Abstract

Objective To evaluate the effects of a decision aid for menorrhagia on treatment outcomes and costs over a 12‐month follow‐up.

Design Randomized trial and pre‐trial prospective cohort study.

Setting and participants Gynaecology outpatient clinics in 14 Finnish hospitals, 363 (randomized trial) plus 206 (cohort study) patients with menorrhagia.

Intervention A decision aid booklet explaining menorrhagia and treatment options, mailed to patients before their first clinic appointment.

Main outcome measures Health related quality of life, psychological well‐being, menstrual symptoms, satisfaction with treatment outcome, use and cost of health care services.

Results All study groups experienced overall improvement in health‐related quality of life, anxiety, and psychosomatic and menstrual symptoms, but not in sexual life. Treatment in the intervention group was more active than in the control group, with more frequent course of medication and less undecided treatments. However, there were no marked disparities in health outcomes, satisfaction with treatment outcome and costs. Total costs (including productivity loss) per woman because of menorrhagia over the 12‐month follow‐up were 2760€ and 3094€ in the intervention and control group, respectively (P = 0.1). The pre‐trial group also had a significantly lower rate of uterus saving surgery compared with the control group, but no difference in costs because of menorrhagia treatment.

Conclusion Despite some differences in treatment courses, a decision aid for menorrhagia in booklet form did not increase the use of health services or treatment costs, nor had it impact on health outcomes or satisfaction with outcome of treatment.

Keywords: cost analysis, decision aid, menorrhagia, psychological well‐being, quality of life, randomized trial

Introduction

Decision aids are tools that help patients make informed choices and participate in treatment decision‐making, especially when more than one treatment option exists. They help to guide the patient and her/his doctor towards treatment that best addresses the patient's values and needs. 1 Decision aids come in a variety of formats, including leaflets, audiotapes, decision boards, group presentations, computer programs, interactive videos, websites and structured interviews, 1 , 2 or combinations of these. 3 The key component is information necessary for informed choice presented in a structured, unbiased and comprehensive format. It must allow for the patient's preferences, and help to incorporate these into the decision‐making process.

Previous studies on decision aids have covered a wide range of circumstances, from participating in a screening test to decisions on life‐threatening health conditions. 1 , 2 So far, only a few studies have included cost evaluation. 3 , 4 , 5 Among women with menorrhagia, two types of decision aids have been compared, an information pack, and that plus a structured interview conducted by a nurse. 3 The decision aids had no effect on women's health status. Those who received an information pack plus interview reported greater satisfaction with overall results compared with other women. Moreover, the decision aid plus interview was cost saving because of a lower hysterectomy rate. 3

A decision aid given to women with menorrhagia leads to an increase in specific treatment decisions and decrease in use of newly introduced treatments. 6 In the present study, we analysed the health and cost outcomes of using a decision aid booklet in a randomized trial with 1‐year follow‐up.

Participants and methods

Recruitment

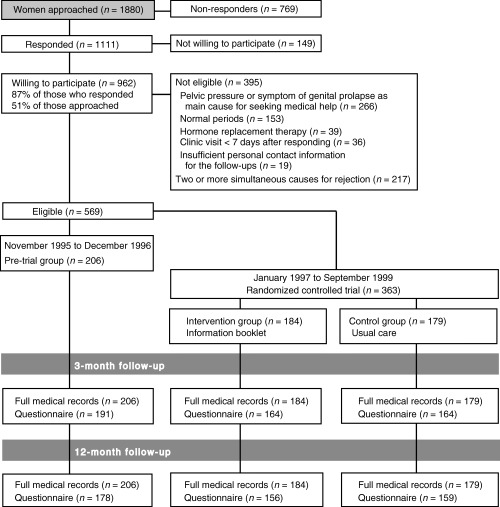

Potentially eligible women were identified from referral documents in gynaecology outpatient clinics of 14 hospitals (four university teaching hospitals, five central and five local hospitals). Preliminarily chosen women (age 35–54 years, cause of referral: menorrhagia or fibroids) all had heavy menstruation as the main gynaecological complaint. Final selection was based on the questionnaire information provided before the clinic appointment. Details on recruitment, selection procedure and participant flow are presented elsewhere 6 (see also Fig. 1). The mean age of the study sample was 44.4 years (range 35–54 years), 47% were sterilized, 55% had education less than 12 years, 63% perceived their menstrual flow as very heavy (vs. moderate heavy), 24% had irregular periods and 46% suffered also from pelvic pain or pressure.

Figure 1.

Trial profile.

The trial participants were recruited between January 1997 and September 1999. Between November 1995 and December 1996 we formed a pre‐trial sample without an intervention to record changes in treatment modalities and assess the magnitude of any carry‐over effect of disseminating information.

The study was approved by the ethics committees of STAKES and participating hospitals. Women were informed that their treatment in gynaecology clinics would accord with clinical standards. All signed an informed consent form.

Randomization

Eligible women were allocated to either the information group or ordinary care group by a STAKES researcher (SV) within 2 days of the baseline questionnaire arriving at STAKES. Randomization was performed in blocks with a varying block size separately for each hospital, using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. Outpatient clinic staff was aware of each woman's participation in the study only if she mentioned it.

Intervention

The information group received a decision aid booklet (25 A5 pages) about menorrhagia and its treatment options. The content drew on scientific literature 7 , 8 and up‐to‐date guidance for general practitioners on menorrhagia treatment. 9 All relevant treatment options were covered, including benefits and risks (see Box). The booklet encouraged women to consider different aspects of each treatment and the outcomes they preferred. It was mailed to the women at least 7 days before their gynaecology outpatient clinic visit.

Table Box .

Content of the decision aid booklet (intervention)

| Menstrual cycle |

| Causes of heavy menstruation |

| Indications for treatment |

| Diagnosis |

| Treatment modalities |

| Active observation |

| Non‐hormonal medical treatments (non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory drugs, tranexamic acid) |

| Hormonal medical treatments (progestines, contraceptive pills) |

| Hormonal intrauterine system |

| Removal of copper intrauterine device and progestine capsules |

| Minor surgery = destruction of endometrial lining, removal of single fibroid |

| Hysterectomy = removal of uterus |

| Encouraging women to consider the outcome they want from treatment and the issue important to them, and to discuss these with the outpatient clinic physician |

| Table of medical treatments |

Data collection

One‐year follow‐up information was collected by two methods: (i) a follow‐up questionnaire (three reminders) 12 months after entering the study, and (ii) examination of medical records, which were accessible to every woman based on their informed consent. The questionnaire response rate at 12 months was 87% (85, 89 and 86%, intervention, control and pre‐trial group respectively). The dropouts (n = 76) did not differ from other women in any baseline variable, nor in actual treatments.

Variables

Health outcomes were measured using standard validated scales when available. The primary outcome was general health status measured using RAND‐36, 10 , 11 and a visual analogue scale (VAS 0–100). Worst and best possible perceived health formed each end of the scale. In both scales, higher score indicates better health. Anxiety was measured by 20‐item state anxiety scale. 12 Psychosomatic symptoms were measured by an 18‐item questionnaire scale. 13 Sexuality‐related factors were assessed by the McCoy sex scale. 14 In these scales, higher score indicates more symptoms or problems or higher satisfaction.

Menstrual pain, perceived inconvenience because of bleeding, regularity of the cycle, and the existence of pelvic pain or pressure were asked. 15

Using a VAS (0–100), women were asked to score their satisfaction with the outcome of treatment. The worst and best possible outcome formed each end of the scale.

Data on use of hospital services (operations, inpatient days, procedures, outpatient visits), medication, and sick‐leave days during the past year were derived from the medical records and questionnaires. Information on other doctor visits because of menorrhagia and other causes was obtained from the questionnaire. Women's own costs included travel costs for health care services and sanitary pads. For pricing the hospital services, average Finnish prices of diagnosis related groups (DRG group) were used, and the costs of primary health services were based on Finnish standard cost information. 16 Unit costs of examinations other than those carried out in gynaecology outpatient clinics were obtained from the Social Insurance Institution. The productivity loss as a result of sick‐leave days was defined as the average daily gross wage of women in Finland (1999), including social security contributions (83€ per day). We also did a sensitivity analysis using a lower estimate of productivity loss (one‐third of average wage rate). The price of the decision aid was 10€. Given that the time horizon of the analysis was only 1 year, cost items were not discounted. Costs were analysed from the societal perspective and converted to the 1999 price level.

Statistical analysis

The target sample size of 180 women per group was calculated to give 80% power to detect 10% difference between study groups with an α‐error of 0.05 in the RAND‐36 dimension with the widest standard deviation, ‘emotional role functioning’. The population level of this dimension in Finland is 78 among women aged 35–54 years. 10

In all analyses, the intention to treat principle was used. In composite scales (instruments of HRQoL, anxiety, psychosomatic symptoms, inconvenience because of heavy bleeding), missing information on a single item was replaced with the mean of non‐missing item values if less than half of the items were missing. 17 Otherwise, missing data were excluded from the analyses. If only some of the data concerning the use of health services were missing, missing responses were interpreted to indicate no use.

Group differences were analysed by comparing means and proportions. Statistical significance was tested by the chi‐squared test, and Fisher's exact test for proportions, and Student's t‐test for means. The Mann–Whitney U‐test was used to compare medians of satisfaction with the outcome of treatment score. Two‐tailed tests, and a 0.05 critical value of statistical significance were used.

Results

The sample comprised 569 women: 363 in the randomized trial (184 in the intervention group, 179 in the control group) and 206 in the pre‐trial sample (Fig. 1).

A thorough comparison of the baseline characteristics of the participants in the three groups has been presented elsewhere. 6 The only statistically significant difference between the intervention and control group was that women in the former had fewer doctor visits for causes other than menorrhagia during the 12 months prior to randomization (3.01 vs. 3.79, P = 0.04). 6 In the pre‐trial group, the proportion of women perceiving their periods as very heavy was lower (54% vs. 64%, P = 0.04) than in the control group.

At the 1‐year follow‐up there was an overall positive change in several dimensions of RAND‐36, i.e. perceived health (VAS), and psychological and menstrual health outcomes, but not in sexual life (1, 2). The intervention group reported a greater increase in the dimension of emotional role functioning than the control group (12.6 vs. 1.9, P = 0.01). None of the changes in other dimensions of RAND‐36, in perceived health (VAS), anxiety, psychosomatic symptoms, sexuality, menstrual symptoms or satisfaction with the outcome of treatment differed between the intervention and control group (1, 2).

Table 1.

Health outcome scores at baseline and score change after 12 months

| RAND‐361 | Baseline values | Change at 12 months | p1 | p2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Change | SE | |||

| General health | ||||||

| Intervention | 66 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.23 | 0.7 | 0.07 |

| Control | 67 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 1.22 | – | 0.03 |

| Pre‐trial | 67 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 1.15 | 0.8 | 0.04 |

| Physical functioning | ||||||

| Intervention | 86 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 1.33 | 0.9 | 0.04 |

| Control | 85 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.32 | – | 0.1 |

| Pre‐trial | 87 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.25 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| Emotional well‐being | ||||||

| Intervention | 69 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 1.40 | 0.7 | 0.001 |

| Control | 69 | 1.5 | 5.3 | 1.39 | – | 0.000 |

| Pre‐trial | 67 | 1.5 | 6.3 | 1.30 | 0.6 | 0.000 |

| Social functioning | ||||||

| Intervention | 75 | 1.9 | 5.2 | 1.98 | 0.5 | 0.01 |

| Control | 74 | 1.8 | 7.1 | 1.96 | – | 0.000 |

| Pre‐trial | 73 | 1.8 | 6.7 | 1.84 | 0.9 | 0.000 |

| Energy | ||||||

| Intervention | 55 | 1.8 | 8.9 | 1.72 | 0.9 | 0.000 |

| Control | 55 | 1.8 | 8.8 | 1.71 | – | 0.000 |

| Pre‐trial | 53 | 1.7 | 9.1 | 1.60 | 0.9 | 0.000 |

| Pain | ||||||

| Intervention | 68 | 1.8 | 6.5 | 1.96 | 0.9 | 0.002 |

| Control | 69 | 1.8 | 6.2 | 1.95 | – | 0.001 |

| Pre‐trial | 68 | 1.7 | 9.5 | 1.89 | 0.2 | 0.000 |

| Role functioning/physical | ||||||

| Intervention | 65 | 3.0 | 9.2 | 3.41 | 0.5 | 0.007 |

| Control | 67 | 3.0 | 6.3 | 3.38 | – | 0.07 |

| Pre‐trial | 61 | 2.9 | 16.5 | 3.10 | 0.025 | 0.000 |

| Role functioning/emotional | ||||||

| Intervention | 64 | 3.1 | 12.6 | 3.13 | 0.01 | 0.000 |

| Control | 72 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 3.09 | – | 0.5 |

| Pre‐trial | 63 | 2.9 | 13.1 | 2.85 | 0.007 | 0.000 |

| Perceived health, VAS (scale 0–100) | ||||||

| Intervention | 73 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 1.38 | 0.6 | 0.09 |

| Control | 73 | 1.4 | 3.6 | 1.36 | – | 0.003 |

| Pre‐trial | 72 | 1.3 | 5.2 | 1.29 | 0.4 | 0.000 |

Values are given for those who gave 12‐month follow‐up information (n = 493).

1Scale 1 – 100 in each dimension, higher scores indicating better health; positive change means improvement in health status.

p1, significance of change between groups, control group as reference, t‐test; p2, significance of change within a group, t‐test.

Table 2.

Psychological and menstrual health outcome scores at baseline and score change after 12 months

| Baseline values | Change at 12 months | p1 | p2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Change | SE | |||

| Anxiety (scale 20–80)1 | ||||||

| Intervention | 36.0 | 0.85 | 2.0 | 0.78 | 0.4 | 0.012 |

| Control | 35.8 | 0.85 | 1.0 | 0.78 | – | 0.199 |

| Pre‐trial | 36.4 | 0.80 | 2.0 | 0.74 | 0.4 | 0.007 |

| Psychosomatic symptoms (scale 18–72)1 | ||||||

| Intervention | 31.8 | 0.59 | 3.4 | 0.53 | 0.5 | 0.000 |

| Control | 32.1 | 0.58 | 3.8 | 0.53 | – | 0.000 |

| Pre‐trial | 32.4 | 0.55 | 3.6 | 0.50 | 0.8 | 0.000 |

| Menstrual symptoms 1 | ||||||

| Inconvenience due to heavy bleeding (scale 5–25) | ||||||

| Intervention | 19.1 | 0.38 | 10.4 | 0.58 | 0.9 | 0.000 |

| Control | 19.5 | 0.37 | 10.5 | 0.57 | – | 0.000 |

| Pre‐trial | 19.1 | 0.35 | 10.5 | 0.53 | 1.0 | 0.000 |

| Menstrual pain (scale 0–12) | ||||||

| Intervention | 4.8 | 0.29 | 4.7 | 0.29 | 0.8 | 0.000 |

| Control | 4.7 | 0.29 | 4.6 | 0.29 | – | 0.000 |

| Pre‐trial | 4.3 | 0.27 | 4.2 | 0.27 | 0.4 | 0.000 |

| Sexuality 2 | ||||||

| Sexual satisfaction (scale 5–35)3 | ||||||

| Intervention | 23.7 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.4 | 0.487 |

| Control | 24.2 | 0.42 | −0.14 | 0.36 | – | 0.688 |

| Pre‐trial | 23.6 | 0.39 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 0.6 | 0.752 |

| Sexual problems (scale 2–14)1 | ||||||

| Intervention | 4.70 | 0.20 | −0.23 | 0.18 | 0.8 | 0.224 |

| Control | 4.33 | 0.20 | −0.15 | 0.18 | – | 0.444 |

| Pre‐trial | 4.35 | 0.19 | −0.22 | 0.17 | 0.8 | 0.148 |

| Partner satisfaction (scale 3–21)3 | ||||||

| Intervention | 17.1 | 0.27 | −0.08 | 0.18 | 0.9 | 0.659 |

| Control | 17.1 | 0.27 | −0.13 | 0.18 | – | 0.436 |

| Pre‐trial | 17.0 | 0.25 | −0.48 | 0.17 | 0.2 | 0.009 |

| Satisfaction with outcome of treatment | ||||||

| VAS (scale 0–100)3 median (Q1, Q3) | ||||||

| Intervention | 94 | (75, 100) | 0.9 | – | ||

| Control | 95 | (75, 100) | – | – | ||

| Pre‐trial | 92 | (70, 100) | 0.7 | – | ||

Values are given for those who gave 12‐month follow‐up information (n = 493).

Positive change meaning improvement of symptoms, greater satisfaction.

1Higher score indicating more symptoms/problems.

2Those with partner (n = 450).

3Higher score indicating higher satisfaction. Q1 and Q3 are quartiles.

p1, significance of change between groups, control group as reference, t‐test; p2, significance of change within a group, t‐test.

Table 3 shows the use of health care services by group during the 12‐month study period. In the intervention compared with the control group there was a statistically insignificant tendency towards a lower rate of diagnostic procedures (55 vs. 89 procedures, mean 0.35 and 0.56, P = 0.07 t‐test for mean), lower rate of uterus saving surgery (16 vs. 26 procedures, 0.10 and 0.16, P = 0.08) and higher rate of medical treatment episodes (51 vs. 34 episodes, 0.33 and 0.21, P = 0.06).

Table 3.

Use of health care services and medication by group

| Resource use | Intervention group (n = 156) | Control group (n = 159) | Pre‐trial group (n = 178) | P‐values1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C vs. I | C vs. PT | ||||

| Number of diagnostic procedures | |||||

| D&C | 28 (0.18) | 41 (0.26) | 43 (0.24) | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Hysteroscopy | 14 (0.09) | 25 (0.16) | 31 (0.17) | 0.09 | 0.7 |

| Hysteroscopy and D&C, concomitant | 12 (0.08) | 21 (0.13) | 23 (0.13) | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Colposcopy | 1 (0.01) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.01) | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Diagnostic laparoscopy | 0 (0) | 2 (0.01) | 0 (0) | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Sum of the procedures above | 55 (0.35) | 89 (0.56) | 98 (0.55) | 0.07 | 0.9 |

| Number of treatment procedures and control visits | |||||

| Outpatient clinic visits without any procedure | 327 (2.10) | 320 (2.01) | 365 (2.05) | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| Hysterectomy (%) Chi sq‐test | 79 (0.51) | 77 (0.48) | 95 (0.53) | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| Sterilization (%) Fischer's exact test | 2 (0.01) | 2 (0.01) | 1 (0.01) | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Thermal ablation | 8 (0.05) | 11 (0.07) | 3 (0.02) | 0.4 | 0.02 |

| Resection of endometrium2 | 7 (0.05) | 14 (0.09) | 5 (0.03) | 0.1 | 0.02 |

| Myomectomy (via laparoscopy or laparotomy) | 1 (0.01) | 1 (0.01) | 2 (0.01) | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| Sum of three procedures above | 16 (0.10) | 26 (0.16) | 10 (0.06) | 0.08 | 0.002 |

| Re‐admissions due to complication | 5 (0.03) | 2 (0.01) | 3 (0.02) | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| Other treatments | |||||

| Medical treatment, number of episodes | 51 (0.33) | 34 (0.21) | 44 (0.25) | 0.06 | 0.6 |

| Hormonal IUS (has or had during follow‐up) | 21 (0.13) | 24 (0.15) | 18 (0.10) | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| Number of doctor visits | |||||

| Due to menorrhagia3 | 303 (1.94) | 316 (1.99) | 316 (1.78) | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| Due to other causes4 | 520 (3.33) | 478 (3.01) | 566 (3.18) | 0.5 | 0.7 |

Values are given as numbers (means) and t‐test values for means of women who gave 12‐month follow‐up information (n = 493).

I, intervention group; C, control group; PT, pre‐trial group; D&C, dilatation and curettage; hormonal IUS, hormonal intrauterine system.

1 T‐test for difference in means between groups, control group as reference.

2Includes hysteroscopic resection or destruction of endometrium, polyp of fibroid removal.

3To general practitioner in health centre and private gynaecologist.

4To general practitioner in health centre and private physician.

Table 4 shows data on direct costs and productivity losses because of menorrhagia during the 1‐year follow‐up. There were no differences in direct menorrhagia treatment costs between the intervention and control group (1952€ vs. 2042€, respectively, P = 0.5). The productivity loss was slightly lower in the intervention group (807€ vs. 1052€, P = 0.08) but there was no difference in the total estimated costs (2760€ vs. 3094€, P = 0.1) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Total costs (€) per woman due to menorrhagia by group over 12‐month follow‐up

| Cost component | Intervention group (n = 156) | Control group (n = 159) | Pre‐trial group (n = 178) | P‐values1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C vs. I | C vs. PT | ||||

| Treatment and controls in gynaecology clinics2 | |||||

| Surgery/procedure | 1448 (81) | 1547 (81) | 1467 (77) | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Outpatient clinic visits | 240 (12) | 237 (12) | 235 (11) | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Medical treatments (hormonal IUS + oral medications) | 41 (4.7) | 38 (4.7) | 31 (4.4) | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| Doctor visits elsewhere than gynaecology outpatient clinics due to menorrhagia3 | 81 (6.5) | 84 (6.4) | 72 (6.1) | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| Tests | 52 (3.9) | 46 (3.9) | 36 (3.7) | 0.3 | 0.08 |

| Women's own costs: travel, sanitary pads | 81 (6.8) | 91 (6.7) | 72 (6.4) | 0.3 | 0.05 |

| Intervention (information booklet) | 10 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Costs (sum of above mentioned) | 1952 (86) | 2042 (86) | 1914 (81) | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Productivity loss due to menorrhagia4 | 807 (99) | 1052 (98) | 825 (93) | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Total costs due to menorrhagia | 2760 (162) | 3094 (161) | 2739 (152) | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Values are given as mean (SE) of women who gave 12‐month follow‐up information (n = 493).

I, intervention group; C, control group; PT, pre‐trial group.

1 T‐test for difference between groups, control group as reference.

2Includes diagnostic tests and procedures.

3General practitioner in health centre, private physician and private gynaecologist.

483€ per day, 100% gross wage. If unemployed or retired, productivity loss is 0.

Table 5 shows data on health care costs for causes other than menorrhagia, with no differences between the intervention and control group. Using a lower estimate of productivity loss did not change the cost disparities between the groups (Table 6).

Table 5.

Total costs (€) per woman due to causes other than menorrhagia by study group over 12‐month follow‐up (n = 493)

| Cost component | Intervention group (n = 156) | Control group (n = 159) | Pre‐trial group (n = 178) | P‐values1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C vs. I | C vs. PT | ||||

| Not menorrhagia‐related causes | |||||

| Outpatient visits | 178 (48) | 184 (47) | 97 (45) | 0.9 | 0.2 |

| Inpatient | 385 (265) | 855 (263)2 | 135 (248) | 0.2 | 0.05 |

| Doctor visits due to other causes than menorrhagia2 | 120 (12) | 107 (12) | 114 (11) | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Women's own costs | 115 (18) | 98 (17) | 109 (17) | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Costs (sum of above mentioned) | 798 (285) | 1244 (282) | 455 (266) | 0.3 | 0.04 |

| Productivity loss due to other causes than menorrhagia3,4 | 1049 (199) | 826 (197) | 386 (187) | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Total costs due to causes other than menorrhagia | 1847 (405) | 2070 (401) | 841 (379) | 0.7 | 0.03 |

Values are given as means (SE).

I, intervention group; C, control group; PT, pre‐trial group.

1 T‐test for difference between groups, control group as reference.

2General practitioner in health centre and private physician.

3Including two women with exceptionally long inpatient spells, 150 and 60 days, due to causes other than menorrhagia.

4If unemployed or retired, productivity loss is 0.

Table 6.

Total costs of health care per woman at 12‐month follow‐up for those providing information (n = 493)

| Cost component | Intervention group (n = 156) | Control group (n = 159) | Pre‐trial group (n = 178) | P‐values1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C vs. I | C vs. PT | ||||

| Costs of health care | |||||

| Due to menorrhagia | 1871 (86) | 1951 (85) | 1842 (81) | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Due to other causes than menorrhagia | 683 (282) | 1146 (280) | 346 (264) | 0.2 | 0.04 |

| Subtotal (sum of above) | 2554 (295) | 3097 (292) | 2188 (276) | 0.2 | 0.02 |

| Women's own direct costs | 196 (19) | 189 (19) | 182 (18) | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Standard estimate of productivity loss2 | |||||

| Due to menorrhagia | 807 (99) | 1052 (98) | 825 (93) | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Due to other causes than menorrhagia | 1049 (199) | 826 (197) | 386 (187) | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Standard estimate of productivity loss2 (sum of above) | 1856 (220) | 1879 (218) | 1210 (206) | 0.9 | 0.03 |

| Lower estimate of productivity loss3 | 619 (73) | 626 (72) | 403 (69) | 0.9 | 0.03 |

| Total (health care and productivity loss) | |||||

| Standard estimate | 4607 (431) | 5164 (427) | 3580 (403) | 0.4 | 0.007 |

| Low estimate | 3369 (332) | 3912 (329) | 2773 (311) | 0.2 | 0.01 |

I, intervention group, C, control group, PT, pre‐trial group.

1 T‐test for difference between groups, control group as reference.

2If unemployed or retired, productivity loss is 0.

3Third of average wage rate.

In the pre‐trial group compared with the control group, there was a greater increase in the dimensions of physical role functioning and emotional role functioning of the RAND‐36 (P = 0.03 and 0.007, respectively), but no difference in any other health outcomes (1, 2). The pre‐trial group also had a significantly lower rate of uterus saving surgery (26 vs. 10 procedures, P = 0.002 t‐test for mean) (Table 3), but no difference in costs because of menorrhagia treatment (Table 4). The costs due to hospital inpatient stays for causes other than menorrhagia were lower in the pre‐trial than the control group (135€ vs. 855€, respectively, P = 0.05) (Table 5), helping to produce a significant difference also in total costs because of causes other than menorrhagia (841 vs. 2070, P = 0.03). Excluding one participant with severe mental disease and another with multiple endocrinological diseases and asthma eliminated the differences.

Discussion

In spite of no marked difference in health outcomes between the study groups at the 1‐year follow‐up, there was an overall improvement in health outcomes among all these women with menorrhagia. The only exception was sexual life, which showed no improvement. The decision aid for menorrhagia did not affect health care costs, despite some differences in treatments courses. 6 The overall improvement in health outcomes, but with no marked difference between the study groups, is in line with the previous results. 3

Sexual life was not used as an outcome measure in any of the 30‐plus trials on decision aids included in the Cochrane review. 2 Some of those studies focused on treatment decisions that affect sexual life, e.g. prostate cancer and breast cancer treatments. In a randomized trial comparing hysterectomy and hormonal intrauterine system in the treatment of menorrhagia, there was no difference in sexual life between the study groups at the 1‐year follow‐up. 18 One possible explanation is that a good partnership is more important for sexual life than gynaecological health.

In this study, the intervention group tended towards a lower rate of treatment and investigation episodes during the 1‐year follow‐up compared with the control group. This accords with our earlier report, which found a significant difference in the proportion of end‐point treatments between the intervention and control group. 6

In Kennedy's et al. study, 3 the information pack plus interview resulted in reduced costs, but not the information pack alone. In two earlier studies based on other medical conditions, the higher costs occurring in the intervention group resulted from an expensive interactive multimedia decision aid. 4 , 5 In the present study, the cost of the low‐tech decision aid was insignificant compared with the other cost components of treatment. In general, the decrease of treatment costs is not considered as the main aim of a decision aid, but improved patients’ activity and participation when treatment decisions are made.

All women had menorrhagia as the main actual health problem. Use of two information sources, medical records and a questionnaire, reduced the potential information gap from one follow‐up source. Information on operative treatment, inpatient stays and outpatient visits was obtained from medical records. In general, the two sources provided similar information. However, five women who had hysterectomy, and four who had minor surgery, failed to report the operation in the questionnaires. The response rate was high (87% in questionnaire) and validated health outcome scores were used. The pre‐trial group enabled some time trend evaluation during a period of changes in clinical practice in the treatment of menorrhagia.

It is possible that women whose actual symptom(s) was other than heavy menstruation decided not to respond. The respondents could easily notice in the baseline questionnaire that it focused on heavy menstruation, because the term heavy periods/heavy menstrual bleeding was used (instead of menstrual complaint, for example). Some women who returned the questionnaire but were not willing to participate gave this as the reason. No other signs of self‐exclusion were detected. The study population is highly representative of Finnish women aged 35 years or over whose actual health problem is heavy menstruation.

The fact, that those women who gave questionnaire follow‐up information, were healthier than non‐respondents, may somewhat overestimate the impact of menorrhagia treatment in terms of health outcomes. It is, however, unlikely that this influences on the results of the impact of the decision aid.

A possible carry‐over effect in information flow from the intervention group may have altered the physicians’ practice of negotiating with their patients. 6 Such a bias would have reduced any observed differences in outcome between the intervention and control group, so our conclusions can be considered conservative.

Outcomes of menorrhagia treatment in terms of quality of life appear to be very similar when hysterectomy, endometrial destruction 19 or hormonal intrauterine device 18 have been compared. We have shown earlier that a decision aid can influence treatment decisions. 6 Better informed women, however, might have experienced other aspects of their treatment decision‐making process that could not be captured in a questionnaire and thus are not reflected in health outcomes of treatment.

Improving the women's participation in treatment decision‐making by providing them with a decision aid containing additional information on their actual health problem – menorrhagia – had some impact on treatment courses. However, the decision aid did not increase the use of health services or treatment costs, or had it impact on health outcomes, or on satisfaction with outcome of treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the women who gave their time to take part in the survey. We also thank the staff of the gynaecologic clinics in the study hospitals: Hyvinkää, Jorvi, Kätilöopisto, Lohja and Peijas Hospitals, Kanta‐Häme, Keski‐Suomi, Kymenlaakso, Pohjois‐Karjala and Seinäjoki Central Hospitals, and the University Teaching Hospitals of Kuopio, Oulu, Tampere and Turku. Thanks to Raimo Kekkonen and Leena Suonoja for their valuable and critical comments, and to Iiris Juvonen and Eija Teitto for DRG grouping.

This study was supported by STAKES, the National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health, and Public Health Doctoral Programmes of Helsinki and Tampere universities.

References

- 1. Molenaar S, Sprangers MAG, Postma‐Schuit FCE, Rutgers EJT, Noorlander J, Hendriks J, et al. Feasibility and effects of decision aids. Medical Decision Making, 2000; 20: 112–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2003; 2: CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kennedy ADM, Sculpher MJ, Coulter A et al. Effects of decision aids for menorrhagia on treatment choices, health outcomes, and costs. JAMA, 2002; 288: 2701–2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murray E, Davis H, Tai SS, Coulter A, Gray A, Haines A. Randomised controlled trial of an interactive multimedia decision aid on hormone replacement therapy in primary care. British Medical Journal, 2001; 323: 490–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murray E, Davis H, Tai SS, Coulter A, Gray A, Haines A. Randomised controlled trial of an interactive multimedia decision aid on benign prostatic hypertrophy in primary care. British Medical Journal, 2001; 323: 493–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vuorma S, Teperi J, Aalto A‐M, Hurskainen R, Kujansuu E, Rissanen P. Impact of patient information booklet on treatment decision – a randomized trial among women with heavy menstruation. Health Expectation, 2003; 6: 290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Luukkainen T, Lähteenmäki P, Toivonen J. Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device. Annals of Medicine, 1990; 22: 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scholten PC. Levonorgestrel IUD. Clinical Performance and Impact on Menstruation. Utrecht, the Netherlands: University of Utrecht, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Effective Health Care . The management of menorrhagia. Effective Health Care, 1995; Bulletin No. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aalto A‐M, Aro AR, Teperi J. RAND‐36 terveyteen liittyvän elämänlaadun mittarina [in Finnish: RAND‐36 as a measure of Health‐Related Quality of Life]. Saarijärvi: STAKES, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36‐item Health Survey 1.0. Health Economics, 1993; 2: 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13. METELI . Occupational status, working environment, and morbidity among employees of metal industry factories [in Finnish: Ammattiasema, työolot ja sairastavuus metalliteollisuuden henkilöstöryhmissä]. Jyväskylä: Gummerus, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wiklund I, Karlberg J, Lindgren R, Sandin K, Mattsson L. A Swedish version of the Women's Health Questionnaire. A measure of postmenopausal complaints. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 1993; 72: 648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vuorma S, Teperi J, Hurskainen R, Aalto A‐M, Rissanen P, Kujansuu E. Correlates of women's preferences for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. Patient Education and Counseling, 2003; 92: 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heikkinen K, Hujanen T, Rusama H. Guidelines for Health Care Unit Costs in Finland in 2000 [in Finnish: Terveydenhuollon yksikkökustannukset Suomessa vuonna 2000]. Helsinki: STAKES, 2001, 72 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fairclough DL, Cella DF. Functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT‐G): non‐response rate to individual questions. Quality of Life Research, 1996; 5: 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hurskainen R, Teperi J, Rissanen P, et al. Quality of life and cost‐effectiveness of levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system versus hysterectomy for treatment of menorrhagia: a randomised trial. Lancet, 2001; 357: 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lethaby A, Shepperd S, Cooke I, Farquhar C. Endometrial resection and ablation versus hysterectomy for heavy menstrual bleeding (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2003; CD000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]