of the conditions noted above apply to it, the groups being women and men. Because feminism is also more familiar to most people than health care consumerism, I shall make some detailed comparisons between it and health care consumerism to help our understanding of the latter. 9 After discussing the three components of the model, repression, release and response, I shall touch on the direct links between health care consumerism and feminism and conclude with a final comparison between their goals.

Repression

When people become patients, they enter a world created by health professionals, especially by doctors, that reflects doctors’ values, needs, perceptions and interests, just as women enter a world created by men. 14 Doctors’ and men’s dominant interests in these worlds are sustained by other groups’ beliefs, actions and social arrangements (‘structures’) 1 as well as by dominant interest‐holders’ own actions. Such dominance both leads to and reflects the repression of weaker groups’ interests. Repression as a political term means keeping back, suppressing or withholding something. 15 Dominance enables dominant interest‐holders to prevent weaker interest‐holders from being included in the discourses essential to action; to restrict their ability to take part even when they are included; and even when they are included, to deny that their part matters.

Thus men for generations governed western countries without women’s votes or women members of parliament; and the medical profession still largely regulates itself. 16 Where there are lay members of professional regulatory bodies, many are just that – lay, with no specific expertise in or alignment with the patient‐side of health care. Although patients, consumer group members and consumer advocates are increasingly included in professional groups discussing professional performance, clinical standards and other matters hitherto regarded as purely professional, 5 many professional groups still exclude such members. Even when they are included, they are usually only in a small minority. Most of the time, matters affecting patients’ collective interests are discussed in their absence, just as men are still making decisions that affect women without ensuring that women take part in the decision‐making. 17

Similarly, individual patients are seldom invited to join in multi‐disciplinary discussions about their own treatment and care. Yet some patients can find going over their own case, asking questions and making choices with a team of specialists helpful. 18

Exclusions give pragmatic advantages to the stronger interest‐holders. Pragmatic advantages are always justified by matching ideologies, sets of sincerely held convictions. Men used to believe that women had inferior intellectual and moral characters. 19 Many health professionals believe that patients cannot contribute much of value to discussions. They still believe, for example, that patients cannot judge clinical competence or the technical quality of care, even though there is evidence that they can. 20

Dominance is also sustained ideologically by dominant interest‐holders’ belief that their own interests are the same as those of the weaker group. Or dominant interest‐holders believe that they act in repressed interest‐holders’ interests or best interests. The distinction between these beliefs is not always clear. But few western men would now claim to act in women’s interests; or at any rate, men’s conviction that men’s and women’s interests and opportunities are the same is the more commonly expressed. Health professionals, however, often express their conviction that they act in patients’ interests or best interests; it is a major part of professional ideology. 16

Health professionals’ ideology of best interests can sometimes protect patients; provided that patient and health professional have agreed what those best interests are, health professionals’ greater power enables them to act on patients’ behalf. But the ideology can also harm patients. It can foster a more subtle form of exclusion from the discourses essential to action than simply excluding them physically. It is easy to impair patients’ ability to take part in discourses that affect them by keeping them unaware of factors that might threaten their interests. It is easy to offer them only part of what they need to know.

Writing a ‘do not resuscitate’ order without competent patients’ knowledge; 21 not offering patients information that might affect their acceptance of a specific diagnostic 22 or therapeutic procedure; 23 entering patients into clinical trials without their consent; 24 withholding information about treatments available elsewhere 25 are familiar examples.

Alternatively, patients can be present at discourses essential to action – particularly when they initiate such discourses themselves – but find that their part does not matter. What patients say or ask is not heeded if it contradicts health professionals’ view of what is best for patients. Midwives used to refuse parents’ requests to see their stillborn baby. 26 Doctors may block a patient’s or a relative’s request for a second opinion, even when there is a dispute about treatment. 27 Patients’ questions about diagnosis or prognosis are brushed aside. 28

These kinds of threat to patients’ interests, through the minimization of their part in the discourse, can lead to unassuageable losses of trust. 28 The boundaries between health professionals’ sincerely held beliefs and health professionals’ practical convenience or lack of appropriate skills 29 are often obscure and tend to be mutually reinforcing. Moreover, one person’s good motives can become another person’s harm. For that reason, some consumer advocates are wary not only of health professionals’ best interests ideology but also of their ethical value, beneficence. Yet beneficence probably contributes to the good feeling that helps health professionals eventually accept patients’ own definitions of their interests.

Another contribution to good feeling lies in the nature of structural interests and their ideological support. Structural interests are so pervasively part of the status quo that they are not usually felt personally. Doctors can be dedicated to their patients’ welfare and behave with altruism and generosity, just as men can act well towards women they know. Consumer advocates can fall ill and consult their doctor confidently, just as feminists can fall in love and marry happily. Patients, consumer groups and consumer advocates, like women and feminists, appreciate the skills, the expertise and the goodwill that most health professionals or men show. Cordial feelings towards health professionals or towards men can coexist with anger about specific disadvantages experienced by patients or by women.

Release

At first, and this may last for several hundred years, dominant interest‐holders’ interests and ideologies are accepted without analysis or question; that is what dominance means. It is only after subordinate groups find a voice that dominant ideologies begin to be challenged. New definitions of interests are set free from the constraints of silence and lack of social support. Then the new consciousness becomes irreversible; the issues voiced change over time but the voice does not.

This history, familiar from feminism, appears to fit health care consumerism exactly. Patients express distress or concern about specific practices or standards they have experienced; they form groups (consumer groups); some patients or consumer group members develop a wider expertise in patients’ interests (consumer advocates); and health care consumerism is born.

Response

The conceptual release of an interest from repression, the bringing of it to the consciousness of other patients and of other groups, seldom of itself leads to changes in professional policies and practices. The processes of response are complex and cannot be analysed here. But a description of some points that bear on response is useful for understanding health care consumerism at its present stages of development.

Consumer advocates and feminists generally work to secure collective policies and practices that benefit individual patients or individual women by enabling them to act in their own interests as they see them, within the limitations of current knowledge, social and cultural acceptability and the law. To have an interest in something is to have a stake in it. 15 Patients have a unique stake in their health care; it can affect the rest of their lives, their life plans and life stories, 30 their fears and values, their responsibilities towards themselves and their families, and themselves as moral agents. 31 Interests are not just wants or preferences; they almost always involve weighing benefits and risks. 32 How these are weighed is highly individual. So consumer groups and consumer advocates incline to believe that patients should be able, if they wish, to consult their beliefs and priorities, as well as whatever evidence there is, and their doctor’s experience and advice, in arriving with their doctor at a course of action. 33 It should never be the aim of health care consumerism (or of feminism) to replace the professional repression of patients’ (or women’s) interests by consumerist (or feminist) repression.

Again, some comparisons: securing the vote for women lets them use it or not use it. Gaining access for women to universities lets those who can qualify attend. Unrestricted hospital visiting times lets patients have the support of their relatives and friends when they most need that support. Offering patients choice of treatment lets individual patients make a choice or delegate that choice to their doctor. The benefits for patients that health care consumerism seeks are those that help patients take their places in the discourses essential to action and that ensure that any action taken will be to proper standards of provision and professional competence.

In this enterprise, consumer advocates’ relation to patients is the same as feminists relation to women. Consumer advocates put forward the views and experiences of patients, when they know what those are. In doing that they should be able to draw on a wider knowledge of those experiences and views than most individual patients have. 5 Grounded in patients’ experiences and interpretations of health care, 6 consumer advocates can take a more comprehensive and coherent view of patients’ interests than most individual patients can, just as feminists’ definitions of women’s interests are more comprehensive than those of most women but are drawn from women’s experiences and predicaments. Individual patients may or may not share particular consumerist views. But once consumer advocates and consumer groups have contributed to bringing about change in the direction of greater freedom for patients to act in their own interests, individual patients accept the benefits of those changes as a matter of course. They become part of their expectations of good health care.

Although health care consumerism challenges professional policies and practices when they conflict with patients’ interests as patients see them, it supports policies and practices that are compatible with patients’ interests. The interplay of interests is complex. On the whole, men and the health professions move, however slowly, in the directions that feminists and consumer advocates, respectively, desire. Policies and practices that disadvantage women or patients are modified or eliminated. New standards, statements of how things should be done, are written into legislation, employment policies, organizational standards, clinical, ethical and research guidelines. What was once radical and controversial becomes the status quo. Younger generations of women may forget their grandmothers’ struggles. New patients are not conscious of what they owe to the first consumer groups. Many health professionals are unaware that some practices, now part of their routine practice, had once to be fought for by consumer advocates.

Change, inevitably, throws up new convergences and conflicts of interest, new re‐definitions. New government policies, new technologies and clinical advances create new interests, interests that were not there before. 34 Some of the new interests of dominant interest‐holders may affect patients’ interests repressively. In addition, meeting old interests can uncover or even create new interests. Although women can now attend universities, the proportion of eligible women awarded fellowships in biomedical research in Sweden is lower than that of men. 35 In Britain 28 years of pressure from the consumer group, the National Association for the Welfare of Children in Hospital, had secured unrestricted access to their parents for children in children’s wards by 1989. 36 But even now, not all children can have their parents’ comfort during induction and recovery from anaesthesia. 37 Yet as a consequence of different parental concerns and consumer groups’ pressures, in Britain relatively more children have a parent with them for induction and in USA for recovery. 38

Thus the status quo at any specific time and place is a combination of the assumptions, perceptions, values and practices that are taken for granted unexamined by all or most professionals, patients, consumer groups and consumer advocates; issues over which there is conflict; and issues over which conflict has been resolved.

In the UK, patients, consumer groups and consumer advocates usually have to react to professional policies and practices; they seldom take part in their formulation in the first place 39 , 40 – they are absent from the initial discourse essential to action. This is beginning to change through, for example, the patient liaison groups of the royal medical colleges, where consumer advocates have an opportunity to initiate discussion of new topics, 5 or through the consultation processes of the General Medical Council. 41 But some other countries are further forward. In the Netherlands, consumers are included in decision‐making processes more systematically; setting standards is not regarded as the prerogative of the professions. 42 But at whatever points conflict between the views of consumers and health professionals becomes evident, it has to be resolved by changes in dominant interest‐holders’ position; changes in consumers’ position in the light of professional explanations; or the discrediting of a particular professional or consumerist position. These processes may take place quickly or slowly, completely or with parts of issues left unresolved. Sometimes the law or the government step in with new statutory obligations or new interpretations of rights.

These dynamics, these interplays of convergent and conflicting interests, of old interests and new emerging ones, of release and response, are reflected in the ideological positions and social relations amongst people on the patient side, amongst people on the professional side, and between each.

Consumer advocates and consumer groups, like individual feminists and feminist groups, vary in the issues they address and organize their expertise around. They also vary in how radical they are, in how and how far they challenge dominant practices, ideologies and ethics. 43 There are at least nine distinct constellations of feminist thought and belief about how the subordination of women’s interests to men’s came about, is sustained and could be overcome; they include liberal, Marxist, radical, psychoanalytic, socialist, existentialist, and post‐modern theories. 44 Ideologies in health care consumerism are less well developed and distinct, although some of the ideas above could be drawn on to explain why health care consumerism has developed when and how it has – for example, the challenge of postmodernism to biomedical knowledge and power. 45

Whatever their ideologies, the principles that guide and justify their actions, pragmatic variations in health care consumerism can be seen in different kinds of consumer groups. Self‐help or support groups, activist or pressure groups, advocacy groups and community groups concerned about local health care vary in their declared purposes, although they tend to overlap in their blending of emotional and ideological support for their own members with wider advocacy for the interests of other patients. 43 Consumer groups also vary in their composition and style of working: they may be patient‐led; professionally dominated; or commercially dominated, usually by drug companies. 46 Thus radical, patient‐led groups like the Association for Improvements in the Maternity Services (AIMS) or Radiotherapy Action Exposure Group (RAGE) challenge clinical and ethical practice repeatedly. Less radical groups like the National Childbirth Trust (NCT) or Action for Sick Children tend to be more emollient. And conservative groups, often professionally led, like the British Diabetic Association (BDA) or the Multiple Sclerosis Society (MS) support professional definitions of patients’ interests so thoroughly that more radical factions, the Insulin Dependent Diabetes Trust (IDDT) and the Association for Research into Multiple Sclerosis (ARMS), have split from them. 46 , 47

As with feminist groups and factions, differences in ideology and approach tend to turn into personal criticism: so‐and‐so is too easily seduced by health professionals; so‐and‐so is too aggressive towards them. Strong feelings characterize those who work for disadvantaged interest‐holders. These feelings can be exacerbated by the vested interests that develop as the movement, and its diverse components, grows and attracts attention from professional groups, the government, etc. There are tensions between those paid for working for consumer groups and those working at financial cost to themselves. There are tensions between those who have experienced health care for the index disease or condition and those who have not – patients vs. former patients, carers and those not personally involved. Academics and researchers with consumerist leanings form yet another interest group, partly overlapping, partly competing with the others. All this adds to variability of position and practice.

At the same time, health professionals vary in the extent to which they sympathize with consumerist views and aspirations. Feminists call men who understand and accept feminist positions ‘men of goodwill’. 48 The corresponding term in health care consumerism is the ‘good professional’. 9 This value judgement is more than an expression of bias; it points to something important. Health professionals who support consumerist views are often at the forefront of their profession, open to new ideas and practices, and able to evaluate them against professional ideals. The health professions’, especially medicine’s, high ethical aspirations and concern for patients’ welfare are compatible with health care consumerism. In that sense, health care consumerism and professionalism are complementary, not antagonistic.

Some variation, moreover, in ideology and experience on both the consumerist and professional sides is helpful. It enables individual health professionals and individual patients, consumer group members and consumer advocates to align their views with each other’s. The consequent marriages of professional and consumerist views helps hold both together in amity. Shifting alliances of views allow consumer advocates or consumer groups and health professionals to work together towards the successful resolution of controversial issues. 5 Health professionals who accept consumerist points can influence their peers. Acting from a position of disadvantage, as patients, consumer groups and consumer advocates do, this is crucial. It is akin to feminists’ need to get their definitions of women’s interests accepted by at least some influential men. As long as women and men, patients and health professionals are unequal in the discourses essential to action, then varying approaches, different shades of belief and interpretations of evidence, are constructive as well as inevitable.

Health care consumerism and feminism

There is evidence that women tend to receive less good health care than men. They may be treated more tardily and less thoroughly than men with the same condition, e.g. heart disease. 49 Their exclusion from some clinical trials means that more is known about what would benefit men than women, e.g. aspirin for the primary prevention of heart disease. 50 For conditions peculiar to women, some women feel that treatments are too harsh, too radical, too interventionist, reflecting indifference to their long‐term welfare as women. 51 Women have worse access to doctors of their own gender than have men 52 and may feel they are patronized, dismissed or demeaned by men doctors. Women can therefore be said to suffer a double disadvantage in health care: that they share with male patients and that which reflects and reinforces the more general discrimination against them.

So it is unsurprising that feminists have played a prominent part in criticizing medical practice, past and present, 53 and medical ethics. 54 At the same time, women have played a major part in setting up activist consumer groups, not just for health care peculiar to women but for the health care they share with men. Again, there is a double aspect: women’s experiences have provided the bases for feminist analyses; feminist critiques have helped alert women to their disadvantages in health care. Probably most consumer advocates are women, just as most feminists are; and the two are sometimes found in the same person.

Conclusion

Just as many men and some women do not find feminism credible or try to understand the evidence and arguments upon which its tenets are based, so some health professionals and some patients dismiss health care consumerism. But there is one last comparison. Most feminists do not want to reverse the conditions under which women have suffered. They want women to have equality of voice, of esteem and of power, not that men’s voices shall be silenced and their masculinity annihilated. 55 Consumer advocates do not want to discredit the professionalism on which health professionals build their identities. They do not want health professionals to loose their skills, their expertise or their sense of self‐worth. Equal and complementary is an easy slogan for women and men, patients and health professionals. But easy slogans can express profound ethical aspirations, however, hard and long their attainment.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Elisabeth Hartley, Eileen O’Keefe and the referees for their helpful comments.

References

- 1. Alford RR. Health Care Politics, Ideological and Interest Group Barriers to Reform Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1975.

- 2. Stott N, Boland M, Hayden J, et al. The Nature of General Medical Practice London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 1996.

- 3. Dunstan ER. Ideology, Ethics and Practice, the Second John Hunt Memorial Lecture, 8 September, 1994 London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 1994.

- 4. Toon P. What Is Good General Practice? London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Williamson C. The rise of doctor‐patient working groups. British Medical Journal, 1998; 317 : 1374 1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Association of Community Health Councils for England and Wales . Resolutions at AGM 8–10 July, 1997 London: Association of Community Health Councils for England and Wales, 1997.

- 7. The Patients Association . Patient Voice, 1996; 70 : 16 16. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Europa Donna . Movimento d’opinione contro i tumori del seno. Milan: Europa Donna, 1998.

- 9. Williamson C. Whose Standards? Consumer and Professional Standards in Health Care Buckingham: Open University Press, 1992.

- 10. Heilbrun CG. Writing a Woman’s Life New York: WW Norton, 1988.

- 11. Fried C. Medical Experimentation and Social Policy Amsterdam: North Holland, 1974.

- 12. Royal College of General Practitioners . You and Your GP During the Day. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 1997.

- 13. Netherlands Ministry of Welfare Health and Cultural Affairs . The Quality of Care in the Netherlands Rijswijk, the Netherlands: Ministry of Welfare, Health and Cultural Affairs, 1992. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14. Rich A. Blood, Bread and Poetry, Selected Prose, 1979–85 New York: Norton, 1986.

- 15. Onions CT (ed). Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1933.

- 16. Irvine D. The performance of doctors. I: Professionalism and self‐regulation in a changing world. British Medical Journal, 1997; 514 : 1540 1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ryan A. Letter, The Times, 31 August, 1998, p.21, col 5.

- 18. Spingarn MD. Patient‐doctor partnering: breaking out of the mold. The Patient’s Network, 1997; 2 : 18 19. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trilling L. The Opposing Self London: Secker and Warburg, 1955.

- 20. Hogg C. Partnership in Practice, Involving Patients and the Community London: National Consumer Council, 1994.

- 21. Macklin R. Enemies of Patients New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- 22. Venn‐Treloar J. Nuchal translucency – screening without consent. British Medical Journal, 1998; 313 : 1027 1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Silvestis G, Pritchard R, Welch HG. Preferences for chemotherapy in patients with advanced non‐small lung cancer: descriptive study based on scripted interviews. British Medical Journal, 1998; 317 : 771 775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goodare H. Studies that do not have informed consent from participants should not be published. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316 : 1004 1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Entwistle VA & Watt IS. Disseminating information about healthcare effectiveness: a survey of consumer health information services. Quality in Health Care, 1998; 7 : 124 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flint C. Sensitive Midwifery London: Heinemann, 1986.

- 27. Anonymous, Pelosi AJ, McGinnis EB, Elliott C, Douglas A. Second opinions: a right or a concession? British Medical Journal, 1995; 311 : 670 672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blennerhassett M. Truth, the first casualty. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316 : 1890 1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tattersall M & Ellis P. Communication is a vital part of care. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316 : 1891 1892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brody H. Stories of Sickness. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

- 31. Alderson P, Madden M, Oakley A, Wilkins R. Women’s views of breast cancer treatment and research. Report of a Pilot Project, 1993 London: University of London, Social Science Research Unit, 1994.

- 32. Lowrance WW. Healthcare Risks for Health Benefits. The Economist, 1998; 349 : 8086 8086. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Quill TE & Brody H. Physician recommendations and patient autonomy: finding a balance between physician power and patient choice. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1996; 125 : 763 769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schwarz M & Thompson M. Divided We Stand, Redefining Politics, Technology and Social Choice Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1990.

- 35. Wenneras C & Wold A. Nepotism and sexism in peer review. Nature, 1997; 387 : 341 343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shelley P. Keypoints 4, Children in Hospital: Parents’ Rights London: Action for Sick Children, 1991.

- 37. Hall PA, Payne JF, Stack CG, et al. Parents in the recovery room: survey of parental and staff attitudes. British Medical Journal, 1995; 310 : 163 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Anonymous, Parent Presence . Paediatric Mental Health, 1998; 17 : 6 6. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chadderton H. An analysis of the concept of participation within the context of health service planning. Journal of Nursing Management, 1995; 3 : 221 228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Neuberger J. Patients’ priorities. British Medical Journal, 1998; 317 : 260 262. 9677218 [Google Scholar]

- 41. General Medical Council . Council Agenda Paper. 3–4 November, 1998 London: General Medical Council, 1998.

- 42. Government Committee on Choices in Health Care . Choices in Health Care. Rijswijk, The Netherlands: Ministry of Welfare, Health and Cultural Affairs, 1992. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43. Borkman T. A selective look at self‐help groups in the United States. Health and Social Care in the Community, 1997; 5 : 356 364. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tong R. Feminist Thought, a Comprehensive Introduction Boulder and San Francisco: Westview Press, 1989.

- 45. Mitchell D. Postmodernism, health and illness. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1996; 23 : 260 262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hogg C. Patients, Power and Politics: Health Policy from a User Perspective. London: Sage, (in press).

- 47. Gillies L. Who sets the research agenda? CERES (Consumers for Ethics in Research) News, 1998; 24 : 1 3. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tong R. Feminist Approaches to Bioethics Cumnor Hill, Oxford: Westview Press, 1997.

- 49. Sharp I. Gender issues in the prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease. In: Doyle L. (ed) Women and Health Services. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1998.

- 50. Josefson D. US expands prescribing recommendations for aspirin. British Medical Journal, 1998; 317 : 1176 1176. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Campaign Against Hysterectomy and Unnecessary Operations on Women . Proposal for a Women’s Medical Protection Act Woking, Surrey: 1997.

- 52. Day P. Women Doctors, Choices and Constraints in Policies for Medical Manpower London: King’s Fund Centre, 1982.

- 53. Ehrenreich B & English D. For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1978.

- 54. Sherwin S. No Longer Patient, Feminist Ethics and Health Care Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992.

- 55. Heilbron CG. Hamlet’s Mother and Other Women New York: Ballentine Books, 1990.