Abstract

Objective Relatively little research has been carried out on the health and supportive care needs of rural women living with breast cancer. In this study, results from a Canadian focus group study are used to highlight issues of importance to rural women.

Setting and participants A total of 276 rural women with breast cancer divided into 17 focus groups participated in the study conducted across Canada. A standardized protocol for discussion was employed. Issues of access to information, support and services were discussed, with women describing their experiences in trying to find appropriate programmes and services.

Main results The major theme identified through analysis of qualitative data was ‘becoming aware of and/or gaining access to health care information, support and services.’ Other major themes included: (1) dealing with isolation; (2) having to travel; (3) feeling the financial burden and (4) coping with changing work.

Conclusions Rural women with breast cancer have supportive care challenges related to their circumstances. A series of recommendations were generated through the consultation process which are contributing to the development of a national strategy focusing on the development and extension of programmes for rural women with breast cancer. Although the research on the project was not to specified standards, and suffered from less attention than community capacity building and advocacy, it proved to be of worth and revealed potential benefits from collaborations between researchers and community organizations.

Keywords: breast cancer, focus groups, information, rural, services, supportive care

Introduction

Diagnosis of breast cancer is difficult for women, regardless of where they live. Within Canadian urban centres, a wealth of resources, programmes and services have been created to help women meet their information and support needs. But this is not the case for women living in rural and northern areas.

Relatively little research has been conducted on the general health care needs and experiences of rural women, or on the experiences specific to living with breast cancer. Most studies previously conducted with rural women with breast cancer have focused on issues of access and utilization. Women in rural areas in Australia 1 and the USA, 2 , 3 compared with urban women, have been more likely to choose modified radical mastectomy than breast‐conserving treatment. Canadian studies have also reported differences in women's access to surgery and other treatments. 4 , 5 Breast‐conserving surgery is more readily available in teaching hospitals in urban settings than in smaller centres where rural women are likely to go for treatment. In addition, a choice of breast‐conserving surgery has implications for rural women having to travel to an urban centre for radiation treatment.

Research has also shown disparities between urban and rural women in terms of access to mammographic screening. 6 , 7 In Alberta, for example, 40% of women live at least 50 km away from major centres, and women who had to travel 1–3 h from screening centres are half as likely to have had a mammogram. 8 , 9 While recent debates about the effectiveness of mammography complicate the interpretation of these results, it is nevertheless still the policy in Canada to encourage women over 50 years of age to seek regular screening. Thus, arguably, women in rural areas are at a disadvantage.

Few studies have analysed the broader range of issues perceived by women with breast cancer who live in rural areas. White et al. 10 highlighted the information needs of rural Michigan women with breast cancer in the months following diagnosis. Family physicians, oncologists and nurse practitioners were often the only sources of information for women, as many did not have access to libraries and other resources. Wilson 11 reported that breast cancer survivors living in rural Washington communities needed to be educated more about their disease and provided more emotional support after diagnosis. Koopman et al. 12 reported a higher level of helplessness/hopelessness among rural survivors in coping with breast cancer (than had been reported in previous studies with non‐rural samples). Research conducted in Australia by McGrath et al. 13 , 14 highlight additional social difficulties that women experienced as a result of living in a rural community. They reported that rural women had significant financial burdens related to travel, childcare responsibilities and changes to work. Australian rural women expressed concerns about being a financial and emotional burden on their partners. When women worked on farms, or were self‐employed, financial concerns were exacerbated.

There have been no prior Canadian studies that assess the needs and experiences of rural women with breast cancer. Lack of data has made it difficult to (1) clearly identify support needs; (2) assess whether these needs are being met and (3) decide how best to improve the circumstances of rural women with breast cancer.

In 2001, the Canadian Breast Cancer Network (CBCN) – a national network of breast cancer survivors – embarked on a unique and ambitious project. The project was designed to (1) build up the capacity of Canadian rural breast cancer survivors by mobilizing meetings and encouraging participation in policy setting and (2) elicit the perspectives of rural women living with breast cancer about their illness experiences, to help guide policy development. It is important to note that the CBCN is an organization primarily engaged in support and advocacy, and not with research. The research aspects of the project, while deemed important by project leaders, were clearly secondary to the mobilizing of women towards supportive and lobbying ends. Planning for research components, and systematic gathering of data, were thus compromised by the primary focus on community building. One important expression of this prioritizing was the invitation of the research team at the Ontario Breast Cancer Community Research Initiative (OBCCRI) to consult on the project only towards the end of the data‐gathering phase. While this was clearly less than ideal, our research team decided there was an important opportunity to link with a community consultation process. Additionally, like the CBCN organizers, we wanted to ensure that as much information as possible about the perspectives of rural women was gleaned from the consultation process.

Before proceeding, it is important to consider what is meant by ‘rural’, as the term has been used to refer to individuals living in a variety of situations/locations. The CBCN did not assume any particular definition, and women could decide whether to participate in the study, judging for themselves whether they fit the criteria for living in a ‘rural setting’. This decision was in keeping with the political agenda of maximizing the input of local women, empowering them to decide about their status rather than having an ‘Ottawa bureaucrat’ or some unknown researcher make the decision for them. Some women who participated in this project lived on farms, but others lived in, or on the outskirts of villages or hamlets, while a few others lived in towns or small cities.

Methods

Participants

Seventeen focus groups were conducted across Canada, with a total of 276 women attending these meetings. Participants were accrued from breast cancer support groups, and through referrals from breast screening clinics, oncologists, nurses, allied health professionals, Canadian Cancer Society branches, provincial breast cancer networks and members of the CBCN Board of Directors. Focus groups were hosted in Newfoundland (Corner Brook and Deer Lake); New Brunswick (Sussex); Prince Edward Island (Charlottetown); Nova Scotia (Halifax); Quebec (Quebec City × 2); Ontario (Stratford, Toronto, Sharbot Lake); Manitoba (Gimli, Winnipeg); Saskatchewan (Saskatoon, Swift Current); Alberta (Edmonton); British Columbia (Prince George) and the Yukon (Whitehorse). Local consultants facilitated the majority of groups, with a CBCN staff person (not trained in research methods) assisting with organization and recording.

Each focus group meeting was audiotaped and notes were also taken. Quality of the recorded tapes varied. Those that were audible were transcribed while others proved unusable. The facilitators were asked to follow a pre‐designed interview guide to focus the discussion within the following broad domains: (1) pre‐diagnosis and diagnosis; (2) post‐diagnosis and treatment and (3) post‐treatment and supportive care. A brief demographic form (including age, geographical location and diagnosis/treatment information) was provided to participants, along with an evaluation form about the focus group process. Facilitators did not always remember to ask participants to complete the forms, and when they did, participants sometimes were preoccupied with other end‐of‐meeting conversations, and failed to comply. Following each focus group meeting, facilitators were asked to complete a standardized report documenting the most notable themes and quotes from the discussions. The quality (and content) of reports varied considerably across facilitators, with several refusing to follow the prescribed format.

After the consultations were completed, and analysis of the findings written up, participants were provided with a draft report (as were other members of relevant stakeholder organizations) and asked to provide feedback about its accuracy and relevance.

Analysis

The plan for analysis of data was created and implemented by our team of researchers from OBCCRI, after discussions with CBCN staff about the data they were gathering. A variety of sources (i.e. demographic forms, facilitator reports, evaluation forms and focus group audiotapes) were utilized to investigate the perspectives of women who participated in the focus groups across Canada. Analysis of demographic materials and evaluation forms were processed utilizing Microsoft Excel. NVivo (a qualitative data software program) was employed to help analyse the facilitators’ notes and transcribed texts from selected focus groups.

Thematic analysis was conducted using the facilitators’ reports and minutes, as well as focus group transcripts from usable tapes. Issues and concerns were coded initially in terms of content and proceeded through identification of larger theme categories. To ensure reliability, audiotapes of focus group were reviewed by members of the research team to ensure that quotes and themes appearing in the facilitators’ reports and minutes correlated with verbatim material.

The initial round of analysis resulted in two types of data, one related to the issues faced by women with breast cancer across the continuum of care and the other related to needs and issues that were distinct to the rural setting. The information provided about issues across the care continuum, while rich and important, reflected and confirmed previous findings about the information/education and support needs of women with breast cancer. 15 , 16 , 17 The study team decided to focus additional analysis and the presentation of results on aspects specific to the rural context.

Quantitative results

Selected demographic characteristics

Of the 276 focus group participants, 157 (57%) filled‐in a demographics form (Table 1). Most (72%) participants who responded to an item about age were 50 or older at the time of forming the focus group, although far fewer (40%) were over 50 years when they were diagnosed. Most (76%) were either married or living with a partner, and had one or more children (91%). The vast majority (86%) of those responding to an item about ethnicity specified that they were Caucasian. A minority of women (36%) classified their residence as a farm, country home or village, while 63% classified their residence as a town or small city.

Table 1.

Demographic and treatment/illness variables (n = 157)

| Age (n = 155) | |

| <50 years | 28% |

| 50+ years | 72% |

| Marital status (n = 152) | |

| Married/common law | 76% |

| Other | 24% |

| Ethnicity (n = 98) | |

| Caucasian | 86% |

| Other | 14% |

| Time since diagnosis (n = 153) | |

| ≤2 years | 29% |

| 2–6 years | 42% |

| 6+ years | 29% |

| Recurrence (n = 137) | |

| Yes | 18% |

| No | 80% |

| Unsure | 2% |

Distance to treatment sites and services

Travel information was reported by women involved with the project in a variety of ways. To provide a uniform method of describing travel, reports were translated into number of hours to arrive at destination (Table 2).

Table 2.

Breakdown of hours travelled for treatment (1 h = 60 km)

| Distance in km | Surgery location | Chemotherapy location | Radiation location | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| <1 h | 74 | 47 | 66 | 51 | 17 | 13 |

| 1–3 h | 37 | 24 | 28 | 22 | 27 | 21 |

| 3–10 h | 24 | 25 | 17 | 13 | 40 | 32 |

| 10+ h | 15 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 37 | 29 |

| n = 157 | n = 129* | n = 126* | ||||

*Variations in sample size are due to women's differing treatment regimes.

Surgery

Almost half (47%) of the women had to travel >1 h for surgery while 25% travelled for more than 3 h. Some of the women who travelled such longer distances had access to local surgical services, but chose to travel to cities where they hoped to receive a better quality of service.

Chemotherapy

Half (51%) of the women who required chemotherapy in this project required <1 h travel time to receive treatment, with a minority (21%) having to commute more than 3 h. Some women had to travel to different settings, depending on where they were in the treatment cycle. During initial treatment they had to travel to regional centres, whereas further along in their course of treatment they were able to receive care closer home. Many women commented that their oncologists did try to arrange to have local hospitals provide chemotherapy whenever possible.

Radiation treatment

Most (61%) of the women who required radiation treatment had to travel for more than 3 h. As a result of the extensive distances between women's homes and their radiation treatment site, many women were required to stay in urban centres for the duration of their treatment regime.

Qualitative results and discussion

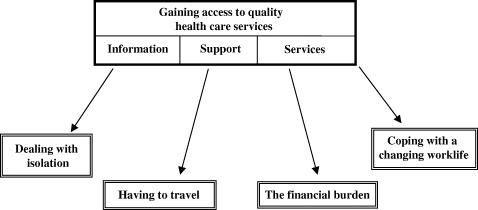

While focus groups varied in terms of the depth and breadth of discussion concerning rural issues, most provided detailed descriptions of specific rural issues confronting women dealing with a breast cancer diagnosis. The major theme identified through the analysis was ‘becoming aware of and/or gaining access to health care information, support and services.’ Results directly related to this overarching theme will be presented first, followed by other themes, including: (1) dealing with isolation; (2) having to travel; (3) feeling the financial burden and (4) coping with changing work (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework of distinct rural themes

Issues of access to information, support and services were discussed openly and repeatedly in all the focus groups, with women describing their experiences in trying to find appropriate programmes and services. Too often, information about resources and/or services was non‐existent, outdated or unhelpful. The process of becoming aware of programmes and services seemed a gradual process for most women, involving extensive, time‐consuming and stressful searching. Women were often disappointed about the types and levels of services offered locally or regionally, and they often compared their situations negatively with urban women.

Information

Across all the focus groups, women discussed concerns about difficulties accessing information locally. As a result, rural women relied particularly on physicians for information.

We live so far away from information.

There's no information in small towns.

Libraries are not well stocked or current.

Support

Many of the women in the focus groups discussed the struggles in finding the support they needed for themselves and their families, highlighting the importance of being able to talk about what they were going through with those who were taking care of them. Most often they found this type of support among family and friends. Some, although certainly not all, felt that the rural setting increased the possibility of support.

Friends and family play a significant information sharing and support role in the rural area.

Tightly knit communities can be a source of support.

While breast cancer support groups are less likely to be available in rural settings, many of those participating in the focus groups had nevertheless attended one (this being a function of the sampling strategy). Most had found it helpful. However, there was considerable discussion about the difficulties in establishing groups that are convenient for rural women.

Support groups are necessary, but in small towns/cities and rural areas they are hard to organize and keep going.

The problem with organized, community based support groups is that there are so few of them, and so few people wanting to join such a group at any particular time. Another problem is having a suitable facility.

Women perceived that facilitators for rural support groups often did not have the type of training they needed and they wondered if urban groups had more skilled leadership. Dealing with cancer‐related issues was seen as too difficult for untrained women.

Support group leaders should be trained in grief and loss.

Some of the support that women sought, and had difficulty finding, had to do with meeting their family's needs. The additional strain of running a home and parenting while coping with breast cancer diagnosis and treatment was often commented upon in the focus groups. Again, this concern was emphasized as being particularly difficult within a rural context, where services were rare and/or difficult to access. When women were away getting treatment for extended periods, these issues were gravely exacerbated.

There's a need for practical support, bringing food, taking children to activities, getting costumes/uniforms for kids activities, taking (me) out, providing transportation, etc.

I needed home support during my treatments. It wasn't possible.

Many of the women participating in this project spoke of the pressures put on their families by their illness, and on their perception that family members also needed support. They argued for the importance of having professional services available to family members at cancer treatment centres.

I was oblivious to my family's needs. They needed support.

Women often commented that they wished they had access to supportive care programmes run by health professionals or trained peers.

I was jealous when I heard what Wellspring [urban psychosocial resource program] has to offer, nutritional support, exercise groups… we don't have anything remotely like that.

Services

Women in all the focus groups spoke about issues of access to necessary services, including family doctors, cancer specialists, screening centres, and treatment centres.

Some women have no family doctor. No choice of doctors, and doctors with very large caseloads.

Around here there's a lack of options, re‐reconstruction, prosthetics, new drugs, etc.

The issue of access to local physicians was seen as particularly critical in the rural context, as women rely more heavily on their physicians in the absence of other informational and professional options.

Those living in rural communities rely heavily on their local health care providers for assistance with decision‐making and support.

Even when women had the access they wanted to local family physicians, poor communication from cancer treatment centres and specialists to family physicians often meant that the women could not get the informed help they needed.

My GP was left out of the loop by the specialist.

Once rural women are back home, they are out of the system. Oncologists are leaving and women are getting dropped.

There were some complaints from women that certain treatments might potentially be offered more often in local centres than was occurring.

Doctors seem to send patients to bigger hospitals, even if treatment is available locally. Small hospitals that could take chemo orders don't get them.

Strong concerns were voiced across all the focus groups about issues of timing within the medical system. Women talked about long waits for tests followed by rushed decision‐making.

The system either moves too slow or too fast for rural women. There are issues regarding access to appointments, waiting time for, and travel time to, appointments. Things go more slowly from rural areas. However, once diagnosed, appointment time and treatment choices are scheduled quickly and women do not have enough time to make decision about surgeries/treatments.

Treatment decisions were frequently influenced by the women's rural context. Consistent with other studies, 4 , 5 findings from this project showed that a higher proportion of women chose mastectomy over lumpectomy. Their reason for pursuing mastectomy most often related to the distance involved in travelling for radiation treatment, with associated impacts on childcare/family responsibilities, finances and work.

I chose mastectomy over lumpectomy and radiation because I didn't want to disrupt the family.

When I was offered lumpectomy or mastectomy I elected mastectomy given the higher costs of being away from my family.

Women's experiences with hospital stay and post‐treatment follow‐up varied across the country. Many felt they were sent home too soon, given the distance they needed to travel home and the relative lack of medical/nursing supports available once they arrived home.

I had a mastectomy at 1 p.m. and was sent home by 6 p.m., and was in emergency at midnight, with complications.

There was no one locally available to remove tubes/bandages/stitches/drains.

Other themes

Dealing with isolation

Many of the women who participated in focus group discussions described having struggled with a sense of isolation, both in their home setting and in the urban setting where they received treatment. This was particularly pronounced for women who had to stay in an urban setting for extended periods in order to receive treatment. The initial experience was often one of feeling displaced from all the usual supports and contexts.

It was devastating to come to an unknown city. No friends, nothing to do.

The worst part of all was the radiation. It was a living hell. I spoke to my kids on the phone every night to tuck them in. My parents took care of them and I was all alone with nothing to do.

Often, over time, women made connections with other cancer patients in the cities where they were staying. But then when they returned home, it could feel like they were losing their hard‐won support network.

It was scary to be on my own [after completion of treatments]. I thought, ‘Now what do I do?’

I was lonely, especially when I returned home, as I left my supports behind in the city where I had my treatment.

Isolation continued for some of the women unable to find support locally. Sometimes this was because of a perceived lack‐of‐interest from others, while in other situations women decided to isolate themselves in order to avoid being the topic of gossip.

There are problems with lack of anonymity and confidentiality in rural areas. Nurses in town would often tell everyone.

Just because I live in a rural area, does not mean I am close to my neighbours. I don't want them to know about me, and that I have breast cancer.

Having to travel

As already noted, many of the women participating in the focus groups reported having to travel to cancer centres in order to access treatment. For many this involved extensive distances, by car, plane, train and/or bus.

I traveled 400 kilometers (one way) for chemo, and 300 kilometers (one way) to see my surgeon and for surgery and for follow‐up appointments.

Travelling to the city on the late night bus for an early morning appointment (10 hours bus ride) is time‐consuming, exhausting, and then being booked in a day room and expected to travel back on the same day…

Many women talked about difficulties related to driving, including bad weather conditions, driving at night, and the fear of driving in an unknown city. Many felt that cancer centre staff gave little attention to patients’ travel challenges when appointments were being booked.

Winter driving makes travelling impossible.

I'm reluctant to drive at night, but I had to.

Women also talked about problems involved in arranging transportation, especially those women who didn't have their own vehicles.

I didn't have a vehicle, so I had to arrange drivers.

If you don't drive, you won't get there. There is no other transportation.

Feeling the financial burden

Concerns about finances were discussed in all of the focus groups. While the Canadian health care system is purported to provide universal coverage, the reality is that there are many gaps. Economic realities of rural life added extra urgency to the concerns voiced by women in this project.

All this financial stress on top of the disease. ‘Will I be able to afford the rent?’ is a common question I asked.

Extreme poverty, 15 weeks of unemployment, and then nothing.

A common frustration linked with finances related to reimbursement. Many women referred to financial inequities (compared to urban patients) and to limited/scarce assistance.

Living 3 h away was not considered remote enough to warrant lodging or travel reimbursement.

No access to subsidies for travel to treatment, or anti‐nauseant medication if your income is over $15 000.

Other non‐reimbursable costs that often came as a surprise to the women included phone calls from urban treatment centres, required side‐effect medications, and prosthetics.

Cost of phone calls and prescriptions was high.

I couldn't afford the only anti‐nauseant that would work for me.

There were hidden costs involved for those who had to stay in the city for treatment.

I had no money for childcare. The kids had to go away for two week periods with my mother‐in‐law, and the youngest child had to go to a different kindergarten during those periods.

Coping with a changing work‐life

Many women who participated in the focus groups expressed needs and issues associated with employment. The women emphasized the uniqueness of employment practices in rural communities where work options rarely include a full‐time salary with a single organization. Many women were working multiple part‐time jobs, all without benefits and/or job security. Others were self‐employed. These women were left without options when they needed time off for sickness or to travel for treatments.

Many jobs in the north are part‐time, or involve people who are working for small businesses, or are self‐employed without benefits.

Employers want to be rid of women with breast cancer since they think you won't be reliable or you will get sick again.

Recommendations

Women attending the focus groups were encouraged to make suggestions on how best to meet the needs of rural women with breast cancer. They expressed strong determination to change the nature of the breast cancer experience for women diagnosed in the future.

Each focus group participant was asked to list their personal top three recommendations, based on what they heard discussed during the group. Recommendations fell into four main categories: information, support, medical services, and financess.

Information

A frequent recommendation related to information was to encourage doctors to make a standardized information package available to women at the point of diagnosis. Such an information package would be sensitive to the rural context and might include: medical resources, contact information about breast cancer survivors, support group information, information about professional psychosocial support personnel, books, websites, and information on treatment and treatment side‐effects.

Some women reported that information packages were becoming available in their regions, but that the information was often not standardized, and that dissemination tended to be erratic.

Some women talked about wanting information in various formats (video, pamphlets, books). Others spoke of the need for information written especially for their spouses and/or children. Many women saw the need for better information/education as extending beyond breast cancer survivors and their families to include women who were well. Concerns about future generations of women were expressed through comments that younger women need to be properly educated about breast cancer. Many focus group participants recommended that education about breast health start in adolescence, and that young women learn about the need for breast self‐exam and mammography.

Support

The most common support‐related recommendation was to find ways to facilitate access of newly diagnosed women to another breast cancer survivor. Women noted that this peer support is critical for helping to minimize fears, normalize experiences, and offer a ‘survivorship’ perspective.

Other support recommendations made by the women related to access to services and programmes. Women recommended more programmes for rural areas.

Medical services

Many women participating in the focus groups strongly recommended improvements to the current Canadian health care system, so as to allow breast cancer survivors better access to high quality medical/nursing services, in a coordinated, patient‐sensitive manner. A specific recommendation supported by a substantial number of women was to have nurses specializing in oncology available within rural regions. Such nurses would be able to meet with patients to address health issues, thereby lowering costs and lightening the load for oncologists.

Another specific recommendation was to create networks of ‘patient navigators’ who could guide newly diagnosed women through the cancer care system. Many women thought that a patient navigator would make it more likely that any given woman would access available services in a timely way, thereby reducing unnecessary stress and anxiety.

Finances

Women in all of the focus groups were upset about costs incurred during breast cancer treatment. Women recommended that all expenses incurred be covered and that lower income women get special consideration, such as free prosthetics (replaced when appropriate).

Women also recommended overwhelmingly that travel‐related expenses be provided up‐front, so that they wouldn't be out‐of‐pocket and have to be reimbursed.

Validation of findings

Following the analysis of focus group findings, a draft report was written and sent, together with a feedback form and covering letter, to 266 breast cancer stakeholders across Canada. Stakeholders were asked to read the report and provide input. A total of 67 feedback forms were returned – for a 25% response rate. The forms included 11 scaled items, for which stakeholders were asked to indicate levels of agreement or disagreement. For the purposes of reporting findings, ratings are organized into categories of ‘agree’, ‘uncertain/neutral’ or ‘disagree’.

A high proportion of stakeholders agreed with each of 11 items that summarized study findings (Table 3). Agreement with these items corresponded to stakeholders’ responses to an open‐ended question in which they were asked to comment about the overall report. Almost all of the 32 responses to this item reinforced and validated points that had been made in the report or else offered suggestions about how rural women with breast cancer could be better served by the health care system. The feedback received from stakeholders thus strengthens the validity of the findings developed from the initial focus group study.

Table 3.

Stakeholder agreement with project findings

| % Agreed | Statement |

|---|---|

| 74 | Rural women with breast cancer have difficulties accessing high quality information in a timely manner |

| 84 | Rural women with breast cancer have difficulties accessing peer and professional support in a timely manner |

| 68 | Rural women with breast cancer have difficulties accessing appropriate medical and nursing services |

| 85 | Rural women with breast cancer have more difficulties than do urban women accessing high quality information, peer and professional support, and medical and nursing services |

| 81 | Dealing with social isolation is a major problem for rural women with breast cancer |

| 97 | Having to travel for treatment is a major problem for rural women with breast cancer |

| 89 | Inadequate financial programs create a major burden for rural women with breast cancer |

| 83 | Coping with a changed work life is a major problem for rural women with breast cancer |

| 98 | Standardized, and locally sensitive, information packages should be made consistently available to women with breast cancer in all regions of Canada |

| 98 | Systems need to be developed to better help newly diagnosed breast cancer patients living in rural areas navigate the health care system |

| 93 | Systems need to be put into place to ease the financial burden for rural women with breast cancer |

Discussion

We need to begin our discussion by acknowledging the constraints under which this project took place. Because of the late entry of the research team into the project, the organization and implementation of data gathering was less than ideal. The primary focus on community building made it difficult to meet the usual standards for research practice. Beyond these pragmatic aspects, we must also mention that the lack of a comparison group in the project makes it impossible to determine the uniqueness of experiences described by rural breast cancer survivors. Future research could help clarify this issue by providing comparisons between rural women and other women with breast cancer.

While we acknowledge the above difficulties, we nevertheless want to highlight the importance of efforts such as this to foster collaboration between community groups and researchers. Too often researchers are seen by community organizations as impractical and irrelevant. We wanted to be helpful under the parameters defined by the community organization. While we would argue a different, more proactive involvement for future projects (and, indeed, such an approach was possible for a subsequent collaborative project with CBCN about young women with breast cancer), the rural women's consultation was a great success – in large part because of the analysis of data and writing undertaken by the research team. From our perspective, while messy and problematic in some ways, this research was worth doing because it has facilitated a process whereby the experiences of ill people could be used to achieve practical outcomes to the benefit of future patients.

In conclusion, rural Canadian women with breast cancer have considerable unmet needs, including many issues related to access. Focus group participants strongly voiced their displeasure that urban women with breast cancer seem to be receiving better care and support. They argued for practical help that would make the treatment process more feasible. Daily living concerns such as travel, time away from work, home and childcare, need to be better addressed if there is to be hope for equitable care for women in rural communities. The recommendations that were generated through the seventeen focus groups organized by CBCN across Canada offer a variety of important ideas and suggestions, and are contributing to the development of a National Strategy focusing on the development and extension of programmes for rural women with breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

The project described in this paper was funded by the Community Capacity Building component of the Canadian Breast Cancer Initiative of Health Canada, and the Canadian Rural Partnership – Pilot Projects Initiative of Agriculture and Agri‐Food Canada. Thanks are due to the many women across Canada who participated in the consultation process.

References

- 1. Mastaglia B, Kristjanson LJ. Factors influencing women's decisions for choice of surgery for Stage I and Stage II breast cancer in Western Australia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2001; 35: 836–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hokanson P, Seshadri R, Miller KD. Underutilization of breast‐conserving therapy in a predominantly rural population: need for improved surgeon and public education. Clinical Breast Cancer, 2000; 1: 72–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elward KS, Penberthy LT, Bear H, Swartz DM, Boudreau RM, Cook SS. Variation in the use of breast‐conserving therapy for Medicare beneficiaries in Virginia: clinical, geographic, and hospital characteristics. Clinical Performance and Quality of Health Care, 1998; 6: 63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goel V, Olivotto I, Hislop TG, Sawka C, Coldman A, Holowaty EJ. Patterns of initial management on node‐negative breast cancer in two Canadian provinces. British Columbia/Ontario Working Group. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 1997; 156: 25–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iscoe NA, Goel V, Wu K, Fehringer G, Holowaty EJ, Naylor CD. Variation in breast cancer surgery in Ontario. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 1994; 150: 345–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hurley SF, Huggins RM, Damien JJ. Recruitment activities and sociodemographic factors that predict attendance at a mammograph. American Journal of Public Health, 1994; 84: 1655–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Siahpush M, Singh GK. Sociodemographic variations in breast cancer screening behavior among Australian women: results from the 1995 National Health Survey. Preventive Medicine, 2002; 35: 174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bryant HE, Desautels JE, Castor WR, Horeczko N, Jackson F, Mah Z. Quality assurance and cancer detection rates in a provincial screening mammography program. Work in progress. Radiology, 1993; 188: 811–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bryant HE, Mah Z. Breast cancer screening attitudes and behaviors of rural and urban women. Preventive Medicine, 1992; 21: 405–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. White NJ, Given BA, Devoss DN. The advanced practice nurse: meeting the information needs of the rural cancer patient. Journal of Cancer Education, 1996; 11: 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilson SE, Andersen MR, Meischke H. Meeting the needs of rural breast cancer survivors: what still needs to be done? Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 2000; 9: 667–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koopman C, Angell K, Turner‐Cobb JM et al. Distress, coping, and social support among rural women recently diagnosed with primary breast cancer. The Breast Journal, 2001; 7: 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McGrath P, Patterson C, Yates P, Treloar SP, Oldenberg B, Loos C. A study of postdiagnosis breast cancer concerns for women living in rural and remote Queensland. Part I: Personal concerns. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 1999; 7: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McGrath P, Patterson C, Yates P, Treloar SP, Oldenburg B, Loos C. A study of postdiagnosis breast cancer concerns for women living in rural and remote Queensland. Part II: Support issues. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 1999; 7: 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mills ME, Sullivan K. The importance of information giving for patients newly diagnosed with cancer: a review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 1999; 8: 631–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gray RE, Greenberg M, Fitch M, Sawka C, Hampson A, Labrecque M, Moore B. Information issues for women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Prevention and Control, 1998; 2: 57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gray RE, Fitch M, Greenberg M, Hampson A, Doherty M, Labrecque M. The information needs of long‐term survivors of breast cancer. Patient Education & Counselling, 1998; 33: 245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]