Abstract

Objective To examine parents’ and health professionals’ views on informed choice in newborn blood spot screening, and assess information and communication needs.

Design and participants A qualitative study involving semi‐structured telephone interviews and focus groups with 47 parents of children who were either found to be affected or unaffected by the screened conditions, and 35 health professionals with differing roles in newborn blood spot screening programmes across the UK.

Results and conclusions Parents and health professionals recognize a tension between informed choice in newborn blood spot screening and public health screening for children. Some propose resolving this tension with more information and better communication, and some with rigorous dissent procedures. This paper argues that neither extensive parent information, nor a signed dissent model adequately address this tension. Instead, clear, brief and accurate parent information and effective communication between health professionals and parents, which take into account parents’ information needs, are required, if informed choice and public health screening for children are to coexist successfully.

Keywords: consent, dissent, health professionals, informed choice, newborn screening, parents

Introduction

Since the introduction of blood spot screening of all newborns for phenylketonuria (PKU) and congenital hypothyroidism (CHT) in the UK, in the 1960s and 1980s respectively, consent for screening has generally been assumed or implied. Usually, midwives looking after mothers and babies in their own homes during early postnatal visits, would gently forewarn mothers of the ‘heel‐prick’ to collect a little of their babies’ blood, portraying it as routine and no cause for concern. This was primarily because screening for PKU and CHT was known to be highly effective in preventing severe disability. More recently, however, this practice has been challenged by raised expectations for informed consent for treatment, screening, diagnosis and research. 1 , 2 Informed choice has been defined differently by a variety of stakeholders. Some refer to ‘choice’, others to ‘consent’ or ‘dissent’: our interpretation appears in Box 1. Promoting informed choice has increased awareness of the need to communicate clearly with parents about: their babies’ health; available tests and the potential consequences; and the choices they face. This is reflected in the growing research literature about communication for screening (see Special Issue, Health Expectations, 2001). 15 and in the reports of the UK National Screening Committee. The first report in 1998 addresses choices in light of screening results: treatment choices, lifestyle choices and choices about further tests. 3 In comparison, the second report in 2002 promotes informed choice for screening, and calls for (i) screening to be offered to individuals who are helped to make an informed choice about it and (ii) screening to be seen as a programme to assist in the early identification of diseases and not a guarantee of diagnosis or cure. 4 This has led to the proliferation of written information for parents, some of which addresses the benefits and possible harms of screening so that parents can make an informed choice about whether or not their baby should be screened. 5

Table Box 1 .

Elements of informed choice for newborn screening

| • Decisions are made voluntarily |

| • By parents who have considered and understood information about the screening, 12 including the benefits and risks 4 |

| • In line with their own values, 18 beliefs, wishes or priorities 21 |

| • To accept or decline screening for all or some of the conditions |

| • To accept or decline tests that identify carrier status |

| • To accept or decline follow‐up screening or diagnostic tests |

| • To accept or decline receiving invitations to participate in research related to the newborn blood spot screening programme |

| • The extent of parent choice to be offered with regard to the use of DNA analysis as part of screening, and the use of residual blood spots for wider public health purposes and research remain limited |

Demands for choice, however, are in tension with concerns about child health and current newborn screening practice. 6 Questions arise about whether choice will lead to reduced uptake in screening; 7 what information people need and its effects on their decision‐making; 8 and whether informed choice is appropriate for all screening programmes. 7 A parent refusing newborn screening for a very low prevalence condition with an unproven intervention would be more justified in making such a refusal than a parent refusing screening for a high prevalence, catastrophic condition which is easily preventable. 5 , 9 Newborn blood spot screening presents a range of scenarios between these two extremes (see Box 2), thereby raising tensions between parental autonomy and preventive public health strategies.

Table Box 2 .

Context of informed choice for newborn blood spot screening

| Approximately 600 000 babies each year, tested for serious but rare conditions: |

| • Eleven babies in every 100 000 births will have phenylketonuria (PKU), 22 a condition which affects the processing of a protein called phenylalanine that unless treated, can lead to serious developmental problems and mental disability by the time the child is 6 months old |

| • One in approximately every 4000 babies in the UK will have congenital hypothyroidism (CHT), 23 caused by a malfunctioning or missing thyroid gland. Babies with CHT lack the hormone thyroxine, needed for normal growth and development, and can become severely mentally impaired |

| • One in every 2500 babies has cystic fibrosis (CF), 24 a condition that affects the lungs and digestive systems, leading to chronic illness |

| • One in 2380 babies in the UK is born with a sickle cell disorder (SCD), 25 which causes the red blood cells to change to a crescent shape and become stuck in small blood vessels, causing pain, tissue damage and infection that can be fatal |

The UK Newborn Screening Programme Centre was commissioned in 2002 to set national standards for newborn blood spot screening; to develop policies and procedures for process standards, clinical consent, blood sampling, clinical referral, registration of affected cases, and storage and use of residual blood spots; and to develop parent information and communication guidelines and training for health professionals.

In order to develop these information and communication resources, we, the Parent Support Research Team of the Programme Centre, sought the views of parents and health professionals about their information and communication needs. Their views have informed the UK Newborn Screening Programme Centre's development of information resources for parents and health professionals; 10 and standardized referral pathways for babies thought to be affected by screened conditions. 11 This paper reports the findings that relate specifically to informed choice.

Methods

Sampling

Parents were purposively recruited for their diverse experiences of screening and the conditions, and socio‐demographic status. Parents of unaffected children were sought through statutory services [a suburban general practitioner (GP) surgery, an inner city statutory parent support group and a market town factory]. Parents of children found to be affected by the conditions were accessed through condition‐specific support organizations. Most parents had a child under 3 years old, and many of these had babies under 1 year old. Two parents attending one focus group had young adult children. Overall the ages of the children born to parents ranged from 6 weeks to 23 years. Health professionals were recruited through professional and service organizations, screening training events and a charity.

Interviews and focus groups

Telephone interviews and focus groups with 47 parents (42 mothers and five fathers) and 35 health professionals were carried out between July and October 2003 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Study participants

| Participants | Data collection methods |

|---|---|

| 19 parents of unaffected babies | 3 focus groups*; 1 telephone interview |

| 6 parents of babies with phenylketonuria | 1 focus group; 4 interviews |

| 10 parents of babies with congenital hypothyroidism | Interviews |

| 6 parents of babies with sickle cell disorders | 1 focus group |

| 6 parents of babies with CF | Interviews† |

| 6 midwives | Interviews |

| 4 health visitors | Interviews |

| 4 CF nurses | Interviews |

| 8 sickle cell counsellors/ specialist nurses | Interviews |

| 6 paediatricians | Interviews |

| 7 general practitioners (GP) | Interviews |

*One mother was also a midwife and participated in a focus group primarily as a parent, but commented briefly on her views as a health professional. Another mother was formerly a midwife and commented in a focus group on her previous experiences as a midwife.

†One parent was also a GP and was interviewed separately as a parent and as a health professional.

Recruitment

Participation in the research was voluntary, anonymous and confidential. Study information was distributed through contacts in health service and parent organizations, or sent directly to parents who responded to advertisements placed in condition‐specific support organization newsletters. Those who wished to participate were first asked to complete, sign and submit two consent forms, which were then signed by a researcher and one returned to the participant.

Data collection and analysis

Semi‐structured interview guides were developed for the different categories of parents. Topics included: experience of the heel‐prick test and the screening process overall including receiving results; the timing and format of information they received about the test; who provided the information; what, in retrospect, they would have liked to have known before the test; and issues related to informed choice and consent. In focus groups, parents were shown copies of leaflets about newborn screening, and asked for feedback on the information provided. Health professionals were asked about their role in the newborn blood spot programme, particularly in communicating with parents and delivering results, use of and access to useful information resources, views on informed choice and consent, issues and challenges in communicating with parents about newborn screening, and training needs.

The guides were piloted in initial focus groups and interviews and adapted to capture both the similar and divergent issues across the different categories of interviewee. All interviews and focus groups were tape‐recorded and transcribed. Two researchers analysed each transcript, identified themes, coded the transcripts and compared similarities and differences until data saturation was achieved.

Results

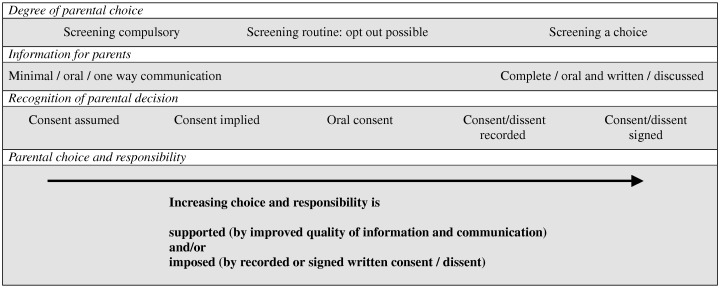

Analysis of the data revealed debates about a spectrum of circumstances relating to the degree of parental choice and methods for recording parents’ decisions (see Fig. 1). This spectrum ranges from no parental choice (mandatory screening) through routine screening, where opt out is possible although not encouraged, to full parental choice, where parents are given information about the benefits and limitations of screening and asked to choose whether or not to have their baby screened for any or all of the conditions. Different amounts of information, and different methods of communication, were described for supporting different positions along the spectrum. Minimal one‐way oral communication, with midwives advising parents of how their baby will be screened and for what, was associated with routine screening. A need for more complete information, and better communication supported by written materials, was anticipated as parental choice and parental responsibility are increased. The following sections summarize the findings that illustrate each of the continua described above and in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Elements of decisions for newborn blood spot screening.

Information for parents

Most parents recalled being minimally informed about newborn blood spot screening before the test, whether or not their babies were affected.

‘I can't remember anything being discussed with either of mine and told that it was actually done’ [Unaffected mother].

‘I don't recall being given very much information… I think [all] I knew about the heel prick test was that they check up for PKU. I had no idea that there was any genetic component to the testing’ [CF father].

Even with minimal information, most parents reported that they were happy to accept what they perceived as routine screening recommended by their midwife and the health service. Focusing on other priorities postnatally, parents paid little attention to the test and were unfamiliar with the conditions being screened. A mother said:

‘All I really remember about that was being told that if anything comes up positive, it can be treated easily. I can't remember [anything about the conditions]. …it's only 6 days after the birth, your head is all over the place, so I took very little notice of it. I hadn't had much sleep either. So I probably didn't listen to what she was saying if I'm truthful… and I remember actually thinking ‘‘oh that'll be fine, that'll be okay'’’ [CHT mother].

Other parents had received a leaflet as well as information orally from the midwife, and had discussed screening with the midwife.

‘I was given a leaflet on the day, [and] one earlier on and it was about the PKU and the congenital hypothyroidism… they also advised for [the baby] to wear some socks so that the feet were nice and warm. There's quite a good leaflet that they give, I've got it in front of me… there's a diagram… there's like half a page on PKU and congenital hypothyroidism’ [CHT mother].

Several parents, particularly those whose babies were later found to have one of the conditions, said they did not recall midwives drawing attention to the significance of the tests.

‘…even when we were in hospital they were saying ‘you know your midwife will be doing the heel prick test between 6 and 14 days’…. And then the midwife comes and says ‘‘right I'm going to do the test today and I'll prick the heel and bla, bla, bla’’ [but]… you've got no idea of the seriousness of it really. That's what it boils down to’ [PKU mother].

Most parents of unaffected children heard nothing more after the blood sample was taken having been told that ‘no news is good news’.

‘I knew something was going to happen because of the pre‐baby lessons you go to. That wasn't very informative. They just said they'd do this test. They never said why it was being taken… what information you'd get. And then when the baby was tested you just got absolutely nothing, nothing at all’ [Unaffected mother].

With hindsight, most parents see no need for detailed information about the screening tests or the conditions tested for before, or at the time of, the test.

‘You need to know basics really… I think it's good to know what the test is and that you're going to have it, remind us when you're going to do it, then… once the results are in, if it was positive then I would want to know more about it. I wouldn't want to know before because I'd be worried about the results’ [Unaffected mother].

‘I think you can be overloaded with information, and I think other than making the judgement that it's accepted practice to do it I think I'd be quite happy to go along with that… I don't really feel that I wanted detail of what exactly what tests were done or anything’ [CF father].

Prior, basic knowledge about the conditions and their implications was regarded as most significant when babies were found to have the conditions.

‘Having got the letter back saying it's fine, I'm not so bothered about the written information, but if there was a problem I'd be furious if I hadn't known earlier about the conditions’ [Unaffected mother].

‘You need to know from the beginning… what these initials stand for… I didn't know what PKU was… I didn't know what the consequences were. It would have been nice to know why the baby was having the heel prick and what these initials stood for’ [PKU mother].

Degree of parental choice

Most parents did not experience newborn screening as something they could choose or refuse on behalf of their baby; most perceived it as a routine test.

‘I'm very much in favour of [screening] being done… but on the other hand, parents do feel… around the postnatal period you do feel pretty pushed about and trampled over… er… anything that seems to give parents a wee bit more respect then… I don't think people are all that disrespectful, just that they've got other priorities’ [CF father].

If they had been offered a choice, many said they would have opted for their child to be screened.

‘I just assumed it must be important to do it. So, I just thought that's fine. If it'd been an injection I suppose you'd give it more thought. If it's a screening thing then that can only be good can't it’ [Unaffected parent]?

The strength of feeling favouring screening was strongest amongst parents of affected babies, most of whom considered that screening should be compulsory or at least routine.

‘I personally don't think [parents should be given a choice], because it's so important from the child's point of view, that if conditions are identified and managed for the benefit of the child er… I'm looking at it totally from the child's point of view’ [CF mother].

‘I don't see that you could have a choice really to be honest, because with something like the PKU, if they don't get it straight away… we were told by the time he was 6 months old, had he not had the test, that he would have been physically and mentally handicapped. So really I don't think that consent would be the right thing’ [PKU mother].

Some health professionals also thought that screening should not be a matter of ‘choice’ because of the importance of early detection of serious conditions (particularly PKU and CHT).

‘For the four things that are being tested, I would say definitely they need to have information. I'm not sure whether the element choice should be there… I think it should be something that is standard…particularly like for the PKU, because you know early treatment can mean lots of difference’ [Sickle Cell Nurse].

‘That's a very hard question because I think that you would actually be heading into Child Protection territory if they refused. Because the person who would suffer for the rest of their days would actually be the child’ [GP].

Whilst some health professionals indicated that parents should have a choice about screening, most expressed the view that there should be a strong expectation that babies should be screened:

‘It is such a tragedy if phenylketonuria is missed, and I think the same could apply to hypothyroidism. And I think that the parents should be told ‘‘Really this test needs to be done’’. …But obviously they do have a choice. They can refuse. Cystic fibrosis, well it's been the whole problem, hasn't it? Because cystic fibrosis is usually detected within the first year of life anyway, the evidence that treatment actually makes a difference is small. They do need choice obviously. I am quite happy with our arrangement in Wales, which is that it is an opt‐out choice rather than an opt‐in choice. Because it is a treatable condition and that seems reasonable to me’ [Paediatrician].

Some parents and health professionals who favoured informed choice, emphasized that if parents were well‐informed they would be less likely to decline screening, and that systems should be in place to minimize the possibility of refusals.

‘I do [support informed choice] in principle, but then I think if you end up missing a child that has a condition and the parents have refused… at the end of the day, I don't think you should take away parents’ choice… but I think like most things, if it's explained correctly then most parents will agree. I think it's when parents don't understand that they're more likely [to refuse]’ [Health visitor].

‘I think most people would accept it as a routine test as long as they've been given the information, and then if someone really refused then I think it's important that they sign something and that they're given all the [information] explained by a doctor, someone to explain all the implications of not having the test’ [PKU mother].

‘I'm a paediatrician and I think it comes down to… the child should have rights as well in this. So I do feel that yes, informed choice, but I think… informed decisions. I think you have to put the information that this is a test that should be done for the child and we're not saying ‘‘Do you want it or not''? to the mum. I mean I think that if a parent didn't want it I would want to remonstrate with them’ [Paediatrician].

Some parents, particularly those whose babies were unaffected by the conditions, said that screening should be offered as a choice. Others supported parental choice but raised the issue of this challenging the interests of the child.

‘No I think it should be a choice. Yeah it's the same thing in immunization, you give your consent don't you…’ [Unaffected parent]?

‘I think it should be available as a choice really, with a lot of information available to back it up. If a parent really wants to make a reckless decision that's going to impact on their children's health then they've probably got the right to take it, but I'm really not sure… it's a very difficult one’ [CF father].

Some health professionals advocated informed parental choice for screening, but expected that most would opt for screening to ensure that their baby did not have one of the conditions.

‘I think they need to know exactly what's going to be tested for and whether there's bits of it they can opt in and opt out of… I'm sure most mothers will want things tested to make certain there's no problem. But I think if they do opt out, it must be very well documented that they have not been tested because medical staff will assume that they have been tested on the Guthrie for x, y, and z and will not necessarily then investigate for it’ [CF Nurse].

Whilst most parents said they were unlikely to opt out of screening or parts of screening, one parent of an unaffected child did indicate that she might choose to opt out of screening for some of the conditions, particularly if there was some controversy over the value of screening for that condition.

Recording parents’ decisions

Many parents said they did not recall giving consent for the heel‐prick test.

‘It wasn't anything I consented to. I don't remember signing or agreeing’ [Unaffected mother].

Others recalled being given information orally by the midwife and giving verbal consent. There was some support for implied or verbal consent from parents and some health professionals, mostly from those who believed that screening should be routine.

‘…if the mother can't stand it and has to go out while the grandmother [holds the baby], then… they ought to have written consent then, but obviously if it's you actually holding the baby then that's implied consent anyway, if you're holding the baby's heel up’ [CF mother/GP].

‘I think a verbal discussion really between midwife and mother or mother and father to say, ‘‘we do this test and it's for so and so, have you any objections to us doing it''? And I think that's enough really. I mean you don't have to give written consent to have your inoculations or anything like that, do you’ [PKU mother]?

Some health professionals preferred a verbal consent model, but believed that in the current increasingly litigious climate, written consent might offer them greater legal protection*.

‘Well, legally, verbal consent isn't really satisfactory. If anything happens, say if the baby got an infected foot or the test wasn't done correctly, you know, verbal consent means very little really. A midwife's… word against the parent. Maybe they could have just a space there, consent for the test. It might be easier, without creating any more paperwork’ [Health Visitor].

When asked for feedback on a proposed model of verbal consent and written dissent, many health professionals and parents of affected children were in favour because it would make it easier for parents to give rather than withhold their consent.

‘I rather like that idea of verbal consent and written dissent. I mean to some extent it's already happening in the NHS. Some procedures are requiring written consent where they're actually essential procedures which would be negligent if you didn't do them… I would be wary of being overly bureaucratic. Enormous amounts of things we do are sort of verbal consent or even implied consent. I think paediatrics work on that. We don't ask for a consent form at the time we take a blood sample’ [Paediatrician].

Some health professionals, however, argued that consent and dissent should be treated in the same way; otherwise it might appear coercive. They also thought a small minority of parents would refuse to sign for dissent.

‘So they have to write to opt out, but don't have to write to opt in? …either they're writing a consent or not, I don't think you should have one rule for in and one rule for out. Who are you benefiting by putting that consent down? Are you covering your back or are you throwing it back at them later to say well you said… it's your problem? I'm quite happy for someone to give their verbal consent but then I would write down that they have given their verbal consent… whether you actually need for them to put a signature to it I don't know’ [Sickle cell counsellor].

Other health professionals, particularly midwives, supported the status quo of consent/dissent being documented by midwives in the antenatal record as part of best professional practice.

‘It's giving information first and then asking if women would agree to have this done, and documenting it in the woman's baby's notes. For all of these things apart from general anaesthetic, we don't actually give out consent forms because there are so many things we're gaining consent for. So, midwives are giving verbal information and getting verbal consent and then documenting that… [and would document and report any refusals]’ [Consultant midwife].

A significant number of parents, of both unaffected and affected children, and health professionals supported written consent, although some of these were happy with verbal consent. These parents argued that signing would make screening seem more significant, ensure that adequate information had been given, and clarify parental intentions.

‘Maybe [written consent] would make people think more of what… what actually you were having the test done for. You'd have to look into what the test was actually about. But I was quite happy with the verbal consent’ [CF mother].

‘If you have to give written consent, the chances are that you're reading what you're signing for… and that maybe you're disseminating information, because you're asking people to sign for it. I'm sure 99% people will sign it but at least it's one way of getting the information to us. Because we weren't really given anything to write or sign…’ [Unaffected parent].

‘I would have thought it would probably best to sign for it. Things can become so tenuous, I find, nowadays… everybody needs to be clear about what's happening and make sure that they actually understand what's happening and a signature would probably be a good idea’ [CHT father].

Other parents raised the issue of the need for written consent if blood spots are to be stored.

‘…if they're keeping the blood I think we ought to sign’ [Unaffected parent].

‘I mean I don't think anybody would have been too bothered with the verbal consent until they found out it's going to be stored for however long, then they sort of think ‘‘hold on'’’ [Unaffected parent].

Some health professionals also preferred both written consent and dissent because they believed it would protect them better legally, and provide a better record for the future as to whether or not screening had taken place.

‘[Consent] should be in writing and I also think that if they opt out from anything it must be in writing that they have opted out, because we had a situation where a child hasn't been tested for cystic fibrosis, but the parents were under the impression that they had been tested… It was a boundary problem …so we had been told by the parents that she had been screened and it was negative, when in fact she hadn't been screened and when investigated it was positive’ [CF nurse].

In conclusion, parents’ and midwives’ experienced screening that was virtually compulsory with little information and assumed consent. They supported improved information and communication for parental choice, albeit tempered by concerns about children's health.

Discussion

This research has shown that parents and health professionals recognize a tension between informed choice and children's health in the context of newborn blood spot screening. Some participants propose resolving this tension with better information and communication, and some with rigorous dissent procedures to mitigate the possibility of refusals.

Although this study includes the views of a small number of parents and health professionals who have had experience of newborn blood spot screening, its strength lies in its purposive sampling, which enabled us to elicit the range of views of diverse groups of parents and health professionals from a variety of geographic areas in the UK, and with a wide range of experiences and roles in newborn screening.

While every effort was made to include a variety of parents with differing perspectives and experiences of screening, and from differing socio‐demographic backgrounds, the participants to some extent were self‐selected in that they responded to advertisements or invitations to participate in the study and therefore had some degree of interest in the topic. The context of one‐to‐one interviewing with parents of affected children and focus group discussions primarily with parents of unaffected children may cause some discrepancy in the type and depth of information received from these parents. Some parents in focus groups, whose children were unaffected by any of the conditions, expressed limited views on screening. This may be because it is difficult to elicit people's views on a topic that has little impact on their lives, or because their babies, who were with mothers in two focus groups, distracted them. Showing parents of unaffected babies copies of leaflets was an effective way of eliciting views from them about the type of information they would have liked to have seen in a leaflet on newborn screening, but we did not elicit this type of feedback from parents in the context of one‐to‐one telephone interviews.

The findings of this study have been presented to mixed working groups of health professionals and parents who have responded favourably to the content, and drawn on it in the formulation of policies to support informed choice for newborn screening. 10

Other research supports our finding that parents generally report receiving little information about screening, and are not aware that they have any choice. 13 This is despite research suggesting that increased knowledge of screening, its aims and limitations, can improve parents’ experience of an affected result, 13 as well as false‐negative results. 14 Little is currently known about parents’ views about choice and information. One American study, published in 1982, suggests that parents do not want to be offered a choice about whether or not to have their baby screened, 15 but it is not possible to relate this finding to the UK, or to the current day. A systematic review has found more recently that knowledge and understanding is often poor before and after screening. 16 More research is needed into the relationship between informed choice, uptake of screening, and quality of the experience: as they are perceived by parents and patients; in terms of information required to implement such a policy; and the impact on decisions and health. Another review is currently underway on interventions for improving understanding and minimizing the psychological impact of screening, 17 which may bear relevance to this paper, and we await their findings with interest.

The wider screening literature also raises a possible tension between informed choice for screening and the need for detailed high quality information to support such a policy. Whilst informed choice is acknowledged as important there is uncertainty over what this means, how it might be implemented, and whether it can be evaluated. 18 It is acknowledged that implementing an informed choice policy takes time and costs money. 6 Furthermore, the role of the health professional is recognized as pivotal, with informed choice policies relying on the health professional to provide information and offer the choice. Research shows some health professionals are reluctant to offer fully informed choice. 14 Studies of the uptake of antenatal HIV testing, reviewed by Zeuner et al., 19 suggest that a woman's decision is influenced strongly by her midwife. 20 Raffle suggests that a fear of reduced uptake, as well as pressures on time to explain the limitations of screening results, leads to one‐sided public screening information encouraging screening, rather than supporting informed choice. 6

In drawing on these findings to inform policy and resources supporting informed choice for newborn blood spot screening, we have interpreted ‘better information and communication’ as succinct, evidence‐based oral and written, well‐communicated parent information about the benefits and limitations of screening that takes into account the level of information parents want in order to make a decision about having their baby screened. Rigorous dissent procedures have been developed that require exploration of the reasons for dissent and recording that dissent, but without a parent's signature. In written information and discussion, screening is strongly recommended by the National Health Service (NHS), but it is clearly stipulates that parents have a choice and may opt out. The research evidence of the influence midwives have on parents’ decisions highlights the need for standardized, clear communication guidelines, also developed to assist midwives in addressing the tension between parental autonomy, children's rights and state policy. These tensions may become more complicated as more conditions are screened for in newborns.

The empirical research presented in this paper, and the policies and resources it has informed, reflect Newson's theoretical exploration of the ethical dilemmas and tensions emerging from the interplay between parental autonomy, children's welfare and state policy. 9 Newson argues that whilst refusals for newborn screening may be morally unjustified, ultimately parents have the right to make such decisions about their child's welfare without undue interference from the state. The state, however, she argues, may be justified in exercising some ‘influence’ over parental decision‐making through the practices of health professionals.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the participants in this research project, those who commented on drafts of the paper and the organizations that helped recruit participants: the National Society for PKU, Children Living with Inherited Metabolic Diseases (Climb), British Thyroid Foundation, the Cystic Fibrosis Trust, the Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Centres, New Life (BDF), the Royal College of Midwives, the UK Newborn Screening Programme Centre expert groups, and the Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Counsellors’ organisation (STAC).

This work was undertaken by the UK Newborn Screening Programme Centre, which received funding from the Department of Health. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health. A South East Multi‐Centre Research Ethics Committee granted ethical approval for this study.

Footnotes

This view is not supported, however, by Department of Health guidance on Consent, which explains that a signature alone does not prove that the person was sufficiently informed about the procedure to make an informed choice. 12

References

- 1. Human Genetics Commission . Inside Information. Balancing Interests in the Use of Personal Genetic Data. London, UK: Department of Health Human Genetics Commission, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Medical Research Council . Human Tissue and Biological Samples for Use in Research. Operational and Ethical Guidelines. MRC Ethics Series, London, 2001; 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Screening Committee . First Report of the National Screening Committee. UK: Health Departments of the United Kingdom, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Screening Committee . Second Report of the National Screening Committee. Department of Health, London, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hargreaves K, Stewart R, Oliver S. Newborn screening information supports public health more than informed choice. Health Education Journal (in press). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raffle AE. Information about screening – is it to achieve high uptake or to ensure informed choice? Health Expectations, 2001; 4: 92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jepson R, Forbes C, Sowden A, Lewis R. Increasing informed uptake and non‐uptake of screening: evidence from a systematic review. Health Expectations, 2001; 4: 116–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Broclain D, Jepson R, Moumjid Ferdjaoui N. Influence of comprehensive versus limited information on consumers’ screening choices (Protocol for a Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library, 2004; 2: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Newson A. Should parental refusals of newborn screening be respected? Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stewart R, Hargreaves K, Oliver S. Evidence informed policy making for health communication. Health Education Journal (in press). [Google Scholar]

- 11. UK Newborn Screening Programme Centre . Policies and Standards for Newborn Blood Spot Screening – Launch Papers. UK: UK Newborn Screening Programme Centre, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Department of Health . Reference Guide to Consent for Examination or Treatment. UK: Department of Health, 2001. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk. Accessed on 23 March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pollitt RJ, Green A, McCabe A et al. Neonatal screening for inborn errors of metabolism: cost, yield and outcome. Health Technology Assessment, 1997; 1: 1–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Petticrew MP, Sowden AJ, Lister‐Sharp D, Wright K. False negative results in screening programmes: systematic review of impact and implications. Health Technology Assessment, 2000; 4: 1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Faden RR, Chwalow AJ, Holtzman NA, Horn SD. A survey to evaluate parental consent as public policy for neonatal screening. American Journal of Public Health, 1982; 72: 1347–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Green J, Hewison J, Bekker H, Bryant LD, Cuckle H. Psychological aspects of genetic screening of pregnant women and newborns: a systematic review. Health Technology Assessment Programme, 2004; 8: 1–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doust J, Mannes P, Bastian H, Edwards A. Interventions for improving understanding and minimising psychological impact of screening. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD 001212. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD 001212.

- 18. Marteau T, Dormandy E, Michie S. A measure of informed choice. Health Expectations, 2001; 4: 99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zenner D, Ades AE, Karnon J, Brown J, Dezateux C, Anionwu EN. Antenatal and neonatal haemoglobinopathy screening in the UK: review and economic analysis. Health Technology Assessment, 1999; 3: 1–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jones S, Sadler T, Low N, Blott M, Welch J. Does uptake of antenatal HIV testing depend on the individual midwife? Cross‐sectional study. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316: 272–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oliver S. How can health service users contribute to the NHS research and development programme? British Medical Journal, 1995; 310: 1318–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith I, Cook B, Beasley M. Review of neonatal screening programme for phenylketonuria. British Medical Journal, 1991; 303: 333–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grant DB, Smith I. Survey of neonatal screening for primary hypothyroidism in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland 1982–84. British Medical Journal, 1988; 296: 1355–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dodge J, Morrison S, Lewis PA et al. Cystic fibrosis in the United Kingdom, 1968–1988: incidence, population and survival. Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 1993; 7: 166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. The NHS Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Screening Programme . Policy For Newborn Screening ( http://www‐phm.umds.ac.uk/haemscreening/Documents/NewbornScreeningPolicy.pdf). Accessed on: 23 March 2005. The NHS Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Screening Programme, 2004, 1–5. [Google Scholar]