Abstract

Facilitating patient choice is an important element in respecting the autonomy of patients. Evidence‐based medicine has the potential to contribute to this process by the provision of high quality research‐based information, for use by patients and clinicians. In this paper, I analyse the processes of evidence‐based medicine in order to identify the ways in which patient choice is affected by decisions made in the development and use of evidence‐based guidelines. I argue that despite the potential contribution, the current methods and techniques of guideline production limit rather than facilitate patient choice.

Keywords: ethics, evidence‐based medicine, guidelines, patient choice

Introduction

The philosophy and techniques of evidence‐based medicine (EBM) have become increasingly important in both informing health policy and guiding clinical decisions about the care of individual patients. National evidence‐based guidelines have the potential to end postcode lotteries in health‐care, inform clinical decisions with the latest research evidence and ensure the provision of effective care. This widespread use of EBM raises interesting questions about the nature and extent of patient choice in medical care. In this paper, I argue that current techniques and practice of EBM limit rather than facilitate patient choice. This limitation of choice is not an essential feature of EBM, but rather the result of multiple factors occurring in the processes used to create evidence‐based guidelines. The first section of the paper focuses on why patient choice is important, and how patient choice works in practice. The second section briefly outlines the ways in which EBM is incorporated into practice, and then examines theoretical and practical implications for patient choice.

Why is patient choice important?

The ability to exercise choice is highly valued in many cultures as an expression of our individual identity and autonomy. Medical practice is characterized by situations in which choices are made and decisions occur, offering frequent opportunities for patients to exercise choice and for practitioners to respect those choices. Respecting patients' choices is a way of recognizing the moral status of individuals and their capacity for self‐determination. 1 Taking account of patients' desires and preferences demonstrates respect for patient autonomy, one of the fundamental principles of medical ethics. 2 , 3 Actions which do not respect the choices of others involve ethically unacceptable behaviours such as manipulation or coercion.

The kinds of choices available to patients vary along a number of parameters, such as the number of options, possible consequences, degree of expertise necessary for making a choice, or amount of information available. In cases of life‐threatening illness such as myocardial infarction or meningococcal disease the choices are stark – to accept the treatment or risk dying. Given the desire to remain alive, there is in effect no choice for the patient.

However, situations of such limited choice and serious consequences are not the norm in medicine; more frequently, there is a range of options with different possible consequences, both benefits and harms. The range of options for treatment of a painful shoulder provides a clear example. Possible treatments include at least the following: 4

• non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs;

• intra‐articular and subacromial glucocorticosteroid injection;

• oral glucocorticosteroids;

• physiotherapy (variety of techniques and modalities);

• manipulation under anaesthesia;

• hydrodilatation;

• rest, and

• complementary therapies (variety of techniques and modalities).

There may be many reasons which are relevant in the choice of one or another of these treatments, some related to the patient and some to the doctor or health service. For the patient, considerations might include cost, associated pain, dislike of tablets or injections, convenience, side‐effects, availability, duration of treatment, and interruption to other activities such as activities of daily living, work or sport. If all other factors are equal (resource implications, clinical efficacy), then it is difficult to see why the patient's choice of treatment should not be the deciding factor. After all, they are the ones most affected by their choices and the ones most likely to be aware of the personal implications and consequences of those choices upon their quality of life. 5

If we accept the importance of patient choice, the task is then to determine the best ways to facilitate patient choice in medical care. Evidence‐based medicine has a contribution to offer here, in ensuring that the information upon which doctors base their explanations, and which patients use to guide their choices, is of the highest possible standard. 6

What is EBM and how does EBM affect patient choice?

Evidence‐based medicine is `the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.' Evidence‐based medicine `integrates the best external evidence with individual clinical expertise and patients' choice' and `must be integrated with individual clinical expertise in deciding how and whether it matches the patient's clinical state, predicament and preferences.' 7

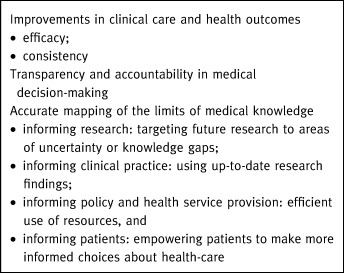

Prima facie EBM has great appeal as it aims at providing robust information about the effectiveness of medical interventions, so that patients have access to treatments that work and are not subjected to ineffective treatments. 8 Evidence‐based medicine aims to map the current extent of medical knowledge, including documentation of what is unknown, with the overall aim of improving health outcomes. The possible benefits from the provision of this information are listed in Box 1.

Table 1.

Box 1 Possible benefits of EBM

Improving patient choice is frequently cited as a benefit of EBM, leading to debate about the role of evidence in informed patient choice. 9 At the very least, patients need to understand the advantages and disadvantages of various options. 10 , 11 Models for patient choice specifically involving evidence are appearing in the literature, such as evidence‐based patient choice 12 and evidence‐informed patient choice. 13

Hope describes three components of patient choice: information, education, and power and involvement. In this model, the main goal is to enable each patient to reach an autonomous decision (irrespective of the nature of that decision), using the best available evidence as part of that decision process. The provision of evidence is considered empowering, especially in the context of patient‐centred care. In addition, Hope advocates the inclusion of patient choices in setting the questions and outcome measures for clinical research and for systematic reviews, to ensure that evidence‐based information is relevant to the concerns of patients.

Entwistle et al. define evidence‐informed patient choice as decisions characterized by the following criteria:

• the decision is about health‐care interventions or patterns of care;

• the patient is given research‐based information about the effectiveness of at least two alternative interventions, and

• the patient provides some input into the decision‐making process.

It is important to note that in both of these models, evidence contributes to the decision process but is not determining; that is, there is recognition of additional issues which are not reliant upon evidence such as the process of care. Using the example of possible treatments for painful shoulder, it will be important to have information about the effectiveness of each of those treatments, but information about the process of care may be equally important, such as need to travel for treatment, length of time off work, cost to the patient and waiting times.

This brief discussion of EBM raises questions. First, are there theoretical or conceptual problems with the idea of EBM contributing to patient choice, and second, how does EBM work in practice?

How does EBM work in theory?

As defined above, EBM involves using the best available evidence in medical decisions. This begs the question: What does `best' mean in this context? One of the aims of EBM is to move away from medicine based on tradition and opinion towards medicine based upon a secure scientific and objective base. 14 In this context, the best evidence is defined as that derived from randomized controlled trials, with the results from multiple trials combined in order to increase the strength of the evidence. Techniques of meta‐analysis and systematic review are used in this process, following well‐established protocols. The aim is to provide accurate, objective evidence about aspects of medical care, which may then be offered to patients and doctors to inform their choices. 7

However, many decisions occur during this process, and each of these decisions leads to a narrowing of focus or a judgement which affects the final results. Judgements occur in formulating the question, in deciding upon interventions to be compared, and about the nature and importance of outcomes to be measured.

These judgements occur in the original research, such as the outcomes to be measured as evidence for the effectiveness of the intervention under study. For example, in coronary heart disease primary prevention trials, outcomes include coronary heart disease related or sudden deaths, non‐fatal myocardial infarctions and unstable angina, as well as cholesterol levels. 15 The more objective or absolute the outcome (such as death), the easier it is to measure its occurrence. The assumption is that these outcomes are of relevance to those both providing and using medical care. This assumption is correct up to a point, but there can be important caveats. Patients are often interested in additional outcomes which are not always reported, such as the nature and incidence of side‐effects which may be considered minor by researchers. When the risk of a major adverse event is very low, the relative importance of minor side‐effects increases, especially when alternative treatments offer similar benefits.

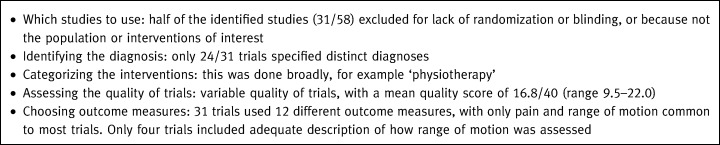

A further use of judgement occurs during systematic review, when results from multiple trials are pooled. Here decisions must be made about the scope and nature of the review, which outcomes to use, which studies to include, and what the results actually mean. An example from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of interventions for painful shoulder may illustrate some of these decisions and demonstrate how evidence about effectiveness relies upon a succession of decisions in the review process (listed in Box 2). Some of these decisions are dictated by methodological requirements, but some are based upon the assumptions, interests and values of researchers.

Table 2.

Box 2 Decisions made in the course of a systematic review of interventions for painful shoulder

The cumulative effect of these decisions is that much of the research data is excluded from consideration. Outcomes are difficult to compare because of lack of diagnostic certainty, making comparisons of efficacy impossible. Different interventions are pooled under umbrella terms so that information about the efficacy of different modes of, for example, physiotherapy are not documented. Pooling results is not possible because of the diversity in study population, outcome measures, timing of assessments or insufficient reported data. Not surprisingly, the major conclusion from this systematic review was that there is little evidence to support the use of any of the common interventions in managing shoulder pain, and that further clinical trials are needed.4

This example demonstrates the tensions generated by requirements for rigorous methodology in systematic reviews: rigorous methods lead to valid conclusions but are most workable with very circumscribed questions. The more general the topic, the harder it is to pool data from multiple sources about multiple interventions. A systematic review comparing fewer interventions (e.g. non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory vs. placebo) may have led to a more determinate conclusion. But as questions become more circumscribed, we lose utility for informing for patient choices: knowing that anti‐inflammatory substances are better than placebo is useful information, but not as useful as comparisons between the whole range of possible interventions. There are two issues here: the first is that the most accurate and valid evidence will relate to narrowly circumscribed questions, which may be of limited use for patient choice. The second is that within methodological requirements, there is scope for patient perspectives to inform choices about the populations, interventions and outcomes of interest in systematic reviews. Ignoring patient perspectives on these issues further limits the potential for EBM to contribute to informed patient choice.

Finally, when the evidence is assembled, a further judgement is required as to whether the results demonstrate effectiveness. 16 If a treatment is successful 30% of the time, we cannot assess whether or not this is effective treatment unless we know the success rates of the alternatives, and the consequences of not taking the treatment. For life‐threatening illnesses, 30% is better than zero, but if there is a 90% chance of severe side‐effects, and a 20% chance of spontaneous resolution, we may not think it so effective.

In summary, the theoretical framework of EBM aims to produce the best possible evidence upon which to base decisions, but we need to recognize that the production of evidence is a complex process involving methodologically imposed limitations and value‐laden decisions. Every decision made in the process affects the final results and the range of options about which we have evidence. The people making these decisions are clinicians, researchers, biostatisticians and epidemiologists rather than patients, so that the results of systematic reviews may not necessarily reflect the outcomes of interest to patients. Judgements about efficacy are relative, depending very much upon the context, making it crucial to include the views of those most affected.

How does EBM work in practice?

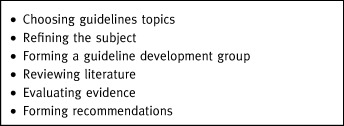

Evidence‐based clinical guidelines are currently the most common way of introducing EBM into practice, forming a bridge between research, EBM and clinical practice. Evidence‐based guidelines can be used to inform clinical decisions about individual patients. 17 The production of evidence‐based guidelines involves a number of formal stages (listed in Box 3) which have been publicized by organizations such as the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). 18 , 19

Table 3.

Box 3 Guideline production process

At what stages in this process can patient choice occur or influence the subject and nature of evidence‐based guidelines?

Choosing a topic

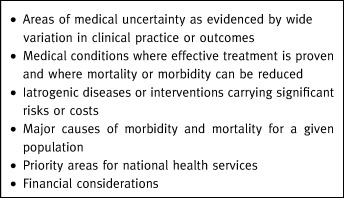

Choosing a topic is a crucial stage of the process, as this determines where efforts will be directed to assemble and review evidence. Several criteria (listed in Box 4) have been suggested. 17 , 19 , 20

Table 4.

Box 4 Criteria for choosing a guideline topic

Information from the NICE website indicates that the Secretary of State for Health and the National Assembly for Wales select topics for NICE guidelines. The proposals in the initial list were based on a careful scrutiny of topics likely to have significant impact on the NHS. 21

In addition to these criteria for prioritizing amongst possible guideline topics, there must be a reasonable belief that there is a sufficient evidence base to underpin any recommendations. This is a significant caveat, making the commissioning of guidelines dependent upon the prior completion of research in particular areas. This process is backward looking in the sense that guidelines rely upon the products of the previous 10 years' research programmes, so that areas in which there is much research activity, such as pharmaceutical interventions for cardiovascular disease, will be well represented. Other areas with less research will not be suitable candidates for guideline development. Patients do not play a major role in commissioning or directing research programmes, creating the possibility that suitable topics for which there is evidence do not reflect patients' interests.

The guideline commissioning process for both NICE and SIGN is open to nominations by interested people or groups. Theoretically, this opens the way for nominations by patients as well as health professionals; however, given the amount of work and expertise involved in nominating a topic and identifying the existence of an evidence base, nominations are beyond the reach of many individual patients. This means that the nomination process for guideline development reflects professional enthusiasms and existing research rather than patient identified concerns.

Refining the subject

The aim of refining the subject is to develop a suitable question amenable to forming the basis of a guideline. There is a tension between having an answerable question, and producing guidelines which are practical and relevant. During the process of refining the subject, the range of treatment options becomes narrowed and pre‐determined, in order to produce a manageable and answerable question. Guidelines recommend interventions for which there is evidence of effectiveness, and given the nature and hierarchy of evidence used in these assessments, pharmaceutical interventions are those for which there is the greatest evidence. This means that non‐pharmaceutical interventions such as counselling, physical therapies and lifestyle interventions, which may be of interest to patients, may be excluded from consideration because no evidence exists either for or against their effectiveness. 22 The process of refining the subject involves those patient representatives present on the guidelines boards of organizations. However, their power to shape the question may be limited by the imperative to produce a question which is answerable with existing evidence, and by other interests in the group.

Forming a guideline development group

The composition of the group strongly influences the outcome of the whole process in a number of ways. Speciality groups may rate interventions in which they have an interest as more appropriate compared with generalists. 20 Use of a multidisciplinary group may overcome some of these barriers, as does attention to group processes. However, the effective power of some group members may outweigh that of other members, leading to bias even within multidisciplinary groups. Patient representation on guideline development groups is now an accepted part of practice; however, there is little information about the functioning of guideline development groups. 23 One study on patient involvement in SIGN guideline development groups identified a number of barriers including isolation, lack of knowledge about methodological issues, lack of clarity about their role, and lack of research into aspects of care and treatment regarded as being important to patients. 24

Reviewing literature and evaluating evidence

These processes have been discussed at some length in the section on theoretical issues. However, it is worth emphasizing that decisions about which outcomes are to be counted as benefits and burdens in reviewing existing research is a crucial part of the process, and one which traditionally has relied upon biomedical markers rather than consequences which are of importance to patients. In addition, deciding whether or not a piece of information about efficacy is good evidence for an intervention requires the perspectives of those receiving the intervention. There is increasing recognition of various forms of bias which occur in systematic reviews. 25 Evidence of effectiveness may be exaggerated by publication bias and the tendency of small studies to show larger treatment effects, whilst there is less information about relatively infrequent harms.

Forming recommendations

Typically a guideline contains a list of recommendations (which may be graded according to the strength of evidence upon which they are based), such as circumstances in which a patient should be prescribed a particular drug or offered an intervention. Recommendations may be of various types depending upon the nature of the desired change in practice: 26

• initiating new management;

• preventing introduction of new management;

• increasing established management;

• reducing established management;

• modifying established management, and

• ceasing established management.

In practice, guideline recommendations are a list of commands or instructions using strongly prescriptive language. Those published by SIGN and NICE do not present recommendations as a series of options, nor do they indicate points at which patient choice may be exerted. The format of guidelines does not encourage practitioners to reflect upon the implications of the evidence, creating the possibility for confusion to occur. For example, a conclusion that there is no evidence that a specific intervention is effective may be mistakenly interpreted to mean that the intervention is ineffective.

Using the guideline

Discussions as to how practitioners should use guidelines in patient care shy away from stating that guidelines should be followed, instead suggesting three possible uses:

• as an information source for continuing professional education;

• as instruments for self‐assessment or peer review (quality improvement), and

• to answer specific clinical questions. 17 , 27

In addition, SIGN guidelines contain disclaimers to the effect that the guidelines are not standards of care and that ultimate judgement must be made by the doctor in the light of all the relevant information, sentiments echoed by NICE. 15

However, successful implementation is described as adherence to guidelines using guideline‐derived performance measures. All of the resources directed towards implementing guidelines focus upon techniques and interventions to ensure that practitioners follow the guidelines. It is possible that practitioners may use guidelines simply as a source of information and pass this on to the patient in an unbiased way; however, this is a time‐consuming process. 28 Perhaps it is more likely that time pressures and audit requirements may bias presentation of information and choices in favour of the guideline recommendations. Therefore, a doctor using a guideline in the way intended by implementation strategies will be giving directions rather than offering choices.

The evidence which had the potential to enhance patient choice has been synthesized into a list of instructions, leaving the patient with the options of either accepting or refusing the guideline recommendations. Despite the potential for EBM to improve the standard of information for patients to use in their health‐care choices, the current practice of implementing EBM through the use of guidelines limits rather than facilitates patient choice.

Conclusion

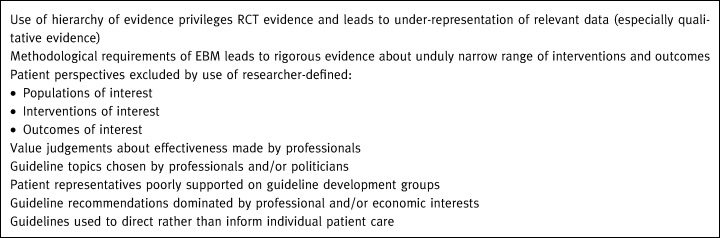

In this paper, I have argued that the current techniques and practical application of EBM effectively limit patient choices (Box 5).

Table 5.

Box 5 Ways in which the use of EBM currently limits patient choice

This limitation of choice narrows opportunities for respecting patient autonomy; having only one option to choose from appears more like coercion than informed autonomous choice. The provision of truly autonomous choices in health‐care requires the involvement of patients in the entire process of evidence production, from commissioning appropriate research to developing guideline recommendations. If health‐care is about improving health in ways which people value, this process needs to be informed by the views of those affected. However, we must recognize that patient autonomy is not the only important value in health‐care. 3 Unfettered patient choice may lead to greater inequities in health‐care through the diversion of scarce resources towards those who voice the loudest preferences, rather than those with the greatest health‐care needs. Striking the right balance between evidence‐informed patient choice and equitable use of health‐care resources requires political as well as practical solutions.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented to the Scottish Medical Groups in Dundee. I would like to thank the participants at that meeting, and also Vikki Entwistle for helpful comments. This work was supported by a fellowship awarded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (ID 007129).

References

- 1. Parker M. The ethics of evidence‐based patient choice. Health Expectations, 2001; 4 : 87 – 91.DOI: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2001.00137.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics . New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- 3. Ashcroft R, Hope T, Parker M. Ethical issues and evidence‐based patient choice. In: Edwards A, Elwyn G (eds) Evidence‐based Patient Choice: Inevitable or Impossible? Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001: 53–65.

- 4. Green S, Buchbinder R, Glazier R, Forbes A. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of interventions for painful shoulder: selection criteria, outcome assessment, and efficacy. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316 : 354 – 360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coulter A. Partnerships with patients: the pros and cons of shared clinical decision‐making. Journal of Health Services Research Policy, 1997; 2 : 112 – 121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Gilbert D. Sharing decisions with patients: is the information good enough? British Medical Journal, 1999; 318 : 318 – 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sackett DL. The Doctor's (Ethical and Economic) Dilemma: OHE Annual Lecture 1996 London: The Office of Health Economics, 1996.

- 8. Woolf S, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. British Medical Journal, 1999; 318 : 527 – 530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edwards A, Elwyn G (eds) Evidence‐based Patient Choice . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- 10. Entwistle VA, Sowden A, Watt IS. Evaluating interventions to promote patient involvement in decision‐making: by what criteria should effectiveness be judged? Journal of Health Services Research Policy, 1998; 3 : 100 – 107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Entwistle VA, O'Donnell M. Evidence‐based health care: what roles for patients? In: Edwards A, Elwyn G (eds) Evidence‐based Patient Choice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- 12. Hope T. Evidence‐based Patient Choice London: King's Fund, 1996.

- 13. Entwistle VA, Sheldon TA, Sowden A, Watt IS. Evidence‐informed patient choice. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 1998; 14 : 212 – 225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Evidence‐based Medicine Working Group . Evidence‐based medicine: a new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA, 1992; 268 : 2420 – 2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network . Lipids and the Primary Prevention of Heart Disease: a National Clinical Guideline. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 1999.

- 16. Frith L. Evidence‐based medicine and general practice. In: Dowrick C, Frith L (eds) General Practice and Ethics: Uncertainty and Responsibility. London: Routledge, 1999: 29–44.

- 17. Feder G, Eccles M, Grol R, Griffiths C, Grimshaw J. Using clinical guidelines. British Medical Journal, 1999; 318 : 728 – 730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Institute for Clinical Excellence . Clinical Guidelines Development Process Accessed on the NICE website on 31‐5‐2001: http://www.nice.org.uk/nice‐web/article.asp?a6834

- 19. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network . SIGN Guidelines. An Introduction to SIGN Methodology for the Development of Evidence‐based Clinical Guidelines. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 1999.

- 20. Shekelle P, Woolf S, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Developing guidelines. British Medical Journal, 1999; 318 : 593 – 596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Institute for Clinical Excellence . Frequently Asked Questions About Clinical Guidelines Accessed on the NICE website on 31‐5‐2001: http://www.nice.org.uk/nice‐web/Article.asp?a947

- 22. Hope T. Evidence‐based medicine and ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics, 1995; 21 : 259 – 260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wersch van C, Eccles M. Involvement of consumers in the development of evidence based clinical guidelines: practical experiences from the North of England evidence based guideline development programme. Quality in Health Care, 2001; 10 : 10 – 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carver A, Entwistle VA. Patient Involvement in SIGN Guideline Development Groups, 1999. (unpublished report)

- 25. Sterne J, Egger M, Davey Smith G. Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta‐analysis. British Medical Journal, 2001; 323 : 101 – 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Makela M, Thorsen T. A framework for guidelines implementation studies. In: Thorsen T, Makela M (eds) Changing Professional Practice. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for Health Services Research and Development, 1999: 23–53.

- 27. Grimshaw J, Eccles M. Clinical practice guidelines. In: Silagy S, Haines A (eds) Evidence‐based Practice in Primary Care. London: BMJ Books, 1998: 110–122.

- 28. Schofield T. Evidence‐based patient choice in primary health care. In: Edwards A, Elwyn G (eds) Evidence‐based Patient Choice: Inevitable or Impossible? Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001: 181–190.