Abstract

Background Public reports about health‐care quality have not been effectively used by consumers thus far. A possible explanation is inadequate presentation of the information.

Objective To assess which presentation features contribute to consumers’ correct interpretation and effective use of comparative health‐care quality information and to examine the influence of consumer characteristics.

Design Fictitious Consumer Quality Index (CQI) data on home care quality were used to construct experimental presentation formats of comparative information. These formats were selected using conjoint analysis methodology. We used multilevel regression analysis to investigate the effects of presenting bar charts and star ratings, ordering of the data, type of stars, number of stars and inclusion of a global rating.

Setting and participants Data were collected during 2 weeks of online questioning of 438 members of an online access panel.

Results Both presentation features and consumer characteristics (age and education) significantly affected consumers’ responses. Formats using combinations of bar charts and stars, three stars, an alphabetical ordering of providers and no inclusion of a global rating supported consumers. The effects of the presentation features differed across the outcome variables.

Conclusions Comparative information on the quality of home care is complex for consumers. Although our findings derive from an experimental situation, they provide several suggestions for optimizing the information on the Internet. More research is needed to further unravel the effects of presentation formats on consumer decision making in health care.

Keywords: conjoint analysis, consumer choice, presentation, public reporting

Introduction

Following other countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, consumer choice has become a critical element of current health‐care reform in the Netherlands. 1 Enhanced consumer choice should contribute to a more demand‐driven health‐care system. In theory, individual responsibility and informed decision making could enforce an important role for health‐care consumers on the health‐care market. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Important conditions for systems based on managed competition are that consumers are provided with accurate comparative information on health‐care performance and that consumers effectively use this information in their decisions. 5 , 6 , 7

Several efforts have been made to assemble and present comparative health‐care information. In addition, an increasing number of performance measurements have become standardized concerning used questionnaires and data collection methods. A good example is the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) in the United States, 8 based on consumers’ own quality assessments. In the Netherlands, Consumer Quality Index (CQ‐index or CQI) instruments have been developed to measure and present consumer experiences in health care. 9 , 10 These instruments are partly based on American CAHPS questionnaires and partly on Dutch QUOTE instruments (QUality Of care Through the patient’s Eyes). 11 Like CAHPS and QUOTE, CQI instruments assess patients’ experiences, rather than their satisfaction. CQI information is presented on the Internet as comparative information to facilitate and stimulate consumer choice in health care. The use of the information should contribute to a more demand‐driven health‐care market and ultimately improve the health‐care system’s efficiency and quality. 12 , 13 Besides consumers, health‐care providers are encouraged to use CQI information in quality improvement initiatives.

The dissemination of consumer experience information and other health‐care quality information has, however, had little impact on consumers’ active use of it so far. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 Despite some findings that consumers have positive attitudes towards and interest in it, 18 , 19 , 20 there is only marginal evidence that consumers actually want to use the information. 3 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 Some research findings suggest that new or unsatisfied patients are interested. 15 , 29 , 30 The inability, unwillingness or disinterest of a great part of the public could result from inadequacies in the presentation of the information. 4 , 5 , 14 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35

As opposed to the rapid standardization of quality measurements in health care, there is no uniformity regarding the presentation of the information. 36 , 37 Star ratings are a common visual display of provider performance information in different countries, but other symbols have been applied as well. Symbols such as stars are sometimes based on provider performance relative to overall performance across providers (relative scores), but stars based on absolute provider performance are also frequently used. Besides the use of symbols, quality information is often presented by horizontal bar graphs using absolute frequencies or percentages of consumers’ responses to questions, with longer bars usually meaning better performance. 38

From research on consumer decision making in other sectors, we know that the way information is presented strongly influences consumers’ responses. Effects of presentation formats have been found among a wide range of consumer markets, such as packaged supermarket products, 39 , 40 , 41 electronics, 42 , 43 and restaurants. 44 For example, presenting verbal or numerical data induces different types of information processing. 43 , 45 , 46 Only a few studies examined the effects of different presentation approaches of comparative health‐care information and comparable effects on consumers’ responses were found: providing visual cues in the form of stars and ordering by performance facilitated consumers’ comprehension and use of information. 47 , 48 In addition, information about diseases and symptoms presented as frequencies or as probabilities provoke distinct responses. 49 , 50 Previous studies have also shown that presentation approaches can have differential effects in different subgroups of consumers, for example among high‐ and low‐numerate individuals. 35 , 51 If certain demographic groups have more difficulty using comparative information than others, this might have important consequences for the effectiveness of health‐care reforms.

In short, the notion that presentation approaches of health‐care information are important has steadily gained ground. 52 , 53 Systematic controlled experiments using different presentation formats have, however, been infrequent in this field, and, with some exceptions, 29 studies have not elaborated on information based on consumer experience. As a result, it remains unclear how existing features of presentation approaches, such as the type and number of stars, influence consumers’ comprehension and use of this kind of information. Therefore, it is important to pay more attention to the design features of comparative health‐care information and to examine the effects of consumer characteristics such as age, sex and education to assess how the information is used by different consumer groups.

In this study, we investigated which presentation features contribute to a ‘correct interpretation’ and ‘effective use’ of Dutch CQI information on home care. More specifically, we looked at the interpretation and use of information concerning provider performance on the quality aspect good contact with clients. This quality aspect is an aspect that is typically considered important by patients in the evaluation of health care, and therefore a standard part of CQI questionnaires and other consumer experience instruments. Someone who is searching for a home care provider can view on the government‐sponsored Internet site KiesBeter (‘choose better’) how clients of different home care providers have experienced the contact with the home care nurses. The question is whether some presentation approaches might help health consumers (people needing home care, or their relatives) to more correctly apply this kind of information.

We consider correct interpretation as the ability to derive correct conclusions about who performs well and who does not. By effective use, we mean the ability to choose the best‐performing provider. Correct interpretation is often considered a key ability to use information properly, and the effective use measure particularly relates to actual decision behaviour. 47 These two concepts and their definitions, in particular the effective use measure, are based on policy assumptions that underlie the current Dutch health‐care system and that of other Western countries. The effective use concept presumes that choosing the best provider is the ‘best choice’. The idea is that health‐care providers will compete for consumers’ interests and arrange health‐care accordingly and that therefore consumers will ultimately receive better quality of care if they more often choose best‐performing providers. 12 , 13

We investigated the effects of several presentation features, namely presenting bar charts and star ratings, ordering of the data, type of stars, number of stars and inclusion of a rating of overall performance. All these presentation features are actually used on the Internet to present CQI information in the Netherlands and health‐care quality information in other countries. 38 The inclusion of an overall rating was of interest because presenting different types of information at the same time can lead to conflicting information. For example, a health‐care provider can have a good overall performance according to respondents of a patient survey, but a relatively bad performance on a particular aspect such as the communication measure.

Because presentation formats of comparative health‐care information on the Internet consist of combinations of presentation features, we also looked at several interaction effects. It could be, for example, that a certain combination of features, such as five stars reflecting absolute provider performance, particularly supports consumers. Besides the effects of presentation features, the influence of respondents’ age, education and sex was examined. As we were interested in presentation of comparative health‐care information for the general population, interactions between presentation features and respondent characteristics were not tested.

Our research question was ‘Which presentation features contribute to consumers’ correct interpretation and effective use of comparative information on the quality of health care?’

Methods

Study design

Using the conjoint analysis methodology, 54 we tested the effects of five presentation features: (i) a combination of bar charts and star ratings vs. only star ratings (display); (ii) an alphabetical ordering of providers vs. a rank ordering of performances (ordering); (iii) stars based on absolute performance vs. stars based on relative performance (type of stars); (iv) three stars vs. five stars (number of stars); and (v) inclusion of an overall rating of health‐care providers or not (overall rating). We chose these variables based on previous research 47 , 48 and the content of the official Dutch government‐sponsored website presenting comparative health‐care performance information (http://www.kiesBeter.nl). 38 All tested features and their levels are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Presentation features and their levels

| Feature | Level | Content | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Display | 1 | Combination bar chart and stars | Bar charts with percentages of consumers’ responses presented in combination with star ratings reflecting provider performance |

| 2 | Bar chart only | Bar charts with percentages of consumers’ responses | |

| 3 | Stars only | Star ratings reflecting provider performance | |

| Ordering | 1 | Ordering by performance | Rank order from high‐performing to low‐performing provider |

| 2 | Ordering by alphabet | Ordering by alphabet (A–E and V–Z) | |

| Type of stars1 | 1 | Relative stars | Star ratings based on mean performance of the particular provider, relative to overall mean performance across all providers |

| 2 | Absolute stars | Star ratings based on absolute mean performance of the particular provider | |

| Number of stars1 | 1 | Three stars | *** |

| 2 | Five stars | ***** | |

| Overall rating2 | 1 | Inclusion overall rating | Additional overall rating of the provider (0–10 response scale), independent of the performance on ‘good contact with clients’ |

| 2 | No inclusion overall rating | No additional overall rating of the provider |

1Not relevant for the presentation formats with bar chart only.

2The overall rating of the health‐care provider is a rating typically given by respondents in a CQI survey on a scale from 0 to 10. It should not be confused with ratings that are summary ratings across a number of different quality indicators.

The combination of all features and levels resulted in a total of 32 experimental formats. We reduced this number to a manageable level by drawing a sample: we constructed a fractional factorial design (Orthoplan in SPSS 14.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) of eight formats, which contained an orthogonal subset of the 32 formats. In addition to this subset, all four formats with the level bar chart only and three formats needed to assess the interaction effects were added to the design. This resulted in a total of fifteen experimental formats to be tested. We focused on both main effects and the following three interaction effects: (i) an interaction between display and ordering; (ii) an interaction between display and overall rating; and (iii) an interaction between type of stars and number of stars.

Respondents filled out an online questionnaire at home. They viewed four randomly chosen formats (shown as records at the top of their computer screen) out of the fifteen formats. Subsequently, they were asked to answer questions about the information in these formats.

Materials

We used fictitious but realistic CQI data to construct the experimental formats of comparative information. Each format consisted of a comparison of five home care providers, which were named A, B, C, D and E in one half of the formats and V, W, X, Y and Z in the other half of the formats to control for potential habituation effects. We presented provider performance on one specific quality aspect of the CQI Home Care instrument, namely good contact with clients (provider–client interaction). This quality aspect is commonly used as part of information based on consumer experience and is composed of questionnaire items about the interaction between clients and the nurses that provide health care at clients’ homes. For example, it informs about the home care nurses’ respectful treatment, their willingness to talk with the client and whether they listen carefully to the client. The answering categories were the following: ‘never’, ‘sometimes’, ‘usually’, and ‘always’, with ‘never’ as most negative experience and ‘always’ as most positive experience. The information was designed according to the style of the Dutch website http://www.kiesBeter.nl, which mainly consists of different shades of the colour blue. For example, the bar graphs are made up of different shades, and the more darker the shade, the more negative patients’ experiences. Examples of three experimental formats are shown in 1, 2, 3.

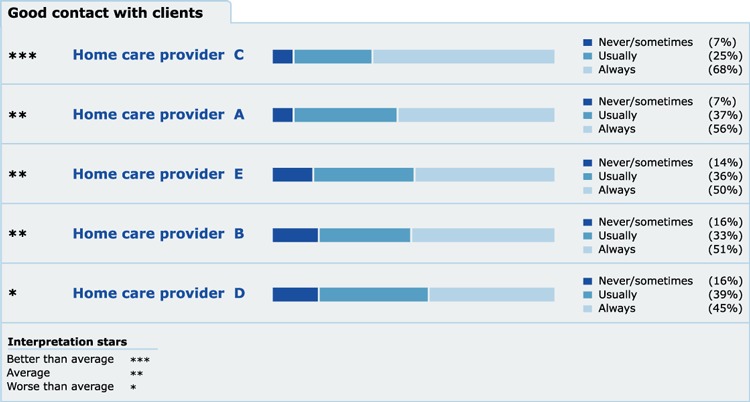

Figure 1.

Example of experimental format: a combination of bar chart and star ratings, a rank ordering of providers, stars based on relative performance, three stars, and no inclusion of an overall rating.

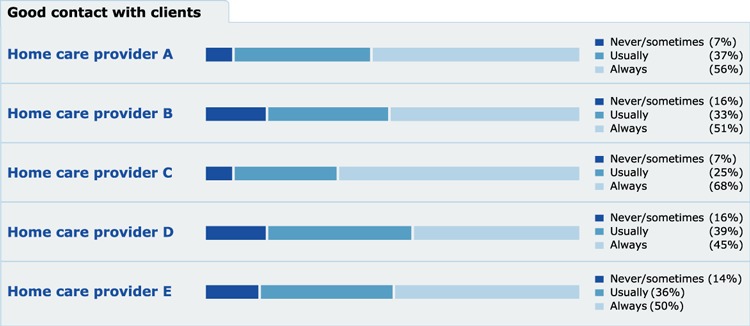

Figure 2.

Example of experimental format: only star ratings, a rank ordering of providers, stars based on relative performance, five stars, and an inclusion of an overall rating.

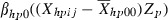

Figure 3.

Example of experimental format: only bar chart, an alphabetical ordering of providers, and no inclusion of an overall rating.

Variables

We asked respondents to imagine that they were choosing a home care provider for themselves or for someone close to them. Below each presented format, questions on consumers’general comprehension, correct interpretation and effective use were formulated. The questions on general comprehension were used to assess how the information was generally comprehended and referred to what was exactly stated in the presented information. We chose to include these items to be able to compare the amount of mistakes respondents made with the amounts reported in previous studies. For example, we asked ‘For which home care provider do clients most often state that there was always good contact with them?’ and ‘According to clients, which home care provider performs satisfactory concerning contact with clients?’ We did not assess the influence of presentation features on these variables, because the nature of the comprehension items (which refer to the actual content of information and thus differs across formats) does not allow to test the effects in our design.

We then had respondents answer a series of questions on correct interpretation and effective use of the presented information, which were used to test the effects of the presentation features. The questions on correct interpretation were intended to assess consumers’ abstract ability to identify good‐ and bad‐performing providers and were as follows: ‘In your opinion, which home care provider has the best contact with clients?’ and ‘In your opinion, which home care provider has the worst contact with clients?’. To assess the effective use of information, we asked respondents which home care provider they would choose, given a situation in which they would need home care: ‘Which home care provider would you choose?’. A choice for the best‐performing provider on the quality aspect ‘good contact with clients’ was considered an ‘effective’ choice (effective use).

All data were unambiguous concerning performance on good contact with clients, with one provider having the highest score. The dichotomous score on each item indicated whether the question was correctly (1) or incorrectly (0) answered. Concerning the effective use of the information, this score indicated whether the best‐performing provider was chosen (1) or not (0). After presenting the four presentation formats, we posed questions on several demographic characteristics (age, education, sex, health status, ethnicity, language spoken at home), current health‐care information seeking, Internet use and experience with home care.

Sample

Participants between 18 and 85 years were drawn from a Dutch online access panel. New panel members were approached, until each format was rated by approximately 100 respondents. Quota sampling was used to ensure even distributions of age, sex and educational level across the different presentation formats, and these distributions corresponded to the distributions in the Dutch population. In the end, a sample of 2052 consumers was approached for participation.

Analyses

First, we conducted descriptive analyses to assess how the information was generally comprehended, interpreted and used. Second, multilevel logistic regression analyses were used to assess the effects of the presentation features and the consumer characteristics age, education, and sex on correct interpretation and effective use. Multilevel analyses take into account the hierarchical structure of the data; in our repeated measures design, the responses are not independent from each other but nested within consumers. For more detail on the multilevel analyses, we refer to the appendix.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 438 (21%) of 2052 persons completed the questionnaire. A total of 165 (8%) subjects started the questionnaire, but did not complete it. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the study sample of 438 consumers. The majority of the respondents were aged between 35 and 54, with almost 17 per cent rating their general health as fair or poor. Hundred and thirty (30%) of the respondents stated that they had searched for information about health‐care providers before. The most frequently cited information sources were the Internet (54%), family and friends (25%), and doctors (22%). Concerning the use of home care, 106 (24%) respondents indicated that they had made use of home care in the past, and 245 (56%) consumers stated that their family or friends had made use of home care in the past.

Table 2.

Participants’ characteristics

| Variable | Respondents | Non‐respondents | Non‐completers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–34 | 77 (17.6%) | 392 (27.0%) | 26 (15.8%) |

| 35–54 | 230 (52.5%) | 869 (60.0%) | 85 (51.5%) |

| 55 or older | 131 (29.9%) | 188 (13.0%) | 54 (32.7%) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 211 (48.2%) | 876 (60.5%) | 80 (48.5%) |

| Male | 227 (51.8%) | 573 (39.5%) | 85 (51.5%) |

| Educational level | |||

| Low | 154 (35.2%) | 680 (46.9%) | 81 (49.1%) |

| Middle | 172 (39.3%) | 407 (28.1%) | 47 (28.5%) |

| High | 112 (25.6%) | 362 (25.0%) | 37 (22.4%) |

| Self‐rated overall health status | |||

| Excellent | 36 (8.3%) | ||

| Very good | 99 (22.5%) | ||

| Good | 230 (52.5%) | ||

| Fair | 58 (13.3%) | ||

| Poor | 15 (3.4%) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non‐Dutch | 24 (5.5%) | ||

| Dutch | 414 (94.5%) | ||

| Language spoken at home | |||

| Dutch | 413 (94.3%) | ||

| Dutch dialect | 16 (3.7%) | ||

| Non‐Dutch | 9 (2.0%) | ||

| Search for information health‐care providers | |||

| Searched for all information | 69 (15.8%) | ||

| Searched for some information | 61 (14.0%) | ||

| Did not search for information | 307 (70.2%) | ||

| Use of Internet | |||

| Daily use | 408 (93.1%) | ||

| Several times per week | 28 (6.3%) | ||

| Once per week | 3 (0.6%) | ||

| Visit of http://www.kiesBeter.nl | |||

| Yes | 71 (34.1%) | ||

| No | 122 (58.6%) | ||

| Don’t know | 15 (7.2%) | ||

| Use of home care | |||

| Made use of domestic care | 44 (10.0%) | ||

| Made use of nursing care | 34 (7.9%) | ||

| Made use of both domestic and nursing care | 28 (6.3%) | ||

| No use of home care | 328 (74.8%) | ||

Age, education and sex of the non‐respondents and persons who stopped filling out the questionnaire (non‐completers) are also displayed in Table 2. The mean age of respondents (46.9 years) differed significantly from the mean age of non‐respondents (41.0 years; F = 80.31; P <0.001), but not from the mean age of non‐completers (47.8 years; F = 0.47; P = 0.49). Non‐respondents were more often women than respondents (χ2 = 20.78; P < 0.001). Again, respondents and non‐completers did not differ from each other (χ2 = 0.001; P = 0.51). Concerning education, non‐respondents and non‐completers were more often lower educated and less often in the middle category of educational level than respondents (χ2 = 25.78; P < 0.001).

Incorrect responses

Table 3 shows the percentages of correct responses to all questions in the study. As each participant responded to four formats, we analysed 1,752 (4 * 438) cases. The percentage incorrect responses varied from 3 to 52% across the items, with an average of 23%. Twelve percent of the respondents did not choose the best‐performing home care provider. When examining the incorrect responses per individual, the percentage incorrect responses varied from 4 to 94%, with an average of 27% mistakes per respondent.

Table 3.

Correct responses to the items; N = 4 × 438 = 1752

| Dependent variable | Item | Correct answer (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehension 1 | At which home care provider do clients most often state that there was always good contact with them? | 88.7 |

| Comprehension 2 | At which home care provider do clients least often state that there was usually good contact with them? | 50.6 |

| Comprehension 3 | According to clients, which home care provider performs more than satisfactory concerning contact with clients? | 48.4 |

| Comprehension 4 | According to clients, which home care provider performs satisfactory concerning contact with clients? | 59.3 |

| Comprehension 5 | According to clients, which home care provider performs average concerning contact wtih clients? | 68.5 |

| Comprehension 6 | According to clients, which home care provider performs worse than average concerning contact with clients? | 84.1 |

| Comprehension 7 | According to clients, which home care provider performs very well concerning contact with clients? | 96.9 |

| Comprehension 8 | According to clients, which home care provider performs unsatisfactory concerning contact with clients? | 80.3 |

| Comprehension 9 | According to clients, which home care provider performs better than average concerning contact with clients? | 88.0 |

| Comprehension 10 | According to clients, which home care provider performs worse than average concerning contact with clients? | 80.7 |

| Interpretation 1: Best performance | In your opinion, which home care provider has the best contact with clients? | 92.0 |

| Interpretation 2: Worst performance | In your opinion, which home care provider has the worst contact with clients? | 73.5 |

| Effective use (Choice) | Which home care provider would you choose? | 88.4 |

Presentation features effects

The results of the multilevel regression analyses are shown in Table 4. Some presentation features significantly affected consumers’ responses. Consumers’ indication of the worst provider (correct interpretation) was positively influenced by presenting a combination of bar chart and star ratings, compared to star ratings only. Including an overall rating for the home care provider had a negative influence on respondents’ indication of the worst‐performing provider. The indication of the best provider (correct interpretation) was not affected by any of the presentation features.

Table 4.

Results of multilevel analyses; regression coefficients with standard errors added in parentheses

| Interpretation 1 (best provider) N = 1752 | Interpretation 2 (worst provider) N = 1752 | Effective use (choice) N = 1752 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.78 (0.13)* | 1.29 (0.09)* | 2.32 (0.11)* |

| β Age 35–541 | −0.48 (0.41) | −0.25 (0.24) | −0.85 (0.38)* |

| β Age > 551 | −1.17 (0.47)* | −0.66 (0.28)* | −1.33 (0.43)* |

| β Female1 | 0.30 (0.29) | 0.09 (0.18) | 0.28 (0.25) |

| β Average education1 | 0.52 (0.27) | 0.37 (0.18)* | 0.31 (0.24) |

| β High education1 | 0.22 (0.37) | 0.44 (0.23) | 0.34 (0.34) |

| β Combination bar chart and stars1 | 0.08 (0.21) | 0.43 (0.15)* | 0.03 (0.19) |

| β Ordering by alphabet1 | 0.23 (0.21) | 0.15 (0.13) | 0.51 (0.19)* |

| β Absolute stars1 | −0.02 (0.27) | −0.16 (0.18) | 0.26 (0.23) |

| β Three stars1 | 0.13 (0.34) | 0.23 (0.23) | 0.77 (0.31)* |

| β No inclusion overall rating1 | −0.32 (0.21) | 1.81 (0.14)* | −0.26 (0.18) |

| β Combination bar chart and stars × Ordering by alphabet | −0.60 (0.54) | 0.35 (0.39) | −0.63 (0.46) |

| β Combination bar chart and stars × No inclusion overall rating | −0.26 (0.47) | −0.25 (0.30) | 0.37 (0.41) |

| β Absolute stars × three stars | 0.25 (0.53) | 0.44 (0.32) | 0.31 (0.48) |

1Reference group age = age 18–34 years; reference group sex = men; reference group education = low education; reference group of display = stars only; reference group ordering = rank ordering by performance; reference group type of stars = relative stars; reference group number of stars = five stars; reference group overall rating = inclusion overall rating; *P < 0.05.

Two presentation features were related to consumers’effective use of the information. First, when ordering by alphabet respondents more often chose the best‐performing provider, compared to an ordering by performance. Second, the number of stars affected consumers’ choice for a home care provider, with three stars being more facilitating than five stars.

For the type of stars and the included interaction terms, no effects on any of the outcome variables were found.

Consumer characteristics effects

In general, older people and less‐educated people had more difficulty processing the information than younger people and higher‐educated people. Age was negatively associated with both consumers’correct interpretation (indicating the best and worst provider) and their effective use. Consumers’ educational level was positively related to the indication of the worst provider (correct interpretation). Education did not relate to either of the other two outcomes. Consumers’ sex was not associated with the outcome variables.

Discussion

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to assess the effects of several presentation features of comparative health‐care information on consumers’‘correct interpretation’ and ‘effective use’. These two concepts are considered important in the policy assumptions about consumer choice. We used Consumer Quality Index information about quality of home care as an example and found that correct interpretation and effective use were partly determined by presentation features of the information. The effects of presentation features differed across the different outcomes. A combination of bar charts and star ratings and no inclusion of an overall rating facilitated consumers’ correct interpretation. Ordering providers by alphabet and using three instead of five stars contributed to consumers’ effective use. Our study has shown that presentation features are important to pay attention to in the context of publishing performance information to consumers. Although our findings derive from an experimental situation, they provide important suggestions for the use of information by consumers.

Discussion of findings

In line with previous studies, our findings show that comparative health‐care information is complex: consumers incorrectly answered a great part of the questions. The average percentage of incorrect answers was 27% per individual. Other studies reported similar percentages. 47 , 55 Particularly older and less‐educated consumers had difficulty interpreting and effectively using the comparative information. Real information on the Internet is far more complex than the limited amount of information presented in our experiment. As level of education and age were seen as proxy for consumers’ ability to process comparative health‐care information, the findings suggest that people from the more disadvantaged groups might not take as much advantage of the information as other consumer groups. An important issue is whether the questions in this study are perhaps too complex for consumers and whether this might influence their interpretation and use of the material. Such task effects have been found in previous research. 56 All in all, the findings suggest that more attention is needed for the complexity of comparative health‐care information and consumers’ abilities to process the information.

The finding that stars combined with bar charts improved consumers’ correct interpretation compared to stars only is new: previous studies found no significant differences. 47 , 48 In our study, the effect was only found when consumers had to indicate the worst‐performing provider, whereas previous studies did not examine this specific capacity of consumers. Notably, an alphabetical ordering of providers facilitated consumers’ effective use. This effect was unexpected and contradictory to previous findings in the United States, in which positive effects of ordering health plans by performance on effective use of information were found. 47 , 48 It could be that American citizens are more accustomed to rankings because of a longer tradition in market‐based competition and therefore more inclined to identify the most excellent performance. However, American websites have thus far also used alphabetical ordering of providers to present comparative information. So the question remains which previous experiences may have ‘primed’ consumers to process information in a particular way. At the current stage, we can only speculate about this somewhat counterintuitive effect. Clearly, more research is needed to further unravel the effects of ordering performance data.

Interestingly, the effects of presentation features differed for the outcomes of correct interpretation and effective use of the information. Combining bar charts and star ratings affected consumers’ correct interpretation when they had to indicate the worst‐performing provider, but not their effective use of the information. In contrast, the number of stars and way of ordering the information influenced consumers’ effective use of the information, but were not related to a correct interpretation. Perhaps different reasoning processes are used as a result of asking different questions. Unfortunately, the nature of our design does not allow for investigating consumers’ information processing and decision strategies. It would be interesting for future studies to investigate these processes, as well as consumers’ awareness of the impact of formats.

Suggestions for presenting patient experience information about home care are to use formats using a combination of bar chart and stars, an alphabetical ordering of health‐care providers, and three stars when supporting consumers in correct interpretation and effective use. Concerning the use of an overall rating, we cannot make clear recommendations. Our finding that people less often correctly indicate the worst‐performing provider when an overall rating is included can probably be attributed to the specific context. That is, the provider who performed worst on good contact with clients was not the worst overall (overall rating), which may have been confusing. Consumers might have concentrated on the provider performing worst overall, represented by the overall rating.

The recommendations made should be seen in the light of the policy assumptions about correct interpretation and effective use in the Dutch and other health‐care systems. These assumptions are based on the idea that consumers act as rational people choosing the best‐performing providers. In our experiment, an even more narrow assumption was used, namely that consumers choose the provider that performs best in terms of ‘good contact’. These assumptions are challenged in several ways. For example, it can be questioned to what extent people act as rational consumers. 57 It is the question whether consumers actually want to choose best‐performing health‐care providers or whether they view comparative information for other reasons (for example to check how their own provider performs). It could also be that certain consumers deliberately choose providers that perform less well on ‘good contact’ indicators, to avoid being intruded by health‐care professionals. More psychological research should focus on these kinds of questions. In addition, future research should also assess the policy assumption about the impact of consumer choice behaviour on the quality and efficiency of health care.

In the context of publishing comparative health‐care information on the Internet, we want to underline that presentation features facilitating consumers’ use of the information are not always the approaches that are also methodologically sound. For example, the use of star ratings may suggest substantial quality differences between providers and thus seems only legitimate when these differences are at least statistically significant. When using stars based on absolute scores, provider differences in the number of stars are not necessarily statistically significant. This is difficult to communicate to both consumers and health‐care providers being monitored. But even when differences are statistically significant, the question remains whether these differences are large enough to present to consumers. In practice, even small differences between providers on CQI performance are often significant because of large sample sizes. Consequently, both health‐care policy makers and researchers should carefully consider presentation formats in relation to the provider differences found in profiling studies.

Limitations and further research

The response rate was relatively low (21%), which might have influenced the composition of our sample and therefore biased the results. However, additional batches of questionnaires were sent to specific subgroups of consumers, to ensure sufficient response rates of these subgroups. This largely succeeded. Analysis revealed that respondents were somewhat older, higher educated and more often men than non‐respondents.

Importantly, almost half of the people not completing the questionnaire had a low education, underlining that the information and/or questions were difficult for consumers to understand. Our sample contained hardly any consumers with a non‐Dutch origin. We recognize that interpretation and use of the material might be more difficult for lower‐educated people and people from ethnic minorities than for the persons in our study, for example because of insufficient language skills. Therefore, future research on the use of comparative health‐care information should focus more on non‐Dutch‐speaking populations and lower‐educated people and investigate the influence of consumers’ reading skills and numeracy concerning health information. 58 , 59

Although our study aimed to assess effective presentation approaches for the general population, we acknowledge that format effects may differ across consumer subgroups. In particular, more or less numerate individuals may react differently to certain presentation approaches. We did not include numeracy measures because possible variations were not theoretically motivated and because our efficient conjoint analysis would not allow for additional subgroup estimation procedures because of small cell sizes. Based on our results and the findings of previous studies, we think that future research should explore the effects of presentation approaches for people with lower numeracy and literacy skills. However, following Reyna and colleagues, 60 more theoretical work is first needed to formulate hypotheses about formatting effects in different consumer subgroups. Educational attainment does not automatically translate into higher numeracy and high‐numerate individuals also make systematic errors in processing numbers. In addition to numeracy, future research could also concentrate on differences between people with different types of illnesses. For example, information (and thus presentation) may play another role for people who need urgent care than for people who undergo routine elective surgery or people with long‐term conditions.

Some of our findings do not correspond to results from previous studies. Further research should be performed to investigate which effects can be replicated for different types of comparative health‐care information, other types of quality indicators, different health‐care sectors, different countries, and other outcome variables. As noted by Shah and Hoeffner, 61 differences in format effects may be attributed to the fact that each experiment with presentation formats only includes a selection of interpretation tasks. In future studies, it is also important to provide consumers with information based on multiple‐quality aspects or other types of indicators, because the ultimate task for consumers is to process all the information and base their decision on it.

Sources of funding

This study was funded by the Netherlands organisation for health research and development (ZonMw).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Annemarie van Rijn and Eliane Poort of the Netherlands Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) for their help in developing the formats of health‐care quality information. Also acknowledged are Hidde Moerman and Binne Heida of Blauw Research for their contribution to the data collection and the design of the study.

A multilevel logistic regression model was used to analyse the data. We used MLwiN 2.02, with the PQL, first‐order, estimation procedure with constrained level 1 variance. At the higher level, we have the individual respondents and nested within the respondents the formats they judged. The model is a standard two‐level random intercept multilevel model, with predictor variables at both levels that are centred on the sample means. Not all format features are present in all presented formats. In these cases, the variable Z p ensures that the contribution to the overall regression for this feature is zero.

The model is:

y = outcome (0,1)

i = format 1 …n

j = respondent 1 …N

β 00 = intercept parameter

β = regression coefficients

= fixed part for the format features

= fixed part for the format features

p = format features 1 … p

h = level of feature (p) 1 … h

X hpij = indicator variable for level (h) of feature (p)

0 = not present

1 = present

= percentages of formats that have this feature present

= percentages of formats that have this feature present

Z p = indicator variable that indicates whether the format feature (p) is present in the current format

0 = not present

1 = present

= fixed part for the consumer characteristics

= fixed part for the consumer characteristics

q = consumer characteristics 1 … q

X q0j = measurement of the consumer characteristic q

= average of the measurement q over all respondents

= average of the measurement q over all respondents

μ 0j = between respondents variance

ɛ ij = binomial error variance

References

- 1. Maarse H, Ter Meulen R. Consumer choice in Dutch health insurance after reform. Healthcare Analysis, 2006; 14: 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bernstein AB, Gauthier AK. Choices in health care: what are they and what are they worth? Medical Care Research and Review, 1999; 3 (Suppl 1): 5–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marshall M, Davies H. Public release of information on quality of care: how are health services and the public expected to respond? Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 2001; 6: 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berwick DM, James B, Coye MJ. Connections between quality measurement and improvement. Medical Care, 2003; 41 (1 Suppl): 130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hibbard JH. Engaging health care consumers to improve the quality of care. Medical Care, 2003; 41 (1 Suppl): 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mannion R, Davies HT. Reporting health care performance: learning from the past, prospects for the future. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2002; 8: 215–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shaller D, Sofaer S, Findlay SD, Hibbard JH, Lansky D, Delbanco S. Consumers and quality‐driven health care: a call to action. Health Affairs, 2003; 22: 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hargraves JL, Hays RD, Cleary PD. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) 2.0 adult core Survey. Health Services Research, 2003; 38(6 Pt 1): 1509–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stubbe JH, Brouwer W, Delnoij DM. Patients’ experiences with quality of hospital care: the Consumer Quality Index Cataract Questionnaire. BMC Ophthalmology, 2007; 7: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stubbe JH, Gelsema T, Delnoij DM. The Consumer Quality Index Hip Knee Questionnaire measuring patients’ experiences with quality of care after a total hip or knee arthroplasty. BMC Health Services Research, 2007; 7: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sixma HJ, Kerssens JJ, Campen CV, Peters L. Quality of care from the patients’ perspective: from theoretical concept to a new measuring instrument. Health Expectations, 1998; 1: 82–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ministry of VWS . Vraag aan bod. Tweede Kamer, vergaderjaar 2000–2001, 27 855, nr 2. The Hague, Ministry of VWS, 2001.

- 13. Ministry of VWS . Vernieuwing van het zorgstelsel. Tweede Kamer, vergaderjaar 2000–2001, 27 855, nr. 17. The Hague, Ministry of VWS, 2001.

- 14. Fung CH, Lim YW, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2008; 148: 111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hibbard JH, Jewett JJ. Will quality report cards help consumers? Health Affairs, 1997; 16: 218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chernew M, Scanlon DP. Health plan report cards and insurance choice. Inquiry, 1998; 35: 9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harris KM. How do patients choose physicians? Evidence from a national survey of enrollees in employment‐related health plans Health Services Research, 2003; 38: 711–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hibbard JH, Jewett JJ. What type of quality information do consumers want in a health care report card? Medical Care Research and Review, 1996; 53: 28–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tumlinson A, Bottigheimer H, Mahoney P, Stone EM, Hendricks A. Choosing a health plan: what information will consumers use? Health Affairs, 1997; 16: 229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Trisolini MG, Isenberg KL. Public reporting of patient survival (mortality) data on the dialysis facility compare web site. Dialysis and Transplantation, 2007; 36: 486–499. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Robinson S, Brodie M. Understanding the quality challenge for health consumers: the Kaiser/AHCPR Survey. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement, 1997; 23: 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Booske BC, Sainfort F, Hundt AS. Eliciting consumer preferences for health plans. Health Services Research, 1999; 34: 839–854. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. The public release of performance data: what do we expect to gain? A review of the evidence JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 2000; 283: 1866–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schneider EC, Lieberman T. Publicly disclosed information about the quality of health care: response of the US public. Quality in Health Care, 2001; 10: 96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Magee H, Davis LJ, Coulter A. Public views on healthcare performance indicators and patient choice. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 2003; 96: 338–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. O’Meara J, Kitchener M, Collier E et al. Case study: development of and stakeholder responses to a nursing home consumer information system. American Journal of Medical Quality, 2005; 20: 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abraham JM, Feldman R, Carlin C, Christianson J. The effect of quality information on consumer health plan switching: evidence from the Buyers Health Care Action Group. Journal of Health Economics, 2006; 25: 762–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marshall M, Noble J, Davies H et al. Development of an information source for patients and the public about general practice services: an action research study. Health Expectations, 2006; 9: 265–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schultz J, Thiede Call K, Feldman R, Christianson J. Do employees use report cards to assess health care provider systems? Health Services Research, 2001; 36: 509–530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jin GZ, Sorensen AT. Information and consumer choice: the value of publicized health plan ratings. Journal of Health Economics, 2006; 25: 248–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Veroff DR, Gallagher PM, Wilson V et al. Effective reports for health care quality data: lessons from a CAHPS demonstration in Washington State. International Journal for Quality in Healthcare, 1998; 10: 555–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harris‐Kojetin LD, McCormack LA, Jaël EF, Sangl JA, Garfinkel SA. Creating more effective health plan quality reports for consumers: lessons from a synthesis of qualitative testing. Health Services Research, 2001; 36: 447–476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hibbard JH, Slovic P, Peters E, Finucane ML, Tusler M. Is the informed‐choice policy approach appropriate for Medicare beneficiaries? Health Affairs, 2001; 20: 199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vaiana ME, McGlynn EA. What cognitive science tells us about the design of reports for consumers. Medical Care Research and Review, 2002; 59: 3–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peters E, Hibbard J, Slovic P, Dieckmann N. Numeracy skill and the communication, comprehension, and use of risk‐benefit information. Health Affairs, 2007; 26: 741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Davies HT, Smith PC. Public reporting on quality in the United States and the United Kingdom. Health Affairs, 2003; 22: 134–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Carlisle RT. Internet report cards on quality: what exists and the evidence on impact. The West Virginia Medical Journal, 2007; 103: 17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Damman OC, Van den Hengel YKA, Van Loon AJM, Rademakers J. An international comparison of web‐based reporting about healthcare quality: content analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2010; 12: e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Russo JE, Krieser G, Miyashita S. An effective display of unit price information. Journal of Marketing, 1975; 39: 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bettman JR, Kakkar P. Effects of information presentation format on consumer information acquisition strategies. Journal of Consumer Research, 1977; 3: 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Biehal G, Chakravarti D. Information‐presentation format and learning goals as determinants of consumers’ memory retrieval and choice processes. Journal of Consumer Research, 1982; 8: 431–441. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Painton S, Gentry JW. Another look at the impact of information presentation format. The Journal of Consumer Research, 1985; 12: 240–244. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shen YC, Hue CW. The role of information presentation formats in belief updating. International Journal of Psychology, 2007; 42: 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jarvenpaa SL. The effect of task demands and graphical format on information processing strategies. Management Science, 1989; 35: 285–303. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Russo JE, Dosher BA. Strategies for multiattribute binary choice. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, memory, and cognition, 1983; 9: 676–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lindberg E, Gärling T, Montgomery H. Prediction of preferences for and choices between verbally and numerically described alternatives. Acta Psychologica, 1991; 76: 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hibbard JH, Peters E, Slovic P, Finucane ML, Tusler M. Making health care quality reports easier to use. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement, 2001; 27: 591–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hibbard JH, Slovic P, Peters E, Finucane ML. Strategies for reporting health plan performance information to consumers: evidence from controlled studies. Health Services Research, 2002; 37: 291–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yamagishi K. When a 12.86% mortality is more dangerous than 24.14%: implications for risk communication. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 1997; 11: 495–506. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hoffrage U, Lindsey S, Hertwig R, Gigerenzer G. Medicine. Communicating statistical information. Science, 2000; 290: 2261–2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Greene J, Peters E, Mertz CK, Hibbard JH. Comprehension and use of a consumer‐directed health plan: an experimental study. American Journal of Managed Care, 2008; 14: 369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hibbard JH, Peters E. Supporting informed consumer health care decisions: data presentation approaches that facilitate the use of information in choice. Annual Review of Public Health, 2003; 24: 413–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ancker JS, Kaufman D. Rethinking health numeracy: a multidisciplinary literature review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 2007; 14: 713–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for healthcare. BMJ, 2000; 320: 1530–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Tusler M. It isn’t just about choice: the potential of a public performance report to affect the public image of hospitals. Medical Care Research and Review, 2005; 62: 358–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Payne JW, Bettman JR, Johnson EJ. The Adaptive Decision Maker. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hsee CK, Hastie R. Decision and experience: why don’t we choose what makes us happy? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2006; 10: 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Donelle L, Hoffman‐Goetz L, Arocha JF. Assessing health numeracy among community‐dwelling older adults. Journal of Health Communication, 2007; 12: 651–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ginde AA, Clark S, Goldstein JN, Camargo CA. Demographic disparities in numeracy among emergency department patients: evidence from two multicenter studies. Patient Education and Counseling, 2008; 72: 350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Reyna VF, Nelson WL, Han PK, Dieckmann NF. How numeracy influences risk comprehension and medical decision making. Psychological Bulletin, 2009; 135: 943–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Shah P, Hoeffner J. Review of graph comprehension research: implications for instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 2002; 14: 47–69. [Google Scholar]