Abstract

Objective

To look at how communication by health professionals about infant feeding is perceived by first time mothers.

Design

Qualitative semi‐structured interviews early in pregnancy and 6–10 weeks after birth.

Subjects and setting

Twenty‐one white, low income women expecting their first baby were interviewed mostly at home, often with their partner or a relative.

Results

The personal and practical aspects of infant feeding which were important to women were seldom discussed in detail in ante‐natal interviews. In post‐natal interviews women described how words alone encouraging them to breastfeed were insufficient. Apprenticeship style learning of practical skills was valued, particularly time patiently spent watching them feed their baby. Women preferred to be shown skills rather than be told how to do them. Some felt pressure to breastfeed and bottle feeding mothers on post‐natal wards felt neglected in comparison. Women preferred their own decision‐making to be facilitated rather than being advised what to do. Some women experienced distress exposing their breasts and being touched by health professionals. Continuity of care and forming a personal relationship with a health professional who could reassure them were key factors associated with satisfaction with infant feeding communication.

Conclusions

The infant feeding goal for many women is a contented, thriving baby. In contrast, women perceive that the goal for health professionals is the continuation of breastfeeding. These differing goals can give rise to dissatisfaction with communication which is often seen as ‘breastfeeding centred’ rather than ‘woman centred.’ Words alone offering support for breastfeeding were often inadequate and women valued practical demonstrations and being shown how to feed their baby. Spending time with a caring midwife with whom the woman had developed a personal, continuing relationship was highly valued. Women were keen to maintain ownership, control and responsibility for their own decision‐making about infant feeding.

Keywords: breast feeding, communication, discourse analysis, infant feeding, post‐natal care, qualitative research

Introduction

Breastfeeding rates in Britain have changed little since 1980. 1 , 2 Women report conflicting advice about infant feeding, inadequate support, and care that is inflexible and insensitive to individual needs. 3 , 4, –5 The Audit Commission found that more negative comments are made by women about post‐natal care than other aspects of childbirth. 6 Support for women learning to breastfeed is important 7 and continuity of care improves satisfaction with post‐natal care in general. 8 However, there has been little research looking at how women perceive communication about infant feeding, which is an important component of support.

We have argued elsewhere that the decision to initiate breastfeeding and the confidence and commitment to persevere is influenced more by embodied knowledge gained from seeing breastfeeding rather than theoretical knowledge. 9 , 10 An apprenticeship model to ante‐natal preparation and learning a new behaviour like breastfeeding seems to meet women’s needs best. This paper builds on these findings and examines in more detail women’s discourse when describing communication scenarios with health professionals. In this paper the term ‘health professionals’ refers to midwives, health visitors, doctors and advisers from voluntary organizations. In particular we look at whether women with embodied knowledge gained through seeing a friend or relative breastfeeding differ in their post‐natal accounts of communication with health professionals from women who have only seen breastfeeding at a distance.

Subjects and methods

Twenty‐one white, lower social class and low educational level, primigravida women living in a deprived inner London Health Authority were selected for investigation as they belong to a group known to have low breastfeeding rates. They were recruited by general practitioners and midwives known to the researcher (PH) and interviewed by PH prior to ante‐natal booking where possible. Nineteen were re‐interviewed 6–10 weeks after birth. Two women had moved away. PH introduced herself as a researcher, not a doctor and explained that the research was about choices women make looking after their first baby. This enabled infant feeding to be discussed in the wider context of pregnancy and family life according to the woman’s own priorities. The infant feeding agenda was declared during the ante‐natal interview. Ethics committee approval was obtained.

Recruitment

Contrary to expectations, women initially recruited were older and intending to breastfeed, so purposeful sampling 11 was used to target teenage women intending to formula feed to ensure that all viewpoints were represented. Eight women recruited knew that PH was a doctor, but were not her patients. The influence of the role of PH as a researcher and a general practitioner on both the recruitment and the interview data has been reported elsewhere. 12 Recruitment ceased when theoretical saturation 13 had been reached.

Interviewing

Data was collected using a topic guide developed during four pilot interviews rather than using a structured questionnaire, to enable respondents to tell their stories in their own way. Women chose the time and place of interview (all except three took place at home) and whether to be interviewed alone or with another person of their choice (nine partners, three mothers, one father and two sisters were present). Interviews were tape‐recorded, fully transcribed and field notes of reflexive observations were recorded in a research diary.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection and analysis proceeded in an iterative manner, in accordance with grounded theory. 14 This allowed concepts to be confirmed, rejected or modified as the study progressed. The Framework method of data analysis 15 was applied systematically both within and across cases using categories and themes identified by reading the transcripts. A coding index was developed and applied to each transcript using Microsoft Word computer software. Ante‐natal and post‐natal matrices of the coded themes were created for five feeding intention groups. These matrices consisted of the women grouped according to feeding intention group along the vertical axis and the coding index across the horizontal axis. Extracts of the data were entered into the boxes of the matrices, with cross reference to the interview transcript page. Post‐natal matrices were also created using women grouped according to the six feeding outcome groups along the vertical axis. This enabled patterns and associations to be identified according to both feeding intention and outcome. The language used by women when recounting communication scenarios with health professionals was examined in detail using the principles of discourse analysis. 16 The use of words like ‘show’, ‘advise’, ‘tell’, ‘reassure’ and ‘help’ were compared between feeding outcome groups.

Validation and trustworthiness

Respondent validation was used to check whether the data analysis and interpretation truly represented women’s views. The 19 women remaining in the study were sent a synopsis of their individual case analysis, together with a summary of the key research findings. Confirmatory feedback was received from 11 women with two letters being returned undelivered. The emerging analysis was cross‐checked using data obtained from different sources (individuals and couples). Both authors were involved in reading and analysing transcripts. A more detailed account of the methodology and findings of this study is available. 17

Results

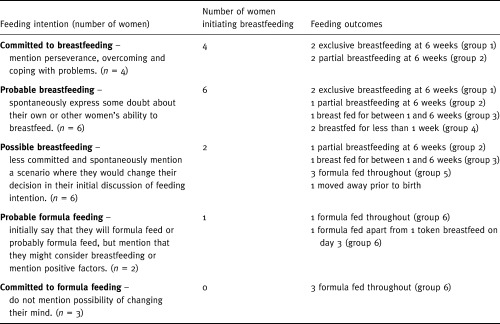

Women were classified into five feeding intention groups according to their discourse when talking about their feeding intention and six feeding outcome groups. (Table 1) Definitions of feeding outcomes are those described by Labbok and Krasovec. 18 Exclusive breastfeeding applies to babies who are given no other solids or liquids other than breast milk. Partial breastfeeding applies to babies fed by both breast and formula milk. Token breastfeeding is an occasional breastfeed. Breastfeeding initiation is defined as any baby who is put to the breast, even if only once. 1 More detail about this classification and the socio‐demographic characteristics of the sample are discussed elsewhere. 9

Table 1.

Classification of women into 5 feeding intention groups and 6 feeding outcome groups

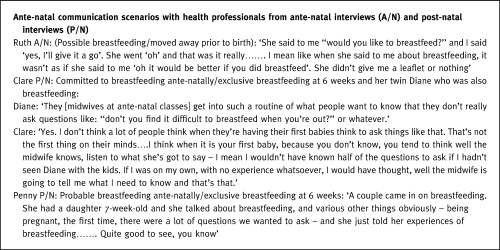

Most of the data about ante‐natal communication with health professionals was obtained at the post‐natal interview, as 15 women participated in their first interview prior to any ante‐natal care (Box 2 1). Women reported that infant feeding was seldom discussed in detail with health professionals ante‐natally. Health professionals often asked the question ‘How are you planning to feed your baby?’ which tended to produce a one word answer ‘breast’ or ‘bottle’. Any discussion focused on the health benefits of breastfeeding. Women expected health professionals to tell them what they needed to know. The more personal and practical aspects of breastfeeding, particularly breastfeeding in front of others, breastfeeding on demand and coping with new bodily experiences, like breast pain and leaking milk, were important to women post‐natally but seldom discussed ante‐natally. They were issues which some women had heard about ante‐natally through family, friends or books. Women who had seldom seen breastfeeding found these issues embarrassing and seldom raised them with health professionals. Only the more confident women with embodied knowledge gained through seeing breastfeeding regularly, discussed these more sensitive issues. Ten women attended ante‐natal classes. Looking back on these classes, women described interactive discussion with a breastfeeding mother and baby as providing more relevant preparation for breastfeeding than professionally led classes which used a more didactic ‘chalk and talk’ teaching style.

Table 2.

Box 1 Barriers to discussing infant feeding ante‐natally

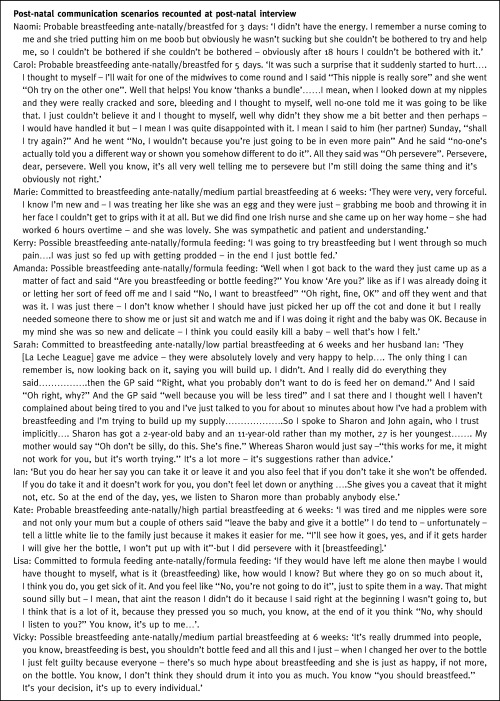

Perceived pressures (Box 3, 4 2)

Table 3.

Box 2 Communication by health professionals in the post‐natal period

Table 4.

Box 2 Contd.

Like other researchers we found that many of the women reported conflicting advice on all aspects of baby‐care, including breastfeeding. Advice about breastfeeding was received from family, friends and books as well as health professionals. Those whose family lived at a distance and those with little experience of new‐born babies or seeing someone breastfeed were more likely to complain about inappropriate communication and conflicting advice. They were also more likely to experience a mismatch between ante‐natal expectations and reality and to lose confidence in their mothering ability post‐natally. These new mothers reported difficulty keeping family, friends and health professionals happy, since everyone they met offered advice and expected their advice to be acted upon. Everyone seemed to be an expert except them. A few women described strategies where they lied to either health professionals or family to avoid conflict and maintain control of decision‐making.

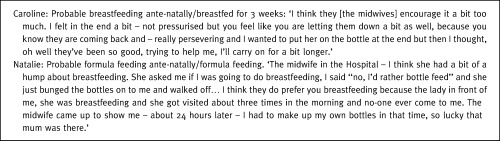

A strongly held view was that women felt pressure both to start and continue breastfeeding against their own wishes. Women who chose to formula feed reported a lack of information and often felt neglected in comparison to breastfeeding women on post‐natal wards. A more balanced approach to the provision of both verbal and written information on infant feeding was a strongly voiced recommendation made by women.

Differing goals

Some women perceived that they had differing infant feeding goals from health professionals which created difficulties in communication. The goal for health professionals seemed to be the initiation of breastfeeding then prolonging it for at least 4 months to ensure maximum health gain. In contrast, the most important goal for new mothers generally was maternal, baby and family well‐being. Women wanted a contented, thriving baby which would enable them to feel confident that they were being good mothers. This explains women’s sensitivity to and dissatisfaction with the way health professionals often talked about infant feeding. An example is the widely used statement ‘breast is best’, which was perceived as judgmental, particularly by some women who had difficulty breastfeeding. Women commented on the way that both health professionals and other breastfeeding mothers tended to emphasise successful stories about breastfeeding and say little about problems which might occur. Greater satisfaction was reported where communication was ‘woman centred’ rather than ‘breastfeeding centred.’

Words are not enough

How health professionals communicated information about infant feeding was of crucial importance to women when they were feeling physically and emotionally fragile after birth. Words alone offering support for breastfeeding were often inadequate. Women distinguished between health professionals who seemed to really care and those who appeared more impersonal. They valued midwives spending time patiently watching them feed, bath, and comfort their baby in contrast to midwives who took over the care. Encouragement, confidence building and reassurance of the baby’s enjoyment and well‐being were particularly important. Women with low exposure to new‐born babies and little family support expressed a need for an expert available to provide reassurance 24 h a day in the early days after birth.

Many health professionals told women to persevere and breastfeeding would succeed. A woman’s determination to persevere was associated with close exposure to successful breastfeeding, which provided a visual role‐model and opportunities for apprenticeship style learning. If advice to persevere was offered in lieu of practical and emotional support, it was often resented. When breastfeeding was problematic, women were often told that faulty positioning was the problem and this was often perceived by women to mean that it was their fault, leading to feelings of guilt and loss of confidence. The emotional aspects of failing to perform a bodily skill which some women had assumed would be natural and easy, 10 were strongly expressed by women but were seldom discussed with health professionals.

The majority of women waited for health professionals to be proactive and offer support with both breast and bottle feeding. This passivity reflected an underlying lack of confidence in coping with new bodily experiences following birth in an unfamiliar environment. Discourse analysis revealed contrasts in the relationships between women and health professionals. Women who spontaneously referred to ‘my’ midwife or called her by her first name were more likely to be positive about the support they received compared to women who had less continuity of care and referred to ‘a midwife’ or ‘the midwife.’ Spending time with a midwife with whom the woman had developed a personal, continuing relationship was highly valued. Often it was the return of the midwife who had attended the birth which made the difference to women who were struggling with breastfeeding. Women seemed more able to access the support they required if a personal relationship had developed.

Some women found the way health professionals touched their bodies distressing. Coming to terms with their birth experience and bodily embarrassment seemed to overshadow any interest in trying breastfeeding, which was seen as yet another invasion of their bodily privacy. Women found it more acceptable to be shown how to put a baby onto the breast than to have a midwife handling their breast to attach the baby. For many women childbirth was their first major life event and experience of being in hospital. Some described the health professionals they encountered as insensitive to their feelings about bodily exposure and contact. Coping with emotions, overcoming embarrassment and gaining body confidence were key determinants to successful breastfeeding. Many women preferred to learn how to breastfeed in a room with guaranteed privacy.

Show, inform, suggest but don’t advise

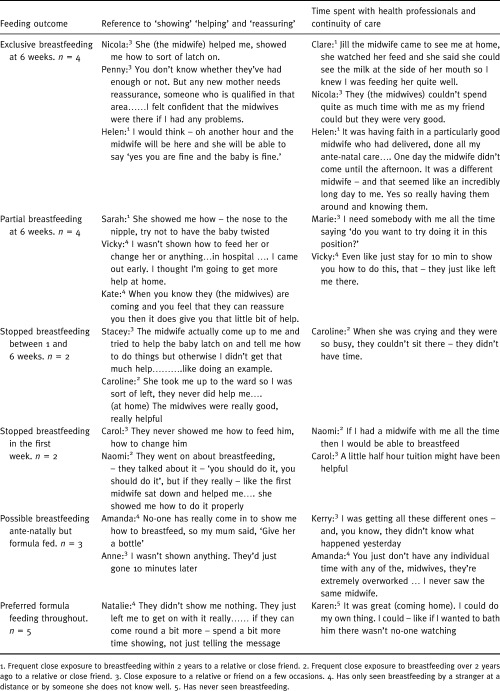

Discourse analysis revealed important differences in verbs, pronouns and nouns used by women when recounting communication scenarios with health professionals. Discourse reflecting differences in ownership of beliefs and opinions have been discussed elsewhere. 9 Apprenticeship style learning of new parenting skills like feeding, bathing and comforting a baby were important. This was reflected by women spontaneously using the word ‘show’. (Table 2) women who were ‘shown’ how to feed and care for their baby were more satisfied with their professional care than women who complained that they were not shown. The satisfied women were more likely to have seen new‐born babies and friends or relatives breastfeeding recently. This provided women with a breastfeeding role model. These breastfeeding role models were often providing the new mother with more post‐natal help than health professionals. Women seldom spontaneously used the word ‘support’ to describe communication with health professionals and the few women who did were all committed to breastfeeding and used it in the context of continuing to breastfeed. Instead the words ‘help’ and ‘reassure’ were frequently used and were important to all women.

Table 2.

Words used by women to describe communication with health professionals post‐natally tabulated according to feeding outcome with reference to ante‐natal level of exposure to breastfeeding

Women described communication scenarios where they were provided with theoretical information about parenting. The word ‘advice’ was seldom spontaneously raised by women and was sometimes used in a negative context to describe professionally centred communication. ‘Informing’ and ‘saying’ were more neutral verbs and the meaning varied more with the context. Woman centred verbs like ‘suggesting’ which facilitated women’s own decision‐making, were preferred. If advice was presented as a foolproof recipe for success and then despite perseverance it didn’t work, women experienced a sense of failure which was isolating. Some women had their expectations that breastfeeding would be easy 10 and that professionals would hold the recipe for success shattered. Suggestions that were safety‐netted with the caution that they may not work for everyone were less demoralising if they failed. Interpretation of the data suggests that facilitating women to make their own decisions was empowering and built up their confidence as new mothers during the difficult early weeks.

Conclusion

Many women in this study expressed dissatisfaction about how health professionals communicated about infant feeding. This is consistent with other reports. 3 , 4, –5 Exceptions were breastfeeding women with embodied knowledge gained from seeing breastfeeding and those with high levels of help from a relative or friend with breastfeeding expertise. This study suggests that a key to understanding dissatisfaction with communication is to acknowledge that women and health professionals may often have differing infant feeding goals. Women perceive that the health promotion goal is breastfeeding for at least 4 months which maximises health gain. 19 , 20 Maternal and baby well‐being is the priority for women generally. Health often is just a small component of this goal, which includes social relationships, body confidence, baby behaviour and emotions. The long‐term health benefits of breastfeeding are often of secondary importance for all but the most committed women.

Complaints about insufficient help and conflicting advice about breastfeeding are so important to women because many have low levels of exposure to breastfeeding and new‐born babies. They are, therefore, dependent on theoretical knowledge to learn a new practical skill. The professional response to reports of conflicting advice about breastfeeding has been to tighten breastfeeding guidelines for health professionals, in line with evidence based medicine. The assumption behind this is that professional interventions are the key determinant of breastfeeding behaviour. 21 , 22 Although consistent evidence‐based information is desirable, this may only provide part of the solution, particularly as women often turn to family and friends first. 1 As with other aspects of maternity care, 23 women want to make informed choices about infant feeding rather than feel pressurised by health professionals. The important words for women in this study were ‘help’ and ‘show’ rather than the words ‘support’ and ‘advise’ which are commonly used by health professionals. Communication is often perceived as ‘breast‐feeding centred’ rather than ‘woman centred’ at present. Attention to the process of care with more emphasis on apprenticeship style learning, together with verbal and non‐verbal communication skills training may be as important as the factual content of the message.

Contributors:

PH is the principal researcher. She was involved in formulating the study goals, data gathering, analysis and writing the paper. RP was involved in formulating the study goals, supervision of the data collection, analysis and writing the paper. Diana Thomas transcribed the interviews apart from the focus groups which were transcribed by PH. PH was working as a general practitioner at St. Stephen’s Health Centre, Bow, London E3, UK, when this study took place.

Names used in the text are fictitious to protect confidentiality.

Acknowledgements

We thank the women of Tower Hamlets and Hackney who participated in this study and the GPs and midwives who recruited them.

PH received funding from a Royal College of General Practitioners/Medical Insurance Agency Research Training Fellowship and from Grampian Healthcare NHS Trust and Grampian Primary Care NHS Trust.

References

- 1. Foster K, Lader D, Cheesbrough S. Infant Feeding 1995 London: Office for National Statistics, 1997.

- 2. Martin J & Monk J. Infant Feeding 1980 London: OPCS, 1982.

- 3. Green JM, Coupland VA, Kitzinger JV. Chapter 9: Feeding the baby. Great Expectations: a Prospective Study of Women’s Expectations and Experiences of Childbirth Hale, Cheshire: Books for Midwives Press, 1999: 365–373.

- 4. Ball JA. Reactions to Motherhood: the Role of Post‐Natal Care Cheshire: Books for Midwives Press, 1995.

- 5. Brown S, Lumley J, Small R, Astbury J. Missing Voices: the Experience of Motherhood Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994: 1–303.

- 6. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit . First Class Delivery: Improving Maternity Services in England and Wales London: The Audit Commission, 1997.

- 7. Sikorski J & Renfrew MJ. Does Extra Support for Breastfeeding Mothers Increase Breastfeeding Duration? Oxford: The Cochrane Library. Cochrane Collaboration; Update Software, 1999.

- 8. Hodnett E. Support from Caregivers During Childbirth Oxford: The Cochrane Library. Cochrane Collaboration; Update Software, 1998.

- 9. Hoddinott P & Pill R. Qualitative study of decisions about infant feeding among women in east end of London. British Medical Journal, 1999; 318 : 30 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoddinott P & Pill R. Nobody actually tells you. A qualitative study of infant feeding experiences of first time mothers. British Journal of Midwifery, 1999; 7 : 558 565. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods London: Sage, 1990.

- 12. Hoddinott P & Pill R. Qualitative research interviewing by general practitioners. A personal view of the opportunities and pitfalls. Family Practice, 1997; 14 : 307 312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miles MB & Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis London: Sage, 1994.

- 14. Strauss A & Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research. Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques London: Sage, 1990.

- 15. Ritchie J & Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG (eds.) Analyzing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge, 1994: 173–194.

- 16. Potter J & Wetherell M. Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour London. Sage Publications Ltd, 1996.

- 17. Hoddinott P. Why don’t some women want to breastfeed and how might we change their attitudes? MPhil Thesis, Cardiff: University of Wales College of Medicine, 1998.

- 18. Labbok M & Krasovec K. Toward consistency in breastfeeding definitions. Studies in Family Planning, 1990; 21 : 226 230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Howie PW, Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, Clark A, Florey CD. Protective effect of breast feeding against infection. British Medical Journal, 1990; 300 : 11 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wilson AC, Forsyth JS, Greene AS, Irvine L, Hau C, Howie PW. Relation of infant diet to childhood health: seven year follow up cohort of children in Dundee infant feeding study. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316 : 21 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Breastfeeding Working Group . Breastfeeding: Good Practice Guidance to the NHS London: HMSO, 1995.

- 22. McDowall J. Ten point quality plan for midwives in relation to breast feeding. Midwives Chronicle, 1991; 104 : 361 363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Department of Health . Changing Childbirth: Report of the Expert Maternity Group London: HMSO, 1993.