Abstract

Objective To explore women's views on diagnostic breast test information and elicit their preferences for this information.

Design In‐depth, face‐to‐face interview.

Setting and Participants Thirty‐seven women who had previously participated in a population‐based telephone survey.

Main outcome measure Qualitative thematic analysis.

Results Analysis of interview transcripts revealed information about: (1) the wide range of information participants wanted about diagnostic mammography; (2) general reactions to diagnostic breast test information, including positive and negative reactions, views of test accuracy information and perceived influences on information preferences; (3) preferences for information content and presentation including the need for written information, the meaning of statistical information, different views on a simple presentation style, and variation in preferences; and (4) women's understanding of diagnostic test results.

Conclusion Women want a range of information about diagnostic mammography, which is relevant at different times in the decision‐making and testing process. Many women have difficulty interpreting test results.

Keywords: breast cancer, diagnostic tests, information preferences, mammography

Introduction

Information is necessary for patient involvement in decision‐making and informed choice. 1 , 2 , 3 The General Medical Council of the UK and the American College of Physicians recommend that doctors inform patients of the potential benefits and harms of screening tests 4 , 5 and treatment 4 , 6 so that they can make an informed decision about their health‐care. While these recommendations do not explicitly refer to diagnostic tests, it seems reasonable that they should also apply to such tests. In addition to information being necessary for patient involvement in decision‐making, providing pre‐test or pre‐treatment information can help prepare patients 7 and reduce anxiety. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11

Despite the potential benefits of information, and its importance for informed patient decision‐making, two recent reviews of consumer information materials on breast tests concluded that there are major problems with such information. 12 , 13 In particular, they found an emphasis on incidence and relative risk reduction when mortality, absolute risk reduction and number needed to treat are more appropriate; 13 inconsistent information on benefits; 13 inadequate information on potential side‐effects and test accuracy; 12 and a lack of information on the post‐test probability of disease. 12 However, neither review assessed women's information needs with regard to breast tests.

In addition, little is known about women's understanding of diagnostic test results. Such understanding is crucial if women are to use information about the post‐test probability of disease to make decisions about medical tests. A search of the published literature revealed only one study that specifically assessed patient understanding of diagnostic test results. 14 This study used vignettes to assess understanding, none of which included diagnostic tests for breast disease.

These findings are a cause for concern, as a recent population‐based survey by our group found that the majority of women want an equal or more active role in decision‐making about diagnostic and screening tests. 15 Although women in the survey expressed a desire for information about tests including the potential benefits, side‐effects and risks, and test accuracy, this study, being a telephone survey using a standardized questionnaire, could not explore the level of detail women want, their understanding of the information or the best way to present the information.

Thus, we decided to conduct in‐depth, face‐to‐face interviews with a subsample of women from the population‐based telephone survey to (a) explore issues associated with information provision for diagnostic tests; (b) elicit women's preferences for the content and presentation of such information; and (c) assess women's understanding of diagnostic test results. Although the population‐based survey 15 included information needs and preferences in relation to both screening and diagnostic tests, we decided to focus the interviews on diagnostic breast tests, as little work has been carried out on women's information needs for, and understanding of, diagnostic breast tests.

Methods

Participants

The sample was taken from women aged 30–69 years, who had previously participated in the population survey telephone described above. A description of the survey sample is provided elsewhere. 15 Participants included women who had previously undergone breast tests and women who had not.

Procedure

At the conclusion of the survey, 15 interviewers asked if the woman would be willing to receive a mailed invitation to an in‐depth, face‐to‐face interview to find out her views on the best way of presenting information about diagnostic breast tests. Two hundred and eleven women (of the 652 surveyed) agreed to this. Women were randomly selected from this list to receive a letter inviting them to attend an interview at The University of Sydney. No inducement was offered but a small fee was paid to cover parking and/or travel costs. Letters were despatched in batches of 20, and recruitment stopped when information redundancy was obtained.

Interview development

The researchers developed the initial interview script using the available literature and results from our population‐based survey. 15 Researchers with experience in interview design and qualitative research methodology, who were not involved in the study, reviewed the interview script. The script was then pilot tested with six women who had previously participated in the survey. Following this, the number of categories of mammography results was changed from five (normal, benign, indeterminate, suspicious, malignant) to three (normal, inconclusive and abnormal). Normal and benign were combined to normal; indeterminate was renamed inconclusive; and suspicious and malignant were combined for abnormal. A breast clinician, experienced in the diagnosis of breast disease, approved these combinations and terminology as those commonly used in Australia to report the results of diagnostic breast tests. In addition, a minor adjustment was made to the question on understanding of test accuracy, with women asked to interpret two test results instead of three.

The final interview script contained semi‐structured questions that elicited information on desire for pre‐decision information about diagnostic mammography; preferences for the content, presentation and timing of information about mammography; understanding of test results; and demographic characteristics. Information was presented on coloured A4‐sized cards.

Pre‐decision information

Women were asked, hypothetically, what information they would like about diagnostic mammography before making a decision about whether or not to have it. They were specifically asked about practical issues, the doctor's assessment, side‐effects, risks and accuracy of the test, if they did not identify these issues without prompting.

Preferences for information about the accuracy of diagnostic mammography

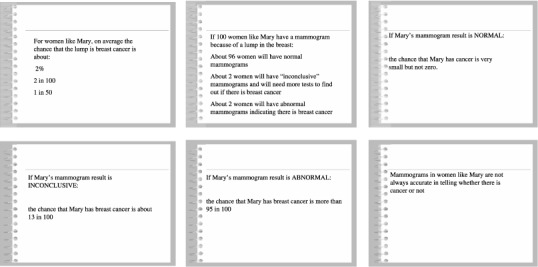

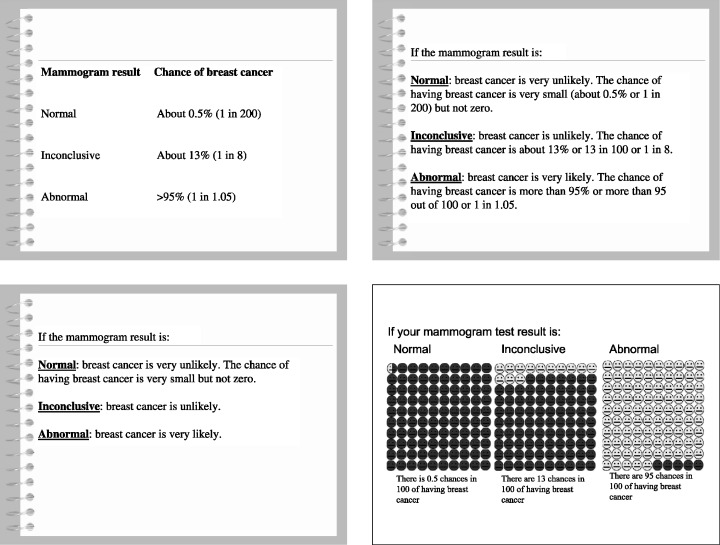

Women were asked to consider the hypothetical case of Mary, a 50‐year‐old women who had discovered a lump in her breast for the first time. They were shown six pieces of information about diagnostic mammograms (pre‐test probability of disease, probability of a normal, inconclusive and abnormal result; post‐test probability of disease (three cards) and test accuracy, (Fig. 1) and were asked (as Mary) which pieces of information they wanted, to rank them in the order of most to least preferred, and to indicate whether they would want the information before deciding to have a mammogram or when receiving their results. Reasons for their responses were explored. Post‐test probabilities were calculated using a pre‐test probability of 2%, which was derived from statistics from a diagnostic breast clinic in Sydney, Australia and published likelihood ratios calculated from Australian data. 16 To elicit preferences for the presentation of information, women were shown the same information presented in four different ways: numerical probability; qualitative probability labels; combined numerical and qualitative probability; and 100 faces (Fig. 2). They were asked to rank these in order of preference and to give their reasons for this order.

Figure 1.

Interview cards showing information about mammography.

Figure 2.

Interview cards showing four different ways of presenting the same information.

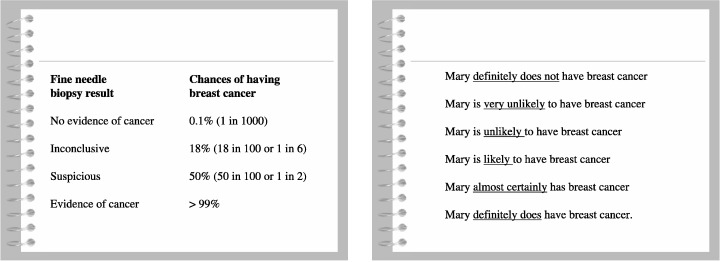

Understanding of test results

To assess women's understanding of test results, the scenario was further developed so that Mary underwent breast biopsy. Women were shown a card stating the probability of cancer with different fine needle biopsy results and asked to say how likely cancer was if a biopsy result of no evidence of cancer and an inconclusive result was received (Fig. 3). We considered very unlikely to be the correct interpretation of no evidence of cancer and either unlikely or likely to be correct interpretations of an inconclusive result.

Figure 3.

Interview cards showing the post‐test probability of cancer for breast biopsy and qualitative labels.

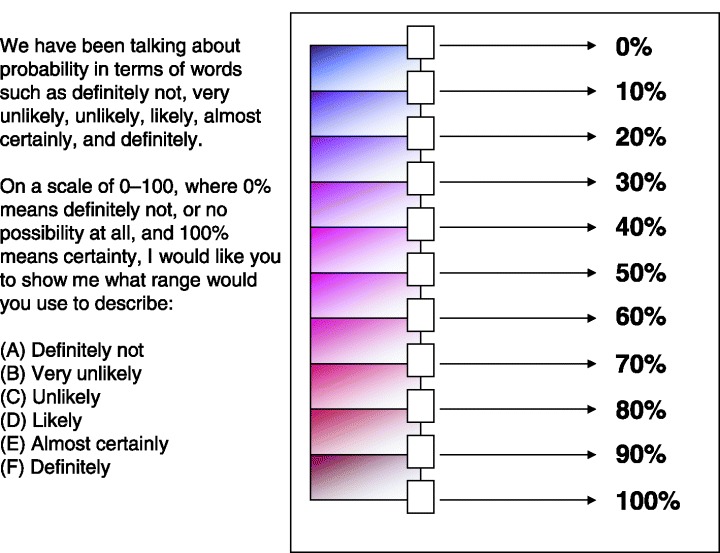

Given that the literature has consistently shown considerable variation in the way people interpret qualitative labels, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 the women were asked to assign numerical values to each of the qualitative labels. We took this into account when assessing whether women truly understood a no evidence of cancer and an inconclusive result. To do this, we checked whether the numerical values of the qualitative labels chosen for the no evidence of cancer result, and the inconclusive result included the actual probability of cancer for that result. For example, suppose we want to assess a participant's understanding of the chance of having breast cancer with a no evidence of cancer result (Fig. 3). Our participant interprets this to mean that Mary is unlikely to have breast cancer using the qualitative labels (Fig. 3). Using the analogue scale, she further tells us that an event is unlikely if there is a 10–20% chance that it will happen (Fig. 4). The actual probability of cancer with a no evidence of cancer result is 0.1% (clearly shown in Fig. 3). As this lies outside the range of values for the qualitative label our participant selected, we interpret this to mean that she does not fully understand the test result.

Figure 4.

Visual analogue scale used to elicit values for each qualitative label.

Demographic characteristics

Women were asked their age, country of birth, highest level of education and the sources of health information they generally used. They were specifically asked whether they obtained health information from a doctor, the media, the Internet and books, if they did not mention these sources without prompting.

Analysis

Frequency counts were used to analyse the demographic data. Analysis was performed using SPSS version 10.0 for Windows. 23 Data on region was compiled using the postcode to which the invitation was sent. One of the authors (HD), with experience in content analysis, analysed all of the transcripts using the constant comparative method. 24 This method involves identifying participant responses and comparing and contrasting them to identify recurring ideas and themes. Another author (PB) reviewed the analysis. These authors then met to discuss the analysis, with any differences resolved by discussion. Representative quotes, that illustrate the identified issues, were selected.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Thirty‐seven women completed an interview. A summary of the demographic characteristics of the participants is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the interview participants

| Characteristic | Interview participants n = 37 (%) | General population women (age 30‐69 years, %)1,2 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 30‐39 | 6 (16) | 33 |

| 40‐49 | 6 (16) | 30 |

| 50‐59 | 16 (43) | 21 |

| 60‐69 | 9 (24) | 17 |

| Education | ||

| School only | 9 (24) | 59 |

| Post school | 28 (76) | 42 |

| Region | ||

| Metropolitan | 36 (97) | 66 |

| Rural | 1 (3) | 34 |

| Country of birth | ||

| Australia | 28 (76) | 69 |

| Other | 9 (24) | 31 |

1According to Australian Bureau of Statistics census data. 25

2Totals may not add to 100 because of rounding.

Content analysis of the transcripts

Analysis of the interview transcripts revealed a wide range of pre‐decision information women wanted about diagnostic mammography; positive and negative reactions to the provision of information; preferences for the content and presentation of information; and participants’ understanding of breast biopsy results. There appeared to be no major differences in the perceptions and preferences of women aged 50 years and older and women younger than 50 years, or between women who had undergone breast tests and those who had not.

1) Types of information wanted

Women nominated a wide range of information they would like to receive before deciding to have a diagnostic mammogram. Table 2 shows the eight categories of information women wanted, the details they wanted within each category and whether these details were prompted or unprompted.

Table 2.

Types of information wanted before deciding to have a diagnostic mammogram

| Information | Numbers of times mentioned | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unprompted | Prompted | Total | |

| Doctor's opinion about the lump | |||

| What is the lump? | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Is a mammogram necessary? Why? | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| What is the possible cause of the lump? | 2 | ‐ | 2 |

| Potential benefits | |||

| What benefit will a mammogram be? | 3 | ‐ | 3 |

| Potential risks | |||

| What are the dangers of having a mammogram? | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Will I be exposed to radiation? | 4 | ‐ | 4 |

| Will the mammogram affect the lump? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| If it's a cyst, will it burst? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Possible side‐effects | |||

| Will the mammogram hurt? | 9 | 10 | 19 |

| What is the chance of each side‐effect? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Will I feel discomfort? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Accuracy | |||

| How accurate is a mammogram? | 7 | 13 | 20 |

| What is the chance it will miss a cancer? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Will the results be definitive enough for action to be taken? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Alternative tests | |||

| What other tests can I have? | 4 | ‐ | 4 |

| Could I have an ultrasound first? | 2 | ‐ | 2 |

| Will I need to have other tests after? | 2 | ‐ | 2 |

| Is a biopsy better than a mammogram | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Should I have a biopsy at the same time? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Is this the best test to have? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Practical issues | |||

| How is a mammogram actually done? | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| How long will it take? | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Where do I go to have it? | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| What do I need to take with me? | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Who conducts the test? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| What shouldn't I wear? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Can I wear talcum powder/deodorant? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Will I need to fast? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| How soon can I have it done? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| What different machines can be used? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Possible outcomes | |||

| What are the possible outcomes? | 5 | ‐ | 5 |

| What is the worst possible outcome? | 2 | ‐ | 2 |

| What will happen if I don't have it? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| What happens if it's cancer? | |||

| What are the treatment options? | 4 | ‐ | 4 |

| Would chemotherapy be required? | 2 | ‐ | 2 |

| What would the prognosis be? | 2 | ‐ | 2 |

| What is the treatment success rate? | 2 | ‐ | 2 |

| How far has the cancer spread? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Will I be able to keep working? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| How long will I need to convalesce? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Would there be support (e.g. home help) available? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Results | |||

| How long will it take to get the result? | 3 | ‐ | 3 |

| How do they determine if anything is wrong? | 2 | ‐ | 2 |

| Who examines the mammogram? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| How do I find out if anything is wrong? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| What happens once the result is known? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Cost | |||

| Is there a Medicare rebate? | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

2) General reactions to information about diagnostic mammography

Analysis of the transcripts revealed four main themes; (a) positive and (b) negative responses to information provision; (c) views on information about the accuracy of diagnostic mammography; and (d) influences on information preferences.

(a) Positive responses

Information as a coping mechanism

Information provided before a mammogram, was seen as a coping mechanism by some women. For them, this information provided reassurance and hope. In addition, it prepared them for having the test, for the potential results and the implications of those results by facilitating their understanding of the situation. For these women, the provision of pre‐decision information was necessary, if they were going to make a good decision. One woman said:

To see how you stand, what you're in for, what the prospect is, otherwise you're going in with your eyes closed.

Another said:

I guess to put it into another perspective that even if you have a lump you don't have to panic to the point of falling to pieces.

Some women felt there was no decision to make about having a mammogram; if they had a breast lump they would certainly have a mammogram.

One woman commented that the information on post‐test probability gave her the courage to have the mammogram. She said:

Yes I do [want information that says the chance of cancer is 13 out of 100] because it's not such a high number.

(b) Negative responses

Jumping the gun

Other women felt that pre‐decision or pre‐test information on the meaning of test results was jumping the gun. Reasons for this view included the belief that such information would increase the anxiety and fear a woman would feel having found a lump in her breast; the perceived lack of relevance of information on the post‐test probability of disease at that time; and a concern that the information could falsely reassure women. They felt the potential consequence of this was a woman refusing a test because she did not perceive the risk as serious. For these women, providing information about the probability of cancer with different test results would be more useful when they received the result of their mammogram. Two women commented:

I think [having that information] terrifies you more. It worries you more.

The [information about the chance of cancer with different test results] only makes people worry unnecessarily, which I think is defeating and I think will bring people's health down and they're going to start worrying … so therefore it's unnecessary to make them worry to start with.

c) Test accuracy: how much detail?

Almost all of the women interviewed said they felt anxious upon hearing that mammograms are not 100% accurate. However, this anxiety was more evident in those women who had always assumed that mammograms provide a definitive answer. These women did not want to know mammograms are not 100% accurate as they felt it would cause them to worry that they may have breast cancer after receiving a normal result. They expressed a need for certainty in the diagnosis of their breast symptom and wanted to know if there was an alternative test, which would be more accurate.

Most of the women interviewed felt that it was important for women to know that mammograms are not 100% accurate, as it avoids false reassurance. However, they differed on just how much detail should be provided, with some women wanting statistical information on the accuracy of diagnostic mammography and others wanting only to know that diagnostic mammography is not 100% accurate. One woman felt that the lack of 100% accuracy was positive, as it provided hope that an inconclusive or abnormal result was incorrect.

(d) Influences on information preferences

Use of information depends on the perceived severity of test side‐effects and potential outcomes.

When asked if and when they would use information about a test to assist decision‐making, most women said that they would use information when there was a strong possibility that the test would have a side‐effect. They considered these tests to be high‐risk and wanted more information about them. One woman said:

If high risk [I] want information, if not high risk, there's no need [for information].

They would also use information when making a decision about a test where the potential outcome was perceived as serious (e.g. a cancer diagnosis). One woman said:

I think it's more important for breast cancer because it's cancer, cancer being a deadly word. Like with cholesterol, cholesterol doesn't bring up the emotions that cancer does, so people worry more [about cancer and] they need more information.

Desire for information affected by the probability of cancer

Women expressed a greater desire for information that was positive. In particular, a number of women said they would not want to know, prior to the mammogram, that the chance of having breast cancer with an abnormal result was more than 95% (Fig. 2). They felt the information was too negative and would frighten them. One woman commented:

Well I think if I was told that I had a 95 out of a 100 chance that the lump in my breast was cancer, I don't think I'd want to know.

3) Preferences for information content and presentation

Need for written information

Written information was perceived as a useful resource, given women are likely to be upset, and therefore unable to take in any or all of the information their doctor tells them. In addition, many women felt written information would be useful in assisting them to explain the situation and mammography to their partners, family and friends. One woman said:

I would like something in writing because the thing is often [when] I'm particularly upset or thrown, I don't think clearly and I don't understand and I'll say ‘yes’ but I don't understand and I want to take away a sheet of paper which is clear or something that, you know, that I can read at home in peace and quiet or can give my sister to read.

Relevance of statistics for an individual

For a small number of women statistical information about the probability of a lump being cancer and the probability of cancer with different test results was irrelevant. They were only interested in whether or not they had breast cancer; they were not interested in statistics about a group of women that did not include them. One woman said:

I don't want to know about all the other people. It's my body, my cancer, my breast, I want to know just for me.

Type and detail of information varied between women and according to time

While there was considerable variation between women in their preference for type and detail of information, three main groups were evident. One group of women wanted only basic information, citing a lack of interest in the actual percentage of people to whom a certain statistic applied. They were more interested that an event, for example, test inaccuracy, was possible. A second group of women wanted very specific information, citing the reassuring nature of knowing exactly what was going on. These women said that they would filter out any information they did not like or considered relevant.

The third group of women wanted basic information to begin with, then more detailed information at a later time. In particular, these women were happy to know before making a decision or undergoing a test, that mammograms are not 100% accurate and to wait to know the actual post‐test probability of disease until they received their result.

Present the information simply to facilitate understanding

All of the women interviewed felt that information should be presented as simply as possible, as women consulting about a breast lump are anxious and already overloaded with information. However, what constituted a simple presentation differed among participants. Most women agreed that the use of mathematical symbols such as ‘<’ (less than) and ‘>’ (greater than) should be avoided and that numbers and percentages should be put in context by attaching to them a qualitative label, such as likely.

Women were divided in their views on whether written presentations such as plain text or pictorial presentations such as faces were easier to understand. Some women felt that percentages were difficult to understand on their own. These women preferred percentages in the context of a qualitative label or information presented in a visual format (100 faces). They felt the latter made the information easier to understand, particularly for women with poor literacy skills.

Preference for written or pictorial presentation of information

Women were divided in their preference for information presented as 100 faces, with the applicable number coloured in (Fig. 2). Some women felt that the faces made the information clear and easy to understand. Those women who disliked the faces, tended to do so because of their emotional impact. They felt presenting the information as faces made it confronting and too sharp. One woman commented:

The little faces, [you] see all these chances, its scarier, each chance looks like a human being.

4) Women's understanding of test results

Table 3 shows the number of women who correctly interpreted two test results. Of particular concern were the five women who thought that no evidence of cancer meant that the woman definitely did not have cancer.

Table 3.

Women's understanding of two breast biopsy results

| Result | Number of women who answered correctly (n = 37) | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | Taking descriptor values into account | |

| No evidence of cancer | 20 | 6 |

| Inconclusive | 27 | 7 |

There was considerable variation in the numerical values women assigned to the qualitative labels. Table 4 shows the value range assigned to each descriptor. When we took the variation in numerical values into account, six women correctly interpreted the no evidence of cancer result and seven women correctly interpreted the inconclusive result (Table 3).

Table 4.

Range of values (%) assigned to each qualitative label

| Qualitative label | Lower value | Upper value |

|---|---|---|

| Definitely not | 0 | 10 |

| Very unlikely | 0 | 30 |

| Unlikely | 0 | 90 |

| Likely | 15 | 100 |

| Almost certainly | 35 | 100 |

| Definitely | 50 | 100 |

Discussion

General reactions to information about diagnostic mammography

Guidelines recommend the provision of information for informed decision‐making about screening 4 , 5 and treatment 4 , 6 and it appears reasonable that the same information should be provided for diagnostic tests. A previous population‐based survey 15 by this group shows that almost all women want information on the potential for a false test result and test side‐effects, even when they predict this information would make them anxious. The current study provides more detail about the type of information wanted on false results and side‐effects and looks, in particular, at information required about the post‐test probability of disease. It was necessary to ask women in more detail about the information they wanted before deciding about having a diagnostic mammogram, as previous research has shown that patients do not attach equal importance to all pieces of information within a category. 26 , Table 2 clearly shows that some pieces of information were mentioned more than others, indicating that more women considered them important for making their decision about diagnostic mammography. Some women who previously had screening mammograms had to be prompted more than other women about what information they would want before deciding about having a diagnostic mammogram. This was particularly true for practical issues, such as what actually happens when one has a mammogram and how long it takes, on which these women were already knowledgeable.

Of particular interest in this study is the finding that many women do not want information on the post‐test probability of breast cancer when deciding whether they want to have a mammogram to investigate a breast lump. They would prefer to have this information when receiving their mammogram result and would use it to interpret that result. There appears to be, therefore, differences in the way medical professionals and lay people make decisions about medical tests. Doctors use information about test characteristics, such as likelihood ratios to estimate the post‐test probability of disease, to assess whether there is any value in referring a patient for a diagnostic test, given their pre‐test probability of disease. The fact that most women in this study did not want this information until they received their results suggests our participants would use this information to assist them to understand the test results. This difference between doctors and participants in this study highlights the need, when providing information, to consider the purpose for which people, in practice, would use the information. It raises two important issues. First, the extent to which patients can or want to be, in practice, involved in decisions about having a diagnostic test, given they may not want relevant information before making a decision. Second, the relationship between diagnostic test, screening test and treatment decisions. Are diagnostic tests so different from screening tests and treatment that the same issues about informed decision‐making and recommendations regarding what information should be provided to patients, do not apply?

It may be that, as in this study, people do not perceive there is a decision to make when they have a symptom, as testing is considered the only option. However with screening and treatment people perceive there are at least two options (to have or not have screening/treatment), and therefore a decision to make. However, this argument ignores the fact that the majority of women want an equal or more active role in test decision‐making. 15 Therefore, if they want to be involved in decision‐making, they should be provided with the relevant information, otherwise they are unable to make an informed decision. This raises questions about how to ensure patients obtain the necessary information to enable them make an informed decision while accommodating information preferences. While this issue has been raised in the context of diagnostic breast tests in this study, it may not be confined to such tests.

The lack of relevance of statistical information for some women poses a problem for their involvement in decision‐making. Health‐related decisions are commonly based on statistical information with average values. For example, the national breast screening program in Australia uses statistics to provide reasons why women aged 50–69 years should attend for a screening mammogram every 2 years. 27 If women do not consider statistical information relevant because it is group data that may not represent them as an individual, on what basis can they make an informed decision?

This is the first known study to assess women's understanding of breast biopsy results. A substantial proportion of women were unable to correctly interpret a no evidence of cancer and an inconclusive result. Some women found the lack of a neutral category between likely and unlikely difficult, but as the probabilities they were being asked to interpret were 0.1% and 18%, their difficulty suggests that women may not understand the results. Consistent with the literature, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 there was considerable variation in the numerical values women assigned to each of the qualitative labels. When these differences were taken into account, few women correctly interpreted the test results. Most women's inability to correctly interpret a diagnostic test result using qualitative labels suggests such descriptors, often used to describe probability in health‐care, may be inappropriate for health‐care consumers.

Limitations

This was a qualitative study involving a subsample of women who had completed a population‐based telephone survey on women's preferences for and experiences in decision‐making for tests and treatment and their need for information. Compared with the general population, interview participants were more likely to be older, live in a metropolitan area and have post‐school qualifications. Our sample includes women most and least likely to want to participate in health‐care decisions and to want information. 15 This study cannot provide any information about the extent to which the preferences for information content and presentation found in this study represent those of other women in the community. Thus it would be pertinent to assess the prevalence of the preferences found in this study in a larger representative sample of women.

This study elicited preferences for different presentation formats. An assessment of the understanding of information using different presentation formats was outside the scope of this study. However, given that the most preferred format may not be the best understood format, there is a need to assess women's understanding of information using the formats they selected as most preferred in this study.

Conclusion

This study builds on previous research with a representative sample of women, 15 which found women want information on test accuracy and test side‐effects, by providing a valuable insight into women's preferences for the content and presentation of information materials for, and their understanding of, diagnostic breast test results. In addition, it raises several important issues that have the potential to impact on the provision of information to consumers and their involvement in health‐care decisions: (1) differences in the way health‐care professionals and consumers use information on the post‐test probability of disease and related questions about consumers’ ability to participate in diagnostic test decision‐making; (2) the reconciliation of the provision of information necessary for informed decision‐making with consumer preferences; and (3) potential differences in the way diagnostic tests, screening tests and treatment are viewed by consumers.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia.

References

- 1. Ward J. Population‐based mammographic screening: Does ‘informed choice’ require any less than full disclosure to individuals of benefits, harms, limitations and consequences? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 1999; 23: 301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coulter A, Entwistle V, Gilbert D. Sharing decisions with patients: is the information good enough? British Medical Journal, 1999; 318: 318–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fallowfield, L. Participation of patients in decisions about treatment for cancer: Desire for information is not the same as a desire to participate in decision making. British Medical Journal, 2001; 323: 1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. General Medical Council . Seeking Patients’ Consent: the Ethical Considerations. London: General Medical Council, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5. American College of Physicians . Clinical Guideline part III: screening for prostate cancer. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1997; 126: 480–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American College of Physicians . Guidelines for counselling postmenopausal women about preventive hormone therapy. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1992; 117: 1038–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schofield MJ, Sanson‐Fisher R. How to prepare cancer patients for potentially threatening medical procedures: consensus guidelines. Journal of Cancer Education, 1996; 11: 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. D'haese S, Vinh‐Hung V, Bijdekerke P et al. The effect of timing of the provision of information on anxiety and satisfaction of cancer patients receiving radiotherapy. Journal of Cancer Education, 2000; 15: 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Humphris GM, Ireland RS, Field EA. Randomised trial of the psychological effect of information about oral cancer in primary care settings. Oral Oncology, 2001; 37: 548–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mainiero MB, Schepps B, Clements NC, Bird CE. Mammography‐related anxiety: effect of preprocedural patient education. Womens Health Issues, 2001; 11: 110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poroch D. The effect of preparatory patient education on the anxiety and satisfaction of cancer patients receiving radiation therapy. Cancer Nursing, 1995; 18: 206–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Croft E, Barratt A, Butow P. Information about tests for breast cancer: what are we telling people? Journal of Family Practice, 2002; 51: 858–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Slaytor EK, Ward JE. How risks of breast cancer and benefits of screening are communicated to women: analysis of 58 pamphlets. British Medical Journal, 1998; 317: 263–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamm RM, Smith SL. The accuracy of patients’ judgments of disease probability and test sensitivity and specificity. Journal of Family Practice, 1998; 47: 44–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davey HM, Barratt AL, Davey E et al. Medical tests: women's reported and preferred decision making roles and preferences for information on benefits, side effects and false results. Health Expectations, 2002; 5: 330–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Houssami N, Irwig L. Likelihood ratios for clinical examination, mammography, ultrasound and fine needle biopsy in women with breast problems. The Breast, 1998; 7: 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bryant GD, Norman GR. Expressions of probability: words and numbers. New England Journal of Medicine, 1980; 302: 411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kong A, Barnett GO, Mosteller F, Youtz C. How medical professionals evaluate expressions of probability. New England Journal of Medicine, 1986; 315: 740–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mazur DJ, Hickam DH. Patients’ interpretations of probability terms. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1991; 6: 237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakao MA, Axelrod S. Numbers are better than words. Verbal specifications of frequency have no place in medicine. American Journal of Medicine, 1983; 74: 1061–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Robertson WO. Quantifying the meanings of words. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1983; 249: 2631–2632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Woloshin KK, Ruffin MT, IV, Gorenflo DW. Patients’ interpretation of qualitative probability statements. Archives of Family Medicine, 1994; 3: 961–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. SPSS Inc. SPSS Version 10.0.5 for Windows. Chicago: SPSS Inc., 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Glaser BG, Strauss Al. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine Publishing Company: New York, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Australian Bureau of Statistics . Data provided on request.

- 26. Feldman‐Stewart D, Brundage MD, McConnell BA, MacKillop WJ. Practical issues in assisting shared decision‐making. Health Expectations, 2000; 3: 46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Why Should I Have A Mammogram? Available at: http://www.breastscreen.info.au/why/index.htm (Accessed 20 June 2002).