Abstract

Context The debate over primary care reform in France, as in most OECD countries, centres on questions about efficacy and accessibility. Do these reforms actually respond to the users’ concerns?

Objective The objective of this study was to identify the importance that users attribute to different aspects of general practice (GP) care.

Design The method used was a variant of the classical Delphi approach, called Delphi ‘ranking‐type’. Between May and September 2009, 74 experts aged over 18 were recruited by ‘snowballing’ sampling. Three iterative rounds were required to identify the core aspects through a consensus‐building approach.

Results It is shown that users attribute a very high importance to the ‘doctor–patient relationship’ dimension. The following aspects ‘GP patient information about his/her illness’, ‘Clarity of communication and explanation’, and ‘Whether the GP seemed listen to the patient’ were evaluated by 96% of the experts as being of high importance. The coordination of GP was also considered as a very important aspect for 85% of the experts. In contrast, the aspects that belong to the organizational dimension appeared to be of relatively low importance for users.

Conclusions Our results support a comprehensive approach of care and argue in favour of care reorganization following the patient‐centred model. To promote organizational care reforms through the prism of the doctor–patient relationship could thus be a fruitful way to insure a better quality of care and the social acceptability of the reforms.

Keywords: Delphi technique, doctor–patient relationship, general practice care, health care reforms, patients’ priorities

Introduction

The proportion of young physicians in France entering general practice (GP) is declining. The ratio of general practitioners (GPs) to the national population has decreased. At the same time, demand for care has risen steeply, in line with the ageing of the population and the increased number of chronic ailments. 1 Questions are being raised about GP accessibility and availability in a number of geographical zones, especially in rural areas and low‐income urban communities. 2 Such problems of medical demographics and health‐care organization are not specific to France: the trend is comparable in most OECD countries (The OECD is an international organisation with 34 member countries among the world's most advanced countries); 3 the re‐organization of GP care is being widely implemented. Different primary care models are tending to converge, 4 particularly towards doctors working in group practices, development of IT systems and providing patient‐centred care. Primary health‐care reform is a major issue in the efficiency of heath care systems. 5

But do these changes really address users’ concerns? Today, the patient’s perspective is accepted as a key condition of the effectiveness of GP reforms. Failure to engage with the patient’s agenda can lead to misunderstanding, dissatisfaction, poor health outcomes and inadequate use of medical resources. 6 , 7 In many OECD countries, there is an increasing demand for responsiveness to patients’ needs. 8 For example, in the UK, the white paper ‘Equity and Excellence: Liberating the National Health Service’ sets out the government’s vision for patients to have greater choice and control over their care and to create an NHS in England that truly responds to patients’ needs and preferences.

In the context of modifying the health care offered, the objective of this study was to determine users’ concerns, by identifying what they perceived as the most important aspects of GP care, recognizing its multi‐dimensional nature (accessibility; continuity; the doctor–patient relationship; medical–technical care; the organization of care). According to a varied international literature, we anticipated that users would emphasize aspects that involved the doctor–patient relationship. 9

For this purpose, we used a Delphi method to obtain user‐validated consensual results. In this article, we then discuss in the light of the reforms underway in OECD countries, to ascertain the extent to which they might address users’ current concerns.

Method

The Delphi method is a technique for the indirect confrontation of opinions. It is used to obtain consensus in a panel of ‘experts’ (in our case, a sample of health‐care users) through a series of ‘rounds’ in which information is transmitted to the users via anonymous questionnaires, which contain these diverging opinions. 10 We used a variant of the initial Delphi method, called the ‘ranking‐type’ Delphi approach, 11 , 12 which aims to develop group consensus around the relative importance of issues. Users were asked to participate in three iterative rounds. The literature indicates that it is preferable not to pursue the iterative process through a fourth round, to avoid a forced convergence of answers. 13 In the first round, the Delphi method can either be based on an initial stage involving open‐ended questions for generating aspects, or a predetermined list of aspects. In this study, we adopted the latter approach.

The first round consisted of rating the items. It was based on a questionnaire drawn up from a review of the literature on quality aspects of GP care. 14 , 15 , 16 This quasi‐systematic revue used two different databases (Pubmed; Science direct) with combinations of keywords [attributes; components; aspects; features] + [primary care; family practice; GP] in either the title or the abstract of the referenced article. Criteria for including items were: (i) published since 1990; (ii) in English or French; (iii) concerned with more than one aspect of general medicine care; and (iv) not limited to a single category of pathology. These criteria generated 60 references from the literature revue. This allowed for the identification of 57 aspects that we then adapted to the specificities of the French context, based on discussions within a working group and a pilot survey conducted on 20 users. This led to a final list of 40 aspects, grouped into five main dimensions (the doctor–patient relationship; continuity; accessibility; organization of care; medical–technical care). Users were then asked to rate the importance of each of these 40 aspects on a nine‐point scale, with three anchors: (1) ‘not important’; (5) ‘of moderate importance’ and (9) ‘extremely important’. Respondents were also informed they could add other aspects.

The second round consisted of selecting the items. It was based on a second questionnaire drawn up from the responses obtained from the first round, using two criteria to determine the retained aspects: they had to be both ‘consensual’ and ‘important’, i.e. to have obtained 75% of the answers in one of the three parts of the scale ([1–3], [4–6] or [7–9]) and a median score ≥8. This threshold has been shown to favour high reliability. 17 This second questionnaire was made user‐specific: for every aspect, it contained the users reply in the first round and compared his or her position on the nine‐point scale to the panel’s average reply. Users were asked to select the five aspects they considered to be the ‘most important’ amongst those proposed in this second questionnaire.

The third round consisted of ranking the items. It was based on a third questionnaire drawn up from responses obtained from the second round, by using a specific selection criterion: the responses had to have been designated by at least 33% of the users as being amongst the most important.

To avoid a possible response bias because of an order effect in the questionnaire, the aspects were presented in random order in the first and second questionnaires.

The panel of users was constituted by means of a purposive sampling procedure based on ‘user profiles’, defined according to three socio‐demographic characteristics: age (<55 vs. ≥55 years), gender and residential area (urban vs. rural). These variables were selected because of findings in international research on users’ opinions. 18 Our goal was to recruit 80 users to retain at least 50 respondents in the last round, with an expected 80% response rate in each round. Users were recruited according to the ‘snowballing’ method, which consists in identifying persons matching the selected profiles in the immediate network of contacts and then, if necessary, asking these persons to recruit others to represent the missing profiles. This method for recruiting respondents was not intended to generate a representative sample of the study population but to constitute a sample of individuals with very divergent opinions, thereby representing a wide spectre of points of view. The diversity of these views can then be indirectly confronted with each other by the Delphi method.

Once the potential users were contacted, the purpose of the survey was explained to them, along with the details of how it would be implemented. The first questionnaire was then mailed to all the candidates who agreed to participate, along with an information letter explaining the participation procedures for the first round. The same was done for the second and third rounds. In each round, the users were provided with stamped envelopes to send back the questionnaires they had filled out.

Results

Panel of users

Between May and June 2009, 74 users participated in the first round of the survey. The participation rate remained stable during the three stages of survey: 65 users participated in the last round (a participation rate close to 90% at each round). The users’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experts characteristics (n = 74)

| Characteristic | Per cent |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 45 |

| Female | 55 |

| Age (years) | |

| <55 | 54 |

| ≥55 | 46 |

| Residential area | |

| Rural | 43 |

| Urban | 57 |

| Level of education | |

| Less than high school | 41 |

| High school or higher | 59 |

| Chronic illness (diabetes, etc.) | |

| Yes | 11 |

| No | 89 |

| Perceived health | |

| Very good or excellent | 27 |

| Good | 48 |

| Satisfactory | 25 |

| ‘Médecin traitant’ (gatekeeper) | |

| With a ‘médecin traitant’ | 93 |

| Without a ‘médecin traitant’ | 7 |

| Medical office | |

| Individual practise | 38 |

| Group practise (only with GP) | 58 |

| Group practise (with GP + specialist + paramedic) | 4 |

| Length of relationship with the GP (years) | |

| <1 | 6 |

| Between 1 and 5 | 28 |

| >5 | 66 |

| Date of last consultation with the GP (days) | |

| <15 | 15 |

| Between 15 and 30 | 19 |

| Between 30 and 90 | 31 |

| >90 | 35 |

GP, general practitioner.

Round 1

Table 2 summarizes the results of the first round. Offering users the opportunity to propose new items did not lead to the identification of additional aspects. The mean score of importance (with the standard deviation) of the 40 aspects was 6.52 (0.85), varying according to the dimensions of care. The dimension ‘organization of care’ appeared to be the least important, with a mean score of 5.07 (1.13). In this dimension, the users attributed the lowest scores to the physician’s characteristics (GP gender; GP age), to those of the type of practice (multi‐disciplinary team; group practice), and to the waiting room (Things to do whilst waiting to be seen by the doctor). They attributed the highest scores to the dimension ‘doctor–patient relationship’, with a mean score of 8.05 (0.81). Based on these results, the application of our first decision‐rule made it possible to draw up the second questionnaire by identifying 14 aspects of GP care.

Table 2.

First round – rating of the 40 general practise care aspects (n = 74)

| Aspect | DIM* | Mean (SD) | Median | Distribution of the ratings along the scale (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–3 | 4–6 | 7–9 | ||||

| GP gives patient information about his/her illness† | DPR | 8.53 (1.21) | 9 | 1 | 3 | 96 |

| Knowledge of the patient’s medical history† | MTC | 8.41 (1.07) | 9 | 0 | 8 | 92 |

| GP seems to listen to the patient† | DPR | 8.32 (0.95) | 9 | 0 | 4 | 96 |

| Clarity of communication and explanation† | DPR | 8.31 (0.98) | 9 | 0 | 5 | 95 |

| Attention to the medical aspects of medical problems† | MTC | 8.11 (1.21) | 9 | 0 | 11 | 89 |

| Preventive care and health promotion† | MTC | 8.09 (1.22) | 9 | 0 | 8 | 92 |

| Amiability† | DPR | 8.05 (1.40) | 9 | 1 | 9 | 89 |

| Thoroughness of physical examinations† | MTC | 8.04 (1.37) | 9 | 0 | 14 | 86 |

| Cleanliness of facility† | OC | 8.01 (1.30) | 9 | 0 | 14 | 86 |

| Confidentiality of information† | DPR | 7.97 (1.94) | 9 | 4 | 14 | 82 |

| GP explains the purpose of tests and treatment† | DPR | 7.95 (1.33) | 8 | 0 | 14 | 86 |

| GP coordinates the different types of care† | CON | 7.81 (1.57) | 8.5 | 3 | 12 | 85 |

| Waiting time for appointment† | ACC | 7.76 (1.29) | 8 | 0 | 15 | 85 |

| Possibility of always seeing the same GP† | CON | 7.46 (1.92) | 8 | 4 | 20 | 76 |

| Shared medical decision making | DPR | 7.23 (1.92) | 8 | 4 | 26 | 70 |

| Ability to reach the GP by telephone | ACC | 7.08 (2.09) | 8 | 7 | 24 | 69 |

| Help from GP in obtaining appointment with specialist | OC | 6.88 (1.67) | 7 | 4 | 31 | 65 |

| Attention to the psychological and social aspects of medical problems | MTC | 6.80 (2.00) | 7 | 7 | 30 | 64 |

| Distance to cover | ACC | 6.73 (2.03) | 7 | 4 | 41 | 55 |

| GP is willing to make home visits | ACC | 6.73 (2.39) | 7 | 11 | 28 | 61 |

| Free access | ACC | 6.62 (2.18) | 7 | 8 | 32 | 59 |

| GP’s reputation | OC | 6.61 (2.15) | 7 | 9 | 36 | 54 |

| Attitude of office staff | OC | 6.56 (1.92) | 7 | 5 | 40 | 55 |

| Waiting time in the waiting room | ACC | 6.55 (2.18) | 7 | 9 | 24 | 66 |

| Office hours | ACC | 6.54 (2.12) | 7 | 8 | 32 | 59 |

| Amount of time spent with GP | MTC | 6.53 (2.18) | 7 | 11 | 27 | 62 |

| Cost of appointment | ACC | 6.38 (2.52) | 7 | 14 | 34 | 53 |

| GP is ready to discuss the tests, treatment, or referral that the patient wants | MTC | 6.37 (2.32) | 7 | 14 | 33 | 53 |

| Hotel aspects (parking, etc.) | OC | 6.04 (2.48) | 6.5 | 18 | 32 | 50 |

| Information on waiting time | ACC | 5.75 (2.18) | 6 | 15 | 47 | 38 |

| Knowledge of the patient’s personal history | CON | 5.72 (2.45) | 5 | 15 | 42 | 43 |

| Order a diagnostic test | MTC | 5.61 (2.97) | 6 | 27 | 26 | 47 |

| Atmosphere of facility | OC | 5.46 (2.12) | 5 | 16 | 49 | 35 |

| Comfort of facility | OC | 5.31 (1.92) | 5 | 14 | 61 | 26 |

| Prescription of medicine | MTC | 4.43 (2.51) | 5 | 35 | 43 | 22 |

| Things to do while waiting to be seen | OC | 3.70 (2.34) | 4 | 46 | 41 | 14 |

| Group practise | OC | 3.57 (2.45) | 4 | 46 | 42 | 12 |

| GP age | OC | 3.22 (2.23) | 3 | 53 | 41 | 5 |

| Multidisciplinary team | OC | 3.16 (2.57) | 1 | 61 | 24 | 15 |

| GP gender | OC | 2.27 (1.90) | 1 | 72 | 26 | 3 |

GP, general practitioner.

*Dimension of care. DPR, doctor–patient relationship; MTC, medical–technical care; OC, organization of care; ACC, accessibility; CON, continuity.

†Aspects selected for the second round.

Round 2

Table 3 summarizes the results of the second round. Amongst the five most selected aspects, three pertained to the dimension ‘doctor–patient relationship’ and two to ‘medical–technical care’. The aspect ‘GP gives patient information about his/her illness’ received a very high selection rate (70% of users). However, other aspects of GP care were also reported to be of importance by the users. More than one‐third of the users selected the aspect ‘GP coordinates different types of care’ amongst the five most important aspects. Based on these results, application of our second decision‐rule made it possible to draw up the third questionnaire by identifying seven aspects of GP care.

Table 3.

Second round – selecting of the 14 general practise care aspects (n = 70)

| Aspect | DIM* | Selection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of experts | Per cent | ||

| GP gives patient information about his/her illness† | DPR | 49 | 70 |

| Knowledge of the patient’s medical history† | MTC | 38 | 54 |

| GP seems to listen to the patient† | DPR | 31 | 44 |

| Thoroughness of physical examinations† | MTC | 27 | 39 |

| Clarity of communication and explanation† | DPR | 27 | 39 |

| GP explains the purpose of tests and treatment† | DPR | 25 | 36 |

| GP coordinates the different types of care† | CON | 25 | 36 |

| Waiting time for appointment | ACC | 20 | 29 |

| Cleanliness of facility | OC | 19 | 27 |

| Preventive care and health promotion | MTC | 19 | 27 |

| Attention to the medical aspects of medical problems | MTC | 16 | 23 |

| Confidentiality of information | DPR | 16 | 23 |

| Amiability | DPR | 15 | 21 |

| Possibility of always seeing the same GP | CON | 10 | 14 |

GP, general practitioner.

*Dimension of care. DPR, doctor–patient relationship; MTC, medical–technical care; OC, organization of care; ACC, accessibility; CON, continuity.

†Aspect selected for the third round.

Round 3

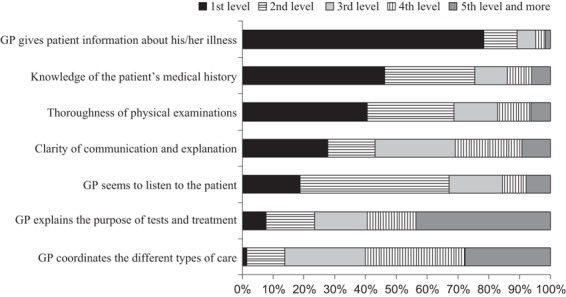

The results of users’ ranking are summarized in Fig. 1. The aspect ‘GP gives patient information about his/her illness’ appears to be the users’ first priority. Regarding the other aspects, results seem less clear in terms of the order of importance.

Figure 1.

Third round – ranking of the seven most important general practice care aspects. Percentage of experts (n = 65) who placed each aspect of general practice care at different priority level.

Discussion

In our study, users valued the majority of the aspects of GP care as important. Nevertheless, three particular results stand out. The first was the high importance that users give to the aspects concerning ‘how the consultation is conducted (or the content of the consultation)’ and more specifically information‐sharing between the patient and the physician and the technical dimension of care (thoroughness of the auscultation). Similar results were found in previous studies. 19 , 20 , 21 The international literature has generally found a relationship between patient ‘satisfaction’ and how doctors and their patients communicate with each other. 22 A second key result of our survey was the importance given by users to the coordination of care (coordination of different types of care; help in obtaining an appointment with a medical specialist) that was indicated in every round as one of the most important aspects of care. Many studies, mostly with specific clinical groups, have also explored this aspect. 23 , 24 According to Grol et al., 21 this is one of the aspects of care most sensitive to cultural differences and that varies between different health‐care systems. The third important result of our survey was the low priority given by users to the aspects relative to the type of practice (group practice, working in a multi‐disciplinary practice) and to the individual characteristics of doctors (gender, age). This result is more nuanced in the literature. This third result is consistent with certain studies 21 , 23 that shown, for example, that cooperation between GPs and other medical staff was not very important from the users’ point of view. However, multivariate‐analysis models have found that these organizational aspects of service delivery influenced users’ extent of satisfaction. For instance, the work of Haggerty et al. 25 showed that users’ confidence in first‐contact accessibility of care declined when the size of the practice increased. One can see that whilst the patients’ viewpoint has been widely studied in the international literature, the use of the Delphi method constitutes an original approach to the question. To date, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to use the Delphi method to identify patients’ priorities for GP care. A few other studies have used this method in the GP context, but generally from the perspective of health professionals (e.g. GPs, nurses), or in the context of a specific pathology (e.g. diabetes, osteoporosis), or for a particular dimension of medical care (e.g. professional training, therapeutic education). The standard approach of studying the patient perspective is to use rating‐scales of satisfaction or importance, generating a statistical response. The Delphi ‘ranking’ method allows us to obtain a point of view that is elaborated step‐by‐step and validated by users themselves, thus ensuring a high level of internal consistency. In this study, the users’ views we obtained thus correspond to those of a patient who gives high priority to the exchange of information with the GP without this being at the expense of the thoroughness of the clinical examination. The patient also wants the GP to help in navigating the health‐care system (coordination).

Our results also contribute to the worldwide issue of the extent to which primary care reforms address users’ concerns. These reforms, in large part founded on the principles adopted at the 1984 Alma Alta conference, 26 have tended to establish a model of primary care based on team working/group practice development, the increasing use of information technology, performance incentives and the regionalization of services.

In 2001, the Ontario government launched the ‘Ontario Family Health Care Network’. The key elements of this new delivery model were patient rostering (to link a patient to a single care provider), capitation payment with added incentives for prevention and other targeted services, provision of out‐of‐hours service, tele‐triage, and the extensive use of electronic medical records and linkages. 27

In 2002, Quebec’s Ministry of Health and Social Services introduced the concept of ‘Family Medicine Group’, which is an administrative arrangement for existing practices (mainly solo practices) to develop collaborative activities. Physicians are grouped together to collaborate with nurses to offer primary care services, including patient follow‐up, health promotion and preventive care, to a set of registered patients. It offers patients access to care 24 h a day, 7 days a week, through regular appointments, walk‐in clinics, home visits, and after‐hours health coverage, using telephone hot‐lines and emergency on‐call services.

In the last decade, major changes were introduced in the delivery of primary care in England. First, team work was promoted by a new General Medical Services contract with a shift from individual‐GP to practice‐based contracts. Second, the payment schema of GPs was changed with the quality and outcomes framework (QOF). The QOF provides financial incentives for GP to meet a range of clinical, organizational and patient experience criteria. Third, the primary care access was refunded, with the ‘NHS Direct Reform’ 28 , 29 that guarantees patients access to a primary care practitioner within 24 h or a GP within 48 h.

In Australia, a ‘General Practice Strategy’ was adopted in 1991 to improve the integration, quality and comprehensiveness of GP care. A major reform has been the formation of 123 ‘divisions of general practice’, which are geographically based organizations of GPs aiming to develop cooperative activities and to address health needs at the local level. 30 More recently, the Government has initiated a scheme that pays GPs to develop multi‐disciplinary patient management plans. 31

In 2002 and during the 1990s, the New Zealand government introduced a set of primary care reforms including the grouping of GPs into independent practitioner associations, the development of increasing numbers of non‐profit primary care organizations and developing performance indicators based on improvements in clinical care, referred services expenditures, access and information collection. A special organization, ‘Primary Health Care Organisations’, 32 received a capitation funding to develop ‘population‐based health promotion services’, to provide comprehensive ambulatory medical care 24 h a day, 7 days a week for enroled members, and to coordinate services for individuals.

In France, three recent reforms have been introduced (2001, 2004, 2009). The March 4, 2002 Act on ‘patients’ rights and the quality of the health system’ emphasized the importance of giving adapted medical information to patients. It stipulates that health professionals have a mandatory duty to provide information to their patients. The August 13, 2004 Act on health insurance implemented a gate‐keeping system to ‘improve the coordination and the quality of care’. Users now have to consult their ‘médecin traitant’ (a physician chosen as a referring physician) before consulting specialists, failing which their medical expenses are reimbursed at a lower rate by the health‐insurance scheme. The July 21, 2009 Act on ‘hospitals, patients, health, and territories’ defined a service delivery that addresses the local needs of the population by taking into account its specificities and constraints. In particular, the medical group practice (primary care team) is promoted to develop cooperation amongst health professionals (GPs, specialists and paramedics) to improve patient care and to combat ‘medical desertification’.

Our results suggest that these transformations can potentially respond to users’ concerns about the health care offer in general medicine. They point to an overall reorganization of primary care focusing on the patient rather than his or her ailment. This approach consists of tailoring care to meet the needs and preferences of patients. It promotes the active involvement of patients in care delivery, in developing, for example, shared decision making between the patient and the physician. These changes (patient‐focused; care over time; coordination) are generally advocated as appropriate ways to strengthen the primary care sector and hence to improve the efficiency of the overall health‐care system. 5 Moreover, these can be also a response to the GPs’ workforce issues. In the United States, it is argued that, complementary to financial initiatives, such as loan repayment schemes adopted in the recent ‘Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’ (2010), the ‘Patient‐Centred Medical Home’ can improve the attractiveness of GP with better professional conditions.

However, these transformations are not easy to implement, mainly for financial and technical reasons, depending on the present primary care organization. First, the payment scheme has to be adapted to GPs’ activities (case management and evaluation occurring outside of patient visits; time spent coordinating care with other practitioners; time spent educating patients during visits; time spent communicating with patients by phone and e‐mail). GPs also need financial help to adopt the information technology required to make efficient use of these resources. 33 Second, from an organizational point of view, the role of the GP in the accessibility of secondary and tertiary care should be clearly defined. As shown by Grumbach et al., patients recognize the value of primary care physicians coordinating their care and most of them preferred their primary care physicians to be involved in decisions about obtaining care from specialists, rather than seeking care directly from the specialists themselves. 34 Yet, the GP must not be envisaged as a ‘rationer’ of specialized care and patients must be clearly informed of the conditions of an eventual referral to a specialist and of the role of the GP. In addition to these issues, transforming primary care in the direction of a more comprehensive approach towards patients requires rethinking the sharing of the workload between health professionals. For example, it has been estimated in the United States that it would take 10.6 h per working day for a GP to deliver all the recommended care for patients with chronic conditions following the increased demands placed on primary care and 7.4 h per day more to provide evidence‐based preventive care. 35

Limitations

There are a number of limitations of our study. First, to establish a panel of users representing a wide range of opinions, selection of the users was based on three main socio‐demographic variables (age, gender and residential area). These individual characteristics were proxies of the experience of care and do not account fully for the diversity of individual points of view regarding GP care. Other variables could have been used to diversify our panel of users, mainly their health status (presence or absence a chronic disorder). However, the panel seemed well‐balanced in terms of perceived health status and social categories.

Second, several studies have shown that it is difficult to askers about the importance they assign to different aspects of care. 36 Two of the main pitfalls were the inconsistency of answers over time, respondents change their ratings without following a rational process – and the fact that respondents seemed unable to state the relative importance of care aspects when there are many of these, largely because of the cognitive complexity of the exercise. In our study, we tried to overcome these limitations by using a stepwise approach that aided the respondents to state the relative importance of GP care by gradually reducing the initial set of aspects. Moreover, in the last round, we gave the users the possibility of assigning several aspects of care to the same level of importance, to limit forced or inconsistent answers.

Third, approaching GP care independently of the specific pathologies patients presented also seemed to constitute a difficulty for the users. Other studies on patients’ points of view in GP also came up against the difficulty of appraising the effect of the motive for seeking care and found substantial variation in the answers depending, for instance, on the perceived severity of the pathology. 37 , 38 In our survey, we tried to limit the influence of a specific pathology on the users’ statements by using a label and carefully explaining the objective of our study.

Fourth, our literature review of care aspects sought to establish a comprehensive definition of GP care by using a large set of aspects. However, the selection was based on published articles referenced in English and then adapted to the French context. This approach could potentially limit the scope of our results. To control for this potential effect, we compared our GP care description to that found in the international literature. 16 Overall, our description showed a relatively high level of overlap or external validity. A few items were excluded because users perceived them to be redundant (e.g. patience, compassion, respect, privacy) or they did not feel able to rate their importance (e.g. medical knowledge of the physician).

Conclusion

Our results support a comprehensive approach to GP care and argue in favour of an overall reorganization based on the patient‐centred model. However, GP care reforms can be difficult to implement. To overcome these difficulties, micro‐level initiatives can be adopted. These initiatives are developed from the specific needs of particular groups of patients (e.g. chronic patients; low‐income patients) and aim to improve certain elements of daily medical practice. They have the potential to address, at least in the short term, users’ concerns and to have a positive impact on the health results. 39 This is the case with the ‘Chronic Care Model’ in the United States. In France, one part of the Cancer Plan for 2003–2007 was dedicated to setting up an ‘announcement procedure’. This initiative in patient management addresses users’ concerns. It consisted of several consultations to explain the diagnosis and to discuss the various forms of treatment with the patient, and then, on that basis, to draw up a ‘user‐specific care plan’.

Funding support

This study was funded by the French Institute of Public Health Research (Institut de Recherche en Santé Publique, IRESP).

Conflict of interest

None reported.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all the French experts who agreed to participate. This study was a part of the PROSPERE project (Partenariat pluridisciplinaire de Recherche sur l’Organisation des Soins de Premiers Recours), which includes : Philippe Boisnault, Yann Bourgueil, Didier Duhot, Carine Franc, Philippe Le Fur, Julien Mousques, Michel Naiditch, Aurélie Pierre, Olivier Saint Lary, Philippe Szidon.

References

- 1. Païta M, Weill A. Les personnes en affection de longue duréee au 31 décembre 2007. Points de repère, 2008; 20: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Observatoire National de la Démographie des Professions de Sante (ONDPS) . Annual Report 2006–2007. The General Practice. Paris: ONDPS, 2008; 1: 1–179. [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO . The challenges of a changing world The World Health Report 2008. Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2008: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wendt C, Grimmeisen S, Rothgang H. Convergence or divergence of OECD health care systems? In: International Cooperation in Social Security: How to Cope with Globalisation? Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2005: 15–43. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Quarterly, 2005; 83: 457–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stevenson FA, Cox K, Britten N, Dundar Y. A systematic review of the research on communication between patients and health care professionals about medicines: the consequences for concordance. Health Expectations, 2004; 7: 235–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Safran D. Defining the future of primary care: what can we learn from patients? Annals of Internal Medicine, 2003; 138: 248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lewis J. Patient views on quality care in general practice: literature review. Social Science and Medicine, 1994; 39: 655–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I et al. Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational study. BMJ, 2001; 322: 468–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. A critical review of the Delphi technique as a research methodology for nursing. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 2001; 38: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Okoli C, Pawlowski S. The Delphi method as a reasearch tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manag, 2004; 42: 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mertens A, Cotter K, Foster B et al. Improving health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer: recommendations from a Delphi panel of health policy experts. Health Policy, 2004; 169: 169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bardecki M. Participants’ response to the Delphi Method: an attitudinal perspective. Technol Forecast Soc Change, 1984; 25: 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flocke S, Miller W, Crabtree B. Relationships between physician practice style, patient satisfaction, and attributes of primary care. Journal of Family Practice, 2002; 51: 835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheraghi‐Sohi S, Bower P, Mead N, McDonald R, Whalley D, Roland M. What are the key attributes of primary care for patients? Building a conceptual ‘map’ of patient preferences. Health Expectations, 2006; 9: 275–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Campbell S, Shield T, Rogers A, Gask L. How do stakeholder groups vary in a Delphi technique about primary mental health care and what factors influence their ratings? Qual Saf Health Care, 2004; 13: 428–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hall J, Dornan M. Patient sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of satisfaction with medical care: a meta‐analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 1990; 30: 811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anden A, Andersson S, Rudebeck C. Satisfaction is not all – patients’ perceptions of outcome of general practice consultations, a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract, 2005; 6: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Delgado A, Lopez‐Fernandez LA, Luna JdD, Gil N, Jimenez M, Puga A. Patient expectations are not always the same. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2008; 62: 427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grol R, Wensing M, Mainz J et al. Patients’ priorities with respect to general practice care: an international comparison. Family Practice, 1999; 16: 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ishikawa H, Takayama T, Yamazaki Y, Seki Y, Katsumata N. Physician–patient communication and patient satisfaction in Japanese cancer consultations. Social Science and Medicine, 2002; 55: 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jung H, Wensing M, de Wilt A, Olesen F, Grol R. Comparison of patients’ preferences and evaluations regarding aspects of general practice care. Family Practice, 2000; 17: 236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wensing M, Jung H, Mainz J, Olesen F, Grol R. A systematic review of the literature on patient priorities for general pratice care. Part1: description of the research domain. Social Science and Medicine, 1998; 47: 1573–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haggerty J, Pineault R, Beaulieu M‐D et al. Practice features associated with patient‐reported accessibility, continuity, and coordination of primary health care. Ann Fam Med, 2008; 6: 116–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. WHO . Declaration of Alma‐Ata International Conference on Primary Health Care. 1978. Available at: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf, accessed 23 May 2011.

- 27. Hunter D, Shortt S, Walker P, Godwin M. Family physician views about primary care reform in Ontario: a postal questionnaire. BMC Fam Pract, 2004; 5: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peckham S. What choice implies for primary care. Br J Health Care Manag, 2004; 10: 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peckham S. The changing context of primary care. Public Finan Manag, 2006; 6: 504–538. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Magarey A, Rogers W, Veale B, Weller D, Sibthorpe B. Dynamic Divisions. A Report of the 1997–98 Annual Survey of Divisions. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, National Information Service, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care and the National Information Service . Primary care initiatives: enhanced primary care package. 2010. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/hsdd/primcare/enhancpr/enhancpr.htm, accessed 13 August 2001.

- 32. King HA. Minimum Requirements for Primary Health Care Organisations. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hefford M, Crampton P, Foley J. Reducing health disparities through primary care reform: the New Zealand experiment. Health Policy, 2005; 72: 9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Grumbach K, Selby J, Damberg C et al. Resolving the gatekeeper conundrum: what patients value in primary care and referrals to specialists. JAMA, 1999; 282: 261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ostbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med, 2005; 3: 209–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Scott A, Watson M, Ross S. Eliciting preferences of the community for out of hours care provided by a general practitioners: a stated preference discrete choice experiment. Social Science and Medicine, 2003; 56: 803–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brody D, Miller S, Lerman C, Smith D, Lazaro C, Blum M. The relationship between patients’ satisfaction with their physicians and perceptions about interventions they desired and received. Medical Care, 1989; 27: 1027–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Turner D, Tarrant C, Windridge K et al. Do patients value continuity of care in general practice? An investigation using stated preference discrete choice experiments. J Health Serv Res Policy, 2007; 12: 132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wagner E, Grothaus L, Sandhu N et al. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: a system‐wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care, 2001; 25: 695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]