Abstract

Objective To compare the extent to which women in three European countries were able to exert influence over the organization and delivery of maternity policy and the factors likely to determine their success.

Design Semi‐structured interviews used to collect data, which was analysed in a framework that emphasized the importance of contextual environment.

Setting and participants Representatives of 19 lay maternity user organizations in England, the Netherlands and Germany interviewed during 1996 and 1997.

Variables studied Each interviewee was asked to provide details of their aims and objectives, activities and networks and perception of success. Four areas of contextual environment were used to account for variations.

Main outcome measure Self‐reported accounts of success in influencing policy agenda, credibility with opinion formers, campaigning activities and political networking were compared between and across countries.

Results Marked differences between both the aspirations and the achievements of groups in the three countries.

Conclusions Understanding the differences between countries in relation to user involvement entails locating research within the social, political and cultural context of health‐care, consumerism and citizen participation.

Keywords: campaigning, comparative research, Europe, maternity care, policy influencing, user organizations

Introduction

In attempting international comparisons in the field of health policy, Kirkham‐Liff describes the objective as: `find out what works, why and under what circumstances, and then aggressively develop means to translate these comparative findings into new models for organising and delivering health‐care'. 1 For those looking to build on successful user involvement initiatives this is a seductive proposition, as the evidence base for user involvement is relatively new and as yet not particularly well developed. 2 , 3, –4 However, there are many useful warnings for those attempting comparative health research. 5 , 6, –7 Not the least is the need to balance the desire to seek universal explanations across different contexts, with the increasing complexity of political and social life, which makes for increased divergence between and within countries.

This paper reports research that assessed the campaigning activities of user groups in three European countries to compare the extent to which women in those countries were able to exert influence over the organization and delivery of maternity policy. As well as reporting the similarities, differences, strengths and weaknesses of approach in each country, the paper also seeks to explore just how much we can usefully learn from comparative research. The objective was to test theories about policy making. For example, are similarities in economic growth and the advancement of medical technology enough to explain common approaches to policy in the countries being studied? Conversely are differences in national culture and political ideology sufficient explanations of policy variation? Comparing the power structures and stakeholder groups within three countries is used here to try and explain why countries adopt different responses to broadly similar issues.

The setting of maternity care was chosen because the early 1990s had seen consumer pressure incorporated into English health policy, firstly in a House of Commons Select Committee Report that recommended a shift towards `woman‐centred care' and secondly through a Government policy initiative `Changing Childbirth' which sought to implement woman centred care principles. 8 Lay maternity user groups had played a central role in campaigning for these initiatives, supplying evidence and advising on implementation. At the same time, Dutch maternity care, which has traditionally been viewed by natural childbirth campaigners as a `gold standard', was beginning very tentatively to move in the other direction with creeping medical control and a declining home birth rate. 9 This research sought to explore how and why Dutch maternity organizations were responding to this challenge. Finally, in Germany the provision of maternity care was broadly similar to that which existed in the UK prior to the reforms of the 1990s highly medicalized, highly interventionist, fragmented and unappreciated by its users. Could German user groups learn anything useful from the experience of the English groups?

Method

Using three different countries, the principle aim of this research was to critically assess the influence that users of maternity services believed they were able to exert on policy making. This involved collecting and analysing data from the three countries and comparing findings to identify strengths and weaknesses within the organized consumer movement around maternity care, to draw conclusions about the extent to which there were similarities and differences amongst the groups and to draw conclusions about the ability of each to influence policy.

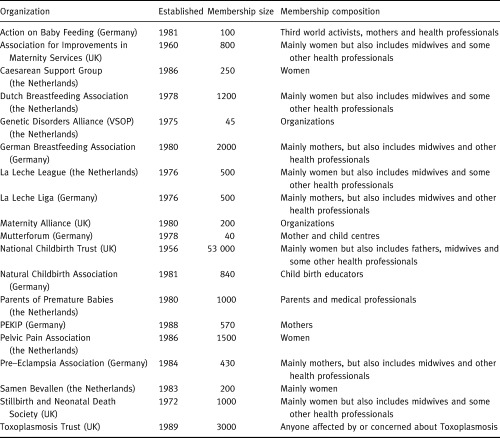

The data source for the comparisons reported in this paper is interviews with a sample of user group representatives in the Netherlands, England and Germany identified through a range of personal contacts and professional networks. In some cases the paid official of an organization was interviewed, where none existed, volunteers were interviewed in their own homes. In all 19 of 35 organizations identified agreed to be interviewed (see Table 1). The sample size was constrained by the time available, the logistics of travelling to meet people and whether representatives of the groups could speak English. The intention of the research was to allow women to tell their own stories and the interviews were deliberately not triangulated with data from official sources and health professionals. For each a semi‐structured interview schedule was used to guide discussions, which were recorded and later transcribed in full. Each interview lasted approximately 1.5 h and covered the groups origins and values, their organizational structure, funding and governance, their activities including networks and external relations, their relationships with other stakeholders and credibility with policy makers and finally their assessment of their success in influencing maternity policy. The interviews took place during 1996 and 1997.

Table 1.

Maternity user organizations surveyed in this comparative research

Results

Characteristics

The membership of most of the groups comprised women who had used maternity services, together with a smaller number of interested or committed health professionals. In England and the Netherlands the groups had originated from individual experiences, most commonly negative, of using established services. The motivation to improve services for others led these women to join the groups and remain active. In Germany, the groups were more likely to have been founded either by or with professionals and the genuine grass‐roots lay organization was the exception rather than the rule.

In Germany and the Netherlands the groups tended to be small – an average of under 1000 members and formed roughly within the same time frame, from the mid 1970s to the mid 1980s, coinciding with the development of a more general women's movement and women's activism. 10 , 11 In England no common picture emerged. The largest group, the National Childbirth Trust (NCT) was exceptional both in its size and longevity. Established in 1952 and with 53 000 members NCT is unlike any other maternity user group in Europe. Its presence has undoubtedly affected other English groups, which occupy specialist niche positions representing women with very particular problems.

Agenda

For the majority of groups in this study, pregnancy and childbirth are viewed as natural physiological life events that should be as free as possible from medical intervention. Almost all of the groups shared a belief in the naturalness of women's ability to carry and deliver a child, and saw the routine application of medical technology as disempowering; preferring the input of midwifery rather than obstetric care during pregnancy and childbirth. Equally in all three countries users tended to believe that the existing systems failed women and that health professionals failed to take women seriously.

`…the issues are the mythology of normal birth and the reality of so many women continuing to have induced, accelerated and drugged labours and not even realising that it was unnecessary…reducing the power of obstetricians…' (English representative)

For all, the key to improved services for women lay in greater and better information. Information was seen as the key to women having the opportunity to make choices about the nature of their care, to understanding the processes and options and to being empowered to take greater control of their pregnancies and childbirth experiences. Information was seen as the mechanism by which individual women could ensure for themselves a more satisfying experience.

In all three countries, groups wanted health professionals to pay greater attention to the psychosocial aspects of pregnancy and to spend more time with women. Even in the Netherlands, where childbirth is subject to the least medical control, women believed that their emotional and individual needs were neglected. For the Dutch groups the desire for more and better information, was not seen as a challenge to the existing system. In fact, these groups were generally content and supportive of the dominant approach to maternity care and childbirth, and were not seeking major structural change to services.

`…the system is fine, but what has to change is the attitudes, the care givers want to support breastfeeding but they don't know how…' (Dutch representative)

By contrast the German and English groups were challenging the dominant medical paradigm. The groups in Germany were the least satisfied with the provision and approach to care, which was the most highly medicalized and had the highest intervention rates. German women were the most frustrated by their limited choices and the lack of personal control over their care.

`…the mothers are looked at patients now and that is not right, motherhood is not an illness. She is responsible for her child and she can make her own decisions and that is not accepted by the medical profession…' (German representative)

The English groups had historically shared and articulated similar concerns. However, through‐ out the 1990s they played a key part in securing major changes to the way maternity care is delivered in the UK. 12 Having `won' a commitment to woman‐centred care from policy makers these groups were largely concerned with implementation at a local level.

Activities

Overall the activists within the majority of groups conformed to the traditional self‐help model of lay representatives whose expertise is derived from both their own, and also other members' experiences. They provided information, advice and support on an unpaid basis including: telephone help‐lines, provision of information leaflets and booklets, local meetings, classes and groups, peer counselling and support, teaching or preparing women for natural childbirth and breast‐feeding. Amongst all these groups it was the lay perspective that was most important. This was most strongly developed in the Netherlands, which has a long social tradition of `lotgenotencontact', or mutual support based on shared experiences. It was the least identifiable in Germany, where the enormous diversity between groups, particularly in their objectives, makes it difficult to describe a `childbirth movement', as such.

`…it was set up by a group of mothers who felt there was a need for support and information on a mother‐to‐mother basis. This has gradually developed into people with extra training…' (Dutch representative)

`we also have what we call “frienders” who have been trained. They have been bereaved parents for some time. They are trained through our local workshops…' (English representative)

In all three countries the services provided by the groups were outside the remit of the mainstream health services and were not covered by national funding arrangements. This meant that women wishing to make use of these services paid directly, in addition to insurance or taxation contributions. All of the groups provided members and particularly those that became active, with personal development, the opportunity to acquire new skills and friendship bonds. Even women in the smallest organizations described their personal experience of growth and development as a consequence of involvement. This included increased self‐confidence and assertiveness, as well as skills of writing, speaking, counselling and teaching gained through participating in the group's activities. All of the groups also provided a focus for developing relationships, breaking down social isolation and widening social contact. In all three countries women found membership of these groups personally empowering and within many, individual women gained the confidence and ability to enter public life. Thus whilst groups might not describe themselves as `feminist', they fulfilled a very feminist objective of increasing women's self‐confidence and encouraging and supporting their participation in civil life.

Whilst the groups were commonly self‐help, there was a great divergence in the level and rigour of preparation and training that active group members experienced. In the Netherlands arrangements were very informal and active members become `expert' by sharing information and through their own experience. In Germany, groups had devised sophisticated training programmes for activist members with minimum entry qualifications and an accredited certificate. These training programmes are highly professionalized, externally validated and developed in association with health professionals. The English groups tended to fall between these poles, with the smaller groups providing no formal training for volunteer advisors, through to programmes of in‐depth education and training for NCT teachers that are quasi‐professional in nature.

Credibility and contacts

The extent to which the groups formed credible relations with other relevant stakeholders, their external profile and their access to channels of influence also showed a high degree of divergence. Almost without exception the Dutch groups had no external public or political profile. Each organization tended to operate independently and there was very little constructive networking or collaboration between the groups. Neither had they established working relations with policy makers, politicians, professionals or the media and consequently were largely unknown and disregarded as contributors to any policy debates.

The Dutch groups operating exclusively at the local level of providing individual support and advice had been able, on an ad‐hoc basis, to form relations with individual hospitals and health professionals. This recognition of the expertise of users is a cultural norm, but remains dependent on personal relationships and local circumstances. In general, the Dutch groups were `outsiders' – beyond the scope of established power and policy structures, and perceived that they had no credibility from which to negotiate with stakeholders on behalf of their members.

`…I should like it if they (policy makers) asked us our feeling because we have a lot of ideas, but they don't work like that…' (Dutch representative)

The German groups had a slightly higher external profile than the Dutch, and were more active within the wider women's movement and within trade unions; but remained unknown by government departments and ignored by policy makers. Some had developed formal relations with professional bodies and this was reflected in the extent to which these groups had `professionalized' their own activities.

`… I would say first reaction when they hear about us is one step back, but most have no idea. They just know we want to change something, so they resist…' (German representative)

In England, all of the groups had highly developed external relations and were aware of the different channels through to national policy makers, investing heavily in securing access to these. Even the smaller groups had cultivated effective external relations and established credibility with key stakeholders. Most had also developed local contacts with individual hospitals and health professionals. By forming alliances at local level the groups attempted to influence both the delivery of services and the attitudes and behaviour of staff.

`…there seems to be a much greater feeling in the DoH that you need to take user groups seriously and that users groups have something very good to offer…' (English representative)

The likelihood of groups being viewed as credible was associated with their ability to demonstrate expertise and to offer something useful to policy makers. In England groups had worked hard to position themselves alongside professionals who shared their views, to demonstrate research‐based evidence for their demands and to cultivate media attention for their particular cause. These groups were making the transition from `outsider' to `insider' groups, with many represented in the planning of services at local level and in the discussion of national policy.

Success in influencing policy

In all three countries, groups had been most successful when they had become valued by key policy stakeholders for the expertise they were able to contribute. Thus even where groups are challenging existing orthodoxes, they are able to receive a sympathetic hearing, if they have sufficient credibility.

Amongst the Dutch groups there was neither the inclination, motivation nor ability to pursue a campaigning agenda or seek to influence direct policy making. The Dutch groups were focused wholly on supporting and empowering individuals, who then act in isolation to secure a more satisfying personal experience. The focus of the Dutch group's activities was in providing personal solutions to individual problems. None of the groups aggregated the individual experiences of women to press for common improvements, nor was there a collective sense of injustice that things could and should be better. Moreover, collective action was largely seen as inappropriate and a diversion from the primary function of supporting individuals. The exception to this was Vereniging Samenwerkende Ouder en Patiëntenorganisaties [Genetic Disorders Alliance] (VSOP), the umbrella organization for genetic disorders groups. Interestingly, this is the only Dutch group that does not provide services direct to individuals. The conclusion that might be drawn is that Dutch groups find individual support and collective campaigning mutually incompatible.

`…we get the itches when things are not how we want them to be and we would rather shout out loud, but we think empowering women is safer and more steady way to work from bottom to top…' (Dutch representative)

Amongst the German groups there was a recognition and understanding of the need to take collective action to press for positive change throughout the system. However, most of the groups found themselves frustrated, both by their own limited resources and by organizational constraints in translating aspirations into action.

`…we wanted to visit 40 hospitals but could only get into 18. One administrator told our researcher to leave because it was not policy…to allow people to come and ask questions. And if it was possible to go in, it was only possible to interview one health professional, it was not possible to visit the mothers on the maternity ward…' (German representative)

Between the groups themselves there was a high level of networking, information exchange and collaboration, which meant that the groups were able to both diagnose the problems within mainstream provision and articulate solutions. Only one group had developed expertise as a lobbying pressure group, using techniques such as commissioning reports, targeting opinion formers and co‐ordinating letter writing, etc. The other groups have been unable to locate the appropriate mechanisms or channels for collecting and presenting the collective experiences of their members. Only the network of Mother Centres had succeeded in combining support and services for individual women, with the articulation of a common agenda, based on the experiences of those women.

In England, all of the groups, regardless of their size or funding identified campaigning and influencing as being as important as their self‐help activities. There was no real tension between the individual support and campaigning roles, with one being seen as essentially supportive and enhancing the other. Generally self‐help and individual support was provided through the local networks and by volunteers, whereas the campaigning role was undertaken by paid staff within the national headquarters. These groups which identified themselves as part of a larger consumer movement in health, believed it was important to contribute a user perspective in both the planning and delivery of services. All therefore contributed to policy making through research, publications, lobbying and networking. All of these groups contributed to the major review of maternity policy initiated by the House of Commons in 1991, submitting evidence individually and working together to lobby MPs and civil servants, professionals and managers. All then produced additional evidence as the Changing Childbirth policy was formulated.

`…we did our report that went into the Select Committee, we said this is what women want, these are the issues for women and here is the evidence that backs it up…' (English representative)

Discussion

The UK, the Netherlands and Germany are three countries of broadly similar socio‐economic background and national wealth. 13 Each has well developed health services and maternal outcomes are not significantly different. In each country user groups have become established around the same agenda and demands and these groups are largely providing similar services and support for individual women. However, as campaigning organizations or influencing organizations the three countries display markedly different tactics and have had markedly different success.

A simplistic comparison of the three countries would suggest that users in the UK have been more successful in influencing policy and therefore groups in the Netherlands and Germany should seek to emulate them. However, this is the point at which comparison becomes tricky. As May asserts the primary problems of comparative analysis lies in: `the response of health services to common health challenges will always be linked to the features of the country in question … each health care system is firmly embedded in its own society'. 14 Comparing discreet areas such as user influence without reference to the overall context of a country can therefore be misleading. So what could account for the differences in approach and success amongst the groups in each country? I suggest four broad contextual features account for the differences between the three countries. First the organization and delivery of health‐care; secondly the historical traditions of maternity care; thirdly the emergence of a consumer movement in health‐care and lastly the development of women's activism.

The organization and delivery of health‐care

The most obvious difference between the English health services and those in Germany and the Netherlands is its philosophical basis. The English national health service (NHS) is a product of the Beveridge analysis of welfare and is based in a model of tax‐based funding and universal access, whereas the other two countries owe their origins to the Bismarkian model of contribution based funding and entitlement. One consequence of this is an enormous difference in the number of significant players any campaigning organization must seek to influence. In England all NHS hospital trusts have a line of accountability to the Secretary of State, through a civil service mechanism that is also both the funding route and the engine of policy. In both the Netherlands and Germany there are a multitude of quasi‐independent not for profit insurers and providers, each with only weak links to government, which anyway play a limited role in driving the organization and delivery of services, made even worse in federal Germany where responsibility is divided between national and state governments.

Within health services, user groups in these countries have very different relations with key stakeholders. In the Netherlands, groups are less openly critical of the medical profession and least likely to challenge medical authority; their tactics have been an attempt to work with medical professionals and to discreetly educate them in an alternative paradigm. In Germany the groups are split between those that have been established and work largely in conjunction with the medical profession and are not therefore seen as a challenge to medical legitimacy; and those that seem to be completely ignored by the medical profession, because their perspective is so very different. What marks the activities of English user groups over recent years is their ability to get close to the medical profession, by identifying and nurturing individual professionals sympathetic to their views, whilst at the same time remaining independently critical of practices and policies they opposed.

In terms of working with service providers, Dutch health‐care providers were open and receptive to user groups distributing their literature and advertising meetings. Groups were perceived by professionals, to be complementing and supporting rather than challenging medical orthodoxy and were therefore welcomed into institutions. The role of `self‐help' is recognized and respected within the Dutch health system. 15 By comparison, German hospitals appeared to adopt a much less relaxed attitude towards promoting the existence of user groups. The German groups did not find it easy to distribute their literature or advertise local meetings within institutions. Hospitals clearly felt it was inappropriate to promote alternatives to the dominant medical paradigm and user groups were made unwelcome and discouraged from participating in the local organization and delivery of services. Relationships with health professionals were wholly reliant on local individual contact, with no formal relationships existing between the groups and professional organizations.

The traditions of maternity care

In Germany and the Netherlands the user groups' ability to influence has been further limited by a conceptual difference between themselves and policy makers. Quite simply, the maternity services have not formed part of the agenda for politicians, policy makers or professionals and there appears to be no dialogue between those articulating the medical and natural paradigms. This is most obvious in Germany where the debate about natural childbirth as an alternative to the existing highly medicalized approach is limited to the small circles of these user groups and some midwives.

In both countries groups express the desire to influence government, but acknowledge that in most cases they are virtually unknown or disregarded. By contrast, maternity care has been the subject of political and public attention in England for many years. The arguments of the natural childbirth lobby gradually built up a head of steam until they became mainstream concerns. Once the official policy of government was to acknowledge and seek to reduce unnecessary interventions, the ability of user groups to influence was assured.

The paradox in the Netherlands is that whilst its maternity services have until recently been universally envied by natural childbirth campaigners, as a model that is woman‐centred, reflecting the normality of childbirth and where medical control has exerted least control; this very domestication of birth (with a high proportion of deliveries still occurring at home and a philosophy that places pregnancy and childbirth firmly within the social/domestic setting) also means that pregnancy care remains a private–personal issue, not a public–political one.

The emergence of a consumer movement in health‐care

Unlike other Dutch patients' groups, the groups in this study are politically unsophisticated and have not developed beyond a self‐help/mutual aid role. Whereas the wider Dutch patients' and consumer movements has enjoyed official recognition and incorporation within the policy‐making process, 16 users of maternity services have exerted no collective influence over recent policy decisions. The groups do not participate in the powerful Dutch patients association (National Patients and Consumers Federation) and do not understand the term `consumerism' as applied to their activities.

The German groups are characteristic of German patients organizations in general, struggling to influence either policy or service delivery. Consumerism as a concept in health was alien to all of these groups and during the course of this research nothing resembling a national patients association was identified. Maternity users in Germany articulate dissatisfaction with existing provision and by coming together are able to provide for themselves much of the information and psycho‐social support that is lacking. What they have been unable to do is to convince policy makers of the need to radically overhaul services to better meet women's needs and desires.

In the Netherlands, patients'/users' rights are well established, covering entitlements and access to information, etc., and at the same time the provision of maternity care is on the whole accepted and acceptable to users. 17 Where users are dissatisfied formal official channels for redress exist, as do support structures. The role of user groups is therefore seen as helping individual women negotiate their way around a flexible and responsive service, to give them the information and confidence with which to enforce their rights and to provide complementary services that enrich women's experiences. That the Dutch groups universally emphasize the importance of information (more of it, more accessible) underlines their belief that individuals can successfully influence their care if they are provided with the right tools.

In Germany health entitlements are also enshrined in the civil code and citizens are well used to enforcing their rights as a way of influencing the services they receive, although patients' rights do not formally exist. 18 Moreover the German tradition of voluntary self‐help means that gaps or failings within established services are often met by voluntary groups and there is a hazy distinction between official public provision and alternative semi‐private provision. 19 Provision is fragmented amongst a wide and diverse range of suppliers and patients have the ability to choose and to change care provider. In Germany, women who are dissatisfied with the orthodox provision of care have the ability to `opt‐out' and choose an alternative provider. The role of the user groups is to provide a woman‐centred alternative, to fill gaps in services not provided and to offer women greater choice.

In the UK, neither of these approaches has been either appropriate or relevant. The failure to include social rights within the legislative framework means that whilst the Secretary of State has a general duty to maintain a NHS, citizens have no enforceable rights to specific care or specific services. 20 Equally, the all‐embracing nature of the NHS has restricted the development of private and voluntary alternative providers; maternity care is not covered by private health insurance, and midwives find it almost impossible to work independently. At the same time patients rights have traditionally been poorly defined and difficult to enforce. Despite the introduction of Patients' Charters, users of services have few enforceable rights and are largely dependent on the range of services available from their local provider. 21 Within such a scenario, a campaigning role has been the most successful way of influencing policy and provision. The centralized nature of the UK health service means that significant changes to provision at local level need authorization from central government.

The development of women's activism

In all three countries, groups define themselves as `women's organizations' and are strongly woman centred. However, most also feel uncomfortable applying the label feminist to themselves. The English groups and the German Mother Centres are the most likely to describe their objectives in feminist terms; of challenging traditional power relations and creating a fairer society, in which women's needs are given equal weight to men's. For the Dutch groups, `feminist' was perceived as meaning separatist and confrontational with men.

The Dutch groups explicitly reject the definition of `political' to describe themselves and their activities, whereas in both Germany and England groups tend to define their objectives as political and see their own concerns within a broader social context. This reflects prevailing social values: in the Netherlands `the family' is not a political issue or part of the agenda of political organizations; whereas in both England and Germany political parties, trade unions, academics and the media are involved in on‐going debates about family structures and the best way to support and balance childbirth and childrearing with paid work. 22 , 23

Consequently issues around pregnancy care and childbirth are not politicized in the Netherlands and have not formed part of the wider agenda of women's health or consumerism. Thus trade unions, women's groups, academics, etc. have not taken up the needs of women as mothers within their campaigning agendas. Without the background of a national debate on men and women's gendered roles, such as paid employment and childrearing, there is less receptivity and awareness of gender issues in health generally. 24

Amongst the English groups the awareness of a much broader agenda has formed the backdrop against which their campaigns have gained greater legitimacy and received wider support. In England the feminist movement has been responsible for turning the personal into political. The way that women are treated as mothers is viewed as a reflection of the way they are treated in society. Thus feminists and trade unionists who may not be interested in the provision of maternity care per se, see it as a symbol of women's wider oppression and have made connections between women's powerlessness at the time of birth, and gender issues such as: division of labour in paid work and in the home; male‐defined models of health and illness; women's rights as workers and equal pay; women's exclusion from senior decision‐ making posts within the health service, etc.

In Germany political debates about the nature and role of the family in modern life are part of the mainstream agenda. However, this has been a predominantly economic debate, placing it squarely within the public (male) arena. Issues such as women's empowerment in pregnancy and childbirth are totally divorced from these debates and remain in the private (female) arena.

Conclusions

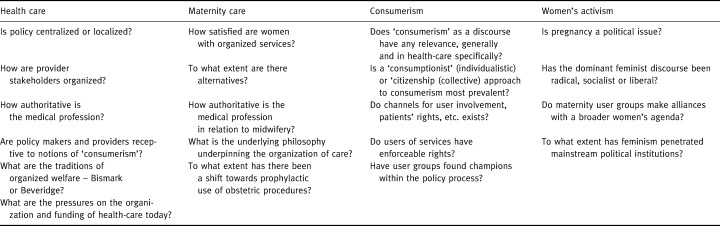

In terms of the first objective of this research, the results show that whilst users of maternity services were successful in influencing maternity policy and service delivery during the 1990s, users in the Netherlands and Germany were not influential. However, this research has demonstrated that international comparisons can throw up more questions than answers. And whilst the answer to the question `why do the Dutch groups behave the way they do?', `Because they are Dutch', may not seem very satisfactory, it does alert us to the complex constellation of contextual factors that lie behind any given health organization or policy initiatives. In this case four broad areas of context have been identified, within which very specific differences between countries' political, social and medical traditions are to be found. In terms of the second objective of this research to determine whether comparative research is useful, it suggests that Kirkham‐Liff's idea of learning and copying between countries is too simplistic. Rather the value of comparative research lies in our ability to better understand developments within single countries. This research confirms Mays' assertion that through comparative research we can begin to `understand and explain the ways in which different societies and cultures experience and act upon social, economic and political change'. The output from this research is the understanding that in order to compare user involvement in maternity care, analysis must be grounded in a constellation of contextual questions. Table 2, summarizes the contextual questions that relate to the areas of health‐care funding and organization, traditions of maternity care, significance of a consumer movement in health and place of women's activism within the health agenda. The author hopes that using and adapting this approach to identifying specific relevant contextual factors may assist international comparisons of user groups in different settings.

Table 2.

A contextual matrix affecting the ability of maternity user groups to influence policy

References

- 1. Kirkham‐Liff B. Integrating the Health Care System – Lessons Across National Borders Michigan, USA: Frontiers of Health Service Management, Vol. 11, no. 1, 1994.

- 2. Entwhistle VA, Renfrew M, Yearly S, Forrester J, Lamont L. Incorporating lay perspectives: advantages for research. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316 : 463 – 466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barnes M, Shardlow P. Effective consumers and active citizens: strategies for users influence on services and beyond. Research Policy and Planning, 1996; 14 : 33 – 38. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wood B. Patient Power? The Politics of Patients' Associations in Britain and America . Bucks: Open University Press, 2000.

- 5. Cochrane A, Clarke J. (eds) Comparing Welfare States – Britain in an International Context . London: Oxford University Press/Sage, 1993.

- 6. Immergut E. Health Politics – Interests and Institutions in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- 7. Light D. Comparative Models of Healthcare System, with Application to Germany, Unpublished paper. New Jersey, USA: Princeton University, 1993.

- 8. Department of Health . Changing Childbirth London: HMSO, 1993.

- 9. Wiegars T, Van Der Zee J, Keirse M. Transfer from home to hospital: what is its effect on the experience of childbirth? Birth, 1998; 25 : 19 – 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hermsen J, Lenning A. Sharing the Difference – Feminist Debates in Holland London: Routledge, 1991.

- 11. Kolinsky E. Women in Contemporary Germany. Oxford: Berg Pubs, 1993.

- 12. Garcia J, Redshaw M, Fitzsimons B, Keene J. First Class Delivery: A National Survey of Women's Views of Maternity Care London: Audit Commission, 1998.

- 13. Normand C, Vaughan J. Europe Without Frontiers Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 1993.

- 14. Beck E, Mays N. Health care systems in transition – confronting new problems in changing circumstances. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 1996; 18 : 254 – 257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Donker M. History of Dutch consumer groups. In: Hermans H, Casparice A, Paelink J (eds) Healthcare in Europe After 1992. London: Dartmouth, 1992.

- 16. Andeweg R, Irwin G. Dutch Government and Politics London: Macmillan, 1993.

- 17. Tugend A, Harris L. Patients rights in Europe. Eurohealth, 1997; 3 : 6 6. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seitz R, Koning H, Jelastopulu E. Managed Care – An Option For The German Health Care System. London: Office of Health Economics.

- 19. Giaimo S, Manow P. Institutions and ideas into politics: health care reform in Britain and Germany. In: Altenstter C, Bjorkman J (eds) Health Policy Reforms: National Variations and Globalization. London: Macmillan, 1997: 175–202.

- 20. Plant R. Citizenship rights and welfare. In: Coote A (ed.) The Welfare of Citizens: Developing New Social Rights. London: IPPR/Rivers Oram Press, 1992: 15–30.

- 21. Pollit C. The citizens charter: a preliminary analysis. Public Money and Management, 1994; 14 : 9 – 14. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lovenduski J. Women and European Politics: Contemporary Feminism and Public Policy. Sussex: Harvester Publishers, 1986.

- 23. Bryson V. Feminist Debates: Issues of Theory and Political Practice London: Macmillan, 1999.

- 24. Hunt K, Annandale E. Relocating gender and mortality. Social Science Medicine, 1999; 48 : 1 – 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]