Abstract

Background Patients’ as well as doctors’ expectations might be key elements for improving the quality of health care; however, previous conceptual and theoretical frameworks related to expectations often overlook such complex and complementary relationship between patients’ and doctors’ expectations. The concept of ‘matched patient–doctor expectations’ is not properly investigated, and there is lack of literature exploring such aspect of the consultation.

Aim The paper presents a preliminary conceptual model for the relationship between patients’ and doctors’ expectations with specific reference to back pain management in primary care.

Methods The methods employed in this study are integrative literature review, examination of previous theoretical frameworks, identification of conceptual issues in existing literature, and synthesis and development of a preliminary pragmatic conceptual framework.

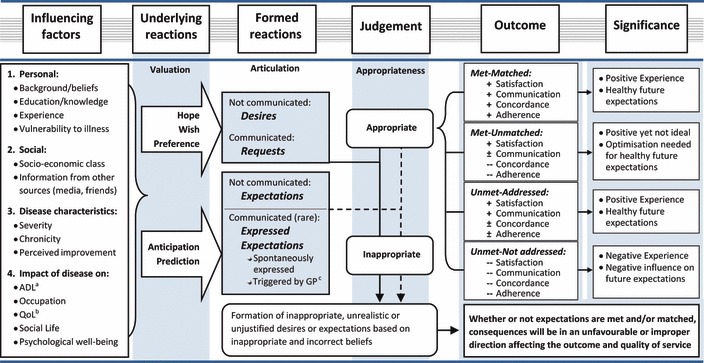

Outcome A simple preliminary model explaining the formation of expectations in relation to specific antecedents and consequences was developed; the model incorporates several stages and filters (influencing factors, underlying reactions, judgement, formed reactions, outcome and significance) to explain the development and anticipated influence of expectations on the consultation outcome.

Conclusion The newly developed model takes into account several important dynamics that might be key elements for more successful back pain consultation in primary care, mainly the importance of matching patients’ and doctors’ expectations as well as the importance of addressing unmet expectations.

Keywords: back pain, expectations, matched, met, theory development

Introduction

The recent National Health Service (NHS) report ‘High Quality Care For All’ highlighted key messages for improving the quality of health‐care services, mainly the importance of considering patients’ opinions when developing care strategies. 1 In the health‐care context, patients’ expectations for care are common 2 and may play a vital role in their concordance with the treatment or advice given, 3 , 4 as well as the overall level of satisfaction with the management. 5 , 6 , 7 Among patients presenting with back pain, condition‐specific expectations for care may include accurate diagnosis, prognostic information, diagnostic testing, prescription of medication or referral, 2 , 8 , 9 , 10 as well as other aspects related to GPs’ understanding, listening and showing interest. 8 , 11 Fulfilment of these expectations has been seen as one important measure of the quality of health‐care systems. 12

There has been an increasing amount of research in this area with an emphasis on the importance of expectations and the potentially important clinical consequences of fulfilling these for a successful consultation in primary care. Patients’ expectations have served as an important predictor of the efficacy of health‐care systems in terms of costs, quality, service utilization and satisfaction. 12 However, research has tended to ignore or undervalue the importance of GPs’ expectations. GPs seem to have their own views and expectations about their role in general practice, as well as patients’ reason for visiting the GP, 13 which might have an important effect on the consultation outcome, 14 as well as GPs’ job satisfaction. 13 Studies investigating the matching of patients’ and GPs’ expectations are lacking. 15 , 16 The effect of patient–GP agreement has been controversial and has not been well established in the literature, 5 mainly because the majority of previous research has looked at the impact of agreement in terms of patient outcomes, for instance, satisfaction and compliance, 3 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 17 , 18 rather than the more important clinical outcomes such as pain severity, disability and functional capacity; nevertheless, most previous research reported that higher discrepancy between patients and health‐care professionals is detrimental to patient care and outcomes. 7 , 19 GPs perceived patients as less co‐operative as a result of low agreement, 20 which would affect the overall consultation, in terms of communication and concordance. Recent evidence reported a significant discordance and mismatch of patients’ and GPs’ shared experience of the back pain consultation in relation to the management approach, treatment expectations and the importance of diagnosis, 21 which highlights the need to address this significant issue.

Back pain care will benefit from research that critically looks at patients’ and GPs’ expectations. 22 From a policy perspective, it is important that patients’ and GPs’ expectations are recognized, understood and optimized in a way to enhance mutual benefit. Fulfilling patients’ appropriate expectations may be a key element for improving the quality of health care; it is suggested, however, that a more potent aspect, which is often overlooked, would be a state of patient–GP matched expectations rather than just a state of met expectations. This might be a powerful influential factor for a more successful back pain consultation in primary care.

In this paper, we propose a preliminary conceptual model, which was developed to address the issues and gaps previously identified in the literature, 15 namely the definitional confusion with regard to expectations, the lack of conceptual framework that can address the interchangeable use of several related terms (e.g. expectations, desires and requests) and the limited attention and interest of the relevant literature in the subject of matched patient–GP expectations. Based on critical analysis of the literature pertaining to expectations, the model was developed to structure the premise of ‘met vs. matched expectations’ and relate it to previous concepts and theories explaining the development and formation of expectations, with the aim of drawing the attention of future research to the important topic of ‘matched expectations’.

Development of the Met‐Matched conceptual model

Procedure

Given the novelty of the topic of ‘matched patient–GP expectations’, and the scarcity of previous research on this aspect, an integrative literature review approach (ILR) was felt to be the method of choice over a systematic review for reviewing the pertinent literature. 23 , 24 The integrative literature review is a structured form of research that involves identification and reviewing of all relevant literature related to a topic of interest (a mature topic or new emerging topic), followed by critical analysis and synthesis of the literature in an integrated way such that new knowledge on the topic is generated. 23 The aim of conducting an ILR was to exhaustively review, examine and critically analyse the existing theoretical literature underlying the formation and development of expectations, as well as models explaining the relationship between patient–GP expectations and its influence on interaction, communication and concordance. This analysis and critical review was then used to develop and synthesize the new conceptual model that integrated the findings of previous literature, while generating new perspectives on the topic. 23

Distinctive steps were followed to provide a coherent structure for the ILR. The process started by conceptual structuring of the review, in terms of identifying the topic, defining the purpose and developing distinctive conceptual and operational definitions of expectations, which would distinguish it from other terms that might have been used interchangeably. 23 , 25 The second step was data collection. To fully explore the construct of expectations in a comprehensive way, a broad range of study designs, including qualitative and quantitative empirical research, as well as theoretical papers were included in the review. A search of all relevant literature related to the range and matching of patients’ and GPs’ expectations was carried out using a number of keywords, including: physician, GP, doctor, patient, expectation, desire, preference, request, agreement, concordance, primary care, general practice and back pain. These keywords were used in different combinations to search MEDLINE, PSYCHINFO, AMED, Science Citation Index, CINAHL and COCHRANE databases for papers published in English from the start of each database until January 2010. All related theories, frameworks and models explaining the development or influence of expectations on various aspects of the health care were also included in the collected data. Detailed results of the ILR can be found elsewhere. 15 The collected data were then reviewed, summarized, evaluated, analysed and criticized in a way to identify strengths and gaps in the current literature. 25 With the literature strengths and deficiencies exposed, the review and critique of existing literature culminated in the new Met‐Matched conceptual model (Fig. 1) that because it posits new relationships and perspectives on the topic yields new knowledge and an agenda for further research. 23

Figure 1.

The ‘Met‐Matched’ conceptual model. aADL: activities of daily living, bQoL: quality of life, cGP: general practitioner, + Positive effect, ‐‐ Negative effect, ± Effect in either direction.

The model is mainly derived from previous empirical and conceptual work related to expectations and represents a synthesis and integration of the existing theoretical literature plus the new perspective of ‘met vs. matched expectations’. The Met‐Matched model is an alternative framework that provides a new way of thinking about the topic of health care expectations and its influence on the consultation and care provision. 23 Clear logic and conceptual reasoning were the cornerstones and the main basis for explanation and justification of the new model. 23 The model is presented with respect to the context of back pain management in primary care. At the heart of this conceptual model lies an appreciation of the potential importance of a state of matched patient–GP expectations rather than a state of met expectations only.

Outcome

Patients’ and GPs’ expectations could be key elements for improving the quality of health care; yet, several barriers interfere with understanding and optimizing these expectations in back pain primary care. 15 Among these are the nature and ways of communicating expectations and the disagreement in the literature about methods to elicit and monitor them. 11 Measures of the quality of health care have recently shifted from satisfaction as a measure of service quality and efficacy to a more robust assessment of the patients’ overall journey and experience within the health‐care system.

One of the early theories that tried to explain expectations is the expectancy‐value theory, which suggested a relationship between beliefs and attitudes. According to this theory, people seem to learn expectations. In other words, each individual forms a set of beliefs that a given response will be followed by some event. These events might have a positive or negative valence that will affect the nature of the formed beliefs or expectations in either ways. 26 They suggested that the formation of beliefs relies on a set of persons’ subjective probability judgements that occur by means of direct observation, inference or from some other external source such as media. 26

Equally, the expectancy disconfirmation theory, another theory that built its foundation on the cognitive attribute of expectations, suggested that the degree of satisfaction is based on a comparison between a set of pre‐formed expectations about the anticipated service quality and the actual service provided. 27 A third model was proposed by Parasuraman, Berry and Zeithaml, 28 which stated that expectations are dual levelled and dynamic. They define two levels of expectations: desired level, which is the service the individual hopes to receive, and the adequate level, which is the level that the individual considers acceptable. In between these two levels lies the zone of tolerance, which can expand and contract according to the context and from one individual to another. 28

Kravitz et al. 12 suggested that each patient comes to the doctors’ clinic with a unique set of perceived vulnerabilities to illness, past experiences and stores of acquired knowledge; such antecedents influence the interpretation of symptoms and lead to the formulation of a set of expectations as well as establish an implicit standard of care. 9 , 12 Patients’ expectations are viewed as beliefs that interact with perceived occurrences to critically appraise the service provided. 29 Patients perceive various events to occur during the consultation; such perceptions are based on actual occurrences that are filtered through the patients’ neurosensory and psychological apparatuses and are compared to expectancies in a way to reach a final evaluation of the service. 29 An important feature of their model is a two‐way interaction between expectations and actual occurrences, where patients’ expectations may modify actual occurrences during the visit via direct requests leading to a different final evaluation of service; similarly, actual occurrences (e.g. doctor explanation or negotiation) can influence expectations. 29

On the other hand, Conway and Willcocks explained how expectations are formed in respect to four key elements 30 : expectations, experience, expectation confirmation and degree of patient satisfaction. A set of factors including personal characteristics, socioeconomic status, previous knowledge and experience, level of perceived pain/risk and information are suggested to influence the formation and shaping of the range of expectations in respect to a specific service and consequently the level of satisfaction.

Based on the ILR of these different conceptual frameworks and models developed to explicate the construct of expectations, the new ‘Met‐Matched’ conceptual model was designed to structure the relationship between different patients’ and GPs’ attitudes occurring during a consultation, the effects on the ensuing experience as a result of responding to these attitudes, and the anticipated influence on future beliefs, attitudes and expectations. The model proposes various levels of analysis of this relationship.

Influencing factors

The Met‐Matched conceptual model is consistent with most previous research that suggests a set of influencing factors play an essential role in the early stages of expectations’ formulation, 9 , 12 , 30 , 31 which is guided by complex and overlapping cognitive and effective processes. 27 This set of influencing factors is believed to be the main underlying foundation upon which all attitudes and reactions are constructed. These antecedents establish the basis of the presenting behaviour based on a range of personal and socioeconomic factors (such as cultural background, beliefs, education, knowledge, experience with health‐care system, vulnerability to illness, socioeconomic class and information from other sources), as well as disease‐related factors (severity, chronicity, impact on social life, psychological well‐being, quality of life and activities of daily living). The range of formed reactions is then judged in the subsequent levels of analysis against three discriminatory refiners: valuation, articulation and appropriateness.

The model integrates new perspectives on expectations with previous theoretical frameworks and models, for example, the value and probability concepts, 29 value and communication model, 32 the expectancy‐value theory 26 and other conceptual frameworks and models, 27 , 28 , 30 , 31 to synthesize the suggested Met‐Matched conceptual model. The model agrees with the distinction, suggested in the literature, between desires and expectations in terms of value and communication, 29 , 32 as well as the previously proposed standardized definitions of desires, expectations and requests. 15 The model suggests the following two stages to influence the development of expectations and desires, in terms of value and articulation.

Underlying reactions (valuation)

Hopes, preferences or wishes reflect an element of valuation, therefore will lead to the formation of requests or desires, which are defined as perceptions of wanting a given element of care. 15 , 33 On the other hand, anticipation and prediction lack this feature of valuation and mainly reflect a plain outlook of what is likely to happen during a consultation, without adding positive or negative appraisal to such expectancy.

Formed reactions (articulation)

The model subsequently differentiates between the formed reactions in terms of articulation; hopes, wishes and preferences that are verbally communicated to the GP are referred to as ‘requests’, while desires are those non‐expressed ones. Similarly, expectations refer to the non‐communicated form of anticipations or predictions, while the term ‘expressed expectations’ denotes those anticipations or predictions that are explicitly articulated to the GP.

Judgement

All formed behaviour is then judged against the critical screen of ‘appropriateness’ in terms of whether its underlying dynamics are based on healthy sound beliefs, assumptions and concepts, as well as its adherence and relevance to available guidelines, standards and clinical evidence. Appropriate reactions will result in healthy justified forms of wants or expectancies, while inappropriate and incorrect beliefs will most probably lead to the formation of inappropriate, unrealistic or unjustified desires or expectations.

Outcome

Moving to a different level of analysis, the model investigates the outcome of the encounter in terms of the response to the formed behaviour. The model defines various forms of the encounter outcome based on the met and matched axes: a met‐matched status refers to the condition when the patient and the GP are thinking alike and the needs of both are met; a met‐unmatched status denotes that the needs of one of the partners are met but there is mismatching of their wants or anticipations; unmet‐addressed reflects the ability of the partners to recognize, acknowledge and respond to unmet wants or anticipations in a proper manner; while unmet‐unaddressed refers to the failure of the partners to respond and react to unmet ones.

The model suggests that higher satisfaction and better communication would be yielded in the met‐matched and unmet‐addressed status, which in most cases would also be associated with a higher degree of concordance and adherence to the treatment or advice given. A met‐unmatched status might result in high satisfaction of one of the partners and possibly a fair degree of communication but it would most probably affect the degree of concordance and adherence to the treatment. On the other hand, satisfaction, communication, concordance and adherence are expected to be at their minimal levels in the unmet‐unaddressed status, where partners fail to communicate effectively, think alike and establish an agreed plan of care.

Significance

The model then interprets these analytical levels to suggest significance of each status in terms of satisfaction, 5 , 6 , 34 adherence to treatment, 3 , 4 communication and concordance, 35 as well as symptom resolution. 7 , 17 , 18 It suggests a positive experience to accompany the met‐matched and unmet‐addressed status; a positive yet imperfect experience is suggested to be associated with the met‐unmatched status with a suggestion of the need for optimization to achieve an ideal relationship between partners, and finally, negative experiences are more likely to be expected in the case of unmet‐unaddressed status.

The model also adopts the idea that the relationship between its different levels is dynamic and closed ended, which means it involves a feedback mechanism; the various resulting forms of expectancies and experiences will eventually shape the initial set of principal influencing factors, 30 with the met‐matched and unmet‐addressed status resulting in healthy future expectations and the unmet‐unaddressed one triggering negative influence on future expectations. This supports the assumption of the dynamic character of expectations, which is well acknowledged in the literature, where the initial expectations of a service might be substantially different from the range of expectations if measured after a service experience. 36

Conversely, the model suggests that all inappropriate desires and expectations that are based on inappropriate or mistaken beliefs would lead to unfavourable or improper consequences in terms of efficacy, quality and overall outcome of the service, whether or not they were met and/or matched. This is in agreement with previous research stating that, whatever the type of treatment, unrealistic expectations may negatively influence patient outcome, may have adverse consequences on both the patient and clinician and may also affect their relationship. 14

The Met‐Matched conceptual model is particularly consistent with that proposed by Janzen et al. 31 which identified several longitudinal phases explaining the development of a health expectation. The proposed Met‐Matched model differs substantially, however, in that it integrates several distinctive aspects that, from a pragmatic viewpoint, would allow the model to be used in empirical research and would allow better understanding of the influence of expectations on attitudes and behaviours presenting in the real world of the medical encounter. These aspects include the appropriateness of the formed reactions (desires or expectations), expression of the formed reactions as well as this unique relationship between the patients’ and GPs’ expectations, in terms of matching of expectations and addressing of unmet ones.

Discussion

The essence of back pain care in general practice is the consultation, which is viewed as a process of patient and GP negotiation, geared towards information, advice or specific care. 15 Patients and GPs appear to have a specific agenda during the consultation, and there seems to be a mismatch between patients’ and GPs’ beliefs with regard to different aspects of the consultation. 13 , 15 Patients’ expectations are mainly related to aspects of information, education, physical examination, GPs’ understanding, listening, showing interest and discussing problems or doubts. 8 , 11 , 37 , 38 , 39

On the other hand, diagnosis seems to come on the top of GPs’ expectations list, 40 along with educating patients and providing information, 41 prescribing effective treatment and avoiding unnecessary tests or referrals. The reviewed literature showed that studies investigating the matching of patients’ and GPs’ expectations are scarce; only two studies were interested in exploring patient–GP agreement or concordance, while others focused on satisfaction or expectations of specific interventions. 15 Unmatched expectations might be attributed to patients’ perception that the GP did not listen to them or did not spend enough time with them, 39 pressures imposed by patients for unjustified or unnecessary services 12 or patients’ doubts about the diagnosis they have been told. 42 GPs’ feelings of frustration were attributed to unmatched GP–patient perceptions, which dramatically affected their ability to apply evidence‐based management of back pain. 43

Examination of the existing literature and critical review of previous theoretical frameworks revealed that aspects of patient–GP agreement or matching are often overlooked or undervalued. In fact, to date, no study has explored the matching of patients’ and GPs’ expectations related to back pain consultation, 12 , 15 , 16 which would hinder full understanding of the dynamics underlying the medical encounter and could deter efforts directed towards improving back pain management in primary care by reinforcing evidence‐based practice. These aspects were sensibly and practically integrated in the proposed pragmatic model, which distinguishes between two different phenomena: met and matched status. While the majority of the previous research emphasized the importance of meeting patients’ expectations for higher satisfaction, better quality of care and more favourable outcome, it failed to capture the wider picture of the patient–GP relationship. The medical encounter structure involves the patient and GP as partners rather than patients as sole recipients of the service; the consultation is actually viewed as a negotiation, two‐way interaction, between the two partners, and it would be improper to look at one aspect and not the other when trying to understand the dynamics occurring during the encounter. Patients’ and GPs’ expectations should equally and concurrently be considered when investigating the quality and outcome of the consultation.

The current model challenges the dominant common assumption that a state of patients’ met expectations would be sufficient for an efficient and successful consultation in favour of looking at the wider perspective of the patient–GP met‐matched framework. Just a state of met expectations simply means looking after the needs of one partner but not the other in a two‐sided relationship, which would influence the underlying dynamics of this relationship. Unlike met expectations, the matching and mutuality of back pain patients’ and GPs’ expectations might be the way forward to improving the quality of back pain consultations in general practice and might provide for the lack of definitive management strategies and could enable GPs to conquer their feelings of frustration when dealing with back pain in general practice.

One of the main pragmatic issues addressed in this model is the appropriateness of the expectations, i.e. how appropriate, justified, necessary or sound a specific intervention is. Several national and international guidelines, systematic reviews and clinical evidence‐based recommendations have been developed to help clinicians establish the most appropriate intervention plans and management strategies based on the best available evidence, while keeping individual patients’ needs in mind. However, adherence to these guidelines and recommendations is still problematic, and barriers to applying such evidence interfere with full implementation of these measures. For example, GPs might still respond to patients’ unjustified expectations to maintain the clinical relationship with the patient 40 or in response to perceived pressure from patients for specific interventions, 44 even if they conflicted with evidence, which would clearly create an unfavourable state of matched patient–GP expectations.

Misunderstanding the ideology, concept and scope of the proposed conceptual model would represent a crucial risk for its failure and would limit its potential implementation. Obviously, it is implied that a state of matched expectations would not always be the optimum outcome unless it is judged against a filter of ‘appropriateness’, i.e. patient–GP agreement about expectations that are justified and based on sound clinical evidence and guidelines. Otherwise, a patient–GP agreement, about having ‘clinically’ unjustified X‐ray investigation (for example), would be as bad as or maybe even worse than having their expectations unmet.

Based on this simple conceptual model, it would be feasible to analyse different presenting behaviour and attitudes observed in primary care consultations. The model is particularly important in addressing a major limitation in previous research in that the expectations’ literature does not distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate expectations. Guidelines and research have shown various expectations as inappropriate or negative; therefore, responding to these negative expectations would be improper. For instance, unmet patients’ expectations of X‐ray investigations would not necessarily mean that the GP has not been successful in responding to patients’ needs. It might simply mean GP’s adherence to evidence and guidelines. Research should be consistent and clear when assessing the range of patients’ unmet expectations, with distinctive discrimination of different types of expectations in terms of their appropriateness. The proposed ‘Met‐Matched’ conceptual model provides a pragmatic structure to differentiate between appropriate justified expectations and unrealistic unjustified ones through the filter of ‘appropriateness’, which would enable better understanding of the range and reasons for patients’ unmet expectations.

The process of developing the model was mainly dominated by a subjective assumption that a state of patient–GP expectations would be in favour of better consultation outcomes. However, this hypothesis is not supported by strong empirical evidence and thus requires further elaboration and exploration to establish the potential importance of matched expectations on the consultation outcome. This preliminary model is intended to set the stage for future research exploring this premise of ‘matched vs. met expectations’. Further studies are required to test this model and its implications on important clinical outcome measures, i.e. pain severity and functional capacity.

Potential applications of the conceptual model

Examples of the potential implementation and practical use of the ‘Met‐Matched’ conceptual model could be inferred from analysing some consultation scenarios drawn from the context of back pain primary care. The therapeutic and clinical contribution of imaging for the diagnosis and evaluation of back pain is known to be minimal, especially if not supported by clinical findings 45 , 46 ; however, based on inappropriate beliefs (owing to any of the principal influencing factors, for example, information from family, knowledge, disease severity), patients might have inappropriate expectations of wanting X‐ray investigation, even though they rarely detect serious pathology and expose the individual to radiation 47 and increased psychological morbidity. 48

Managing these unjustified and improper desires and expectations is another challenge for GPs. 15 Owing to pressure exerted by patients, GPs might make a referral just for the sake of reassurance rather than for justified clinical indication. 49 , 50 , 51 GPs might order some unnecessary or unbeneficial investigations in response to this pressure from patients, 44 , 52 to keep the clinical relationship with patients 40 , 51 or to provide reassurance, 53 even if it conflicted with recommendations, guidelines and standards of care. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that treatment received by back pain patients was often not in line with back pain guidelines, particularly with respect to opioid prescription and X‐ray investigation, 54 thus promoting inappropriate expectations, as GPs themselves will act as a powerful source of patients’ improper anticipations or wants. 12 Conversely, GPs might help shape the range of patients’ expectations and desires, prevent the development of inappropriate ones and refine future ones by: first, avoiding unnecessary and unjustified practice variation and adhering to guidelines and secondly, by attempting to elicit and address patients’ inappropriate expectations, whether by negotiation, explanation or education, which will prevent feelings of dissatisfaction and result in well‐formulated future expectations.

Another example would be a case of patients’ unmet desires and expectations; even with the busy real life of GPs and shorter consultation time, patients would still expect their GPs to listen and spend enough time with them rather than give them a prescription or order some tests to be carried out. Expectations of education and receiving relevant information are highly valued by patients but might not always be met in general practice owing to time constraints. GPs may recognize these desires and expectations and actively respond to address them with alternatives, for example, educational leaflets, Expert Patients Programmes or back classes (unmet‐addressed). In fact, a recent study stated that unmet expectations were satisfactorily explained by GPs with alternatives that were acceptable to patients 94.7% of the time. 55 Conversely, they may fail to identify such expectations and desires, which will subsequently render them unmet, leading to adverse effects on the outcome and satisfaction with care 56 (unmet‐unaddressed). GPs should endeavour to explore patients’ expectations without fear of encouraging patients’ requests for costly tests or referrals that are not indicated, as exploring patient expectations usually led to negotiated discussions that made encounters more successful. 57 In the health‐care context, desires and expectations resemble a Jack‐in‐the‐box, and it is up to GPs to decide whether to leave it closed and ignore it, which could affect the efficacy and outcome of the consultation, or on the other hand, open the box, i.e. explore, acknowledge and address patients’ expectations, and subsequently challenge and help refine unhealthy inappropriate ones, which could positively influence the consultation outcome and help shape better future expectations. A possible way of challenging frustration with the current management strategies and resources available for back pain care is to address and optimize rather than ignore patients’ and GPs’ expectations.

As can be realized from the model, satisfaction, communication, concordance and adherence are suggested to drastically differ by just addressing patients’ unmet desires and expectations; GPs do not have to necessarily meet patients’ expectations to promote better communication and satisfaction; just addressing and negotiating unmet ones can very often promote positive and more favourable experiences. A final example would be an ideal and perfect relationship of met‐matched expectations, where there is a status of patient–GP agreement regarding diagnosis, diagnostic plan and treatment outline leading to a better outcome and higher satisfaction and subsequently a more successful encounter and a high‐quality primary care service for back pain management.

Conclusion

Patients’ as well as GPs’ expectations could be key elements for improving the quality of health care. Previous conceptual and theoretical frameworks, however, failed to appreciate the significance of such a complex relationship and interaction between patients’ and GPs’ expectations. The potential implications of matched expectations are often overlooked and undervalued. The proposed Met‐Matched model suggests that patients’ expectations have to be revealed during the consultation, so that unjustified inappropriate ones are addressed, negotiated and adjusted. It also suggests that taking into account GPs’ expectations and raising the awareness about what patients might expect from the GP and what GPs might anticipate during a consultation would potentially increase the mutual understanding between both partners and could promote more effective communication. Such an optimized state of matched patients’ and GPs’ rational expectations could eventually lead to an idealistic state of concordance, higher satisfaction and less frustration. The main focus and underlying logic of the current paper could be summarized in a single key message proposed by the Met‐Matched model, that is, matching of patients’ and GPs’ expectations and addressing unmet ones could be more significant aspects for a successful consultation than just meeting patients’ expectations. Further research is needed to test the hypothesis of met vs. matched expectations, as well as the practical use of the model in different contexts, and in relation to various outcome measures.

Key message

-

1

Elicit patients’ desires and expectations during the encounter.

-

2

Address unmet desires and expectations with alternatives.

-

3

Manage and negotiate inappropriate desires and expectations.

-

4

Educate patients for well‐formulated future desires and expectations.

-

5

Match rather than just meet patients’ and doctors’ expectations.

Conflicts of interest statement

No Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no intellectual, financial, professional or other personal interest of any nature that may arise from being named as an author on the manuscript, which might appear to affect their ability to present or review data objectively.

Acknowledgement

The study is being funded by the School of Health and Social Care at Bournemouth University.

References

- 1. Darzi AW. High Quality Care For All: NHS Next Stage Review Final Report. London: Department of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. The effect of unmet expectations among adults presenting with physical symptoms. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2001; 134: 889–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maly RC, Leake B, Frank JC, DiMatteo MR, Reuben DB. Implementation of consultative geriatric recommendations: the role of patient & primary care physician concordance. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2002; 50: 1372–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kerse N, Buetow S, Mainous AG, Young G, Coster G, Arroll B. Physician‐patient relationship and medication compliance: a primary care investigation. Annals of Family Medicine, 2004; 2: 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Staiger TO, Jarvik JG, Deyo RA, Martin B, Braddock CH. Patient‐physician agreement as a predictor of outcomes in patients with back pain. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2005; 20: 935–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Azoulay L, Ehrmann‐Feldman D, Truchon M, Rossignol M. Effects of patient and clinician disagreement in occupational low back pain: a pilot study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2005; 27: 817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Starfield B, Wray C, Hess K, Gross R, Birk PS, D’Lugoff BC. The influence of patient‐practitioner agreement on outcome of care. American Journal of Public Health, 1981; 71: 127–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kravitz RL, Cope DW, Bhrany V, Leake B. Internal medicine patients’ expectations for care during office visits. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1994; 9: 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kravitz RL. Measuring patients’ expectations and requests. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2001; 134: 881–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deyo RA, Diehl AK. Patient satisfaction with medical care for low‐back pain. Spine, 1986; 11: 28–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruiz‐Moral R, Perula de Torres LA, Jaramillo‐Martin I. The effect of patients’ met expectations on consultation outcomes. A study with family medicine residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2007; 22: 86–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kravitz RL, Callahan EJ, Paterniti D, Antonius D, Dunham M, Lewis CE. Prevalence and sources of patients’ unmet expectations for care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1996; 125: 730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ogden J, Andrade J, Eisner M et al. To treat? to befriend? to prevent? Patients’ and GPs’ views of the doctor’s role. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 1997; 15: 114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nordin M, Cedraschi C, Skovron ML. Patient‐health care provider relationship in patients with non‐specific low back pain: a review of some problem situations. Baillière’s Clinical Rheumatology, 1998; 12: 75–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Georgy EE, Carr ECJ, Breen AC. Back pain management in primary care: patients’ and doctors’ expectations. Quality in Primary Care, 2009; 17: 405–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hermoni D, Borkan JM, Pasternak S et al. Doctor‐patient concordance and patient initiative during episodes of low back pain. British Journal of General Practice, 2000; 50: 809–810. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bass MJ, Buck C, Turner L, Dickie G, Pratt G, Robinson HC. The physician’s actions and the outcome of illness in family practice. Journal of Family Practice, 1986; 23: 43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cedraschi C, Robert J, Perrin E, Fischer W, Goerg D, Vischer TL. The role of congruence between patient and therapist in chronic low back pain patients. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 1996; 19: 244–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perreault K, Dionne C. Does patient‐physiotherapist agreement influence the outcome of low back pain? A prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2006; 7: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Greer J, Halgin R. Predictors of physician‐patient agreement on symptom etiology in primary care. Psychosomatic Medicine, 2006; 68: 277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Allegretti A, Borkan J, Reis S, Griffiths F. Paired interviews of shared experiences around chronic low back pain: classic mismatch between patients and their doctors. Family Practice, 2010; 27: 676–683. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmq063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schers H, Wensing M, Huijsmans Z, van Tulder M, Grol R. Implementation barriers for general practice guidelines on low back pain a qualitative study. Spine, 2001; 26: E348–E353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Torraco RJ. Writing integrative literature reviews: guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 2005; 4: 356–367. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leung KK, Silvius JL, Pimlott N, Dalziel W, Drummond N. Why health expectations and hopes are different: the development of a conceptual model. Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 347–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Russell CL. An overview of the integrative research review. Progress in Transplantation, 2005; 15: 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison‐Wesley, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thompson AGH, Sunol R. Expectations as determinants of patient satisfaction: concepts, theory and evidence. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 1995; 7: 127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parasuraman A, Berry LL, Zeithaml VA. Understanding customer expectations of service. Sloan Management Review, 1991; 32: 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kravitz RL. Patients’ expectations for medical care: an expanded formulation based on review of the literature. Medical Care Research and Review, 1996; 53: 3–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Conway T, Willcocks S. The role of expectations in the perception of health care quality: developing a conceptual model. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 1997; 10: 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Janzen JA, Silvius J, Jacobs S, Slaughter S, Dalziel W, Drummond N. What is a health expectation? Developing a pragmatic conceptual model from psychological theory. Health Expectations, 2006; 9: 37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Uhlmann RF, Inui TS, Carter WB. Patient requests and expectations: definitions and clinical applications. Medical Care, 1984; 22: 681–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zemencuk JK, Feightner JW, Hayward RA, Skarupski KA, Katz SJ. Patients’ desires and expectations for medical care in primary care clinics. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1998; 13: 273–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fagerberg CR, Kragstrup J, Stovring H, Rasmussen NK. How well do patient and general practitioner agree about the content of consultations? Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 1999; 17: 149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liaw ST, Young D, Farish S. Improving patient‐doctor concordance: an intervention study in general practice. Family Practice, 1996; 13: 427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yuksel A, Yuksel F. The expectancy‐disconfirmation paradigm: a critique. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 2001; 25: 107–131. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sanchez‐Menegay C, Stalder H. Do physicians take into account patients’ expectations? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1994; 9: 404–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Turner JA, LeResche L, Korff MV, Ehrlich K. Back pain in primary care: patient characteristics, content of initial visit, and short‐term outcomes. Spine, 1998; 23: 463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Verbeek J, Sengers MJ, Riemens L, Haafkens J. Patient expectations of treatment for back pain: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Spine, 2004; 29: 2309–2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Parsons S, Harding G, Breen A et al. The influence of patients’ and primary care practitioners’ beliefs and expectations about chronic musculoskeletal pain on the process of care: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Clinical Journal of Pain, 2007; 23: 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tomlin Z, Humphrey C, Rogers S. General practitioners’ perceptions of effective health care. British Medical Journal, 1999; 318: 1532–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Skelton AM, Murphy EA, Murphy RJ, O’Dowd TC. Patients’ views of low back pain and its management in general practice. British Journal of General Practice, 1996; 46: 153–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Breen A, Austin H, Campion‐Smith C, Carr E, Mann E. “You feel so hopeless”: a qualitative study of GP management of acute back pain. European Journal of Pain, 2007; 11: 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Baker R, Lecouturier J, Bond S. Explaining variation in GP referral rates for x‐rays for back pain. Implementation Science, 2006; 1: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Boos N, Hodler J. What help and what confusion can imaging provide? Baillière’s Clinical Rheumatology, 1998; 12: 115–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T et al. European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. European Spine Journal, 2006; 15: s169–s191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Klaber Moffett JA, Newbronner E, Waddell G, Croucher K, Spear S. Public perceptions about low back pain and its management: a gap between expectations and reality? Health Expectations, 2000; 3: 161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kendrick D, Fielding K, Bentley E, Kerslake R, Miller P, Pringle M. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 2001; 322: 400–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Armstrong D, Fry J, Armstrong P. Doctors’ perceptions of pressure from patients for referral. British Medical Journal, 1991; 302: 1186–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Little P, Dorward M, Warner G, Stephens K, Senior J, Moore M. Importance of patient pressure and perceived pressure and perceived medical need for investigations, referral, and prescribing in primary care: nested observational study. BMJ, 2004; 328: 444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Carlsen B, Norheim O. “Saying no is no easy matter” A qualitative study of competing concerns in rationing decisions in general practice. BMC Health Services Research, 2005; 5: 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Keitz SA, Stechuchak KM, Grambow SC, Koropchak CM, Tulsky JA. Behind closed doors: management of patient expectations in primary care practices. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2007; 167: 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Owen JP, Rutt G, Keir MJ et al. Survey of general practitioners’ opinions on the role of radiology in patients with low back pain. British Journal of General Practice, 1990; 40: 98–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Somerville S, Hay E, Lewis M et al. Content and outcome of usual primary care for back pain: a systematic review. British Journal of General Practice, 2008; 58: 790–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Peck BM, Ubel PA, Roter DL et al. Do unmet expectations for specific tests, referrals, and new medications reduce patients’ satisfaction? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2004; 19: 1080–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rao JK, Weinberger M, Kroenke K. Visit‐specific expectations and patient‐centered outcomes: a literature review. Archives of Family Medicine, 2000; 9: 1148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kroenke K. Patient expectations for care: how hidden is the agenda? Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 1998; 73: 191–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]