Abstract

Introduction Examination of the existing literature in respect of health expectations revealed both ambiguity in relation to terminology, and relatively little work in respect of how abstract theories of expectancy in the psychological literature might be used in empirical research into the influence of expectations on attitudes and behaviours in the real world. This paper presents a conceptual model for the development of health expectations with specific reference to Alzheimer's disease.

Method Literature review, synthesis and conceptual model development, illustrated by the case of a person with newly diagnosed, early‐stage Alzheimer's disease, and her caregiver.

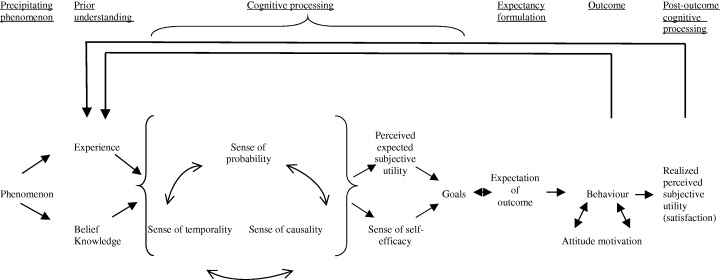

Outcome Our model envisages the development of a health expectation as incorporating several longitudinal phases (precipitating phenomenon, prior understanding, cognitive processing, expectation formulation, outcome, post‐outcome cognitive processing).

Conclusion Expectations are a highly important but still relatively poorly understood phenomenon in relation to the experience of health and health care. We suggest a pragmatic conceptual model designed to clarify the process of expectation development, in order to inform future research into the measurement of health expectations and to enhance our understanding of the influence of expectations on health behaviours and attitudes.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, health expectations, social psychology, theory development

Introduction

This paper derives from an examination of the theoretical literature in relation to expectation, in the context of a study into lay and professional expectations of Alzheimer's disease and the care provided for it. At the heart of this work lies an appreciation of the importance of expectations. Expectations contribute to an individual's psychological and physiological health (the placebo effect, for example, may account for up to 55% of any reported therapeutic benefit in relation to pain control 1 ), and to the work of health professionals providing care, where the management of patient and caregiver expectations of care, and of its outcome, are major, day‐to‐day requirements.

In reviewing the existing literature in relation to health (and health‐care) expectations, the most frequently cited conceptual framework we identified was that by Thomson and Sunol. 2 They identified four ‘types’ of expectation: ideal (desired or preferred outcomes); predicted (actually expected outcomes), normative (what should happen), and ‘unformed’. In considering this classification, we thought that in many ways it was problematic, mainly because it does not adequately address actuality. For example, so‐called ‘ideal expectations’, constitute hopes, desires, preferences, wants and needs, and may not have any bearing on actual (or ‘real’) expectations at all (as in ‘hoping for the best, but expecting the worst’). Normative expectations may also have no association with actual expectations. Unformed expectations, in being either nascent or unarticulated, cannot be considered as being actual expectations either, until their formation is complete. More importantly, the Thompson and Sunol model is explicitly designed to examine the role of expectations in the formation of satisfaction. While accepting that there is a relationship between expectation and satisfaction, our particular interest lay in understanding the process of expectation development, with specific reference to the influence of that process on health attitudes and behaviours, rather than on satisfaction specifically.

Olson et al. 3 proposed a simple model of expectancy processes which summarizes the major elements relating expectancies to subsequent behaviour. Their model identifies three antecedents to an expectancy: direct experience, other people and beliefs. However, their emphasis is on the cognitive, affective and behavioural outcomes of the process, rather than on the processes of expectancy interaction itself. In our view, understanding the process of expectation development is vital for guiding future research into practical aspects of the issue.

Returning to first principles, we have therefore tried to ‘anatomize’ the concept of a health expectation by reviewing the theoretical literature on expectancy, in order to develop a conceptual model which clarifies the components of an expectation and illuminates their interaction in the process of expectation development.

In asking ‘what is an expectation?’, two things rapidly became clear. The first was that in the psychological literature, the term ‘expectancy’ is used to identify the general concept, while ‘expectation’ is used to identify specific examples of expectancy in the real world. The second was that, with the exception of the Thompson and Sunol 2 and Olson et al. 3 frameworks, we could identify no literature that sought to translate the psychological concept of expectancy into a pragmatic and relevant conceptual model that might be used to underpin research into the attitudinal and behavioural sequelae of health expectations per se.

This paper focuses on the latter. In deference to psychological theory, we also use the terms ‘expectancy’ and ‘expectation’ to differentiate between general concepts and specific applications. We begin by describing some broad concepts and definitions of expectancies, and follow with our proposed conceptual model, which attempts to describe the process whereby an expectation is realized. This is illustrated by material drawn from a research interview, involving a person with early‐stage dementia and her caregiver. The interview derives from fieldwork undertaken in a study exploring the phenomenology of expectations relating to Alzheimer's disease and its care, from both lay and professional perspectives. Approval for this study was granted by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary.

Conceptual issues

The concept of expectancy has been discussed by a variety of authors and applied to many different subjects, ranging from work motivation to hypnosis. Broadly speaking, expectancies are stored associations between behaviours and resulting consequences, which then guide subsequent behaviours. 4 Because they are influential in guiding behaviour, aiding recognition and influencing understanding, 5 expectancies are an important aspect of human experience. However, they are not easily recognized, 6 being both conscious and unconscious 7 , and may vary in scope from the highly circumscribed to the very broad. 8

Expectancy development

We assume that expectations are socially and culturally contingent, since they are governed by one's understanding of the world, and form in relation to the social and cultural contexts within which one is located, including one's position with respect to larger political and historical factors. 9 , 10 , 11 Nevertheless, expectancies remain unique to the individual who holds them; as they develop over time, expectancies help to generate consistent behaviour, otherwise known as personality. 12

According to Stewart‐Williams 13 , there are three ways by which an expectancy may be acquired: by direct personal experience with a behaviour and its consequences; through the suggestion of others (this may be demonstrated by placebo effects 14 ); or by observing others. As expectancies develop, they acquire a particular strength, and when similar experiences in specific situations occur, expectancies become stronger and more resistant to change. 15 This ‘strength’ is regarded as being one of two ways in which expectancies differ, the other being the importance of the anticipated response to the individual. 16

Developing a conceptual model for health expectations

Following the work of Maddux, 17 we consider that many individual ‘taxonomies of expectancy’ (including, for example, those of Bandura 18 and Kirsch 19 ), may be considered as deriving from the same family of theories. Maddux calls these ‘social‐cognitive’ theories, which share common principles and processes.

The social‐cognitive approach appears to be useful for a pragmatic conceptual model of expectations which has relevance in the real world. This is important for our purpose, because in the context of health services research, what is important is not so much the detailed and highly abstract concepts of expectancy, but rather an understanding about the processes whereby an expectation is formed, and how it relates both to prior behaviours and attitudes, and to subsequent ones. In considering this, we identified several key elements a priori. The most obvious was that the process of expectation formulation is both cyclical and longitudinal in character: it is cyclical in that a trigger phenomenon causes an expectation about the future, which influences subsequent behaviour and attitudes, which, in turn, influence expectations in response to subsequent trigger phenomena; at the same time, within this process, expectations may be broken down into a series of individual, simple, longitudinal causal relationships (if this is the trigger, expect that as the outcome). We conceptualize this longitudinality as consisting of a number of phases or processes. Each phase itself contains one or more aspects.

In the light of this, we developed a preliminary conceptual model which describes the process (see Fig. 1). We have illustrated the model using data drawn from two research interviews, one with a woman with early‐stage Alzheimer's disease, ‘Mary’ (a pseudonym), and the other with her friend and caregiver, ‘Denise’. Mary's illness had been recently diagnosed. She and Denise consented to participate in separate, semi‐structured, home interviews, focusing upon their expectations regarding the newly identified disease and the medication prescribed for it. Both interviews were audio recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for the process of expectation development.

We suggest that the component phases within expectation development, which become active more or less in longitudinal sequence, include:

-

•

a precipitating phenomenon;

-

•

a prior understanding;

-

•

cognitive processing;

-

•

expectancy formulation;

-

•

outcome;

-

•

post‐outcome cognitive processing.

Precipitating phenomenon

We suggest that the process starts with the experience of a precipitating phenomenon, which functions as the trigger for a sequence of subsequent processes. For example, for Mary, the event that led to her referral to a geriatrician was getting lost while driving home from her nephew's house, a short distance away. As Denise explained:

She had gone over there one evening when I was away. She took the car and she came back and it's straight, you come down and it's first left, second left, and you're home. She ended up the other side of town. Completely lost with no idea where she was…

Prior understanding

Previous experience

When a precipitating phenomenon occurs, be it a physical event or a mental or imaginary experience, we suggest that it is compared with previous experiences of similar events and information. This comparison constitutes our ‘prior understanding’ of the precipitating phenomenon, and involves the activity of a set of social and cognitive imperatives which derive from our knowledge and beliefs in relation to the event:

When I think back, I kind of wonder if it wasn't slowly coming on, shortly a year or so after we moved here…because I can remember one night I went over to my nephew's who lives over there, on the next street…and I got in my car and I got lost and I thought well, you know I couldn't believe it! … You know, not to think well maybe I'm over one street, you know, [that is, one street further away from where she thought she was] it was kind of strange. That was the first time and then after that I'm not too – I remember maybe I didn't have too many more things like that happen. But my memory has gotten slowly worse. [Mary]

In this extract, Mary is comparing the precipitating event with her previous experiences of similar events, to put it into context. At the same time, she re‐interprets her previous experience in light of the precipitating event.

Knowledge and belief

It is not the intention of this paper to differentiate between the epistemological bases of knowledge and belief. Both may be conceptualized as stored information about different domains of previous experience of the world, including personal and collective understandings, spiritual or religious faith and teachings, dreams, direct encounters with other entities or situations, and contact with other people. Knowledge and belief may facilitate comprehension and direct behaviour. 18 They constitute a set of assumptions about the physical, social, cultural, psychological, and emotional ‘rules’, whose actions realize what we consider to be ‘normal’ in day‐to‐day living.

Our prior understandings of the world, including our personal experiences of it, are very influential in the formation of expectancies 3 , 9 , 13 about events. For Mary, prior understanding of her experience of a memory problem was summed up by her judgement that in her previous experiences, and in the development of her prior knowledge and beliefs, her cognitive functioning had been effective and reliable:

Well, you know, I guess because I've had such a good memory. (starts to cry) [Mary]

Cognitive processing

The core of our model describes what we term the ‘cognitive processing’ phase. The first aspect of this is represented by an individual's sense of subjective probability, causality and temporality, which are interrelated, possibly simultaneous, and mutually influential.

Sense of probability

Subjective probability is the likelihood a person attaches to something occurring. 20 Applied to expectations, subjective probability varies. For example, a factual expectancy is associated with the experience of complete certainty that a predicted outcome will occur. 3 On getting into her car, Mary had no doubt that she would successfully get to where she wanted to go, save for some external impediment (traffic, weather, etc.):

I got in my car and I got lost and I thought well, I couldn't believe it. [Mary]

Processing the sense of subjective probability is important in relation to the strength of any subsequent expectation: a sense of high probability will be associated with a strong expectation. 16

Sense of causality

Alongside a sense of probability, we suggest we cognitively process our experiences in the context of a sense of causality. This may be summarized as an understanding that one event or action is, recognizably, the result of a previous event or action. The relationship of causality to behaviour may take two forms. ‘Internal’ causality occurs when we see outcomes as a result of decisions we have made 21 or due to skills we possess. 22 ‘External’ causality occurs when the results are seen as a consequence of chance 23 or characteristics of an individual that are deemed beyond their control. For an expectancy to form, an individual must recognize this causal association between the stimulus or behaviour and its resulting outcome. 24 The emphasis is on the act of recognition as much as on the nature of the association. It represents the beginning of an attempt to provide an explanation for either the concordance or discordance between what did happen, and what we had expected to happen. Furthermore, it is an explanation which meets a subjective condition of being logical or reasonable. In Mary's case, attempting to find an explanation for a memory lapse led her to posit a systemic cause, even if the identity of the system was unknown:

And so it's (my memory) just recently gotten worse to the stage you wonder, I just feel that there's gotta be something causing it. [Mary]

Once an expectation is formed, it may be more readily preserved when it is seen as being externally caused, rather than internally. According to social learning theory, individuals who see outcomes as externally caused base their expectations on outside factors such as luck or chance; therefore, these expectations do not change as readily because the outcome can vary with factors beyond the individual's control. Persons who view outcomes as contingent upon their own behaviour modify the strength of their expectations according to the particular outcome that is achieved by the preceding behaviour. These expectations increase in strength when a particular outcome is achieved by a particular behaviour or set of behaviours, and these are therefore more dynamic than externally caused expectations. 22

Sense of temporality

All human behaviour exists in a temporal context, 25 and time provides information about concepts such as duration and order. Expectancies are strongly related to temporality because they use information about the past to predict future occurrences. 3 Our sense of temporality is dynamic 26 and subjective, 27 dependent on the individual and his or her circumstances.

Temporality is of particular relevance in the case of expectations relating to Alzheimer's disease, in that the latter may be considered a ‘disease of time’ 28 in which lost memory of events may eventually lead to an amalgamation of the past and the present. For Mary, it appears that the slow perceived progress of her disease mediated a reduction in her appreciation or recognition of the problem. In effect, this time period was of such long duration that no alteration in her expectations occurred while the process was taking place:

My memory has gotten slowly worse, I would say in the last maybe three years… Slowly that a person wouldn't sort of think, you know, there's something wrong. [Mary]

Sense of self‐efficacy

Our model proposes that the first section of the cognitive processing phase, that which simultaneously incorporates senses of time, probability and causality, subsequently leads to a second phase of cognitive processing which itself incorporates two further phenomena: a sense of self‐efficacy, and perception of expected subjective utility. These are less interactive, however, than time, probability and causality. For example, self‐efficacy is a subjective assessment of an individual's ability to perform necessary behaviours in order to achieve future states. Because of the relationship between present behaviour and future events suggested by self‐efficacy, it can be thought of as a type of expectation nested within a larger one: self‐efficacy expectations relate to a person's perceived capability of carrying out a specific behaviour to achieve a wanted result. 29 Self‐efficacy thus serves to guide the level of challenge in the goals that individuals set for themselves; clearly, the higher one's sense of self‐efficacy, the more challenging one's goals are likely to be. 30 Similarly, self‐efficacy influences the effort individuals put into achieving particular goals by affecting their determination to achieve. 31 , 32 Unsurprisingly, past successes increase self‐efficacy expectations while failures diminish them. 32

This medicine is, I have to remember it every day, but I have to take, I've got a little thing where I have my pills in, and I put a thing in for each day, and then I take three in the morning and three in the after…or at night and before I go to bed. And I have been doing that for years. [Mary]

Self‐efficacy, in turn, influences outcome expectations. 23 These are the impressions individuals have about their capability to perform a behaviour in order to produce a certain outcome. In fact, it may be more precise to state that outcome expectations and self‐efficacy enjoy a reciprocal relationship, because self‐efficacy is affected by outcome expectations, and vice versa. 33 For example, if an individual believes he or she has a strong ability to perform a certain behaviour, the expectation of outcome will include the consequences of that behaviour being performed. As an illustration of this, Mary went shopping, realized she'd forgotten to take her list, but successfully persevered with the task because she believed in her ability to ‘work it out’:

There's a lot of things that happen. For instance I went to the store and I forgot to take a list. And I'm thinking now what did I come here for? I sort of walk around the store and all of a sudden it was coming to me what I did come for. [Mary]

Conversely, if the individual doubts his or her ability to perform a behaviour, the outcome expectancy will differ as a result of no behaviour being performed. However, what an individual perceives to be the result of a particular behaviour will affect that person's perceived ability to perform it.

Perceived expected subjective utility

Alongside one's sense of being able to perform behaviours, we suggest, lies one's perception of expected subjective utility, but performance and utility are largely independent constructs: our potential to achieve a state or execute a behaviour need have no correlation with our impression of the value accruing to us as a result of achieving it. Utility refers to the value we think will accrue to us if those events are manifested. Utility denotes actions and stimuli as having properties which may be experienced as either positive (advantageous) or negative (disadvantageous). When making decisions, individuals generally consider a variety of options before selecting a particular one. Not all of these options are demonstrably objective; a great deal of the experience of positive or negative outcomes is subjective. Consequently, ‘subjective expected utility’ represents the anticipated experience of a positive or negative outcome that the individual believes will result from a given action. 34 , 35

Well I'm hoping that it (the medication) will slow it down, forgetfulness down… I'll probably have my memory, you know. Not wonderful, but at least it should be a little better and it'll be better longer. [Mary]

Since expectations of outcome anticipate achieving some utility as a result of behaviour, they direct the content of the behaviour itself.

Goals

We suggest that the final component in the cognitive processing phase of expectation development is the development of goals. Logically, these must be subsequent to the processing of perceived utility, since they are directly influenced by how much they are of value to us. Goals are ideas directed towards future outcomes, which are shaped by past successes and failures. 8 Goals are also affected by expectancies about the consequences of behaviours. 36 To achieve a goal, behaviours must be performed and, obviously, the behaviours most likely to be performed are those with a high perceived probability of helping attain the goal. Goals also hold within them a strong temporal component, in that behaviours that take place in the present are performed in the hope, or with the intention, of achieving a future state of advantage. 37 Because goals take into account a person's ability to perform a certain behaviour, and expectancies develop in relation to these perceived abilities, goals are formed on the basis of perceived self‐efficacy, whereby they contribute to developing expectations. Below, Denise speaks of the action necessary to achieve a desired outcome:

If it was Alzheimer's I had read that there was hopes of holding it but not curing it. And I thought well, if he can keep her at this stage, it's time to see somebody who knows more about it than I do. [Denise]

Expectancy formulation

Expectation of outcome

We suggest that the formulation of an expectation occurs after the processes described above. All of these previous factors combine to determine an expectation of outcome. Outcome expectancies are estimates of behaviours and their consequences, 32 and influence behaviour depending on the perceived consequence. Denise, for example, despite doubts, expected to be able to cope even if Mary's condition deteriorated further:

That's my expectation. That please keep Mary like she is now. Don't let her get any worse. How long I could handle any thing worse, who knows… I'm sure I could do quite a lot more. [Denise]

Interestingly, it has been found that positive outcome expectancies are more influential in inducing behaviours because they are recovered from memory more quickly. 38

Outcome

In our model, we conceptualize outcomes in terms of behaviour, attitude and motivation. Any, or all of these, may be influenced by expectations.

Behaviour

From a health services research point of view, the influence of outcome expectancies on behaviour may be the most compelling aspect of the model. Behaviour is mostly, but not always, purposeful and controlled by forethought. 18 As such, expectations of outcome influence subsequent behaviour. If the outcome expectancy is positive, the behaviour required to attain it is more likely to be engaged in than if the outcome expectancy is negative. In the quotation below, Denise responds to Mary's anxiety which is aroused when Mary's family discuss moving her into ‘a home’:

One (family member) says she could come and we could get you into a home. Well that! I said not yet! That really worried her. She thought that they might be able to move her. And so I went and said that I have power of attorney in money and other matters. So over my dead body! [Denise]

In this case, Denise's outcome expectations associated with Mary going into long‐term care drive her to resist that eventuality. On the other hand, behaviour can be seen to direct expectation, since experiences resulting from behaviour affect future expectations. 39

Attitude

There is a relationship between attitudes and behaviour. The most important understandings a person holds about an object or situation establishes that individual's attitude, or overall feeling, towards the object or situation. 35 Accordingly, while attitudes are clearly influenced by behaviour, 40 they also facilitate choosing a behaviour or course of action. 35 , 41

Motivation

In our model, behaviour and motivation have a mutually influential relationship similar to that existing between behaviour and attitudes. Motivation is an internal process, which activates and guides behaviour. As motivation increases, behaviour becomes more persistent. 42 The corollary of this is that expectations influence behaviour, as different expectations produce differing levels of motivation. 18 In the following example, Denise discusses ideas about Mary entering long‐term care at some future point in time:

I wouldn't put Mary there because it's, there you're on the second floor and there's no chance of getting out and walking around and looking at things. Whereas (small town) has a very open one. And each one has their private rooms… I'm the boss! [Denise]

Denise's assertiveness indicates the strength of her motivation that Mary should not go to a location where her freedom of movement is expected to be limited.

Cognitive processing after outcome

After the actual behaviour is performed, or an attitudinal or motivational shift experienced, we envisage a phase of post‐outcome cognitive processing about what occurred. An important aspect of this processing involves determining the realized utility.

Realized subjective utility

This, in practice, constitutes the satisfaction achieved 43 from the outcome. Satisfaction is the experience which results from the subjective evaluation of the distinction between what actually occurred, and what the individual thinks should have. If the difference between the two is negative, dissatisfaction will result, but if the difference is positive, the result will be positive. 44 The magnitude of the difference between the two is stored as information for future use in similar situations resulting from similar precipitating phenomena.

The doctor thought that some of the Parkinson's medication might help Mary (tremor)… She's been to three or four specialists and they've all said that it's not Parkinson's… (Side effects) were disgusting. (laughs) It was a rough month until she settled down and took her off of it. I talked to (doctor) and he said get rid of it. It didn't do any good. It wasn't helping. [Denise]

Discussion

Our conceptual model differs substantially from that proposed by Thomson and Sunol, 2 particularly in respect of their classification of ‘ideal’, ‘normative’ and ‘unformed’ expectations. In our view, hope is a construct which is entirely independent of expectation. 3 Similarly, we can discover no a priori association between expectation and preference (though we can, obviously, between hope and preference). This differentiation may be important because some authors do conflate these experiences in relation to health care. 45 , 46 In sum, we believe expectations of outcome are, logically, independent of the values which people attach to the substance of those outcomes. While expectations and values are important at clinical and system‐wide levels of health care, and from the perspectives both of lay people and health‐care providers, they are not the same. 47

Olson et al.'s model 3 of expectancy processes bears some similarity to our conceptual model. Both share the elements of belief and experience as antecedents to an expectancy, the notion of probability or degree of certainty, and the constructs of attitude, behaviour and cognitive processing as consequences of an expectancy. Our model emphasizes the elements leading up to an expectancy, whereas Olson et al.'s model has a major emphasis on consequences.

A health expectation can be thought of as a prediction about the consequences of certain health‐related phenomena (behaviours and conditions, both internal and external), on the psychological condition of the body. As such, health expectations may be focused on interventions and treatments, 48 as well as on health status or the presence of disease. Expectations about health can be held by an individual about themselves and their own health status or quality of life, about caregivers of the individual, and about health‐care providers. These expectations are acquired by the same processes and contain the same elements as general expectations. 29 , 31 , 33 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52

Individuals also hold expectations about health services and systems, 47 , 53 which have a major influence on their satisfaction with those services. 44 Our model concurs with the expectation–satisfaction association identified empirically by Larsen and Rootman 54 and utilized by Thomson and Sunol. 2 Extreme unfulfilled expectations result in greater dissatisfaction than average expectations, which when unfulfilled, may yet still result in some degree of satisfaction. 47 Satisfaction studies may be used to assess quality of care and to improve services, 55 but to do so without incorporating an understanding and assessment of the expectations of that care is misleading, because low expectations may be easily satisfied. This problem continues to dog patient satisfaction surveys, confounding their validity and making interpretation uncertain.

Caregivers of patients also hold expectations, which may differ considerably from those of patients themselves. 56 , 57 Family members in particular generally hold (in the Thomson and Sunol terminology) ideal expectations 58 (or hopes). If these are not satisfied, the caregiver may suffer increased stress. 59 Other determinants of caregiver burden include the expectations held about the level of care they must themselves provide. 60 , 61 For example, caregivers’ expectations of their duties have been reported as consisting of taking complete responsibility for care on a daily basis without aid from health‐care professionals at all. In this instance, the only expectations caregivers would hold about the involvement of health‐care professionals would consist of support during the beginning of the caregiving experience. 62 Cultural expectations surrounding the responsibility and value of serving as a familial caregiver have also been shown to be important. 10 , 63 , 64 , 65

Given the importance of the topic, with the exception of research into the influence which patient expectations may have on physician prescribing behaviours, 66 , 67 , 68 it was somewhat surprising to find relatively little research into the basis for a pragmatic conceptualization of a health expectation. This paper utilizes a social‐cognitive approach to redress the balance. We acknowledge that the model is unsupported by empirical evidence, though the illustrative case material presented here implies it has more than hypothetical validity. Future work by our group is designed to examine the model empirically, with the intention of validating its properties (for example, in respect of whether all its elements are always present), developing an instrument for assessing strength and type of expectations of care for Alzheimer's disease (from both lay and professional points of view), and applying that instrument in studies designed to improve our understanding of both the experience of expectation, and its influence on attitude and behavioural outcomes. Such an instrument may draw on research in health promotion and public health research, where methodologies have been developed for measuring the type and strength of expectations associated with, for example, alcohol consumption. 69

These phenomena are important, because it is arguable that more effective and acceptable clinical services are those which are seen to realize a given set of prior expectations among users, as individuals. Furthermore, societally, our expectations of health care, and of health‐care providers, appear to be increasing with time. In the light of this, understanding and measuring health expectations explicitly may become increasingly important components in attempts to make clinical decision‐making relevant to individual patients as well as in priority‐setting, and needs assessment at the health system level. We believe that these may have major implications for socially relevant and ethical resource allocation.

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues in the Dementia‐NET research group, Elizabeth Anderson, Elfrieda Heiden, Seija Kromm and Helen Tam, for their help in the conduct of this study. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on a previous version of the paper. The work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Aging and the Alzheimer Society of Canada.

References

- 1. Evans FJ. The placebo response in pain reduction In: Bonica JJ. (ed.) Advances in Neurology, Vol. 4. New York: Raven Press, 1974: 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thompson AG, Sunol R. Expectations as determinants of patient satisfaction: concepts, theory and evidence. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 1995; 7: 127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olson JM, Roese NJ, Zanna MP. Expectancies In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW. (eds) Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles. New York: The Guilford Press, 1996: 211–238. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hohlstein LA, Smith GT, Atlas JG. An application of expectancy theory to eating disorders: development and validation of measures of eating and dieting expectancies. Psychological Assessment, 1998; 10: 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ajzen I. The social psychology of decision making In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW. (eds) Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles. New York: The Guilford Press, 1996: 297–325. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bolles RC. Reinforcement, expectancy, and learning. Psychological Review, 1972; 79: 394–409. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kirsch I. Conditioning, expectancy, and the placebo effect: comment on Stewart, Williams and Podd. Psychological Bulletin, 2004; 130: 341–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the Self‐regulation of Behaviour. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hirt ER, Jay Lynn S, Payne DG, Krackow E, McCrea SM. Expectancies and memory: inferring the past from what must have been In: Kirsch I. (ed.) How Expectancies Shape Experience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1999: 93–124. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fox K, Levkoff S, Hinton WL. Taking up the caregiver's burden: stories of care for urban African American elders with dementia. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 1999; 23: 501–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Holzberg CS. Ethnicity and aging: anthropological perspectives on more than just the minority elderly. The Gerontologist, 1982; 22: 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldman MS. Expectancy operation: cognitive‐neural models and architectures In: Kirsch I. (ed.) How Expectancies Shape Experience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1999: 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stewart‐Williams S. The placebo puzzle: putting together the pieces. Health Psychology, 2004; 23: 198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alloy LB, Tabachnik N. Assessment of covariation by humans and animals: the joint influence of prior expectancies and current situational information. Psychological Review, 1984; 91: 112–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rotter JB. Social Learning and Clinical Psychology. New York: Prentice‐Hall, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kirsch I. Response expectancy: an introduction In: Kirsch I. (ed.) How Expectancies Shape Experience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1999: 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maddux JE. Expectancies and the social‐cognitive perspective: basic principles, processes, and variables In: Kirsch I. (ed.) How Expectancies Shape Experience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1999: 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. New Jersey: Prentice‐Hall, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kirsch I. Response expectancy as a determinant of experience and behaviour. American Psychologist, 1985; 40: 1189–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kyburg HE, Smokler HF (eds) Studies in Subjective Probability. New York: Wiley and Sons, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burge T. Mind–body causation and explanatory practice In: Heil J, Mele A. (eds) Mental Causation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993: 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 1966; 80: 1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bandura A. Self‐efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: WH Freeman and Company, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldman MS, Brown SA, Christiansen BA. Expectancy theory: thinking about drinking In: Blane HT, Leonard KE. (eds) Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. New York: Guilford Press, 1987: 181–226. [Google Scholar]

- 25. McGrath JE (ed.) The Social Psychology of Time. California: Sage Publications, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Friedman W. About Time: Inventing the Fourth Dimension. MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Michon JA, Jackson JL. Attentional effort and cognitive strategies in the processing of temporal information In: Gibbon J, Allan L. (eds) Timing and Time Perception, Vol. 423. New York: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1984: 298–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leibing A. Flexible hips? On Alzheimer's disease and aging in Brazil. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 2002; 17: 213–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Resnick B, Wehren L, Orwig D. Reliability and validity of the self‐efficacy and outcome expectations for osteoporosis medication adherence scales. Orthopaedic Nursing, 2003; 22: 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Locke EA, Latham GP. A Theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance. New Jersey: Prentice‐Hall, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bandura A. Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies In: Bandura A. (ed.) Self‐efficacy in Changing Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995: 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bandura A. Self‐efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 1977; 84: 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schwarzer R, Fuchs R. Changing risk behaviours and adopting health behaviours: the role of self‐efficacy beliefs In: Bandura A. (ed.) Self‐efficacy in Changing Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995: 259–288. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Edwards W. The theory of decision making. Psychological Bulletin, 1954; 51: 380–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Massachusetts: Addison‐Wesley Publishing Company, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Klein HJ. Further evidence on the relationship between goal setting and expectancy theories. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 1991; 49: 230–257. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jones JM. Cultural differences in temporal perspectives In: McGrath JE. (ed.) The Social Psychology of Time. California: Sage Publications, 1988: 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stacy AW, Widaman KF, Marlatt GA. Expectancy models of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1990; 58: 918–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Goldman MS, Smith GT. Advancing the expectancy concept via the interplay between theory and research. Alcoholism: clinical and experimental research, 2002; 26: 926–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eagly AH, Chaken S. The Psychology of Attitudes. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bem DJ. Beliefs, Attitudes and Human Affairs. Belmont: Brooks/Cole, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Petri HL. Motivation: Theory, Research, and Applications, 3rd edn. Belmont: Wadsworth, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Slavin SL. Microeconomics, 5th edn. New York: McGraw‐Hill, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Campbell A. The concept of well‐being In: Campbell A. (ed.) The Sense of Well‐being in America. New York: McGraw‐Hill, 1981: 25. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Britten N. Patients’ expectations of consultations. BMJ, 2004; 328: 416–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Little P, Dorward M, Warner G, Stephens K, Senior J, Moore M. Importance of patient pressure and perceived medical need for investigations, referral, and prescribing in primary care: nested observational study. BMJ, 2004; 328: 444–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ross CK, Frommelt G, Hazelwood L, Chang RW. The role of expectations in patient satisfaction with medical care. Journal of Health Care Marketing, 1987; 7: 16–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Karlawish JHT, Casarett DJ, James BD, Tenhave T, Clark CM, Asch DA. Why would caregivers not want to treat their relative's Alzheimer's disease? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2003; 51: 1391–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brody H, Brody D. Three perspectives on the placebo response: expectancy, conditioning, and meaning. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine, 2000; 16: 216–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Catanzaro SJ, Mearns J. Mood‐related expectancy, emotional experience, and coping behaviour In: Kirsch I. (ed.) How Expectancies Shape Experience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1999: 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hahn RA. Expectancies of sickness: concept and evidence of the nocebo phenomenon In: Kirsch I. (ed.) How Expectancies Shape Experience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1999: 333–356. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Figaro MK, Russo PM, Allegrante JP. Preferences for arthritis care among urban African Americans: ‘‘I don't want to be cut’’. Health Psychology, 2004; 23: 324–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Uhlmann R, Inui RS, Carter WB. Patient requests and expectations: definitions and clinical implications. Medical Care, 1984; 22: 681–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Larsen DE, Rootman I. Physician role performance and patient satisfaction. Social Science and Medicine, 1976; 10: 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Locker D, Dunt D. Theoretical and methodological issues in sociological studies of consumer satisfaction with medical care. Social Science and Medicine, 1978; 12A: 283–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gwyther LP. Service delivery and utilzation: research directions and clinical implications In: Light E, Niederehe G, Lebowitz BD. (eds) Stress Effects on Family Caregivers of Alzheimer's Patients. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 1994: 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Speice J, Harkness J, Laneri H, et al. Involving family members in cancer care: focus group considerations of patients and oncological providers. Psycho-Oncology, 2000; 9: 101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kilbourne WE, Duffy JA, Duffy M. A comparative study of resident, family, and administrator expectations for service quality in nursing homes. Health Care Management Review, 2001; 26: 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kristjanson LJ, Leis A, Koop PM, Carrière KC, Meuller B. Family members'care expectations, care perceptions, and satisfaction with advanced cancer care: results of a multi‐site pilot study. Journal of Palliative Care, 1997; 13: 5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, Harvath TA. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Research in Nursing & Health, 1990; 13: 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pagel MD, Becker J, Coppel DB. Loss of control, self‐blame, and depression: an investigation of spouse caregivers of Alzheimer's disease patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1985; 94: 169–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wennman‐Larson A, Tishelman C. Advanced home care for cancer at the end of life: a qualitative study of hopes and expectations of family caregivers. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 2002; 16: 240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Donorfio LM, Sheehan NW. Relationship dynamics between aging mothers and caregiving daughters: filial expectations and responsibilities. Journal of Adult Development, 2001; 8: 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ikels C. Constructing and deconstructing the self: dementia in China. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 2002; 17: 233–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Aranda MP, Knight BG. The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: a sociocultural review and analysis. The Gerontologist, 1997; 37: 342–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schwartz RK, Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Physician motivations for non‐scientific drug prescribing. Social Science and Medicine, 1989; 28: 577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Webb S, Lloyd M. Prescribing and referral in general practice: a study of patients’ expectations and doctors’ actions. British Journal of General Practice, 1994; 44: 165–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Britten N, Ukoumunne OC, Boulton MG. Patients’ attitudes to medicines and expectations for prescriptions. Health Expectations, 2002; 5: 256–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Southwicke L, Steele C, Marlatt A, Lindell M. Alcohol‐related expectancies: defined by phase of intoxication and drinking experience. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1981; 49: 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]