Abstract

Objective To explore consultation between people with communication disability and General Practice (GP) staff from the perspectives of both patients and staff.

Background Communication disability causes a particular problem in primary care. This issue has not yet been investigated from the perspective of both patients and GP staff.

Design Eight focus groups were held – four with GP practices, two with people with intellectual disability and two with people who had had a stroke. Picture symbols and Talking Mats®, a visual communication framework, were used to assist the participants with communication disability. Discussions were audio recorded and analysed thematically.

Participants Twenty GP staff, 12 people with aphasia and six people with learning disability were interviewed.

Results GP staff expressed frustration with not being understood and not understanding but there was a lack of awareness of the reasons behind these difficulties. They all said they mainly relied on carers. They recognized the significance of poor communication in terms of access to health services and agreed that the extent of the problem was greater than they had previously believed. People with communication disability described significant problems before, during and after the consultation. Although some acknowledged that they needed help from their carer, most objected to staff speaking to the carer and not to them.

Conclusions The main priorities for GP staff were the need for relevant training and simple resources. The main priorities for people with communication difficulty were continuity of staff, trust, better GP staff communication skills, and less reliance on carers.

Keywords: aphasia, communication disability, general practice consultation, learning disability, primary care

Background

People with communication disability are more likely than the general population to have conditions requiring health intervention yet they are the group who have most difficulty accessing health services. 1 Communication disability causes a particular problem in primary care as inadequate communication can result in wrong diagnosis, inappropriate medication and can prevent the client's access to proper assessment necessary for receiving adequate healthcare service. 2 , 3 , 4 The way in which General Practice (GP) staff interact with patients who have a communication difficulty can be viewed as a ‘litmus test’ for how they treat all their patients. 5 However, it is important to recognize that communication requires the interplay of both practitioner and patient and also to acknowledge that there are constraints of time and resources for GP staff.

In Scotland there has been additional emphasis on GP communication since the implementation of The Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act which has been effective from July 2002. 6 Before examining or treating patients the healthcare professional must get consent from the patient. The Act stresses the importance of determining a person's capability to understand decisions, make decisions, communicate decisions, retain the memory of decisions and to act. It also states that, in the community, the GP is the professional who should determine whether or not a person is ‘incapable’ of the above in relation to health issues. The Act also emphasizes the statutory requirement to take account of wishes and feelings of those patients, that these can ‘be ascertained by means of communication appropriate to the adult’ and this may require the help of other specialists such as speech and language therapists. Application of the Act's principles and provisions should ensure equity of access to health care and enables health professionals to deliver health care lawfully.

It is particularly difficult to obtain the views of people with a communication disability because the GP has to both ensure that the patient understands what is said to them but also make their own opinions known.

Because of these problems, people with communication disability are almost always excluded from research projects. Previous studies by the author used an innovative low tech visual communication framework, Talking Mats® (AAC Research Unit, Stirling, UK), and found it to be a powerful tool to help people with a range of communication difficulties express their views. 7 , 8 , 9 This has been confirmed in a 3‐year project funded by the Scottish Executive to evaluate the effectiveness of Talking Mats® (J. Murphy, L. Cameron, I. Markova et al., Scottish Executive, Edinburgh, unpublished report).

Current study

This paper describes the findings from an original research project carried out in 2004 and funded by the Scottish Executive, which made further use of Talking Mats®. It explored consultation between people with communication disability and GP staff from the perspectives of both patients and staff. The research questions were:

-

1

How do GP staff consult with people with communication disability about their health concerns? What enhances understanding and what makes it more difficult?

-

2

Would specialist training in understanding communication disability be of value? If so, what should such training involve?

-

3

How do people with communication disability express their health concerns in consultation with general practitioners? What enhances understanding and what makes it more difficult?

Methodology

Focus group

Focus group is a research method based on open‐ended group discussions that explores a particular issue or a set of issues. Focus group discussions provide a forum for exploring the attitudes, perspectives and impressions of people who share common experiences. 10 A focus group is defined as ‘a group of individuals assembled by researchers to discuss and comment from personal experience the topic that is the subject of the research’. 11 As this project aimed to capture the views of homogeneous groups about the shared experience of GP consultation, focus group was considered the most appropriate method.

Participants

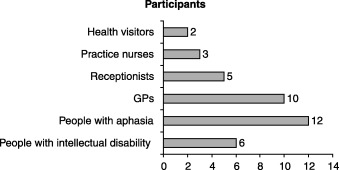

Eight focus groups were held with a total of 38 participants (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The role of the participants involved.

Ethical approval

The project received ethical approval from the relevant NHS Ethics of Research Committee and information sheets and consent forms were adapted to taken into account the receptive and expressive difficulties of participants.

Focus groups

Each focus group included participants who had common personal experiences of the research topic. Four focus groups were held in different GP practices to allow the staff working together in the same practice, with the same range of patients, to consider and develop their views relating to their specific GP practices. At the initial meeting to explain the project, GPs suggested including receptionists and nurses to provide a wider perspective.

Two focus groups were held with adults with intellectual disability who were members of a local action group. A further two focus groups were held with adults with aphasia from Speakability, a national charity that works with people with aphasia to overcome the barriers they face. In total 18 participants with communication disability, including aphasia, dysarthria, dyspraxia and delayed language took part in the study. All the participants had a comprehension level of three or more key words in one sentence and understood the nature and the purpose of the study.

The format of the focus groups was to ask the participants to consider and discuss communication at each stage of the visit – before, during and after the actual consultation – and the same topic prompts were given to all groups (Appendix 1, [Link]). All discussions were audio recorded. In order to assist the participants with communication disability, picture symbols and Talking Mats® were also used.

Analysis

The tape recordings were transcribed verbatim, then read and listened to several times for familiarization with the data. The data from each focus group were analysed using progressive thematic analysis to take into consideration not only what the participants said but also how they developed their arguments and negotiated issues in question. 12 Factors that related specifically to the issues covered were extrapolated and cognitive maps were drawn to represent each group's perceptions and the connections between them. Once each group's map had been drawn, individual maps were combined into more complex ones in order to compare patterns and to highlight reflections.

Findings

How do GP staff consult with people with communication disability and what enhances and what makes communication more difficult?

There was a lack of awareness among GP staff of the extent of the problem, both in terms of the range of communication disability that exists and the number of people with communication disability presenting at surgeries. GP staff did not appear to be aware of the subtle yet substantial difficulties experienced by people with mild aphasia or intellectual disability and simply assumed that they would rely on carers.

The following excerpt illustrates how the participants in one GP group viewed the extent and nature of the problem initially but gradually realized that their perception might be skewed by relying so much on carers:

Researcher: Can you think of patients in this area?

Doctor 26: No, there's nobody – I've had people coming in, more with learning disabilities, it's all the learning disability ones that spring to mind….

Doctor 27: There's a lot of autistic patients as well, that's because we tend to be associated with the Autism homes – and they're very difficult to communicate with.

Doctor 26: A lot of the time it's guesswork. Change of behaviour, and it's guesswork – everywhere.

Researcher: What about people, say who've had a stroke?

Doctor 27: They could write, you know write the answer, if they couldn't speak. Takes a wee bit longer.

Nurse 29: Strokes will usually come with their spouse because they're older, or a daughter, it's very much they come with them.

Doctor 27: I suppose, there is this whole thing of our perception of it and their perception of it, and that we don't think we have a lot of people that give us a lot of problems, because we seem to be quite happy with the carer speaking for them.

This excerpt illustrates the dependence on carers and reasons for it but also an awareness of the problems of relying on carers:

Doctor 26: Well they usually come with someone else, they usually come with a carer or spouse and it's usually the carer will speak.

Researcher: And how does that feel from your side?

Doctor 26: I probably in most instances probably presume because these – the carers, are usually very highly motivated to try and help the patient, so they've done – they've really tried to get to the route of the problem before they come.

Doctor 27: And then in some instances we can ask some more directive questions and they can indicate yes or no, but I would say in most instances the communication is done with the carer.

Nurse 28: The assumption is that the carer is representing them, but how can you know, because you don't actually know the patient? I mean you try and involve the person with the disability or speech problem as much as you can because you don't want them to feel that they're like an ornament sitting there while everyone else talks around them.

Before consultation

It was acknowledged that the waiting room itself created problems for people with communication disability such as lack of privacy and embarrassment at having to try to speak in front of other patients:

Doctor 32: They're exposed, they come out and they stand there totally exposed.

General Practice staff were initially unaware that finding the consulting room might be a problem for people with communication disability. This led to discussion of the pros and cons of having a buzzer system to alert people to their turn vs. the doctor coming out to meet them in the waiting room:

Researcher: What about the waiting room?

Receptionist 37: There's a tannoy system to tell them which room to go to….

Doctor 36: The girls are very aware by and large of the people that are likely to have a problem, and you can hear who's getting called as well and the girls tend to keep an eye out.

Doctor 36: And if we call them a couple of times, by and large the Doctors will phone through and say – especially if we know them and know that they have a communication problem y'know if we know that we have to shout our heads off because of their hearing aid and such like.

Researcher: Right, right, and what about the actual rooms?

Doctor 36: Yeah, they've got the name…and the number. We do, not infrequently, have people asking where rooms are, especially since we opened our seventh consulting room which is down a different corridor, so we have people wandering around…and it's either the first second or third on the left or the right, or the first one down the corridor here or round the back for M.

Receptionist 37: I think if people were finding it hard anyway…I've seen me in the corridor and they'll say where's room such and such, and I'll take them along.

Receptionist 38: But I've found it surprising recently that people come to the Doctors and they don't know the room numbers.

Doctor 36: They don't remember.

Receptionist 38: You never think though that there could be a problem with reading.

Doctor 36: Yeah….

A different GP group had this discussion:

Doctor 21: With us – the Doctor comes out him or herself. It's just always been a habit with us, I think it's a good habit for all kinds of reasons…I think it's polite for a kick off.

Receptionist 22: I think it makes it that wee bit personal as well.

Doctor 21: It's a bit more personal and I think you can tell a lot by somebody's first reaction to there name being called.

Doctor 20: Walking up the length of the corridor you can tell a whole lot.

Doctor 21: A huge amount just by the reaction to their name being called, y'know, how they put their magazine down, watch them get up, exchange of pleasantry, watch them walk up the corridor. You can assess how people are. And by the time you've sat down you've captured a good start on how things are going to go.

During consultation

The GP groups expressed the frustration they felt during the actual consultation and complained of patients forgetting appointment times, poor understanding on both sides and lack of time. However there was limited awareness of the reasons behind these difficulties:

Doctor 21: A lot of hassle and anxiety, a lot of frustration, because trying to get the message across if they can't get their formation right or they forget what they want to say when they come in.

One GP group came to the conclusion that continuity was a key factor with patients with communication difficulty:

Researcher: So what do you do if you're faced with someone who's trying to tell you what is wrong with them and they've a real problem communicating that?

Receptionist 22: You've got to try and guess in a way and hope that they can respond to you in some sort of yes or no form or whatever.

Doctor 20: Depends – if the communication problem is they don't know how to say what they're trying to say, then I think you have to just try and find out how they communicate and try and get into it.

Doctor 21: I'm probably incredibly patronizing but it would be rather like that two Ronnie's sketch where the guy's in the shop and he's kind of adding in or guessing all these words to kind of complete the sentences, and when you get a nod you‘ve got the right word.

Receptionist 22: But if you guess in the hope to get to the right suggestions, there's nothing worse and it gets worse and worse.

Receptionist 22: With Mr B it was easier once I got to know him. But at the beginning it was very difficult.

Doctor 21: I think that's a huge factor – it helps if you know the person‐continuity.

After consultation

General Practice staff made no comments about the problems patients might have in explaining the doctor's advice to family or carers once they had gone home. When pressed further, they thought it might help to give something in writing or to have the district nurse make a follow‐up visit.

When prompted to propose solutions to the problems, the main suggestion was ‘to rely on carers’, not only to make appointments, but also to speak for the patient and to carry out any instructions following the consultation. Other suggestions were made such as getting to know the patient better, making a double appointment to give them more time and watching the patient for non‐verbal clues.

In summary, GP staff often struggle to communicate with people with communication disabilities, particularly if they do not know them well, and tend to rely on carers. Previous knowledge of the person was considered the best way to enhance communication.

Would specialist training in understanding communication disability be of value? If so, what should such training involve?

None of the GP staff said they had received any training on communication disability and when the possibility of training was introduced, reactions were mixed. They all felt that time was the main obstacle to training and that because they might not use it regularly they would forget it. When specific training based on the findings from the study was suggested, there was clear interest and offers to pilot materials. Some suggested using visual material such as pictures, models and communication books but stressed that they did not have time to learn about communication aids.

General Practice staff were also asked about involving other professionals for help but they appeared to have limited understanding of the role of the speech and language therapist:

Researcher: Do you contact anybody else to get help? (silence)

Researcher: Like…I don't know…. Like a speech and language therapist?

Doctor 32: A social worker specializes in people….

Doctor 34: For the blind – yeah. We don't have one at the moment.

Doctor 30: I know there's interpreting services but that's moving to a different side of things really isn't it?

Doctor 32: Well there's a gentleman I've asked to come back with somebody who can speak. I'm trying to think there was somebody I referred on because we were having major problems. I can't remember what it was, but it was just one instance – a couple of years ago and we didn't know what was going on and so I referred to a speech therapist to try and get to the route of what the problem was and then come back. It's only once that I've ever, ever done that.

Another practice felt that speech and language therapists were difficult to get hold of:

Doctor 21: I don't know that there's enough of you, quite frankly. I think mostly when you phone the department you end up getting an answering machine because people are busy and understandably so. So if you're in a situation where you need somebody to help you – the way of it is that the person with the communication disorder presents at you with no warning, they want something done and you just have to get on with it the time. You've not, if you've got some kind of warning and these things can be organized, then great.

Doctor 20: Well yeah it's okay for routine things but, when it's acute things.

In summary, GP staff agreed that they would benefit from training in communication disability provided it was practical and simple to implement but they appeared unsure how to get specific help.

How do people with communication disability express their health concerns in consultation with GP staff? What enhances understanding and what makes it more difficult?

As the experiences and views of the participants with aphasia concurred and overlapped with those with intellectual disability, their comments have been combined. The specific speech diagnosis was irrelevant in relation to the type of functional difficulty people were reporting. There were considerably more comments from the people with communication disability than from the GP staff and the participants found it useful to hear other's views and to support each other.

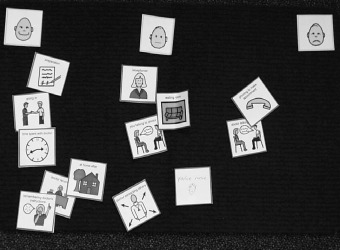

The following photograph is a completed Talking Mat constructed by one of the groups of people with aphasia. They each placed and moved the symbols on the mat to help them express their different views. They found Talking Mats® helped them observe and listen to each other's experiences, consider their own experiences, and agree or disagree as appropriate (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Photograph of group Talking Mat.

Before consultation

All four groups described problems when using the phone to make their appointment. Some had difficulty dialling the number; some could not cope with the speed of the receptionist's speech; some had difficulty understanding time; some were unable to write down the date and time of the appointment given and all said that auto‐attended calls with voice menus were particularly hard to use. For everyone, continuity was crucial and they all said it was important to get an appointment with a doctor who knew and understood them but that this was often difficult.

They all found the waiting room stressful for a variety of reasons. Some found it noisy:

Participant 10: Sometimes the phones start to get to you…ringing was something that gave me great problems…I call it the starling effect…it's just like starlings in your head.

Others were anxious about the lack of privacy in the waiting room and feeling that people were watching them as they struggled to speak to the receptionist. Some worried that they might not find the correct room because they could not read the number or name on the doctor's door. Several described feelings of panic before they even saw the doctor as this excerpt from a group with people with learning disability illustrates:

Researcher: How about when you're just sitting in the waiting room, how do you feel.

Participant 6: I feel nervous.

Participant 7: I fidget, well I get nervous because I'm in there and I dunno.

Participant 6: Just walk about the floor.

Participant 7: Well I'm not I'm calm when I go but, once I go in I start oh god (panicky).

Participant 5: Aye it's just the way we feel, aye.

Participant 6: Some people get constipation – I tend to go to the toilet more.

Participant 7: I have constipation as well and I get seriously sore stomach with it.

Participant 5: That must be nerves, that's nerves. I have sore stomachs too.

Participant 6: I go to the toilet a lot of times.

Participant 6: A lot of people don't explain things we don't know about. It depends on if a person like me can hear, like, sometimes I can pick things up wrong but the Doctor speaks in a simple language. Sometimes she say a Latin word and I say what does that mean – you're talking in Chinese (laughter).

During consultation

Participants were aware that difficulties with communication damaged their relationship with their GP:

Participant 12: I just don't understand him and he doesn't understand me and it gets you off to a bad start.

The groups talked about their concern that doctors do not always understand the nature of communication difficulties such as aphasia and the subtle problems faced by patients such as understanding complex language and reading difficulties.

When discussing the actual consultation with the doctor there was clear agitation amongst the participants. They described difficulty remembering what to say, not being understood, feeling the doctor did not believe them, being rushed and not following what the doctor said because he spoke too fast and used words they did not understand:

Participant 9: I'll always say something like ‘you won't remember but I've had a stroke, I'm aphasic and I'm garbling a bit this morning’.

Participant 10: We've muddled through it, we've got there. So I would say he's quite good as long as I remind him that eh, he cannae just speak too fast and then throw me out.

Participant 13: But I still sometimes I can't always get it in it. I've got to say ‘what was it?’ It's not really very good you know. Bcoz, you know they just go ‘hurry up hurry up hurry up’– there's no point – it gets, just be quiet just leave it where it is and just leave it, y'know.

Although some acknowledged that they needed help from their carer, most of them wanted independence and privacy and objected to the doctor speaking to the carer and not to them, particularly when they felt the carer had a different agenda from them. One man, who used a LightwriterTM communication aid competently, told the group:

Participant 16: The doctor never asks me a question because it takes too long and instead always speaks to my brother.

For those whose carer went with them they preferred the carer to be ‘a second pair of ears’ rather than take over the consultation:

Participant 11: I speak until I get tongue‐tied, and then the wife comes in (laughter).

Participant 9: Can I ask a question? If it was a male problem that you could get embarrassed about would your wife do that just the same?

Participant 11: Not so well probably (sigh).

Participant 8: Yeah I mean if I started gibbling a bit I'm not sure my husband sometimes answers my bits and they're not what I wanted to say – he does that all the time – he carries on conversations for me. It's not what I want to say sometimes – well he sometimes works it out.

Researcher: So what do you do?

Participant 8: I get angry. He does that, and my daughter does that very much as well, they think I'm not stupid, but they think I'm sometimes I panic and I answer in full which I'm not I just can't get the words out. Sometimes then when I go I've got mixed up what it was we actually agreed. I'll say that's just not what I want that's not what I'm asking. I want you to tell me this.

After consultation

The purpose of any visit to a doctor is that the patient's problem should be understood and that there should be a positive outcome. This did not always seem to be the case. Participants worried that they could not understand what advice they had been given and were unable to explain what the doctor had said once they went back home:

Participant 13: They tell you so much that by the time you get home, you really cannot remember it, as you should.

Positive experiences

Not all comments were negative and several participants described positive experiences, most noticeably when they saw a familiar receptionist or doctor who they felt understood their communication difficulty and gave them enough time.

A number of positive suggestions were made about how things could be better. They all preferred the doctor to come out of his/her room to ‘collect’ them and some suggested that pictures as well as written signs around the surgery would help those with reading problems. One woman took the responsibility to explain to her doctor what aphasia meant. Others prepared lists of problems both to aid their memory and to help explain their illness. Some booked a double appointment so that they would not feel rushed. They all felt it would help if the doctor spoke slowly and clearly and gave them something in pictorial and/or written form to explain and to take home to their carers.

In summary, the people with communication disability had strong views about the difficulties they experienced in consulting with their GPs and had a number of positive suggestions. They all thought there should be better training about communication disability for GP staff.

Discussion

It was extremely difficult to get GP practices to agree to be involved in the project initially and the lack of GP staff experience in how to deal with people with communication difficulty was obvious from the comments. Many did not understand the nature and implications of communication disability and appeared to use a reactive rather than a proactive approach with few strategies in place apart from relying on carers. During the interviews comments from GP staff were not always forthcoming but as the discussions progressed GP staff appeared to become more cognizant of the issues and became more responsive. Staff acknowledged the significance of poor communication in terms of access to health services and admitted that the extent of the problem was perhaps greater than they had previously believed.

They agreed that the experience of visiting a GP includes much more than just the actual time spent in the consulting room. The initial preparation made by the patient can have a significant impact on the consultation; the manner in which the patient is dealt with by the receptionist is crucial; the waiting room itself can affect the patient's experience and the implementation of advice once back home is jeopardized by poor communication. They also acknowledged that it was not enough to simply rely on carers and that patients’ health might suffer if their views were not taken into account. Some suggested that improving communication skills could benefit all patients, corroborating the proposition that ‘people with communication difficulties serve as a litmus test for whether practitioners are truly sensitized to the impact of their own communication skills’. 5

However the general attitude to communication and the importance of striving for a balance in the interaction appeared to be missing and there was still a clear message that the GP staff were in the position of communication control.

The participants with communication disability responded enthusiastically to the focus group discussions and found the group setting helped them compare and develop their views, especially as they felt strongly about the particular difficulties they had encountered. Talking Mats® helped explain the issues to be considered and allowed them to share their views more easily.

The findings from this study also raise issues relating to speech and language therapy as GP staff either were not aware of the role of the speech and language therapist or felt they were difficult to contact and get advice from.

Conclusions

People with communication disability are entitled to the same health services as others. Where patients find GP consultations stressful or unsatisfactory they lower their expectations, attend less and feel generally disaffected. This results in ineffective health care. This small study has compared the perspectives of GP staff and people with communication disability on the same issues relating to GP consultation and has identified a number of barriers to effective communication.

The main priorities for GP staff were the need for relevant and timely training and simple resources. For people with communication disability their main priorities for better communication were continuity of staff, trust, better GP staff communication skills and a reduction in reliance on carers.

Implications

Many people with communication disabilities may be unable to alter their ability to understand and/or express themselves. What can be altered are the communication environments in which they find themselves and the manner in which other people interact with them. Not only do GP staff require information about communication strategies and specific simple tools to help improve consultations with people with communication difficulties, but also require more knowledge about communication disabilities in order to change their attitude and reduce the barriers that exist in their workplaces. There is a clear role for speech and language therapy to liaise with GP practices to raise awareness, not only of communication difficulties, but also of the ways in which communication can be improved. Ultimately, better communication will have benefits for all patients, not just those with an obvious communication disability.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on a study funded by the Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Executive titled – Consultation between General Practitioners and people with a communication disability – CSO reference number: CZG/2/100. Support was also received from the Research and Development Office at Forth Valley Primary Care Operating Division. All symbols are courtesy of Mayer‐Johnson Inc. (http://www.mayer‐johnson.com). The Author would like to thank all the participants who gave their perceptions and time.

Appendix 1

What do you feel about…?

-

•

How patient prepares before coming to see you;

-

•

Phoning to make the appointment;

-

•

Talking to the receptionist when they arrive …;

-

•

The waiting room;

-

•

When patient comes into consulting room;

-

•

The patient talking to you and telling you what is wrong…;

-

•

How well you understand the patient;

-

•

Talking to the patient;

-

•

How well the patient understands you…;

-

•

The amount of time you spend with the patient…;

-

•

The patient bringing someone with them they come to see you;

-

•

Recording information about the patient;

-

•

Contacting other professionals for further help;

-

•

The patient remembering your instructions afterwards;

-

•

What happens when the patient gets back home….

References

- 1. Yeates S. The incidence and importance of hearing loss in people with severe learning disabilities: the evolution of a service. British Journal of Learning Disability, 1995; 23: 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Howells G. A general practice perspective In: O'Hara J, Sperlinger A. (eds) Adults with Learning Difficulties. New Jersey: Wiley and Sons Ltd, 1997. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beange H, Bauman A. Caring for the developmentally disabled in the community. Australian Family Physician, 1990; 19: 1555–1563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Department of Health . The Health of the Nation: a Strategy for People with Learning Disabilities. London: Department of Health, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Law J, Bunning K, Byng S, Farrelly S, Heyman B. Making sense in primary care: levelling the playing field for people with communication difficulties. Disability and Society, 2005; 20: 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scottish Executive . Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act. Edinburgh: The Stationary Office Ltd., 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hemsley B, Balandin S. Without AAC: the stories of unpaid carers of adults with cerebral palsy and complex communication needs in hospital. AAC Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 2004; 20: 243–258. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cameron L, Murphy J. Enabling young people with a learning disability to make choices at a time of transition. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 2002; 30: 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Murphy J. Enabling frail older people with a communication difficulty to express their views: the use of Talking MatsTM as an interview tool. Health and Social Care in the Community, 2004; 13: 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rice PL, Ezzy D. Qualitative Research Methods: a Health Focus. London: Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Powell RA, Single HM. Focus groups. International Journal of Quality in Health Care, 1996; 8: 499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Markova I. Focus Groups. Moscovici S. Methodes dans les Sciences Sociales. Paris: PUF, 2002. [Google Scholar]