Abstract

Background Guidance based on a systematic assessment of the evidence base has become a fundamental tool in the cycle of evidence‐based practice and policy internationally. The process of moving from the formal evidence base derived from research studies to the formation and agreement of recommendations is however acknowledged to be problematic, especially in public health; and the involvement of practitioners, service commissioners and service users in that process is both important and methodologically challenging.

Aim To test a structured process of developing evidence‐based recommendations in public health while involving a broad constituency of practitioners, service commissioners and service user representatives.

Methods As part of the development of national public health recommendations to promote and support breastfeeding in England, the methodological challenges of involving stakeholders were examined and addressed. There were three main stages: (i) an assessment of the formal evidence base (210 studies graded); (ii) electronic and fieldwork‐based consultation with practitioners, service commissioners and service user representatives (563 participants), and an in‐depth analytical consultation in three ‘diagonal slice’ workshops (89 participants); (iii) synthesis of the previous two stages.

Results and conclusions The process resulted in widely agreed recommendations together with suggestions for implementation. It was very positively evaluated by participants and those likely to use the recommendations. Service users had a strong voice throughout and participated actively. This mix of methods allowed a transparent, accountable process for formulating recommendations based on scientific, theoretical, practical and expert evidence, with the added potential to enhance implementation.

Keywords: breastfeeding, evidence based policy, evidence based practice, guidance, practitioner and service user involvement, public health

Background and context

As part of the work of the Public Health Collaborating Centre for Maternal and Child Nutrition, we were commissioned in 2004 to develop national (for England) public health recommendations to promote and support the initiation and duration of breastfeeding, with particular reference to what interventions would work best with low‐income groups where the breastfeeding rates are lowest. Despite breastfeeding’s critical contribution to public health 1 , 2 , 3 rates in the UK are among the lowest in Europe, 4 with families from low‐income groups having the lowest rates of both initiation and duration. 5 Recent UK policy directives 6 charged Primary Care Trusts with increasing the proportion of mothers initiating breastfeeding by two percentage points per annum with a focus on communities where women are traditionally less likely to breastfeed, and there are indications that initiation rates are starting to increase. 7 Increasing initiation and duration rates, however, remains an important public health challenge in the UK and other countries.

In the process of developing recommendations that would contribute to raising breastfeeding rates, we also aimed (i) to incorporate views from a wide constituency of practitioners, service commissioners, and service users and (ii) to examine the processes involved in moving from evidence to evidence‐based recommendation. 8 In this paper, we explore the methodological challenges encountered, and the ways in which we addressed these, with particular reference to the involvement of practitioners, service commissioners, and representatives of service users in the process.

Terminology

The term ‘practitioner’ is used in this paper to include all staff who work in relevant disciplines and sectors, and includes midwives, health visitors, medical practitioners, Sure Start workers, social services and other NHS and related sector staff in hospital and community settings.

The term ‘service users and their representatives’ is used throughout this paper. We were seeking the views of childbearing women who had experienced care related to the promotion or support of breastfeeding from any sector – hospital, community, Sure Start etc. We were however constrained by time and budget in reaching many service users directly. Instead, we worked through the voluntary sector, with organizations such as the National Childbirth Trust, La Leche League, the Breastfeeding Network, and Association of Breastfeeding Mothers. Those working in the maternity‐related voluntary sector are often relatively recent mothers themselves, as well as being lay counsellors working directly with women in pregnancy and after birth, and consumer advocates working for service change. We therefore agreed that they were very suitable participants in this process, and able to reflect the views of service users both through their own experience and their work with others.

Evidence and guidance

Guidance based on a systematic assessment of the evidence base has become a fundamental tool in the cycle of evidence‐based practice and policy internationally. 9 Several methodological debates are ongoing about the development of such guidance, including optimum ways of identifying, assessing and synthesizing relevant studies (eg 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ), the limitations of scientific evidence alone in formulating recommendations for practice, 17 and ways of using the recommendations in practice and policy to create sustained change. 9 One stage in the process, the interface between the formal evidence base derived from research studies and the formation and agreement of the recommendations – what has been termed the ‘deliberative process’ 18 – has been explored more recently. This work involves developing consensus around the interpretation of the formal evidence base, its applicability in the population groups of interest, and the feasibility of such interventions in practice. The use of consensus methods in clinical guideline development has been reviewed, 19 and there are recent examples of such consensus development in clinical guidelines (eg 20 , 21 ); though it does not always occur, or is not always reported. 18 This is a crucial stage in assessing whether the formal evidence base will really work in practice and in the wide range of relevant practice settings. 22 It is a particularly important stage in which to engage practitioners, service commissioners and service users and their representatives, who are likely to understand the issues of changing practice in real‐life settings, but whose views may not be sought when decisions are made about research or about evidence‐based recommendations. 22 , 23 In some guidance development a consultation system is in place, where stakeholders can contribute to the scope, submit written responses to draft recommendations, or attend a meeting to comment in person (eg 13 , 14 ). In other organizations, details about consultation processes are unclear (eg 24 ). Whatever the method employed, it seems important for the involvement of practitioners, service commissioners, and service users to be pro‐active, rather than limited to requesting a response once the recommendations have been drafted.

This stage is arguably most necessary in public health; the complex, long‐term, often community‐based interventions needed are difficult to evaluate with a predominantly randomized controlled trial‐based approach, and may require synthesis of a range of different methods including both quantitative and qualitative approaches. 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 Some potentially important strategies in improving public health are difficult to assess in formal research at all, such as the use of media and marketing and public policy, and information about other strategies that could be assessed using the experience of practitioners and service users is rarely sought. It can be especially difficult to assess how recommendations might work in different sub‐groups of interest, such as low‐income groups, or different minority ethnic groups.

We planned to build on the work of the English Health Development Agency in this field. 22 We aimed to develop and test a transparent and auditable approach to this crucial stage between the formal evidence base and the final recommendations; and to involve actively practitioners, service commissioners and service users and their representatives to elicit practical and expert evidence. 17 We identified three main challenges in our field: problems related to the formal evidence base; 29 , 30 the number and diversity of potential stakeholders; 31 and the short timescale and limited resources available for this work. This paper reports on the methodological issues, and examines the lessons learned for this and related fields. A separate paper will report on the results of the process.

Methods and findings

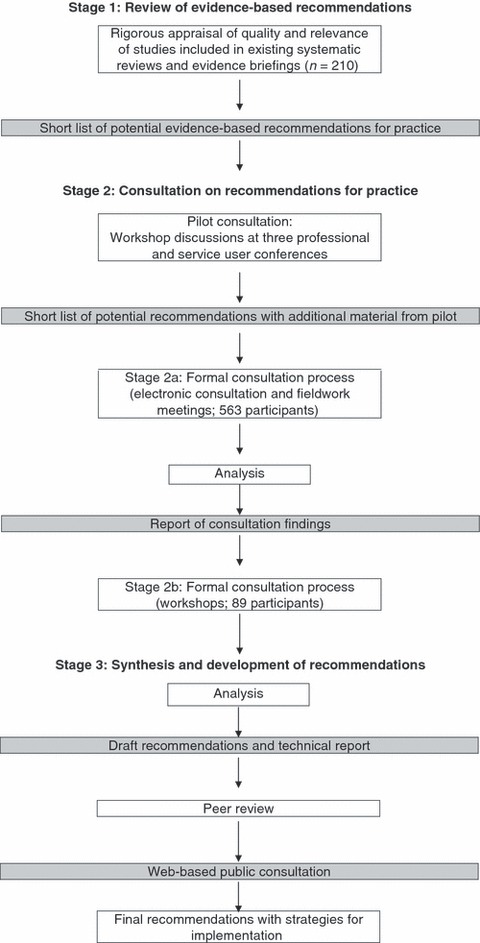

The work was planned in three main stages: (i) the assessment of the formal evidence base; (ii) a rapid consultation with practitioners, service commissioners, and service users and their representatives, including their analysis of the evidence; and (iii) the synthesis of the findings. These stages are summarized in Fig. 1. As each stage was designed to build on the previous one, the methods and findings from each stage are presented together.

Figure 1.

Details of three‐stage process.

Stage 1 – the formal evidence base

Four relatively recent reviews of interventions to increase initiation and/or duration of breastfeeding were identified. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 A slightly modified version of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) quality assessment framework was used to generate an overall quality rating for each relevant included study, 13 together with an additional set of nine criteria recommended for public health interventions. 22 A total of 210 studies and three reviews included in the four identified reviews were thus assessed for quality, salience and generalizability for use in the UK. Full details of this process are available. 36 This resulted in the generation of a list of 25 ‘plausible interventions’, based on formal evidence of good quality in relevant settings. Fifteen effective strategies were identified, including peer and professional support for breastfeeding women, and informal antenatal education. Four interventions that evidence demonstrated were harmful and should be abandoned were identified, including routine supplemental feeds and the separation of mothers and babies in immediate postnatal care. Two ineffective interventions were identified, including the use of written information when used alone. Finally, four ‘promising’ interventions were identified, where the evidence base was indicative, the theoretical base was sound, but the evidence was not as strong as for the other 21. Examples included a national policy of implementing the WHO/UNICEF Baby Friendly Initiative, and a combination of supportive care, teaching technique, rest and reassurance for women experiencing ‘insufficient milk’.

This first stage raised important issues. The formal, or scientific, evidence base had a high degree of heterogeneity, with two interventions rarely being comparable in terms of the content of the intervention, or the setting where they were implemented. It was therefore not always possible to build up a consistent picture of the effects of an intervention.

Because several topics were only examined in one or two studies, the removal of one study on the grounds of poor quality had the potential to eliminate an entire topic area for which there was no other academic evidence‐base; for example, a policy intervention such as providing workplace support for employed breastfeeding women. The high cost of implementing a high quality experimental study in a large scale, often community, setting added to the likelihood of studies being removed on quality grounds and further topic areas being lost or weakened; for example, implementation of the WHO/UNICEF Baby Friendly Initiative (http://www.babyfriendly.org.uk/). Studies of women from low‐income groups, our focus of interest, were very limited; in the largest review examined, only 12 of the total of 37 studies on public health interventions focused on disadvantaged groups. 34 In addition, interventions had been tested in settings that differed, to varying extents, from UK health and social care settings. Careful consideration of the potential for translation into UK practice would be required.

Stage 2 – consultation with practitioners, service commissioners, and service users and their representatives

A second stage to this work was designed to attempt to fill the gaps in the formal evidence base, and to understand better the contexts in which the final document would be used. A structured, rapid, two‐part consultation with practitioners, service commissioners, and service users and their representatives was developed. The consultation was intended to ensure that the final recommendations reflected a critical balance between the scientific confidence in the findings, and a realistic and practical appreciation of what would really work in practice across the primary, secondary and tertiary health‐care sectors, and in acute and community health‐care settings.

Stage 2a: initial consultation

A structured questionnaire was designed for widespread distribution to practitioners, service commissioners and service users and their representatives. Interventions identified in stage I were presented in categories of ‘effective’, ‘ineffective’, ‘harmful’ and ‘promising’. Respondents were asked to rate the impact and feasibility of each of the 25 plausible interventions on a scale of 1–5 (5 being the highest score). It was noted for each intervention whether it was likely to have an impact on rates of initiation or duration; exclusive breastfeeding or any breastfeeding; and the target group with which it had been shown to be effective/ineffective.

Respondents were also asked to contribute their views, in free text boxes, on possible problems, ways of overcoming these, and additional strategies that might work. Basic demographic information was requested, as were their views on the questionnaire itself. The questionnaire was piloted first with a small group of practitioners, and then in discussion sessions at three national conferences, which included practitioners from a range of professional groups, and service users and their representatives. Three additional policy‐related topics were suggested that had a limited formal evidence base, yet which were considered to be crucial by participants in the pilot consultations (e.g. educating schoolchildren about breastfeeding). A separate question about these three topics was included in the final questionnaire.

The questionnaire was then distributed in both electronic and paper form through extensive professional, NHS and consumer networks. This work was supported by a range of organizations who offered their networks including: all relevant Royal Colleges; professional groups such as the UK Federation of Primary Care networks; voluntary organizations such as the National Childbirth Trust, La Leche League, Breastfeeding Network, and the Association of Breastfeeding Mothers; childcare organizations; and social services. These organizations distributed the questionnaire through their own email lists, free of charge. In this way, the questionnaire was widely, rapidly and contemporaneously distributed across a range of sectors in the UK. Some 514 completed questionnaires were received in the 3 weeks allowed for responses; it is not known how many were distributed as those receiving it were asked to forward it to others who might be interested. Table 1 shows details of respondents. They represented every country and region in the UK. Around 68% of the 514 respondents were from NHS Trusts (44% acute, 24% community), with 12% from the voluntary sector, 6% from Sure Start, 4% the university sector, and 9% from other settings including child care and social services. Midwives were the largest professional group (44% of respondents), and the majority of service user representatives described themselves as breastfeeding supporters. Normally, breastfeeding supporters are women who have themselves breastfed, and who have been trained by one of the voluntary organizations to support pregnant and breastfeeding women.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in electronic consultation (n = 514)

| Characteristic of respondent | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Organization | ||

| NHS Acute Trust | 224 | 44 |

| NHS Community Trust | 125 | 24 |

| Voluntary Sector | 64 | 12 |

| Sure Start | 31 | 6 |

| University/Higher Education | 21 | 4 |

| Childcare/Social Services/Other | 45 | 9 |

| Role | ||

| Midwife | 212 | 42 |

| Health Visitor | 82 | 16 |

| Breastfeeding Supporter (Lay) | 60 | 12 |

| Lactation Consultant | 29 | 6 |

| Dietician/Nutritionist | 27 | 5 |

| General Practitioner/Paediatrician | 15 | 3 |

| Academic | 12 | 2 |

| Other (e.g. Health Promotion, Child Care, Nurses) | 75 | 14 |

| Region | ||

| London and South East | 102 | 20 |

| West Midlands | 59 | 11 |

| Yorkshire and Humberside | 52 | 10 |

| East of England | 51 | 10 |

| Wales | 50 | 10 |

| North West England | 48 | 9 |

| Scotland | 39 | 7 |

| East Midlands | 34 | 7 |

| South West England | 35 | 7 |

| North East England | 25 | 5 |

| Northern Ireland | 9 | 2 |

| Not indicated | 10 | 2 |

| Total respondents | 514 | 100 |

It was recognized that some groups were less likely and less able, due to lack of access, to participate in an electronic consultation. This stage therefore also included a series of fieldwork meetings with practitioners including Sure Start workers, midwives and health visitors working in low‐income areas (three meetings, with a total of 29 participants; a fourth was planned in London on 7th July 2005 and had to be cancelled because of terrorist attacks); a specialist, multisectoral infant feeding group (14 participants including professional, academic and service user representative participants); and interviews/questionnaires with GPs (two took part in a teleconference, four gave additional material on paper).

Analysis of the quantitative aspects of the questionnaires resulted in overall ratings of impact and feasibility for each of the 25 interventions, and for the three policy‐related strategies. A rating of ‘High’ impact or feasibility was given if the intervention was scored at 4 or 5 by 90% or more of the respondents. A rating of ‘Medium’ was given if a score of 4 or 5 was given by 70–89%, and ‘Low’ if fewer than 70% scored it 4 or 5.

Content analysis of the qualitative material was conducted by two members of the team with experience of qualitative research. It was grouped into categories representing views of use of the interventions in practice, and strategies to overcome problems.

Stage 2b: analytical consultation

This material was then taken to three workshops, each based in a multi‐ethnic, low‐income area in England; one in London, one in a town and country area in the West Midlands; and one in a large urban centre in the North of England. The workshops were designed to bring together groups which had direct experience of strategic, operational and professional roles at different levels throughout their organizations, to work alongside voluntary and independent sector workers. Planning was supported by local practitioners and service managers, who helped to distribute invitations to a cross‐section of individuals, from very junior to very senior practitioners working in sectors ranging from acute and primary care NHS Trusts, public health, Sure Starts, Children’s Centres, Non Governmental Organisations and Higher Education Institutions; and to those in the voluntary sector, aiming to involve a ‘diagonal slice’ through all the relevant sectors. Representatives of national policy makers were also invited. A total of 89 people participated in the three half‐day workshops, representing every relevant sector and ranging in seniority from midwives, health visitors, Sure Start workers and breastfeeding counsellors to senior executive level in NHS Trusts, and national policy leads.

Each workshop followed the same structure. First, details of the results of the formal evidence assessment and the quantitative and qualitative results of the first part of the consultation were presented. Participants then worked in mixed, facilitated groups of about eight, each group working in depth on about seven or eight of the list of 25 plausible and the three policy‐related interventions. Each group was given a listing of the impact and feasibility rating for each intervention as assessed by questionnaire respondents, together with a column for them to insert their own group ratings. Individuals were asked to complete their own individual rating columns if their views differed from the final group decision. They had access to details of the formal evidence base if required.

Participants were specifically asked to consider feasibility if an intervention was rated as high impact but not high feasibility, and to discuss ways in which feasibility might be improved. In this way, the groups gave ratings of High, Medium or Low to both the impact and feasibility of the total of 25 plausible and three policy‐related interventions.

Box 1 gives an example of the quantitative and qualitative material that resulted at the end of Stages 1–2b for one of the plausible ‘effective’ interventions, professional support after birth. The table shows the outcomes and target group examined in the formal evidence base, and the strength of that evidence (assessed in Stage 1), in the first four columns. The next three columns show the results of Stages 2a and b, giving the impact and feasibility ratings resulting from the questionnaire responses.

Table Box 1.

Example of practitioner and user representative ratings and views of an evidence‐based intervention: from Stages 2a to 2b

| Intervention | Outcome | Target group | Stage 1 formal evidence‐base | Stage 2a initial consultation | Stage 2b analytical consultation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workshop 1 | Workshop 2 | Workshop 3 | |||||||||

| Impact | Feasibility | Impact | Feasibility | Impact | Feasibility | Impact | Feasibility | ||||

| Professional support in early postnatal period | Duration of breastfeeding: any & exclusive | General population who want to breastfeed | RCT++ (Porteous 2000, USA) CT+ (Serafino‐Cross 1992, USA) Generalizability: Moderate | Med (347) 70% rated 4 or 5 | High (450) 90% rated 4 or 5 | Med (11) | High (10) | High (16) | Med (15) | High (14) | Med (13) |

Qualitative results from Stages 2a and b suggested that providing such support would require: (i) the implementation of good quality training for all healthcare professionals including midwives, health visitors and general practitioners, and (ii)provision of opportunities for health professionals to reflect on their own attitudes and experiences of infant feeding.

RCT, randomized controlled trial; CT, controlled trial; ++, Quality appraisal rating of study: good; +, Quality appraisal rating of study: moderate; n, number of participants

Rich qualitative information was gained by recording all discussions in the workshops. These were not transcribed verbatim, but were listened to by several members of the team and summarized with the aim of informing and explaining the quantitative ratings; direct quotes were noted to illustrate key points. This material provided context and explanation for some of the quantitative ratings, and strategies to address difficulties. Included in Box 1 are examples of qualitative material that suggested helpful strategies to enhance the recommendation.

It was notable that when participants worked as a group and were encouraged to adopt a ‘can do’ ethos, they raised the feasibility ratings of the interventions through challenging negative attitudes and traditional barriers to implementation. For example, after discussing ways of providing combined peer support and education programmes, respondents agreed to raise the feasibility from ‘low’ to ‘medium’, having provided examples of ways of doing this in practice.

The following quotes are from a discussion centred around the feasibility of providing one‐to‐one antenatal support and postnatal support for the first year, and who this should be provided by. They give a flavour of the sort of organizational change needed to make this process work effectively:

The NCT (National Childbirth Trust) and La Leche League are valuable organisations in terms of supporting breastfeeding. They should come into hospitals, I believe they have the knowledge to support staff, deal with tricky, difficult breast feeders, whatever. I have always wondered why they cannot come into a hospital. Who says that?

I worked in a Trust with a woman who had breastfed nine babies and just because she was a health care assistant she wasn’t allowed to give advice and support to women breastfeeding. It is about breaking those barriers down.

Stage 3: synthesis

Finally, the results of each workshop, both quantitative and qualitative, were synthesized by two members of the team, with input from all others. There was a striking consensus in the results across the workshops, with limited variation between them in the overall quantitative ratings for each intervention. Where differences existed, the qualitative material provided explanation, context, and strategies. Full details of this process, with a record of all decisions made, are available. 36

Box 2 shows how this material was presented for one recommendation. The final wording of the evidence‐based recommendation is presented, together with the outcomes likely to be affected; the strength of the potential impact and feasibility; a list of suggested implementation strategies; and an example of a comment made by one respondent.

Table Box 2.

Example of recommendation for effective action based on evidence‐base and consultation, together with strategies for change and direct quote from qualitative material: from Stage 3

| Additional, breastfeeding specific, practical and problem solving support from a health professional should be available in the early postnatal period for all women |

| Appropriate professional support in the early postnatal period is considered to have a HIGH impact in terms of its effectiveness on duration rates of any breastfeeding among all women. |

| The feasibility of delivering such programmes is considered to be MEDIUM subject to implementation of the following strategies for change: |

| Strategies for change to achieve effective implementation (not in order of priority) |

| 1. Professional support is essential from the first feed and throughout the first few weeks until successful feeding is established. Such support should be breastfeeding‐specific and additional to normal care. |

| 2. Continued support for up to 28 days is seen as crucial for breastfeeding support offered by midwives and to ensure continuity of support between midwives and health visitors. |

| 3. Appropriate training of all health professionals is essential to ensure consistency of message and approach at all times, across disciplines and hospital and community sectors to achieve timely continuity of care. |

| 4. Effective communication is also essential between health‐care disciplines and hospital and community sectors to achieve timely continuity of care. |

| 5. Staffing levels on wards may need to be reviewed, with innovative approaches such as employment of breastfeeding counsellors and full utilization of health‐care assistants to work alongside other health professionals. |

| 6. Ensuring appropriate professional support for breastfeeding should be considered as part of every NHS Trust’s clinical governance procedures. |

| One respondent said, this recommendation is: |

| ‘critically important. Training is essential to ensure all professionals‘sing from the same hymn sheet.’ |

The full document was then sent for peer review to seven individuals with expertise in breastfeeding both as professionals and service user representatives, and in evidence‐based practice and policy. Responses were predominantly positive. Small amendments were made.

Finally, a further, two‐stage, response‐mode public consultation was conducted, to agree the recommendations using existing mechanisms for national guidance development. 13 This elicited a range of responses, many of which testified to the strength of the consultation process already conducted. These respondents included NHS organizations that would be involved in putting these recommendations into practice, as well as professional and service user organizations. Examples of responses from this stage included:

I would like to offer my wholehearted support for the robust and comprehensive process of professional/user consultation and systematic review of relevant research evidence.

We would like to say thank you for such a thorough and comprehensive briefing. We found the document to be very coherent and informative, providing us with an excellent tool to support the work currently going on in our area.

This document is to be welcomed for its comprehensive nature including the ‘what’ and ‘why’ as well as very importantly the ‘how’. My overall view is that this much overdue but welcomed document offers grounded evidence based recommendations on many relevant and practical issues pertaining to breastfeeding

The consultation provides a comprehensive analysis of quality breastfeeding research, from which the recommendations are based on. The document is helped by providing headings such as ‘suggestions for effective implementation’.

The final document was then published. 37

Overview of the consultation process

The consultation process took 18 weeks following the formal evidence assessment. Four weeks were taken to design and pilot the questionnaire and plan the workshops, 8 weeks for distribution and return of the questionnaire, conduct of the fieldwork meetings and final workshops; and 6 weeks to complete analysis and write the final report. The final report was presented so that every statement could be verified and its origins traced.

Participants in the process were strongly supportive of the way in which it was conducted. Positive comments about the electronic consultation tool included the following;

We are very glad to be consulted in this way, and feel it would be appropriate to have some feedback and some action as a result of the consultation.

Easy to use, accessible.

I think it says all that should be done.

Please publish, shout the results from the rooftops!

Not only did participants consider it to have been an effective and efficient way of involving a range of views, but some indicated that they went on to establish networks, and to start work to prepare for the forthcoming guidance. Some also reported that when the report was published, their involvement in the process would enable them to use it in a more prepared and informed way in their own locality, thereby enhancing implementation.

Discussion

This was a rapid consultation with practitioners and service users and their representatives conducted with limited resources and timescale. It proved to be a rich source of material, providing insight into the use of research‐based recommendations in real‐world practice and policy. Respondents included individuals who were involved with and informed about the topic area, as well as those whose responsibilities involved the broader public health agenda and who were not necessarily well informed about infant feeding issues. The involvement of national user support and professional groups allowed us to draw on their extensive experience of promoting and supporting breastfeeding through a range of interventions with different target groups. This included their in‐depth knowledge of the complex factors influencing a woman’s decision to start or continue to breastfeed, particularly for those women from groups with the lowest breastfeeding rates. The interchange between the different groups resulted in increased mutual understanding of the problems that women face when breastfeeding, and that practitioners have to overcome when promoting and supporting breastfeeding, as well as the barriers to change at different levels, and the potential for different strategies to work.

Involving all of the national service user support groups in this field, as well as representatives of all the relevant professional groups, avoided the potential for rival coalitions to feel excluded from the process. Further, the open approach to distribution of the first round of consultation, which included circulation around the range of groups representing practitioners, enabled those who were not closely involved in the field to contribute, as well as those who were. Breastfeeding is a topic where there is known to be a problem with inconsistent advice and widely differing views among practitioners. 38 Despite this, our approach succeeded in reaching consensus across disciplines and between service users, practitioners, policy makers and commissioners, through the two different, open consultation mechanisms. The positive feedback from the final open public consultation demonstrated that the final recommendations were widely supported by a very wide range of groups, including those closely involved in the field and those representing broader public health interests. Such an approach could help to avoid criticism and promote acceptance by both practitioners and the public when guidance is finally published.

The combination of the widespread questionnaire‐based consultation with the diagonal‐slice analytical consultation, both using highly structured approaches, enabled the combination of different sources of evidence, including scientific, theoretical, practical and expert, 17 , 18 in a rigorous, transparent methodology. It allowed the participants to be aware at all stages of the scientific evidence base and of the input of others, and decisions and input at all stages were recorded. This resulted in an evidence‐based, accountable procedure.

The diagonal slice workshops were an especially rich source of insight, and the participants seemed to benefit from the rare opportunity to talk with others from different sectors, levels of seniority, and involvement in the field. It proved especially valuable in enabling conversation between senior practitioners and commissioners, and the voluntary sector. It offers one model for bridging the potential gap between the formal evidence base and practice/policy guidance, and has the potential for enhancing the use of evidence‐based recommendations in practice.

This approach allowed a wide range of practitioners and service users and their representatives to influence the development of the recommendations, rather than responding once they have been drafted. This is important in a topic area which covers a wide range of sectors and disciplines, and in the context of a rapidly changing service environment. It also reflects policy imperatives to involve practitioners and service users in shaping service provision and in promoting public health. 39

The range of posts, sectors and backgrounds of workshop participants was an undoubted strength of this approach in that it brought a clinical and strategic, hospital and community focus, together with multi‐agency discussion and involving the voluntary sector. There was a consistent message throughout the process that participants understood that it would be very difficult to find adequate resources to implement the final report, in part due to financial pressures on the NHS as a whole, and in part because of the low priority often accorded to breastfeeding. It appeared that the interventions were not technically challenging in themselves, but that implementing them in a complex, multi‐sectoral health economy was the real challenge. This strengthens the need for such a consultation process; input was less about changing the actual interventions recommended, more about how to implement them in real world situations. The positive dialogue about the costs involved in implementing recommendations, and ways of mitigating those costs, suggest that this process could be especially helpful in considering issues of cost‐effectiveness in future guidance and policy recommendations.

This model offers an approach to guidance development in the complex field of public health that incorporated highly‐regarded approaches to achieving changes in professional practice. The process achieved consensus, demonstrated by the comments across different phases and workshops; 19 , 21 it drew on the expertise of local communities; 20 and it incorporated expert opinion leaders across a range of sectors and disciplines. 40 A similar approach has since been used in developing evidence‐informed policy for newborn screening. 41 Such an approach could be tested in other topic areas, and could be developed into a longer, multi‐phased programme of work that would examine the impact in practice of recommendations developed in this way.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants in this consultation. NHS colleagues in North East London, West Midlands and Leeds helped to plan the workshops and Consortium partners in the Public Health Collaborating Centre for Maternal and Child Nutrition supported distribution of the questionnaires. Staff of the NICE Centre for Public Health Excellence supported the work (Mike Kelly, Tricia Younger, Caroline Mulvihill). Two anonymous reviewers provided helpful input. The work was funded by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).

References

- 1. WHO . Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martin RM, Gunnell D, Smith GD. Breastfeeding in infancy and blood pressure in later life: systematic review and meta‐analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2005; 161: 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Quigley MA, Cumberland P, Cowden JM, Rodrigues LC. How protective is breastfeeding against diarrhoeal disease in infants in 1990s England? A case control study. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 2006; 91: 245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yngve A, Sjostrum M. Breastfeeding in countries of the European Union and EFTA: current and proposed recommendations, rationale, prevalence, duration and trends. Public Health Nutrition, 2001; 4: 631–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hamlyn B, Brooker S, Oleinikova K, Wands S. Infant Feeding Survey 2000. London: Stationery Office, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Department of Health . Improvement, Expansion and Reform: The Next 3 years. Priorities and Planning Framework 2003–2006. London: Department of Health, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bolling K. Infant Feeding 2005: Early Results. London: The Information Centre, Government Statistical Service, UK Health Departments, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kelly MP, Speller V, Meyrick J. Getting Evidence into Practice in Public Health. London: Health Development Agency, 2004. http://www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=502709, accessed on 24 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, Mcfarlane F, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of Innovations in Health Service Organisations: A Systematic Literature Review. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Limited, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Atkins D, Best D, Shapiro EN (eds). Third US Preventive Services Task Force: background, methods and first recommendations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2001; 20: 3 (suppl): 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harbour R, Miller J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ, 2001; 323: 334–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). How to Use the Evidence: Assessment and Application of Scientific Evidence. Canberra: AusInfo, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). The Guidelines Manual. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Forming guideline recommendations In: A Guideline Developers’ Handbook. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2001. (Publication No 50). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weightman AL, Ellis S, Cullum A, Sander L, Turley RL. Grading Evidence and Recommendations for Public Health Interventions: Developing and Piloting a Framework. London: SURE/HDA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16. West S, King V, Carey TS et al. Systems to Rate the Strength of Scientific Evidence. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2002, 64–88. (AHRQ publication No 02‐E016) [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buetow S, Kenealy T. Evidence‐based medicine: the need for a new definition. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2000; 6: 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lomas J, Culyer T, McCutcheon C, McAuley L, Law S. Conceptualising and Combining Evidence for Health System Guidance. Final Report. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technology Assessment, 1998; 2: 1–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lanza ML, Ericsson A. Consumer contributions in developing clinical practice guidelines. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 2000; 14: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rycroft‐Malone J. Formal consensus: the development of a natiomnal clinical guideline. Quality in Health Care, 2001; 10: 238–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kelly MP, Chambers J, Huntley J, Millward L. Method 1 for the Production of Effective Action Briefings and Related Materials. HDA Evidence into Practice London: HDA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23. James Lind Alliance. Tackling Treatment Uncertainties Together. 2006. http://www.lindalliance.org/index.asp . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Guideline Clearinghouse. 2006. http://www.guideline.gov .

- 25. Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy‐making in the health field. JHSRP 2005; 10 (Suppl. 1): 6–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Petticrew M, Whitehead M, Macintyre J, Graham H, Egan M. Evidence for public health policy on inequalities: 1: the reality according to policymakers. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2004; 58: 811–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Whitehead M, Petticrew M, Graham H, Macintyre SJ, Bambra C, Egan M. Evidence for public health policy on inequalities: 2: assembling the evidence jigsaw. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2004; 58: 817–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Swinburn B, Gill T, Kumanyika S. The International Association for the Study of Obesity. Obesity Reviews, 2005; 6: 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oakley A, Strange V, Bonell C, Allen E, Stephenson J. Process evaluation in randomised controlled trials of complex interventions. BMJ, 2006; 332: 413–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Renfrew MJ, Spiby H, D’Souza L, Wallace LM, Dyson L, McCormick F. Rethinking research in breastfeeding: a critique of the evidence base identified in a systematic review of interventions to promote and support breastfeeding. Public Health Nutrition, 2007; 10: 726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smale M, Renfrew MJ, Marshall JL, Spiby H. Turning policy into practice: more difficult that it seems. The case of breastfeeding education. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 2006; 2: 103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fairbank L, O’Meara S, Renfrew MJ, Woolridge M, Sowden AJ, Lister‐Sharp D. A systematic review to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to promote the initiation of breastfeeding. Health Technology Assessment, 2000; 4(25): 1–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tedstone A, Dunce N, Aviles M, Shetty P, Daniels L. Effectiveness of interventions to promote healthy feeding in infants under one year of age: a review Health Promotion Effectiveness Reviews. London: Health Education Authority, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Renfrew MJ, Dyson L, Wallace L, D’Souza L, McCormick FM, Spiby H. The Effectiveness of Health Interventions to Promote the Duration of Breastfeeding: Systematic Review, 1st edn London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Protheroe L, Dyson L, Renfrew MJ, Bull J, Mulvihill C. The Effectiveness of Public Health Interventions to Promote the Initiation of Breast Feeding: Evidence Briefing, 1st edn. London: Health Development Agency, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Renfrew MJ, Dyson L, McFadden A, McCormick F, Herbert G, Thomas J. Effective active briefing on the initiation and duration of breastfeeding. Technical Report. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dyson L, Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, McCormick F, Herbert G, Thomas J. Promotion of Breastfeeding Initiation and Duration. Evidence into Practice Briefing. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garcia J, Redshaw M, Fitzsimmons B, Keene J. First Class Delivery; A National Survey of Women’s Views About Maternity Care. London: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit; Audit Commission, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Department of Health . Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier. London: Department of Health, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Haines A, Donald A. Making better use of research findings. BMJ, 1998; 317: 72–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stewart R, Hargreaves K, Oliver S. Evidence informed policy making for health communication. Health Education Journal, 2005; 64: 120–128. [Google Scholar]