Abstract

Objective Does a patient information booklet influence treatment for menorrhagia?

Design Randomized trial and a pre‐trial prospective cohort study.

Setting Gynaecology outpatient clinics in 14 Finnish hospitals.

Participants A total of 363 (randomized trial) plus 206 (cohort study) patients with menorrhagia.

Intervention An information booklet about menorrhagia and treatment options, mailed before the first visit to the outpatient clinic.

Main outcome measures Distribution of treatment modalities, knowledge about treatment options, satisfaction with communication with personnel and anxiety.

Results Treatment decision within 3 months was made more often in the intervention group than in the control group (96% and 89% respectively, P = 0.02). Oral medication was more frequently chosen, and newly introduced treatments (minor surgery, hormonal intrauterine system) were less frequently used in the intervention group (at 3‐month follow‐up 21% and 29%, respectively). The differences persisted at the 12‐month follow‐up. In the pre‐trial group, new treatment methods were less frequently chosen and used than in the control group. Additional information did not increase the number of surgical procedures used, improve knowledge, or influence satisfaction or anxiety.

Conclusion Additional information led to an increase in specific treatment decisions and changed the distribution of used treatments without increasing the number of surgical procedures. The study suggests that well‐informed women adopting an active role may counteract physicians’ emphasis on newly introduced treatments.

Keywords: decision aid, decision‐making, menorrhagia, patient education, patient participation, randomized trial

Introduction

Providing patients with additional information is believed to facilitate informed choices. A systematic review of randomized trials showed that decision aids have a varying effect on decisions. 1 In trials preceding major surgery, decision aids reduced the preference for more extensive coronary revascularization and mastectomy, but not prostatectomy. A decision aid for menorrhagia including a structured preference eliciting interview reduced hysterectomy rate, but not an information pack only. 2 Decision aids produced higher knowledge scores and more active patient participation in decision‐making, but did not influence anxiety or satisfaction with the decision‐making process. 1 The content of information rather than the medium used was found important by consumers. 3

Heavy menstrual bleeding, menorrhagia, is a common health problem among women of reproductive age. 4 While rarely life‐threatening, it can significantly impair quality of life. Resection and ablation of the endometrium, and the levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system have increased the number of treatment options, but oral medication and hysterectomy remain a common choice. Consensus about the most appropriate treatment is lacking, 5 and particular treatments are seldom unconditionally indicated or contraindicated. Ideally, women should base their decisions on their own values and preferences.

The main hypothesis of this study was that provision of an information booklet to menorrhagic women prior to visiting a gynaecology outpatient clinic would extend the variety of treatments used. Second, it is hypothesized that the additional information would increase the women's knowledge about treatment modalities. Anxiety and satisfaction in communication with personnel in gynaecology clinics were also investigated.

Participants and methods

Recruitment

The participating women were recruited from referrals by general practitioners or private gynaecologists to gynaecology outpatient clinics in 14 hospitals (four university teaching hospitals, five central and five local hospitals). The participants (age 35–54 years; cause of referral: menorrhagia or fibroids) were selected in two phases to ensure all women actually had heavy menstruation as the main gynaecological complaint, firstly by gynaecologists at the clinics using the information in referral documents and finally by a researcher (SV) at the research institute (STAKES) using the questionnaire information. The selection procedure is presented elsewhere. 6

Participants were recruited between January 1997 and September 1999. Between November 1995 and December 1996, a pre‐trial sample without intervention was collected, to be able to evaluate changes in clinical practice during the study period and any carry‐over effect of the spread of information.

This study was approved by the ethical committees of STAKES and participating hospitals. Women were informed that participation or non‐participation would have no consequence for their treatment. All women signed an informed consent form.

Randomization

Randomization was done in STAKES by a researcher (SV, who did not participate in the planning or concealment procedures) within 2 days of the baseline questionnaire arriving at STAKES, separately for each hospital in computer‐generated varying clusters, using sequentially numbered, opaque and sealed envelopes. Neither subjects nor study staff were blinded. Outpatient clinical staff were aware of a woman's participation in the study only if she mentioned it.

Intervention

Intervention consisted of an information booklet (25 A5 pages) about heavy menstruation and its treatment options, written by the authors in 1996 and revised by the gynaecologists in participating hospitals. The information was mainly derived from recent guidance to general practitioners in the UK about menorrhagia treatment. 7 Information about the hormonal intrauterine system in menorrhagia treatment were from published literature. 8 , 9 , 10 The booklet covered all relevant treatment options, including benefits and risks. The aim was to encourage menorrhagic women to consider different aspects of treatment and what outcomes they wanted. The content of the booklet is described in Box 1. It was mailed to the intervention group women at least 7 days before appointment at the gynaecology outpatient clinic. All women were treated and followed up using regular clinical protocols.

Table Box 1 .

Content of the information booklet (=intervention)

| Menstrual cycle |

| Causes of heavy menstruation |

| Indications for treatment |

| Diagnosis |

| Treatment modalities |

| Active observation |

| Non‐hormonal medical treatments (non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory drugs, tranexamic acid) |

| Hormonal medical treatments (progestines, contraceptive pills) |

| Hormonal intrauterine system |

| Removal of copper intrauterine device and progestine capsules |

| Minor surgery = destruction of endometrial lining, removal of single fibroid |

| Hysterectomy = removal of uterus |

| Encouraging women to consider the outcome they want from treatment and the issues important to them, and to discuss these with the outpatient clinical physician |

| Table of medical treatments |

Variables

The primary outcome measures were planned treatment at 3 months and actual treatment received 1 year after entering the study. Information on the treatments was gathered from medical records, and completed from the patients’ follow‐up questionnaires. Treatments were classified into (1) hysterectomy, (2) smaller surgical procedure, (3) hormonal intrauterine system, (4) oral medication, (5) change of birth control method and (6) no decision for treatment. The secondary outcome measures were level of knowledge about treatment methods, satisfaction with communication with the personnel in gynaecology outpatient clinics, and anxiety. An open‐ended question was used to list all treatment modalities known by the women. A sum score of feasible methods was calculated. Satisfaction was assessed using a five‐item sub‐scale of a validated scale developed by Ware et al., 11 and state anxiety by Spielberger's instrument. 12 , 13

The amount of menstrual bleeding, menstrual pain and perceived inconvenience as a result of bleeding were assessed by the questionnaire. Presence of pelvic pain or pressure, and regularity of the cycle were also included in the assessment questionnaire. 14

Treatment preferences were probed in the baseline questionnaire before the first outpatient clinical visit, and classified into hysterectomy or conservative treatment course. The method was modified from a preference measurement presented by Warner, 15 and is described elsewhere. 14

Data collection

Background characteristics, menstrual symptoms, treatment preference, knowledge about treatment options, and anxiety were measured before the first outpatient clinical visit. Follow‐up information up to 1 year was collected using two methods: (1) examination of medical record data, and (2) follow‐up questionnaires with three reminders at 3 and 12 months after entering into the study. Medical records covering the 1‐year study period included examinations and treatment(s) used, plus operation reports from all gynaecology clinics. At 3 months, women's knowledge about treatment options, anxiety and satisfaction with communication with personnel in gynaecology outpatient clinics were monitored.

Statistical analysis

The power calculation was based on information about the main health outcomes measured by Rand 36 instrument 16 and is reported elsewhere (S. Vuorma, unpublished data). A sample size of 180 per arm in randomized trial would give an 80% power (β = 0.20) to detect 10% difference between study groups with an α‐error of 0.5. All analyses assumed the intention to treat principle. Comparisons were made using the control group as reference. Group differences were analysed by comparing mean values and proportions. Statistical significance was tested by the chi‐square test, Fisher's exact test, and Student's t‐test. The Mann–Whitney U‐test was used to compare the medians of two groups regarding satisfaction with communication with personnel. Two‐tailed tests were used, and 0.05 was the critical value for statistical significance.

Results

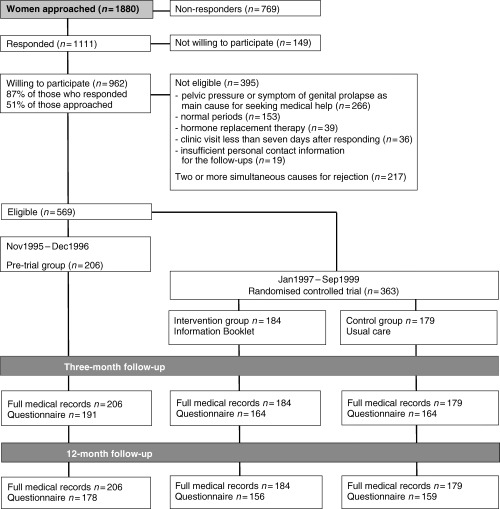

Of the 1880 women to whom the questionnaire were sent, 1111 responded and 962 were willing to participate (Fig. 1). However, 395 (41% willing participants) were not eligible because of symptoms other than heavy menstruation as the main cause for seeking medical care. The non‐eligible women were slightly older (45.2 years vs. 44.4 years, P = 0.003) than the study group, but were otherwise comparable. One woman in the control group used hormone replacement therapy and was randomized by mistake. She was included in the analyses.

Figure 1.

Trial profile.

The final sample in this study comprised 569 women: 363 in the randomized trial (184 in the intervention group, 179 in the control group) and 206 in the pre‐trial sample. The educational background of the study sample resembles that of the general population in these age groups according to the information from Statistics Finland.

The response rate at both follow‐ups was 100%, as all medical records were available. Follow‐up questionnaires were returned by 91% (n = 519) of women at 3 months and by 87% (n = 493) at 12 months. Women who did not return the 3‐month questionnaire (n = 50) had a higher level of anxiety (40 for non‐respondents, 36 for respondents, P = 0.01), but did not differ from other women in any other baseline variable measured, nor in planned nor actual treatments.

Baseline characteristics of the participants appear in Table 1. The proportion of women perceiving their periods as very heavy was lower, and having irregular periods was slightly higher, in the pre‐trial than the control group. Otherwise, the study groups did not differ at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the women with heavy menstrual bleeding before the first outpatient clinical visit (n = 569) [Mean values (SE) or numbers (%)]

| Characteristics | Intervention | Control | Pre‐trial | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 184 | n = 179 | n = 206 | control vs. pre‐trial | |

| Severity and inconvenience of menstrual symptoms | ||||

| Inconvenience due to heavy bleeding (scale 5–25) | 19.2 (0.34) | 19.5 (0.35) | 19.2 (0.32) | 0.5 |

| Menstrual pain (scale 0–12)* | 4.9 (0.27) | 4.7 (0.27) | 4.4 (0.25) | 0.3 |

| Periods perceived as very heavy (%) | 112 (61) | 115 (64) | 111 (54) | 0.04 |

| Irregular periods (%) | 42 (23) | 46 (26) | 71 (34) | 0.06 |

| Pelvic pain or pressure (%) | 86 (47) | 80 (45) | 85 (41) | 0.5 |

| Background factors | ||||

| Age (years) | 44.5 (0.31) | 44.3 (0.31) | 44.3 (0.29) | 0.9 |

| Sterilized (%) | 85 (46) | 84 (47) | 80 (39) | 0.1 |

| Education less than 12 years (%) | 104 (57) | 94 (53) | 112 (54) | 0.7 |

| Unemployed or retired, Fischer two‐sided test (%) | 19 (10) | 16 (8.9) | 32 (16) | 0.06 |

| Pre‐treatment preference | ||||

| Hysterectomy (n = 249) (%) | 91 (49) | 80 (45) | 78 (38) | 0.4 |

| Conservative treatment course (n = 212) (%) | 58 (32) | 66 (37) | 88 (43) | 0.2 |

| Unclear preference (n = 108) (%) | 35 (19) | 33 (18) | 40 (19) | 0.5 |

| Anxiety (scale 20–80)† | 36.1 (0.80) | 35.9 (0.81) | 37.0 (0.76) | 0.3 |

*Scale for menstrual pain was calculated by multiplying the intensity of pain (0 for no pain to 6 for heaviest possible pain) by the frequency of pain (0 for never to 2 for every period).

†Higher score indicates higher level of anxiety.

The distributions of treatment modalities at 3 and 12 months are presented in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. At the 3‐month follow‐up, 18% in the intervention group and 8% in the control group had received a prescription for oral medication (P = 0.007). The proportion of new treatment methods (minor surgery or hormonal intrauterine system) was slightly lower in the intervention than in the control group at 3 months (21% vs. 29%, respectively, P = 0.06) (Table 2) and significantly lower at 12 months (16% vs. 26%, P = 0.03) (Table 3). At 3 months, the proportion of women with treatment still undecided in the outpatient clinic was lower in the intervention than the control group (4% vs. 11%, P = 0.02) (Table 2). At 1 year, the number of surgical treatment modalities used did not differ between the two study groups (Table 3).

Table 2.

Treatment planned up to 3 months after first visit to the gynaecology outpatient clinic [Values are numbers (%)]

| Intervention | Control | Pre‐trial | P‐values | C vs. PT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 184 | n = 179 | n = 206 | C vs. I | ||

| Treatment plan | 0.007 | 0.01 | |||

| Hysterectomy | 99 (54) | 85 (49) | 99 (48) | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Minor surgery or LNG‐IUS | 38 (21) | 52 (29) | 35 (17) | 0.06 | 0.005 |

| Change in birth control method | 4 (2) | 3 (2) | 6 (3) | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Oral medication | 33 (18) | 15 (8) | 39 (19) | 0.007 | 0.003 |

| No treatment decision | 8 (4) | 20 (11) | 24 (12) | 0.02 | 0.9 |

| No visit to outpatient clinic | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.4 | 0.7 |

I = intervention group, C = control group, PT = pre‐trial group, LNG‐IUS = hormonal (levonorgestrel) intrauterine system.

Table 3.

Actual treatment received up to 12 months after first visit to the gynaecology outpatient clinic [Values are numbers (%) unless otherwise stated]

| Intervention | Control | Pre‐trial | P‐values | C vs. PT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 184 | n = 179 | n = 206 | C vs. I | ||

| Actual treatment | 0.08 | 0.0004 | |||

| Hysterectomy | 98 (53) | 88 (49) | 107 (52) | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Minor surgery or LNG‐IUS | 30 (16) | 46 (26) | 23 (11) | 0.03 | 0.0002 |

| Other | 54 (29) | 44 (25) | 74 (36) | 0.3 | 0.02 |

| No treatment and no visit to outpatient clinic | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | ||

| Number of surgical procedures used within 1 year [mean (SE)] | 0.70 (0.04) | 0.73 (0.04) | 0.61 (0.04) | 0.6 | 0.01 |

I = intervention group, C =control group, PT = pre‐trial group, LNG‐IUS = hormonal (levonorgestrel) intrauterine system.

New treatment methods (minor surgical procedure or hormonal intrauterine system combined) were less frequently favoured, and oral medication more frequently, in the pre‐trial than the control group (Table 2). These differences persisted over the 1‐year study period (Table 3). Surgical treatment modalities and the hormonal intrauterine system were less used in the pre‐trial than in the control group (Table 3). The number of treatment methods mentioned increased less in the pre‐trial than in the control group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Change in the knowledge level, satisfaction with communication in gynaecology outpatient clinic, and change in anxiety*

| Intervention | Control | Pre‐trial | P‐values | C vs. PT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 164 | n = 164 | n = 191 | C vs. I | ||

| Increase in treatment methods mentioned (max 6) between follow‐up and baseline [mean (SE)] | 0.48 (0.102) | 0.45 (0.102) | 0.13 (0.095) | 0.8 | 0.02 |

| Satisfaction with communication with personnel in gynaecology outpatient clinics, scale 8–40 [median (Q1, Q3)] | 36 (30, 39) | 36.5 (31, 40) | 35 (31, 39) | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| Change in anxiety level (level of anxiety at baseline subtracted from that at 3 months) [median (Q1, Q3)] | 1 (−5, 5) | −1 (−4, 4) | −1 (−8, 3) | 0.3 | 0.08 |

I = intervention group, C = control group, PT = pre‐trial group.

Student's t‐test for mean values and Mann–Whitney U‐test for medians.

*Women who gave follow‐up information at 3 months (n = 519).

No between‐group differences were detected in the change in anxiety, satisfaction or knowledge level (Table 4).

Excluding the woman on hormone replacement therapy did not notably influence any of the results.

Discussion

This study showed that providing an additional information booklet to women suffering from menorrhagia influenced treatment choices: they were more likely to have a treatment decision made during the three months following referral to an outpatient clinic, and they received a prescription for medication more frequently. The better informed women used newly introduced treatment modalities less frequently than those in the control group. Additional information had no impact on the number of surgical treatments used, anxiety, satisfaction with communication with personnel in gynaecology outpatient clinics, or knowledge about treatment methods.

The finding that additional patient information decreased the use of new treatment modalities accords with previous reports that decision aids reduced the preference for more invasive surgery. 1 Further, the finding that information booklet had no impact on hysterectomy rate is in line with Kennedy's results of information pack alone. 2 The women in the pre‐trial cohort, compared with those in the control group, received minor surgery or hormonal intrauterine system less frequently, and prescriptions for oral medication more frequently, possibly reflecting a change in clinical practice over the study timeframe.

Doctors often drive the introduction of new medical technology. In the present study, the information booklet covering all treatment modalities may have counteracted the physician‐driven emphasis on newly introduced treatments. Better‐informed women may place more weight/emphasis on side‐effects and risks than is normally the case.

The equal increase in knowledge in the intervention and control groups might be due to the limitations of measuring knowledge by open‐ended questions. The other explanation is the carry‐over effect in information flow: the change in the decision‐making process of the intervention group may have altered the physicians’ way of negotiating with their patients. The difference in the change in knowledge about treatment modalities between the pre‐trial and control groups may be due to the increase in treatment options during the study period.

This study focused on a simple type of decision aid, an information booklet. The method is inexpensive and easy to prepare and access. It was not possible to assess whether the booklet was actually read, although the intervention women stated it was useful and that it helped them consider treatment options. The higher proportion of women who had treatment decided in the intervention group implies a true change in decision‐making, probably due to enhanced ability to define their own treatment preference. Additional information could potentially benefit women when they first consult any doctor for menorrhagia. However, a decision aid is important in specialist outpatient clinics with a wide variety of treatment modes. An information booklet has a place among more complex types of decision aids as it can be provided to all patients independently of their skills with and access to technical equipment.

Conclusion

The women regarded the information booklet as useful, and it led to an increase in specified treatment decisions. Additionally, newly introduced treatments were used less and oral medication more than among control group women. Such changes are probably due to women's enhanced ability to define their own treatment preference. This phenomenon may lead to more common deviation from physicians’ preferences at a time when new treatment modalities are emerging.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participants in the survey. We also thank the staff of the gynaecological clinics in the co‐working hospitals: Hyvinkää, Jorvi, Kätilöopisto, Lohja, Peijas and Seinäjoki Hospitals, Kanta‐Häme, Keski‐Suomi, Kymenlaakso and Pohjois‐Karjala Central Hospitals, and the University Teaching Hospitals of Kuopio, Oulu, Tampere and Turku. Special thanks to Raimo Kekkonen his valuable and critical comments. This study was supported by STAKES, the National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health, and Doctoral Programmes of Public Health of Helsinki and Tampere Universities.

References

- 1. O'Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V et al. Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systemic review. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319: 731–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kennedy ADM, Sculpher MJ, Coulter A et al Effects of decision aids for menorrhagia on treatment choices, health outcomes, and costs; Journal of American Medical Association, 2002; 288: 2701–2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coulter A, Entwistle V, Gilbert D. Sharing decisions with patients: is the information good enough? British Medical Journal, 1999; 318: 318–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Market Opinion and Research International, MORI. Women's Health in 1990.Research study conducted on behalf of Parke‐Davies Research Laboratories. Southampton: Market Opinion and Research International, ; 1990.. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coulter A, McPherson K, Vessey M. Do British women undergo too many or too few hysterectomies? Social Science & Medicine, 1988; 27: 987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vuorma S, Rissanen P, Aalto A‐M, Kujansuu E, Hurskainen R, Teperi J. Factors predicting choice of treatment for menorrhagia in gynaecology out‐patient clinics. Social Science & Medicine, 2003; 56: 1653–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Effective_Health_Care . The management of menorrhagia. Effective Health Care 1995: Bulletin No 9. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scholten PC, Levonorgestrel IUD. Clinical Performance and Impact on Menstruation. Utrecht, Holland: University of Utrecht, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luukkainen T, Lähteenmäki P, Toivonen J. Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device. Annals of Medicine, 1990; 22: 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Andersson K, Rybo G. Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device in the treatment of menorrhagia. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 1990; 97: 690–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ware JE, Jr, , Snyder MK, Wright WR. Defining and measuring patient satisfaction with medical care. Evaluation and Program Planning, 1983; 6: 247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Poikolainen K, Aalto‐Setälä T, Pitkänen T, Tuulio‐Hendriksson A‐M, Lönnqvist J. The mental symptoms with related factors of young adults [Nuorten aikuisten psyykkiset oireet ja niihin liittyvät tekijät]. Kansanterveyslaitoksen tutkimuksia KTL 1997: A2. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vuorma S, Teperi J, Hurskainen R, Aalto A‐M, Rissanen P, Kujansuu E. Correlates of women's preferences for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. Patient Education and Counseling, 2003; 92: 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Warner P. Preferences regarding treatments for period problems: relationship to menstrual and demographic factors. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 1994; 15: 93–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36‐item Health Survey 1.0. Health Economics, 1993; 2: 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]