Abstract

Background ‘Continuity of care’ is an important aspect of quality. However, definitions are broad and existing models of continuity are not well grounded in empirical data.

Objective To identify patients’ experiences and values with respect to continuity in diabetes care.

Methods In‐depth semi‐structured interviews with 25 type 2 diabetic patients from 14 general practices in two inner London boroughs. Interviews were transcribed and responses analysed thematically and grouped into dimensions of continuity of care.

Results Patients’ accounts identified aspects of care they valued that were consistent with four dimensions of experienced continuity of care. These were receiving regular reviews with clinical testing and provision of advice over time (longitudinal continuity); having a relationship with a usual care provider who knew and understood them, was concerned and interested, and took time to listen and explain (relational continuity); flexibility of service provision in response to changing needs or situations (flexible continuity); and consistency and co‐ordination between different members of staff, and between hospital and general practice or community settings (team and cross‐boundary continuity). Problems of a lack of experienced continuity mainly occurred at transitions between sites of care, between providers, or with major changes in patients’ needs.

Conclusions The study develops a patient‐based framework for assessing continuity of care in chronic disease management and identifies key transition points with problems of lack of continuity. It is important that service ‘redesign’ and developments in vertically integrated services for chronic disease management take account of impacts on patients’ experience of continuity of care.

Keywords: continuity of care, general practice, patient perspective, patient views, type 2 diabetes mellitus

Introduction

Continuity of care is considered to be an important characteristic of high quality health care but it is not often evaluated explicitly because of the lack of an agreed definition and suitable measurement tools. 1 However, policy decisions affecting the organization and delivery of health services may often have important but unintended consequences for continuity of care. 2 , 3

‘Continuity of care’ is a wide‐ranging concept, which encompasses several different aspects of health care, whose significance may vary in different settings. In primary care, emphasis is given to the on‐going relationship between the practitioner and his/her patients. 2 , 4 This has traditionally formed a central characteristic of care provided by General Practitioners (GPs) in the UK and is illustrated by the American Academy of Family Physician's (AAFP) definition of continuity of care ‘as the process by which the patient and the physician are co‐operatively involved in on‐going health‐care management towards the goal of high quality, cost‐effective medical care’. 5 However, the move towards primary care teams and a greater development of vertically integrated systems for chronic disease management has emphasized the need for the effective co‐ordination of care between different team members and between agencies to provide a ‘seamless’ service that meets the goals of efficiency, effectiveness and responsiveness to patients’ needs. 1 , 2

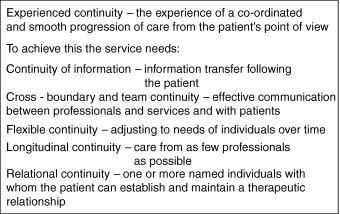

In their recent review, Haggerty et al. 1 suggested that there are three types of continuity of care, i.e. relational continuity characterized by ‘an on‐going therapeutic relationship between a patient and one or more providers’; management continuity, characterized by a consistent approach to the clinical management of a health condition that is responsive to patients’ changing needs, and informational continuity in which clinical information is used to make current care appropriate for each individual. However, there is an important distinction between continuity in the delivery of care and continuity in the experience of care. Continuity in the delivery of care encompasses aspects, such as management continuity or informational continuity, which are more relevant to the providers of care including health professionals and health‐care organizations. Continuity in the experience of care is a complementary concept that encompasses the concerns, values and experiences of service users, including patients, families and carers. This was recognized by Freeman et al. 2 who proposed that ‘experienced continuity’ should be recognized as one of the dimensions of continuity of care. Freeman et al. 2 drew on earlier work by Bacharach 6 and Hennen 7 to develop a model of continuity of care which comprised six dimensions of the delivery and experience of care (Box 1). This will be referred to as Freeman et al.’s 2 model.

Figure Box 1.

Freeman's model of continuity of care.

Although considerable emphasis is now given to the assessment of quality of care through eliciting the views and experiences of patients, present models of continuity of care are not well grounded in empirical data 2 . This raises the question of how well patients’ experiences and values with respect to continuity of care fit with proposed models of continuity of care. This information is needed both to establish a valid conceptual framework and to generate items from which appropriate patient‐based measures can be developed.

This study focuses on patients with type 2 diabetes, a common condition 8 that typifies many of the generic problems of chronic illness. The management of diabetes requires contributions from staff with different types of training in primary care, as well as input from specialist hospital‐based services for treatment of complications, which may arise at any time. The best way of integrating these services is debated. 9 Service organization currently varies in different places and may involve primarily GP care, primarily hospital care and various models of care shared between general practice and hospitals. 10 We therefore examined the values and experiences of diabetic patients receiving care in a range of settings, with the aim of identifying items that comprise different dimensions of continuity of care as a basis both for further qualitative assessment of patients’ experiences of continuity of care and developing a measure of continuity that is grounded in patients’ experiences.

Methods

A qualitative study involving semi‐structured interviews 11 was conducted with type 2 diabetes patients in two adjoining inner London primary care trusts (PCTs), i.e. Lambeth and Southwark. Approval was given by the Research Ethics Committee of Guy's Hospital. Respondents gave written informed consent to participation.

Recruitment of patients

Forty‐one general practices in the two PCTS were sent letters inviting them to take part in the study. Fourteen practices agreed to participate and provided us with their list of patients recorded as having diabetes. We used these lists with the Diabetes Integrated Shared Care (DISC) database 12 to identify patients’ diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. We selected a purposive sample of 30 patients to include the main ethnic minority groups (Black Caribbean, Black African and South Asian). Letters and an information sheet were sent to patients inviting them to take part in the study. The initial response was low (five of 30) and follow‐up telephone calls were therefore made to each patient 3 weeks after the initial mail out.

Interviews

Semi‐structured interviews were conducted between January and June 2003. Interviews were held in patients’ homes and lasted between 30 and 120 min, with the majority lasting about an hour. All interviews were tape‐recorded with the respondents’ permission. These interviews examined patients’ experiences and values regarding their diabetes care quite broadly, rather than aiming at this stage to operationalize a particular measure of continuity and asking questions specifically framed in these terms. Initially the conversations began by asking general open‐ended questions concerning the respondent's diabetes, diagnosis and the type of care they were currently receiving. Other questions and probes were loosely based on a topic guide. This had been informed by the continuity literature and by four exploratory interviews that took the form of fairly open discussions of respondents’ diabetes care to identify issues of importance for them. The continuity literature provided a broad framework for developing the interviews, as without this we would have difficulty in knowing what we were investigating, especially given that ‘continuity of care’ is not currently an everyday lay term. For this reason respondents were not specifically asked about the meaning of ‘continuity of care’ and they did not mention the term despite the information sent with invitations to participate describing the study as concerned with continuity of care.

The main topics covered by the guide were: the circumstances surrounding the respondents diagnosis and type of care provided, communication with staff, patient–provider relationships including the advantages/disadvantages of seeing a usual provider, the experience of care in general practice and hospital settings, service flexibility and meeting patients needs. Probe questions were used to clarify responses and elicit greater detail, especially in terms of aspects of care that respondents perceived worked well or badly for them. Respondents were also encouraged to discuss issues and directions of thought that went beyond this framework.

Analysis

All interviews were tape‐recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were anonymized and each read by the researcher (NS) and one other author. The transcripts were entered into qsr n6, a computer software package for the management of qualitative data. Analysis initially involved coding segments of transcripts that described patients’ views and experiences of their diabetes care. Major categories included type of care (initial and current care), tests and checks (reviews, weight, blood sugars, BP, cholesterol), communication with regular provider and with other staff (e.g. listens, knows me, approachable, no interest, too rushed), service provision and co‐ordination (e.g. delays, conflicting advice, difficulties in an emergency). We then mapped patients’ coded experiences of diabetes care to Freeman et al.’s dimensions of continuity. This model was selected as forming the product of a synthesis of previous approaches to continuity of care and emphasizing the primary–secondary interface. 2 However, whereas Freeman et al. 2 identified a broad category of ‘patient experiences’ and subdivided aspects of professionals’ experience of delivering continuity of care into longitudinal, flexible, relational, team and cross‐boundary and informational continuity, in our study most of these provider‐based dimensions also appeared to be applicable to the patient data. The main exception was informational continuity that refers to efficient systems of information transfer, as patients had little knowledge of these processes, although they commented on their experiences of problems of communication. If their statement referred to communication between professionals and across care boundaries it was allocated to team and cross‐boundary continuity, whereas communication with their main provider and their ability to build and sustain a relationship was allocated to relational continuity. The mapping of items involved discussion of some individual items by the three authors to reach a consensus regarding their allocation to specific dimensions of continuity. In a few cases it was difficult to allocate data items between the continuity categories because dimensions are interrelated and some experiences illustrated several dimensions simultaneously. In these cases our emphasis in allocation to a specific dimension involved considering the broader context in which the item occurred. For example, the number of times a patient saw a regular provider was allocated to longitudinal rather than relational continuity to take account of the temporal dimension, and the need to be seen quickly at hospital for complications was classified as flexible continuity which was defined as the speed of adapting to specific needs rather than cross‐boundary continuity which refers to the co‐ordination of services.

Findings

Twenty‐five diabetic patients (who spoke English) were interviewed, and all had type 2 diabetes (see Table 1). They were living in a relatively deprived inner city area covering two inner London PCTs which have young, mobile and ethnically diverse populations and high levels of deprivation with Jarman Underpriviledged Area (UPA) scores of 48 and 56, respectively, compared with a UPA score of 0 for England and Wales. 13 Ten patients were receiving GP care, 11 were receiving shared care and four patients only received diabetes care from hospital diabetic clinics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | Numbers |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 17 |

| Female | 8 |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 17 |

| Black | 4 |

| Indian | 1 |

| Other | 3 |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (range) | 67 (41–86) |

| Household component | |

| Live alone | 14 |

| Live with other | 11 |

| Home ownership | |

| Owner occupied | 14 |

| Rented | 11 |

| Years diagnosed with diabetes | |

| Mean (range) | 7 (1–27) |

| Type of care | |

| GP | 10 |

| Hospital | 4 |

| Shared care | 11 |

The types of patient experience classified within the four categories of longitudinal, relational, team and cross‐boundary continuity are described below and the key components of each dimension based on this interview data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of patient‐derived themes for each dimension of experienced continuity of care

| Dimension of experienced continuity of care | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal | Relational | Flexible | Team and cross‐boundary |

| Regular consultations | Identifies usual doctor/nurse | Making and changing appointments | Appropriate co‐ordination of services |

| Receives appointment letters | Usual doctor/nurse knows and understands me | Speaking to a usual doctor/nurse when needed | All staff know medical history and treatment |

| Regular tests and checks | Doctor/nurse listens, enough time to talk | Getting advice in an emergency | Staff communicate with each other |

| Regularly sees usual doctor/nurse | Can talk about anything, confiding | Staff give consistent advice | |

| Doctor/nurse concerned and interested | |||

| Mutual trust and confidence | |||

| Doctor/nurse explains things | |||

Dimensions of continuity of care

Experienced longitudinal continuity

Patients described the on‐going care they received from the time of diagnosis or during episodes of illness. This included making opportunistic visits to their doctor or attending regular check‐ups where a number of clinical tests were carried out. This on‐going care corresponds with the notion of longitudinal continuity:

‘…at the practice – on a regular basis, every couple of months I go there, they check everything, my blood, blood pressure … and every so often, I think it's every year, she checks my feet with a … it's like a little prodder – but she only does that once every year really (PA3 – Shared care)’.

Respondents occasionally referred to the importance of continuity of care over time in terms of their concerns about the lack of such care:

‘I used to go to my doctor every 6 months, he would check everything and they would give me appointment date for my next check up but he's left now and there is someone else doing it. I haven't received anything, no one has bothered. I have to go up there myself. It's really gone down hill (PA5 – GP care)’.

A higher intensity of visits occurred in the early months after diagnosis, during episodes of illness or when patients were experiencing difficulties in managing their diabetes at home.

During the initial months after diagnosis, consultations with a consistent, usual care provider were particularly valued because they helped patients increase their understanding of the condition and its treatment. Longitudinal continuity was also viewed as important for delivering personally tailored advice.

‘When ever I go there she checks my diary and gives me tips on what I should eat. If I have problems with my machine she helps me (PA4 – Shared care)’.

Experienced longitudinal continuity can be viewed as a necessary condition for establishing relational continuity:

‘Nurse K. She's the only one I see for diabetes. I used to see my own doctor but she said ‘‘I think we'll put you with nurse K because nurse K deals with diabetes all day’’. Everybody who has got diabetes goes to see her. So now she does all the test and checks (PA8 – GP care)’.

Experienced relational continuity

Patients’ accounts focused on their perceptions of professionals caring for them and their relationships with those they saw on a regular basis. Patients valued an on‐going relationship with a usual care provider (generally a doctor or nurse), as this provider would know about their diabetes and not need reminding:

‘Personally I think it's a good thing to see the same person, they know your problems, if you've had a problem before it will be fresh in their minds … when I've seen different staff they don't know what's going on, you have to constantly remind them (PA2 – Shared care)’.

Problems of doctors’ lack of familiarity with the patient were more frequent in the hospital clinic setting:

‘sometimes when I go to the doctor I find that I have got to remind them or tell them what has happened. Because I only go once a year and you don't always see they same person, well I'm certain I won't see the same person so they are not likely to know what's happened because they look to me like they don't know (PA11 – Hospital care)’.

An essential feature for patients is that their usual care provider knows not only about their diabetes but also understands them as a person:

‘I have a good relationship with my doctor, we understand each other … I've been with him for the last 30 years, he knows me and that's not just my diabetes, that's everything (PA6 – GP care)’.

Lack of this personal relationship meant that patients often felt less involved in the consultation and less satisfied with their care:

‘Maybe it's mistrust on my part. Well apart from Nurse T now, I don't know the doctor that I'm seeing. I don't know how interested he is in diabetes. The one or two occasions that I have seen him, he hasn't got the chance to get to know me, I know that. But I did just sort of get the feeling that it was a question of getting me in and out as quickly as possible. I didn't feel involved, I'm not sure that he will be as thorough (PA6 – Shared care)’.

Patients whose care providers knew them well also had more confidence in them and trusted their advice:

‘I knew my doctor for a long time, so when he explained things to me, he gave me confidence that I would be fine so long as I looked after myself, you know. I must admit I was frightened but he talked to me, spent a lot of time talking to me, until I understood and felt better… (PA2 – Shared care)’.

A further theme was the importance of the care provider listening and giving enough time to talk:

‘Dr C never rushes you. He rushes about, but if you've got something to say, he will listen to you and he will ask you questions. And he'll talk to you and, yes he's alright. As I say, he rushes about himself, but no, he doesn't rush you (PA – Shared care)’.

Patients who knew their care provider well were also more able to discuss or disclose sensitive issues related both to potentially embarrassing situations and to patients' fears and worries about diabetes:

‘Things that I maybe would not talk with you I talk with him. Things I would not talk with anybody even the nurse I would not discuss with her I would discuss with him so he knows my actual psychological feeling about diabetes and what implications or what feelings I have about it (PA3 – GP care)’.

Another important aspect of their personal relationship with a doctor or nurse was their ability and willingness to listen and to explain things to patients:

‘She listens to you and she explains things and she doesn't rush in and out. She's a very good doctor. The nurse is very good. I feel I can sit and talk to her more cos I've known her longer. The doctor's good, and as I've said to you, she listens and she explains things to you (PA15 – Shared care)’.

Thus, relational continuity involved not only the degree to which professionals were familiar with their patients but also the extent to which they knew the patient's medical history and treatment plans, were prepared to listen, able to explain medical procedures and tests clearly, inspired confidence and involved patients in decisions about their treatment. Seeing a usual provider was important to patients during the early months after diagnosis, particularly for those experiencing complications and difficulties in accepting and managing their diabetes. Usual providers were trusted and perceived to be more knowledgeable compared with other professionals.

Experienced flexible continuity

An important feature of continuity of care identified by patients was the ability to get appropriate advice when required. As patients’ care needs varied and changed over time it was important to them that staff responded quickly. This can be related to the concept of flexible continuity, 2 , 6 which requires services and staff to be flexible and adjust to the needs of the individual over time. This may include the patient being able to consult with a chosen professional:

‘The nurse … always makes time for me. If I phone in the she will always call me back on the same day. I have been able to see her when I've needed to (PA3 – Shared care)’.

Flexible continuity was also manifest in making and changing appointments in response to changing needs and circumstances:

‘They're very good here you know, whenever I need to see the doctor I can just phone up and get a appointment when you want, you don't have to wait long and they ask you, you know, what's it about so if you need more time then they will book you a double appointment (PA13 – GP care)’.

In contrast, patients often described hospitals as having less flexibility in appointments:

‘You don't make appointments, they send you a letter with an appointment date … there's been one time when I couldn't make it and I phoned and cancelled. Then I had to wait over 6 months before they gave me another appointment, it was ridiculous. So now I try and do me best not to cancel because it takes them so long to book you in again (P14 – Hospital care)’.

Flexible continuity was also evident in the response to unexpected situations:

‘I nearly ran out of some pills, so I struggled up there and I got the pills … I must say when they deal with you they are quick (PA8 – Shared care)’.

and in response to emergencies:

‘If I have any problems I can call them at the hospital, if its not so serious they will give the advice on the phone but if its serious they will get the ambulance to take me up there (PA12 – Hospital care)’.

Most patients experienced some lack of flexible continuity, particularly long waiting times, problems and delays in getting appointments and seeing staff of their choice. However, patients who had a good relationship with their provider(s) were more willing to adapt to these difficulties, attributing such discontinuities to organizational problems.

Experienced team and cross‐boundary continuity

Patients' experiences and perceptions of how well their overall care was co‐ordinated relates to the notion of experienced team and cross‐boundary continuity. This partly involved the co‐ordination of care between professionals in the same setting:

‘They talk to each other, sometimes the doctor will come in while I'm seeing the nurse. Sometimes the nurse will go in and talk to the doctor to check on something, it may be about my results or medication. Something like that (PA2 – Shared care)’.

It also referred to care provided by health professionals in different organizational settings:

‘As I say, they sorted it out for the district nurses to come every day and that, check up and that carry on. If I had to go up to get a check up at the surgery department, they would have a car organised for me to take me up there and bring me back (PA19 – Shared care)’.

Team and cross‐boundary communication are underpinned by the flow of clinical information. This featured in patient's accounts in terms of information available to their provider:

‘I feel they know me, they know what's going on with my diabetes because sometimes when I've been to the hospital my doctor tells me that he's received the results, he goes through them with me, what they have said and what should be done (PA4 – Shared care)’.

Other patients identified problems relating to this information transfer:

‘Just recently I have had to change doctors because the doctor that I have been seeing has retired. When I went to the new practice and registered and went to see the nurse, they told me they didn't have any information on me and my medical records hadn't turned up (PA15 – Shared care)’.

However, some patients acknowledged that they were not able to judge whether clinical information was available:

‘They must talk to each otherwise how would they organise the services? They all say the same thing, I mean they all have their own area but when they have given me advice it has been the same (PA23 – Hospital care)’.

Patients’ accounts included relatively little material relating to the organization and co‐ordination of their care as this occurred ‘behind the scenes’ and their involvement was unnecessary. However, some patients reported delays in seeing specialist staff and receiving treatment, and problems arising because of information being missing.

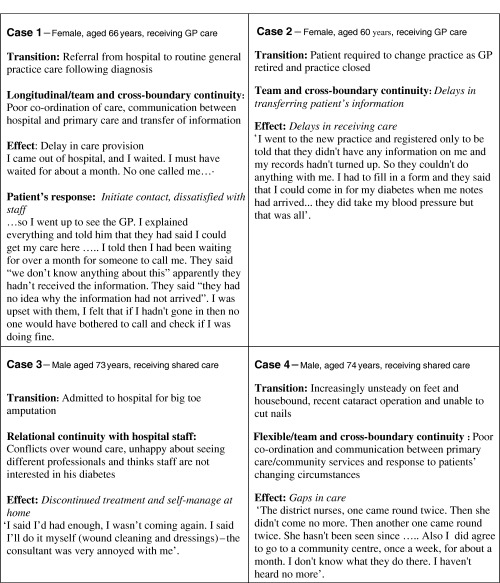

Risks of lack of continuity

Lack of continuity could occur at any point in the patients’ diabetes, although particular risks occurred at transition points. Three of these related to changes in patients’ condition and needs for services: transfer from hospital to routine general practice care following diagnosis; referral to hospital following an episode of illness and changes in patients’ own health state necessitating changes in services provided on a regular basis with requirements for flexible and team and cross‐boundary continuity. A further transition point was a result of changes in services due to provider retirement, holidays or leave, etc. These transitions, and their impacts are illustrated by four brief case studies derived from respondents’ accounts (Box 2). The outcomes for patients of a lack of experienced continuity involved gaps and delays in service provision, lack of information and problems of communication. Patients’ responses to their perception of a serious lack of experienced continuity of care were sometimes to seek alternative care and advice, non‐compliance with advice or treatment, or withdrawal from formal services and attempting to monitor and manage their condition themselves.

Figure Box 2.

Case studies: problems of continuity of care.

Discussion

Our study is one of the first to provide empirical support for a model of continuity of care drawn from patients’ experiences. Using patients’ accounts to understand the concept of continuity was difficult because patients rarely used the term ‘continuity of care’. Determining which dimensions of continuity were exemplified by an experience was also sometimes problematic because dimensions are interrelated and some experiences illustrated several different dimensions simultaneously. However, there was considerable consistency in patients’ accounts of processes of care that were viewed positively or whose lack were commented on negatively.

In general, our data show that for patients with a chronic illness‐like type 2 diabetes mellitus, the classification proposed by Freeman et al. 2 provides a good fit to their experiences and values with respect to on‐going care. An exception is the informational dimension that was excluded because our data showed that patients had little or no knowledge about information transfer in terms of the systems used by staff to share information and made relatively few comments on this aspect. In addition, whereas Freeman et al.’s 2 dimension of team and cross‐boundary continuity is defined in terms of ‘effective communication between professionals and services and with patients’, our findings suggest that this dimension should be understood from the patient's perspective in terms of how well patients perceive their care is organized and co‐ordinated, whether they received consistent information, and whether staff were knowledgeable about their medical history and shared an agreed plan of treatment.

Our approach was to map qualitative data onto an existing scheme, modifying this scheme as necessary, rather than engage in theory building. Freeman et al.’s model 2 was derived from a synthesis of prior studies and it therefore seemed appropriate to assess whether it was feasible to build on this framework, especially with the need to move beyond conceptual development and achieve a greater understanding of relationships between continuity and outcomes. We recognize that the process of categorization risks losing data, although the present study describes the framework items in detail. There is also some overlap between aspects of continuity of care, particularly relational continuity and other measures of patients’ views of services such as the General Practice Assessment Questionnaire (GPAQ) 14 and the NHS surveys of general practice and hospital outpatients. 15 However, our study provides a broad framework and candidate items that may be employed to monitor and evaluate the various aspects and dimensions of continuity of care.

Key themes associated with patients’ experiences of continuity of care are summarized in Table 2. Longitudinal continuity has been evaluated in several ways including the length of time a patient has known the doctor, 16 or the number of different professionals consulted. 17 Our data from patients with diabetes suggest that longitudinal continuity extends beyond simple numerical indicators. It may be measured in terms of the frequency and regularity of consultations to review diabetes (‘check‐ups’) together with the associated monitoring and testing, and the giving and receiving of individualized advice, often from one professional with identifiable responsibility for the patients’ diabetes. This sets the scene for the development of relational continuity and the delivery of personal care. 18 It was clear that these diabetic patients placed considerable value on relational continuity in terms of sustaining a relationship with a main provider. They regarded the usual providers whom they see regularly for diabetes as knowing about their medical history, understanding them as individuals, taking time to listen to what they have to say, explaining things and involving them in decisions. Patients often regarded their usual providers as having superior technical abilities, and were more inclined to confide in them, trust them and follow their advice, with a lack of relational continuity being most likely to lead to disengagement with care. These aspects of relational continuity are broadly consistent with those reported in other studies, 2 , 18 , 19 with the importance patients assign to relational continuity being greater for chronic or more serious conditions than for acute problems or for ‘embarrassing’ complaints. 18 For diabetes both the possibility of speaking to a usual provider and timely access were valued but it was not possible to clarify situations under which one or the other might be preferred.

The other dimension particularly valued by patients was team and cross‐boundary continuity. Risks of deficiencies in this area are increasing as care is undertaken across the primary–secondary interface and in some cases led to the reporting of considerable delays in service provision, gaps in services and patient dissatisfaction.

Our data suggest that patients generally have less favourable experiences with respect to continuity of diabetes care provided in specialist hospital‐based settings when compared with general practice‐based care. Patients generally make less frequent visits to hospital clinics, are less likely to see the same professional at successive visits and hospital services tended to be less flexible in terms of rearranging appointments in response to changing needs. This requires confirmation in quantitative data from larger samples. However, these observations raise questions concerning whether longitudinal, relational and flexible continuity are equally important in more than one setting when care is shared between settings, although efforts to improve patients’ experiences of continuity of the care delivered from specialist settings are desirable. This requires attention to issues of service organization and delivery, ‘Front stage continuity, at the patient interface, must reflect behind the scenes continuity at the system level’. 20

There is evidence that continuity of care is associated with greater patient satisfaction, 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 with some patients responding to a lack of experienced continuity by non‐adherence or withdrawal from care. 25 More attention should therefore be given to these aspects of patients’ experience in designing services for chronic illnesses like diabetes and to the monitoring of transition points. There is also a need for data on the relationship between continuity of care and clinical outcomes. Respondents in our study, who were predominately of older age and from fairly disadvantaged backgrounds, did not engage in sophisticated discussion of the relationships between continuity and specific aspects of diabetes management such as glycaemic control, management of blood pressure (BP), use of medication, etc., and these aspects were not generally probed. A key trial of patient‐centred care of diabetes in general practice reported better communication and greater treatment satisfaction among the intervention group trained in patient‐centred care, but body mass index was significantly higher as were triglyceride concentrations, whereas knowledge scores were lower and differences in lifestyle and glycaemic control were not significantly different from the usual care group. 26 The poorer clinical outcomes in the intervention group have not been fully accounted for, although questions have been raised regarding the effects of the training package on doctors actual behaviours, 27 and the possible effects in the intervention group of adherence to prescribed hypoglycaemic drugs that are known to increase weight gain. 28 , 29 However, as Kinmonth et al. warn, achievement of the personal aspects of care should not result in a loss of focus on disease management. 26 More generally, continuity of care is now identified as one of several outcomes of care and benchmarks of quality rather than a process variable, 30 while there is evidence that patients assign priority to both aspects in terms of the ‘humaneness’ of care and ‘competence/accuracy’. 31 Continuity of care may also contribute to efficiency and lower health‐care costs through fewer tests and referrals. 30 , 32

Issues raised by market‐based models of primary care include the trade‐off that may be required between personal and longitudinal relationship with a single provider and accessibility of health care. 33 Preferences may vary for different groups of patients, with older people with chronic conditions placing particular value on continuity of care from professionals they know, whereas younger patients and those with urgent needs may more readily trade continuity for faster access. 31 It has also been found that some patients report the feeling of personal doctoring after only a few consultations with a new general practitioner, whereas others may not attained this after several years of contact with the same doctor. 34

The framework we have developed provides an assessment of different dimensions of continuity that is applicable not only to the relationship between an individual patient and their family practitioner but also to continuity of care provided by teams and across care settings. The items identified may serve as a topic list for qualitative interviews to provide a detailed account of patients’ experiences of care and pathways through services for chronic disease management and form the basis for a formal measure that will allow direct assessment of the relationship between continuity of care, patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes in different settings and populations. Assessment of these aspects of patients’ experience are likely to be of particular value in relation to the current approaches to ‘system redesign’ and developments in vertically integrated services for chronic disease management.

Declarations

-

•

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Guy's Hospital, London.

-

•

The UK NHS R&D Programme in Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) funded the study.

-

•

None of the authors is aware of any conflict of interest with respect to this paper.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the UK National Health Service Research and Development Programme in Service Delivery and Organisation.

References

- 1. Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. British Medical Journal, 2003; 327: 1219–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Freeman G, Shepperd S, Robinson I, Ehrich K, Richards S. Report of a Scoping Exercise for the National Co‐ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO). London, UK: NCCSDO, 2000. Available at: http://www.sdo.lshtm.ac.uk/pdf/coc_scopingexercise_report.pdf, accessed on 30 January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Humphrey C, Ehrich K, Kelly B, Sandall J, Redfern S, Morgan M, Guest D. Human resource policies and continuity of care. Journal of Health Organisation and Management, 2002; 17: 102–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Freeman GK, Olesen F, Hjortdahl P. Continuity of care: an essential element of modern general practice? Family Practice, 2003; 20: 623–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Academy of Family Physicians . Continuity of Care, Definition of American Academy of Family Physicians. Washington, DC, USA: AAFP, 2005. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/x6694.xml, accessed on 15th February 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bacharach LL. Continuity of care for chronic mental patients: a conceptual analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 1981; 138: 1449–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hennen BK. Continuity of care in family practice: Part 1. Dimensions of continuity. The Journal of Family Practice, 1975; 2: 371–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. International Diabetes Federation . Diabetes Atlas, 2nd edn. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Griffin S. Diabetes care in general practice: meta‐analysis of randomised control trials. British Medical Journal, 1998; 317: 390–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. UK Audit Commission . Testing Times: a Review of Diabetes Services in England. London, UK: Audit Commission, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murphy E, Dingwall R, Greatbach D, Parker S, Watson P. Qualitative research methods in health technology assessment: a review of the literature. Health Technology Assessment, 1998; 2: 1–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mohiddin A, Carey S, Costa D, Jones R. Integrated care for people with diabetes in south London. Diabetes and Primary Care, 2003; 5: 174–178. [Google Scholar]

- 13. National PCT Database . Jarman Underprivileged Area (UPA) Scores. Available at: http://www.primary‐care‐db.org.uk/indexmenu/jarman_desc.html, accessed on 30 January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14. General Practice Assessment Questionnaire (GPAQ). Available at: http://www.gpaq.info. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Healthcare Commission/Picker Institute. NHS Surveys Document Database . Available at: http://www.nhssurveys.org/categories.asp? Accessed on 30 January 2006.

- 16. Parchman ML, Burge SK. The patient‐physician relationship, primary care attributes, and preventative services. Family Medicine, 2004; 36: 22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bice TW, Boxerman SB. A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Medical Care, 1977; 15: 347–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tarrant C, Windridge K, Boulton M, Baker R, Freeman G. Qualitative study of the meaning of personal care in general practice. British Medical Journal, 2003; 326: 1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schers H, Webster S, Van Den HH, Avery A, Grol R, Van Den BW. Continuity of care in general practice: a survey of patients’ views. British Journal of General Practice, 2002; 52: 459–462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krogstad AU, Hofoss D, Hjortdahl P. Continuity of hospital care: beyond the question of personal contact. BMJ, 2002; 324: 36–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mechanic D. In my chosen doctor I trust. British Medical Journal, 2004; 329: 1418–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arborelius E, Bremberg S. What does a human relationship with the doctor mean? Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 1992; 10: 163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schers H, Van Den Hoogen H, Bor H, Grol R, Van Den Bosch W. Familiarity with a GP and patients’ evaluations of care. A cross‐sectional study. Family Practice, 2005; 22: 15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saultz JW, Alledawi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Annals of Family Medicine, 2004; 2: 445–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dietrich AJ, Marton KI. Does continuous care from a physician make a difference? Journal of Family Practice, 1982; 15: 929–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kinmonth AL, Woodcock A, Griffin S, Spiegal N, Campbell MJ. Randomised controlled trial of patient‐centred care of diabetes in general practice: impact on current well‐being and future disease risk. BMJ, 1998; 317: 1202–1208 (reply). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coleman T. Study failed to measure patient centredness of GPs consulting behaviour. BMJ, 1998; 317: 1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hand C. Might differences in prescribing explain some of the findings? BMJ, 1998; 317: 1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kinmonth AL, Woodcock A, Griffin S, Spiegal N, Campbell MJ. Authors’ reply. BMJ, 1998; 317: 1209–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Christakis DA. Continuity of care: process or outcome? Annals of Family Medicine, 2003; 1: 131–133 (editorial). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Coulter A. The NHS revolution: health care in the market place. What do patients and the public want from primary care? BMJ, 2005; 331: 1199–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saultz JW, Lochner J. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Annals of Family Medicine, 2005; 3: 159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marshall M, Wilson T. The NHS revolution: health care in the marketplace. Competition in general practice. BMJ, 2005; 331: 1196–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hjortdahl P, Laerum E. Continuity of care in general practice: effect on patient satisfaction. BMJ, 1992; 304: 1287–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]