Abstract

Background Involving patients in the determination of their care is increasingly important, and health‐care professionals worldwide have recognized a need for clinical outcome measures and interventions that facilitate patient‐centred care delivery in a range of settings.

Aim A mixed‐methods review was conducted, which aimed to identify stroke‐specific patient‐centred outcome measures and patient‐centred interventions.

Search strategy Databases searched included MEDLINE and PsycINFO; search strings were based on MeSH terms and keywords associated with the terms ‘stroke’ and ‘patient‐centred’.

Data extraction and analysis Descriptive statistics were used to report quantitative data; thematic analysis was also performed in the included studies.

Main Results Three patient‐centred outcome measures (Subjective Index of Physical and Social Outcomes, Stroke Impact Scale, Communication Outcome after Stroke scale) and four interventions were identified. Key elements of intervention design included delivery in people’s own homes, involvement of families and tailoring to individual needs and priorities. Thematic analysis enabled description of three broad themes: meaningfulness and relevance, quality, and communication, which informed the development of a definition of patient‐centred care specific to the specialty of stroke.

Conclusions It is important for health‐care professionals to ensure that their practice is relevant to patients and families. The review identified three stroke‐specific patient‐centred outcome measures, key elements of patient‐centred interventions, and informed the development of a definition of patient‐centred care. These review‐derived outputs represent a useful starting point for health‐care professionals, whatever their specialty, who are working to reconcile tensions between priorities of health‐care professionals and those of patients and their families, to ensure delivery of patient‐centred care.

Keywords: care, definition of patient‐centred care, outcome measures, patient involvement, patientcentred, patients and families, stroke

Background

Over recent years, UK government policy has described the need for a health‐care service that is responsive to the needs and priorities of service users and their families. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 In response to this policy imperative, both service providers and users have advocated the design and delivery of patient‐centred services. 5 , 6 As it entered the twenty‐first century, the UK National Health Service (NHS) adopted a patient‐centred approach to the design, development and delivery of health‐care services. 2 Service users have been empowered to contribute at a number of different levels by means of mechanisms such as Local Involvement Networks 7 and Managed Clinical Networks. 8 Interventions designed to promote patient‐centred consultations in primary‐care settings have a positive impact on a range of patient outcomes including health status, knowledge, compliance and satisfaction with care. 9 , 10 However, ensuring delivery of patient‐centred services at the point of care delivery remains problematic for many health‐care professionals (HPs), particularly those working in clinical specialties where more traditional models of care delivery prevail. 8 , 11 Traditional approaches to care delivery, such as medical models, which adopt a paternalistic approach to service design and delivery, 5 , 12 often result in tension between the aims and priorities of HPs and those of patients and families accessing health‐care services. 5 , 8 , 13 Several studies have described divergence evident between priorities and goals of HPs and priorities and goals of patients with stroke and their families. For example, Redfern et al. 14 found that HPs and patients had different priorities with respect to prevention of recurrent stroke, and tensions arose between HPs and patients whose views of the experience of stroke differed. Although stroke services may deliver in terms of successful rehabilitation outcomes, i.e. survival, return home and independence from the activities of daily living, 15 these are most frequently assessed from the perspective of stroke clinicians rather than from the perspective of patients and their families. To further improve stroke service delivery and to improve patients’ and families’ experiences of engagement with stroke services, it is essential that stroke care moves to a patient‐centred model of service delivery in line with demands from policymakers, clinicians and service users. Identified barriers to the instigation of patient‐centred practice and patient‐centred care delivery include lack of an accepted definition of patient‐centred care, 5 , 14 , 16 , 17 lack of understanding of the needs, priorities and goals of patients and their families, 18 , 19 and lack of patient‐centred outcome measures. 5 , 20 A robust definition of patient‐centred care is required, that will provide a benchmark against which stroke HPs can measure their clinical practice. HPs also need to be able to gain an understanding of, or an insight into patients’ concerns, priorities and anticipated outcomes, which may include goals associated with domestic, social or employment outcomes. 21 , 22 , 23 Although there is an extensive range of outcome measures available for use in clinical practice, e.g. National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIH Stroke Scale), 24 Barthel Index (BI), 25 Functional Independence Measure (FIM) 26 and Frenchay Activities Index (FAI), 27 they measure clinical outcomes such as mortality, impairment, disability (activity) and handicap (participation) and are not specific to the specialty of stroke. 16 , 28 As such, these outcome measures reflect generic priorities of HPs, rather than specific needs and concerns of individual patients, following stroke. 21 , 29 Acknowledging these deficits in stroke outcome measurement, a need has been articulated for comprehensive outcome measures, which facilitate HPs’ understanding of priorities and goals of patients with stroke, and how these may change over time. 16 , 20 , 30 Measures are required that will support HPs in the provision and evaluation of stroke rehabilitation services that patients perceive as effective and meaningful. 5 , 29

Barriers to the implementation of patient‐centred stroke care have been described in the stroke literature. 14 , 18 These barriers need to be addressed in order for stroke services to continue to develop in accordance with the patient‐centred model required by policy makers, clinicians and service users. This paper reports the outcomes of a systematic review that was undertaken, as part of a programme of PhD research, to identify stroke‐specific patient‐centred outcome measures and interventions that are sufficiently comprehensive and flexible to support the measurement and delivery of patient‐centred stroke care. However, this focus on identification of patient‐centred outcome measures specific to the specialty of stroke begs the question of whether there is any need for a disease‐specific definition of patient‐centredness or disease‐specific patient‐centred outcome measures. This apparent shift in focus may be interpreted as a return to a more biomedical model in which the disease was seen to define the person. 5 Although there is evidence that patient outcomes are improved by generic approaches to patient‐centred to care delivery, typically, the outcomes measured in such studies were not selected by patients, which gives cause for concern with regard to the meaningfulness and relevance of these outcomes. 5 , 9 Therefore, our aim to focus on stroke‐specific outcomes, identified as important and relevant by people who have direct experience of stroke, reflects a truly patient‐centred approach to the issues of definition and measurement in the delivery of patient‐centred care.

Aim

The review aimed to identify stroke‐specific patient‐centred outcome measures, patient‐centred interventions and family‐centred interventions. A secondary aim was to assess the patient‐centred nature of any measures and interventions identified.

Methods

An inclusive systematic review methodology was adopted that allowed the inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative papers (Table 1). 31 The review comprised five stages: literature search, inclusion/exclusion, screening, quality assessment and data extraction, and data analysis (i.e. quantitative analysis and data synthesis). Because of resource constraints, only ML worked on every stage of the review process. Therefore, mechanisms were put in place to ensure rigour and to ratify the review process, i.e. discussions were held with experienced systematic reviewers at every stage, and an experienced systematic reviewer independently extracted data from a proportion of papers included at Stage 4 and assessed whether they were patient‐centred; any discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved consensually. 32

Table 1.

Narrow inclusion/exclusion criteria (PISO)

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults (18 years+) post‐stroke in any care location, e.g. acute care, rehabilitation, nursing home, own homes Family members/relatives of adults post‐stroke | Diseases/conditions other than stroke General rehabilitation (i.e. not stroke specific) Where the focus is on stroke health professionals and not the patient with stroke or family |

| Interventions | Any intervention that describes its underpinning philosophy as patient‐centred (PC) Any intervention that describes its underpinning philosophy using synonyms of PC such as ‘client‐centred’ | Psychotherapy/counselling Pharmaceutical interventions/treatments (clinical) assessment of family functioning, i.e. where the approach is clinical rather than PC and the intervention is standard procedure, i.e. not personalized |

| Study design | Any – except those in exclusion criteria | Literature review Single case study Discussion/view point paper Guidelines/‘how to’ documents Value/policy statement News item |

| Outcomes | Any outcome that describes itself as patient‐centred Any outcome that describes itself using synonyms of PC | Quality of life measures Patient satisfaction measures Self‐reported health status measures |

The Stage 1 literature search covered the period May 1994–January 2010, dates that reflect the development of patient‐centred health‐care policy and service delivery development. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Key bibliographic databases of medical and health literature, psychology and social sciences, i.e. AMED, ASSIA, BNI, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), ACP Journal Club, DARE, CCTR, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE and PsycINFO, were searched. Search strings were developed based on MeSH terms and keywords associated with the terms ‘stroke’ and ‘patient‐centred’. A Cochrane ‘stroke’ search strategy 33 was used in databases hosted by OVID and amended for use in other databases. 34 For patient‐centred terminology, searches were based on a wide range of synonyms previously identified in a review of patient‐centred dietary outcomes. 35 , 36 A total of 15 complex search strings were developed using key words such as patient?cent?red, patient?perspective, patient?based, person?centred, person?focused, and family?oriented.

In Stage 2 (inclusion/exclusion), titles and abstracts (where available) of all papers retrieved in Stage 1 searches were read and broad inclusion criteria (i.e. ‘stroke’ and ‘patient‐centred’) were applied. Papers that did not meet the broad criteria were excluded. Eligible papers were submitted to Stage 3 (screening) of the process, in which papers were screened using narrow selection criteria defined in terms of study Population, Interventions/measures, Study design and Outcomes (PISO; Table 1). 37 Papers that met these ‘PISO’ criteria were submitted to Stage 4 (i.e. quality assessment and data extraction).

In Stage 4, papers underwent quality assessment and data extraction. As is common in mixed‐method reviews, no overall quality rating score was assigned to individual papers and no papers were excluded on grounds of quality. 31 , 38 A quality assessment checklist and coding sheet 35 were developed to enable assessment of the various papers according to design‐specific criteria. 31 , 37 The results of the quality assessment process are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of outcomes of the quality assessment

| Paper | Generic aspects | Design‐specific aspects |

|---|---|---|

| Burton 18 | Aim of the research: A Design: P Informed consent: yes Ethics approval: yes Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: P Rigour: A | Grounded Theory (used to analyse the data) Concurrent data collection and analysis: A Theoretical sampling: P Core theory grounded in the data: P First‐ and second‐level coding: A Theoretical saturation: No |

| Clark & Rugg 48 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: yes Ethics approval: yes Role of the researcher: yes Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A Rigour: A | Qualitative interviews No design‐specific criteria were described for studies described only in broad terms as ‘qualitative’ and which employed interviews as the data collection method |

| Cup et al. 56 | Aim of the research: A Design: P Informed consent: yes Ethics approval: yes Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: P | Psychometric testing Inclusion criteria: yes Exclusion criteria: yes Sample size calculation: no Bias: A Analyses: A |

| Duncan et al. 20 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: NC Ethics approval: NC Role of the researcher: no Limitations: no Findings discussed in relation to the literature: P Note: brief paper; insufficient detail provided regarding most aspects of study design and conduct. | Qualitative interviews No design‐specific criteria were described for studies described only in broad terms as ‘qualitative’ and which employed interviews as the data collection method |

| Ekstam et al. 50 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: NC Ethics approval: yes Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Prospective longitudinal Inclusion criteria: yes Exclusion criteria: yes |

| Ellis‐Hill et al. 13 | Aim of the research: P Design: A Informed consent: yes Ethics approval: yes Role of the researcher: yes Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Qualitative interviews No design‐specific criteria were described for studies described only in broad terms as ‘qualitative’ and which employed interviews as the data collection method |

| Fox et al. 45 | Aim of the research: A Design: P Informed consent: NC Ethics approval: NC Role of the researcher: yes Limitations: P Findings discussed in relation to the literature: P | Ethnography Describes social group: yes Interviews and observations: A Carried out over an extended period: yes Individual/group behaviour: yes Note: authors did not use the term ethnography; study fits the criteria |

| Glass et al. 41 , 42 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: yes Ethics approval: yes Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: P | RCT Inclusion criteria: yes Exclusion criteria: yes Sample size calculation: yes Randomization sequence: A Concealment of allocation: A Comparability of groups: yes Blinding of outcome assessors: A Attrition: discussed in detail |

| Grant & Davis 44 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: NC Ethics approval: NC Role of the researcher: yes Limitations: no Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Grounded Theory Concurrent data collection and analysis: P Theoretical sampling: P Core theory grounded in data: A First‐ and second‐level coding: P Theoretical saturation: yes |

| Harris & Eng 47 | Aim of the research: A Design: P Informed consent: NC Ethics approval: yes Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Descriptive case study Inclusion criteria: yes Exclusion criteria: yes |

| Jansa et al. 52 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: NC Ethics approval: NC Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Case–control study Inclusion criteria: no Exclusion criteria: no Recruitment and selection of cases: A Bias: P Confounding factors: P |

| Kersten et al. 55 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: yes Ethics approval: yes Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Cross‐sectional survey Inclusion criteria: yes Exclusion criteria: yes Sample size calculation: yes Response rate: A Bias: I Analyses: P |

| Ljungberg et al. 53 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: yes Ethics approval: yes Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Case–control study Inclusion criteria: yes Exclusion criteria: no Recruitment and selection of cases: A Bias: P Confounding factors: A |

| Long et al. 28 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: yes Ethics approval: yes Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: no | Cross‐sectional interview‐based psychometric testing Inclusion criteria: yes Exclusion criteria: yes Sample size calculation: no Bias: A Analyses: A |

| Nordehn et al. 46 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: yes Ethics approval: NC Role of the researcher: yes Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Focus groups Interaction between participants: P |

| Pound et al. 49 | Aim of the research: P Design: P Informed consent: NC Ethics approval: NC Role of the researcher: no Limitations: no Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Qualitative interviews No design‐specific criteria were described for studies described only in broad terms as ‘qualitative’ and which employed interviews as the data collection method |

| Secrest 43 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: yes Ethics approval: yes Role of the researcher: yes Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Phenomenology Underpinning philosophy: A Bracketing (if Husserlian): A Meaning o the experience: A Interpretation of meaning: A Unstructured data collection: A Systematic data analysis: A Transparency: no; Representation: no Essence of the phenomenon: A |

| Studenski et al. 51 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: yes Ethics approval: NC Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: P | Prospective cohort study Inclusion criteria: yes Exclusion criteria: yes |

| Trigg et al. 30 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: NC Ethics approval: NC Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Qualitative interviews No design‐specific criteria were described for studies described only in broad terms as ‘qualitative’ and which employed interviews as the data collection method |

| van Bennekom et al. 54 | Aim of the research: A Design: P Informed consent: NC Ethics approval: NC Role of the researcher: no Limitations: A Findings discussed in relation to the literature: I | Case–control study Inclusion criteria: yes Exclusion criteria: yes Recruitment/selection of cases: Bias: A Confounding factors: A |

| Wressle et al. 11 | Aim of the research: A Design: A Informed consent: NC Ethics approval: NC Role of the researcher: yes Limitations: no Findings discussed in relation to the literature: A | Grounded Theory Concurrent data collection and analysis: A Theoretical sampling: P Core theory grounded in the data: I First‐ and second‐level coding: P Theoretical saturation: yes |

Key to quality assessment codes: A, Adequate; P, Partial; I, Inadequate; NC, not clear/not reported.

A comprehensive data extraction form and coding sheet were developed for use in Stage 4, 32 , 35 which enabled the extraction of data from either quantitative or qualitative papers. Many data items were generic, e.g. number of participants, gender; however, some were specific to quantitative study designs, e.g. details of any outcome measures used. Long’s 16 criteria for generic patient‐centred outcome measures (Box 1) were incorporated into the data extraction form and used as a benchmark against which to judge the patient‐centred nature of outcome measures and interventions identified by the systematic review process. Long’s 16 definition of outcome measures was selected for use in the review as it acknowledges the need for breadth and flexibility in the measurement of patient outcomes and acknowledges that outcomes desired by patients are liable to change over time, that they may either coincide with, or diverge from, those of HPs, and that they may be divergent from outcomes desired by their family members. These criteria have previously been described in the literature as essential elements of patient‐centred outcome measures. 5 , 16 , 21 The data extraction form included four criteria adapted from Long. 16

In Stage 5 (analysis), as no meta‐analysis was possible because of the heterogeneity of data collected within the studies, descriptive statistics were used to report quantitative data. In addition, as an analytical method was required that was sufficiently flexible to permit the integration of both quantitative and qualitative papers, review papers were also subject to a process of data synthesis, i.e. thematic analysis. 31 Because of the heterogeneity of study designs and topics, ML produced synopses of the papers and from these synopses identified findings and themes, which were extracted and compiled in tabular form. To ensure that analysis was substantiated by original data, evidence supporting the findings and themes was also extracted. The themes were then assembled into groups of like themes or categories, which were then synthesized into broad categories or overarching themes from which a theoretical framework describing patient‐centred stroke care could be developed. 39 , 40

| Box 1 Long’s definition of a patient‐centred outcome measure |

| It identifies outcomes that are desired and valued by individuals (patients). |

| It is developed to reflect patient priorities. |

| Measurement is undertaken at appropriate times and points within routine clinical care. |

| The resultant information is used to inform the health‐care professional/patient decision‐making process, service evaluation, audit and planning. |

Results

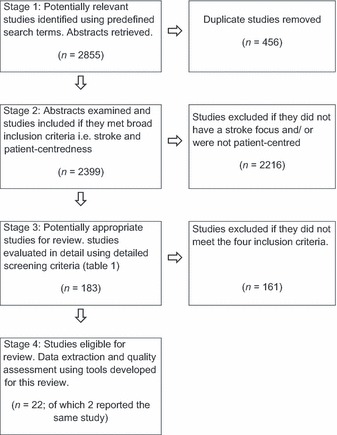

Stage 1 searches retrieved bibliographic records for 2855 papers. The screening and appraisal processes (Stages 2 and 3) resulted in the elimination of 2833 papers (Fig. 1). However, two papers by Glass et al. 41 , 42 reported aspects of development of the same intervention. Therefore it was decided to review the two papers together, i.e. to treat them as one paper. Consequently, 22 papers reporting 21 studies were subjected to Stage 4 quality assessment and data extraction processes.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing inclusion and exclusion of studies.

Results: quantitative analysis

Of the 21 studies, 12 used qualitative methods, i.e. phenomenology, 43 grounded theory, 11 , 18 , 44 ethnography, 45 focus groups, 46 descriptive case study, 47 a generic qualitative methodology; 13 , 20 , 30 , 48 , 49 and nine used quantitative methods, i.e. RCT, 41 , 42 prospective cohort study, 50 , 51 case–control, 52 , 53 , 54 cross‐sectional survey 55 and psychometric testing. 28 , 56

Three of the 21 studies reported development of outcome measures, 20 , 28 , 30 one reported psychometric testing of one of those measures, 55 six sought to evaluate whether stroke care, in a range of settings, was patient‐centred, of these one used qualitative methods, 11 and five used quantitative methods. 47 , 51 , 52 , 54 , 56 Four reported interventions, 41 , 42 , 43 , 50 , 53 and seven were qualitative explorations of the aspects of stroke care. 13 , 18 , 43 , 44 , 46 , 48 , 49

The results of quantitative analysis of the 21 studies, including details of characteristics of study populations, are summarized in Table 3. 35 However, two aspects of the quantitative analysis, study location and inclusion/exclusion of people with aphasia and other stroke‐related communication impairments, are presented in more detail later, as they are particularly pertinent to the topic of this paper.

Table 3.

Evidence table

| Author (year) country | Study aim | Sample | Data collection methods; outcome measures | Details of intervention or outcome measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burton (2000) UK | To describe the lived experience of recovery from the patient’s perspective | Number: 6 Age: 52–81 (range) Gender: 2 (male), 4 (female) Ethnicity: Not stated (NS) Marital status: married: 2, widowed: 2, divorced: 1, single: 1 Employment: employed: 2, not employed: 4 Time: NS; Severity: NS | Data collection: unstructured and semi‐structured interviews, monthly for up to 1 year Measures: Not applicable (N/A) | Not applicable (N/A) | Main findings: Recovery from stroke involved restructuring and adaptation in physical, social and emotional aspects of life. No end point of recovery was described. Social participation was prioritized over physical function |

| Clark & Rugg (2005) UK | To determine the views of stroke survivors and occupational therapists regarding the importance of independent toileting | Number: 13 Age: 75 (mean) Gender: 4 (male), 9 (female) Ethnicity: Caucasian: 13 Marital status: NS Employment: NS Time: 19 days (mean) Severity: NS | Data collection: One‐off semi‐structured interviews Measures: N/A | N/A | Main findings: Independence in toileting was important as it avoided the need for assistance and avoided feelings of decreased self‐esteem The method of toileting was important, not just independent conduct of the activity |

| Cup et al. (2003) Netherlands | To research test–retest reliability and validity of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) in patients with stroke | Number: 26 Age: 68 (mean) Gender: 11 (male), 15 (female) Ethnicity: NS Marital status: NS Employment: NS Time: 2 months: n = 2, 6 months: n = 24 Severity: Ranking score ≤ 2 | Data collection: structured interviews; Measures: COPM, Barthel Index (BI), Frenchay Activities Index (FAI), Stroke Adapted Sickness Impact Profile 30, Euroqol 5D, Rankin | Outcome measure testing Measure: COPM Patient group: community‐dwelling general stroke population Psychometric testing: discriminant validity and test–retest reliability | Test–retest reliability: performance score – Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient 0.89 (P < 0.001) and satisfaction score – 0.88 (P < 0.001) Discriminant validity: confirmed |

| Duncan et al. (2001) USA | To ensure content validity of a new stroke outcome measure: the Stroke Impact Scale | Number: 30 Age: minor stroke: 69.2 (mean), moderate stroke: 71.9 (mean) Gender: 15 (male), 15 (female) Ethnicity: White: 24, Hispanic: 1, African‐American: 5 Marital status: Married: 16 Employment: NS Time: ≤6 months Severity: NIH SS mild (n = 14) 1.9 (SD 1.4); moderate (n = 16) 3.5 (SD 2.73) | Data collection: Series of 3 structured interviews, focus groups; Measures: Orpington Prognostic Scale (OPS), National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), Folstein Mini‐Mental, Geriatric depression Screen, Lawson IADL, MOS‐36 physical function | Outcome measure development Focus: physical function, emotion, memory and thinking, communication, role function (social participation Patient group: general stroke population Assesses: 8 domains: strength, hand function, activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental ADL, mobility, communication, emotion, memory and thinking, participation Items: 64; self‐report Completion time: NS Psychometric testing: test–retest reliability, construct validity Patient‐centred: developed using patient‐derived data | Test–retest reliability: Cronbach α coefficients ranged from 0.83 – 0.90 and met criteria for change over time. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) of the 8 domains were in the range 0.7 – 0.92, except for emotion (0.57) Validity: Domains compared with established measures – correlations were moderate to stroke (0.44–0.84) |

| Ekstam et al. (2007) Sweden | To explore change in function during the first year after stroke for elderly patients participating in rehabilitation at home | Number: 27 Age: 78.8 (mean) Gender: 9 (male), 18 (female) Ethnicity: NS Marital status: NS Employment: NS Time: 1 month (approx) Severity: Scandinavian Stroke Scale: 49 (median) | Data collection: a series of 4 structured interviews over 12 months Measures: Life Satisfaction Scale, Scandinavian Stroke Scale, Timed Up and Go, Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale, Assessment of Motor and Process Skills, Katz Extended Index of ADL, FAI, Occupational Self Assessment | Focus: improving patient satisfaction with life following stroke; includes functioning, life events, environmental barriers Location: patients’ own homes Duration: daily for 29 days (mean), for 1 h (approx) Delivery: one‐to‐one Content: task‐oriented interventions meaningful to patient. Staff: nurse, occupational therapist (OT), physiotherapist plus doctor, social worker, speech and language therapist, psychologist, if required Staff training: NS | Main findings: 4 different patterns identified: 1: moderate change in function (n = 4), 2: minor change (n = 11), 3:minor change despite major life event (n = 7), 4: disrupted change in functioning (n = 5) The group improved significantly in most aspects of functioning, but most participants (n = 20) showed dissatisfaction with life at 12 months post‐stroke |

| Ellis‐Hill et al. (2009) UK | To develop patients’ experiences of the transition from hospital to home | Number: 20 Age: 70 (mean) Gender: NS; Ethnicity: NS Marital status: Married; 10 Employment: NS Time: NS Severity: BI 16.3 (mean) | Data collection: one‐off semi‐structured interviews Measures: BI, Functional Ambulation Category | N/A | Main findings: Participants described recovery in terms of momentum and getting on with life Discharge was successful if momentum was maintained, patients felt supported and were kept informed |

| Fox et al. (2004) USA | To identify the critical elements and outcomes of a residential intervention for families living with aphasia | Number: Family members (FMs):19, People with Aphasia (PwA): 19 Age: range 47–76 Gender: NS Ethnicity: NS Marital status: Married couples: 10 Employment: NS Time: 3 months–10 years Severity: NS | Data collection: telephone interviews and focus groups, one month after the intervention Measures: none | Focus: support for caregivers and PwA Location: residential camp Duration: 2 days Delivery: group sessions Content: communication methods, information, respite, enhancing support networks, establishing new support networks Staff: Group facilitators supported by nurses, and speech and language Therapists Staff training: Group facilitators trained in advanced educational methods and therapeutic group processes | Main findings: Critical intervention elements: Provision of an emotionally and physically safe environment Respite from caregiving Peer learning Participants’ perspective: Renewed sense of hope Improved ability to access social support resources Caregivers improved ability to monitor their own wellbeing Greater acceptance of altered nature of the family Development of new social network |

| Glass et al. (2004) USA | To examine the effects of a family systems intervention designed to influence social support and self‐efficacy | Number: IG: 143, CG: 141 Age: IG: 69 (mean), CG: 70 (mean) Gender: IG: 74 (male), 69 (female), CG: 70 (male), 71 (female) Ethnicity: IG: White: 121, non‐white: 22, IG: White: 127, non‐white: 14, Marital status: IG: widowed: 32, CG: widowed: 48 Employment: NS Time: IG: 22 days (average) CG: 22 days (average) Severity: NS | Data collection: structured interviews at 3 time points up to 6 months post‐stroke Measures: BI, NIH Stroke Severity Index, Boston Aphasia Severity Rating Scale | Psychosocial intervention (PSI) Focus: social integration Location: own home or rehabilitation centre Duration: once a week for 12 weeks, then 3 times per week for 12 weeks Delivery: 90‐min sessions, up to 15 sessions, family plus support network Content: self‐efficacy through stroke education, optimizing social support, maximizing stress reduction, enhanced problem solving, goal setting Staff: clinical psychologist or social worker; Staff training: PSI | Main findings: Functional recovery did not differ between the two groups Adjusted logistic regression demonstrated that the odds of being functionally independent at 6 months were 60% higher in the intervention group; this was not statistically significant |

| Grant & Davis (1997) USA | To explore feelings of self‐loss from the perspective of family carers | Number: patients: 10, spouses/carers: 10 Age: patients: 62 (mean), spouses/carers: 48 (mean) Gender: patients: 4 (male), 6 (female), spouses/carers: 1 (male), 9 (female) Ethnicity: patients: African‐American: 5, White: 5, spouses/carers: African‐American: 5, White: 5 Marital status: 10 x dyads Employment: NS Time: NS; Severity: NS | Data collection: face‐to‐face semi‐structured interviews; telephone interviews 1 week later Measures: N/A | N/A | Main findings: Family caregivers experience four major self‐losses, i.e. loss of familiar self, autonomous self, affiliate self and the knowing self |

| Harris & Eng (2004) Canada | To identify goal priorities in patients with chronic stroke | Number: 19 Age: NS Gender: NS Ethnicity: NS Marital status: NS Employment: NS Time: 6.8 years (mean) Severity: 2.5 (mean) American Heart Association Stroke Outcome Classification (AHASOC) | Data collection: One‐off interviews; Measures: COPM, AHASOC | N/A | Most frequently cited problems: bathing (self‐care) 42%; household maintenance (productivity) 32%; walking outdoors (leisure) 32% Importance of domains: self‐care (8.5), productivity (8.3), leisure (8.7) Patient‐centred approach to assessment revealed that adults with chronic stroke reported issues that could benefit from rehabilitation input |

| Jansa et al. (2004) Slovenia | To introduce a client‐centred approach in an acute stroke setting | Number: 80 Age: 65 (mean) Gender: 52 (male), 28 (female) Ethnicity: NS Marital status: NS Employment: NS Time: 7 days post admission (mean) Severity: NS | Data collection: Assessment at start and end of occupational therapy input; Measures: Extended Barthel Index, COPM | N/A | Frequency of problems: self‐care 97%; productivity 17%; leisure 44% Most frequently cited: self‐care 78%; productivity 10%; leisure 12% Patient‐centred approach to assessment in an acute setting was possible with 36% of patients; other patients could not participate because of impaired cognition, communication, or emotional functioning |

| Kersten et al. (2004) UK | To test the validity of the Subjective Index of Physical and Social Outcome (SIPSO) | Number: 390 Age: 55.7 (median), 21–66 (range) Gender: 222 (male),150 (female) Ethnicity: NS Marital status: NS Employment: Employed: 81, Retired early: 205, Not employed: 79 Time: ≤5 years: 303, >5 years: 72, NS: 15 Severity: NS | Data collection: Cross‐sectional survey Measures: Southampton Needs Assessment Questionnaire for People with Stroke which incorporated SIPSO | Outcome measure testing Patient group: aged 18–65; 1–10 years post‐stroke Psychometric testing: content validity and test–retest reliability | Internal reliability: ICC 0.91 (95% CI, 0.90–0.92), item to total SIPSO correlations: 0.52–0.83 (range) Construct validity: good – those with poorer employment, mobility and sex‐life outcomes had lower SIPSO scores than those with better outcomes. Test–retest reliability: good – ICC for total score 0.96 (0.92–0.98), Physical component subscale 0.94 (0.88–0.97), Social component subscale 0.95(0.90–0.98). Excellent reliability and validity used with younger adults. |

| Ljungberg et al. (2001) Sweden | To develop a rehabilitation programme in which stroke team, patient and family act as partners in the process | Number: Intervention group (IG): 32; Control group (CG): 9 Age: IG: 72 (mean), CG: 72 (mean) Gender: IG: 14 (male),18 (female) CG: 6 (male), 3 (female) Ethnicity: IG: NS, CG: NS Marital status: Married: 16, Single: 6 Employment: NS Time: NS Severity: NS | Data collection: semi‐structured interviews at 5 time points, up to 12 months post‐discharge Measures: Functional Independence Measure, Quality from the Patient’s Perspective, Life satisfaction measure, study‐specific questionnaire to evaluate the education programme | Rehabilitation therapy component Focus: to improve functional ability and life satisfaction Location: own home or frail elderly unit Duration: 4 weeks Delivery: patient and family Content: collaborative care planning, therapy input, social support, leisure activities, security at home Staff: members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT), social work support services Staff training: stroke rehabilitation and care Education programme Focus: increase stroke knowledge, increase social support networks, improve daily life skills Location: NS Duration: five 2‐h sessions Delivery: group sessions (6–8 people); Content: as above Staff: MDT members Staff training: as above | Rehabilitation therapy component Functional ability: Intervention group had improved functional ability, participated in activities and were more active after 4 weeks, than the control group Life satisfaction: at 4 weeks: patients: 4.0 (mean), families: 3.8 (mean); at 6 months: patients: 3.1 (mean), families: 3.1 (mean); at 1 year patients: 3.5 (mean), families: 3.3 (mean) Admission time: shortened by 33% in the intervention group Education programme Respondents: n = 13 New knowledge: 8 Network enhancement: 10 |

| The authors suggest that patients were given the opportunity to make their own decisions, to be more active and motivated, and were able to carry out their preferred activities in their own home, which led to improvement in daily life function | |||||

| Long et al. (2008) UK | To develop and validate a measure of communication effectiveness for people with communication problems post‐stroke | Number: 102 Age: 21–44: 6, 45–64: 31, 65–74: 28, ≥75: 33 Gender: 61 (male), 41 (female) Ethnicity: NS Marital status: NS Employment: Employed: 33, Unemployed: 69 Time: NS Severity: BI: 17 (mean) | Data collection: semi‐structured interviews; structured questionnaire delivered twice within weeks Measures: BI, Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test | Outcome measure development Focus: communication support Patient group: general stroke population Assesses: communication effectiveness following stroke Items: 29 Completion time: 20–25 min (median) – clinician support required; communication prompts are provided Psychometric testing: acceptability, reliability, item analysis Patient‐centred: patient’s perspective of communication effectiveness following stroke | Acceptability: good – few missing values, sample spread 28–100% Internal consistency and test–retest reliability: α = 0.95; ICC = 0.90 and subscales: α = 0.65–0.93; ICC = 0.72–0.88 Item analysis: 9 redundant items Revised scale (20 items): Internal consistency and test–retest reliability: α = 0.83–0.92; ICC = 0.72–0.88 |

| Nordehn et al. (2006) USA | To explore patients’ and family members’ views of patient‐centred communication | Number: 9 Age: 40–75 (range) Gender: 6 (male), 3 (female) Ethnicity: Caucasian Marital status: NS Employment: NS Time: NS; Severity: ‘mild‐severe’ | Data collection: one‐off focus groups Measures: N/A | N/A | Two key themes: Patients and families desire to be treated with respect It is important to allow adequate time for a person with a speech disorder to communicate |

| Pound et al. (1998) UK | To explore patients’ experiences of the consequences of stroke | Number: 40 Age: 71 (mean) Gender: 21 (male), 19 (female) Ethnicity: White: 35, Bangladeshi: 3, Caribbean: 2 Marital status: Married: 19 Employment: Last employment was manual n = 30 Time: 10 months Severity: ‘less disabled’ | Data collection: one‐off semi‐structured interviews Measures: N/A | N/A | Key themes: Difficulty leaving the house, Unhappiness, Housework, Leisure activities, Walking, Talking, Washing and bathing, Relationships, Confusion/memory problems |

| Secrest (2000) USA | To investigate the experiences of primary support persons of stroke survivors | Number: 12 (spouses/carers) Age: 40–72 Gender:2 (male), 8 (female) Ethnicity: NS Marital status: Married: 8 Employment: Employed: 5, Retired early: 4 Time: 2–4 years Severity: NS | Data collection: one‐off semi‐structured interviews Measures: N/A | N/A | Phenomenological analysis revealed: the experience of being primary caregiver is grounded in the relationship in time, i.e. primary caregivers spoke of themselves in relation to others, rather than of themselves as individuals Against this ground emerged themes of fragility (fragility of life); vigilance (watching over the person who has had a stroke); loss (loss of an aspect of the person as they were before stroke); responsibility (changed roles in the relationship) |

| Studenski et al. (2001) USA | To provide patients and their families with information regarding recovery prognosis | Number: 413 Age: 69.9 (mean) Gender: NS Ethnicity: African‐American: 83 Marital status: NS Employment: NS Time: 3–14 days Severity: NS | Data collection: focus groups at 4 time points over 6 months Measures: NIHSS, OPS, BI, Lawton‐ Brodie ADL | Focus: Estimation of recovery rates in relation to five patient‐centred outcomes: severe dependence in self‐care, full independence in self‐care, independence in meal preparation, managing medications, community mobility Patient‐centred: information desired by patients and families | Baseline OPS predicted significant differences in recovery rates for all 5 outcomes (P < 0.0001) at 3 and 6 months Self‐care dependence: present at 3 months in only 3% of people with baseline OPS of ≤3.2 compared with over 50% with OPS ≥4.8 Independent self‐care, meal preparation and medications: present in 80% of OPS ≤ 2.4 compared with 20% when OPS was ≥4.4 Community mobility: achieved by 50% with OPS ≤ 2.4 compared with 3% when OPS was ≥4.4 |

| Trigg et al. (1999) UK | To ensure the content validity of a new measure: the Subjective Index of Physical and Social Outcome | Number: Age: 30 Gender: 17 (male), 13 (female) Ethnicity: NS Marital status: Married: 22, Single: 8 Employment: NS Time: ≤6 months post‐discharge from rehabilitation unit Severity: NS | Data collection: one‐off semi‐structured interviews Measures: N/A | N/A | Outcome measure development: 4 main categories were identified: Activities affected by stroke, Leisure affected by stroke, Interaction affected by stroke, Environment affected by stroke |

| van Bennekom et al. (1996) Netherlands | To explore the appropriateness of using the Rehabilitation Activities Profile (RAP) to identify disabilities/problems from the perspective of patients following stroke | Number: IG: 33, CG: 24 Age: IG: 67.9 (mean), CG: 70.2 (mean) Gender: IG: 16 (male),17 (female), CG: 13 (male), 11 (female) Ethnicity: NS Marital status: Living with partner: IG: 24, CG: 11 Employment: Employed: IG: 6, CG: 7 Time: 6 months (both groups) Severity: NS | Data collection: one‐off structured interviews Measures: RAP | N/A | Patient‐perceived problems: Walking, Using transport, Leisure activities, Relationships (friends/ acquaintances) Perceived problem scores did not relate in a uniform way to disability scores. The proportions of patients with perceived problems showed statistically significant differences between IG and CG for 15 of 21 items (P < 0.02). Cumulative relative frequency distributions showed IG described significantly more problems than CG (P < 0.01) |

| Wressle et al. (1999) Sweden | To explore patients’ and professionals’ perspectives of goal setting stroke rehabilitation | Number: 5 Age: 82 (mean) Gender:1 (male), 4 (female) Ethnicity: NS Marital status: NS Employment: NS Time: NS Severity: NS | Data collection: 1–2 semi‐structured interviews Measures: N/A | N/A | Patients wanted to be: Able live at home; Attain pre‐stroke status; Physically active and mobile Able to travel (this was associated with a sense of freedom) Patents described: Changes to their role (inside and outside the family); Insecurity and fear Lack of self‐trust. Patients did not participate in goal‐setting; assumed a passive role when helpoffered |

Location

Only one study was conducted solely in an acute care setting, 52 four studies were in rehabilitation units; 11 , 18 , 48 , 50 four in a combination of hospital and community settings, 13 , 42 , 51 , 53 and 12 were conducted in community settings. 20 , 22 , 28 , 30 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 54 , 55 , 56 It is hypothesized that this tendency to involve patients as research participants once they are out of the acute phase may reflect the patient‐centred topic of the review. HPs considered implementation of patient‐centred care more feasible once patients were medically stable and had some spontaneous recovery of function, including speech. 52

Inclusion/exclusion of people with aphasia

Stroke patients with communication impairments are frequently excluded from participation in stroke research, 57 a finding supported by the results of this review, in which only three of the 21 studies actively involved, or were specifically focused on, participants with communication impairments. 28 , 45 , 46 However, a further four reported including people with aphasia. 30 , 44 , 50 , 53 This issue is discussed in detail in relation to the communication theme in the thematic analysis section.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment revealed the variable quality of the papers included in the review (Table 2). 35 However, it could be argued that this process provided an insight into the quality of reporting, rather than providing an assessment of the quality of conduct of primary research, as the quality analysis reflected changing trends evident in reporting conventions. 58

Identification of patient‐centred outcome measures

Stage 5 analysis revealed that the 21 studies had used a variety of outcome measures to describe their participants in terms of, for example, function and stroke severity (see Table 3, column 4), e.g. the Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living 59 and the Rankin Scale. 60 As these outcome measures were designed to measure outcomes of importance and relevance to clinicians, auditors and researchers rather than to identify patient‐centred goals and outcomes, 21 , 29 they did not meet the review criteria, i.e. stroke specific and patient‐centred (Box 1). However, studies that used clinician‐oriented outcome measures to describe their sample, but which were concerned with the development or evaluation of patient‐centred outcome measures or interventions, were eligible for inclusion in the review.

In Stage 5, three studies that reported the development of new outcome measures and which met the patient‐centred criteria of the review were identified, namely Subjective Index of Physical and Social Outcome (SIPSO), 30 the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS), 20 both of which are comprehensive measures designed to encompass a range of outcomes following stroke, including social and recreational outcomes, and Communication Outcome after Stroke scale (COAST), 28 which is concerned with individual patient’s perceptions of the effectiveness of their communication skills, following stroke. Details of the instruments are provided in Table 3.

Identification of patient‐centred interventions

Four of the 21 studies evaluated interventions. 41 , 42 , 45 , 50 , 53 These interventions were a 2‐day residential family intervention for people with aphasia and their family carers, which aimed to equip carers with improved communication skills, 45 a psychosocial intervention (Families in Recovery from Stroke Trial) designed to improve social support and self‐efficacy in older patients with stroke, 41 , 42 and a family‐centred home rehabilitation programme 53 that explored the effects of a home rehabilitation programme on functional outcomes informed by patients’ perspectives. 50 Key elements of the interventions included delivery in the patient’s own home, 41 , 42 , 50 , 53 the intensive nature of the intervention, 41 , 42 , 45 , 50 , 53 meaningfulness and relevance of content and mode of delivery, 41 , 42 , 50 , 53 close involvement of family members 41 , 42 , 45 , 53 and delivery by trained experts. 41 , 42 , 45 , 53 Details of the interventions are provided in Table 3.

Results of the thematic analysis

The 21 studies included in the review were subjected to a process of thematic analysis. Ten themes were identified and were encompassed within three broad categories: meaningfulness and relevance, quality, and communication. These three broad categories, or overarching themes, formed a theoretical framework of patient‐centred practice in stroke rehabilitation (Box 2). The three overarching themes are described here along with supporting evidence extracted from Stage 4 review papers.

| Box 2 Theoretical framework: patient‐centred practice in stroke rehabilitation |

| The meaningfulness and relevance of rehabilitation activities |

| The need to understand the experiences of patients |

| The need to ascertain the priorities, concerns and goals of patients |

| Measures that support patient‐centred practice |

| The need to measure patient‐centred practice |

| The need to understand the experiences of carers |

| Family‐centred interventions |

| Quality |

| Quality of participation in activities |

| Communication |

| Including communication‐impaired adults |

| Excluding communication‐impaired adults |

| Communication impairment: a barrier to the provision of patient‐centred care |

Meaningfulness and relevance

Stroke HPs have described a need for rehabilitation that is concerned with determining the needs and priorities of patients, 13 , 18 , 28 , 49 and subsequently working with patients, on an individual basis, to develop goals that reflect those needs and priorities. 30 , 44 , 45 The evidence indicates that if patients understand that rehabilitation is tailored to their needs and priorities, they are better able to actively engage with that process, understanding it to have meaning for them, and relevance to daily life. 13 , 43 Ekstam et al.’s 50 findings indicated that patients’ perceptions of functional competence were likely to be enhanced if they were involved in rehabilitation activities that had context‐specific meaning and relevance. In contrast, patients who feel that rehabilitation is being done to them rather than for them or with them feel disempowered and may disengage with the process, assuming a passive role as the rehabilitation programme runs its course. 11 , 14 , 18

However, to support patient‐centred practice, HPs require access to patient‐centred outcome measures that will help them to ascertain patients’ goals and monitor the patient‐centred nature of their practice. 11 , 45 , 54 In particular, the lack of a patient‐centred measure specific to the specialty of stroke and stroke‐related communication impairment has been noted (e.g. 20 , 28 , 30 ). Stroke HPs have also articulated a need for measures that will help them to assess and monitor the patient‐centred nature of their practice. 11 , 56 They questioned whether the priorities and goals of patients differed from those of HPs. A discrepancy between the two would suggest that HPs did not ascertain patients’ priorities before they developed therapy goals and initiated programmes of therapy, and therefore, their practice was not patient‐centred. 11 , 45 , 54 , 56 Wressle et al. 11 acknowledged that contemporary practice was physician‐led and tended to focus on impairments. A qualitative study to explore the rehabilitation process from the patients’ perspectives was undertaken. The findings demonstrated that patients did not participate in goal setting; in fact, they demonstrated ‘resigned passivity’, and therefore, the therapists’ practice failed to meet patient‐centred criteria. 11

As described previously, HPs need to be able to ascertain patients’ priorities to deliver services that patients perceive to be meaningful and relevant. 18 Similarly, stroke HPs argue that rehabilitation is more likely to be effective if families/carers are actively engaged in the process, and active engagement requires that HPs gain an understanding of the perceived needs of families/carers, as well as those of patients. 18 , 43 , 53 Findings from Grant and Davis’ 44 qualitative study, which explored the meaning of self‐loss as experienced by family caregivers, highlighted discrepancies between stroke care delivery and the perceived needs of families/carers. Secrest 43 aimed to determine how to effectively engage families/carers in the rehabilitation process, and undertook a qualitative study that aimed to gain an insight into the experience of caring, from the perspective of carers. She concluded that nurses should assist patients and families/carers to design mutually agreed strategies and goals. Ljungberg et al. 53 recognized a need for patients and families to be active participants in programmes of rehabilitation and therefore undertook to design and evaluate a family‐centred home rehabilitation programme, tailored to specific needs and priorities of individual families. The results demonstrated improved patient motor function, which the researchers attributed to high levels of engagement and motivation generated in patients and their families by the family‐centred nature of the rehabilitation programme.

Quality

The term ‘quality’ is used to describe the importance that patients attach to being able to conduct activities in the same manner as prior to their stroke. If a patient is able, or enabled, to engage in an activity, it is not the conduct of the activity that is important to them, it is the manner in which they conduct that activity that is important. Trigg et al. 30 and Harris and Eng 47 found that people prioritized their performance of certain day‐to‐day tasks over other self‐care activities and that often they were dissatisfied with the quality of their conduct of those tasks. Patients valued more than their ability to participate in an activity; they prized the quality of their ability to participate in the activity, i.e. people wanted to be able to carry out activities in the same manner as prior to their stroke. 18 , 48 , 49 For example, the quality of their manner of walking and bathing was highly valued by the participants in Pound’s study. 49 Clark and Rugg 48 found that occupational therapists focused on the achievement of independence in an activity such as toileting, whereas patients focused on their ability to perform toileting in the manner they did prior to their stroke: ‘the patients … placed considerable emphasis on complying with the usual occupational form of toileting’ (p.170). 48 Trigg et al. 30 found that ‘the quality of activities is often as important to a person as is the frequency of participation and can have a significant influence on whether an activity is continued after stroke’ (p.350). 30 These findings highlight the need for outcome measures to incorporate a subjective assessment of patient’s perceptions of the quality of post‐stroke activities and interactions. 30 , 49

Communication

The broad theme of ‘communication’ encompasses inclusion/exclusion of people with aphasia and other stroke‐related communication impairments from active involvement in stroke research and stroke rehabilitation. It also encompasses the issue of stroke‐related communication impairment as a barrier to effective communication between HPs and patients, and between family members and ‘patients’.

Participants with aphasia were involved in seven of the studies reported in the papers included in the review. 28 , 30 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 50 , 53 However, only three studies focused specifically on adults with communication impairments and/or their families. 28 , 45 , 46 Fox et al.’s study 45 focused on the needs of family caregivers of adults with aphasia; however, data were collected from the caregivers only. Nordehn et al. 46 gathered information from adults with stroke‐related communication impairments regarding their experiences of communicating with HPs. Their study incorporated several design features that facilitated involvement of adults with communication impairments, e.g. conducting focus groups with a previously established support group and providing written information to support verbal information. Findings revealed that most comments were generic and not specific to the individual’s communication impairment. For example, issues highlighted included the need for respect, the importance of eye contact, being listened to and the need for thorough explanations, which are elements crucial to delivery of patient‐centred care that have been identified previously in the literature. 5 A minority of comments related specifically to communication impairments. These included a tendency for HPs to ignore people with communication impairments in favour of a communication‐unimpaired spouse. Long et al.s’ 28 study, as described above, was concerned with the need to develop an outcome measure that is capable of measuring communication effectiveness, from the perspective of patients with stroke‐related communication impairments.

Four other studies involved people with aphasia and other stroke‐related communication impairments but did not provide details as to how meaningful participation was facilitated. 30 , 44 , 50 , 53 For example, Ljungberg et al. 53 reported omitting open‐ended questions in their structured interviews ‘because of fear of difficulties in obtaining answers from patients with aphasia’ (p.51). 53 However, the authors went on to report that the involvement of patients with aphasia in their study constituted ‘no problem … provided they were given sufficient time to answer the questions and the interviewer ensured a supportive environment’ (p.51). 53 Unfortunately, no detail was provided of what constituted a ‘supportive environment’.

In contrast, five authors reported participation criteria that excluded people with aphasia and other communication impairments; 18 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 56 a further two authors reported excluding people with severe communication impairments. 13 , 41 , 42 Cup et al. 56 stated, ‘Inclusion criteria were: … communication (understanding and producing language) … sufficient to participate in two additional interviews (judged by the research occupational therapist)…’ (p.404). 56 Harris and Eng 47 stipulated in their inclusion criteria that participants required the ability ‘to communicate sufficiently to participate in an interview’ (p.172). 47 Glass et al. 41 , 42 excluded adults with ‘severe impairments in cognition and language’ from their PSI study because they would be ‘unlikely to benefit from the intervention’ (p.889). 42 Unfortunately, no argument is presented in support of this contentious statement. Five authors failed to provide sufficiently detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria to enable the reader to determine whether people with communication impairments had been included (i.e. 11 , 20 , 51 , 52 , 54 ); the data gathered by Kersten et al. 55 did not enable them to ascertain whether people with aphasia had completed and returned their questionnaire. As Secrest 43 interviewed only family carers, her study was not included in this theme.

Following stroke, communication impairment may constitute a barrier to the delivery and receipt of patient‐centred care. In terms of care delivery, Burton 18 and Jansa et al. 52 described the difficulty associated with actively involving patients in their own care in early stages of recovery, often as a consequence of stoke‐related communication impairments. In terms of the receipt of patient‐centred care, Nordehn et al.s’ 46 study demonstrated that patients perceive HPs as struggling to communicate in a patient‐centred way, particularly with patients who have stroke‐related communication impairments. Ellis‐Hill et al. 13 highlighted the importance of effective communication between HPs and patients to ensure that patients and their families are actively and meaningfully involved in planning continued access to stroke services, following discharge from hospital. In terms of communication between people with aphasia and their families, effective communication methods need to be taught and implemented early in the rehabilitation process. Fox et al. 45 found that, once communication methods are established, carers are likely to be resistant to learning new, more effective methods.

The development of a stroke‐specific definition of patient‐centred care

The theoretical framework of patient‐centred practice in the specialty of stroke described earlier (Box 2) was developed as a result of qualitative analysis of the 21 studies included in the review. This evidence‐based framework highlighted ‘meaningfulness and relevance’, ‘quality of participation’ and ‘communication’ as elements essential to the delivery of patient‐centred stroke care. The authors compared the stroke‐specific theoretical framework generated as a result of the thematic analysis process with Long’s 16 generic definition of patient‐centred outcome measures (Box 1) and identified that although ‘meaningfulness and relevance’ were incorporated into Long’s definition, ‘quality of participation’ and ‘communication’ were absent. Subsequently, Long’s generic definition was reworked to incorporate these essential, stroke‐specific elements to produce an evidence‐based, stroke‐specific definition of patient‐centred care against which HPs are able to benchmark practice and any outcome measures used to support practice (Box 3). This definition was an unexpected but important product of the review process.

| Box 3 An evidence‐based, stroke‐specific definition of patient‐centred care |

| Identifies individuals’ communication skills and utilizes appropriate and effective communication strategies in all interactions between the health‐care professional and the individual |

| Identifies outcomes that are valued and prioritized by individuals |

| Identifies outcomes that reflect the desired quality of participation |

| Monitors and measures outcomes at appropriate times and points in the rehabilitation process |

| Uses the resultant information to inform the patient/health‐care professional’s decision‐making process |

Discussion

In response to a UK policy imperative, HPs have articulated a desire to shape services according to a model of patient‐centredness that is responsive to the needs and priorities of service users. However, tensions between the aims and priorities of HPs and those of patients and their families have been described as presenting a barrier to successful patient‐centred outcomes. 5 , 8 , 13 Other identified barriers include lack of appropriate outcome measures with which to monitor and measure practice. 5 , 14 , 20 Although stroke HPs have expressed a need for definitions and outcome measures that will support their efforts to deliver patient‐centred care, the issue of whether disease‐specific definitions and outcome measures are required, or indeed are antithetic to the concept of patient‐centredness, has been raised. 5 Some studies have identified that generic patient‐centred outcome measures may not be the best way forward. 5 , 9 There may be a need for more condition‐specific tools that are founded on generic principles of patient‐centredness because, although barriers to implementation and delivery are likely to be generic and similar across specialties, the most appropriate or effective means of addressing them may vary. We suggest that patient‐centred care requires the tailoring of measures and interventions to suit specific needs and priorities of patients and their families. This review has demonstrated that systematic review methods can be used to identify measures and interventions required to support HPs in the delivery of condition‐specific patient‐centred care along with important aspects of patient‐centred approaches that need to be included in further development of patient‐centred measures and interventions.

Using the specialty of stroke as an example, we conducted a systematic review to identify stroke‐specific patient‐centred outcome measures and interventions. The review identified three measures, 20 , 28 , 30 and four interventions, 41 , 42 , 45 , 50 , 53 which were developed to reflect and respond to patients’ and families’ needs and priorities. The review also retrieved papers that reported results of primary research designed to ascertain the needs and priorities of patients with stroke.

A range of outputs were derived from the review 61 including identification of stroke‐specific patient‐centred outcome measures and key elements of stroke‐specific patient‐centred interventions, a theoretical framework of stroke care/rehabilitation, and a comprehensive definition of patient‐centred care (Box 3), specific to the specialty of stroke. These review‐derived outputs are important because they represent the constituent parts of a patient‐centred toolbox for HPs that can be used to support delivery of patient‐centred rehabilitation, i.e. rehabilitation that meets the needs and priorities of patients and their families, and responds to changing needs and priorities, as patients and their families move along the recovery trajectory. 62 The contents of the toolbox may also be used to support a range of patient‐centred activities, in a range of stroke settings, including development of a patient‐centred culture of care and patient‐centred team working. Specifically, this mixed‐method review informed the development of a definition of patient‐centred stroke care that provides HPs with a benchmark against which they can measure their practice, and that has the potential to foster a culture of patient‐centred team working and care design and delivery. For example, the review‐derived definition supports the use of stroke‐specific patient‐centred outcome measures, such as those identified by the systematic review, which will help stroke HPs to measure patient‐centred outcomes and monitor the relevance of their practice to patients’ and families’ changing needs and priorities.

Limitations

The review was conducted as part of a programme of PhD research, 35 where only ML worked on every stage of the review process. Quality criteria for the conduct of systematic reviews describe the need for a minimum of two reviewers and process transparency. 32 , 63 Efforts were made to ensure rigorous and systematic conduct of this review by means of discussion at every stage of the process with experienced systematic reviewers. During Stage 4, ten papers included in the review were assessed independently by an experienced systematic reviewer. In terms of transparency, every detail of the review process was recorded and is available for scrutiny. 35

Conclusion

To deliver effective patient‐centred care, HPs need to be working in a culture that supports such an approach and they need to be appropriately equipped. Using systematic review methods, we have developed a toolbox that supports delivery of patient‐centred care in stroke settings. The toolbox includes a robust and comprehensive benchmark definition of patient‐centred care, identifies key components of patient‐centred rehabilitation interventions and comprehensive patient‐centred outcome measures that are sensitive to change over time. Although the need for condition‐specific definitions and measures may be contested, this example from the specialty of stroke demonstrates that it is possible to develop and assemble a patient‐centred toolbox that may be used to develop and support a culture of patient‐centredness, development, delivery and measurement of patient‐centred care and patient‐centred interventions, thus ensuring the meaningfulness, relevance and effectiveness of the stroke rehabilitation process, from the perspective of patients and their families.

Conflicts of interest

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Source of funding

Maggie Lawrence received a 3‐year Research Studentship from the Chief Scientist Office, Scotland. We also acknowledge the support received from the Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professions Research Unit, Glasgow Caledonian University, in particular from Professor Kate Niven, Dr Marian Brady and Kirsty McLauglan.

References

- 1. Department of Health . The New NHS: Modern Dependable. London: TSO, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health . Patient and Public Involvement in the New NHS. London: Department of Health, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Department of Health . Creating a Patient‐led NHS: Delivering the NHS Improvement Plan. London: Department of Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Department of Health . High Quality Care for All – NHS Next Stage Review Final Report. London: Department of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mead N, Bower P. Patient‐centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Social Science & Medicine, 2000; 51: 1087–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kennedy I. Patients are experts in their own field. BMJ, 2003; 326: 1276–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. UK Government . Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2007/28/contents/enacted, accessed 10 April 2010.

- 8. Gillespie R, Florin D, Gillam S. How is patient‐centred care understood by the clinical, managerial and lay stakeholders responsible for promoting this agenda? Health Expectations, 2004; 7: 142–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lewin S, Skea Z, Entwistle VA, Zwarenstein M, Dick J. Interventions for providers to promote a patient‐centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2001; Issue 4. Art. No.: CD003267. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mead N, Bower P. Patient‐centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: a review of the literature. Patient Education and Counseling, 2002; 48: 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wressle E, Öeberg B, Henriksson C. The rehabilitation process for the geriatric stroke patient‐an exploratory study of goal setting and interventions. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1999; 21: 80–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cott C, Wiles R, Devitt R. Continuity, transition and participation: preparing clients for life in the community post‐stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2007; 29: 156–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ellis‐Hill C, Robison J, Wiles R et al. Going home to get on with life: patients and carers experiences of being discharged from hospital following a stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2009; 31: 61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Redfern J, McKevitt C, Wolfe C. Risk management after stroke: the limits of a patient‐centred approach. Health, Risk & Society, 2006; 8: 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stroke Unit Trialists’ Collaboration . Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD000197. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000197.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Long A. The User’s Perspective in Outcome Measurement: An Overview of the Issues. 8. Leeds: UK Clearing House on Health Outcomes, University of Leeds, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goodrich J. Exploring the wide range of terminology used to describe care that is patient‐centred. Nursing Times, 2009; 105: 14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burton C. Living with stroke: a phenomenological study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2000; 32: 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Visser‐Meily A, Post M, Gorter J et al. Rehabilitation of stroke patients needs a family‐centred approach. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2006; 28: 1557–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duncan P, Wallace D, Studenski S et al. Conceptualization of a new stroke‐specific outcome measure: the Stroke Impact Scale. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 2001; 8: 19–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dowswell G, Lawler J, Dowswell T et al. Investigating recovery from stroke: a qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2000; 9: 507–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kersten P, Low J, Ashburn A et al. The unmet needs of young people who have had a stroke: results of a national UK survey. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2002; 24: 860–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blickem C, Priyadharshini E. Patient narratives: the potential for ‘patient‐centred’ interprofessional learning? Journal of Interprofessional Care, 2007; 21: 619–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brott T, Adams H, Olinger C et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke, 1989; 20: 864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mahoney F, Barthel D. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Maryland State Medical Journal, 1965; 14: 61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Granger C, Hamilton B, Keith R et al. Advances in functional assessment for medical rehabilitation. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 1986; 1: 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holbrook M, Skilbeck C. An activities index for use with stroke patients. Age and Ageing, 1983; 12: 166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Long A, Hesketh A, Paszek G et al. Development of a reliable self‐report outcome measure for pragmatic trials of communication therapy following stroke: the Communication Outcome after Stroke (COAST) scale. Clinical Rehabilitation, 2008; 22: 1083–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kjellström T, Norrving B, Shatchkute A. The Helsingborg Declaration 2006 on European Stroke Strategies. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 2007; 23: 229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Trigg R, Wood V, Hewer L. Social reintegration after stroke: the first stages in the development of the Subjective Index of Physical and Social Outcome (SIPSO). Clinical Rehabilitation, 1999; 13: 341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harden A. Extending the boundaries of systematic reviews to integrate different types of study: examples of methods developed within reviews on young people’s health In: Popay J. (ed.) Moving Beyond Effectiveness in Evidence Synthesis. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006: 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination University of York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Outpatient Service Trialists . Therapy‐Based Rehabilitation Services for Stroke Patients at Home. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2003; Issue 1. Art. No. CD002925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Blackwell, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lawrence M. Patient‐Centred Stroke Care: Young Adults and their Families, PhD thesis. Glasgow: Glasgow Caledonian University, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jackson J, Kinn S, Dalgarno P. Patient‐centred outcomes in dietary research. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 2005; 18: 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Joanna Briggs Institute . Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2008 edition. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2008. http://www.joannabriggs.edu.au/Documents/JBIReviewManual_CiP11449.pdf, accessed 10 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garcia J, Bricker L, Henderson J et al. Women’s views of pregnancy ultrasound: a systematic review. Birth, 2002; 29: 225–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C et al. Evaluating Meta‐Ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Social Science & Medicine, 2003; 56: 671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thomas J, Harden A, Oakley A et al. Integrating qualitative research with trials in systematic reviews. BMJ, 2004; 328: 1010–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Glass T, Dym B, Greenberg S et al. Psychosocial intervention in stroke: Families in Recovery from Stroke Trial (FIRST). American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 2000; 70: 169–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Glass T, Berkman L, Hiltunen E et al. The Families in Recovery From Stroke Trial (FIRST): primary study results. Psychosomatic Medicine, 2004; 66: 889–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Secrest J. Transformation of the relationship: the experience of primary support persons of stroke survivors. Rehabilitation Nursing, 2000; 25: 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grant J, Davis L. Living with loss: the stroke family caregiver. Journal of Family Nursing, 1997; 3: 36–56. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fox L, Poulsen S, Bawden K et al. Critical elements and outcomes of a residential family‐based intervention for aphasia caregivers. Aphasiology, 2004; 18: 1177–1199. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nordehn G, Meredith A, Bye L. A preliminary investigation of barriers to achieving patient‐centered communication with patients who have stroke‐related communication disorders. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 2006; 13: 68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Harris J, Eng J. Goal priorities identified through client‐centred measurement in individuals with chronic stroke. Physiotherapy Canada, 2004; 56: 171–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Clark J, Rugg S. The importance of independence in toileting: the views of stroke survivors and their occupational therapists. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2005; 68: 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pound P, Gompertz P, Ebrahim S. A patient‐centred study of the consequences of stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation, 1998; 12: 338–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ekstam L, Uppgard B, von Koch L et al. Functioning in everyday life after stroke: a longitudinal study of elderly people receiving rehabilitation at home. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 2007; 27: 434–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]