Abstract

Objective This paper examines staff views about legitimacy of different roles for community representatives sitting on health service committees as part of a formal Community Participation Program (CPP) in an Area Health Service (AHS) in Australia.

Design A cross‐sectional survey using a self‐completed questionnaire by staff on committees with community representation in the AHS in 2008.

Setting The study site has a population of approximately 1.4 million and covers 6000 km2. The population is ethnically and socio‐economically diverse.

Results There are generally positive staff attitudes at this AHS for community participation as part of the CPP with positive impacts identified, including on service delivery and the conduct of health service meetings. Most saw community representatives having legitimate roles in representing the community, improving communication between the health service and the community and providing constructive feedback. However, staff expectations about the community’s role on committees do not match the reality they say they observe and less than half the staff thought the community and health service agree on the role of community representatives.

Conclusions As well as reviewing and enhancing training and support for representatives and staff as part of the CPP, there is a need to question staff expectations about community members who sit on health service committees and whether these expectations are shared by other key stakeholders, most notably the community representatives themselves. These expectations have implications for the CPP and for similar programs designed to engage community members on committees and working groups with health professionals.

Keywords: committees, community participation, community representatives, health services, planning

Introduction

There are ideological, moral and practical arguments why consumers should participate in health care decision‐making including people’s basic right to contribute to their care and the system they fund, accountability pressures in health care, increased effectiveness and appropriateness of health services based on consumer input, and the empowerment of those users who participate. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Health care policies in Australia and the UK have promoted the involvement of patients and community members in the planning and delivery of health services for decades, citing these types of arguments as reasons. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12

In the UK, mechanisms to involve the community, patients and users in the National Health Service through community councils, patient and public involvement forums and most recently Local Involvement Networks have been plagued by the recurring issues of questionable representation, unclear roles and a poor evidence base for effectiveness. 3 , 6 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 Similar debates abound in the Australian context 17 , 18 , 19 and in the wider international literature. 2 , 20 , 21

In a recent commentary, Entwistle raised the importance of not only examining the views that consumers, users or community participants hold of themselves, but the perspectives that those they interact with have about them, 4 views which are critical to them being heard in the first instance even before the question of influence comes into play. Positive staff attitudes to community participation, including valuing the knowledge of community members, have been identified as important in effective partnerships with communities in decision‐making. 11 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 The centrality of organizational culture, professional attitudes and resistance, leadership and the role of key staff as champions were identified in a recent systematic review of patient and public involvement in the UK as important to effective public and patient involvement. 13

There have been a few studies that have examined staff and professional attitudes to community, consumer or lay participation in specific organizational contexts and processes. 22 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 Surveys conducted in Australian drug treatment and mental health services have found positive staff attitudes to consumer participation. 31 , 32 Another Australian survey found staff attitudes become more positive over time and as a direct result of interaction with community members in health care decision‐making forums. 30 However, no studies that we have been able to uncover have had a large enough sample to permit satisfactory levels of generalizability about staff attitudes to an ongoing formal community participation program across a large health service.

This paper addresses this gap and includes the views of 142 staff in nine hospitals in an Area Health Service (AHS) about community participation, in particular the role of community representatives on committees, as part of a Community Participation Program (the CPP) which has been in operation in the AHS for nearly 10 years. Measuring staff attitudes to community participation is important to determine program acceptability at this AHS which can have a significant influence on the impact of community participation on health service actions. 3 , 11 , 13 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 26 The data have wider implications beyond the study site for other community participation strategies where community representatives are appointed to committees or working groups with health professionals. Clarity and agreement between different stakeholder groups about the roles community representatives can and should take on have been identified as a major obstacle to effective community participation. 5 , 33 , 34 , 35

The Australian context

Australia has a long but patchy history of consumer or community participation in health care with many different models proposed, implemented and re‐configured. Insufficient attention has been paid to the underlying issues of representation, expertise and the roles of those who participate in community participation processes. 36 , 37 Australia is a federated system of six state and two territory health jurisdictions. The national government funds health professional services through Medicare, the national insurance system, and block funds the state and territory governments to provide hospital, public health and community services. 23 As a consequence of these funding arrangements, consumer and community participation has been largely decentralized. The states and territories have implemented a diversity of policy responses, many with questionable effectiveness. 38 , 39 Beyond state and territory directives, the main impetus for consumer and community participation in Australian health services is a non‐mandatory community participation accreditation standard. 38

Methods

The study site

New South Wales (NSW), the state with the largest population in Australia, has eight Area Health Services (analogous to UK Trusts). The study site is the most populous AHS in NSW, with approximately 20% of the NSW population residing within its borders. 40 It covers a land area of 6380 square kilometres and has a population of approximately 1.42 million. It is the most ethnically diverse AHS in Australia with 39% of the population speaking a language other than English at home. The area is further characterized by a large number of recent migrants, and significantly higher levels of unemployment and social disadvantage than in many other areas in NSW. 40

The Community Participation Program Structure

The study site has a long history of consumer and community participation, which was formalized in 2001 with the employment of an Area Community Participation Manager who undertook a baseline audit of activities. The subsequent structure agreed between community advocates and the AHS was for each hospital to have a Community Representatives Network – CRN (see Box 1) of all interested community members which then elects representatives to an overarching Area Consumer Community Council (see Box 2). Each hospital facility over the next few years employed a Community Participation Coordinator to develop a CRN at their local service. By 2004 the practice was well embedded in about half of the AHS and by the time of the 2008 survey reported here all AHS hospitals had a network in operation and had community participation on at least some of the hospital governance committees (such as patient flow, infection control, discharge planning and clinical quality and safety), and on working groups and specific projects, such as clinical re‐design.

Table Box 1.

Community representative networks

| The role of each local network is to bring together a broad group of community residents to: | |

| 1. Advocate for consumer, carer and community participation | |

| 2. Enhance area health service understanding of the community issues and concerns | |

| 3. Make recommendations to the Consumer Community Council on common issues and concerns | |

| 4. Share information | |

| 5. Support community representatives on health committees | |

Table Box 2.

The Consumer/Community Council (CCC)

| The Consumer/Community Council is comprised of elected representatives of each local network and identified population groups including people who are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders, people with disabilities, mental health consumers and carers and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. A key role of the Council is to monitor Area Health Service commitments to community participation as well as present the views of the networks as a representative body on Area plans and policies |

A Community Participation Framework, 41 developed with community input, is the key document that identifies a range of commitments by the AHS to community participation and community participation is now a key performance indicator for health service managers. First written in 2004 and updated every 2–3 years the Framework provides guidelines in undertaking community participation processes and projects and is widely disseminated and promoted to health services and the community. The Framework states that the aims of community participation in the Area are to ensure:

-

1

Consumers, carers and the community are involved in planning, delivery and evaluation of services.

-

2

Local communities are well informed.

-

3

There is transparency and accountability in decision‐making and evaluation.

Training and support

All new community representatives undergo an orientation session, which is mandatory and introduces them to their roles and responsibilities including where they fit into the overall health service structure (see Box 3). The framework stresses that community representatives work in ‘partnership’ with the health service to improve health care delivery, that their role on committees can promote greater public confidence in health services and ensure a broader non‐professional view‐point.

Table Box 3.

Key roles and responsibilities of a community representative

| Roles |

| Protect the interests of carers, consumers and the community |

| Present how carers, consumers and the community may feel and think about certain issues |

| Contribute the consumer or carer experience |

| Ensure committees recognize community concerns |

| Report activities of committees to consumers and the community |

| Responsibilities |

| Attend regular Network meetings |

| Bring a carer, consumer or community perspective |

| Represent collective views, concerns and issues rather than their own person opinions, individual views or interests |

| Act as two way communication link between the network, health service and broader community |

| Observe confidentiality requirements of committees, sign a code of conduct and do not speak on behalf of the area health service |

Each community representative is matched with a health service staff member when joining a committee or working group. 41 This staff member is their ‘buddy’ and is charged with providing assistance and support for the representatives to be able to actively and confidently participate on the committee. Training is provided to staff and committees seeking community representatives by the Area Community Participation Unit and local Coordinators. Staff responsibilities detailed in the framework are to consider why they want a community representative, what they hope to achieve and the level of involvement required as well as to organize a ‘buddy’ for the community representative. Staff are also to ensure the committee understand the role of the community representative and have mechanisms in place to communicate committee activities. Each committee is mandated to have a minimum of two community members. The Area or local Community Participation Coordinator then assists in matching the needs of the committee and its focus to the selection of an appropriate community network member.

Who are community representatives?

Community representatives are recruited through local newspapers and ‘word of mouth’. Community representatives usually have a connection with a particular hospital in their area as a patient, carer or volunteer. The Framework outlines specific selection criteria and attributes for community members who wish to join networks (see Box 4) many of whom are then appointed to local and AHS committees.

Table Box 4.

Key selection criteria and attributes for community network members

| Lives within the Area Health Service (AHS) |

| Is not an employee of the AHS |

| Willing to commit time to attend scheduled meetings |

| Able to relate own experience of health care to broader consumer issues |

| Able to represent and respect the views of other people who use the health system |

| Have some knowledge of the health system and experience on a committee or representing other people |

Community representatives are chosen to reflect as much as possible the diversity of the local community. 41 Many are active users of health services, carers or people with an experience or understanding of mental illness or a disability. People from a culturally and linguistically diverse background have been more difficult to engage although their numbers are increasing. Younger people and indigenous community members are also more difficult to recruit as community representatives.

Study design and survey instrument

A cross‐sectional survey was undertaken using a self‐completed questionnaire for staff on health service committees with community representation in the AHS. Staff were provided with a hard copy of the survey instrument by the AHS Manager for Community Participation or the Community Participation Coordinator at the local health service in early 2008 and asked to complete and return to the Area Community Participation Unit or anonymously to the local Coordinator. Staff were reminded to complete the survey by email and verbally at meetings.

The questionnaire was developed from a validated survey instrument. 42 The survey was expanded to include new questions about the specific types of roles community representatives could have on committees which were informed by discussions with staff, community representatives and Community Participation Coordinators. The survey instrument was piloted with a sample of nine senior management and clinical staff at two local facilities to ensure clarity of the questions and scope of response options. Minor grammatical changes were made as a result.

The first 18 items of the questionnaire collected opinions about the value and influence of community representatives on committees, the role of community representatives on committees and staff and organizational support for community representatives and were drawn from the previously validated instrument. These questions recorded agreement with a range of statements on a five‐point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Two questions asked respondents to agree with specific roles they thought community representatives should have on committees and which roles they actually assumed in practice. They could tick more than one option. The questionnaire also asked an open ended question about whether respondents could provide an example of the impact of community participation at the AHS. To characterize the sample staff were also asked to answer yes/no to whether they had been on a committee with community representation, been a chair of a committee with community representation or been a buddy or support person for a community representative. Lastly they were asked to categorize position as Administration, Clinical, Management or Other. The survey instrument is available at http://www.sswahs.nsw.gov.au/SSWAHS/Community/pdf/CP_Survery_Staff_2010.pdf.

Data analysis

Data analysis was undertaken using the Statistical Package for Social Scientists –spss. 43 Descriptive statistics were examined for all questions and chi‐square tests of significance were undertaken to compare different groups and responses. Open‐ended question responses were coded into overarching themes or areas by the first author.

Results

The overall response rate to the survey for staff was 56.1% (142 out of 253 questionnaires) giving sufficient power for comparisons by different staff type, but not by local health facility. The staff sample comprised 60.5% management, 16.1% administration and 24% clinical positions. Ninety‐four per cent of staff had been on a committee with community representation, 26% had been the chair of a committee with community representation and 19% had been a buddy or support person for a community representative in the last 2 years. There were no significant differences by staff type or experience as a buddy or chairperson for any of the data presented in this paper.

Attitudes about the value and influence of community representatives

The attitudes of staff about the value and influence of community representatives on committees were generally very positive as has been found previously at one health facility in this AHS. 30 Survey respondents were asked to provide an example of how community participation had had an impact. These responses were categorized into themes. Over 60% of staff representatives responded to this question. Some 10% of these staff made a point of commenting that they had seen no impact or were not aware of any impact. The remaining respondents to this question gave positive examples of impact. The most common type of impact identified by staff were in strategic planning, priority setting, service re‐design or service delivery, followed by the impact on the conduct of meetings and improved signage and patient information. Improved communication between the health service and the community and improved access and physical aspects of the health service were mentioned by a smaller number of staff (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of staff comments about impact

| Strategic planning, priority setting, service re‐design or service delivery |

| Has made the Carer’s Action Plan more responsive and raised important issues |

| Provided community perspective for development of discharge risk assessment tool |

| Provided impetus to establish a program to support families with a child in hospital |

| Insight into factors associated with discharge planning and management of patients in the community following discharge |

| Conduct and operation of the meetings |

| Cut ‘jargon’ of meeting making it more people friendly |

| Committees seem to stay more on track when community representative is present and the work of committee is more transparent |

| Keep meeting focused on the ‘patient’ not the institution which is great |

| Improved transparency in Health Service |

| Improved signage and patient information |

| Improved signage at Discharge Lounge |

| Improved patient info sheets and consent forms for patients on clinical trials |

| Have improved the quality of patient information brochures |

| Improved communication between the health service and the community |

| Advised on communication strategies to reach members of the public |

| Improved communication across organization and community networks |

| Improved awareness and understanding of service |

| Improved access and physical experience of hospital |

| Improved access to the hospital |

| Improved disability parking/access to hospital |

| Improved access for CALD communities |

The role of community representatives on committees

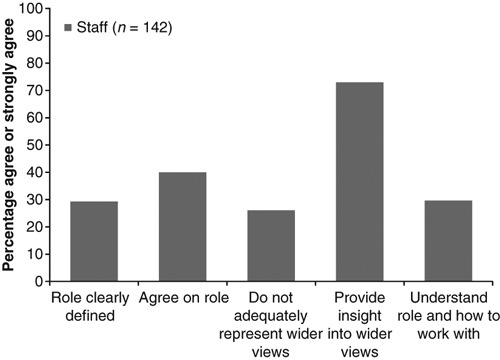

A number of attitudinal questions focussed on the views of respondents about the role of community representatives on health service committees. Figure 1 shows the percentage of staff who agree or strongly agree (4 and 5 on the Likert scale) with key statements about the role of community representatives included in the survey.

Figure 1.

The role of community representatives.

Most of the staff had positive attitudes about the capacity of community representatives to represent a wider view with most agreeing that community representatives provide insight into the wider views of patients and the community and < 30% agreeing with the statement that community representatives are not able to adequately represent the wider views of patients or the community. Only 40% of staff agreed that the health service and community representatives agree on the role of community representatives on committees and just under 30% agreed that health workers understand the role of community representatives on committees and how to work with them in an open manner.

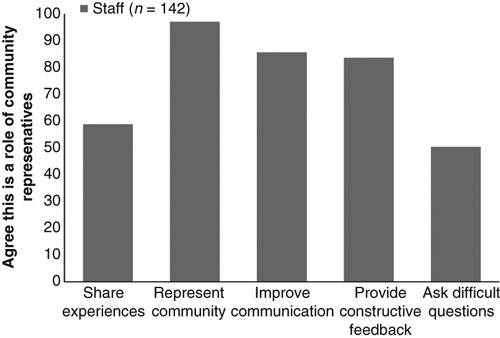

Figure 2 shows the percentage of staff who agreed with a particular role for community representatives on committees. The respondents could tick more than one option.

Figure 2.

Specific roles of community representatives on committees.

When asked about the specific roles of community representatives on committees most of the staff surveyed agreed that their role was to represent the community or patient perspective. Most agreed that the community representative’s role was to improve communication between the health service and the community and to provide constructive feedback. Some 59% agreed that the community representative’s role was to ask difficult questions and nearly 60% that their role was to share their experiences.

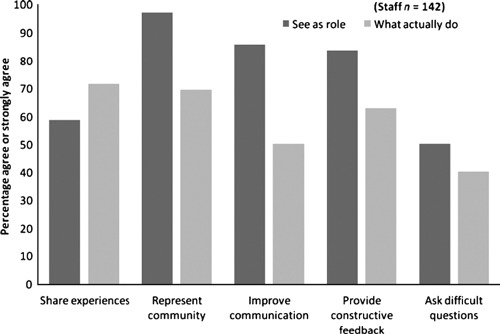

Figure 3 shows the percentage of staff who agreed with a particular role for community representatives on committees compared to the percentage who agreed that community representatives actually assumed a particular role on committees in practice. The respondents could tick more than one option.

Figure 3.

Roles of community representatives and what believe do in practice.

There were significant differences in the percentage of staff who agreed that particular roles were appropriate for a community representative and the percentage that agreed that they took on that particular role in practice. Significantly more staff believed community representatives shared their experiences than thought should share their experiences as part of their role (P = 0.02). Significantly more staff thought community representatives should represent the community than thought community representatives actually did this in practice (P = < 0.001). The same finding and level of significance was found for improving communication and providing constructive feedback.

Discussion

This study makes important new contributions to our understanding of staff perceptions about the roles and effectiveness of community participation in health services as part of a formal Community Participation Program supported by a clear policy framework and structure, staff resources, training and support mechanisms. Staff responses overall in this survey to the roles they believe representatives should embrace compared with what they believe they actually do in practice highlights a mismatch between perception and reality.

Value and influence

Most of the staff surveyed had positive attitudes about the value and potential for influence of community representatives at their health service confirming other studies in different settings, 22 , 27 , 28 , 29 although the present work represents a larger‐scale survey. In the research we asked for specific examples of the impact of community representatives at the AHS. Nearly two‐thirds of staff gave examples, many of which were related to service re‐design or service delivery. The impacts identified have the potential to translate to improved quality of care although this was not measured in the current study and is difficult to attribute to participation by the community or any other single measure undertaken in health services. 3

A novel finding in this study was the reference by many staff to the positive changes to the conduct of the meetings that representatives attended. Earlier work has found lay board members of Primary Care Groups and Trusts saw their role as restricted to reducing jargon. 7 Positive changes to meeting conduct may be a by‐product of the ‘over‐seeing’ role of representatives identified by Litva et al. 44 and while it only directly relates to a change to the process of discussion and debate we would argue it is a positive precursor to transparency and accountability. Thus the effectiveness of community participation on health service committees needs to be viewed broadly at this AHS and in the broader policy arena, including the impact of community representatives on the conduct of meetings, in addition to the more narrow view of effectiveness in terms of direct impacts on decision‐making and health service delivery.

Most of the staff held positive attitudes about the capacity of representatives to embody or advocate a wider view that included the perspectives of other patients and the broader community. This view is in line with the stated aims of the CPP and the roles outlined as expected of representatives in the Framework. However, this finding is in contrast to qualitative studies in clinical governance in the UK where concern has been expressed by some consumers involved that they should be expected to represent anyone other than themselves. 7 , 44 There is much debate about the capacity of health service users who sit on committees to be representative of others. 5 , 12 , 45 , 46 , 47 Although community representatives were involved in the development of the CPP Framework, the notion that at least some of the roles they take on may be contested at this AHS is supported by the remainder of the study findings discussed below.

Lack of clarity and agreement about roles

A major challenge identified from this study is the large percentage of staff who did not agree that the role of community representatives was clearly defined or that staff understand the role or how to work with community representatives on committees. Around half of the respondents also did not believe the health service and community representatives agree on the role of community representatives on committees. Lack of role clarity and disagreement between different stakeholder groups about roles has been raised previously in qualitative studies, 7 , 17 , 19 , 48 , 49 but this large scale survey of health staff across an AHS suggests such views may be widespread among staff who sit on committees with community representatives.

A leading health policy organization in the UK has lamented the failure of policy makers to define what public involvement in health care means and why it is needed. 5 Hogg and Williamson have further argued that ‘the different roles that lay people play need to be explicitly defined in order for their contributions to be realized’ 33 (p. 2). However, there are few empirical studies, and none with a large enough sample to suggest transferability, that explore the perceived occurrence and acceptance of different roles among different stakeholder groups, including health staff. We found only two qualitative studies which shed some light on possible roles.

Pickard et al. found lay board members of Primary Care Groups and Trusts perceived their role as ensuring the views of their locality are heard, that the Trust or Group’s operation is accountable and honest, that the language is transparent and to inform the public of the role and activities of these organizations. 7 However, they concluded that the role of lay members lacked clarity. A recent series of focus groups in the UK found that users saw different roles for themselves based on their different health care experiences as patients, citizens or advocates. 44 The range of roles identified included ‘overseeing’ the process of decision‐making, feeding back information to the community, being a partner in decision‐making and protecting the wider interests of the local community by getting matters investigated or changed. Patients (current health service users) and citizens (with no direct experience of using health services) both saw their role as representing the wider community interest.

Further debate at this AHS and in the broader policy arena may be helpful in articulating the kinds of roles representatives should be expected to undertake and the training and support which may be needed if these expectations are to be realized. Lack of agreement about roles does not mean staff are right about their role expectations. The interests of consumers and health staff are not always aligned 33 and at times community representatives may see their role as raising issues that make staff uncomfortable. Disagreement between the two groups at some times is therefore expected and is likely to be beneficial in producing the kinds of impacts staff identified in this survey. Some roles and actions by community representatives may also be directly opposed by health staff as part of the power dynamics and shifts required to give consumers more of a voice in health services. Power is viewed as a central concept in the broader theorizing on community participation 21 , 50 , 51 and relinquishing power is often necessary by one group for another to gain power. 52 , 53 Such a power shift is unlikely to happen without some resistance on the part of the group who will lose power. 16 , 54 , 55

Representing the community

In questioning staff in more detail about the specific roles they believed community representatives should adopt it was found that representation of the community was a key role with which they largely agreed. Significantly more staff also thought representatives should represent the community than believe actually do this in practice raising the question of how realistic are staff expectations about the capacity of community representatives to always speak from a representative perspective. What constitutes representation and its importance has been a key feature of debate and discussion in the literature. 7 , 12 , 16 , 20 , 34 , 46 Some scholars have questioned the necessity for user involvement to be equated with representativeness in order to be legitimate and valuable. 21 , 47 Others have raised the problem of alignment of lay members with managers and professionals vs. the patient interest. 33

How others conceptualize representation sheds some light on the types of representation which may be expected by staff at this AHS. Pitkin 56 outlines a framework for the analysis of representation including three main views which are espoused:

-

1

Formal representation where formal devices are used to designate representation, such as elections

-

2

Descriptive representation where the representative is seen as similar to the ‘average’ person they represent

-

3

Symbolic representation where the participant may be seen, and may view themselves as symbolizing representation, but in fact have no formal constituency to call upon or be accountable to.

The third view is embraced by Contandriupoulos in his examination of public participation in health care: ‘legitimacy is not so much granted by formal or descriptive representation as by the (subjective) perception of “representativeness”’ 57 (p. 327). He also argues that there are often very weak formal representation procedures for most of what we call public participation in health care meaning the ability of the self‐designated ‘public’ representative to appear as a legitimate spokesperson is paramount.

The CPP framework states the need for community representatives to ‘represent collective views and concerns’ and stresses they are chosen to reflect as much as possible the diversity of the local community. This suggests that community members who participate are meant to be both symbolic and descriptive representatives, the latter more likely to be underlying staff views at this AHS. In the case of this AHS, perhaps the capacity to mobilize others and have links to several groups may be more appropriate for many who participate on committees and working groups 14 , 20 – a more ‘symbolic’ form of representation. Descriptive representation is likely to be particularly challenging in this AHS given its diversity of cultural and language groups. 18 However, attention is still needed to other mechanisms which can give voice to the more marginalized groups in this community, including more targeted consultations. 18

Providing a communication link

Most staff agreed that community representatives should provide a communication link between the health service and the community – a role that is often not widely promoted. A limited number of qualitative studies have identified the role of feedback to the community and its relation to the role of ‘overseeing’ and improving accountability. 7 , 44 The CPP aims to improve transparency and accountability underscoring the need to see the role of community representatives in some contexts as simply to listen and observe enabling them to feedback what they hear to the community, and when needed hold health services to account by raising issues from the community.

Sharing experiences

Around 60% of staff thought community representatives should share their experiences as part of their role. There was also a significant difference between perceptions and what staff say they observed, for example, over 70% of staff thought representatives shared their experiences on committees when < 60% thought they should do this as part of their role. The Framework clearly states that a role of the representative is to contribute the consumer or carer experience. However, staff views highlight that sharing experiences may be a source of conflict in health service meetings and in the ongoing relationship between staff and community representatives at this AHS as has been documented elsewhere. For example, a study of a cancer partnership project found there were tensions between staff and community members centred on the acceptability of sharing of personal experiences as part of their role. 46 Others in the literature acknowledge the limitations of experiential knowledge, but nevertheless argue that users can make important contributions from their own personal, non‐medical experience including asking questions that are outside health professionals’ frames of reference. 21 Tritter and McCallum further argue that sharing experiences may break down boundaries and help build understanding between lay and professionals and others have concurred that experiential knowledge and personal narratives can provide an important challenge to the agenda of the health service and can help in educating providers. 6 , 58

Providing constructive feedback

We found significantly more staff thought representatives should provide constructive feedback than believe do in practice. This more active role for community representatives requires a greater capacity and confidence to speak up in health service meetings where community representatives are out‐numbered by health staff. Only some community representatives may feel able to directly challenge health staff views and ask for changes in health service actions to improve the patient experience. Feedback may also not always be viewed by staff as constructive, but may have the desired effect in challenging health service practices and attitudes.

Conclusions

While it is obvious that increased training and support to staff and community representatives would improve the capacity and potential for influence of community participation at this AHS, this is not the only area for future attention. In fact some have questioned the view that ‘users’ can only be regarded as ‘experts’ when appropriately trained when they already bring considerable expertise from their own health care experiences. 21 Articulating a wider range of roles for community members on committees in a future revision of the Framework is needed. Further issues are raised by these findings. For example, providing constructive feedback and being able to represent the community more broadly may be attainable only by a minority of community members, removing them from the realm of the ordinary into that of the exceptional. Such a conclusion echoes the Catch‐22 of having to be ordinary to be representative, but by being ordinary being unable to be effective that Learmonth et al. argue is evident in the policy discourse of public involvement in the UK. 15

At this AHS there is a need for further work to demonstrate the value of community representatives’ personal experiences to staff. A clearer discussion of the purpose and value of these experiences should be outlined in the Framework and be a training focus for staff. Facilitating open debate and discussion between staff and community representatives about sharing experiences would also be an important action for community participation staff. Such open discussion could build staff understanding of their value and also help build the capacity of representatives to share their experiences more effectively so that they can be heard and acted upon within health services. A key focus for future research should also be the way in which experiences are shared and the contexts in which they are shared, not merely the sharing of experiences per se. What types of experiences are seen by staff and community representatives as valuable to share? How should they be communicated and in what contexts? Others have found personal experiences delivered too strongly can be perceived as a personal grievance compared with those delivered with moderation and focus as valid contributions. 46

The current study has explored staff attitudes to a range of roles for community representatives on committees providing insights into the scope of the challenges to be tackled in operationalizing and realizing the full benefits of community participation.

While the findings of this study may not be directly generalizable to other contexts and countries they will have some level of transferability and resonance for those working in other settings where community representatives sit on committees. The different roles examined in this study warrant further investigation in a range of contexts and with different stakeholder groups.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial or other relationship that may constitute a conflict of interest with respect to the research findings published in the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the health service staff and community representatives who participate in the CPP and who completed the survey. The involvement of the staff of the Community Participation Unit and the Community Participation Coordinators based at local health services was invaluable in the refinement of the survey instrument as well as ensuring the surveys were completed and returned. Our appreciation goes to Van Nguyen for assistance with analysis and Dr Niamh Stephenson and Elizabeth Harris for their valuable insights into revisions of the manuscript. The survey instrument was adapted by the School of Public Health and Community Medicine, UNSW and the Community Participation Unit, South West Sydney in 2008 from the Evaluation Questionnaires in NSW Health (2000), Health Councils in Rural NSW, Phase One Evaluation, March–August 1999.

References

- 1. Bastian H. Speaking up for ourselves. The evolution of consumer advocacy in health care. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 1998; 14: 3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Charles C, DeMaio S. Lay participation in health care decision making: a conceptual framework. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 1993; 18: 881–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crawford MJ, Rutter D, Manley C et al. Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ, 2002; 325: 1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Entwistle VA. Public involvement in health service governance and development: questions of potential for influence. Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Florin D, Dixon J. Public involvement in health care. BMJ, 2004; 328: 159–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fudge N, Wolfe CDA, McKevitt C. Assessing the promise of user involvement in health service development: ethnographic study. BMJ, 2008; 336: 313–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pickard S, Marshall M, Rogers A et al. User involvement in clinical governance. Health Expectations, 2002; 5: 187–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salter B. Patients and doctors: reformulating the UK health policy community? Social Science & Medicine, 2003; 57: 927–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. CFC . Improving Health Services through Consumer Participation: A Resource Guide for Organisations. Consumer Focus Collaboration; Department of Public Health at Flinders University, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Butler A. Consumer Participation in Australian Primary Health Care: A Literature Review. Canberra: National Resource Centre for Consumer Participation in Health, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Draper M. Involving Consumers in Improving Hospital Care: Lessons from Australian Hospitals. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Forster R, Gabe J. Voice or choice? Patient and public involvement in the National Health Service in England under New Labour. International Journal of Health Services, 2008; 38: 333–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daykin N, Evans D, Petsoulas C, Sayers A. Evaluating the impact of patient and public involvement initiatives on UK health services: a systematic review. Evidence and Policy, 2007; 3: 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jewkes R, Murcott A. Community representatives: representing the “community”? Social Science & Medicine, 1998; 46: 843–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Learmonth M, Martin GP, Warwick P. Ordinary and effective: the Catch‐22 in managing the public voice in health care? Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 106–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rutter D, Manley C, Weaver T, Crawford MJ, Fulop N. Patients or partners? Case studies of user involvement in the planning and delivery of adult mental health services in London. Social Science and Medicine, 2004; 58: 1973–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kidd S, Kenny A, Endacott R. Consumer advocate and clinician perceptions of consumer participation in two rural mental health services. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 2007; 16: 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nathan S. Consumer participation: the challenges to achieving influence and equity. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 2004; 10: 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perkins D, Senior K, Owen A. Mere tokenism or best practice: The Illawarra Division of General Practice Consumer Consultative Committee. Australian Journal of Primary Health Interchange, 2002; 8: 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Church J, Saunders D, Wanke M, Pong R, Spooner C, Dorgan M. Citizen participation in health decision‐making: past experience and future prospects. Journal of Public Health Policy, 2002; 23: 12–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tritter JQ, McCallum A. The snakes and ladders of user involvement: moving beyond Arnstein. Health Policy, 2006; 76: 156–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carr BJ. Making the best of consumer participation. Journal of Quality in Clinical Practice, 2001; 21: 37–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Medicare Australia . About Medicare Australia, 2009. Available from: http://www.medicare.gov.au/about/index.jsp, accessed 29 April 2009.

- 24. NRCCPH . Feedback, Participation and Consumer Diversity: A Literature Review. Canberra: NRCCPH, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pickin C, Popay J, Staley K, Bruce N, Jones C, Gowman N. Developing a model to enhance the capacity of statutory organisations to engage with lay communities. Journal of Health Services & Research Policy, 2002; 7: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Putland C, Baum F, MacDougall C. How can health bureaucracies consult effectively about their policies and practices? Some lessons from an Australian study. Health Promotion International, 1997; 12: 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- 27. al‐Mazroa Y, al‐Shammari S. Community participation and attitudes of decision‐makers towards community involvement in health development in Saudi Arabia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1991; 69: 43–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Milewa T. User participation in service planning. A qualitative approach to gauging the impact of managerial attitudes. Journal of Management in Medicine, 1997; 11: 238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Monahan A, Stewart DE. The role of lay panelists on grant review panels. Chronic Diseases in Canada, 2003; 24: 70–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nathan S, Harris E, Kemp L, Harris‐Roxas B. Health service staff attitudes to community representatives on committees. Journal of Health Organisation and Management, 2006; 20: 1477–7266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bryant J, Saxton M, Madden A, Bath N, Robinson S. Consumers’ and providers’ perspectives about consumer participation in drug treatment services: is there support to do more? What are the obstacles? Drug and Alcohol Review, 2008; 27: 138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McCann TV, Baird J, Clark E, Lu S. Mental health professionals’ attitudes towards consumer participation in inpatient units. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2008; 15: 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hogg C, Williamson C. Whose interests do lay people represent? Towards an understanding of the role of lay people as members of committees. Health Expectations, 2001; 4: 2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gorsky M. Community involvement in hospital governance in Britain: evidence from before the National Health Service. International Journal of Health Services, 2008; 38: 751–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hogg CNL. Patient and public involvement: what next for the NHS? Health Expectations, 2007; 10: 129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Health Issues Centre . Participate in Health. Victoria: Health Issues Centre, 2009. Available from: http://www.participateinhealth.org.au/index.asp, accessed 29 April 2009.

- 37. Gregory J. Consumer Engagement in Australian Health Policy Australian Institute of Health Policy Studies, 2008. Available from: http://healthpolicystudies.org.au/component/option,com_docman/task,cat_view/gid,55/Itemid,145/, accessed 9 February 2010.

- 38. Australian Council on Healthcare Standards . National Report on Health Services Accreditation 2003–2006. Sydney: Australian Council on Healthcare Standards, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johnson A, Silburn K. Community and consumer participation in Australian health services: an overview of organisational commitment and participation processes. Australian Health Review, 2000; 23: 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sydney South West Area Health Service . Sydney South West Area Health Service Statutory Annual Report 2006/07: Sydney South West Area Health Service, 2007. Contract No.: April 29 2009.

- 41. Sydney South West Area Health Service . Community Participation Framework. Liverpool, NSW: Sydney South West Area Health Service, 2006. Available from: http://swsahs.nsw.gov.au/corpinfo/commpart/default.asp, accessed 15 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42. NSW Health . Health Councils in Rural NSW, Phase One evaluation, March–August 1999. Sydney: NSW Health, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43. SPSS . SPSS Statistics Version 17 for Windows. Chicago: SPSS Inc, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Litva A, Canvin K, Shepherd M, Jacoby A, Gabbay M. Lay perceptions of the desired role and type of user involvement in clinical governance. Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Crawford M, Rutter D. Are the views of members of mental health user groups representative of those of ‘ordinary’ patients? A cross‐sectional survey of service users and providers. Journal of Mental Health, 2004; 13: 561–568. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sitzia J, Cotterell P, Richardson A. Interprofessional collaboration with service users in the development of cancer services: The Cancer Partnership Project. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 2006; 20: 60–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Williamson C. The rise of doctor–patient working groups. BMJ, 1998; 317: 1374–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Quennell P. Getting their say, or getting their way? Has participation strengthened the patient “voice” in the National Institute for Clinical Excellence? Journal of Management in Medicine, 2001; 15: 202–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van Wersch A, Eccles M. Involvement of consumers in the development of evidence based clinical guidelines: practical experiences from the North of England evidence based guideline development programme. Quality in Health Care, 2001; 10: 10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arnstein SR. Ladder of citizen participation. AIP Journal, 1969; 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johansen M, Oliver S, Oxman AD. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy, research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52. Labonte R. Participation in health promotion: the ‘Hardware’ and the ‘Software’ In: Labonte R. (ed.) Power, Participation and Partnerships for Health Promotion. Victoria, Australia: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, 1997: 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Labonte R. Mutual accountability in partnerships: health agencies and community groups. Promotion et Education, 1999; 6: 3–8, 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Williamson C. Reflections on health care consumerism: insights from feminism. Health Expectations, 1999; 2: 150–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Williamson C. The challenge of lay partnerships: it provides a different view of the world. BMJ, 1999; 319: 721–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pitkin HF. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Contandriopoulos D. A sociological perspective on public participation in health care. Social Science & Medicine, 2004; 58: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Brooks F. Nursing and public participation in health: an ethnographic study of a patient council. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 2008; 45: 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]