Abstract

Objective To develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a breast cancer prevention decision aid for women aged 50 and older at higher risk of breast cancer.

Design Pre‐test–post‐test study using decision aid alone and in combination with counselling.

Setting Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Clinic.

Participants Twenty‐seven women aged 50–69 with 1.66% or higher 5‐year risk of breast cancer.

Intervention Self‐administered breast cancer prevention decision aid.

Main outcome measures Acceptability; decisional conflict; knowledge; realistic expectations; choice predisposition; intention to improve life‐style practices; psychological distress; and satisfaction with preparation for consultation.

Results The decision aid alone, or in combination with counselling, decreased some dimensions of decisional conflict, increased knowledge (P < 0.01), and created more realistic expectations (P < 0.01). The aid in combination with counselling, significantly reduced decisional conflict (P < 0.01) and psychological distress (P < 0.02), helped the uncertain become certain (P < 0.02), and increased intentions to adopt healthier life‐style practices (P < 0.03). Women rated the aid as acceptable, and both women and practitioners were satisfied with the effect it had on the counselling session.

Conclusion The decision aid shows promise as a useful decision support tool. Further research should compare the effect of the decision aid in combination with counselling to counselling alone.

Keywords: patient decision aids, breast cancer prevention, patient participation, health education, decision‐making, decision support techniques

Introduction

Women at increased risk for breast cancer want to learn about their risk of breast cancer, obtain information about the options available to lower their risk, and develop decision‐making skills. 1 Tamoxifen, as a chemopreventive agent, is an option for women at higher risk of breast cancer. However, the efficacy of tamoxifen in three breast cancer prevention trials has been inconsistent. 2 , 3 , 4 One large trial demonstrated a 45% reduction in the incidence of breast cancer, but two other trials showed no benefit. In addition, the side‐effects associated with tamoxifen include uterine cancer, cataracts, and thromboembolic events. The American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines recommend that women should consider the harms and benefits of tamoxifen when deciding about accepting treatment. 5 Given its potential benefits and serious harms, women are likely to experience difficulty making this decision. Support for decision‐making may be provided through counselling supplemented by decision aids.

The Cochrane Collaboration defines decision aids as ‘interventions designed to help people make specific and deliberative choices among options by providing (at a minimum) information on the options and outcomes relevant to the person's health status’ (ref. 6, p. 67). A systematic review of 24 trials evaluating patient decision aids found that decision aids were better than usual care at improving knowledge, creating realistic expectations of benefits and harms, reducing decisional conflict, and enhancing participation in decision‐making. 7 Decision aids had no effect on satisfaction and anxiety, and a variable impact on the actual decision. None of the studies evaluated decision aids for breast cancer prevention. Moreover, there has been little evaluation of: (1) practitioners’ views of decision aids and their effect on counselling; (2) patient distress from perceived risk; and (3) intentions to change life‐style behaviour. 6 , 7 , 8

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a decision aid for women aged 50 and older who are at increased risk of developing breast cancer and are preparing for professional counselling about risk reduction options.

Methodology

The decision aid was developed and evaluated in three stages. In the first stage, the decision aid was developed and reviewed by expert practitioners. The second stage was a pre‐test–post‐test evaluation of the decision aid alone with a convenience sample of volunteers who were at increased risk for breast cancer. The third stage involved a pre‐test–post‐test evaluation of the decision aid combined with counselling for women attending a breast cancer risk assessment clinic. Ethics approval was obtained from The Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board, Ontario, Canada.

Development

The five standardized steps used for the development of the decision aid were: (1) identify the need for the decision aid; (2) determine its feasibility; (3) clarify the objectives of the decision aid; (4) choose a theoretical framework to guide its development and evaluation; and (5) select methods to support decision‐making. 6

The need for a decision aid was confirmed by establishing that the decision about tamoxifen is common and focused on important outcomes. 5 , 9 , 10 About 21% of American women are defined as ‘higher risk’, that is, having cumulative risk factors (e.g. family history, early menses, advancing age, breast biopsies, and delayed age at birth of first child) resulting in a 1.66% or greater 5‐year risk of breast cancer. 11 , 12 Moreover, the evidence on its efficacy is inconsistent and the choice involves making value tradeoffs between benefits and harms. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 From a previously published needs assessment, we ascertained that women aged 50 and older who are considering options to lower their risk of breast cancer need: (a) a realistic understanding of their personal risk; (b) accurate information on healthy life‐style practices, breast screening guidelines, benefits and harms of tamoxifen, and chemoprevention clinical trials; (c) help considering the opinions of others; (d) clarification of their personal values that factor into the decision; and (e) guidance in making a decision. 1 To help address these decision support needs, women require access to practitioners for counselling with supporting educational resources. An available Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool 12 assesses risk, but provides little balanced information on the outcomes of tamoxifen and no information on other strategies. There are no existing patient decision aids focused on this issue. 13

The development of a breast cancer prevention decision aid was determined to be feasible given the research evidence on the prevention options, 2 , 5 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 the availability of a risk assessment tool, 12 access to expert practitioners, and a setting to disseminate the decision aid.

The objective of the decision aid was to help higher‐risk women, aged 50 and older considering options to lower their risk of breast cancer, to prepare for consultation with a breast health practitioner, and to make a high‐quality decision about the use of tamoxifen as a chemopreventive agent. A high‐quality decision was defined as informed, consistent with personal values, acted on, and one in which the woman expresses satisfaction, not only with the decision itself but also with the process used to reach it. 25

The Ottawa Decision Support Framework is an evidence‐based theoretical framework that was used to guide the development and evaluation of the decision aid (see Table 1). 8 , 25 Several other frameworks for assessing and supporting clients’ decision‐making have also been developed. 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 The Ottawa Framework was chosen because of its fit with the decision support needs of higher‐risk women, focus on determinants of decisions that can be addressed by interventions, and previous validation in similar circumstances.

Table 1.

Ottawa Decision Support Framework (reprinted with permission of the author)

| Assess needs (determinants of decisions) | Provide decision support | Evaluate |

|---|---|---|

| Perceptions of the decision | Provide access to information | Decision‐making |

| Knowledge | Health situation | Reduced decisional conflict |

| Expectations | Options | Improved knowledge |

| Values | Outcomes | Realistic expectations and norms |

| Decisional conflict | Others’ opinions and choices | Clear values |

| Stage of decision‐making Predisposition towards options | Re‐align expectations of outcomes | Agreement between values and choice |

| Clarify personal values for outcomes | Implementation of chosen option | |

| Perceptions of others Perceptions of others’ opinions and practices | Provide guidance or coaching in: Steps in decision‐making | Self‐confidence and satisfaction with decision‐making |

| Support | Communicating with others | Outcomes of decision |

| Pressures | Handling pressure | Persistence with choice |

| Roles in decision‐making | Accessing support and resources | Improved quality of life Reduced distress |

| Resources to make decision | Reduced regret | |

| Personal | Informed use of resources | |

| Previous experience | ||

| Self‐confidence | ||

| Motivation | ||

| Skills in decision‐making | ||

| External | ||

| Support (information, advice, emotional, instrumental, financial, professional help) from social networks and agencies | ||

| Characteristics | ||

| Client: age, sex, marital status, education, occupation, culture, locale, medical diagnosis and duration, health status | ||

| Practitioner: age, sex, education, specialty, culture, practice locale, experience, counselling style |

The development team selected several decision support methods for the decision aid. These included providing information on the clinical problem, options, and outcomes with tailored probabilities; explicit values clarification; examples of how other women made their decision; and guidance in deliberation and communication of their decision.

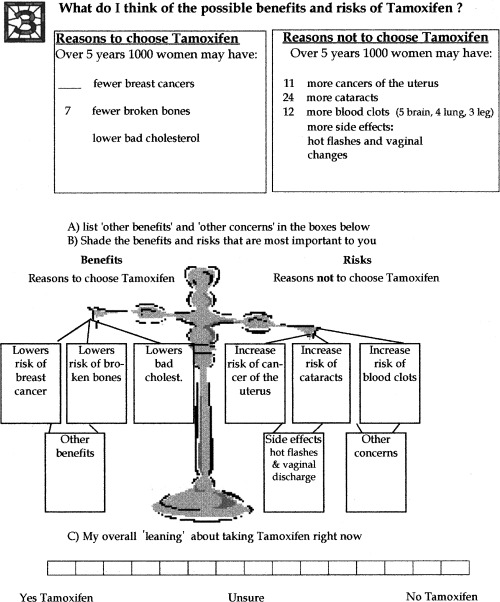

Expert review

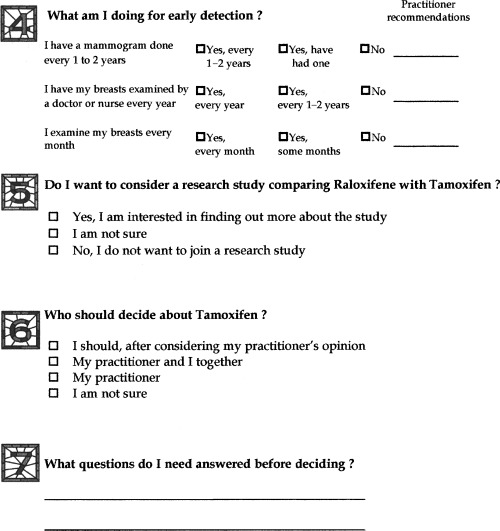

A panel of expert practitioners drafted the decision aid from January to August 1999. The panel included two medical oncologists, a breast surgeon, a breast health advanced practice nurse,* and an expert in evaluation of decision aids. The resulting decision aid is a self‐administered audio‐guided booklet and personal worksheet ( Fig. 1). The 24‐page illustrated booklet provides evidence‐based information on breast cancer, its risk factors, and options for women at higher risk of breast cancer including healthy life‐style practices, more intense breast cancer surveillance, tamoxifen, and a chemoprevention clinical trial. Although, the main decision profiled in the decision aid is whether or not to take tamoxifen, the other options provide women with additional choices.

Figure 1.

Personal worksheet.

The 35‐min audiocassette, narrated by an age‐appropriate female actor, guides the reader through the booklet with a musical sound signalling the reader to turn the page. The personal worksheet provides individualized breast cancer risk information and walks the reader through seven steps in decision‐making. It includes space to respond to checklists, to identify personal preferences, and to write down questions. The worksheet is designed to facilitate communication between the women and their practitioners. To enhance credibility, a list of the expert reviewers and references supporting the evidence were provided. The decision aid is available at the Ottawa Health Research Institute website at www.ohri.ca. Follow the links on the site to the Ottawa Health Decision Centre (OHDeC).

Pre‐test–post‐test of the decision aid alone

The decision aid was evaluated on a convenience sample of 10 female volunteers at increased risk for breast cancer. The purpose was to ensure that the decision aid format was acceptable, the information presented clearly, and completion of the evaluation tools feasible. The participants completed a questionnaire before and immediately after using the decision aid. The questionnaire elicited: acceptability of the decision aid, decisional conflict, knowledge, expectations of outcomes, and decision predisposition.

A convenience sample of women who met the following inclusion criteria participated: (a) female aged 50–69; (b) 1.66% or higher 5‐year risk of breast cancer; (c) able to read and speak English; (d) no personal history of breast cancer; (e) no prophylactic mastectomy; (f) no prior history of cancer within the past 10 years; and (g) a performance status that did not restrict normal activity for a significant portion of each day. After confirming eligibility, participants signed a consent form.

Pre‐test–post‐test of the decision aid combined with counselling

The decision aid was next evaluated with a convenience sample of 17 women at increased risk for breast cancer. We used a pre‐test–post‐test design with measures taken at four time‐points for the women (baseline, after using the decision aid, within a week after counselling, and 2 months after counselling) and one time‐point for health practitioners (after counselling). Patient baseline data included decisional conflict, knowledge, expectations of outcomes, decision predisposition, intention to make life‐style changes, and psychological distress. The acceptability data were collected after using the decision aid. Within a week following counselling, data were collected on all the baseline measures and satisfaction with preparation for counselling. Then, 2 months later, data was collected on life‐style changes and, for those undecided about tamoxifen, whether or not a decision had been made. Practitioner satisfaction with women's preparation for counselling was measured after the counselling session. Eligibility criteria were identical to those for the earlier evaluation and, in addition, women required a referral to the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment clinic at the Ottawa Regional Women's Breast Health Centre of The Ottawa Hospital. Eligible women were invited to participate in the study, when they were notified of their appointment at the clinic.

Two weeks prior to their appointment, the research nurse contacted women who agreed to participate to confirm their eligibility and arrange a 30‐min home visit. Once informed consent was obtained, women completed a 15‐min baseline questionnaire. The decision aid and acceptability questions were provided with instructions to use the decision aid and complete the questions before their clinic visit.

At the clinic, women received counselling from an advanced practice nurse and one of four physicians (two medical oncologists, two breast surgeons). During their visit, the women were encouraged to share their personal worksheet, ask questions, and discuss any concerns.

Outcome measures

Self‐administered questionnaires were used to elicit decisional conflict, knowledge, expectations of outcomes, decision predisposition, intention to make life‐style changes, psychological distress, satisfaction, decision predisposition, and acceptability of the decision aid. All measures were evaluated before and after the intervention except acceptability and satisfaction that were only evaluated after the intervention. Demographic data were also collected on the baseline questionnaire.

The acceptability of the tool was assessed using open‐ and closed‐ended questions. Closed‐ended questions elicited feedback on amount, length, clarity, and helpfulness of the information, degree to which the participant was upset by what they learned, whether the information was presented in balanced manner, and whether or not they would recommend it to others. These questions were based on an acceptability questionnaire developed by the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making to evaluate their decision support programmes. 33

The participant's level of decisional conflict was measured with the 16‐item Decisional Conflict Scale. 34 The test–retest and α coefficients for this measure exceed 0.81. The measure is sensitive to change 25 , 35 , 36 and discriminates between different decision support interventions. 37 , 38

The participant's knowledge was assessed using a 27‐item questionnaire about life‐style options and the benefits and risks of taking tamoxifen. The response categories for the questions (true, false, or unsure) were coded as correct or incorrect. Total scores ranged from 0 to 100% correct. Items in the questionnaire were reflective of the information contained within the decision aid and considered essential for informed decision‐making. The content validity was established with the expert development panel. Knowledge tests used in the evaluation of other decision aids had good internal consistency, discriminated between interventions, and were sensitive to change. 25 , 35 , 36 , 37

Personal expectations of disease (breast cancer, uterine cancer, and blood clots) within the next 5 years with and without tamoxifen were elicited by asking each woman to quantify her risk. The possible responses were broken down into 29 groupings that ranged from 0 out of 1000 women with risk factors similar to themselves to 1000 out of 1000. The answers were rated as accurate, underestimated risk, or overestimated risk. The score for realistic expectations was the percentage of accurate responses out of six questions. Test–retest coefficients for this type of measure exceed 0.80 and the scales are sensitive to change and discriminate between interventions. 25 , 37 , 38

The participant's decision predisposition was measured by asking them to mark along a 15‐point scale anchored by not taking tamoxifen at one end and taking tamoxifen on the other, with unsure in the centre. Their decision was also elicited with a direct choice question (accept tamoxifen, decline tamoxifen, or remain undecided) and reasons for the choice were solicited. The test–retest reliability coefficients of these types of measures exceed 0.90, are correlated to personal values and expectations, and are sensitive to change. 39

The participants’ current life‐style practices (e.g. level of physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake, body weight, and alcohol intake), as well as their intentions to improve these life‐style practices, were also measured. The intention to improve life‐style practices was measured using a seven‐point scale that ranged from extremely likely to extremely unlikely, with not sure in the centre.

The 15‐item Impact of Event Scale was used to assess the psychological distress associated with being at higher risk of breast cancer. 40 Participants were asked for their level of agreement with statements of intrusiveness or avoidance of thoughts, feelings, or situations on a four‐point scale ranging from not at all to often. The possible scores ranged from 15 (low distress) to 60 (high distress). The scale's authors administered it immediately before and after therapy and found it to have good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.86) and test–retest reliability (0.87). As well, this scale has been found to discriminate between women who received breast cancer risk counselling and those who did not. 41

Participants’ and practitioners’satisfaction with preparation for the visit at the clinic was assessed using nine and eleven questions respectively, rated on a five‐point scale ranging from 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction). Patient and practitioner versions of the scale have high internal consistency (α > 0.90). 42

Data analysis

Data were entered and analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows 7.5, 1996). Quantitative data were coded numerically and entered into the data file. All data were checked twice at entry and verified on printouts. In order to detect changes between baseline and post‐intervention measures, Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed ranks test was used for interval scaled measures and McNemar's test for change was used for discrete measures. The responses for acceptability, satisfaction, rationale for their decision, and demographics are reported using descriptive statistics.

Sample size

The primary outcome for this study was decisional conflict. The estimated sample size was calculated based on the paired t‐test for comparing the means of the outcome ‘decisional conflict’ measured before and after the intervention. For a level of significance α = 0.05, power (1 – β ) = 0.80, a standard deviation of 0.6, and a correlation between pre‐ and post‐test scores of 0.80, the sample size was estimated at 17 to detect a difference of 0.3 in the decisional conflict score, out of a possible score of one to five. Therefore, the effect size was 0.5, which Cohen defines as a ‘medium’ effect size that would be apparent to an intelligent viewer. 43 This effect size in the decisional conflict scale is clinically important because it is commonly observed between those who make versus those who delay decisions. 38

Results

Pre‐test–post‐test of decision aid alone results

Ten women participated in the decision aid alone evaluation conducted from August to September 1999. The participants varied in their age, marital status, primary language, education, and risk of developing breast cancer (see Table 2). The typical participant was 60 years old, married, Caucasian, English‐speaking, had post‐secondary education, a mother with breast cancer, and a 2.8% median 5‐year risk of breast cancer.

Table 2.

Summary of demographic characteristics of participants at baseline

| Decision aid only (n = 10) | Decision aid and counselling (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | Median 59.5 (range 50–67) | Median 55.0 (range 49–66) |

| 50–54 | 2 | 8 |

| 55–59 | 3 | 6 |

| 60–64 | 4 | 2 |

| 65–69 | 1 | 1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married, common law | 8 | 15 |

| Widowed | 1 | 0 |

| Divorced, separated | 1 | 2 |

| Primary language spoken/read | ||

| English | 7 | 14 |

| French | 3 | 3 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 2 | 2 |

| Post‐secondary | 8 | 15 |

| Age at first menses (years) | Median 12.0 | Median 12.0 |

| 10–11 | 3 | 3 |

| 12–14 | 7 | 14 |

| Age at birth of first child | Median 26.0 | Median 24.0 |

| No children | 1 | 2 |

| <30 | 7 | 13 |

| ≥30 | 2 | 2 |

| Number of first degree relatives | ||

| 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 7 | 11 |

| ≥2 | 1 | 5 |

| Number of breast biopsies | ||

| 0 | 8 | 11 |

| 1* | 1 | 3 |

| 2* | 1 | 3 |

| 5‐year risk of breast cancer (%) | Median 2.8 | Median 2.6 |

| 1.8–2.0 | 2 | 4 |

| 2.1–2.5 | 2 | 4 |

| 2.6–3.0 | 3 | 2 |

| 3.1–4.0 | 2 | 3 |

| 4.1–5.0 | 1 | 1 |

| 5.1–6.0 | 0 | 2 |

| 6.1–7.5 | 0 | 1 |

| Desired role in decision‐making | ||

| Active | 8 | 10 |

| Shared | 2 | 6 |

| Delegate to physician | 0 | 1 |

*Results all normal.

On average, it took 45 min to review the audio‐guided booklet and complete the personal worksheet. Eight of 10 women rated the amount of information as just right with the other two wanting a little more information. The ratings for the length of the tool were equally positive, with only one woman who rated it as a little too long. All women said either everything or most things were clear and none of the 10 women were upset by the information. Six women rated it as completely balanced, three considered it slanted toward tamoxifen, and one thought it was slanted against tamoxifen. All participants found the decision aid helpful in making the decision and all said they would recommend it to other women.

The measurement tools were well accepted as evidenced by the completion rate on the questionnaires. There was only one missing response for one participant with a possible 53 responses per pre‐test questionnaire and 52 responses per post‐test questionnaire. When pre‐test–post‐test responses were compared, there was a statistically significant improvement (P < 0.05) in knowledge scores (see Table 3) and realistic expectations of outcomes (see Table 4). The largest improvement in decisional conflict was in the informed sub‐scale (see Table 5). At baseline, one participant was leaning toward tamoxifen, three were leaning toward no tamoxifen, and six were unsure. After using the decision aid, four of the women who were unsure made the decision to decline taking tamoxifen and two remained unsure. Reasons cited for not choosing tamoxifen were concern about the risk of uterine cancer and blood clots.

Table 3.

Knowledge scores before and after decision support

| Number of respondents who accurately answered the questions | Decision aid only (n = 10) | Decision aid and counselling (n = 17) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐test | Post‐test | Pre‐test | Post‐test | |

| 1. Options for lowering my risk of breast cancer are: | ||||

| Exercising regularly | 6 | 10 | 16 | 17 |

| Having a healthy weight | 9 | 10 | 16 | 17 |

| Drinking more alcohol | 9 | 10 | 14 | 17 |

| Eating five or more fruit and vegetables a day | 7 | 10 | 15 | 17 |

| Eating foods higher in fibre | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Eating foods higher in fat | 8 | 8 | 15 | 15 |

| Taking tamoxifen every day | 1 | 7 | 4 | 12 |

| 2. Tamoxifen can be given: | ||||

| To women with breast cancer | 8 | 10 | 10 | 16 |

| To healthy women who have a higher risk of breast cancer | 6 | 10 | 14 | 17 |

| For 5 years | 6 | 10 | 5 | 17 |

| 3. Benefits of taking tamoxifen for healthy women who are at higher risk of breast cancer are: | ||||

| Lowers chance of breast cancer | 5 | 10 | 10 | 17 |

| Lowers chance of uterus cancer | 3 | 10 | 4 | 17 |

| Lowers chance of blood clots | 4 | 10 | 1 | 16 |

| Lowers chance of osteoporosis | 2 | 10 | 4 | 17 |

| Lowers blood levels of ‘bad’ cholesterol | 1 | 10 | 0 | 15 |

| Lowers chance of cataracts | 1 | 9 | 1 | 17 |

| 4. Risks of taking tamoxifen for healthy women who are at higher risk of breast cancer are: | ||||

| Increases chance of breast cancer | 4 | 10 | 10 | 15 |

| Increases chance of uterus cancer | 3 | 10 | 4 | 17 |

| Increases chance of blood clots | 3 | 10 | 2 | 16 |

| Increases chance of osteoporosis | 1 | 10 | 3 | 17 |

| Increases blood levels of ‘bad’ cholesterol | 1 | 10 | 1 | 16 |

| Increases chance of cataracts | 1 | 10 | 0 | 17 |

| 5. Some side‐effects of tamoxifen are: | ||||

| Hot flashes | 5 | 10 | 7 | 17 |

| Insomnia | 0 | 5 | 14 | 6 |

| Breast tenderness | 0 | 4 | 14 | 7 |

| Weight gain | 0 | 5 | 1 | 10 |

| Vaginal dryness | 3 | 10 | 3 | 14 |

| Median score (% accurate) | 40.5% | 89% | 41% | 89% |

| Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed ranks test | z = −2.8 (P = 0.01) | z = −3.6 (P < 0.001) | ||

Table 4.

Accuracy of expectations of outcomes before and after decision support

| Number of respondents who | Decision aid alone (n = 10) | Decision aid and counselling (n = 17) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| accurately identified their 5‐year risk | Pre‐test | Post‐test | Pre‐test | Post‐test |

| Without tamoxifen | ||||

| Breast cancer | 0 | 8 | 0 | 13 |

| Uterine cancer | 3 | 8 | 7 | 12 |

| Blood clots (brain, lungs, deep leg veins) | 0 | 7 | 1 | 11 |

| With tamoxifen | ||||

| Breast cancer | 0 | 6 | 0 | 9 |

| Uterine cancer | 2 | 8 | 6 | 13 |

| Blood clots (brain, lungs, deep leg veins) | 0 | 7 | 0 | 10 |

| Median score (% accurate) | 0% | 83% | 0% | 83% |

| Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed ranks test | z = −2.7 (P = 0.01) | z = −3.3 (P < 0.001) | ||

Table 5.

Decisional conflict pre‐ and post‐decision support

| Decision aid alone (n = 10) | Decision aid and counselling (n = 17) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐test | Post‐test | Change | z* | P | Pre‐test | Post‐test | Change | z* | P | |

| A. Scores (median) | ||||||||||

| Total decision conflict | 2.6 | 2.2 | −0.4 | −1.7 | 0.09 | 3.0 | 1.9 | −2.1 | −3.1 | 0.001 |

| Certainty sub‐scale | 3.0 | 2.5 | −0.5 | 3.0 | 2.0 | −1.0 | ||||

| Informed sub‐scale | 3.0 | 2.0 | −1.0 | 3.3 | 1.0 | −2.3 | ||||

| Values clarity sub‐scale | 2.7 | 2.0 | −0.7 | 3.0 | 1.3 | −1.7 | ||||

| Support/pressure sub‐scale | 2.7 | 2.0 | −0.7 | 2.3 | 1.3 | −1.0 | ||||

| Satisfaction sub‐scale | 2.6 | 2.5 | −0.1 | 3.0 | 2.0 | −1.0 | ||||

| B. Frequency agreeing/strongly agreeing with individual items | ||||||||||

| Certainty sub‐scale | ||||||||||

| This decision is easy for me to make | 6 | 11 | ||||||||

| I'm sure what to do in this decision | 7 | 12 | ||||||||

| It's clear what choice is best for me | 6 | 11 | ||||||||

| Informed sub‐scale (median) | ||||||||||

| I'm aware of the choices I have | 9 | 16 | ||||||||

| I feel I know benefits of taking tamoxifen | 5 | 17 | ||||||||

| I feel I know risks of taking tamoxifen | 4 | 17 | ||||||||

| Values clarity sub‐scale (median) | ||||||||||

| I know how important benefits are to me | 6 | 16 | ||||||||

| I know how important risks are to me | 5 | 16 | ||||||||

| I know which is more important to me | 3 | 14 | ||||||||

| Support/pressure sub‐scale (median) | ||||||||||

| I am making this choice without pressure | 16 | 17 | ||||||||

| I have right amount of support from others | 10 | 17 | ||||||||

| I have enough advice about the choices | 2 | 12 | ||||||||

| Satisfaction sub‐scale (median) | ||||||||||

| I feel I have made informed choice | 6 | 13 | ||||||||

| My decisions show what is important to me | 7 | 13 | ||||||||

| I expect to stick with my decision | 3 | 13 | ||||||||

| I am satisfied with my decision | 4 | 14 | ||||||||

*z scores were obtained from Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed ranks test.

The expert panel reviewed the comments of these 10 women and revisions to the decision aid were made. The main revision involved moving one page on the tamoxifen chemoprevention trials to an appendix to decrease the number of pages focused on tamoxifen. Additional outcome measures were added.

Pre‐test–post‐test of the decision aid combined with counselling results

Of the 22 higher risk women invited to participate in this study between December 1999 and April 2000, 20 agreed to participate, 19 completed the pre‐test questionnaire, and 17 completed the post‐test questionnaire. The two women who declined to participate stated that they already had enough information. However, one of these women expressed difficulty making a decision about tamoxifen after her clinic visit and asked for the decision aid. Of the three women who did not complete the study, one was too busy to meet prior to the first visit, one cancelled her clinic visit, and the third had a language barrier.

The demographic characteristics of the women in the decision aid combined with counselling study are presented in Table 2. Their median age was 55 years, the majority were Caucasian, had a post‐secondary education, were married, and had a family history of breast cancer. Their median 5‐year risk of breast cancer was 2.6%. Most women wanted to be involved in the decision‐making.

Following, the use of the decision aid combined with counselling, there was a statistically significant improvement in the total decisional conflict, knowledge, and realistic expectations (P < 0.05). The greatest improvements in decisional conflict occurred on the informed and values clarity subscales and the least improved was observed in the uncertainty sub‐scale (see Table 5). Median knowledge scores increased from 41 to 89% with reductions in the number of incorrect and unsure responses (see Table 3). Realistic expectations of disease outcomes (breast cancer, uterine cancer, and blood clots), improved from a median of 0% before, to 83% after receiving decision support (see Table 4). At baseline, eight women overestimated their risk of breast cancer, six were unsure, and three underestimated their risk.

There was significant reduction in the number of undecided participants from 10 (65%) out of 17 at baseline, to two (12%) out of 17, 2 months after counselling (see Table 6). The main reason given for being unsure at baseline (n = 6) was that women wanted more information. Eleven women who decided not to take tamoxifen immediately after counselling described their decision as influenced by the side‐effects (n = 9) and the concern about taking medications (n = 4). Of the four women who remained unsure immediately after counselling, two were concerned about the side effects and two wanted to wait until after genetic counselling to make their decision. At 2 months post‐counselling, those women who made a decision persisted with that decision. The two women, who decided to take tamoxifen post‐counselling, had started in the chemoprevention trial. Of the four out of 17 women who were unsure immediately after counselling, one decided to participate in the chemoprevention trial, one chose not to take tamoxifen, and two remained unsure with a plan to make their decision after genetic counselling.

Table 6.

Change in predisposition toward tamoxifen 2 months after decision aid and counselling

| 2 months after decision aid and counselling (n = 17) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐test | Yes, take tamoxifen (n = 3) | Unsure (n = 2) | No tamoxifen (n = 12) |

| Yes, take tamoxifen (n = 2) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Unsure (n = 10) | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| No tamoxifen (n = 5) | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| 2 months after decision aid and counselling* (n = 17) | |||

| Pre‐test | Undecided (n = 2) | Decided (n = 15) | |

| Undecided (n = 10) | 1 | 9 | |

| Decided (n = 7) | 1 | 6 | |

*McNemar test binomial distribution (P = 0.02).

The participants’ level of psychological distress from knowing their breast cancer risk decreased after receiving counselling. The median baseline score of 26 (out of a possible high distress score of 60) decreased to 21 at the post‐test (z = −2.4; P = 0.02).

The participants’ intentions to improve healthy life‐style practices significantly improved for exercising (P = 0.03) and eating fruits and vegetables (P = 0.02) but not for alcohol use or healthy body weight. The most common reasons for adopting healthy life‐style practices were to feel better. For three of the 17 women, health problems such as arthritis, back pain, and hypothyroidism interfered with their perceived ability to exercise and/or achieve a healthy body weight. At the 2‐month questionnaire, three of the 17 women were taking action on improving their life‐style by joining a gym, starting to walk, or losing 25 lb.

Both practitioners and participants were satisfied with the effect of the decision aid on preparation for the counselling session. The median score across all items was 4 with a possible range of 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction). The only exception was a median score of 3.5 for the practitioners’ ratings of the effect the decision aid had on the patient–physician relationship. In this study, the α coefficients for internal consistency of the participant and practitioner scales were 0.94 and 0.86, respectively.

Overall, the participants in the decision aid combined with counselling evaluation found the aid to be acceptable in the amount, length, and clarity of information presented. Only one of the 17 participants felt somewhat upset by the information with no stated reason provided; all of her general comments were positive. The majority of women found the decision aid to be balanced and helpful in their decision‐making. All participants recommended the aid for others.

Discussion

The decision aid used alone or combined with counselling decreased some dimensions of decisional conflict, increased knowledge, and created realistic expectations of outcomes. When the aid was combined with counselling, most of the women who were uncertain at baseline shifted away from using tamoxifen at the post‐test. At the same time, there were reductions in women's psychological distress and an increase in their intentions to exercise regularly and eat more fruits and vegetables. Overall, the decision aid was acceptable to women who used it alone or combined with counselling. Both participants and practitioners were satisfied with the effect it had on the consultation visit at the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Clinic.

The results of this study are comparable to other studies with decision aids based on the Ottawa Decision Support Framework. 8 , 25 , 36 , 37 , 38 Following the use of decision aids, participants were more informed, had more realistic expectations of outcomes, decreased levels of decisional conflict, and rated the decision aid as acceptable. A previous study that evaluated the effect of the decision aid on satisfaction with preparation for decision‐making found that decision aids improved participants’ and practitioners’ satisfaction with the decision‐making process. 44

There were several unique contributions of this study. First, a decision aid was developed in an area where no decision aids have been developed. Second, it included and evaluated healthy life‐style practices as options along with medical intervention options, resulting in a shift of intentions to exercise regularly and eat more fruits and vegetables. Third, insights were gained into the practitioner's acceptance of decision aids in clinical practice. Finally, it was the first study to evaluate the effects of decision aids on psychological distress levels. Previous trials have used anxiety scales which have not been sensitive to detecting changes with exposure to decision aids. 7

The decrease in psychological distress measured in this study within a week of post‐decision support is consistent with an earlier study that used the Impact of Event scale at 3 months post‐counselling. 41 In that study, women with a family history of breast cancer who received risk counselling had lower levels of psychological distress compared to women offered usual care. In addition to risk counselling, the women who participated in our decision aid study also received structured information on options to lower their risk of breast cancer. One could hypothesize that the decreased distress following decision support was due to: (a) decreased fear once women's exaggerated or uncertain perceptions of breast cancer risks were realigned; and (b) reassurance that there were actions they could take to try to lower risks. Alternatively, the higher distress at baseline may have been due to the anticipated visit to the clinic that naturally declined once the visit was over. Further evaluation is required to gain a better understanding of the relationship between psychological distress and decision‐making.

There are limitations that restrict the interpretation of the findings and their generalizability. The decision aid was evaluated in a small number of women, the majority of whom were Caucasian and married with post‐secondary education. As well, in the absence of a control group, one cannot attribute all of the observed effects to the decision support intervention. This is particularly relevant to the decision, intention to change life‐style practices, and psychological distress that were only evaluated when the decision aid was combined with counselling. Although participants’ intentions to improve healthy life‐style practices increased, less is known about the impact of their intentions on the implementation of, or adherence to, these changes.

Conclusions

Women at increased risk of breast cancer are likely to experience difficulty in making the decision about tamoxifen as a chemopreventive agent given its potential benefits and harms. The decision aid shows promise as a useful decision support tool in preparing these women for discussion with breast health practitioners. Subsequent research should focus on: a comparison of the effect of the decision aid with counselling to counselling alone; interventions for the implementation and maintenance of healthy life‐style practice; and further evaluation with other groups of women to determine its generalizability. Consideration should be given to developing Web‐based decision aids and a decision support tool for women younger than age 50.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their appreciation to Lisa Johnston, a research coordinator at the Women's Breast Health Centre, who assisted in the recruitment of women to the study and Liz Drake for her assistance in preparing this manuscript.

An advanced practice nurse is a nurse with a graduate education, expanded clinical, theoretical, and research‐based knowledge and skills. 32

References

- 1. Stacey D, DeGrasse C, Johnston L. Addressing the support needs of women at high risk for breast cancer: evidence‐based care by advanced practice nurses. Oncology Nursing Forum, 2002; 29: E77–E84. Retrieved 12 August 2002 from http://www.ons.org/xp6/ONS/Library.xml/ONS_Publications.xml/ONF.xml. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fisher B, Joseph P, Costantino D et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P‐1 study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 1998; 90: 1371–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Powles T, Eeles R, Ashley S et al. Interim analysis of the incidence of breast cancer in the Royal Marsden Hospital tamoxifen randomized chemoprevention trial. Lancet, 1998; 352: 98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Veronesi V, Maisonneuve P, Costa A et al. Prevention of breast cancer with tamoxifen: preliminary findings from the Italian randomised trial among hysterectomised women. Lancet, 1998; 352: 93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chlebowski RT, Collyar DE, Somerfield MR, Pfister DG. American Society of Clinical Oncology technology assessment on breast cancer risk reduction strategies : Tamoxifen and Raloxifene. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 1999; 17: 1939–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Connor AM, Fiset V, DeGrasse C et al. Decision aids for patients considering options affecting cancer outcomes: evidence or efficacy and policy implications. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs, 1999; 25: 67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Connor AM, Stacey, D. Rovner, D et al Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. (Cochrane Review) In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3 Oxford: Update Softwear, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Connor AM, Drake ER, Fiset V, Graham ID, Laupacis A, Tugwell P. The Ottawa patient decision aids. Effective Clinical Practice, 1999; 2: 163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Cancer Institute of Canada . Canadian Cancer Statistics 2002. Toronto: National Cancer Institute , 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Cancer Institute . Probability of breast cancer in American women. In: National Cancer Institute . 7 May 2001http://www.cancer.gov/cancer_information/cancer_type/breast (23 May 2002).

- 11. National Cancer Institute . National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT). In: National Cancer Institute . 4 June 1998. http://207.121.187.155/NCI_CANCER_TRIALS s/PressInfo/PressKit/press/slides/1.html (4 June 1998).

- 12. National Cancer Institute . Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute , 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stacey D, O'Connor A. Cochrane Inventory of Existing Patient Decision Aids . Ottawa Health Research Institute . 30 August 2002. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemilogy/OHDEC/decision_aids.asp (18 October 2002).

- 14. Longnecker MP. Alcoholic beverage consumption in relation to risk of breast cancer: meta‐analysis and review. Cancer Causes and Control, 1994; 5: 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Trentheim‐Dietz A, Newcomb PA, Storer BE et al. Body size and risk of breast cancer. American Journal of Epidemiology, 1997; 145: 1011–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. American Institute for Cancer Research . Food, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: American Institute for Cancer Research , 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Friedenreich CM, Thune I, Brinton LA et al. Epidemiologic issues related to the association between physical activity and breast cancer. Cancer Supplement, 1998; 83: 600–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cline JM, Hughes CL. Phytochemicals for the prevention of breast and endometrial cancer. Cancer Treatment and Research, 1998; 94: 107–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boyd NF, Greenberg C, Lockwood G et al. Effects at two years of a low‐fat, high‐carbohydrate diet on radiologic features of the breast: Results from a randomized trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 1997; 89: 488–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boyd NF, Martin LJ, Noffel M et al. A meta‐analysis of studies of dietary fat and breast cancer risk. British Journal of Cancer, 1993; 68: 627–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holmes MD, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA et al. Association of dietary intake of fat and fatty acids with risk of breast cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1999; 281: 914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Affenito SG, Kerstetter J. Position of the American Dietetic Association and dieticians of Canada: women's health and nutrition. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research, 1999; 60: 85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klijn JG, Janin N, Cortes‐Funes H et al. Should prophylactic surgery be used in women at high risk of breast cancer? European Journal of Cancer, 1997; 33: 2149–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ontario Cancer Genetics Network . Ontario Cancer Genetics Network Consensus Recommendations for Breast Cancer Risk Management in Familial Breast/Ovarian Cancer. Toronto: Ontario Cancer Genetics Network , 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25. O'Connor AM , Tugwell P , Wells GA et al A decision aid for women considering hormone therapy after menopause: decision support framework and evaluation. Patient Education and Counseling, 1998; 33: 267–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision‐making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? Social Science and Medicine, 1997; 44: 681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Entwistle VA, Sheldon TA, Sowden A, Watt IS. Evidence‐Informed patient choice. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 1998; 14: 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hersey J, Matheson J, Lohr K. Consumer Health Informatics and Patient Decision‐making (AHCPR Pub. No. 98‐N001). Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research , 1997.

- 29. Llewellyn‐Thomas H. Presidential Address. Medical Decision Making, 1995; 15: 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mulley A. Outcomes research: implications for policy and practice. In Smith, Delamother T. (eds) Outcomes in Clinical Practice. London: BMJ Publishing Group, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rothert M, Talarcyzk GJ. Patient compliance and the decision making process of clinicians and patients. Journal of Compliance in Health Care, 1987; 2: 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Canadian Nurses Association . Advanced Nursing Practice: A National Framework . Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Nurses Association , 2000.

- 33. Barry MJ, Fowler MJ, Mulley AG, Henderson JV, Wennberg JE. Patient reactions to a program designed to facilitate patient participation in treatment decisions for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Medical Care, 1995; 33: 771–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O'Connor AM. Validation of a Decisional Conflict Scale. Medical Decision Making, 1995; 15: 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Drake E, Engler‐Todd L, O'Connor AM et al. Development and evaluation of a decision aid about prenatal testing for women of advanced maternal age. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 1999; 8: 217–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fiset V, O'Connor AM, Evans WK et al. The development and evaluation of a decision aid for patients with stage IV non‐small cell lung cancer. Health Expectations, 2000; 3: 125–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hing M, Laupacis A, O'Connor AM et al. A patient decision aid regarding antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1999; 282: 737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O'Connor AM, Tugwell P, Wells GA et al. Randomized trial of a portable self‐administered decision aid for postmenopausal women considering long‐term preventive hormone therapy. Medical Decision Making, 1998; 18: 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O'Connor AM, Tugwell P, Wells G. Testing a portable, self‐administered, decision aid for post‐menopausal women considering long‐term hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to prevent osteoporosis and heart disease. Medical Decision Making, 1994; 14: 438 (abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 1979; 41: 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lerman C, Schwartz MD, Miller SM, Daly M, Sands C, Rimer BK. A randomized trial of breast cancer risk counseling: interacting effects of counseling, educational level, and coping style. Health Psychology, 1996; 15: 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. O'Connor AM. Evaluation Measures. In: Ottawa Health Research Institute. 6 September 2001. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemilogy/OHDEC/decision_aids.asp (23 May, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Toronto: Academic Press, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 44. O'Connor AM, Jacobsen M, Elmslie T et al Simple versus complex patient decision aids: is more necessarily better? Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Technology Assessment in Health Care, The Hague, Netherlands, June 2000.