Abstract

Objectives To investigate the involvement of users in clinical governance activities within Primary Care Groups (PCGs) and Trusts (PCTs). Drawing on policy and guidance published since 1997, the paper sets out a framework for how users are involved in this agenda, evaluates practice against this standard and suggests why current practice for user involvement in clinical governance is flawed and why this reflects a flaw in the policy design as much as its implementation.

Design Qualitative data comprising semi‐structured interviews, reviews of documentary evidence and relevant literature.

Setting Twelve PCGs/PCTs in England purposively selected to provide variation in size, rurality and group or trust status.

Participants Key stakeholders including Lay Board members (n=12), Chief Executives (CEs) (n= 12), Clinical Governance Leads (CG leads) (n= 14), Mental Health Leads (MH leads) (n= 9), Board Chairs (n=2) and one Executive Committee Lead.

Results Despite an acknowledgement of an organizational commitment to lay involvement, in practice very little has occurred. The role of lay Board members in setting priorities and implementing and monitoring clinical governance remains low. Beyond Board level, involvement of users, patients of GP practices and the general public is patchy and superficial. The PCGs/PCTs continue to rely heavily on Community Health Councils (CHCs) as a conduit or substitute for user involvement; although their abolition is planned, their role to be fulfilled by new organizations called Voices, which will have an expanded remit in addition to replacing CHCs.

Conclusions Clarity is required about the role of lay members in the committees and subcommittees of PCGs and PCTs. Involvement of the wider public should spring naturally from the questions under consideration, rather than be regarded as an end in itself.

Keywords: Lay board members, patients, primary care groups/trusts, users

Background

Clinical governance is a key element of the strategy of quality improvement in the UK NHS, ongoing since 1997, which is also intended to strengthen principles of openness, responsiveness and accountability. Arguments for involving lay stakeholders in this agenda include restoration of public confidence in the NHS, improved outcomes for individual patients, more appropriate use of health services and potential for greater cost‐effectiveness. 1

While accountability in clinical governance is considered to extend in an `upwards' [Primary Care Groups/Trusts (PCGs/PCTs) and Health Authorities] and `downwards' (local community and patients) direction, as well as horizontally to peers, it has been pointed out that `downwards accountability to communities of patients is likely to be the aspect of accountability which will have the least attention paid to it in the short term'. 2 Accountability in the NHS generally has been seen to take the form of formal accountability upwards matched by informal accountability downwards and has coexisted uneasily with professionalism, the central notion being that `he or she is accountable only to his or her peers'. 3

There has been little empirical research into public involvement with primary care in the UK but the evidence we have suggests a strong reliance on ad hoc and superficial methods such as patients' participation groups or feedback from individual patients. Those general practices that have involved users in planning or decision‐making appear exceptional. 4 , 5 There is little consistency or uniformity among patients' participation groups. They exhibit a wide variety of purposes 6 and there have been doubts about the degree to which group members are representative of patients as a whole and of those whose health needs are greatest. 7 In its study of fund holding, the Audit Commission found a poor record of involving the public, 8 despite the onus established in the Accountability Framework for GP fundholding 9 on being accountable to patients and the wider public.

Concepts of `involvement'

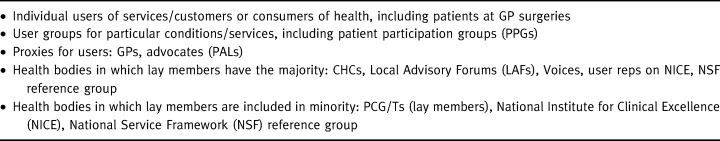

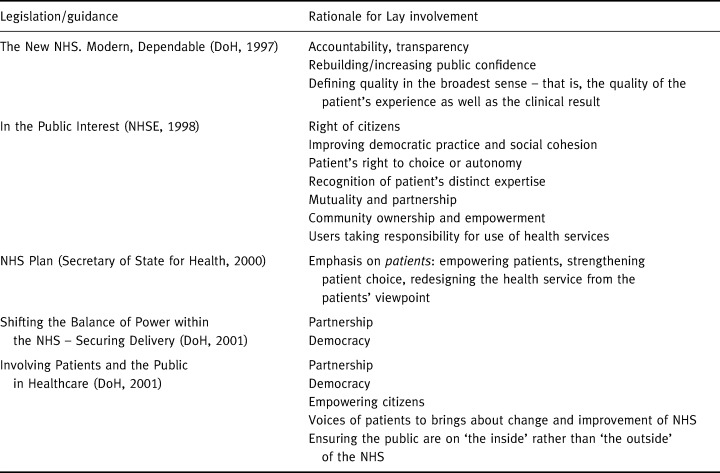

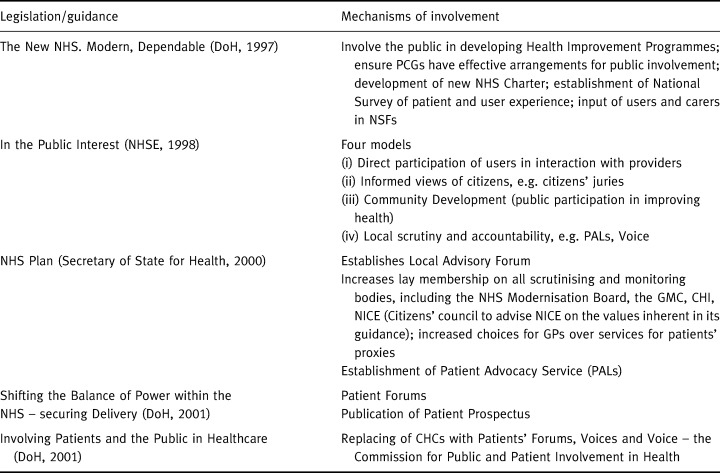

Pre‐1997 `involvement' of lay people – as individual users of services, user groups or local communities (see Table 1, below) – was often conceptualized within two contrasting frameworks: the consumerist approach, implemented through quasi‐markets since 1991; and the citizenship approach, in which the emphasis was on the rights of citizens within a democratic society. With the introduction of the `new NHS', under a Labour government, markets, contracts and charters – all keywords defining the `old' NHS of the 1980s – were replaced by a new set of key concepts, reflecting the emphasis on democratic accountability, rights of citizenship, partnership, empowerment and choice, all set within a context of modernization. Table 2 shows the rationale for lay involvement embedded in the most significant policy initiatives since 1997 and Table 3 indicates the mechanisms to involve users that have been associated with the various initiatives.

Table 1.

Who is the user?

Table 2.

Rationale for lay involvement

Table 3.

Mechanisms of involvement

The introduction of PCGs/PCTs was intended, in principle, to strengthen public participation. Guidance has indicated that PCGs/PCTs should involve users in a variety of ways, including developing strategic plans for involving and communicating with patients and the public and providing sufficient resources and support to lay members. 10 The NHS organizations are also directed to involve patients and the public in clinical governance arrangements. However, findings from two successive cycles of the annual National Tracker Survey of PCGs/PCTs (1999–2000 and 2000–2001) (Download at http://www. npcrdc.man.ac.uk.), found the lay members' role in decision‐making to be peripheral and the effectiveness of PCGs' attempts to either inform or consult users to be poor, with little evidence that such consultations had had a major impact on decision‐making. 11 This is perhaps not surprising, as it is widely acknowledged that lay involvement is a complex and challenging task 1 , 12 and lay involvement in quality may pose particular challenges. For example, it has been observed:

`It is no surprise that measures of quality are producer‐led as the key professionals and their employing organizations are in possession of not only the data but also the means of processing the data to derive quality measures.' 13

However, while the concept of lay involvement remains challenging, in practical terms nowhere is this more likely to be so than in the case of health services, where several factors militate against the confident, assertive involvement of users. In spite of the information explosion that has occurred in recent years, the problem of `information asymmetry' 14 remains, as information can provoke strongly emotional responses in that it can be contradictory, confusing, complex, fear‐provoking and not always user‐friendly, resulting in lay people still requiring guidance in interpretation. In addition, faith in professionals persists and older patients and men still prefer not to seek out information. 15

Finding ways to integrate lay perspectives in quality measures has remained a low priority and may explain partly why user involvement in quality has been underdeveloped to date. 16 , 17 In a recent review of initiatives around patient and public involvement the author concluded that, despite the presence of radical ideas within these proposals:

`There is no explicit mention of the involvement of patients and the public in quality improvement.' 18

Lay involvement in clinical governance

Lay involvement is an intrinsic part of clinical governance policy, according to the government's guidance on implementing clinical governance:

`The driver for change must be the delivery of high quality clinical and cost‐effective services for patients. A clear aim must be the involvement of patients and the public in the decision‐making process.' 19

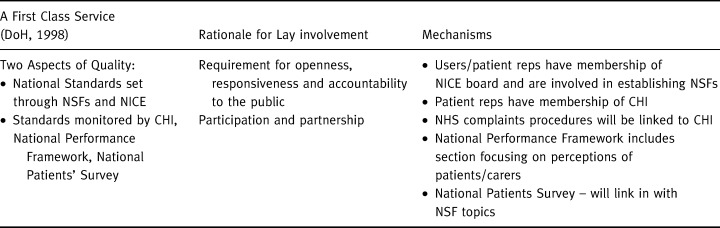

Table 4 sets out the rationale for lay involvement in clinical governance together with possible mechanisms for achieving them.

Table 4.

Lay involvement in clinical governance

While professional self‐regulation remains at the heart of clinical governance in the new NHS, The NHS. Modern, Dependable states this must sit alongside increased public accountability, a potentially critical ambiguity when policy is translated into practice at the PCG/PCT level:

`The government will continue to work with the professions, the NHS and patient representative groups to strengthen the existing systems of professional self‐regulation by ensuring that they are open, responsive and publicly accountable.' 20

Lay involvement in clinical governance in primary care

Within PCGs/PCTs, there are two principle ways in which lay participation in clinical governance may be effected: at Board level, through the key figure of the lay member and at grass roots, tapping into the PCG/PCT's constituency and involving users and local groups, as well as patients at GP surgeries.

At Board level

At Board level, the onus is on the whole Board to ensure `that the key requirements of public accountability, probity and public involvement are fully met through publicly transparent systems'. 21 However, genuine involvement of the lay member – which entails active, meaningful involvement – will be necessary before this can occur. Hogg & Williamson 22 have suggested that there are three models that explain the behaviour of lay members on health service committees: type 1, `supporters of dominant interests', who support professional interests; type 2, `supporters of challenging interests', who tend to support executive managers' interests and type 3, `supporters of repressed interests', who tend to take on the patients' interests against the dominant professional and managerial groups. This makes clear how appointment systems, terms of reference and accountability arrangements made by PCGs/PCTs in respect of lay members can play a big part in determining which of the three models will prevail.

Early findings from the National Tracker Survey suggest that lay involvement in PCG/PCT governance is poor at most levels and particularly with respect to clinical governance. 11 Lay Board members rated their influence on decision‐making as lower than that of the Chief Officer, Chair or GP Board members, 11 which raises questions about whether public viewpoints can re‐shape professional viewpoints. At the same time, lay members appear to be drawn from a very `safe' section of the public, which one may almost describe as the `professional' lay public. Data from the Tracker study regarding the background of lay members indicates that, of those in paid employment, 50% worked in the public sector, 46% had experience of working in the voluntary sector and 27% had worked within a Community Health Council (CHC).

Beyond Board level: PCG/PCT constituency and GP practice populations

Engaging the public in clinical governance locally, whether in on‐going consultations or for one‐off purposes, and including the general public as well as specific patients/user groups, would help to ensure that local priorities for action were relevant and appropriate to the people they are intended to benefit.

However, early indications are that user engagement of this kind is even less developed than lay member involvement in governance. The annual Tracker Survey, gauging the perceptions of CHCs, indicates that PCGs/PCTs have made little or no progress in their first 2 years with public consultation and have not consulted local people at all on three key areas for service development, including services for older people, coronary heart disease and mental health.

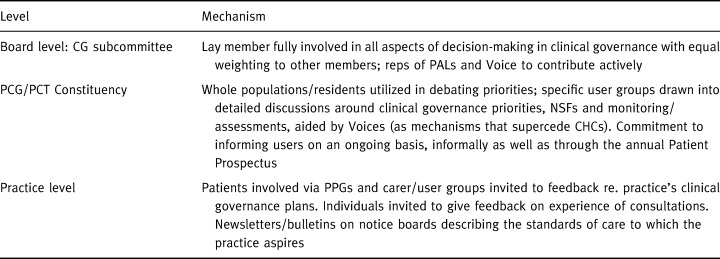

Table 5 displays the mechanisms that may be utilized for involving lay people at each of the levels described above.

Table 5.

Mechanisms for involving lay people in clinical governance within PCG/PCT constituencies

Aims and methods of this study

The data in this paper is based on the findings of the first stage of a 3‐year longitudinal study begun at the National Primary Care Research and Development Centre (NPCRDC) in August 2000. While the issue of incorporating lay people's views into health‐care decision‐making is one that is of relevance to many health‐care systems internationally who may be experimenting with ways of incorporating the user voice, this paper looks at lay involvement in the UK NHS and in one aspect of health‐care decision‐making in particular – that of clinical governance.

The NPCRDC study is being carried out in a purposive sample of 12 PCGs/PCTs selected to provide maximum variation in a range of characteristics including size, rurality and group or trust status. The PCGs/PCTs are being followed longitudinally to examine both the concept of clinical governance employed and approaches used to implement it, focusing on care provision for mental health and coronary heart disease as exemplars. One aim of the study is to investigate how clinical governance strategies differ in involving service users and the public in clinical governance. In particular, it has sought to explore how users' views are fed into clinical governance, the approach of general practitioners and other professionals to this and whether any changes have been made to services in response to users' views.

The data is based on semi‐structured interviews carried out with key stakeholders, including Lay Board members (n=12), Chief Executives (CEs) (n=12), Clinical Governance Leads (CG lead) (n=12) and Mental Health Leads (MH lead) (n=9). Interviews were carried out by members of the research team between August and December 2000. These were tape‐recorded and used to write case studies, adhering to an agreed common structure. Case studies, together with the original transcripts of the interviews and additional field notes, were then used as the basis for a thematic analysis. Themes were decided in discussion with all members of the team, each of whom had access to a full set of transcripts and case study materials, to ensure inter‐rater reliability.

We did not collect information directly from GPs: information about practice‐based lay involvement was collected at PCT level.

Findings

Board level: role of the lay member

Lay Board members across all PCGs/PCTs in our study perceive their role to encompass some of the following functions

• probity and accountability;

• to ensure that the PCT reflects the views of the locality;

• to ensure that PCT language is transparent and not too full of jargon;

• to ensure that there are opportunities for the public to understand the role of the PCT;

• to ensure PCT activities are advertised, and

• as a point of contact for local people.

In these varied activities, the lay members claim not to be representing the views either of users in general or of any particular constituency of users and to be acting as a `lay example' rather than a representative:

`The lay member doesn't actually represent anybody. You're there as a person who doesn't hold an office, basically. They assume that you will represent the public more than anything else, because that's the only view you've got but you're not mandated. The only view I'm mandated to give is my own.' (lay member, PCG C)

However, this exposes them to the same criticisms previously made of CHCs, namely that they are unrepresentative of interests other than those of the white, educated, able‐bodied middle‐class with sufficient leisure time. 23 This possibility is heightened by the application process for lay members, as one lay member explained:

`I was annoyed that they said this was meant for normal people in the queue at Tesco to fill in and you needed a Masters' degree to fill that application form in.' (site C)

`I am not required to represent a majority view, I am required simply to express my own view, which is not that of a health professional. And of course the danger is that after a couple of years that's precisely what you become.' (lay member, site E)

In Hogg & Williamson's classification, 22 one consequence of such an application procedure may be that lay members are less likely to be `supporters of repressed interests' (type III in their typology) than supporters of the medical profession or managers (types I and II).

Lay member involvement in clinical governance at Board level

In most sites, lay members have not been involved in setting clinical governance priorities, in some cases because they have been appointed late to the board, in others because they did not have membership of the clinical governance subgroup.

Across our sites, lay involvement with clinical governance was meant to be achieved by lay member attendance at clinical governance subgroup meetings and/or the CG lead's attendance at lay involvement subgroup meetings. However, in four sites there is no lay member representation on the clinical governance subgroup.

There is a view that National Service Frameworks, which set out the standards to be attained for clinical care, have done more to promote change than any pressure on the part of users themselves, who had previously identified the need for such change:

`The National Service Framework has done an awful lot to bypass the clinicians' barriers to change.' (lay member, site K)

`I get the impression that a lot of things in the National Service Framework, the users have identified what they wanted and the Trust and the Health Authority and the PCGs also identified that if they didn't do something about it, you know, they were going to continuously get back by the users saying we need change. So I think that even if National Service Frameworks hadn't come about … but National Service Frameworks may make them happen a bit quicker and may formalize things.' (site I)

Beyond Board level: involvement of `the public'

Involvement of the public may comprise two aspects: (a) Involvement of patients at general practice level and (b) Involvement of the general public within the PCG/PCT area, including the involvement of specific user groups in defined clinical governance agendas.

Involvement at general practice level

Across our sites there was some evidence of involvement of users in clinical governance at GP practice level but it was sparse and sporadic. For example, in one site the lay member explained:

`GP surgeries are planning to do a random survey on the spot of what patients think of some of the facilities that they have and what sort of care they're getting through the doctors.' (site H)

Such activity would be building on a weak foundation, as other research has shown that GPs are generally inexperienced at involving users. No more than half of the practices in any one area have established Patient Participation Groups while many PCGs/PCTs have as little as one or two.

One site (F) has made evidence of patient involvement an essential requirement of the practice audit for clinical governance. However, as the CE described, they have begun with `very, very limited expectations' and the requirement is restricted to the administering of a standard questionnaire about patient satisfaction and overall expectation of primary health‐care.

The wider public

The merits of lay involvement in clinical governance are acknowledged by the Board and Executive Committee members. As the Chief Executive of site J pointed out: `it's a key part of our philosophy'. However, as the lay member of the same primary care organization pointed out, although there is a commitment to dealing with the lay voice, `so far it doesn't mean anything'.

Indeed, this commitment to the concept of lay involvement, with very little action to back it up, is widespread among our sites. Ahead of the establishment of Voices[Link], much emphasis continues to be placed on CHCs as conduits for user involvement. The annual Tracker Study found that, in their second year of operation, PCGs/PCTs had consulted CHCs more than any other patient/user group (74.5% have consulted CHCs as compared with 17% consulting patients/ carers). As we have seen, an explanation for this might be the methodological difficulties surrounding the users. It was therefore unsurprising to find that lay members expressed consternation at the impending demise of CHCs:

`I have heard a lot of concern expressed both by the general public and obviously by the CHC that the new provisions as outlined will not provide the necessary independence that the CHC can offer.' (lay member, site D)

Across the case study sites, there were very few examples of user involvement in mental health or coronary heart disease and where it had occurred, it appeared to be superficial – in some cases, there was uncertainty on the part of the lay members as to whether or not it had occurred. In two PCGs there was involvement of users in devising the mental health strategy, building on historical precedents. In one PCG, the British Heart Foundation had been involved in devising the CHD strategy, although the impact of their involvement was unclear to the lay member.

Where user forums had been established in one PCG, these were organized mainly to enable clinicians to give information to users. Some `user surveys' had been completed. However, the effects of such activity were described by both lay and professional members as superficial and there were no examples of any wider public input into setting clinical governance priorities.

Barriers to lay involvement

Several barriers to lay involvement have been identified by interviewees in our study, including organizational upheaval, structural factors within the PCG/PCT, (in particular the relationship between the Board and the Executive Committee), the complexity of clinical issues, methodological problems around how to do user involvement, tensions around professional accountability (that is, between professional control of clinical quality and the policy of lay participation) and the prerequisite for a cultural change to take place organizationally.

The demands of organizational change have delayed the introduction of lay involvement, as it has been perceived to be of a lower priority than other issues, such as getting GPs themselves on board with the changes.

One lay member explained that the first priority in the context of organizational upheaval was to work with GP practices, justifiably so, he felt:

`I don't think we were trying in any way to ignore, far from it, user perspectives, but we felt it was an important part of confidence building that the practices were involved with clinical governance.' (site F)

Another lay member pointed out that things have been slow because of the NHS Plan and pressures to move to PCT status and felt the organization is `treading water' at the moment (site K) (although as user involvement is fundamental to the NHS Plan and moves to Trust status the lack of lay involvement should be viewed with some anxiety by policy makers).

The structure of the PCG/T is significant in this regard. The relationship between the Board and the Executive Committee is left to individual organizations to determine. There is a view held by several lay members that, by way of contrast with PCGs, the PCT structure sidelines lay members through its separate executive committee and board[Link]. The difference between lay membership within the PCG and PCT structure is pithily summarized by the following lay member:

`Last year I was part of the. board which is now the executive committee … but essentially it's the same people and now I'm a step further away on the lay board and that's a bit of a strange situation for me … we're on the edge of decision‐making and I'd like to see us involved more fully…' (lay member, site H)

On the other hand, we find the opposite view expressed by one member, interestingly of a PCG (who has not yet experienced the effects of the changes in moving to Trust status in practice):

`When we become a PCT and there is a Board of five non‐execs and a lay chairman, there is a greater possibility of getting public opinion because those six lay people will be able to bring with them anyway the public opinion because they are lay members and people like me will be able to bring more information.' (site L)

Where, in one case, the lay member did play an important role, with involvement in a wide range of board activities, he felt that this was a result of the goodwill of the individual professional members rather than signifying that the role of the lay members was an inherently strong and powerful one:

`I think you're a bit dependent on the collective attitude of your doctors. If the doctors are there, determined to do their best and live with everybody and bring everyone in, then I think it works in that way. If the doctors are there to fight their own corners, only for own practices or only for their own interests then I don't think it does work.' (lay member, site E)

At subcommittee level, in some PCGs/PCTs there appears to be a large amount of lay activity (for example, in HiMP committees, public involvement committees called by varying names) with little co‐ordination between groups or overview of their disparate activities. One of the lay members who is not on the PCG's clinical governance subgroup thought that, while the PCG might well have done something on user involvement, she is not aware of it because: `when you're in a subgroup you go about your business on that subgroup and that's it' (site C). She identifies good pockets of activity, for example an active teenage group involved with one of the doctors commenting on what is helpful with respect to teenage pregnancies. But the impact of such activity was thought to be limited:

`Because everybody like myself actually has another job, several jobs usually. And so you've not got as much time as you like to put into it and I felt if we'd had one person devoted to this kind of thing that would have been good.' (site C)

Another `barrier' to full lay involvement lies in the complexity of clinical/professional issues. One lay member explained how she had experience of having been on the CHC, which helped her both in understanding the business at hand and in having the necessary confidence to ask questions when she did not; however:

`There are an awful lot of people I could imagine would have just thought after a few weeks, “Well, I think I'll just go away and shrivel up.”' (lay member, site C)

In addition, lay members may be in a disadvantageous position because they require training in aspects that professionals are thoroughly acquainted with:

`There are some things that we have to be advised on because we don't know the ins and outs of it ourselves…' (lay member, site H).

This leads to inhibition if not outright paralysis in terms of the ability to make a contribution.

`I know damn well I don't know too much about CHD, other than what I see or what I read in the papers, so you find the people who are not clinicians do tend to defer to the doctors and health visitors and the nurses … how can you have a proper opinion, when you don't even understand the drugs the people are being given, you don't understand the regimes at all?' (lay member, site C)

Moreover, she does not see how this could be obviated

`I don't think you can do anything about it because they are doing it daily and you are coming in once a fortnight to look at the agenda and have a view and you tend to be led by their expert opinion.' (site C)

She likens this to the situation of accountants talking about financial matters `and how can you gainsay them?'

Another factor, which militates against lay members making an important contribution, is that of the time‐limited nature of their contribution:

`With the time constraints of only five days a month, it's impossible I think for lay people to really get to grips with it.' (lay member, site H)

The above lay member feels it should probably be a full‐time post.

Involving members of the public is a complex issue and one that professional members find particularly challenging methodologically:

`They say, “Yes, that's entirely right, conceptually, but how the hell do we do it?”' (CE, site F)

Indeed, the question of `how to do it' has had a paralysing effect on activity in this area, particularly the search for the elusive `typical user', which thinking implicitly assumes role of users to be a representative one. As the Mental Head Lead of one PCG/PCT explained:

`Around the city, when we've looked at, we've looked to find suitable people to be user representatives, the ones that have tended to come forward are actually long‐term secondary sector, chronic mental health problem users. Who aren't that typical in fact, of the average person that has contact with mental health services (whose) needs are not going to be identified by someone who's representing chronic recurrent psychotic illness.' (MH Lead, site J)

Beyond the mechanics of involving users are broader philosophical conundrums, specifically how to reconcile antagonistic or clashing viewpoints and perspectives. For example, the difference between lay and professional viewpoints in terms of quality is summarized by this view, expressed by a lay member in site C:

`I think anything in a doctor's practice affects how a customer kind of gets treated. Really it is to do with clinical governance and quality. But I'd get so broad a definition that you wouldn't be able to do anything with it. I think it would be unworkable. So maybe they're right to narrow it down. And I think maybe that's part of being lay. That you just do see everything bigger. Whereas they have to see it really in quite narrow terms.'

One lay member pointed out, reiterated by several other lay members, that they had concluded that it was important to focus on finding out answers to discrete questions rather than spreading their net too widely:

`I think the main overall idea we came down to was, you couldn't have mass consultation about anything under the sun. What you had to do was identify what the specific problem or issue was and work out what was appropriate in that case.' (lay member, site C)

Another lay member (site K) complained that user involvement so far tends to be either the CHC ‘sort of … easy proxy' or large, almost Health Authority‐size consultations.

In addition, the culture of the medical profession was said to need change, as explained by one lay member:

`The doctors themselves are scared of public opinion … they think the public are going to complain all the time.' (lay member, site L)

Consequently, while some lay members are confident that lay involvement will increase in the future, they feel that this will come about through a necessarily slow and thorough cultural change.

`It's a sort of culture thing … it can't just be sustained by a few people trying to do it locally. It's got to be a whole organisational thing.' (lay member, site K)

Discussion

Despite the acknowledgement by all respondents of the importance of lay involvement as an issue for PCGs/PCTs, it has been slow to get off the ground in primary care governance generally and clinical governance in particular. The role of lay members within the PCG/PCT lacks clarity and their contribution to clinical governance, both at the outset in setting priorities and with respect to implementing and monitoring change, remains low. Mechanisms for involving users more widely are in their very early stages of development and involvement in clinical governance activities is patchy and relatively superficial. In terms of our framework, in Table 4, while some of the mechanisms are in place, few of them are being employed actively in the ways suggested in column 2.

Throughout the paper we have given certain explanations as to why user involvement is so underdeveloped in clinical governance. Arising naturally from this, we may point to several modifications which, if they are made at the levels of national policy, PCTs and individual GP practices, may improve the particular model of user involvement currently being utilized. At the national level, there is a need for quality measurements to be devised which combine and integrate both professional and lay perspectives on quality. While existing National Service Frameworks attempt to do this, they do not as yet go far enough. At PCT level, there needs to be greater clarification, probably defined at policy level, of the role of the lay member. The wider public could be involved in setting as well as discussing clinical governance priorities and patients involved more consistently in quality discussions within GP practices, including feed back on individual consultations.

But there is a more fundamental reason for the gap between rhetoric and reality and this may be because the model of user involvement promoted in current policy is flawed. We must look deeper than cosmetic modifications to this model if we are to witness any real engagement of users in decision‐making, including quality. Before this can occur, there is a prerequisite for a more equal partnership between professionals and patients to evolve which will enable the involvement of lay people to occur at all levels, but beginning at the micro level. While this is beyond the scope of the current paper, we can make some suggestions as to its broad outline. In policy terms, shared decision‐making is integral to the messages contained within the NHS Plan 21 and the Expert Patient. 24 For example, the Expert Patient talks about `transformation' and the `ending of an era' in which the `patient as passive recipient of care' is being replaced by a new relationship:

`In which health professionals and patients are genuine partners seeking together the best solution to each patient's problem, one in which patients are empowered with information and contribute ideas to help in their treatment and care.' 24

A similar transformation needs to occur within the arena of quality in primary care. If the committee model is used, lay voices must be given a stronger role, which may entail, for example, equal numbers vis‐à‐vis professionals. However, it will be more beneficial to replace the committee model, in which user involvement is perceived to begin and end with the lay member sitting on the Board, with other consumerist mechanisms. True shared decision‐making has the potential to be revolutionary, both for user involvement and for the NHS in general, as current policy recognizes but in order for this to occur, the lay person will require better information and greater support in using that information than is currently available. In this process, valuable lessons can be drawn from the experience of other countries; for example, the Foundation for Accountability Centre (FACCT) in the USA works with professional bodies, research agencies and patients to develop quality measures. 15 This supportive role will be one that Voices may be best equipped to fulfill.

Footnotes

Voices – statutory bodies which will strengthen and facilitate the public voice, citizen as well as patient and which will operate at Strategic Health Authority level.

Each PCT comprises a Board and an Executive Committee. The Board comprises more lay than professional members (five lay members and a lay chair with only three professional members). The Executive Committee, by contrast, has a majority of professional members (up to 10, comprising up to seven GPs) and a chair chosen by these professional members. The role of the PCT Board is to provide strategic oversight but the Executive Committee is responsible for the daily management of the PCT, including developing and initiating service policies, investment plans, priorities and projects to be delivered by the PCT.

References

- 1. NHSE . In the Public Interest, Developing a Strategy for Public Participation in the NHS. Leeds: NHSE, 1998.

- 2. Allen P. Accountability for clinical governance: developing collective responsibility for quality in primary care. British Medical Journal, 2000; 321 : 608–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Day P, Klein R. Accountabilities: Five Public Services London: Tavistock, 1987: 19.

- 4. Colin‐Thome D. First aid for local health needs. Demos, 1996; 9 : 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robinson B. Primary managed care: the Lyme alternative. In: Meads G (ed.) Future Options for General Practice: Primary Care Development. Oxford: Radcliffe Press, 1996.

- 6. Barnes M, McIver S. Public Participation in Primary Care Birmingham: Health Services Management Unit, 1998.

- 7. Agass M, Coulter A, Mant D, Fuller A. Patient participation in general practice: who participates? British Journal of General Practice, 1991; 41 : 198–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Audit Commission . What the Doctor Ordered: A Study of GP Fundholders in England and Wales. London: HMSO, 1996.

- 9. National Health Services Executive . Towards a Primary Care Led NHS London: NHSE, 1995.

- 10. Department of Health . Primary Care Trusts: Establishment, the Preparatory Period and their Functions 2000, Download at www.doh.gov.uk.

- 11. Pickard S, Smith KA. Third Way for Lay involvement: what evidence so far? Health Expectations, 2001; 4 : 170–179.DOI: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2001.00131.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Public Administration Committee . Innovations in Citizen Participation in Government: Minutes of Evidence London: House of Commons, 1999.

- 13. Hart M. Incorporating outpatient perceptions into definitions of quality. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1996; 24 : 1234–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shackley P, Ryan M. What is the role of the consumer in health care? Journal of Social Policy, 1994; 23 : 517–541. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kendall L. The Future Patient, 2001, London: IPPR.

- 16. Rosen R. Improving quality in the changing world of primary care. British Medical Journal, 2000; 321 : 551–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelson M, Redpath L. Promoting user involvement in clinical audit. surveys of audit committees in primary and secondary care. Journal of Clinical Effectiveness, 1996; 1 : 14 14. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lakhani M. Patient and public involvement in quality improvement. The Journal of Clinical Governance, 2001; 9 : 165–166. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Department of health . A First Class Service: Quality in the New NHS. London: HMSO, 1998: 76.

- 20. Department of Health . The NHS: Modern. Dependable. London: HMSO, 1997 para 7.15.

- 21. Department of Health . The NHS Plan London: HMSO, 2000.

- 22. Hogg C, Williamson C. Whose Interests do lay people represent? Towards an understanding of the role of lay people as members of committees. Health Expectations, 2001; 4 : 2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pickard S. The future organisation of community health councils. Social Policy and Administration, 1997; 31 : 274–289. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Department of Health . The Expert Patient: A new approach to Chronic Disease Management for the 21st century, 2001, download at http://www.doh.gov.uk.