Abstract

Context Medical issues are widely reported in the mass media. These reports influence the general public, policy makers and health‐care professionals. This information should be valid, but is often criticized for being speculative, inaccurate and misleading. An understanding of the obstacles medical reporters meet in their work can guide strategies for improving the informative value of medical journalism.

Objective To investigate constraints on improving the informative value of medical reports in the mass media and elucidate possible strategies for addressing these.

Design We reviewed the literature and organized focus groups, a survey of medical journalists in 37 countries, and semi‐structured telephone interviews.

Results We identified nine barriers to improving the informative value of medical journalism: lack of time, space and knowledge; competition for space and audience; difficulties with terminology; problems finding and using sources; problems with editors and commercialism. Lack of time, space and knowledge were the most common obstacles. The importance of different obstacles varied with the type of media and experience. Many health reporters feel that it is difficult to find independent experts willing to assist journalists, and also think that editors need more education in critical appraisal of medical news. Almost all of the respondents agreed that the informative value of their reporting is important. Nearly everyone wanted access to short, reliable and up‐to‐date background information on various topics available on the Internet. A majority (79%) was interested in participating in a trial to evaluate strategies to overcome identified constraints.

Conclusion Medical journalists agree that the validity of medical reporting in the mass media is important. A majority acknowledge many constraints. Mutual efforts of health‐care professionals and journalists employing a variety of strategies will be needed to address these constraints.

Keywords: medical journalism, evidence‐based medicine

Background

Extensive interest in reports on health and medicine in the mass media and wide coverage raises concerns for many health professionals as well as medical reporters. 1 Journalists working in the medical field are often accused of being sensational, speculative or of paying too much attention to anecdotal findings. 2 , 3 , 4 Reporters, on the other hand, find scientists unable to describe their research in understandable terms, or interested in using mass media to promote their own interests. Contact between journalists and physicians is often a meeting between two cultures with rather little in common and with many possibilities for misunderstanding. 5 , 6 Despite this, very little attention has been paid to the working processes of journalists covering medicine (used broadly here and in the rest of this paper to include coverage of health and health‐care) and how these processes affect what is reported.

The mass media are an important source of medical information. Medical reports can increase or diminish the willingness of individuals to seek medical care (or participate in clinical trials), may raise expectations (sometimes falsely), may dash hopes, or may provoke alarm (sometimes unnecessarily). Press coverage of dramatic medical stories, such as organ transplants, often raise unrealistic expectations and may promote new technologies that have not been adequately evaluated. Although the impact of health‐care reporting is difficult to measure 7 , 8 the mass media can influence individual health behaviour, health‐care utilization, health‐care practices, health policy and the stock market. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 In many countries new legislation on patient's rights includes the right to make informed decisions about one's own health‐care. The ability to exercise this right effectively depends on exposure to good information. Policy makers and physicians also get medical information from the mass media and this can affect their work both directly and indirectly. 8 , 14 , 15 This information should be valid.

Journalists struggle to provide accurate and relevant information about health and medicine, but there are many obstacles between a research report and a short, easy‐to‐understand and entertaining article. 7 The aim of this study was to identify and elucidate obstacles that hinder journalists from improving the informative value 16 (Box 1) of their work and possible strategies for overcoming these obstacles.

Table Box 1 .

Definition of ‘informative value’

| The following definition was used in this study, in both the telephone interviews and the survey: |

| By ‘informative value’ we mean the extent to which health‐care reports provide valid and useful information. ‘Informative value’ also signifies that the basis or evidence for what is reported is apparent. A report with high ‘informative value’ allows the audience to draw conclusions about: |

| • the applicability of the information to personal or policy decisions |

| • the strength of the evidence upon which the report is based (or the degree of uncertainty) |

| • the size of the effects, risks, associations, or costs that are reported |

We found few articles and very few empirical studies on barriers to improving the quality of medical reporting or interventions to improve the informative value of medical reporting. Several authors have discussed problems with the dissemination of health information to the general public through the mass media and recommend better education for journalists. 1 , 2 Lack of training in critical appraisal and translation of scientific jargon have been reported as factors that limit the scientific quality of medical reporting. Demands from editors for sensational stories have also been identified as a problem in the literature. 17 Other constraints that have been identified in the literature include: lack of time and space, competition among journalists and problems finding reliable information. 18 The structure of news stories, the need for something newsworthy, and problems negotiating with editors and headline writers have also been identified as barriers. 7

Methods

Focus groups

In June 1999 we organized two focus groups with a total of 20 participants in two different countries. In Sweden journalists were identified by personal contacts and senior British Medical Journal (BMJ) staff assembled a group in the UK. Journalists in both groups were chosen to represent different media and different levels of education and experience. Inclusion criteria were that participants were full‐time health or medical reporters, either employed or freelancers, who had been working with health issues for at least 3 years. The focus groups were open forums with possibilities for free exchange of views on working situations. We had previously constructed lists of possible barriers and strategies for addressing them, based on our review of the literature and personal experience. Each possible barrier was presented orally and thoroughly discussed, with possible solutions for different types of media. These lists were expanded and modified based on the focus group discussions. These group discussions were tape recorded, transcribed and reviewed by two of us (AL and CC).

Survey

The data produced by the focus groups and background literature search were used to design a survey instrument (available from the authors) comprising 28 closed questions, including some four‐point Likkert scales, with a possibility for writing in comments for all questions. The survey was put up on a website. Journalists with an e‐mail address as shown on the membership lists of associations for science and medical journalists (687 people in 37 countries) were invited to respond to the survey or to contact us if they preferred receiving a paper copy of the survey. The target group for this study was professional journalists specializing in health and science reporting. To be included in the study a journalist had to produce at least 10 stories on health or medicine per year. A hard copy of the survey was mailed to a sample of the first 100 people on the lists without e‐mail addresses.

For each respondent, we assigned a ‘dominant media’, according to the media for which that respondent claimed to use the highest percentage of her time. Respondents with no dominant media (i.e. with a tie between two or more different types of media) were assigned dominant media ‘None’. Responses on the four‐point Likkert scales to statements about each barrier were categorized as ‘Yes’ if the respondent either agreed or strongly agreed that the barrier existed. All survey responses were summarized, with frequencies tabulated for dichotomous responses and means, standard deviations, and ranges for continuous responses.

Telephone interviews

To elucidate or explain responses in the survey, we then conducted semi‐structured, in‐depth interviews by telephone with 10 health reporters from Europe, Canada and Australia. The subjects were chosen through our network of contacts, with the aim to reach people from different countries and with different levels of education and experience. The goal of the telephone interviews was to elicit a broad and in‐depth picture of the interviewees’ working situation in their own words by probing deeply into their experiences. The interviewers followed an interview guide including questions to elicit background information, experienced constraints and strategies that might overcome them, factors that they found enabling, and their definition of scientific quality in health reporting. A preliminary review conducted when 10 interviews had been completed suggested that data saturation was reached. The interviews were recorded on mini‐disc and transcripts were reviewed by two of us (AL and CC).

Results

Focus groups

The participants in the focus groups were invited to speak freely of their experiences and to exchange views on problems in daily work. The British group pointed out competition and commercialism as major obstacles: ‘Someone said that a journalist's job is to explain the world. That's the kind way of putting it. The unkind way is to say that a journalist's job is to sell newspapers. This is a commercial business, you know. If we don't sell newspapers we are out of our job.’ Public relation agents and lobby groups that want to promote certain ideas, studies or a special issue were also seen as obstacles.

Possibly due to their being highly experienced, most of the reporters in the UK group did not identify lack of time or knowledge as major concerns. ‘A professional reporter learns to work very fast.’

Journalists writing for magazines claimed that there were problems with editors and the structure of the media. ‘Editors are not interested in what is accurate and what isn't accurate. As long as it doesn't kill anybody, they're not bothered if it's not actually spot on.’

The Swedish group indicated greater concern about the lack of time and problems finding reliable sources. ‘It can be that something arrives on my desk in the morning and I need to have a story ready in the afternoon and in addition I will be interrupted by all sorts of other things.’

Some of the Swedish people were concerned about how to choose the right subject in the enormous flow of information from different sources. The selection process was thought to be difficult, given the demand for something newsworthy, not too complicated and relevant to a big audience. ‘People don't read newspapers sitting in armchairs in front of a fire. They read them on station platforms, crowded subways, stuck on the street, etcetera. So the stories have got to grab them by the throat.’

Survey

The 148 journalists that answered the survey were quite experienced (Table 1). Most of them worked in magazines or newspapers and the average journalist had been working almost 10 years with health matters. Twenty‐one reporters had worked for more than 20 years with health stories.

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey respondents

| Number | Stories/year* | Proportion on health (%)* | Years* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magazine | 39 | 30 | 80 | 9 |

| Newspaper | 37 | 60 | 90 | 7 |

| Television | 17 | 40 | 70 | 7 |

| Internet | 12 | 50 | 100 | 9 |

| Radio | 11 | 50 | 40 | 6 |

| Books | 4 | 12 | 90 | 16 |

| Other | 16 | 18 | 90 | 6 |

| None (tied)† | 12 | 40 | 55 | 12 |

| Total | 148 | 35 | 80 | 8 |

*Median number of stories prepared per year; proportion of those stories that were on medicine, health or health‐care; and number of years working as a medical journalist.

†Journalists who worked an equal proportion of time in two or more media.

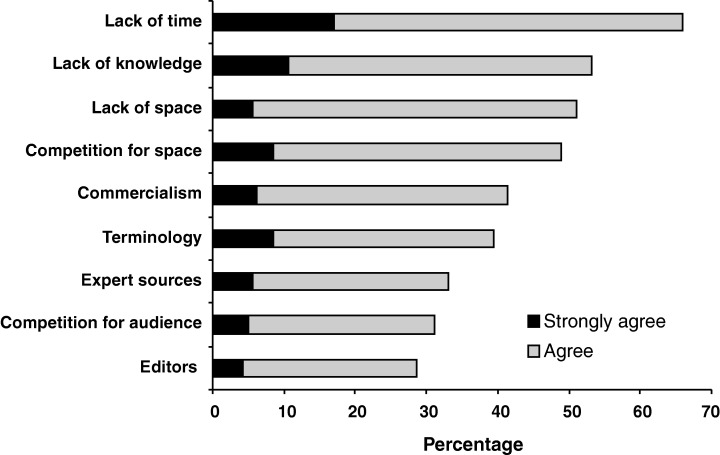

We identified nine barriers to improving the informative value of medical reporting (Fig. 1). The predominant ones were lack of time, space and knowledge. Some reporters felt that competition for space and audience were important obstacles, while others had difficulties with terminology, editors and problems finding and using sources. Commercialism was also perceived to be an obstacle.

Figure 1.

Barriers to improved medical reporting. Percentage of respondents who indicated strong agreement or agreement that the indicated constraint was a barrier to their improving the informative value of their work.

Barriers varied relative to the media in which the reporters worked (Table 2). Almost half (47.4%) of the journalists working at magazines felt that editors were an obstacle to preparing high qualitative reports. Lack of time to prepare a report was an obstacle most often to radio reporters (91.0%), while expert sources (70.6%), terminology (76.5%) and competition for audiences (58.8%) were noted as barriers most often by TV‐reporters.

Table 2.

Relationship between specific barriers and the dominant media in which journalists worked

| Barrier | Dominant media with highest score (% agree)* |

|---|---|

| Lack of time | Radio (91) |

| Lack of knowledge | Internet (75) |

| Lack of space | Radio (82) |

| Competition for space | Radio/TV (64) |

| Commercialism | Internet (64) |

| Terminology | TV/books (75) |

| Expert sources | TV (67) |

| Competition for audience | TV/books (75) |

| Editors | Magazine (47) |

*The percentage of respondents who reported worked predominantly in each of the specified media who either agreed or strongly agreed that this was a barrier for them.

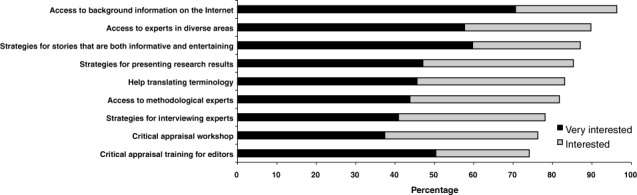

The respondents were asked about several suggested strategies for improving the informative value of their work (Fig. 2). Almost everyone wanted access to reliable, up‐to‐date background information on various topics available on the Internet and 90% were interested in access to experts in diverse areas of health and roughly the same proportion were interested in learning strategies to prepare more informative reports that are still entertaining and ‘saleable’. A high proportion (over 80%) were interested in strategies for presenting research results simply, in access to help translating scientific and medical terminology, and access to methodological experts. Most (>70%) were also interested in other possible aids to improving the informative value of stories about health and 79% were interested in participating in a trial to evaluate strategies to overcome the identified barriers.

Figure 2.

Interest in possible strategies to improve the informative value of medical reporting. Percentage of respondents who indicated they would be very interested or somewhat interested in the indicated strategies to help improve the informative value of their work.

Telephone interviews

Ten in‐depth interviews were conducted to include journalists from other countries and media and to broaden our understanding of journalists’ working situations. The respondents lived in Europe (Finland, Denmark, Germany, Bulgaria), Australia and Canada. The interviews showed that working conditions varied a lot among the reporters, primarily due to type of media, but also in relation to cultural and political circumstances. The health‐care situation in a given country also appeared as an important factor that impacts on the daily work of reporters.

The attitudes of experts who were contacted by journalists were a source of concern for reporters: ‘Half of them are really helpful and others are really afraid of bad press. One example was a dentist who said he only wanted to communicate via fax with me. Things like this are really not helpful.’ Others thought that the scientific jargon could be difficult: ‘Even though I have grown a bit used to it, sometimes the vocabulary is pretty obscure and you don't know what they are talking about.’

Lack of independent researchers was reported as an obstacle by several reporters: ‘Well, I am not sure if there are any left. Some few elderly professors in the universities, but they are getting rare. Even university research is getting more and more subsidized and when people know something that might be detrimental for the ones who subsidize them they will not talk. Or they will talk off the record, which is not very useful. That is a sad thing, not having any sources left.’ Another reporter claimed: ‘an expert that can give you the whole picture with risks, costs and benefits of a treatment for example, is a rare species of whom you should take good care if you find one.’

There was a consensus that the shortage of independent researchers and experts is a serious threat to reliable medical journalism, meaning that most reporters find it difficult to reveal someone's hidden interests and therefore could be tricked into writing a story with a less critical view.

Discussion

The results of this study represent the perceptions of experienced medical journalists. Although the response rate to our survey was low (22%, with no difference in response rate for those receiving email invitation or paper copy in mail), this needs to be viewed in light of the fact that the majority of people who were invited to respond were not eligible. The membership of the organizations that we contacted includes science writers who do not specialize in health, editors, and others who do not write a minimum of 10 articles about health per year. The breadth of the included sample and the consistency of the findings from the various methods that were used strengthen our confidence in the results.

The journalists included in this study were clearly defined as medical reporters and most of them were quite experienced. The results may not apply to less experienced reporters who do not specialize in medical reporting. Nonetheless, the participants were very heterogeneous. They represent a wide range of media, experience and level of education. They worked in countries with different cultural, economic, political and health‐care situations.

Despite the fact that the respondents’ backgrounds differed, there was a consensus on the three most prominent constraints: a majority agreed that lack of time, space and knowledge were major obstacles in their work. This is not surprising given that journalists must work quickly and be brief. Perhaps more unexpected is the self‐reported lack of knowledge, as the sample of reporters had been working for many years and had long experience with medical reporting. The steadily increasing flow of information in the medical field, the breadth of material that journalists must cover, and difficulties finding reliable sources could explain this.

Problems with sources were expressed as being of considerable importance. Many journalists reported difficulties finding experts willing to assist the media and to explain scientific jargon. Another problem is that experts often have conflicts of interest and these frequently are not revealed. 19 Interactions between journalists and experts has been described as a meeting between two professional cultures, with very little knowledge about the participants’ different roles and with great tension as a result. 6 , 20 In general, experts see their appearance in the media as an opportunity to educate and give advice to the public and therefore have a more paternalistic view than the journalist who emphasizes the holistic picture of a problem, take a patient's perspective and apply a critical view. This is well‐reflected in our study, both in comments from the survey and in the in‐depth interviews.

This problem could be dealt with using different strategies. One would be to try to reduce the cultural differences between the groups, which likely would be rejected by both journalists and experts, and would be difficult, at best, given differences in time scales, languages, audiences and motivations between journalists and experts. Another way of dealing with the problem would be to improve the communicating skills of the counterparts. The differences would still be there, but greater competency in dealing with them might improve journalistic processes and outcomes. There is a great need for a deeper understanding of each other's roles in the interview situation. The journalists in our survey did not, however, have any expectations of this happening. They rather emphasized the importance of their own improved education and interviewing skills, and had less interest in the situation of the interviewee. There is clearly a need for interventions that are targeted at both groups – experts and journalists. 21 The different solutions were discussed both in the focus groups and in the telephone interviews.

Another important obstacle to improving the informative value of medical reporting is the attitudes of editors. These people seldom have any higher education in medicine or health matters, nor have they understanding of the scientific process as a whole. Many respondents in our study would welcome training for editors in critical appraisal. Meanwhile, they indicated that editors would be unlikely to prioritize such training for themselves. How to reach editors is a considerable challenge, but potentially an important one to address. 15 , 22

The finding that there is great interest among journalists to improve the quality of their work by, for example, participating in a trial to evaluate strategies to overcome the identified barriers should be welcomed by the medical profession. However, to be effective interventions should be tailored to address identified barriers and the effectiveness of such interventions should be properly evaluated before being widely implemented. Simply offering advice and courses to journalists is unlikely to suffice.

Although this study did not set out to compare these groups, we nevertheless noted striking similarities in the barriers that medical journalists confront in trying to improve the informative value of their work and those that health professionals face in trying to ensure that the care they provide is based on current best evidence (Table 3). 23

Table 3.

Similarities between constraints on journalists and physicians

| Journalists | Physicians 23 | Explanations |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of time | Time constraints | Journalists have little time to prepare stories. Physicians have little time to read. |

| Lack of space | Journalists have little space in which to report complex information. Physicians have little time in which to explain complex information to patients. | |

| Lack of knowledge | Information overload | Journalists have difficulties mastering the breadth of topics they must cover. Physicians have difficulties coping with the flood of biomedical literature. |

| Competition for space | Standard of practice | Journalists are compelled to compete with colleagues for space for their stories. Physicians are compelled to adhere with local standards of practice (right or wrong). |

| Commercialism | Financial disincentives | The need for journalists to sell stories can conflict with providing balanced information. Financial incentives for physicians can conflict with providing good care. |

| Expert sources | Advocacy | Journalists are bombarded by sources with conflicts of interest. Physicians are bombarded by sources with conflicts of interest. |

| Terminology | Patient expectations | Journalists have difficulties making jargon understandable. Physicians have difficulties communicating with patients. |

| Competition for audience | Journalists may compete for their audiences’ attention. Physicians may compete for patients. | |

| Editors | Organizational constraints | Journalists are confronted with a number of organizational constraints, including editors, which can restrict their ability to improve the informative value of their work. Physicians are confronted with a number of organizational constraints that can restrict their ability to provide evidence‐based care for their patients. |

Conclusions

Health‐care professionals and researchers aim to improve the quality of health‐care. Ensuring that information about health‐care is valid is essential to this aim. Journalists have other priorities. Their aim is not to promote science or effective and efficient health‐care. Overcoming the constraints that journalists face will require efforts from both journalists and health‐care professionals, as well as an understanding of fundamental differences between the two cultures. A variety of strategies will likely be needed to address these constraints.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the BMJ staff for their assistance with convening the focus group of British journalists and all of the journalists who contributed to this study. The Norwegian Research Council funded this research.

References

- 1. Johnson T. Shattuck lecture – medicine and the media. New England Journal of Medicine, 1998; 339: 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schuchman M, Wilkes MS. Medical scientists and health news reporting: a case of miscommunication. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1997; 126: 976–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilkes MS, Kravitz RL. Medical researchers and the media. Attitudes toward public dissemination of research, Journal of the American Medical Association, 1992; 268: 999–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koshland DE Jr. Credibility in science and the press. Science, 1991; 254: 629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peters HP. The interaction of journalists and scientific experts: co‐operation and conflict between two professional cultures. Media, Culture and Society, 1995; 17: 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nelkin D. An uneasy relationship: the tension between medicine and the media. Lancet, 1996; 347: 1600–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Winsten JA. Science and the media: the boundaries of truth. Health Affairs, 1985; Spring: 5–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grilli R, Freemantle N, Minozzi S, Domenighetti G, Finer D. Mass media interventions: effects on health services utilisation (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, 2003, Issue 2. Oxford: Update Software. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kristiansen CM, Harding CM. Mobilization of health behavior by the press in Britain. Journalism Quarterly, 1984; 61: 364–370, 398. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nelkin D. Selling Science How the Press Covers Science and Technology. Revised edition. New York: WH Freeman and Co, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gorman C. The hope & the hype. Time, 1998; 151: 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gawande A. Mouse Hunt. Forget cancer. Is there a cure for hype? The New Yorker, 1998; (May 18) 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kolata G. A cautious awe greets drugs that eradicate tumors in mice. The New York Times, 1998; (May 3) A1. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shaw DL, Van Nevel JP. The informative value of medical science news. Journalism Quarterly, 1967; 44: 548. [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'keefe MT. The mass media as sources of medical information for doctors. Journalism Quarterly, 1970; 47: 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oxman AD, Guyatt GH, Cook DJ, Jaeschke R, Heddle N, Keller J. An index of scientific quality for health reports in the lay press. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 1993; 46: 987–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levi R. Bættre medicinjournalistik kræver bættre kællor. Vetenskap and praxis, 1998; 3–4: 8. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matz R. Health news reporting. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1997; 11: 948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moynihan R, Bero L, Ross‐Degnan D et al. Coverage by the news media of the benefits and risks of medications. New England Journal of Medicine, 2000; 342: 1645–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Semir V. Medicine and the media: What is newsworthy? Lancet, 1996; 347: 1063–1066. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Entwistle V, Watt IS. Judging journalism: how should the quality of news reporting about clinical interventions be assessed and improved? Quality in Health Care, 1999; 8: 172–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Michel K, Frey C, Wyss K, Valach L. An exercise in improving suicide reporting in print media. Crisis, 2000; 21: 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oxman AD, Flottorp S. An overview of strategies to promote implementation of evidence based health care In: Silagy C, Haines A. (eds) Evidence Based Practice. 2nd Edition. London: BMJ Publishers, 2001: 101–119. [Google Scholar]