Abstract

Involving the public in decision‐making has become a bureaucratic pre‐occupation for every health agency in the UK. In this paper we offer an innovative approach for local participation in health decision‐making through the development of a ‘grounded’ citizens’ jury. We describe the process of one such jury commissioned by a Primary Care Group in the north‐west of England, which was located in an area suffering intractable health inequalities. Twelve local people aged between 17 and 70 were recruited to come together for a week to hear evidence, ask questions and debate what they felt would improve the health and well‐being of people living in the area. The jury process acted effectively as a grass‐roots health needs assessment and amongst other outcomes, resulted in the setting up of a community health centre run by a board consisting of members of the community (including two jurors) together with local agencies. The methodology described here contrasts with that practiced by what we term ‘the consultation industry’, which is primarily interested in the use of fixed models to generate the public view as a standardized output, a product, developed to serve the needs of an established policy process, with little interest in effecting change. We outline four principles underpinning our approach: deliberation, integration, sustainability and accountability. We argue that citizens’ juries and other consultation initiatives need to be reclaimed from that which merely serves the policy process and become ‘grounded’, a tool for activism, in which local people are agents in the development of policies affecting their lives.

Keywords: citizens' juries, health activism, health inequalities, participation

Introduction

Over the last 5 years the issue of public consultation has become increasingly embedded within the Government's modernization agenda. All public authorities in England are now charged with consulting their publics in drawing up new service plans and strategies, and, in reviewing these services, to ensure closer alignment between provision and need. The 1999 Green Paper, Our Healthier Nation, recognized that ‘the patient's voice does not sufficiently influence the provision of services’, 1 and the 2000 NHS Plan detailed proposals aimed to redress this failing. 2 These included the replacement of Community Health Councils with what are now known as Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) Forums within primary care and hospitals trusts, along with a new Independent Complaints Advocacy Service in each locality; the setting up of a Patient Advice and Liaison Service within NHS Trusts; annual patient surveys to be contained in a Patient Prospectus; provision of financial rewards linked to results of annual patient surveys; local resident advisory forums set up within health authority areas to assist policy development, and increased lay membership of a range of NHS decision‐making bodies.

In 2001, legislation was passed in which all trusts and health authorities were required to make arrangements to involve and consult patients and the public in service planning, operation, and in the development of proposals for changes. 3 In an effort to increase democratic accountability, local authority Overview and Scrutiny Committees were enabled to scrutinize local health services and be consulted on proposed changes. 4 There has been much discussion on the detailed workings of these proposals over the last 2 years. 5 Further proposals were made for developing a national Commission for PPI (finally established in December 2002) and the appointment of a Director for PPI at the Department of Health. All of these changes have been introduced within health agencies, yet other policy developments within the areas of social exclusion and health inequalities, urban regeneration, and modernizing local government, have simultaneously impacted on health services. For example, the establishment of Local Strategic Partnerships has required direct input from local health services and they have been charged with a duty to consult with the public. 6

Taking all these developments into account, there is no doubt that a version of ‘the public’ has now been officially inserted into local health decision‐making. However, even the Government's Shifting the Balance of Power (2002) document stated that ‘…structural change in itself does not necessarily make people work differently….’ 7 We wonder how much any of it will make a real difference to the millions of people living in poverty in the UK who are traditionally unheard, ignored or silenced. In particular, we are concerned to observe the reliance of health and social care agencies on a sanitized version of ‘the public view’, produced through engagement with a ‘consultation industry’ that has established itself over the last 10 years. 8 , 9 We have evidenced this development as researchers, where we are repeatedly invited to submit proposals for consultation projects knowing what is being sought is ‘the public view at a competitive price’, rather than critical engagement and identification of complexities.

In this context, we suggest that our work within a highly marginalized community is a possible alternative for engaging with people in a meaningful way that does not require the high profile changing of structures, abolishing of established organizations, passing of new legislation, or appointments to centralized bureaucracies (given the paradoxical job of increasing local involvement). Our experience with citizens’ juries in Burnley goes some way towards exploring possibilities for action research and grass‐roots activism in engaging with statutory services.

Citizens’ juries are being used as a public consultation tool by state agencies; 10 , 11 more than 100 have now been held in the UK, on a wide range of topics such as women's issues, local ecology, transport needs, regeneration, community responses to drug misuse, and the needs of older people. Arguably the process of a citizens’ jury is familiar in the English system of governance in that it loosely resembles legal juries. Typically 12–16 citizens are brought together over a 4–5‐day period with the aim of reaching a ‘verdict’ on a particular policy‐related issue. The jury hears testimonies from witnesses and is given time for deliberation before reaching its decision. Facilitators transcribe and report on the proceedings and the jury's recommendations. In contrast with legal juries however, this report is then presented to the sponsors or commissioners for consideration. Often the commissioning agency is committed to responding within a given period and may meet the jury to explain what action will follow, but is not necessarily committed to acting on the decision(s) in full. This model of the citizens’ jury was promoted by the Institute for Public Policy Research on the basis of research into similar models in the US and Germany. 12 The major weakness of the design is that the process simply extracts ‘the public view’ without any in‐built mechanism for follow‐up, scrutiny or accountability.

Our starting point is that participation in decision‐making is a human right and without it, solutions to intractable social issues cannot be developed or sustained. 13 Very few consultation projects initiated by state agencies in response to recent policy requirements have demonstrated meaningful participation or been shown to have effected change in policy or practice. In our experience of researching public involvement over the last 10 years, consultation activities can be located along a spectrum of participation from ‘incidental’ to ‘grounded’. Those that we conceptualize as ‘incidental’ generally occur because agencies are required to do something, with the consultation exercise being perceived as not particularly relevant to the agency's core work – as one senior officer in a PCT told us, ‘men in suits are doing these for other men in suits, and we all know it’. The exercise is carried out in the interests of the agency rather than the public; the issue under discussion is of relevance to the agency rather than the public, and there is little involvement from the public in the early process of developing the consultation or later responses to it. Some notional effort is made to consult the public but with little expectation that anything substantial will change as a result. Lack of commitment, even resistance to more collaborative means of decision‐making is a feature of both hierarchical organizations and representative models of democracy (managers, officers and professionals; councillors and MPs).

By ‘grounded’ consultation we mean that the issue under discussion arises from within communities; that there is a high level of commitment to the process and outcomes from the commissioners; the problem or question for debate is framed and developed collaboratively; recommendations are context‐specific and developed within the framework of existing community assets and expertise, and most importantly, opportunities are provided for longer term involvement of local people, retaining the skills developed through the process.

Whilst there are many other innovative and interesting methodologies for increasing dialogue and deliberation (such as Consensus Conferences, Health Panels and Citizen Foresight initiatives) we used the citizens’ jury methodology first to build up a body of evidence through the testimonials of jurors, witnesses and other members of the community, second to resolve a specific long‐standing problem regarding local service provision, and third to open up debate about what people living in that community would prioritize for change. As action researchers, we were keen to see whether the jury process could hold service providers and policymakers accountable to the community, and to explore whether the process could be used as a tool for health activism.

The South West Burnley citizens’ jury on health and social care

Burnley is a post‐industrial town situated in the north‐west of England. Particular parts of the town have high levels of social deprivation and social exclusion. South West Burnley (SWB) has a population of about 18 000 and is heavily enclosed within a triangle of three major roads/highways. For this reason the area has a distinctive character although it is only 3 km from the town centre. It contains different communities with varying lifestyles and concerns, and has a wide variation in housing (social housing; privately owned or rented terraces; semi‐detached and some detached houses). There is a strong sense of community in some parts of the area while other parts are fragmented and have a much more transitory population with no commitment to each other or the area.* At the time of our original research SWB had a very active community sector with publicly funded community organizations. Most significantly, two of the electoral wards come into the worst 5% nationally in terms of economic and social deprivation. 14 The social problems that have concerned people in the area for many years are: †

-

•

poverty and low pay;

-

•

poor housing and proliferation of empty properties;

-

•

high levels of death, illness and disability;

-

•

increasing alcohol abuse by children and teenagers;

-

•

drug abuse and dealing;

-

•

high crime levels, particularly drug‐related burglaries;

-

•

poor access to health and social care services;

-

•

low literacy levels;

-

•

lack of access to good quality food;

-

•

teenage pregnancies;

-

•

lack of adequate adult supervision of children;

-

•

high volume of fast‐moving commercial traffic;

-

•

road accidents affecting children in particular;

-

•

life punctuated by a constant stream of random occurrences – little control over life events;

-

•

fear/anxiety over what may happen next;

-

•

fear and mistrust of others in the neighbourhood.

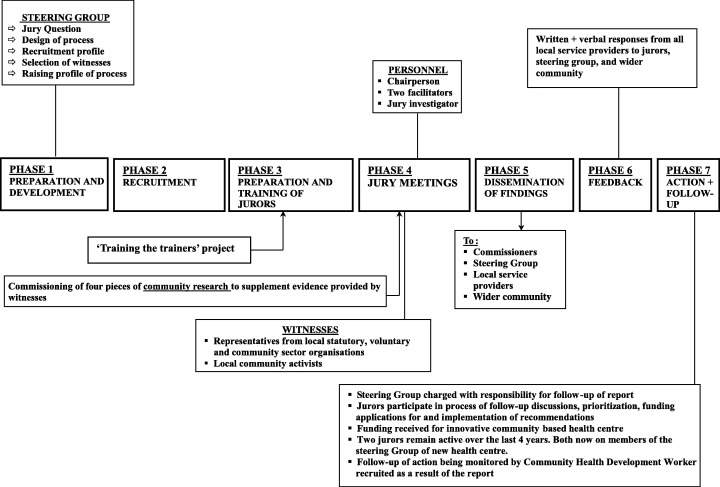

In 1999, the then Burnley Primary Care Group, working through a community‐led Health and Social Care Group, commissioned a citizens’ jury, as an exercise in locally based health needs assessment. This was highly significant as for more than a decade local residents and community groups had campaigned for health and social care services to be located in their area. There were differing opinions in the community as to what services were needed – whether primary care or a more diverse and community‐based nurse‐led practice. The PCG wanted this long running controversy resolved through the jury process as health agencies had commissioned research into needs many times over the previous decade with no resulting change. 15 , ‡ In addition, findings from a previous community‐based citizens’ jury in the area highlighted serious concerns about poor access to services and agency support for the local population. 9 , § All agencies agreed that this consultation would have to be the final one, and there was a high level of commitment from commissioners. Critically, the process was personally and actively endorsed by the PCG chief executive; ‘where such champions exist and where they can create sufficient momentum within organizations, the processes of invited participation that they help instigate can make a real difference’. 16 The different phases of the process are outlined in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The process of the SWB grounded citizens’ jury project.

Preparation and development

The establishment of the jury steering group was key to the success and legitimacy of this project. Burnley Primary Care Group had been active partners of a Health and Social Care Group set up by community organizations a few years previously in a desperate attempt to draw attention to people's lived experience of health inequalities. This group agreed to oversee the project and nominated representatives from across the statutory, voluntary and community sectors to act as the jury steering group. The steering group took all decisions relating to the research process. In this way, the process was collaborative, actively led by local community organizations, and grounded at every point in local knowledge and practice. As its first task, the Health and Social Care Group set the central question for the jury to consider simply as: ‘What would improve the health and well‐being of residents of SWB?’

Key characteristics of this citizens’ jury:

-

•

Commissioned to address existing (and increasing) inequalities in health within a defined geographical community;

-

•

Underlying premise was that local people's expertise was the most important asset;

-

•

Deliberately convened with a broad agenda to allow jury members to articulate their needs and responses to health inequalities;

-

•

Ultimate aim was to seek action – jury process was to contribute directly to changes in service planning content and mode of provision;

-

•

Underpinned by development work in the community, and capacity building between statutory, voluntary and community sectors.

Recruitment of jurors

The legitimacy of the jury process further hinged on the formulation of a transparent and locally recognized recruitment method. We rejected the more traditional means of jury selection, such as random sampling through the electoral roll or the telephone book, as this would systematically exclude many people. Presented with local census data, the steering group spent many hours debating and deciding on what the recruitment profile ought to be, and how the census data needed to be modified using their knowledge and expertise of the area. The steering group decided whom they wanted to hear from and it is this fact that gives the jury its legitimacy, not some notional claim of representativeness.

A professional recruiter with previous working knowledge of the area, spent many weeks talking with people on the estates, at post offices, supermarkets, outside schools, and at bus stops in order to ‘find’ the jury to match the profile below (Table 1) which was developed by the steering group.

Table 1.

Recruitment profile for SWB citizens’ jury

| Age | Gender | Economic status | Children under 16 | Type of housing | Health‐related issue | Access to car |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | M | Unemployed | No children | Council | No car | |

| 21 | M | Unemployed | No children | Council | Carer | No car |

| 23 | F | Unemployed | Four children/single parent | Private rented | No car | |

| 27 | M | Unemployed | None living with him | Private rented | No car | |

| 34 | F | Unemployed | One/single Parent | Council | Carer | No car |

| 38 | M | Working | Two children | Owner occupier | Has car | |

| 43 | F | Working | None under 16 | Council | Has car | |

| 43 | M | Unemployed | None under 16 | Council | Has disability | Has car |

| 43 | F | Unemployed | Some grown up, three under 16 | Council | Carer | No car |

| 58 | F | Unemployed | None under 16 | Owner occupier | Has disability | Has car |

| 69 | F | Retired | None under 16 | Sheltered housing | No car | |

| 70 | M | Retired | None under 16 | Owner occupier | Carer | Has car |

While making no claim to representativeness in the abstract, we were keen to ensure the jury was made up of a diverse enough group of people to reflect the needs and interests of the wider community. All jurors were instructed at the outset that they were not there as representatives of their communities but merely as individuals who lived in the area and who, by that fact alone, had a legitimate right to be part of a deliberative process relating to the health of their community. Clearly each juror drew on their personal experience in more complex ways than simply as ‘a carer’, ‘a single parent mother of five’, or ‘a low paid worker’ but such experiences were crucial to the jury's deliberations.

Considering some of the challenges they had to meet and overcome to participate in the process, this group showed huge commitment to each other and to their community. Two jurors had disabling conditions which kept them in severe pain throughout the week (they insisted on continuing with the work); six jurors had difficulties with reading and writing to various degrees, two of whom were dyslexic; four were full‐time carers, while two were so anxious about relatives they had to go home during breaks to check on them. Jurors, chairperson and facilitators all worked together to support members with difficulties throughout the week with a remarkable degree of success.

Preparation and training with jurors

Once recruited, members attended two preparatory evening sessions at the community centre where the jury sessions would be held. Clearly a jury is a ‘false’ group of people of differing ages, backgrounds and abilities, having little connection to each other. Establishing a supportive emotional dynamic was crucially important for a free and open exchange of ideas to take place. 17 The sessions were designed to establish trust, develop a common sense of purpose, familiarize jurors with the process, create a safe space for talk, develop shared ownership of the jury, and make the experience as enjoyable as possible. We wanted people to feel they could talk:

I felt really comfortable. I'm always down on myself. I think look at me, 23 sat at home with 4 kids…I didn't get judged at all…up here I felt proper easy. I could tell them anything. Half of what I said in them rooms I haven't even talked to me mother about. (Juror, follow‐up interview)

When I first went in I thought I'm not going to talk to these people, but once I started talking it was ok. (Juror, follow‐up interview)

An important element of these sessions was also to give the jury the opportunity to accept and work with us as researchers. We knew from our previous local work that there was immense mistrust of outsiders in general, and service providers in particular. Initially some members wondered if we might be ‘native gazing’ out of curiosity. We spent a long time answering questions about our past, our motives, our interest in their community, and what we were getting out of the process as individuals. There were also many questions about who was funding the project and why. Many of the jurors later revealed that they would not have committed so much time and energy to the process had we not answered their questions so openly on that first night.

As part of the preparation, we worked with a locally respected community worker and four members of a previous jury held in the area 2 years before to develop a training session on the practicalities of being a juror. ¶ Using role play and humour, jurors were introduced and supported to learn about the processes of small group discussion, group decision‐making, the role of facilitators, their own place and function in the group and the process of taking evidence from witnesses. It was crucial at this point to demystify the process as much as possible and to encourage critical enquiry without deference to the perceived power or authority of ‘expert’ witnesses.

Jury sessions

Over 5 days, the jury heard evidence from a community development worker, a health policy advisor, a health visitor, a nurse practitioner, two GPs, a social worker, four youth and community workers, a family support worker, mental health professionals and activists, a community arts development worker, and several local activists and volunteers. Almost all the witnesses worked or lived in the area. In order to focus the proceedings around the jury's own expertise, we also held two closed sessions to enable members to identify what they saw as the main problems and possible solutions in their community.

As well as receiving oral and written evidence from witnesses, we commissioned four pieces of research for the jury. First, a mapping exercise of all community, voluntary and statutory sector health and social care provision in the area. This directory was left with community workers once the jury ended and was felt to be a useful resource for local groups. Secondly, children from a local primary school were consulted on what they felt made them healthy, what made them unhealthy, and what would make life better for them. Thirdly, a video was commissioned of discussions with older children on their sense of health and well‐being and their aspirations about these. Fourthly, a discussion was held with a young women's group from the estates, on issues they saw affecting their health. These reports were presented as evidence by different witnesses and provided invaluable insight into the perspectives of local children and young people whose voices might otherwise not have been heard directly by jurors. Prominent recommendations were made on the basis of this evidence and the ensuing discussions.

A more relaxed session with a community arts worker was scheduled in order to help members find ways to draw on their own expertise, and for the validation of local knowledges. The jury saw video clips of successful community arts projects held in other communities where there were tough social problems, and an exercise in creative writing helped to bring out members’aspirations for their community, rather than getting too focused on, for example, particular problems of NHS service provision.

Throughout the sessions there were opportunities for discussions in pairs, in rotating small groups and male/female groups, depending on the topic and the dynamic of the group at the time. As well as having two facilitators and a chairperson, jurors also had a jury investigator present at all times whose role was to pursue answers to questions raised as a result of their discussions. The investigator carried out her research while the jury was meeting and reported back as soon as she had gathered together a response.**

On the last day, all of the key recommendations were brought together. Pairs of jurors were assigned a theme by the group and asked to produce a simple visual representation of this. These presentations were rehearsed before a more formal presentation was made to the jury sponsors and the local MP who spent part of the afternoon talking with jurors about their ideas and recommendations. We felt this exchange was significant because consultation exercises have in the past been perceived as a threat by democratically elected representatives.

Jury findings

The final report was written by the researchers in consultation with jury members. It painstakingly catalogued issues raised by jurors and witnesses about the lived experience of SWB and came to be a kind of testament of it. It would no longer be possible for any local health or social care service provider to claim lack of evidence or knowledge about particular local problems. The enormity of the task was at times overwhelming:

There's that many things that are needed round here there was no way we could've come to a proper decision about exactly what we wanted. (Juror, follow‐up interview)

Despite this, jurors addressed the central question of ‘What would improve the health and well‐being of residents of SWB?’ by articulating community needs and strengths, and by making over 80 specific recommendations. Many of these recommendations referred to the health needs of children, young people, older people, carers, men, women, and people with mental illness. Lack of access to health and social care services, to healthy food, to education and training, to habitable housing, and to exercise opportunities were all emphasized with specific recommendations relevant to each. The jury also addressed the problem of dangerous traffic (using evidence from local children of near‐death experiences on their way to and from school) and lack of transport options for many residents. Most importantly, jurors made a strong case for agencies to find funds to support emerging community initiatives (such as the Community Care co‐operative, the community transport scheme, and a food co‐operative) as well as devising a local market garden and social spaces run by young people, for young people.

Very specific proposals were made about health‐care provision, which were used by the Health and Social Care Group in an application for a Healthy Living Centre. After much research and deliberation about primary care, the jury called for a service situated within SWB comprising a nurse practitioner, a health visitor with particular skills and interest in sex education and mental health, a community health development worker, and others to work through the health centre (i.e. family therapist, drugs workers, sexual health workers, chiropodists, occupational therapists, social workers and mental health workers).

Dissemination of findings

The task of following up the recommendations was given to the SWB Health and Social Care Group and all jury members were encouraged to attend. 18 However the integration of jurors into an already established group of professionals proved challenging as an exclusive ‘meeting culture’ eventually emerged. After the highly inclusive (and intense) nature of the jury sittings, some jurors came to feel sidelined and ignored amid professionals’ talk and behaviour and lost the motivation to remain involved. Our facilitation had been guided towards enabling jurors to view themselves as the experts of their communities with a legitimate part to play in bringing about change in their area. This belief was challenged once they interacted with lengthy bureaucratic processes and professionals who had their own knowledge and asserted their own expertise.

However, the steering group remained committed to following through the jury's recommendations with their participation and retained the active participation of two jurors. In an effort to ground the jury's recommendations in the concerns of the wider community, a number of other stakeholders were invited to discuss the recommendations with the jurors and the steering group. At this meeting the concerns expressed by the jury were compared with those in the three previous consultations on health‐care provision; there was remarkable consistency between them although some had been carried out many years before the jury.

Additionally, the steering group was interested in disseminating the jury's recommendations and gaining feedback from the wider community. Local community workers, volunteers and jurors spent many days standing outside local post offices, schools and shops with display boards talking with and listening to people on the streets. The majority of responses were very positive. People were also asked to fill in a collaboratively designed questionnaire about what they saw as important issues for the area. Almost 400 questionnaires were filled in (representing 2% of households in the area) giving support to the issues raised by the jury. Fruit and vegetables were offered to participants as payment in kind.

Feedback

Three months after publication, all health and social care agencies mentioned in the report attended a public meeting to respond formally to the recommendations. Hopes were high for this event, that concrete action would be reported and plans outlined to work on the wider concerns raised by the jury. However, one senior official later made a poignant observation:

When I attended the meeting to discuss action I found the same frustration in local residents as ever at the apparent inability of the professionals from agencies and institutions to respond creatively or swiftly to the residents concerns. Instead they were on the defensive, and indeed seemed to be speaking a different language, although they were, for the most part, sincere and well meaning. It was ever thus. (Local Councillor, personal communication)

Despite this, every agency sent a formal, written response to the Health and Social Care Group outlining their proposed course of action on the recommendations.

Action

For the jury commissioners, the primary purpose of the jury had been to better understand the needs of all sections of the community so that appropriate primary care services could be provided. Using the jury's deliberations as evidence, the community‐led Health and Social Care Group developed several funding bids and were eventually successful in establishing a health centre with a community health development worker, locally based health visitors, first contact nurse, anti‐bullying workers, and counsellors. This centre officially opened last year and has been hailed as a flagship both for the active participation of community members on its management board (jury members who have remained active for the past 4 years), and also for tackling inequities in access to health‐care. As well as working in the centre, all health workers provide outreach in local venues (in the local school for both children and parents, in the local factory, in pubs, in sheltered housing, and in the local family centre). The centre is promoted as a community venue. For instance, it is regularly used by local residents meeting to challenge a buildings demolition programme drawn up by the local council; it runs an open access baby clothes swopshop; it holds baby clinic sessions in the same spirit as mother and toddler groups; in collaboration with other local groups, it provides play facilities for children during school holidays. The effect of all this has been that working within an informal network of key activists, this health centre has become an integral part of the social infrastructure in terms of its work and its function.

It is now widely accepted that the generation of both health and ill‐health lies in people's social and physical environments and requires non‐health‐care policies and interventions to bring improvement. 19 , 20 , 21 This was recognized by a local GP in her evidence to the jury:

We see a lot of depression, a lot of unhappiness. That's a large part of our work really…in this area there's quite a lot of people with heart disease, chest problems, and of course back pain. I see a lot of back pain…Really we need to say we are medicalizing what is often a sociological phenomenon and we've got to think very carefully about how we tackle the problem. (Jury witness)

Jurors themselves were very clear about the effects of poverty and low paid work on their health. For example in conversation about men's health, jurors said:

Traditionally they bring home the bread don't they the men…If you've got a bloke that's got to go to work he's under pressure…If he don't go to work he don't get paid so there's no bills being paid and there's no money on table, there's no food for children or anything…So a man's got to go to work…I mean I've had it so I know and I mean you've got to go even if you're ill. (Juror)

He (juror's father) worked down the pit and it all collapsed on him see so it all started from there…all the roof caved in and you know he'd been underneath it and it's damaged him from that…he always keeps saying to me I'm sick of this, I'm sick of this. He said…I just want to be in a coffin. I said you don't want to talk like that. He said well that's how I feel…he's always walking up and down with two sticks. I'm scared of him going outside…. (Juror)

Throughout the week, jurors expressed a desire for a society based on social justice and democracy. Jurors recognized and wanted to challenge gender inequality:

I can't understand that you know, why the women should be the victims and yet they have to go for help and the man gets away with it and does it again. (Female Juror)

…what we're going to do is, we're going to take the macho men image away from us, away from younger kids…to actually being just a, just a person…. (Male juror)

They wanted to break down age barriers, they wanted to rebuild their community through play and creativity, they wanted control over their own lives, and most of all they wanted to be part of the solution, not the problem. Local people, they felt, should have more opportunities for participation in decision‐making, in particular with setting priorities.

We want to make sure what can happen will happen but we don't want to be pushed to one side as though it doesn't mater any more. ‘You got your ideas. Now we'll sit back in us offices and we'll work it out’. (Juror speaking at a follow‐up meeting with service providers)

The success of this jury process will rest on the extent to which its findings can be translated into wider change in social policy and practice and to which gains in health and well‐being can be observed in the long term.

Development of a grounded citizens’ jury model

Four principles underpin our grounded model of citizens’ juries: deliberation, integration, sustainability and accountability.

Deliberation

This is embedded within judicial and parliamentary practices, and we argue that a custom and practice of deliberation needs to be established within citizen decision‐making initiatives as a matter of course. Using opinion polls, surveys and other quantitative tools constructs the public and the public view as a fixed entity, as an already existing truth simply waiting to be extracted. Consultation without deliberation is we argue, not legitimate. 22

Over the last decade many writers have been at pains to problematize the concept and practice of deliberation itself. 23 , 24 , 25 Nevertheless, deliberative democracy has rightly been described as a ‘politics of transformation’ because the process of being engaged in deliberation can and does lead to the transformation of values and preferences for those involved 26 . We argue that using a grounded methodology would provide legitimate deliberative opportunities, 11 and would in this way explicitly enable hitherto silenced, alienated and marginalized voices to be heard.

Integration

Here we mean that the jury process must be embedded within the community where it happens. The subject under discussion must be of relevance to community groups and organizations, as well as individuals, and these should participate from inception to realization; knowledge from previous consultations must be integrated using local expertise, e.g. as witnesses and advisors; recommendations must be implemented using links with existing local networks in order for these to be credible and workable. Without integration, juries and other consultative activities will remain isolated and irrelevant.

Sustainability

It is now widely accepted that local consultation strategies need to be underpinned by sustained development work within communities to build general capacity to participate. We argue that this development work is also needed to generate capacity to listen and act with relevant policy makers, locally elected representatives, and agencies. 27 , 28 Professionals need to learn how to ‘listen strategically’ (that is, to effectively translate the outcomes of the process into practical action). Without this dual approach to capacity building, health improvement cannot be sustained.

Accountability

Although public consultation is now a key word for all agencies, there is no way in which citizens can hold policy makers to account as a result of consultations. The public view can still be ignored. In places like SWB, people already feel disassociated from the democratic process and are deeply mistrustful of outsiders, professionals and politicians. Continuing with one‐off, ‘snapshot’ consultations with no visible change, feedback or accountability simply reinforces alienation and apathy. While there is no legal requirement for public agencies to be held to account locally, the grounded citizens’ jury model requires a high level of commitment to the process, and its outcomes, from the commissioners and other key agencies. Local commitments to act on the results of jury deliberations need top be established before consultations begin.

Concluding remarks

Citizens’ juries have been used sporadically over the last few years as part of a growing movement for democratic renewal. While there has been some evaluation of the processes and outcomes in the immediate or short term, 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 it is unclear how effective such juries have been in making an impact on policy and practice in the longer term. Yet more and more consultations are carried out without much consideration (or resources) for what is to be done after the initial process is over. This is partly due to the heavy reliance by health and social care agencies on the extractive, incidental outputs of the consultation industry.

This network of academics, market researchers, consultants, trainers, advisors, and public relations workers has an ever‐increasing supply of new conferences, training workshops, toolkits, Do‐It‐Yourself Guides and How‐To Manuals to promote and sell; it has a plethora of fixed models of consultation that are formulaic and can be learned, packaged and replicated without being contextualized or situated. The guaranteed output of this process is ‘the public view’ in an unproblematic format, easily digestible by the policy process.

Peoples’ real experiences, their pain, fears, hopes, aspirations, dreams and desires get reduced to a report with bullet point executive summaries. The public view has been commodified – turned into a negotiated product that can be bought and sold on the market and like any other product, it can even be customized to suit. The citizens’ jury process is being used to produce more of these standardized ‘outputs’. Our aim is to begin to reclaim juries from the marketplace and locate it within the ambit of community development and community activism. 33

We take issue with the stereotyping of jurors as token passive people who are activated or empowered by a process that is done to them in four days by exotic strangers with no commitment or relationship to them or their communities. Far from enhancing democratic decision‐making, such ‘incidental’ consultations are deeply mistrusted. They can be seen as ‘social control disguised as democratic emancipation’, 34 as ‘technologies of legitimation’, 8 or they can simply become ways of deflecting criticisms of mainstream (un)democratic practice. 35

While we do not claim the events in SWB were grounded in every way, we believe they went some way towards providing a different context for citizens’ juries. Fundamentally, health can only be improved through the organized activities of communities and societies 36 and we feel a grounded citizens’ jury provides a useful tool for such badly needed activism in some of the UK's most marginalized communities.

Footnotes

A sense of community is being further eroded by a highly contested demolition/regeneration programme.

Evidence for this is contained in a Research Note on the Going for Green Pilot Sustainable Communities project located in South West Burnley, which reported on four focus groups conducted in the area in 1996 (CSEC, Lancaster University). Further evidence was gathered through testimonies by residents and expert witnesses through both citizens’ juries held in 1998 and 2000.

Two reports demonstrating need were published in 1995 (commissioned by the Locality Planning Team and Lancashire Family Health Services Authority). In 1997 the Locality Planning Team commissioned a further report to be produced from a residents’ perspective. This report highlighted the residents’ frustrations with continual consultation with no ensuing action.

Although this project was called a Citizens’ Panel it was in actual fact run as a community‐based citizens’ jury. However, community members of the oversight panel decided early on in the process that use of the word ‘jury’ was not appropriate in the community and they requested the use of the term Citizens’ Panel instead.

Three weeks were devoted to developing the confidence of these four members of the earlier jury to help design and deliver the training session. This work was primarily organized by a well‐known local community activist who chaired the first jury in an effort to kick‐start a community consultancy project. Funding was obtained from a community organization to pay jurors at an appropriate consultancy rate for their time and experience.

For example, on Day 2, jurors asked the investigator to find out how effective speed bumps were. The investigator contacted the Engineering Unit at Lancashire County Council who faxed their reply within the same day.

References

- 1. Department of Health . Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation. London: HMSO, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health . The NHS Plan: a Plan for Investment, a Plan for Reform. London: HMSO, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Department of Health. s.11 of Health and Social Care Act, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Local Authority (Overview and Scrutiny Committees Health Scrutiny Functions) Regulations, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5. For an account of the many reports and discussions being held by the Department of Health visit http://www.doh.gov.uk/involvingpatients/index.htm .

- 6. For an account of how various national strategies have impacted on health agencies see the Our Healthier Nation website http://www.ohn.gov.uk/ohn/ohn.htm (follow link for Healthy Communities).

- 7. Department of Health . Shifting the Balance of Power: the Next Steps. London: HMSO, 2002. See http://www.doh.gov.uk/shiftingthebalance/index.htm for current update. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harrison S, Mort M. Which champions, which people? Public and user involvement in health care as a technology of legitimation. Social Policy and Administration, 1998; 32: 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kashefi E, Weldon S. Community Responses to Drug‐Related Crime: South West Burnley Citizens’ Panel Report. Centre for Study of Environmental Change, Lancaster University, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coote A, Lenaghan J. Citizens’ Juries: Theory into Practice. London: Institute for Public Policy Research, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith G, Wales C. Citizens’ juries and deliberative democracy Political Studies, 2000; 48: 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stewart J, Kendall E, Coote A. Citizens’ Juries. London: Institute for Public Policy Research, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Department for International Development . Realising Human Rights for Poor People. London: DFID, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burnley Action Partnership. A Neighbourhood Renewal Strategy for Burnley, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hartley J. Health and Social Care in South West Burnley. Burnley: SWBCDT, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cornwall A, Gaventa J. Bridging the gap: citizenship, participation and accountability. PLA Notes, 2001; 40: 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thompson S, Hoggett P. The emotional dynamics of deliberative democracy. Policy and Politics, 2001; 29: 351–364. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kashefi E, Mort M. I'll Tell You What I Want, What I Really Really Want!. Institute for Health Research, Lancaster University, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Acheson D. Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health. London: HMSO, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whitehead M, Diderichsen F, Burstrom B. Researching the impact of public policy on inequalities in health In: Graham H. (ed.) Understanding Health Inequalities Buckingham: Open University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Whitehead M. The Health Divide In: Townsend P, Davidson N. (ed.) Inequalities in Health: the Black Report and the Health Divide. London: Penguin, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fearon J. Deliberation as discussion In: Elster J. (ed.) Deliberative Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998:. 44–69. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dryzek J. Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberals, Critics and Contestations. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sanders L. Against deliberation Political Theory, 1997; 25: 347–376. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Young I. Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Woodward V. Community engagement with the state: a case study of the Plymouth Hoe citizen's jury. Community Development Journal, 2000; 35: 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- 27. King's Fund . What's to Stop Us? Overcoming Barriers to Public Sector Engagement with Local Communities. London: Kings Fund, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pickin C, Popay J, Staley K, Bruce N, Jones C, Gowman N. Developing a model to enhance the capacity of statutory organisations to engage with lay communities Journal of Health Service Research and Policy, 2002; 7: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Armour A. The citizens’ jury model of public participation: a critical evaluation In: Renn O, Webler T, Wiedemann P. (eds) Fairness and Competence in Citizen Participation. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995: 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 30. McIver S. Healthy Debate: an Independent Evaluation of Citizens’ Juries in Health Settings. London: King's Fund, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barnes M. Building a Deliberative Democracy: an Evaluation of two Citizens’ Juries. London: Institute for Public Policy Research, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 32. White C, Lewis J, Elam G. Citizens’ Juries: an Appraisal of their Role Based on the Conduct of Two Women Only Juries. London: Social and Community Planning Research, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wakeford T. Citizens’ juries: a radical alternative for social research. Social Research Update 37, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Glasner P. Rights or rituals? Why juries can do more harm than good. PLA Notes, 2001; 40: 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harrison S, Barnes M, Mort M. High praise and damnation: mental health user groups and the construction of organisational legitimacy. Public Policy and Administration, 1997; 12: 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bambra C, Fox D, Scott‐Samuel A. Towards a New Politics of Health. Politics of Health Group Discussion Paper no. 1, 2003. [Google Scholar]