Abstract

Objectives The Antenatal Screening Web Resource (AnSWeR) was designed to support informed prenatal testing choices by providing balanced information about disability, based on the testimonies of disabled people and their families. We were commissioned by the developers to independently evaluate the website. This paper focused on how participants evaluated AnSWeR in terms of providing balanced information.

Setting West Yorkshire.

Participants A total of 69 people were drawn from three groups: health professionals, people with personal experience of tested‐for conditions (Down’s syndrome, cystic fibrosis and spina bifida) and people representing potential users of the resource.

Method Data were collected via focus groups and electronic questionnaires.

Results Participants believed that information about the experience of living with the tested‐for conditions and terminating a pregnancy for the conditions were important to support informed antenatal testing and termination decisions. However, there were differences in opinion about whether the information about the tested‐for conditions was balanced or not. Some people felt that the inclusion of photographs of people with the tested‐for conditions introduced biases (both positive and negative). Many participants were also of the opinion that AnSWeR presented insufficient information on termination of an affected pregnancy to support informed choice.

Conclusion This study highlighted the difficulty of designing ‘balanced’ information about tested‐for conditions and a lack of methodology for doing so. It is suggested that AnSWeR currently provides a counterbalance to other websites that focus on the medical aspects of disability. Its aim to provide ‘balanced’ information would be aided by increasing the number and range of case studies available on the website.

Keywords: choice, disablity, information, prenatal testing, termination

Introduction

Advances in technology mean that prenatal tests are now available for a growing number of congenital conditions. Guidelines recommend that people should make informed autonomous choices about whether or not to undergo prenatal testing and should receive all the decision‐relevant information presented in a non‐directive fashion. 1 , 2 , 3 Providing balanced, detailed information about each condition to be tested for raises a number of practical issues. Time restrictions within the clinical setting make it unrealistic to expect health professionals to provide this information personally and not all health professionals who come into contact with pregnant women are best placed to provide information about disabling conditions. Due to knowledge and time constraints, practitioners may rely on ‘medical textbook’ information and on the use of information leaflets. 4

Material contained in prenatal screening information leaflets has also been subject to criticism. 5 One study evaluating 80 leaflets provided in the UK to pregnant women prior to serum screening found that one‐third contained no descriptive information about Down’s syndrome. 6 In the remaining two‐thirds, information about the condition was overwhelmingly medico‐clinical in nature. Similar findings were reported in a study of leaflets for cystic fibrosis screening. 7 While there is an agreement that decision‐relevant information includes material about the tested‐for conditions, there is little guidance for practitioners on how to present such information in a balanced way. 4 , 6

Very little research has looked at patient preferences for information about tested‐for conditions, although a number of studies demonstrate that women often feel there is too little in this respect. 8 Studies from the area of genetic counselling suggest that patients may have different information priorities than their counsellors. For example, a study investigating information recall in genetic counselling found that ‘patients more frequently judged information about family implications of the condition to be important than did counsellors’, while ‘counsellors more frequently judged information about test, diagnosis and prognosis to be important than did patients’. 9

In recent years, a number of websites have been developed to provide information about antenatal screening. For example, MedicDirect (http://www.medicdirect.co.uk/tests/default.ihtml?id=116&step=2) provides a guide to tests during pregnancy, and DIPEx (http://www.dipex.org/antenatalscreening) presents people’s experiences of antenatal screening. However, antenatal screening is not the focus of either of these websites and forms a relatively small part of the whole resource. Websites have also been developed to provide information about genetic conditions (http://www.marchofdimes.com/pnhec/4439.asp; http://www.cafamily.org.uk; http://www.bbc.co.uk/health/conditions/). Their content is similar to the leaflets described above, where information is descriptive and overwhelmingly medico‐clinical in nature. These websites contain little information from a personal perspective on living with the tested‐for conditions. The developers of AnSWeR (Antenatal Screening Web Resource, a collaborative project funded by the Wellcome Trust) have aimed to fill this gap.

The AnSWeR project was coordinated by Dr Tom Shakespeare, and further details about the people involved in developing AnSWeR can be found on http://www.antenataltesting.info/credit.html. Tom Shakespeare had previously argued that there was a need to counter‐balance “the ‘medical tragedy’ information” with ‘more realistic accounts of living with a disabled child, and indeed, living as a disabled adult’. 10 For Shakespeare, ‘the best experts on life as a disabled person are disabled people themselves’ 10 and so central to the web resource are interviews with people with tested‐for conditions (Down’s syndrome, spina bifida, Turner’s syndrome, Klinefelter’s syndrome and cystic fibrosis) and their families. The developers claim that AnSWeR will ‘help couples (and single mothers) in the very difficult choices over prenatal diagnosis and termination on grounds of foetal abnormality, so they make the decisions which are best for them, and which they can live with afterwards’ (as stated in the AnSWeR proposal). The developers’ have stated that their aim was to ‘promote informed choice by giving a full picture of clinical procedures and providing a balanced account of the lives of people with genetic/developmental conditions and their families’. Our research team was commissioned to conduct an independent evaluation of AnSWeR against the developers’ aims and objectives and to gather information for the improvement and development of the resource. It is important to note at this point that the evaluation was conducted on the pilot resource and that the developers have taken action where possible to respond to the findings and recommendations, specifically those of a technical nature.

This paper focuses on the findings in relation to one key aspect of the evaluation: participants’ perceptions of whether AnSWeR provided balanced information and what they perceived balanced information to be.

Method

Design

This study aimed to evaluate AnSWeR by exploring the perceptions of groups of people with potentially different perspectives in relation to antenatal screening and disability. Three target groups were identified: health professionals, people with personal experience of the tested‐for conditions and potential users of the information resource with no known expertise in this area. Focus groups and an electronic questionnaire were used to collect the data from these groups. All health professionals were recruited after obtaining ethical and research governance approval.

Materials

Five essential criteria or themes were identified against which we evaluated the AnSWeR resource. These were accessibility, authenticity, balance, impact and usability. (http://www.library.cornell.edu/olinuris/ref/research/webcrit.html; http://www.westminstercollege.edu/library/course_research/www/web_eval/index.cfm). These themes are compatible with those found in consumer guidelines for judging the quality of a website (http://www.judgehealth.org.uk), and a number of validated tools 11 for evaluating online consumer information. 12 , 13 , 14 The facilitator’s guide for the focus groups was developed around these themes. The questions relating to ‘balance’ are presented in the Appendix.

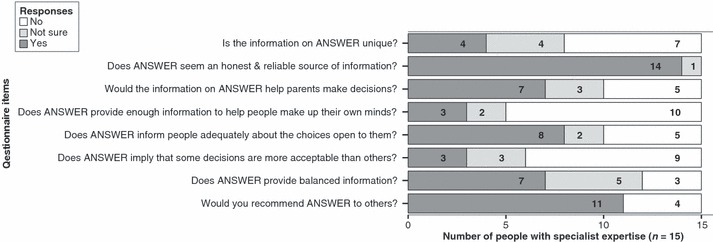

A questionnaire was developed after conducting six focus groups to allow us to select key questions from the topic guide on which we wanted to focus, for example, perceptions of balance, authenticity of the information and usability of the website. Figure 1 shows the eight items included in the electronic questionnaire. In addition, the questionnaire asked participants what they thought about the choice of personal testimonies on the website, whether there was anything they specifically liked or disliked and anything they would like to add to, or remove from the website. Questionnaires were completed by those with whom it proved difficult to arrange focus groups and with 15 health professionals with special expertise in this area. It was a pre‐requisite that participants would have access to a computer with Internet facilities. It was also assumed that people with e‐mail facilities would find it easier and quicker to complete an electronic rather than a postal questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Responses to the questionnaire from 15 people with special expertise.

Procedure

The data were collected in two phases with the emphasis on focus groups as the data collection method in phase one, although some groups completed electronic questionnaires. In phase two, professionals with known special expertise in the field of prenatal screening were targeted using the electronic questionnaires. The same questionnaire was used in phases one and two.

Phase one: potential users, people with personal experience of the conditions and health professionals

Focus groups

Eight focus groups were conducted in all. Participants for three ‘potential users’ focus groups were recruited via staff electronic distribution lists administered by the University of Leeds. Medical students were recruited via an advert e‐mailed to all fourth year medical students at the University. Third year student midwives were recruited via a midwifery lecturer at the University. These five focus groups were held at the University. Genetic counsellors/registrars were recruited via the Regional Genetics Service and the focus group was held at a hospital in Leeds. A group of mothers (including one foster mother) of young children with Down’s syndrome were recruited from a local MENCAP Nursery. This group took place at the nursery. Mothers of children with cystic fibrosis were recruited via a local parent support group identified via the Cystic Fibrosis Trust. The focus group took place at the home of one of the parents.

Electronic questionnaires

Because of the difficulties the researchers experienced in organizing focus groups with some of the target populations, it was decided to use the electronic questionnaire format developed for Phase two. Parents of newborns were approached via a local National Childbirth Trust (NCT) representative. Eleven people registering their interest were e‐mailed the electronic questionnaire. To recruit adults with cystic fibrosis, an advert was posted on a discussion group accessed via the Cystic Fibrosis Trust. One questionnaire was also completed by a daughter of one of the participants from the focus group of parents of people with cystic fibrosis. Adults with spina bifida were recruited via an advertisement in the local Association for Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus newsletter. The number and characteristics of participants are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of focus groups and participants completing the questionnaire

| Number of participants | Number of males/females | Mean age of participants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus groups | |||

| 1. Potential users (staff group) | 5 | 1/4 | 31.6 |

| 2. Potential users (staff group) | 5 | 1/4 | 37.0 |

| 3. Potential users (staff group) | 4 | 0/4 | 27.6 |

| 4. Parents of children with Down’s syndrome | 5 | 0/5 | 31.5 |

| 5. Parents of children with cystic fibrosis | 5 | 0/5 | 34.7 |

| 6. Genetic counsellors/registrars | 6 | 2/4 | 38.7 |

| 7. Medical students | 4 | 1/3 | 22.8 |

| 8. Student midwives | 8 | 0/8 | 24.1 |

| Questionnaires | |||

| Parents of newborns | 8 | 2/6 | 29.2 |

| Adults with cystic fibrosis | 3 | 1/2 | 26.0 |

| Adults with spina bifida | 1 | 0/1 | – |

| People with special expertise in phase 2 | 15 | 6/9 | – |

| Total | 69 | ||

Conducting the focus groups: Prior to attending the focus groups, all participants were provided with an information sheet in which they were asked to explore the AnSWeR website, spending as much time as they wanted on it, with a minimum of at least 1 h, 24 h prior to the focus group discussion. This approach allowed participants to navigate and pursue issues that they found interesting at their own pace. All the focus group participants explored the website as instructed except for two of the mothers of children with Down’s syndrome (one foster, and one mother who had read printed copies of some of the pages).

At each focus group a CD copy of the AnSWeR website was available for viewing using a laptop computer and projector. Where necessary, the website was navigated by one of the researchers while the other facilitated the discussion. Having the web resource available ‘live’ during the group, enabled all participants to follow the discussion and encouraged further debate. The focus groups lasted between 45 and 90 min. Each focus group was audio‐taped and transcribed verbatim.

Administering the electronic questionnaire: The questionnaire was e‐mailed to parents of newborns, people with cystic fibrosis and people with spina bifida. These participants were asked to explore the AnSWeR website, and then complete the questionnaire and return it by e‐mail.

Phase two: Professionals with special expertise

The electronic questionnaire was e‐mailed to 37 people considered to have special expertise in the area of antenatal testing: consultants and registrars in obstetrics, genetics, paediatrics and epidemiology; regional screening coordinators; midwifery team leaders and lecturers; and researchers in the field of antenatal testing.

Analysis

All transcripts were organized and coded using N‐Vivo (Nudist‐Vivo 1.2; SAGE Publications). The qualitative data were analysed using the framework approach. 15 Key themes were identified from the facilitators’ guide to form the coding framework as well as new themes that emerged from the analysis of the transcripts. Analysis involved consistent cross‐referencing between groups for similarities and differences. Analysis explored concepts, established linkages between concepts, and provided explanations for patterns or ranges of responses or observations from different sources. 16 The analysis was done by the first author (SA), who discussed the coding framework and themes with the second author (LB) to ensure consistency in interpretation of the data.

Findings

Findings on the full evaluation of AnSWeR can be found in the project report (http://www.leeds.ac.uk/hsphr/psychiatry/reports/answer_report_21_3_05.doc). This paper presents the findings on how participants viewed AnSWeR in terms of ‘balance’ using mainly the qualitative data.

Most focus groups spontaneously discussed biases and balance within AnSWeR during the early stages of discussions. Those that did not, were asked whether they believed that the purpose of AnSWeR was clearly stated by the authors, whether AnSWeR reflected any biases, and/or encouraged thinking in a certain direction, and whether AnSWeR stated the choices open to individuals.

Perceptions of balance

Respondents to the questionnaires were asked whether AnSWeR implied that some decisions (about testing and termination) were more acceptable than others: around two‐thirds of respondents (including the parents of newborns) said it did not. However, the health professional groups were more likely to say that the actual information provided within the web resource lacked balance. For example, less than half of the special expertise group said that that AnSWeR provided balanced information (7/15) in comparison to all but one of the new parents group (8/9). In the focus groups, with the exception of the health professionals, most participants were of the opinion that AnSWeR was generally balanced and that its purpose was to allow people to make ‘informed choices’. They said that this was achieved by providing people’s accounts of living with the conditions, both in childhood and adulthood:

Person with spina bifida: “This website is an impartial and informative one, which gives all aspects of the situation without swaying me one way or the other… I certainly don’t get the impression that some decisions are acceptable and others not so.”

Nevertheless, some participants in all the potential users groups said that AnSWeR presented the conditions in a more positive light:

Potential user group participant: “I felt that it was not quite giving me everything... with the Down’s cases. You kind of felt that they were the more positive end of the spectrum...”

Similarly, people with cystic fibrosis and the mothers of children with cystic fibrosis believed that the cystic fibrosis interview was ‘positive’, and that there should have been more interviews with people where the condition had a greater impact:

Person with cystic fibrosis: “I am pleased that it is mentioned that CF can vary from person to person, but the case histories should reflect this more accurately.”

Mother of a child with cystic fibrosis: “We have a friend who lost a child at 16 years old, so it doesn’t mean that every child (with cystic fibrosis) will do better.”

The health professional groups believed that AnSWeR attempted to give a realistic view of what it was like to live with various conditions, but overall they voiced strong opinions about the interviews being too positive and unrepresentative, and that AnSWeR was biased and directive in a subtle way:

Genetic counsellor: “I don’t think it gave a full range of what the difficulties can be with Down’s children... you’ve got to show the absolute positive side and you’ve got to show the reality as well, and it’s not all positive at all... you have to be more even‐handed”

All the health professional groups noted that there was one interview for Klinefelter’s syndrome and suggested that this was unrepresentative (since the evaluation, two more interviews have been added to the section on Klinefelter’s syndrome):

Genetic counsellor: “...my personal experience with young people (with Klinefelter’s) who are going through IVF or diagnosis… they have a horrific time and go through depression and suicidal attempts, and this chap was very positive... completely different…”

However, some health professionals disagreed, suggesting the interviews were representative:

Genetic counsellor: “at the risk of being contradictory... I didn’t get that feeling about the Turner’s one... I thought it was a fair description, but I mean if you’ve got a child with it you’re bound to be more positive aren’t you”

The mothers of children with Down’s syndrome generally agreed that AnSWeR was balanced. Although, one mother disagreed and stated that she was concerned that the Down’s syndrome interviews presented the condition in a negative way. She initially perceived the interviews as positive, but said that one particular interview swung the balance towards negative for all the interviews as a whole, leaving her feeling disappointed. This mother explained that she would not have opted for termination of pregnancy under any circumstances, and how she felt very positively about having a child with Down’s syndrome:

Mother of a child with Down’s syndrome: “there was nobody there that expressed how I feel, very positive. It doesn’t talk about the joy and the things that you personally learn and how you grow though that experience… maybe mine [view] is too strong on a positive side”

Nevertheless, she also acknowledged the difficulty in achieving a balance on AnSWeR, given the variation in readers’ perspectives and their different experiences:

Mother of a child with Down’s syndrome: “It can’t be easy to find the right balance. You can get two thousand people and not find the right balance, so I do appreciate that.”

Overall, most participants were of the opinion that AnSWeR provided valuable information about living with conditions, and while this information generally seemed balanced, it tilted toward the more positive end of the spectrum.

Perceptions of balance: termination of pregnancy

The way in which AnSWeR dealt with the issue of termination of pregnancy was the subject of considerable discussion within the groups. In particular, the health professionals perceived the web resource to have a ‘pro‐life’ bias. They said that termination of pregnancy seemed to be a ‘taboo subject’ within AnSWeR given that the subject was supported with comparatively few interviews that were ‘difficult to find’:

Genetic counsellor: “...it took me a while to find where it was, because it’s buried... termination shouldn’t be hidden... it should be more upfront and more as an option.”

Some participants from the other groups also said that the information presented on AnSWeR implied that termination of pregnancy was the least favoured option. This was partly because there were comparatively few interviews with women who had opted for termination of pregnancy and partly because the interviews with parents of children with Down’s syndrome and spina bifida were perceived as leaning more towards the ‘no termination route’.

Potential user group participant: “the balance was a little bit tilted towards the positive, no termination route... and the case histories were very, very positive...they did seem to be overwhelmingly, um we would never have terminated in a million years.”

In contrast to most of the health professionals, the mothers of children with Down’s syndrome said that the information AnSWeR provided on termination of pregnancy was balanced. They said that termination was presented as a choice and that it was clearly stated as being ‘up to the parents to make the right choice for them’:

Mother of a child with Down’s syndrome: “…all the way through it assures you that ‘if you decide to terminate, that is your choice’, and that is not the wrong thing to do… it was very fair.”

Participants in the potential users groups and the Down’s syndrome mothers group indicated that they would like to see more about the potential emotional impact of termination of pregnancy:

Mother of a child with Down’s syndrome: “if somebody wants to terminate …they might want to know how people felt, and why they did it, did they feel guilty that they’d done it… some people do it and wish they’d never done it…”

One participant acknowledged that giving balanced information on such an emotive and sensitive subject was difficult to achieve:

Potential users group participant: “I think it’s difficult though to give like a balanced approach... if I was to read it and then came across somebody who said “I had loads of problems after my termination and I felt guilty”… it would just take one like that to put me off it altogether, even if you put five other good ones... “

However, there was also the view that the immediate negative emotional impact of termination was perhaps overplayed:

Medical student: “...there must be people around who’ve had a termination and then had another child and moved on with their lives... and think that they made the right decision…”

There were a number of suggestions as to how the issue of pregnancy termination could be presented in a more balanced way. Participants in most of the groups said that more interviews were needed with women who had opted for termination of pregnancy, particularly where there was a dilemma for them due to the uncertain prognosis of the condition. A parent with a newborn child added that AnSWeR should also include interviews for termination of pregnancy with fathers.

Some participants suggested changing the location of the termination of pregnancy interviews. Some of the health professionals suggested the simultaneous presentation of interviews with people living with the condition and interviews with women who had opted for termination for that condition, to allow the reader to choose the option they wished to pursue. It was felt that this was more ‘balanced’:

Student midwife: “… why on that same page is there not something with an interview of somebody who decided that she couldn’t handle having a Down’s syndrome child and decided to have a termination?”

There were some participants who did not think that further information about termination of pregnancy was warranted as they believed that such attitudes are likely to be already formed. A mother of a child with Down’s syndrome added that people thinking about termination should look for further information about termination on other websites.

For the mothers of children with Down’s syndrome or cystic fibrosis, the issue of termination of pregnancy was a particularly difficult one. Although all the mothers of children with cystic fibrosis believed that AnSWeR would benefit from more interviews on termination of pregnancy, they expressed their ambivalence about this subject. For example, one mother went on to talk about pre‐implantation genetic diagnosis, and explained that while she herself could not imagine being without her son who had cystic fibrosis, others, including her other son who was a cystic fibrosis carrier, should be fully informed about the potential severity of the condition:

Mother of a child with cystic fibrosis: “…wouldn’t for a second be without my other boy (with cystic fibrosis)… but I’m saying to him (eldest son, carrier) ‘think very hard, about making a conscious decision … that you can screen an embryo …I can say that on one side, but I could never ever have screened out my other embryo. … I feel schizophrenic on that.”

As expected, there was a variety of perspectives on the way in which AnSWeR presented information about termination of pregnancy. On this highly sensitive topic, where viewpoints are often polarised, the difficulties of presenting ‘balanced’ information is particularly acute. However, there was an approximate consensus among participants that increasing the number and range of interviews with women who had terminated a pregnancy for the tested‐for conditions would give a better impression of ‘balance’.

Perceptions of balance; the role of photographic images

AnSWeR uses a number of photographic images within its pages. For some participants, these images were thought to introduce a ‘bias’; but not always for the same reasons. The web pages where information about the tested‐for conditions is initially accessed all have a photograph of a person with that condition. Some of the student midwives argued that someone who had had a positive diagnosis of one of the conditions, and who was undecided about whether or not to terminate the pregnancy, should not be immediately presented with photographs of affected individuals. They said that these photographs should be presented at the level where the user opts to read or listen to the individual testimonies:

Student midwife: “...if you’ve almost made your decision that you’re going to terminate this Down’s syndrome baby, because your family and you can’t take it, and then you’re going on this website and then you’re getting pictures, I mean they’re cute pictures... perhaps when you first go on this you just want to know about Down’s syndrome...”

Some of the mothers of children with Down’s syndrome also agreed that photographs of people with the tested‐for conditions should not be on the front page of the condition information, and that the user should have a choice to open and look at these images. However, their reasons for this preference differed from that of the student midwives. Contrary to finding the pictures of children with Down’s syndrome ‘cute’ and so discouraging of termination of pregnancy, the mothers believed that the pictures were not attractive and could discourage people from continuing with an affected pregnancy:

Mother of a child with Down’s syndrome: “…when you look at something that doesn’t look attractive, then… you automatically think ‘ooh, that person doesn’t look attractive, and can I love that person?… That’s the natural instinct, to imagine if you can love this person that doesn’t look attractive”

These mothers stated that the facial characteristics of Down’s syndrome were stigmatizing, and could create a negative reaction in people without close personal experience of affected individuals. They said that the photographs were too ‘close‐up’ and should have been taken from a greater distance to show the individual, rather than just the facial features.

Mother of a child with Down’s syndrome: “…it would frighten me… it’s the closeness of some of them. …if taken from further away, they’re not as scary, in‐your‐face, and they’re not as “Hi, I’m a Down’s person, look at me”, it’s more a picture of a person and if you look a little bit closer, then you can see the Down’s”

The mothers appeared concerned that the photographs would trigger stereotypical responses to Down’s syndrome, which would prevent potential parents from seeing the more ‘positive’ aspects of the condition. In contrast, the mothers of children with cystic fibrosis were not concerned about the photographs of people with the tested‐for conditions. They said that this was because cystic fibrosis does not have any distinguishing physical features. For this reason, the photograph of the individual with cystic fibrosis did not have the same negative impact as had the photographs of people with Down’s syndrome on the mothers of affected children. The mothers of children with cystic fibrosis agreed that if a condition resulted in people looking different, then that should be shown.

These differing views on how images of people with disabilities are thought to ‘bias’ decision‐making in relation to prenatal testing highlights the difficulty of identifying ‘neutral’ material to place on a web resource of this nature.

Discussion

This study was not carried out on a random sample of the general population, which inevitably reduces the confidence with which one can generalize from the findings. Participants were selected because of certain experiences or expertise and all were required to have a reasonably high level of computer literacy. The debate about the usefulness of web‐based resources and their dependence on the computing skills of potential users is a matter of consideration, but one which is outside the scope of this paper. In addition, the majority of participants were female. One reason for this may be that antenatal testing is seen as a ‘women’s issue’. Men may have felt that they had little to contribute to the discussion and so did not respond to our recruitment initiatives. In addition, most of those who were recruited because they had particular life experiences came from groups where the membership is predominantly women, e.g. NCT groups, Cystic Fibrosis Trust, parent support groups, and parents of children attending the local MENCAP Nursery. The views of men on prenatal testing and termination are lacking more generally and this is an important area that remains undeveloped. 8 Nevertheless, our study explored a range of stakeholders’ views and offers an interesting insight into what “balanced” information actually means.

Our evaluation of AnSWeR suggests that it has achieved its aim of providing a counterbalance to currently available websites that provide mainly clinical perspectives on disability and that the majority of participants in our study welcomed this approach. Nevertheless, the findings show that some perceived AnSWeR to lack internal balance in some important aspects. Firstly, many participants thought that AnSWeR presented comparatively little information on termination of an affected pregnancy. Secondly, some participants felt that the information provided about the tested‐for conditions seemed too ‘positive’. Thirdly, some participants felt that the photographs of people with the tested‐for conditions introduced ‘biases’. These three issues will be discussed separately.

Balance: termination of pregnancy

Many participants, particularly health professionals, believed that there were insufficient case studies on AnSWeR about termination of pregnancy. This lack was in some ways intentional because the main purpose of the resource was to provide information about the tested‐for conditions. For this reason, the page on which the termination case‐studies were presented guided people to the website of an organization should they want further information or support in relation to termination of pregnancy. However, some participants interpreted the lack of termination case‐studies as an indicator that AnSWeR was supporting the view that continuation of pregnancy (or rejecting prenatal testing) was more acceptable than termination of pregnancy. Most of the groups believed that as well as giving information about living with the condition, it was important to give information about experiences of terminating an affected foetus. Again, it was felt important that the experiences presented under the ‘termination of pregnancy’ section should be varied, that is, should include both people who felt they had made the right decision and those who regretted their decision to terminate, and that such a section should include interviews with both mothers and fathers.

Balance: information about the tested‐for conditions

A major factor in decision‐making about termination of pregnancy is the perceived severity of the condition. 17 , 18 , 19 As screening can lead on to a decision relating to termination, it is important that good quality information about tested‐for conditions is available at the screening stage. This need was recognized by the majority of participants in the present study who believed that information presented on AnSWeR about living with the tested‐for condition was essential for making ‘informed choices’. However, some participants, particularly those in the health professional groups, felt that the case‐studies presented an overly positive view of the conditions. Considering the background and aims of AnSWeR, this response was perhaps to be expected. Nevertheless, this view was not shared by all the participants, particularly the mothers of children with Down’s syndrome. All the groups agreed that more case‐studies were needed to show the range of severity of the conditions. It should be noted that AnSWeR was a pilot project with limited resources constraining the number of people whose experiences could be included to 20 and that further funding is required to increase this number.

Balance: photographs of people with the tested‐for conditions

The difficulties of presenting ‘balanced’ information on a web resource of this kind was highlighted by the differing points of views that participants held about the photographs of people with the tested‐for condition: one’s person’s overly positive image was another’s stigmatizing one. While most participants agreed that the provision of photographs was important, there were differences between the groups as to what constituted a positive or negative image. For example, the photographs of people with Down’s syndrome were perceived as mainly positive and ‘cute’ by health professionals and as negative and potentially ‘scary’ by the mothers of children with Down’s syndrome. Both the student midwife group and the mothers of children with Down’s syndrome suggested that parents should have the option to view pictures rather than them being automatically displayed alongside the written text. This was because participants believed that these ‘cute’/‘scary’ pictures could influence parents to continue/terminate an affected pregnancy.

Evidence in this area is limited, although one study has used a student sample to compare the effects of using information about Down’s syndrome in textual or pictorial form on intentions to test for and terminate an affected pregnancy. 20 This study found that a photograph of a child with Down’s syndrome, whether positive or negative (as judged by the researchers) increased concern about having an affected child compared with no photograph. A ‘negative’ photograph increased expectations of undergoing prenatal testing and termination but a ‘positive’ image did not have the opposite effect. Whether these effects would be replicated in a population of pregnant women is unknown, but the issue is particularly salient to the development of a web resource like AnSWeR, as the visual image is often a key component of Internet‐based information. Further research on the use of photographic material in medical information is needed.

Overall, the participants believed that to make informed choices about antenatal testing or termination of an affected pregnancy, potential parents should be provided with balanced information. Balanced information was thought to constitute both the positive and negative aspects of living with the tested‐for condition, and of terminating an affected pregnancy.

The findings also show that delivering balanced information is difficult, given that ‘balance’ is in the eye of the beholder. That is, different people with different experiences, values and opinions are likely to have different perceptions of what constitutes balanced information. Despite these difficulties, it is essential to develop ways of providing knowledge about tested‐for conditions in a way that can support prenatal testing and termination decisions. However, balance – when referring to something as variable and experientially related as ‘life with a disability’– is an elusive commodity. Disability is a social and political issue, and part of the difficulty of providing balanced information about tested‐for conditions is linked to this fact. Those who call for ‘balance’ in information are often coming from very different perspectives; some see a need for the balancing effect of more ‘positive’ information about disability; 10 , 21 others are concerned with the ‘accurate portrayal’ of the ‘negative’ aspects of disability. Both are of the opinion that women and their partners may be ‘misled’ into making the ‘wrong decision’ by biased information about what life is like for a person with a tested‐for condition and their family.

So how can the provision of balanced information be realised? Is ‘balance’ simply an equal proportion of ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ facts about the condition? Aside from the difficulties of agreeing what is negative and what is positive, this could be considered a rather simplistic formula for describing something as complex as quality of life. AnSWeR has attempted to move beyond this and allow people with the tested‐for conditions to talk about their lives in a way that moves the focus away from the clinical and towards the social and experiential – believing that this is more useful to those making prenatal testing and termination choices. Inevitably, by their very nature these experiences are subjective. This means that some people may perceive them to be too positive, others as realistic and yet others as negative from their point of view. Yet from the speaker’s perspective, they reflect life as they see it. It is unrealistic to expect one person’s account of their life to be ‘balanced’ from anyone else’s perspective. The balance has to come from the presentation of a range of subjective experiences and the reader (or website user) then has to identify the story or stories that resonate with their own values, experiences and situation and use these to inform their own decisions.

The method for selecting a representative range of experiences is not straightforward and requires an evidence‐based approach. This will help strengthen the validity of the resource and address criticisms of selection bias. As the developers of AnSWeR found, recruiting people willing to have their photograph and life experiences available for others to see on the Internet is not always easy (particularly so in the case of Klinefelter’s syndrome). Finding people willing to talk openly about ‘negative’‐life experiences may be more difficult than finding those whose experience is more positive. On the other hand, for some conditions it may be difficult to find ‘positive’ experiences as conditions vary greatly in their severity and impact. Developing a resource of this kind is a substantial task but an important one, and the Internet, rather than the traditional information leaflet, is possibly the ideal medium for this.

Appendix: Questions on ‘Balance’ in the Focus Group Facilitator’s Guide

‘A good web site will tell you about all of the options open to you. For something to be unbiased it must give all the points of view so that you can make up your own mind’.

-

•

Is the purpose of the website clearly stated by the authors?

-

•

Does the site achieve this purpose?

-

•

Does the website reflect a bias? (Is the site designed to sway people’s opinions?)

-

•

Did you feel that the web site authors wanted you to think in a certain way or are they giving you lots of information so that you can make up your own mind?

-

•

Does the site tell you about choices open to you?

References

- 1. Royal College of Physicians . Prenatal Diagnosis and Genetic Screening: Community and Service Implications. London: Royal College of Physicians, 1989. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nuffield Council on Bioethics . Genetic Screening: Ethical Issues. London: Nuffield Foundation, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3. General Medical Council . Seeking Patients’ Consent: The Ethical Considerations. London: GMC, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams C, Alderson P, Farsides B. What constitutes ‘balanced’ information in the practitioners’ portrayals of Down’s syndrome?. Midwifery, 2002; 18: 230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murray J, Cuckle H, Sehmi I et al. Quality of written information used in Down syndrome screening. Prenatal Diagnosis, 2001; 21: 138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bryant LD, Murray J, Green JM et al. Descriptive information about Down syndrome: a content analysis of serum screening leaflets. Prenatal Diagnosis, 2001; 21: 1057–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leoben GL, Marteau TM, Wilfond BS. Mixed messages: presentation of information in cystic fibrosis‐screening pamphlets. American Journal of Human Genetics, 1998; 63: 1181–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Green JM, Hewison J, Bekker HL et al. Psychosocial aspects of genetic screening of pregnant women and newborns: a systematic review. Health Technology Assessment, 2004; 8: iii, ix–x, 1–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Michie S, French D, Allanson A et al. Information recall in genetic counselling: a pilot study of its assessment. Patient Education and Counseling, 1997; 32: 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shakespeare T. Choices and rights: eugenics, genetics and disability equality. Disability and Society, 2001; 13: 665–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ademiluyi G, Rees CE, Sheard CE. Evaluating the reliability and validity of three tools to assess the quality of health information on the Internet. Patient Education and Counselling, 2003; 50: 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mitretek Systems . Information quality tool. http://hitiweb.mitretek.org/iq/questions.asp (accessed 4 December 2006).

- 13. Sandvik H. Health information and interaction on the Internet: a survey of female urinary incontinence. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319: 29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 1999; 53: 105–111. http://www.discern.org.uk (accessed 4 December 2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Verman D. Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction. London: Sage, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zin NK, Lincoln YS. The Landscape of Qualitative Research. London: Sage, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Verp MS, Bombard AT, Leigh Simpson J et al. Parental decision following prenatal diagnosis of fetal chromosome abnormality. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 1988; 29: 613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drugan A, Greb A, Johnson MP et al. Determinants of parental decisions to abort for chromosome abnormalities. Prenatal Diagnosis, 1990; 10: 483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Evans MI, Sobiecki MA, Krivchenia EL et al. Parental decisions to terminate/continue following abnormal cytogenetic prenatal diagnosis: ‘‘what’’ is still more important than ‘‘when’’. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 1996; 61: 353–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Figueiras M, Price H, Marteau TM. (1999). Effects of textual and pictorial information upon perceptions of Down syndrome: an analogue study. Psychology and Health. Psychology and Health, 1999; 14: 761–771. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities . Choosing the Future: genetics and reproductive decision making: The Human Genetics Commission 2004 A Response from the Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities. London: Mental Health Foundation, 2004. [Google Scholar]