Abstract

Objective The aim of this study was to identify key domains of cultural competence from the perspective of ethnically and linguistically diverse patients.

Design The study involved one‐time focus groups in community settings with 61 African–Americans, 45 Latinos and 55 non‐Latino Whites. Participants’ mean age was 48 years, 45% were women, and 47% had less than a high school education. Participants in 19 groups were asked the meaning of ‘culture’ and what cultural factors influenced the quality of their medical encounters. Each text unit (TU or identifiable continuous verbal utterance) of focus group transcripts was content analysed to identify key dimensions using inductive and deductive methods. The proportion of TUs was calculated for each dimension by ethnic group.

Results Definitions of culture common to all three ethnic groups included value systems (25% of TUs), customs (17%), self‐identified ethnicity (15%), nationality (11%) and stereotypes (4%). Factors influencing the quality of medical encounters common to all ethnic groups included sensitivity to complementary/alternative medicine (17%), health insurance‐based discrimination (12%), social class‐based discrimination (9%), ethnic concordance of physician and patient (8%), and age‐based discrimination (4%). Physicians’ acceptance of the role of spirtuality (2%) and of family (2%), and ethnicity‐based discrimination (11%) were cultural factors specific to non‐Whites. Language issues (21%) and immigration status (5%) were Latino‐specific factors.

Conclusions Providing quality health care to ethnically diverse patients requires cultural flexibility to elicit and respond to cultural factors in medical encounters. Interventions to reduce disparities in health and health care in the USA need to address cultural factors that affect the quality of medical encounters.

Keywords: culture, cultural competence, cultural sensitivity, health disparities, physician–patient communication, physician–patient interaction

Introduction

The US health care system faces tremendous challenges in providing high‐quality health care to its increasingly diverse population. Although many minority patients prefer ethnic and language‐concordant physicians, 1 such physicians are seldom available because of their under‐representation in the health care work force. 2 Given shortages of ethnically and linguistically diverse physicians, concerted efforts are required to develop medical education programmes to train health care professionals to provide high‐quality care to multi‐ethnic populations. Such training would also serve to ameliorate ethnic disparities in health and health care. 3

Recognition of the US population's growing diversity and persistent ethnic disparities in health care has resulted in increased efforts to address cultural competence in health services. 4 For example, the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health developed national standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS standards) to address health care inequalities and make services more responsive to consumers’ needs. 5 Although these initiatives are facilitating improvements in health care for diverse patients, they focus primarily on recommendations at the health care organization level to promote cultural competence. In addition to these efforts, several valuable multi‐level conceptual frameworks of cultural competence have been developed. 3 , 6 , 7 These frameworks have advanced conceptual models of cultural competence, but similarly emphasize system‐level factors, and rely primarily on literature reviews and technical experts to define culturally competent care.

Efforts to identify the components of culturally competent health care from the perspective of ethnically and linguistically diverse consumers, in detail 8 and to define cultural competence at the level of medical encounters are lacking. Many physicians lack the necessary skills and knowledge to identify, understand and bridge differences in cultural values and practices that influence the medical encounter. 9 Thus, identifying the critical domains of cultural competence from the perspective of patients can guide the development of interventions at the clinical level. A patient‐oriented framework of dimensions of cultural competence would also facilitate the development of patient‐reported measures of the cultural competence of health care providers. Such measures could then be used to assess how cultural competence of providers is associated with patient outcomes, as outcomes of provider cultural competence training, and eventually as measures of the quality of health care (to the extent that the measures are found to be associated with patient outcomes).

The purpose of this paper is to understand from the perspective of patients of three ethnic groups as to how culture influences the quality of medical visits.

Methods

Focus‐group interviews were used to elicit information on how respondents think about the influence of cultural factors on their medical encounters. Using an open‐ended script, participants were asked: (i) What does the word ‘culture’ mean to you? and (ii) What do or don't your doctors understand about your culture or health beliefs that might affect your visits? These questions were part of a more comprehensive discussion about the quality of health care.

A purposive sample was recruited in the San Francisco Bay Area from senior centres, unemployment agencies, community health clinics, and a university. Inclusion criteria were: self‐reported ethnicity of African–Americans, Latinos or non‐Latino Whites; English‐ or Spanish‐speaking; 18 years of age or older; and at least one physician visit within the past 12 months. Emphasis was placed on recruiting vulnerable at‐risk patients (non‐English‐speaking, of low socioeconomic status, or ethnic minorities) as they were more likely to have experienced cultural issues during their medical encounters.

Groups were stratified so as to be homogenous on the basis of ethnicity, language (English or Spanish), gender, and age (18–49 or ≥50 years). Experienced moderators were linguistically, ethnically and gender‐matched to participants in most groups. Two moderators conducted each discussion of approximately 90 min. Focus groups were conducted at locations where participants were recruited; refreshments and a $20 compensation were provided. Discussions were audio‐taped, transcribed and translated if necessary. Translations were performed by professional bilingual–bicultural translators and verified against the audiotapes by bilingual–bicultural research staff. Participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire. Consent forms and the study protocol were approved by the university's institutional review board.

Analysis

Chi‐square analyses were used to examine ethnic differences in demographic characteristics of participants.

Two methods were used to code the qualitative data which consisted of the focus‐group transcripts: grounded theory (coding categories emerge from the data) 10 and a constant comparative approach (comparing as many similarities and differences as possible in the data to generate coding categories and their properties). 11 Two investigators coded transcripts using QSR's N5 Nud*IST qualitative data‐analysis software. 12 The unit of analysis was an identifiable segment of continuous speech or verbal utterance, referred to as the text unit (TU). Therefore, a new text unit occurred every time a speaker paused after completing a statement or a new speaker initiated a statement. Each TU, which ranged in length from a sentence to several paragraphs, was reviewed independently by coders who developed and assigned it a code (category label) that represented a meaning of the word ‘culture’ (first research question) or a cultural factor that influenced the quality of the medical encounter (second research question). Coders then discussed and reconciled differences in the codes and their definitions. Using the coding scheme agreed upon, coders then recoded all the TUs. The kappa statistic was used to assess inter‐coder reliability after application of the final coding scheme. Finally, all the TUs assigned to a specific code were evaluated to determine whether they accurately fit the definition of the code. Thus, verification of the accuracy of the coding scheme (conceptual categories, their definitions and the observations coded within each category) was carried out using both inductive and deductive methods. 10

The proportion of TUs was calculated by ethnic group for each code within each research question. Statements could not be attributed to specific individuals; therefore, counts (and percentages) represent the number of TUs categorized into each code. Data were stratified by ethnicity to ascertain ethnic‐specific patterns. After each ethnic group was analysed separately, cross‐group comparisons were made.

Results

Nineteen focus groups were conducted with a total of 163 participants (Table 1). In general, White participants were younger, better educated and more likely to be single than non‐White participants. African–Americans and Latinos were more likely to be unemployed and uninsured than White participants. The majority of Latinos were foreign‐born.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of African–American, Latino and non‐Latino White San Francisco Bay Area focus group participants

| Demographic characteristic | Ethnic group | χ 2 (P‐value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African–American (N = 61) [n (%)] | Latino (N = 45) [n (%)] | Non‐Latino White (N = 55) [n (%)] | ||

| Age [years; mean (SD)] | 50.6 (18.0) | 52.2 (20.1) | 41.5 (23.2) | 30.3 (0.0001) |

| 18–35 | 10 (17) | 12 (27) | 31 (56) | |

| 36–59 | 32 (54) | 13 (29) | 8 (15) | |

| 60–92 | 17 (29) | 20 (44) | 16 (29) | |

| Years of education [mean (SD)] | 12.2 (2.1) | 9.8 (5.7) | 15.2 (3.2) | 68.7 (<0.0001) |

| Less than high school | 18 (30) | 14 (61) | 6 (11) | |

| High school diploma | 28 (46) | 3 (13) | 8 (14) | |

| Some college or technical school | 8 (13) | 2 (9) | 13 (24) | |

| College graduate and higher | 7 (11) | 4 (17) | 28 (51) | |

| Sex | 1.2 (0.553) | |||

| Men | 33 (54) | 27 (60) | 27 (49) | |

| Women | 28 (46) | 18 (40) | 28 (51) | |

| Marital status | 7.5 (0.024) | |||

| Married or living with someone | 14 (23) | 14 (31) | 5 (9) | |

| Single, divorced or widowed | 47 (77) | 31 (69) | 49 (91) | |

| Employment status | 21.2 (<0.0001) | |||

| Employed | 28 (49) | 14 (35) | 44 (80) | |

| Unemployed | 29 (51) | 26 (65) | 11 (20) | |

| Insurance | 23.2 (0.0001) | |||

| Private | 10 (19) | 11 (27) | 21 (47) | |

| Public | 35 (67) | 14 (34) | 20 (44) | |

| Uninsured | 7 (14) | 16 (39) | 4 (9) | |

| Birthplace | 99.9 (0.0001) | |||

| US born | 57 (98) | 4 (9) | 45 (82) | |

| Foreign born | 1 (2) | 41 (91) | 10 (18) | |

The kappa statistic was 0.72 for definitions of culture and 0.87 for cultural factors that affected medical encounters indicating strong agreement among coders beyond that attributable to chance. 13

For the first research question on the meaning of culture, 199 TUs were coded with Whites contributing the majority of these statements (55%) and African–Americans and Latinos contributing almost equally (22 and 23%, respectively). For the second research question on cultural factors affecting the medical encounter, 1377 TUs were coded, with Latinos making the majority of these statements (46%) followed by African–Americans (29%) and Whites (25%).

Dimensions of culture

Eight dimensions or coding categories for defining culture emerged from the data; these are listed in Table 2 in the order of overall frequency (number of TUs assigned per code). The dominant interpretations of culture common to all three ethnic groups were: (i) a value system of shared norms, values and beliefs; (ii) manifest customs, such as food and music; (iii) self‐identification with broad, generally accepted racial/ethnic categories; and (iv) nationality or country of origin. A less salient view of culture that emerged in all three ethnic groups, was stereotypes about specific ethnic groups.

Table 2.

Dimensions of culture and number of text units coded per dimension by ethnic group

| Dimension and definition | Number of coded text units by ethnic group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African–American | Latino | Non‐Latino White | Total (%) | |

| Value system | ||||

| A system of shared norms, values and beliefs that define a group; includes morals and a general sense of what is right and wrong | 9 | 13 | 28 | 50 (25) |

| Manifest customs | ||||

| Observable aspects of culture that symbolize a group, such as food, music, movies, television shows, clothing | 3 | 7 | 24 | 34 (17) |

| Self‐identified ethnicity | ||||

| The extent to which a person self‐identifies with a specific racial or ethnic group | 15 | 7 | 8 | 30 (15) |

| Shared experiences | ||||

| A group's common experiences that create a sense of membership and bonding | 3 | 0 | 25 | 28 (14) |

| Nationality, country of origin | ||||

| The geographic area where one was born or lived during childhood | 4 | 9 | 9 | 22 (11) |

| Language | ||||

| The specific language that characterizes a group, such as those who are Spanish‐speaking | 0 | 0 | 14 | 14 (7) |

| Discrimination | ||||

| The sense that one is treated differently by others because of one's minority status, ethnicity or social standing | 4 | 9 | 0 | 13 (7) |

| Generalized stereotype | ||||

| A formulaic, simplified archetype of a particular ethnic group that ignores intra‐group heterogeneity e.g. ‘the Latino culture’ | 5 | 1 | 2 | 8 (4) |

| Total (%) | 43 (22) | 46 (23) | 110 (55) | 199 (100) |

The remaining themes were limited to one or two ethnic groups. One focus group composed of Whites described at length the view of culture as shared experiences that define a group, such as a drug or hip‐hop culture: ‘Our culture is staying clean …from an addiction that will eventually kill us, so in a way we're bonded together. We don't have a religion or ethnicity. What we have is we've been through the school of hard knocks and come out alive.’ Culture was described by non‐Whites only as experiencing differential treatment because of one's cultural background. Only Latinos viewed language as a way to distinguish among cultural groups.

Cultural factors affecting the medical encounter

Cultural factors that influenced the medical encounters of respondents are listed in Table 3 in the order of overall frequency. Cultural factors common to all three ethnic groups included: (i) complementary and alternative medicine, (ii) health insurance‐based discrimination, (iii) social class‐based discrimination, (iv) ethnic concordance of the physician and patient, and (v) age‐based discrimination. Issues related to modesty about one's body and submissiveness to physicians were mentioned by Latinos and Whites, but not African–Americans. Spirituality, involvement of the patient's family in health care decision making and ethnicity‐based discrimination were specific to the non‐White groups. The role of a ‘doctor culture’ was mentioned by African–Americans and Whites, but not Latinos. Finally, issues related to language, immigration status, and nutrition were specific to Latinos.

Table 3.

Cultural factors affecting the medical encounter and number of text units coded per factor by ethnic group

| Cultural factor and definition | Number of coded text units by ethnic group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African–American | Latino | Non‐Latino White | Total (%) | |

| Complementary and alternative medicine | ||||

| Physicians’ knowledge and acceptance of non‐Western, non‐biomedical or holistic approaches to healing or maintenance of health, such as massage therapy, acupuncture, meditation, herbal treatments | 60 | 26 | 151 | 237 (17) |

| Language and language‐based discrimination | ||||

| The effects of language on access to care and the quality of communication; the role of interpreters in visits with limited English‐proficient patients; physicians’ assumptions and/or differential treatment based on patients’ English language ability | 0 | 279 | 0 | 279 (21) |

| Health insurance‐based discrimination | ||||

| Physicians’ assumptions and/or differential treatment based on patients’ health insurance status | 83 | 37 | 40 | 160 (12) |

| Ethnicity‐based discrimination | ||||

| Physicians’ assumptions and/or differential treatment based on patients’ ethnicity | 103 | 49 | 0 | 152 (11) |

| Social class‐based discrimination | ||||

| Physicians’ assumptions and/or differential treatment based on patients’ economic or social standing | 53 | 31 | 45 | 129 (9) |

| Ethnic concordance of physician and patient | ||||

| The effects of ethnic concordance or lack thereof between patients and their physicians on quality of the communication, trust, and interpersonal relations | 66 | 17 | 23 | 106 (8) |

| Modesty | ||||

| Patients’ inhibitions associated with sharing information about or revealing sensitive body parts | 0 | 53 | 16 | 69 (5) |

| Immigration | ||||

| Physicians’ sensitivity to issues of recently immigrated patients, such as fears of deportation, acculturative stress, changes in dietary practices, and post‐traumatic stress | 0 | 61 | 0 | 61 (5) |

| Age‐based discrimination | ||||

| Physicians’ assumptions and/or differential treatment based on patients’ age | 4 | 7 | 41 | 52 (4) |

| Nutrition | ||||

| Physicians’ consideration of culturally relevant dietary factors without stereotyping | 0 | 33 | 0 | 33 (2) |

| Spirituality | ||||

| Physicians’ acceptance of the role of spirituality in patients’ adaptation and response to illness | 22 | 2 | 0 | 24 (2) |

| Family | ||||

| Physicians’ sensitivity to patients’ preferences for involving their families in health care decision making | 1 | 22 | 0 | 23 (2) |

| Patient submissiveness | ||||

| Patients’ views of physicians as authority figures and their deference to physicians | 0 | 8 | 13 | 21 (1) |

| Doctor culture | ||||

| Physicians’ emphasis on a biomedical model and lack of attention to patients’ subjective experiences of illness and attributions about the causes of illness | 3 | 0 | 8 | 11 (1) |

| Total (%) | 395 (29) | 625 (46) | 337 (25) | 1357 (100) |

Complementary and alternative medicine

Experiences about physicians’ acceptance of complementary and alternative medicines were mixed among African–Americans, with most indicating insensitivity to patients’ preferences. Some African–Americans felt that physicians were quick to dismiss their home remedies or were insensitive to cultural beliefs, such as those that forbid needle sticks. Others felt that physicians were more accepting of alternative treatments. As one woman stated, ‘I had a White physician and I hadn't discussed my cultural background growing up in the West Indies where all the treatment was herbal. So when I told her I was on estrogen, it was refreshing to hear…suggestions about alternative types of herbal treatments.’

A few younger Latina women wanted physicians to place more emphasis on prevention with attention to holistic mind–body connections. These women viewed yoga and meditation as practices to help address society's breakdowns in value, making statements, such as: ‘People are broken, and not just physically, you know?’

White respondents were knowledgeable about alternative medicines and reported trying holistic approaches on their own prior to seeking medical care. For example, one of the younger White women felt that biomedical approaches do not heal underlying causes and only mask problems. Although a few were skeptical of herbal treatments and holistic approaches, many preferred them to prescription medication and some indicated a willingness to pay out‐of‐pocket for physicians that would address mind–body connections and health.

Many White respondents reported that their physicians were not open to alternative treatments and overused prescription drugs. A few considered antibiotics as a last resort and felt that physicians pushed antibiotics, because of the influence of pharmaceutical companies. Some felt that physicians stopped listening when they brought up alternative medicine, which they felt was disrespectful to their beliefs. Several wished physicians were more knowledgeable about alternative treatments, such as chiropractic, massage, acupuncture and meditation, although they acknowledged a need for biomedical approaches for serious injuries. Many preferred integrated biomedical and complementary therapies.

Language and language‐based discrimination

The effect of language on the medical encounter was mentioned exclusively by Spanish‐speaking Latinos, focusing on the role of interpreters, satisfaction with the quality of care received, access to health care, and language‐based discrimination. Interpreters were thought to enhance communication and add cultural expertise. Even in the presence of interpreters, respondents felt that physicians needed to heed non‐verbal cues, stating: ‘If they have an interpreter, then the doctor should actually pay attention because you can get a lot from a person's facial expressions. I've seen doctors writing notes while the patient's talking in the different language.’ Spanish‐speaking respondents complained about longer wait times and the need to be assertive to obtain an interpreter. There were also complaints about interpreters’ and physicians’ impatience in language‐discordant situations.

Overall, Spanish‐speaking participants reported greater satisfaction with Spanish‐speaking physicians. They felt they received poorer quality health care than English‐speaking patients. Many Spanish‐speaking respondents stated they delayed seeking care because of fear of non‐Spanish‐speaking physicians, viewing this as the greatest obstacle to accessing care. A common perception was that medical office staff was usually much less willing to assist Spanish‐speaking patients than English‐speaking patients. However, a Spanish‐speaking Latina was pleased that her physician, who spoke limited Spanish, repeated questions until they understood each other.

Health insurance‐based discrimination

Experiences of discrimination because of having no insurance or Medicaid insurance were mentioned in all ethnic groups. Participants stated that even in cases of serious injuries, the first question medical staff asked was ‘Do you have insurance?’ and if they answered ‘no,’ the next question was ‘Do you have money to pay for the visit?’ Participants found this initial line of questioning insulting. Uninsured respondents described being made to feel grateful that any services were being rendered. A young White woman stated, ‘I just graduated recently and this is the first time I haven't had insurance. So, I almost felt like I deserved worse treatment, or I wasn't paying for it, so I shouldn't really complain.’ Many associated a lack of private insurance with inferior treatment, limited access to specialty care, limited access to quality health care and prescription medications, inadequate explanations, and longer wait times. Several found the public health system more intimidating and harder to navigate than a private physician's office.

Ethnicity‐based discrimination

For many African–Americans, the potential for racial discrimination and biased care existed in any first encounter with a racially discordant physician. Based on certain non‐verbal cues, such as maintaining physical distance from the patient or hesitancy to touch the patient or an object touched by the patient, respondents appraised physicians as acting on prejudice: ‘You get some type of bad vibe…the way a doctor treats you or picks up something that you've touched…standing a certain distance from you…jumpy. Then I try and determine if it's a doctor that's prejudiced, then it's somebody I really don't want to deal with.’ Some African–American participants felt that physicians sometimes made assumptions that they were intellectually inferior or drug users based on their race. African–Americans perceived that physicians treated them as equals when they were included in decision making.

Latino participants felt that prejudice manifested itself as assumptions. For example, a younger, English‐speaking Latina woman felt she was stereotyped by physicians as eating greasy food; another felt that a physician assumed she was a factory worker. Some Latinos felt they received less aggressive treatments due to their ethnicity because, as one person stated, ‘Doctors are racists, too.’

Social class‐based discrimination

Respondents of all ethnic groups spoke of class differences between physicians and patients that impeded good relations. Some comments about physicians included: ‘They discriminate against you because according to them, they are higher class than you,’ and ‘A lot of them think they're better than everyone. One particular doctor's attitude is that he's a superior being on the planet.’

African–American participants felt that physicians unconsciously stereotyped them based on their appearance: ‘And if I'm sick, I might come looking however I got up because I feel that bad. That doesn't mean I'm a particular type of person. They stereotype, and a lot of times doctors don't even know they're doing it because they've done it so much.’ Another African–American responded, ‘They make these judgments about you…It's an economic issue.’

Latinos and Whites reported receiving inadequate explanations because their physicians assumed that they would not understand: ‘I think there's a little assumption that if you seek public health care, you're in a lower class, therefore, your education might not be up to standards, like the way things are explained to you.’ Some stated that power differences between patients and physicians were accentuated when patients wear a paper gown. Younger White men and women described instances in which their use of medical terminology enhanced their role in the encounter: ‘I found when I used my vocabulary, it really changed the way people interacted with me. Because I said something like ‘‘Oh, it's kind of localized here,’’ all of a sudden the nurse said, ‘‘Oh you're so smart,’’ and like really let me into a lot more of the decision making.’

Ethnic concordance of physician and patient

Several African–American women stated they intentionally sought African–American women physicians because they could identify better with them, resulting in better communication. They experienced better comprehension of explanations and more positive relations when their physicians were ethnic concordant, although they found it difficult to articulate specific physician behaviours that generated these experiences. Respondents were clear that it was not the technical quality of the visit that suffered with an ethnic‐discordant physician, but the quality of communication. In general, Latinos and Whites did not feel that the physician's ethnicity affected the medical encounter, either positively or negatively as long as the physician was technically competent and versatile.

Modesty

Modesty was mentioned by older Latinas and older White men. Older Latinos stated that they often did not volunteer information out of embarrassment unless the physician asked. They commented they might forego medical visits for symptoms such as vaginal itching because of taboos about discussing reproductive organs. They knew of Latinas who were diagnosed with late‐stage cervical cancer because of fear of discussing symptoms, such as vaginal bleeding. An older Spanish‐speaking Latina stated: ‘Our culture is that a male doctor can't see us; it has to be a female doctor because you have your modesty, and you trust a female doctor more than a man.’ Older Latinas reported extreme embarrassment with gynecological examinations even with women physicians, although some physicians were sensitive to this. This embarrassment was compounded with non‐Spanish speaking physicians. Parallel concerns were raised by older White men who tended to prefer male physicians for urological examinations.

Immigration

Latinos’ immigration experiences affected their care in several ways. Some experienced post‐traumatic stress associated with civil war atrocities in their home countries. Another issue was provider insensitivity to the cultural shock of relocating to a foreign environment. Others feared that computerized medical records would be used to deport them. Some felt they received inhumane treatment by physicians because of their immigration status: ‘They assume because you are undocumented, you are not a human being. We are considered third class citizens because we don't have rights here. This is why we are afraid to file a complaint against the hospital if a doctor refuses to offer services. What if he calls immigration?’

Age‐based discrimination

Age‐based discrimination surfaced in all ethnic groups. Older respondents felt ignored, that their medical concerns were not taken seriously, and that more aggressive or newer treatments were withheld because of their age. In one case, a woman felt that her husband's leukemia had been diagnosed at an advanced stage because physicians ignored his complaints, attributing them to ageing. Participants stated that physicians could be more respectful to older patients by really listening, taking their concerns seriously, and presenting them with new treatments that might be beneficial.

Nutrition

Younger Latina women stated that physician's references to diets were appropriate, but could be viewed favourably or negatively depending on whether the comments were delivered in a condescending manner. A Latina felt that her physician's knowledge of the typical Latino diet enhanced his ability to provide nutritional counselling. Others mentioned that the nutritional recommendations of US physicians were contradictory to those of physicians in their home countries.

Spirituality

African–Americans talked about the pivotal role of their faith in managing medical concerns. They discussed entrusting medical decisions and their health to God and felt that physicians were generally sensitive to spiritual concerns. One older African–American woman commented, ‘I tell them, I'll trust you doctor, but also we have trust in the man above. That's my culture.’ Younger Spanish‐speaking Latinos commented that they were raised to solicit help from God for minor health problems and seek care from physicians only for serious illnesses.

Family

Among Latinos, and to a lesser degree African–Americans, inclusion of family members in medical decision making was viewed as necessary but often overlooked by physicians. Latinos especially felt that it was important for physicians to seek family input prior to making decisions about surgery or treatment of serious illnesses. For some Latinas, the family also influenced their likelihood of obtaining health care services because the husband's and family's health came first.

Patient submissiveness

Culture influenced the physician–patient interaction through role expectations. Latinos tended to view themselves as too submissive, feeling helpless and vulnerable, with the physician in complete control of the medical encounter. A young White woman stated that her culture as a White woman working in the health care field empowered her to ask questions and challenge information provided by physicians. A young White man described socially prescribed role expectations of physicians as authority figures, making patients reluctant to challenge physicians’ judgments.

Doctor culture

African–Americans and Whites perceived that because of time constraints, physicians’ systematic protocols for diagnosing and prescribing limited their flexibility and adaptability to patients’ individual needs. One African–American stated, ‘They pretty much have you on a monthly plan, where this is what you get every month. They just take blood samples and see where you're at depending on your ailment rather than sit down and take quality time.’

Younger white respondents identified the strongest culture in the examination room as the ‘doctor culture,’ a product of their medical training. This doctor culture was described by some as the greatest impediment to effective physician–patient communication. As one participant described it: ‘A doctor has gone to med school for many years. They are taught to look at a problem and solve it as quickly as possible and approach it in a very scientific way, whereas for us, it's ‘‘My throat hurts’’. ’ They elaborated that physicians are trained to approach illness in a deductive and objective manner, in contrast to patients’ subjective, personal experiences of illness, and that this difference is a primary threat to the patient–physician relationship.

Discussion

Culture played a significant role in the medical encounters of participants of all three ethnic groups. Based on the themes that emerged, physicians need to be cognizant of their patients’ use of complementary and alternative medicine; ways to bridge gaps introduced by language and ethnic discordance of patients and physicians; the potential for discrimination based on insurance status, ethnicity, social class, age, and immigration status; and interpersonal styles that are sensitive to modesty and submissiveness. Physicians also need to be aware of the potential roles of the family and spirituality in the medical decision‐making and healing processes. Finally, physicians need to be aware of the deductive and objective culture of medicine, which may be viewed by some patients as insensitive to their individual needs.

Based on our findings, specific recommendations for physicians to enhance the quality of medical encounters can be grouped into two general areas: interpersonal style and communication. Specific interpersonal characteristics of physicians viewed favourably included: (i) sensitivity to patients’ privacy; (ii) a humanistic approach; and (iii) treating patients as equals. Participants felt that to minimize embarrassment, it was important for physicians to place patients at ease prior to a physical examination or a discussion of sensitive topics. They suggested physicians adopt a humanistic approach even within time‐constrained visits and demonstrate interest in patients by sitting down and maintaining eye contact. Finally, patients suggested that physicians regard all patients with respect and as equals regardless of their linguistic, ethnic, birthplace, age or socioeconomic (including health insurance status) characteristics. Minority patients especially felt it was important for physicians to empower patients by encouraging them to ask questions and voice concerns as partners in their care.

The second major area for improving the quality of care pertains to effective communication strategies. Two general strategies emerged from patients’ comments: eliciting and responding to patients’ concerns, questions and preferences and providing thorough non‐technical explanations. The discussions reflected the importance of eliciting information from the patient rather than making assumptions about patients’ health beliefs, social or educational background. Physicians need to ascertain patients’ preferences for treatments including complementary and alternative approaches, non‐biomedical health beliefs, dietary practices, the family's role in decision making, and the role of spirituality. A provider's willingness to explore these attitudes and preferences was often interpreted by patients as a sign of respect and a basis for trust. Finally, physicians should not forego providing comprehensive explanations based on the assumption that patients will not understand them.

Much attention has been devoted to the development of cultural competence indicators as measures of quality of care due to the growing diversity of the US population and the need to eliminate health disparities. Cultural competence measures have been developed at the health plan or system level, but less work has been done to develop valid consumer‐reported measures that reflect cultural competence based on the perspectives of ethnically diverse groups. 14 Quality‐of‐care indicators commonly used in the US developed by the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA), the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), and the Foundation for Accountability (FACCT), generally do not address cultural factors.

Results from this and similar studies can be used to develop structured measures of quality of care that are relevant for minority patients and persons with limited English proficiency. Cultural competence is multidimensional and includes components that need to be assessed at multiple levels (e.g. medical encounter, group, health plan and administrative service delivery system). 15 Five of nine domains identified in a comprehensive literature review of conceptual frameworks of cultural competence reflected topics that need to be operationalized and validated as consumer‐reported indicators: values and attitudes; cultural sensitivity, communication; intervention and treatment models; and family and community participation. 7 Current measures of these domains consist of self‐assessments of cultural competence by health care professionals and staff regarding their own cultural competence; patient‐reported measures are limited to those that address language access.

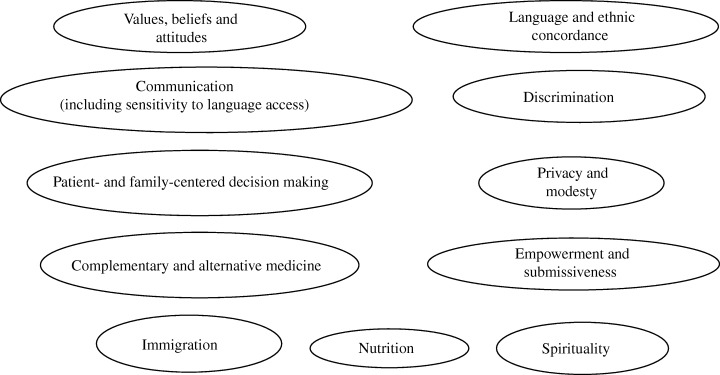

Our study corroborated the importance of values, beliefs, attitudes, and communication and decision‐making processes as key components of cultural competence from the perspectives of ethnically diverse patients; it also identified several domains of quality of care related to culture not represented in current quality measures (Fig. 1). For example, our results suggest that quality indicators might be expanded to include measures of language‐based discrimination and sensitivity of providers to language issues for patients with limited English proficiency. Our findings related to modesty suggest that the ability to elicit sensitive health information and respect for privacy might be important quality‐of‐care issues for particular ethnic groups. 16 The issues raised regarding complementary and alternative medicine suggest that quality‐of‐care measures should incorporate items pertaining to how sensitive providers are to patients’ use of these treatment modalities. Quality‐of‐care measures that incorporate culturally meaningful domains can then be used to evaluate the outcomes of physician training programmes and explore whether more culturally competent care reduces health disparities by improving patient outcomes.

Figure 1.

Consumer‐reported cultural competence domains.

Ethnic disparities in health status are associated with variation in the quality of health care. 17 A body of literature supports that minority patients, especially patients with limited English proficiency, are less likely than their White counterparts to receive empathy, information, and encouragement to participate in decision making. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 Consideration of cultural factors in the medical encounter may have a positive impact on these and other aspects of care such as communication and shared decision making. Improved interpersonal process of care may, in turn, positively affect perceived quality of care, adherence, and other outcomes, 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 and thus may help reduce health disparities. 8 , 14 , 24 , 31 , 32 For example, studies have linked language concordance of patients and physicians, and the provision of an interpreter to better glycaemic control among patients with diabetes 33 , 34 Race‐concordant visits have been associated with higher patient ratings of care among African–Americans. 20 Race and language concordance can be viewed as markers of unmeasured culturally influenced processes of care. Thus, current quality indicators that measure the interpersonal processes of care may need to be expanded, especially for more vulnerable patients.

This study identified components of cultural competence at the medical encounter level as perceived by ethnically diverse patients. These findings provide empirical support for conceptual frameworks of cultural competency that have focused on the domains of values, attitudes, cultural sensitivity and communication (including language needs). 9 , 35 , 36 , 37 Our findings also lend support to approaches that seek to train physicians on culture‐specific content (language access and modesty), and more generally, on interpersonal communication skills. 38 Additionally, our study points to the importance of training physicians in self‐awareness as a key component of cultural competence curricula and the need to examine experiences of biased care in assessing health care quality.

Overall, participants reported feeling more satisfied when they thought physicians demonstrated versatility in dealing with patients of diverse ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, and treatment preferences. This ‘cultural flexibility’ may be a useful concept to gauge the impact of a physician's ability to elicit, adapt and respond to patients’ cultural characteristics. If cultural flexibility can be operationalized in terms of specific interpersonal and communication strategies, future studies can employ such measures to assess its impact on outcomes of care.

As the US population becomes more ethnically and linguistically diverse, researchers, physicians and policy makers will need to incorporate cultural factors in assessing the quality of health care. Results from studies such as this one that seek to understand the cultural health beliefs, practices and preferences of patients can help to make health care services more responsive to all patients.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant no. RO1 HS10599 of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and grant no. P30‐AG15272 under the Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Nursing Research, and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1. Saha S, Taggart SH, Komaromy M, Bindman AB. Do patients choose physicians of their own race? Health Affairs, 2000; 19: 76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Affairs, 2002; 21: 90–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh‐Firempong O, II. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Reports, 2003; 118: 293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chin JL. Culturally competent health care. Public Health Reports, 2000; 115: 25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: The Office of Minority Health . National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health Care. Federal Register, 2000; 65: 80865–80879. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Medical Care Research and Review, 2000; 57 (Suppl 1): 181–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. The Lewin Group Inc . Health Resources and Services Administration Study on Measuring Cultural Competence in Health Care Delivery Settings: A Review of the Literature. U.S.: Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, USA, 2001. http://www.hrsa.gov/OMH/cultural/sectionii.htm, accessed October 14, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tucker CM, Herman KC, Pedersen TR, Higley B, Montrichard M, Ivery P. Cultural sensitivity in physician‐patient relationships: perspectives of an ethnically diverse sample of low‐income primary care patients. Medical Care, 2003; 41: 859–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kagawa‐Singer M, Kassim‐Lakha S. A strategy to reduce cross‐cultural miscommunication and increase the likelihood of improving health outcomes. Academic Medicine, 2003; 78: 577–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, Inc., 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Hawthorne: Aldine Publishing Company, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 12. QSR International . QSR N5 NUD*IST. Bundoora, Victoria: QSR International Pty Ltd, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bethell C, Carter K, D L, Latzke B, Gowen K. Measuring and Interpreting Health Care Quality Across Culturally‐diverse Populations: A Focus on Consumer‐reported Indicators of Health Care Quality. Portland, OR: Foundation for Accountability, 2003: 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Siegel C, Haugland G, Chambers ED. Performance measures and their benchmarks for assessing organizational cultural competency in behavioral health care service delivery. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 2003; 31: 141–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Warda MR. Mexican Americans’ perceptions of culturally competent care. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 2000; 22: 203–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Collins TC, Clark JA, Petersen LA, Kressin NR. Racial differences in how patients perceive physician communication regarding cardiac testing. Medical Care, 2002; 40: I‐27–I‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cooper‐Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient‐physician relationship. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1999; 282: 583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient‐centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2003; 139: 907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferguson WJ, Candib LM. Culture, language and the doctor‐patient relationship. Family Medicine, 2002; 34: 353–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hooper EM, Comstock LM, Goodwin JM, Goodwin JS. Patient characteristics that influence physician behavior. Medical Care, 1982; 20: 630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaplan SH, Gandek B, Greenfield S, Rogers W, Ware JE. Patient and visit characteristics related to physicians’ participatory decision‐making style. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Medical Care, 1995; 33: 1176–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA. Patient–physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. American Journal of Public Health, 2003; 93: 1713–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salganicoff A, Beckerman JZ, Wyn R, Ojeda V. Women's Health in the United States: Health Coverage and Access to Care. Menlo Park: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician–patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 2002; 15: 25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JEJ. Assessing the effects of physician–patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Medical Care, 1989; 27: S110‐S127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Like R, Zyzanski SJ. Patient satisfaction with the clinical encounter: social psychological determinants. Social Science & Medicine, 1987; 24: 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rose LE, Kim MT, Dennison CR, Hill MN. The contexts of adherence for African Americans with high blood pressure. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2000; 32: 587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Siminoff LA, Ravdin P, Colabianchi N, Sturm CMS. Doctor–patient communication patterns in breast cancer adjuvant therapy discussions. Health Expectations, 2000; 3: 26–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Ryn M. Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Medical Care, 2002; 40: I‐140–I‐151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio‐economic status on physician's perceptions of patients. Social Science & Medicine, 2000; 50: 813–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lasater LM, Davidson AJ, Steiner JF, Mehler PS. Glycemic control in English‐ vs Spanish‐speaking Hispanic patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2001; 161: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tocher T, Larson E. Quality of diabetes care for non‐English‐speaking patients: a comparative study. Western Journal of Medicine, 1998; 168: 504–511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Like RC, Steiner RP, Rubel AJ. STFM Core Curriculum Guidelines. Recommended core curriculum guidelines on culturally sensitive and competent health care. Family Medicine, 1996; 28: 291–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pena Dolhun E, Munoz C, Grumbach K. Cross‐cultural education in U.S. medical schools: development of an assessment tool. Academic Medicine, 2003; 78: 615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tervalon M. Components of culture in health for medical students’ education. Academic Medicine, 2003; 78: 570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carrillo JE, Green AR, Betancourt JR. Cross‐cultural primary care: a patient‐based approach. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1999; 130: 829–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]