Abstract

Background Pharmacy practice is evolving according to general health‐care trends such as increased patient involvement and public health initiatives. In addition, pharmacists strive to find new professional roles. Clients’ expectations of service encounters at pharmacies is an under‐explored topic but crucial to understanding how pharmacy practice can evolve efficiently.

Objective To identify and describe different normative expectations of the pharmacy encounter among pharmacy clients.

Methods Q methodology, an approach to systematically explore subjectivity that retains complete patterns of responses and organizes these into factors of operant subjectivity.

Setting and participants Eighty‐five regular prescription medication users recruited at Swedish community pharmacies and by snowballing.

Results Seven factors of operant subjectivity were identified, and organized into two groups. Factors that emphasized the physical drug product as the central object of the pharmacy encounter were labelled as independent drug shopping; logistics of drug distribution; and supply of individual’s own drugs. Factors that emphasized personal support as desirable were labelled competence as individual support; individualist professional relations, just take care of me; and practical health‐care and lifestyle support.

Discussion and conclusions The systematic Q‐methodological approach yielded valuable insights into how pharmacy clients construct their expectations for service encounters. They hold differentiating normative expectations for pharmacy services. Understanding these varying viewpoints may be important for developing and prioritizing among efficient pharmacy services. Clients’ expectations do not correspond with trends that guide current pharmacy practice development. This might be a challenge for promoting or implementing services based on such trends.

Keywords: normative expectations, pharmacy encounter, pharmacy practice development, pharmacy services, Q‐methodology

Background

As the pattern of disease shifts from acute to chronic conditions and the ‘knowledge gap’ shrinks between professionals and the public, health‐care delivery is also changing. Health‐care professionals need to change their practice to adapt to these changes. 1 In community pharmacy practice, this change is further accentuated because pharmacists are actively seeking new roles. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Thus, we see a proliferation of novel services, 2 developed and inspired by a number of societal trends, including an increased focus on patient involvement in health‐care and public health initiatives.

The concept of pharmaceutical care underscores the importance of patient‐centred care; with such care, the focus is on medicine use by patients rather than only on the products. 6 , 7 , 8 Pharmacies that offer a wider range of services targeting public health are predicted to enter a growing market 9 and that role is commonly endorsed by public bodies. 2 , 3 , 5 , 10

Professional views on various pharmacy services have been previously explored. 11 , 12 , 13 It is not certain, however, that these professionally driven trends correspond to what pharmacy clients themselves want. Clients potentially vary in their preferences for involvement in health care, because of both personal traits and contextual factors. 14 , 15 Some may pay more attention to the process itself, i.e. the quality of the interaction with the pharmacist, than its possible outcomes, i.e. improved health. 16 Other groups of clients may have very different expectations regarding the pharmacy encounter.

The client (or patient) viewpoint is increasingly the subject of extensive study throughout health care. 17 , 18 Subjective expectations of pharmacies and pharmacy services will trigger (or not trigger) action among pharmacy clients to seek help by a pharmacist or not, affect encounter satisfaction, and influence the decision as to what pharmacy to visit. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 Advertising and performing services that appeal to the ideals that clients hold will raise the expectations for future service encounters. 24 Clients’ low expectations for advice‐giving roles that pharmacists wish to embrace have been cited as an important barrier for efficient pharmacy practice development. 21 , 25 , 26 To provide successful services, it is important to foster a perception of long‐term quality by changing those expectations. This could involve focusing unclear expectations, revealing implicit expectations or calibrating unrealistic expectations. 27 Therefore, it is important to understand the normative expectations of pharmacy clients to achieve efficient and acceptable services that will advance pharmacy practice overall.

With the exception of studies on patient satisfaction, the literature reporting pharmacy clients’ views is limited, 28 , 29 although expanding. 30 By identifying normative expectations of pharmacy services for different client groups, future services might capitalize on those expected social interactions. 30 , 31 , 32 To be useful in service development, those client‐perceived ideal situations need to be explicitly constructed, rather than suggesting the vague opinion that pharmacy should be better at everything.

There are some smaller business‐oriented studies of demand and individual pharmacy services. 33 , 34 However, there has been limited systematic research to describe the complex reality of what people want and expect from their pharmacy encounters. 10 Tinelli et al. 35 explored the patient perceived pharmacist role with a focus on prescribing services. They found that although patients value pharmacist contributions to care, they are generally resistant to change. Porteous et al. 36 showed that community pharmacy is a valued source of professional advice on minor illness. Both of these studies employed the discrete choice technique and focused on the Scottish population. Hedvall and Paltschick 37 investigated, using factor and cluster analyses of questionnaire responses, what kind of services different pharmacy client groups wanted to facilitate pharmacy’s transition from product‐ to service‐oriented enterprises. Four groups were identified: the contented pharmacist‐dependent client, the independent client, the information seeker and the discontented client. Apart from being nearly 20 years old, their findings are limited by the scope of the study and the questionnaire methodology employed.

Aims

This study aimed to identify and describe different normative expectations of the pharmacy encounter among pharmacy clients.

Methods

Q methodology was chosen for this study, as a recognized scientific method of studying subjectivity. Although most authoritative texts maintain that Q methodology belongs to the quantitative research tradition, it involves some traits commonly associated with qualitative research. These are, in particular, the focus on the single case and an explicit reliance on subjective interpretation. 38 , 39 , 40 Q methodology is concerned with exploring individual holistic views, rather than measuring various ‘traits’ held by the participants. This concern for the single case has an impact on the methods for recruiting of participants. There is no necessity for a representative random sample, and it is acceptable to use a pragmatic approach (as in this study). Also, as focus is on the views, rather than the people, even a single case is considered as important as many. 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 Q methodology has been used, for example, to study the perceived meaning of health‐related quality of life, 42 preferences for hypertension management, 43 understanding chronic pain, 44 understanding the care needs among people with intellectual disabilities 45 and youth attitudes about healthy lifestyles. 46 A full recount of the methodological considerations underpinning Q methodology is beyond the scope of this article. The reader is referred to original works by Stephenson 40 and Brown, 38 as well as more recent texts that analyse and summarize the methodology. 39 , 41 , 47 , 48 , 49

Procedure

In Q methodology, a number of participants rank‐order a number of statements (Q sample) in a forced distribution according to a specific condition of instruction. The sorting is performed according to the ‘psychological significance’ that each statement has for that individual. 40 The sorts are then subjected to a by‐person factor analysis, 50 , 51 in which the individual response patterns are kept intact. 49 , 52 The sorts, rather than the items, are grouped together into ‘factors of operant subjectivity’ (henceforth shortened to factors). Participants contribute to all factors by varying degrees, and each factor corresponds to a specific subjective point of view. 41

To visualize each factor, an ‘ideal’ Q sort, called a factor array, is produced by comparing individual sorts created by participants who load significantly on that factor (P < 0.05) and only slightly on other factors. 39 In this study, this was operationalized as occurring when the squared factor loading on the significant factor accounted for at least half of the sum of squared factor loadings across all factors extracted. The sorts thus selected to visualize the factor arrays are called factor exemplars. The factors are primarily interpreted by subjective judgement of their respective factor arrays. 38

Q sample generation

The first author identified three relevant dimensions in an unsystematic review of 54 articles on the perception, nature and effects of pharmacy services (literature list available as Data S2): how participants assess the quality of pharmacy services, what they consider to be the ideal object in focus of the pharmacy encounter and what power relationship is desirable. In all dimensions, three possible modes were identified. The final proposed model is shown in Table 1. Preliminary statements, based on the literature, were generated according to the structured factorial design of the model, to achieve a comprehensive coverage of the topic. 41

Table 1.

The dimensional model for generating the Q sample

| Dimensions | Possible modes |

|---|---|

| Quality assessment base | Technical |

| Process oriented | |

| Result oriented | |

| Focus of pharmacy encounter | Drugs |

| Drug use | |

| Health care/lifestyle | |

| Power relationship | Pharmacist driven |

| Collaborative | |

| Client driven |

Each statement thus represented a combination of the dimensional modes. All possible combinations of the 3 × 3 model stipulated a total of N*27 statements. To get a suitable amount of statements for the sorts, N was set to two, resulting in 54 statements. 53 Examples of the final statements are found in Table 2, and the full list is available as Data S3.

Table 2.

Examples of statements in the Q sample

| Statement | Assignment to dimensional modes |

|---|---|

| The pharmacy is a store where you buy drugs, and just like in other stores, the customer is always right | Technical – drugs – client driven |

| The pharmacist gives spontaneous advice about how to use my drugs | Process oriented – drug use – pharmacist driven |

| My discussion with the pharmacist results in concrete advice about a healthy life | Result oriented – health‐care/lifestyle – collaborative |

Although the exact sampling of statements have been shown to be of lesser importance in Q methodology compared to questionnaires, 54 they must still be understood. The preliminary statements were given to five research colleagues at the Department of Pharmacy, Uppsala University to check their face validity. The dimension and mode definitions, as well as the statements, were revised in the light of their comments in an iterative process (two extra raters in the first and second round and one in the last). Following a small (n = 2) pilot with two patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria (a 65‐year‐old female and a 24‐year‐old male), recruited in the same manner as described for other participants below, the Q sample and the sorting instructions were slightly revised.

Participant recruitment

Pharmacy clients were mainly recruited at four pharmacies in Uppsala, Sweden, which were purposely selected to cover a wide range of potential participants. They varied in size and the profile of revenues (importance of medical products vs. other goods), two were located in the city centre and two in the outskirts of the city, two were located in shopping malls (one in the city centre) and one in conjunction to a health‐care centre. For an outline of the Swedish community pharmacy system, please refer to Westerlund and Björk. 55 Clients were approached by a researcher after collecting prescriptions at the pharmacies and given verbal and written information about the study. To be considered for inclusion, clients had to be 18 years old, have a condition requiring drug treatment for at least 3 months, to be able to understand Swedish and be able to read the size 14 font used in the study. As Q methodology is concerned with the description of single cases, rather than analysing frequencies, a pragmatic sampling approach is acceptable. 41 Consequently, a small number of participants were also recruited by snowballing. Clients who considered participating gave contact information to the researcher, allowing time for further reflection on their participation. The researcher contacted the participants later to arrange a time and location for the study.

Conduct of study

The Q sorts were performed individually. However, to improve efficiency, groups of up to seven people did their sorts at the same time and in the same room. At the participants’ request, the sorts could also be performed individually with the researcher, either at their homes or at the University premises. The study was conducted between February and November 2008.

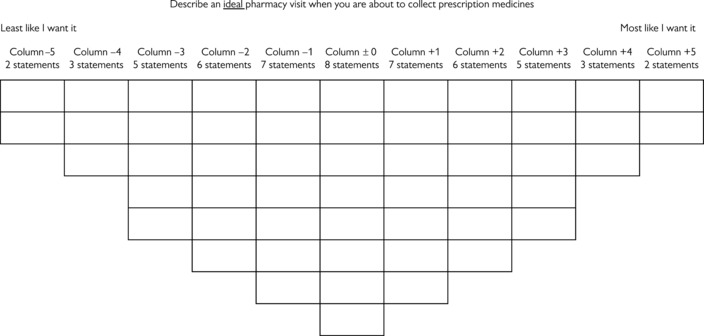

A researcher (TR or KWT) explained the study to the participants, who were asked to sort the 54 statements, printed on cards, into a forced distribution shown in Fig. 1, under the condition of instruction: ‘Describe an ideal pharmacy visit when you are about to collect prescription medicines’ (underscore in original).

Figure 1.

Forced distribution used in study.

The practical instructions for performing the Q sorts were derived from McKeown and Thomas, 41 and Donner. 53 It was emphasized that participants should move statements around until they were satisfied. A questionnaire was also administered to measure characteristics of the participants, including age, gender, self‐rated health, living situation, main language, educational level, economic vulnerability, experience of health‐care work, beliefs about medicines, medication adherence, drug treatment and pharmacy use. The results are important to judge usefulness of our findings in practice, but as they concern attributes of the participants rather than the factors, they are reported elsewhere. 56

Analysis process

All sorts were factor analysed, using the principal components technique and the Software PQMethod, a program especially designed for analysing studies using the Q technique. 57 Twenty‐three factors with an eigenvalue above one were identified. These many factors would be difficult to interpret though, and each factor would explain very little of the total variance in the material. To get a smaller and more useful number of factors, we followed the suggestion of Brown to rotate seven factors (the rationale for this is lengthy, and found in Brown, p. 223 onwards) and drop factors that were impossible to interpret. 38 Varimax rotation was performed, which is suitable for exploratory work. 58 Each factor thus derived represented a distinct viewpoint of the participants. Components of the factors may seem similar, but they are placed in a different context for each factor. 38 , 40

The factor arrays were interpreted by looking at the relative weight (factor scores) put on individual statements in the factor arrays, especially highly negative or positive values. As we used a theoretical model, statistical testing can be used to facilitate interpretation. 38 As the tentative model in Table 1 is not validated, however, the statistical findings are considered only supporting information rather than definitive results. The interpretation of factor arrays was performed independently, in Swedish, by two of the authors (TR and SKS). No disagreements arose and the interpretations complemented each other. Final interpretation was decided by a consensus discussion between the interpreting authors. The resulting factors were ordered thematically to facilitate presentation.

Ethical considerations

In Sweden, at the time the study was conducted, ethics committee approval was not required for studies of this type. Nonetheless, the researchers considered ethical aspects both before and when conducting the study. The participation was voluntary, without coercion or negative consequences for non‐participants. Participants had to give informed consent to participate. The individual responses are unidentifiable in the final material.

Results

In all, 555 pharmacy clients were approached, 151 information leaflets were given to clients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were interested in participating, and 90 clients participated. Five sorts were excluded from analysis, as the participants did not follow the instructions. Eighty‐five sorts (54% of those receiving an information leaflet) were submitted to factor analysis. Forty‐eight (56%) of the participants providing eligible sorts were female. Data on age and educational level were documented for 84 participants, with a mean age of 61 years (range 23–90) and 57 (67%) having a University degree.

The seven extracted and rotated factors accounted for 54.4% of the variance. Thirty‐eight of the 85 sorts were defined as factor exemplars. Basic characteristics of the factors are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Varimax‐rotated factors

| Factor | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance explained (%) | 12 | 11 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| Number of factor exemplars | 12 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

The seven factors were labelled and thematically grouped as shown in Table 4. In total, two broad groups of participants emerged, those who primarily wanted the drug product to be the focus of the pharmacy visit and those who were mainly concerned with personal support during the visit.

Table 4.

Factor structure

| Group | Factor | Label |

|---|---|---|

| Group A: primarily want the drug product in focus | I | Independent drug shopping |

| II | Logistics of drug distribution | |

| III | Supply of individual’s own drugs | |

| Group B: mainly concerned with personal support | IV | Competence as individual support |

| V | Individualist professional relation | |

| VI | Just take care of me | |

| VII | Practical health‐care and lifestyle support |

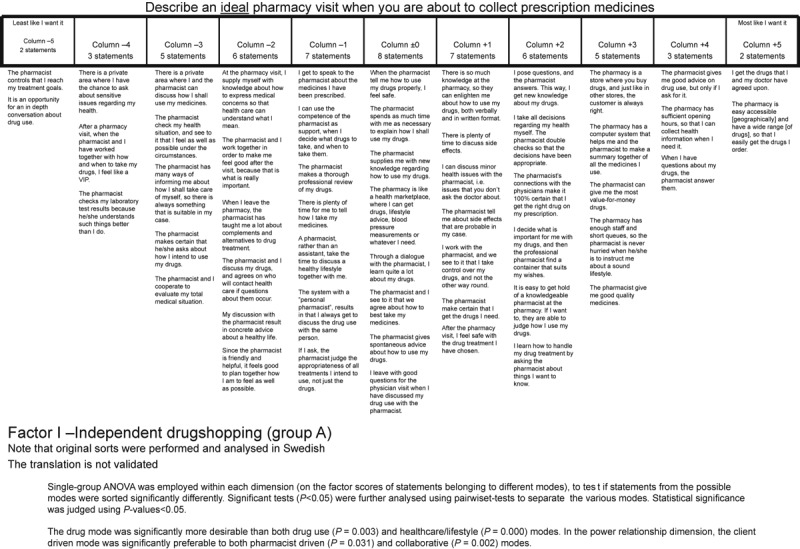

In the results section, only the interpretation of the data is presented. Figure 2 shows, as an example, the raw factor array and statistical test result for Factor I. Data for the remaining factors are available as Data S1.

Figure 2.

Example of factor array and statistical test results (Factor I).

Group A: primarily want the drug product in focus

The first group contain three factors that emphasize the physical drug product as the central object of an ideal pharmacy encounter, although they differ in other respects. While some stress the independent role of the pharmacy customer, others focus on the tangible logistics of the pharmacy as a centre for drug distribution. Others emphasize a desire to have their own drug treatment as a focal point of the interaction and a rejection of health‐care or lifestyle services.

Factor I – independent drug shopping

The number of factor exemplars for Factor I was 12. Factor I represented a highly independent viewpoint, which stressed easily accessible drugs of good quality that are good value for money. The pharmacy was portrayed as a store like other stores. Drugs should be easily accessible at the pharmacy, and the pharmacist should be able to answer questions or give advice, but only when they were asked to do so. However, in the ideal pharmacy encounter, Factor I exemplars wanted the pharmacist to avoid time‐consuming discussion or assessments. They did not want to be controlled by the pharmacists, nor did they want the pharmacist to perform independent clinical tasks, such as evaluating treatment goals or checking laboratory values. The pharmacy encounter was not considered an opportunity for in‐depth counselling, and this could possibly be why Factor I exemplars reported no need for private counselling areas.

Factor II – logistics of drug distribution

The number of factor exemplars for Factor II was eight. The ideal pharmacy encounter, according to Factor II exemplars, was similar to a service encounter at a centre for drug distribution. The logistics of supplying the right pharmaceutical product of good quality was central. Traditional service components, such as having good accessibility and short waiting time, were also valued by those loading on this factor. The right product was the one prescribed by the physician, and pharmacy was seen as an adjuvant, rather than independent function within health care. The pharmacist should also answer questions and explain the product and its side‐effects. This information should be transferred from pharmacist to patient rather than produced in dialogue. Factor II exemplars did not want to make their own health‐ or drug‐related decisions or possibly, rejected labelling their actions as decisions. In any case, they did not want to discuss their decisions with the pharmacist.

Factor III – supply of individual’s own drugs

The number of factor exemplars for Factor III was six. First and foremost, Factor III exemplars wanted a good‐quality drug product that had been negotiated with the physician, and they wanted it in a suitable package. A special emphasis was put on statements concerning the individual drug products used by the factor exemplars themselves, rather than drugs in general. In addition, they wanted knowledge about their drugs and how to use them, and they did not mind asking for such information. They were similar in many ways to Factor II exemplars, but stressed that pharmacy should not be business‐oriented. In addition, health‐care‐ or lifestyle‐related statements were more forcefully rejected by Factor III exemplars.

Group B: mainly concerned with personal support

The second group contains four factors that emphasized that the pharmacy encounter should provide the client with some form of personal support. The nature of that support varied between individual factors. For example, one factor focused on learning and empowerment, while another emphasized that pharmacy practice should be organized in a way to enable personal support. This group also contained a passive viewpoint and a factor that looked for alternative health care and lifestyle support.

Factor IV – competence as individual support

The number of factor exemplars for Factor IV was four. According to Factor IV exemplars, the competent pharmacist should offer individually designed support and knowledge about drugs and drug use. They should empower the client by both helping them to find relevant questions for their physicians to answer and supplying knowledge about medical terminology. Factor IV exemplars expressed a desire for knowledge in general and knowledge about side‐effects in particular. In spite of this, Factor IV did not particularly emphasize statements concerning the exemplars feeling safer or more secure as a result of the pharmacy visit. Similar to Factor II exemplars, they did not want to make health‐related decisions on their own. According to Factor IV exemplars, issues of health should not be the focus of the pharmacy encounters, and they did not want private counselling areas.

Factor V – individualist professional relations

The number of factor exemplars for Factor V was three. Factor V exemplars described an ideal pharmacy encounter more from the perspective of its structural prerequisites than what actually happened or what outcomes it produced. Privacy and personal contact were central concepts, and the pharmacy services should focus on side‐effects and convey the feelings of safety and security and a professional assessment of drug use. The idea of a traditional customer/store relationship did not appeal to Factor V exemplars, and they did not want the pharmacist to control treatment goals or laboratory values. Although stressing the importance of a personal contact, the pharmacy was not the site for every kind of health‐related services. For example, Factor V exemplars were the most critical of the concept of the pharmacy treating minor ailments.

Factor VI – just take care of me

The number of factor exemplars for Factor VI was two. Factor VI exemplars held a positive attitude towards the pharmacist and their competence. They valued friendliness on the part of the pharmacist and wanted them to take their time in providing services. This was the only factor to score positively on statements about the pharmacist giving spontaneous advice or asking questions about drug use. They also expressed a desire to have their drugs and drug use controlled by the pharmacist. Overall, they seemed to like all statements that implied that the pharmacist should ensure that something was carried out. Factor VI exemplars did not want the pharmacy to be reduced to a store or marketplace. Many statements suggesting some form of dialogue‐like interaction with the pharmacist scored negatively.

Factor VII – practical health‐care and lifestyle support

The number of factor exemplars for Factor VII was three. These factor exemplars rated accessibility, both geographical, and in terms of short waiting time and good opening hours, very highly. Most striking, however, was the ratings of statements concerning health, lifestyle or feeling good. Factor VII exemplars wanted a discussion about health, minor ailments and alternative treatments and support in both lifestyle issues and taking care of themselves. They did not think that they were always right or should make their own health‐care decisions independently. The pharmacy was considered as something disconnected from other health‐care services.

Discussion

In this study, we have systematically explored different normative expectations of pharmacy encounters. A model based on theory and earlier findings guided our enquiries, but the methodology employed allowed interpretation beyond the framework of that model. Thus, we believe that we have been able to demonstrate a more elaborate image of clients’ normative expectations of pharmacy services than previously achieved. This could be useful for understanding the pharmacy service market and developing services accordingly. Using a structured factorial design, we ensured a sufficient coverage of the relevant outcome space and forced the participants to prioritize between different constructs. We restricted the participants from merely expressing that they wanted everything, which is valuable when developing novel pharmacy services, when prioritization has to take place.

Differences between factors

Meeting the expectations of pharmacy clients from the different groups may require different professional approaches, different structural organization of the pharmacies and the development of different competencies. Understanding similarities between factors is important in practice development. For example, clients who hold views similar to those described in group A could be well served by a variety of drug distribution solutions, possibly connected to on‐demand information services, while group B is more dependent on the physical pharmacy environment and the professionals working there. Still, understanding that these similarities are presented in different contexts for different factors might help explain how different clients value different services. While a degree of individualization of pharmacy encounters already exists, 59 our findings may help pharmacy staff to make informed choices about what strategy would be useful in a particular case.

Focus of expectations

Several factors did acknowledge drugs as being central to the pharmacy services, but no one has particularly emphasized pharmacies working with drug use as a central desired concept, although they are not opposed to the idea. Likewise, none of the subjective views revealed in this study described desired services in terms of high‐quality outcomes. While contrasting with an outcomes‐oriented focus of evidence‐based pharmacy practice, this is in line with previous findings showing that helpfulness and competent image of the pharmacies are valued at least as much as final outcomes. 16 , 28 Such outcomes might be taken for granted, or judged as impossible to assess for the individual.

While Factor VII is the only identified viewpoint that shows a real interest in pharmacy as a health‐care and lifestyle arena, this is in addition to, and not in conjunction with other health‐care providers. Our data cannot identify the reasons for this, but arguably these individuals do not trust the existing health‐care system for some reason. Consequently, pharmacy, which is considered something outside that system, is seen as an alternative to get their health care needs filled. Previously, it has been shown that pharmacists are mainly seen as experts on drugs, not health and illness, and pharmacists’ advice are more accepted when connected to drug supply. 25 , 26

Client and pharmacist involvement

Constructs like consumerism 60 and service management discourse 61 predict an increasing involvement of the client in all aspects of care, which in turn will affect expectations as well. It is easy to speculate that such trends would be reinforced by current changes in the Swedish pharmacy market (The state monopoly was about to be abolished. This actually happened in July 2009). However, as described in the Background, pharmacists are seeking new roles. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 If they successfully claim that a specific expertise is the professional domain of the pharmacists, pharmacy users’ actual and expected involvement will decrease in those areas. This study does not reject the possibility of any of these developments, as there are Factors pointing in both directions.

Factor VI, for example, shows an interest in having the pharmacist involved in their care. Yet the factor exemplars seemed reluctant to share personal information with the pharmacist. Whether this represents a passive viewpoint, or reflects an expectation of pharmacists to show caring behaviour without background information, is unclear. Factor I by comparison clearly emphasizes the involvement of clients and reduces the involvement of pharmacists to being an on‐demand resource.

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. Contextual factors affect how pharmacy is viewed by their clients, 62 , 63 and this might affect expectations and perceived need for various pharmacy services. The study was limited to four pharmacies in a relatively small region where pharmacies practice within the Swedish health‐care and pharmacy systems. Although person samples can be fairly small, 85 respondents are likely to be too few to make a comparison between the sites. 39 , 41 Taken together, it is likely that we have not discovered all relevant factors. Neither could we quantify the prevalence of factors. This was not our aim, however, and it does not jeopardize the validity of the factors actually identified.

Our condition of instruction was theoretical rather than experiential. Together with the relatively complex factorial design of the Q sample, this resulted in a cognitively demanding sorting task. This may be the main reason that the factors derived did not explain more than 54.4% of the total variation, despite the fact that our participants were fairly well educated (67% with academic degree compared to the national figure for Sweden of 22%), 64 which could be viewed as a proxy for a high cognitive ability. Still, a theoretical condition of instruction was necessary as we were aiming for future development of services, rather than to evaluate existing ones. The factorial design was used to facilitate service development as it introduced a forced prioritization among concepts. There is little evidence on the effect of education and/or cognitive ability on the ability to participate in a Q‐methodological study. Combes et al. 45 have shown it to be a feasible approach even among people with intellectual disabilities.

Types of expectations

The kind of expectations that create role orientation for pharmacy services will vary. 65 It is likely that statements sorted on the positive end of the distribution represent a situation that was ideal or at least close to that kind of expectations in analogy with typologies such as those described by Zeithaml et al., 23 Santos and Boote. 24 Likewise, statements sorted on the negative end were closer to the worst conceivable service. The complete factor arrays thus formed a norm against which the quality of service encounters could be measured. Realistic expectations and actual experience of pharmacy services will have an impact on how ideal encounters are described. 19 , 24 The reception of pharmacy practice changes that are more radical than anticipated is therefore difficult to forecast, based on our findings. Still, ideal expectations are more resistant to change than other types of expectations. 19 , 23 Therefore, our findings of varying expectations might inform marketing and information strategies for novel services.

Practical utility and further research

The groups and factors identified in this study are rather broad, and their application in patient‐level individual practice will require that people holding such views could be identified both swiftly and accurately. This issue is addressed in our report about the questionnaire findings, 56 although we recognize that further research is needed. Professionals also need to consider whether or not it is appropriate to encourage all of the expected encounter types. This issue touches upon the balance between allowing patient autonomy and providing optimal care.

Because of its focus on the single case, Q methodology is not particularly suitable for exploring the composition of people associated with a group, and even less so with the individual factors. The factors could be used for a more informed exploration of these issues using other research designs, to learn more about the practical utility of our findings. Such studies could include the prevalence of clients holding different viewpoints at different sites and the impact of actual expectations on ideal expectations. Understanding the prevalence of factors and the composition of clients in the various groups is important to estimate the potential reach and efficacy of services, two important dimensions to public health impact. 66 There are a number of facets that might warrant additional study, including but not limited to, beliefs about medicines, illness perception, medication adherence, cultural background and self‐reliance of clients.

Further research in this field should also focus at validating or disproving our findings in other settings, using different methodologies. The stability of factors over time and conditions is unknown, although in theory, ideal expectations change slowly. 23 , 24 The reliability of Q methodology itself is not yet certain and should benefit from further study. 38 , 45 , 48

Conclusion

Groups of pharmacy clients show different normative expectations for pharmacy services. Understanding the heterogeneity of these viewpoints is crucial for developing and prioritizing among efficient pharmacy services. Clients’ expectations did not correspond with trends that guide current pharmacy practice development. This may be a challenge in promoting such services or make them reach their full potential.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest have been declared.

Source of funding

Funding was provided by Apotekets Forskningsfond [Fund for Research and Studies in Health Economics and Social Pharmacy in Sweden, Stockholm, Sweden], (Tobias Renberg’s salary) and state funding (cost of project).

Supporting information

Data S1. The complete factor arrays, including results for statistical testing of the theoretical model.

Data S2. The literature list that informed the Q sample generation.

Data S3. The full list of statements (The Q sample).

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants whom without compensation devoted their time to this study.

References

- 1. Taylor D, Bury M. Chronic illness, expert patients and care transition. Sociology of Health and Illness, 2007; 29: 27–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harding G, Taylor K. Responding to change: the case of community pharmacy in Great Britain. Sociology of Health and Illness, 1997; 19: 547–560. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson S. Community pharmacy and public health in Great Britain, 1936 to 2006: how a phoenix rose from the ashes. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2007; 61: 844–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Traulsen JM, Bissell P. (9) Theories of professions and the pharmacist. The International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 2004; 12: 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anderson S. The state of the world’s pharmacy: a portrait of the pharmacy profession. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 2002; 16: 391–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical Care Practice – The Clinician’s Guide, 2nd edn New York: McGraw‐Hill, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Mil JF, McElnay J, de Jong‐Van den Berg LW, Tromp DF. The challenges of defining pharmaceutical care on an international level. The International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 1999; 7: 202–208. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Björkman IK, Bernsten CB, Sanner MA. Care ideologies reflected in 4 conceptions of pharmaceutical care. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 2008; 4: 332–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garfield S, Hawkins J, Newbould J, Rennie T, Taylor D. Greater Expectations: Pharmacy Based Health Care – The Future for Europe? London: School of Pharmacy, University of London, 2007; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krajic K, Pelikan J, Plunger P, Reichenpfader U. Health Promotion in Primary Health Care: General Practice and Community Pharmacy – A European Project. Vienna: Ludwig Boltzmann‐Institute for the Sociology of Health and Medicine, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Montgomery AT, Kälvemark‐Sporrong S, Henning M, Tully MP, Kettis Lindblad Å. Implementation of a pharmaceutical care service: prescriptionists’, pharmacists’ and doctors’ views. Pharmacy World and Science, 2007; 29: 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. George J, Pfleger D, McCaig D, Bond C, Stewart D. Independent prescribing by pharmacists: a study of the awareness, views and attitudes of Scottish community pharmacists. Pharmacy World and Science, 2006; 28: 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Södergard BMH, Baretta K, Tully MP, Kettis Lindblad ÅM. A qualitative study of health‐care personnel’s experience of a satellite pharmacy at a HIV clinic. Pharmacy World and Science, 2005; 27: 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Auerbach SM. Do patients want control over their own health care? a review of measures, findings, and research issues. Journal of Health Psychology, 2001; 6: 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fraenkel L, McGraw S. Participation in medical decision making: the patients’ perspective. Medical Decision Making, 2007; 27: 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holdford D, Schulz R. Effect of technical and functional quality on patient perceptions of pharmaceutical service quality. Pharmaceutical Research, 1999; 16: 1344–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosenthal GE, Shannon SE. The use of patient perceptions in the evaluation of health‐care delivery systems. Medical Care, 1997; 35: NS58–NS68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Popay J, Williams G. Public health research and lay knowledge. Social Science and Medicine, 1996; 42: 759–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boulding W, Kalra A, Staelin R, Zeithaml VA. A dynamic process model of service quality: from expectations to behavioral intentions. Journal of Marketing Research, 1993; 30: 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nau DP, Ried LD, Lipowski E. What makes patients think that their pharmacists’ services are of value? Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association, 1997; 37: 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schommer JC. Patients’ expectations and knowledge of patient counseling services that are available from pharmacists. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 1997; 61: 402–406. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kucukarslan S, Schommer JC. Patients’ expectations and their satisfaction with pharmacy services. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association, 2002; 42: 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zeithaml V, Berry L, Parasuraman A. The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 1993; 21: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Santos J, Boote J. A theoretical exploration and model of consumer expectations, post‐purchase affective states and affective behaviour. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 2003; 3: 142–156. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anderson C, Blenkinsopp A, Armstrong M. Feedback from community pharmacy users on the contribution of community pharmacy to improving the public’s health: a systematic review of the peer reviewed and non‐peer reviewed literature 1990–2002. Health Expectations, 2004; 7: 191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hassell K, Noyce P, Rogers A, Harris J, Wilkinson J. Advice provided in British community pharmacies: what people want and what they get. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 1998; 3: 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ojasalo J. Managing customer expectations in professional services. Managing Service Quality, 2001; 11: 200–212. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Renberg T, Kettis Lindblad Å, Tully MP. Exploring subjective outcomes perceived by patients receiving a pharmaceutical care service. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 2006; 2: 212–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McAuley JW, Miller MA, Klatte E, Shneker BF. Patients with epilepsy’s perception on community pharmacist’s current and potential role in their care. Epilepsy and Behavior, 2009; 14: 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guirguis LM, Chewning BA. Role theory: literature review and implications for patient‐pharmacist interactions. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 2005; 1: 483–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Biddle BJ. Recent developments in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 1986; 12: 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Solomon MR, Surprenant C, Czepiel JA, Gutman EG. A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: the service encounter. Journal of Marketing, 1985; 49: 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mackowiak JI, Manasse HR Jr. Expectation vs demand for pharmacy services. Journal of Pharmaceutical Marketing and Management, 1988; 2: 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hirsch JD, Gagnon JP, Camp R. Value of pharmacy services: perceptions of consumers, physicians, and third party prescription plan administrators. American Pharmacy, 1990; 30: 20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tinelli M, Ryan M, Bond C. Patients’ preferences for an increased pharmacist role in the management of drug therapy. The International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 2009; 17: 275–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Porteous T, Ryan M, Bond CM, Hannaford P. Preferences for self‐care or professional advice for minor illness: a discrete choice experiment. British Journal of General Practice, 2006; 56: 911–917. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hedvall M‐B, Paltschik M. Developing pharmacy services: a customer‐driven interaction and counselling approach. Services Industries Journal, 1991; 11: 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brown SR. Political Subjectivity. New Haven and London: Yale University press, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stainton Rogers R. Q methodology In: Smith JA, Harré R, van Langenhove L. (eds) Rethinking Methods in Psychology. London: Sage Publications, 1995: 178–192 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stephenson W. The Study of Behaviour: Q‐Technique and Its Methodology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 41. McKeown B, Thomas D. Q Methodology. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stenner PHD, Cooper D, Skevington SM. Putting the Q into quality of life; the identification of subjective constructions of health‐related quality of life using Q methodology. Social Science and Medicine, 2003; 57: 2161–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Morecroft C, Cantrill J, Tully MP. Individual patient’s preferences for hypertension management: a Q‐methodological approach. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 61: 354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Risdon A, Eccleston C, Crombez G, McCracken L. How can we learn to live with pain? A Q‐methodological analysis of the diverse understandings of acceptance of chronic pain. Social Science and Medicine, 2003; 56: 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Combes H, Hardy G, Buchan L. Using Q‐Methodology to Involve People with Intellectual Disability in Evaluating Person‐Centred Planning. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 2004; 17: 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- 46. van Exel NJA, de Graaf G, Brouwer WBF. ‘Everyone dies, so you might as well have fun!’ Attitudes of Dutch youths about their health lifestyle. Social Science and Medicine, 2006; 63: 2628–2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barbosa JC, Willoughby P, Rosenberg CA, Mrtek RG. Statistical methodology VII: Q‐methodology, a structural analytic approach to medical subjectivity. Academic Emergency Medicine, 1998; 5: 1032–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cross RM. Exploring attitudes: the case for Q methodology. Health Education Research, 2005; 20: 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mrtek RG, Tafesse E, Wigger U. Q‐methodology and subjective research. Journal of Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 1996; 13: 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Burt C, Stephenson W. Alternative views on correlations between persons. Psychometrika, 1939; 4: 269–281. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stephenson W. Technique of factor analysis. Nature, 1935; 136: 297. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Morf ME, Miller CM, Syrotuik JM. A comparison of cluster analysis and Q‐factor analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1976; 32: 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Donner JC. Using Q‐sorts in participatory processes: an introduction to the methodology Social Analysis: Selected Tools and Techniques. Washingthon DC: The World Bank, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hilden AH. Q‐sort correlation: stability and random choice of statements. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 1958; 22: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Westerlund LT, Björk HT. Pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies: practice and research in Sweden. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 2006; 40: 1162–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Renberg T. Patient Perspectives on Community Pharmacy Services [Doctoral dissertation]. Uppsala: Uppsala University, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schmolck P, Atkinson J. PQMethod 2.11. ed; 2002. (http://www.lrz.de/~schmolck/qmethod/index.htm) [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kaiser HF. The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 1958; 23: 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Austin Z, Gregory PA, Martin JC. Characterizing the professional relationships of community pharmacists. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 2006; 2: 533–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hibbert D, Bissell P, Ward PR. Consumerism and professional work in the community pharmacy. Sociology of Health and Illness, 2002; 24: 46–65. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nordgren L. The performativity of the service management discourse‐‘Value creating customers’ in health care. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 2008; 22: 510–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Abu‐Omar SM, Weiss MC, Hassell K. Pharmacists and their customers: a personal or anonymous service? The International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 2000; 8: 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Traulsen JM, Almarsdóttir AB, Björnsdóttir I. The lay user perspective on the quality of pharmaceuticals, drug therapy and pharmacy services: results of focus group discussions. Pharmacy World and Science, 2002; 24: 196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Statistics Sweden : Befolkningens utbildning 2008 [Educational attainment of the population 2008] In: Wadman M. (ed.) Statistiska Meddelanden, Utbildning Och Forskning. Stockholm: Statistiska centralbyrån, 2009: 51. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schommer JC, Sullivan DL, Haugtvedt CL. Patients’ role orientation for pharmacist consultation. Journal of Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 1995; 12: 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE‐AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 1999; 89: 1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. The complete factor arrays, including results for statistical testing of the theoretical model.

Data S2. The literature list that informed the Q sample generation.

Data S3. The full list of statements (The Q sample).

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item