Abstract

Background Clinicians have been slow to embrace support for patient self‐management.

Objective To explore clinicians’ beliefs about patient self‐management and specifically assess which patient competencies clinicians believe are most important for their patients.

Methods Using items adapted from the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) as a basis, a new measure that assesses clinicians’ beliefs about patient self‐management was created using Rasch analysis. The development and testing of the new measure Clinician Support for Patient Activation Measure (CS‐PAM) is described here. Primary care clinicians from the UK and the USA were recruited to participate in the survey (n = 175).

Findings The CS‐PAM reliably measures clinician attitudes about the patient role in the care process. Clinicians strongly endorse that patients should follow medical advice but are less likely to endorse that patients should be able to make independent judgements or take independent actions. Endorsed to a lesser degree was the idea that patients should be able to function as a member of the care team. Least endorsed was the notion that patients should be independent information seekers.

Discussion Clinicians’ views appear to be out of step with current policy directions and professional codes. Clinicians need support to transition to understand the need to support patients as independent actors.

Keywords: clinician support for patient self‐management, doctor‐patient communication, patient activation, Patient centered care, patient self‐management

Introduction

The changing health‐care environment requires new roles for both clinicians and patients. Demographic and morbidity trends have shifted the focus of care away from acute episodes to the management of long‐term conditions.

Chronic conditions account for 60% of deaths 1 and 70–80% of health‐care spending in developed countries. 2 These figures are predicted to substantially increase over the next two decades, representing a significant burden for patients and a mounting challenge for both clinicians and health‐care systems. 3

The Chronic Care Model (CCM) was developed to respond to this challenge and designed to catalyse the transformation of chronic illness care at the level of patients, practices, communities and health‐care systems. 4 The CCM assumes an activated patient who will take a proactive role in managing their health on a day‐to‐day basis. Lorig defined self‐management as ‘learning and practicing skills necessary to carry on an active and emotionally satisfying life in the face of a chronic condition’. 5 Patient self‐management often requires changes that can touch every aspect of an individual’s daily life, from diet and physical activity patterns, to managing symptoms and treatment regimens at home. It means many patients must learn new skills, manage their emotions, and confront and find solutions to new problems as they arise. Patients who are successful in this role of self‐manager, possess problem‐solving skills and are adept at finding and using credible information sources.

At the practice level, the CCM supports the development of productive interactions between informed and activated patients and prepared and proactive practice teams. These productive interactions are elsewhere defined as partnership working, 6 whereby patients and clinicians work as equals, bringing complementary skills and knowledge to their working relationship. Core competencies for partnership working have been described for clinicians (http://www.newhealthpartnerships.org) and one such competency is that clinicians should provide self‐management support for patients with chronic conditions. That is, under the CCM, the clinician’s role is to understand the challenges that chronic illness patients face and provide appropriate support to them. It is the clinician beliefs about the importance of patient self‐management behaviours that are the focus of this paper.

The transformation of professional roles from health‐care provider to health‐care collaborator is supported by quality and policy initiatives in the USA 7 and the UK 8 and is embedded in professional codes and standards in both countries. 9 , 10 An additional reason to support the transformation of the traditional professional role is provided by survey data that show that patients with chronic conditions want to be more active partners in care and to be supported by their clinicians in acquiring self‐management skills and behaviours 11

Despite all this, we know from data from Australia, Canada, Germany, New Zealand, the UK and the USA that less than two‐thirds of patients say that their clinician involves them in treatment choices or negotiates a plan for managing chronic conditions at home. 12 UK data suggest that the figures are lower than this, with 43% of patients being involved in making decisions about treatments and 45% being involved in making a plan to manage their condition at home. 13

For many clinicians, partnership working clearly represents a significant shift in their perceived role, and one that they currently do not embrace. There is agreement that clinicians will need to develop new knowledge, skills and behaviours to manage the increasing demands of chronic disease 6 , 14 and a number of training organizations and professional bodies have developed core competencies to support patient self‐management. 14 , 15 For practicing clinicians, many of whom were educated in a paradigm designed to manage acute illness, these competencies represent a significant shift from disease‐ to person‐centred health care.

The literature on clinicians’ attitudes and beliefs regarding patient self‐management is sparse. One study utilizing qualitative in‐depth interviews indicates that while patient self‐management is valued, it tends to get a lower priority in the time‐squeezed medical encounter. 16 A separate study, also utilizing in‐depth interviews, indicates that clinicians rely heavily on didactic methods rather than trying to engage the patient in problem solving or by using more interactive approaches. 17

Because of this paucity of research, our study is designed to explore clinician beliefs about the importance of patient self‐management competencies and behaviours. We do this by using an adaptation of a measure designed to assess patient activation.

Background on patient activation

The survey instrument used in this study is an adaptation of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM). 18 , 19 The PAM was developed to assess an individual’s knowledge, skill and confidence for self‐management. It is an interval level, unidimensional, guttman‐like scale.* The measure was developed using Rasch modelling and has been shown to be both valid and reliable. 18 , 19 An early step in the development of the PAM was to determine the competency areas necessary to successfully manage with a chronic condition. This was done using an expert consensus process, patient focus groups and by reviewing the existing literature. As the PAM focuses on the various patient competencies needed to successfully manage life with chronic illness, the content of the items presents an opportunity to explore the degree to which clinicians support, or at least view as important, these same key patient competencies.

Our specific research questions are:

-

1

How well does a measure adapted from the PAM assess clinician beliefs and attitudes about patient self‐management?

-

2

Which elements of the patient’s role are most strongly endorsed by clinicians?

-

3

Which elements of the patient’s role are least strongly endorsed by clinicians?

-

4

Are there differences by demography or country in clinician beliefs about patient self‐management?

Methods

Instrument development and data analysis

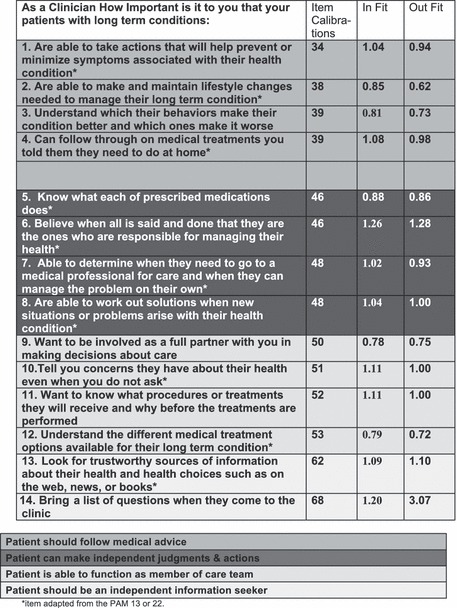

Items from the PAM were used as the basis for the items in the Clinician Support for Patient Activation Measure (CS‐PAM). In the PAM, the items ask about the individual’s ability to engage in the different behaviours. In the CS‐PAM the items are prefaced with the question: ‘As a clinician, how important is it to you that your patients with long term condition are able to…’. Fourteen items were included in all. Eleven of the 14 items are translated directly from either the original PAM (22 items) or from the short‐form PAM (13 items). 18 , 19 Three items are adapted items assessing behaviours that are known to correlate with the PAM and also are relevant to the medical encounter (items 9, 11 and 14 in Fig. 1). The intent of the CS‐PAM is to determine the degree to which the patient behaviour or skill is viewed as important by the clinician.

Figure 1.

Items and item calibrations for CS‐PAM.

Rasch analysis is used to create the CS‐PAM. The Rasch measurement can be used to create interval‐level, unidimensional, probabilistic Guttman‐like scales from ordinal data. The measurement model calibrates the ‘difficulty’ of the items in terms of response probabilities. It creates a measure with a theoretical scoring of 0–100. The calibration of an item on the measurement scale indicates how difficult it is for respondents to endorse or agree to that item. The item calibrations are established separately from the individual respondent scores.

Research question 1, which focuses on the psychometrics of the measure, is answered using Rasch Analysis and Cronbach’s α to determine the reliabilities and the in‐fit and out‐fit scores of the new measure. Research questions 2 and 3, which focus on identifying the items that are most and least strongly endorsed, are answered using Rasch analysis to determine the calibrations, or difficulty level of each of the individual items. Research question 4, which focuses on demographic differences, is answered using chi‐squared statistics.

Study population

A UK and a US sample of clinicians are included in the study. All were recruited through their clinical setting.

The US clinicians were recruited from Peace Health, a health system serving the Pacific Northwest region of the USA. All primary care clinicians in the six north‐west regions of the Peach Health system were recruited to participate in the survey. Email letters from regional medical directors were sent to all of the 95 primary care physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants. A follow‐up reminder email was sent out 1–2 weeks after the initial invitation to respond was sent. The survey was available on the Peace Health intranet, and all respondents took the survey on‐line. Seventy‐seven primary care physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants responded, yielding an 81% response rate. Data collection took place in April 2008.

The UK sample was drawn from the Somerset Primary Care Trust in the south‐west of England. The Trust serves a population of 350 000. Two hundred and eighty primary care practitioners (all those associated with the Trust) were invited by email to complete an on‐line survey. A follow‐up email was sent 3 weeks later. Ninety‐eight primary care physicians responded, yielding a 35% response rate. Data collection occurred in April 2008.

Findings

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study sample, 55% of the respondents were from the USA and 90% were physicians, and 56% were male (although only the US sample included respondent gender). Table 2 shows the practice characteristics, relevant to patient self‐management of the respondents. Here the results are shown separately for the USA and the UK. Clinicians from both the USA and the UK perceived that their office staff functioned as a cohesive team. Ninety‐one per cent of US clinicians agree or strongly agree with this statement, while 98% of UK clinicians agree or strongly agree. More variation is seen on the last two items. Ninety‐one per cent of UK clinicians indicate that they agree or strongly agree with the statement that they have a nurse or other professional who provides education and coaching to patients, while only 57% of US clinicians agree or strongly agree with this statement (P < 0.01). Similarly, significantly more UK clinicians agree or strongly agree that they collaboratively set behavioural goals with patients (84%) than do US clinicians (71%). Thus, it appears that these UK clinicians have practices that are more geared toward supporting patient self‐management.

Table 1.

Description of the study sample (N = 175)

| Professional category | |

| Physicians | 90 |

| Nurse Practitioners | 7 |

| Physician’s Assistant | 3 |

| Age (years) | |

| <40 years or less | 20 |

| 41–50 | 38 |

| 51+ | 42 |

| Gender* (male) | 56 |

| Years in practice | |

| 0–5 | 10 |

| 6–10 | 18 |

| 11–15 | 34 |

| 16–20 | 24 |

| 20+ | 14 |

All values are given as percentage.

*Only the US sample (N = 98) included data on respondent gender.

Table 2.

Practice characteristic relevant to patient self‐management

| US (N = 98) | UK (N = 77) | All (N = 175) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Your own immediate staff members function as a cohesive team in providing patient care (non‐significant) | |||

| Strongly disagree | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Disagree | 8 | 1 | 5 |

| Agree | 38 | 47 | 42 |

| Strongly agree | 55 | 51 | 53 |

| You have a nurse or other health professional in your practice who provides education and/or coaching to your patients with long term conditions (P < 0.01) | |||

| Strongly disagree | 15 | 2 | 8 |

| Disagree | 28 | 7 | 16 |

| Agree | 39 | 51 | 46 |

| Strongly agree | 18 | 40 | 31 |

| Collaboratively working with patients to set behavioural goals and develop action plans is a routine part of the care you provide (<0.05) | |||

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Disagree | 26 | 16 | 20 |

| Agree | 51 | 55 | 53 |

| Strongly agree | 21 | 29 | 25 |

All values are given as percentage.

P‐values refer to statistical significance between the responses for US and UK clinicians (chi‐squared test).

When we examined the relationship between the practice characteristics and the individual scores on the CS‐PAM, only one item was significantly linked with higher scores (data not shown). Having a staff person who educates and coaches patients is significantly associated with higher CS‐PAM scores; however, this is only true for US clinicians. Among UK clinicians this practice characteristic was unrelated to scores. This may be because there was little variation on this characteristic among UK respondents, with 91% indicating that their practice had this type of support staff.

How well does a measure adapted from the PAM assess clinician beliefs and attitudes about patient self‐management?

The Rasch analysis yielded a measure that included all 14 items with overall good psychometric properties. We assess the reliabilities using Classical Test Theory (CTT), as well as the Rasch analysis. The Cronbach’s α, from CTT, indicates whether there is consistency in the set of variables for measuring a single construct. The 14‐item measure yielded a Cronbach’s α of 0.86, well within acceptable limits. Rasch provides a different measure of reliability, an overall person reliability. Person reliability is used to indicate the degree to which a person’s response pattern conforms to the model (or difficulty structure of the measure). The person reliability is 0.80, which is also within acceptable limits and comparers well with the PAM 13, which has an overall person reliability of 0.81. The ‘in‐fit’ and ‘out‐fit’ statistics for each item were also calculated and are shown in Fig. 1. In‐fit statistics are sensitive to unexpected patterns of observations by persons on items that are roughly targeted on them, while out‐fit statistics are more sensitive to unexpected observations by persons on items that are relatively very easy or very hard for them. All of the in‐ and out‐fit scores are within acceptable limits (0.5–1.5), except for one out‐fit score.20 However, out‐fit problems are less of a threat to measurement than in‐fit ones. †

Rasch ‡ creates a theoretical 0–100 scale. The 14 items calibrated between 34 and 68. This indicates that it is measuring beliefs in the middle range, and does not tap into very high or very low values of clinician support for patient activation. The item calibrations indicate, in a probabilistic sense, how difficult it is for a respondent to endorse or agree to that item.

What elements of the patient’s role are most strongly endorsed by clinicians? Which elements are least endorsed by clinicians?

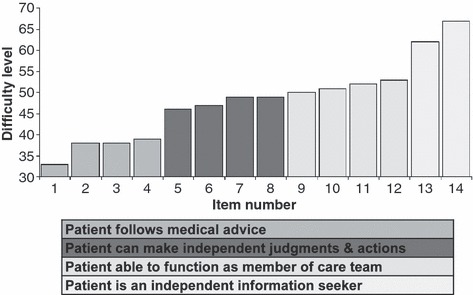

1, 2 show the item calibrations for the 14 items included in the CS‐PAM. The items at the low end are the ones it is easiest for clinicians to endorse (or indicate it is important). The items at the high end are the ones least likely to be endorsed by clinicians. Respondents who endorsed item number five probably also endorsed items one to four.

Figure 2.

Difficulty structure of 14‐item Clinician Support for Patient Activation Measure.

By ordering the items by their calibration values, a strong pattern emerges. The items with similar calibration scores also have a similar content. For example, the item calibrations for the first four items in the above table are similar, with values falling between 34 and 39. These items largely focus on the importance of patients following medical advice. These items are the most strongly endorsed by both UK and US clinicians.

The next set of four items also have similar calibrations to each other, they range from 46 to 48 for the study sample. These items tend to focus on the importance of patients making independent judgements and taking independent actions. These items are less strongly endorsed by the clinicians than the first set.

The next four items have similar calibrations to each other, ranging from 50 to 53. These items also have a similarity in their content, focusing on the importance of the patient being able to function as a member of the care team. These items were among the less likely to be endorsed by clinicians.

The last two items have the highest calibrations, ranging from 62 to 68. These items focus on the importance of the patient independently seeking information. These items are the least likely to be endorsed by clinicians.

Are there differences by demography or country in clinician beliefs about patient self‐management?

There were no differences in CS‐PAM scores between UK and US clinicians, both had average scores of 69. However, the variation in scores for both samples ranged from 10 to 100 (SD for US sample 12.1; SD for UK sample 12.8). Some differences by age were observed, with younger clinicians scoring higher: those under the age of 50 years had an average CS‐PAM score of 70, while those over the age of 50 years had an average CS‐PAM score of 67. A similar finding was observed for years in practice: those with less than 20 years in practice had an average CS‐PAM score of 70, while those with more than 20 years of practice experience had an average CS‐PAM score of 65. However, these differences did not reach statistical significance. No differences in CS‐PAM scores by professional training were observed.

Discussion

The findings from this study indicate that the CS‐PAM has acceptable reliability and can assess and differentiate clinicians on their beliefs and attitudes about the importance of patient self‐management competencies and behaviours. The CS‐PAM score indicates an individual clinician’s overall level of endorsement or belief about the importance of patient self‐management, as well as, beliefs about the importance of specific patient competency categories.

Clinicians appear to value most highly patient behaviours that focus on following medical advice; yet, these behaviours are far from sufficient for patients to successfully manage life with chronic conditions. Effective self‐management means acquiring the skills and knowledge to be able to manage symptoms and to confidently manage new situations as they arise; it requires that patients take independent actions and make independent judgements, such as being able to determine when they need care and when they can manage the problem on their own.

In this study, although we measured clinician’s beliefs about patient roles, we did not measure clinician behaviour with regard to actually supporting patient self‐management. Other factors limit the generalizability of the findings, including the small sample sizes, the response rates and the small number of non‐physicians in the study. However, the measure does appear to reliably measure clinician beliefs and further research with larger more diverse samples, which seeks to link CS‐PAM scores with clinicians’ behaviours is warranted.

The clinician views, reported here, on the relative importance of patient competencies are out of step with emerging professional codes and standards for performance. They are also out of step with larger health policy directions that seek to engage consumers and patients to be informed and activated managers of their own care. Ultimately, clinicians will have to come to understand that a part of their job is supporting the patient as an independent actor. As this direction represents a significant change from how many clinicians currently understand their role, finding ways to support them, in making this transition is imperative.

Funding

Funds for this study were provided by the Commonwealth Fund and the Nuffield Trust.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Loren Barlow of Peace Health, the Peace Health system and Martin Tusler for data analysis. We also gratefully acknowledge the support of Professor Chris Ham, Robin Osborn, Dr Tom Blakeman and Dr Patrick Hill each of whom commented on earlier drafts of this paper.

Footnotes

In a Guttman scale, items are arranged in an order so that an individual who agrees with a particular item most likely agrees with items of lower rank order. An example would be a test of math achievement where questions might be ordered based on their difficulty.

All of the items, save one, fall well within the 0.5–1.5 acceptable range for in‐fit and out‐fit scores. The item that asks about ‘bringing a list of questions to a doctor office visit’, showed an outfit score that was quite high for both the UK and the US samples (3.0). A high outfit score indicates that this item is far away from where the clinicians are. As the in‐fit score on this item is within acceptable range, the outfit indicates that this is the most difficult item and the responses on this one item were far harder for the clinicians to agree with than the other items.

Rasch models are typically used for assessments that seek to measure things such as abilities or attitudes. In this case Rasch models are used to measure the ability to self‐manage one’s own health. The mathematical theory underlying Rasch models is in some respects the same as item response theory. However, Rasch models have a specific measurement property that provides a criterion for successful measurement. This formal property distinguishes Rasch models from other models used to model people’s responses to items or questions. Application of the models provides diagnostic information regarding how well the criterion is met. Application of the models also provides information about how well items or questions on assessments work to measure the ability or trait. 20

References

- 1. World Health Organization . 10 Facts About Chronic Disease. Available at: http://www.who.int, accessed on 08 April, 2009.

- 2. UK Department of Health . Raising the Profile of Long Term Conditions Care. A Compendium of Information. London: UK Department of Health, January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization . Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions. Building Blocks for Action. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Affairs (Millwood), 2001; 20: 64–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lorig K. Self‐management of chronic illness: a model for the future. Generations, 1993; XVII: 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hasman A, Coulter A, Askham J. Education for Partnership. Developments in Medical Education. Oxford: Picker Institute Europe, May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Academy of Pediatrics . Joint Principles of a Patient‐Centered Medical Home. Available at: http://www.medicalhomeinfo.org.

- 8. UK Department of Health . Supporting People with Long Term Conditions. London: UK Department of Health, January 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Medical Professionalism Project . Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician’s charter. Lancet, 2002; 359: 520–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. UK General Medical Council . Good Medical Practice. London: UK General Medical Council, November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11. UK General Medical Council . Self Care. A National View in 2007. London: UK Department of Health, June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, Doty M, Zapert K, Peugh J. Taking the pulse of health care systems: experiences of patients with health problems in six countries. Health Affairs, 2005; WS: 509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coulter A. Engaging Patients in their Healthcare: How is the UK Doing Relative to Other Countries. Oxford: Picker Institute Europe, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Doctors in Society . Medical Professionalism in a Changing World. Report of a Working Party of the Royal College of Physicians of London. London: Royal College of Physicians, December 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. UK Department of Health . Care competencies to support self care. London: UK Skills for Health and Skills for Care; May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blakeman T, Macdonald W, Bower P, Gately C, Chew‐Graham C. A qualitative study of GPs’ attitudes to self‐management of chronic disease. British Journal of General Practice, 2006; 56: 407–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Macdonald W, Rogers A, Blakeman T, Bower P. Practice nurses and the facilitation of self‐management in primary care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2007; 62: 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Services Research, 2004; 39 (4 Pt 1): 1005–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Services Research, 2005; 40 (6 Pt 1): 1918–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith RM. Polytomous Mean‐Square Fit Statistics. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 1996; 10: 516–517. [Google Scholar]