Abstract

Aim The purpose of this review is to generate an inventory of issues that matter from a patient perspective in health research and quality of care. From these issues, criteria will be elicited to support patient(s) (groups) in their role as advisor or advocate when appraising health research, health policy and quality of health care.

Background Literature shows that patients are beginning to develop their own voice and agenda’s with issues in order to be prepared for the collaboration with professionals. Yet, patient issues have not been investigated systematically. This review addresses what patients find important and help to derive patient criteria for appraising research and quality of care.

Methods/search strategy Information was gathered from Western countries with similar economic, societal and health‐care situations. We searched (from January 2000 to March 2010) for primary sources, secondary sources and tertiary sources; non‐scientific publications were also included.

Results The international inventory of issues that were defined by patients is covering a large array of domains. In total, 35 issue clusters further referred to as criteria were found ranging from dignity to cost effectiveness and family involvement. Issues from a patient perspective reveal patient values and appear to be adding to professional issues.

Conclusions Patient issues cover a broad domain, including fundamental values, quality of life, quality of care and personal development. Quite a few issues do not find its reflection in the scientific literature in spite of their clear and obvious appearance from tertiary sources. This may indicate a gap between the scientific research community and patient networks.

Keywords: decision making, patient criteria, patient empowerment, patient involvement, patient rights

Introduction

In most Western countries, patient participation is increasingly acknowledged and accepted. Patients are involved in health‐care services, 1 health‐care quality, such as the development of guidelines, 2 , 3 and health‐care research, such as agenda setting 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 or in studies concerning juridical and ethical aspects of the position of patients in research. 9 The level of participation differs according to the context and can be assessed by the ‘participation ladder’ model. 8 , 10 In this review, we refer to ‘patient groups’, indicating the patient collective rather than individual patients. Patient representatives, patient organizations or patient advocates are all acting on behalf of a ‘patient group’.

Although the aim of participation is to make patient organizations an equal party in health‐care decision making, this goal is not reached in practice. 11 There is a lack of formal knowledge among patients when negotiating with well‐trained professionals. Other limitations relate to politicized and asymmetrical contexts where it is difficult for patients to become an equal partner in morally sensitive and strategic issues. 8 Empowerment of patient groups and consumers is therefore a recurring issue in the literature on patient involvement. Nierse and Abma 12 show that ‘enclave deliberation’ among groups with converging interests is a necessary step towards development of a political voice, especially when it concerns vulnerable groups. A process of appreciation and raising awareness is required to develop a shared agenda, and only thereafter, negotiations with professionals are feasible. 13 Oliver et al. 14 concluded that successful involvement requires appropriate skills, resources and time and provides consumers with information, resources and support to empower them in key roles for consulting their peers and prioritizing topics.

In attempts to answer the question how the dialogue between patients, researchers and health‐care professionals can be improved, quite a few studies focused primarily on the methodology and process: they describe what conditions are required and how these can be created. 3 , 5 , 13 , 15 In a systematic review that investigates best ways of involving consumers in health‐care decisions at population level, Nilsen 16 distinguishes two basic forms of generating patient issues. Patient issues can be achieved either through consultations or through collaborative processes. Consultations can be single events, or repeated events, either on a large or on a small scale. 16 Consultation happens on an individual or group level to stimulate a dialogue. The dialogue model for research agenda setting developed by Abma and Broerse, 8 which is based on interactive policy models and responsive evaluation, combines consultation and collaboration.

The purpose of this review is an inventory of issues that matter to patients before they start negotiating with professionals about health‐care research and quality of care. Its added value lies in the fairly wide international coverage and in the comprehensive number of key issues it identifies, compared to specific studies. This review also aims to contribute to the political power of patients but concentrates mainly on issues of content in an attempt to make an inventory of the issues patients bring forward when negotiating with professionals about health research and quality of care. The review intends to derive a set of patient issues that reveal the patient perspective and can be used to develop ‘criteria’ for appraisal of health research and quality of care activities and policy. Patients experience specific challenges when participating in these processes, because there is no appraisal tool from a patient perspective. At the same time, the number of scientific studies and non‐scientific projects wherein patients raise their issues increases gradually. From these studies and projects, issues can be identified that were raised by patient and patient representatives when they responded to health research, quality of care activities and policy. We assume that in general, these issues differ from the issues raised by health‐care professionals and researchers as patient issues originate from life world experiences and experiences are colouring one’s world view and values. 3 , 12

Method

This inventory and synthesis of data started from a focused and selective review of scientific literature using guidance provided by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 17 Soon, however, it became clear that issues from a patients perspective are not only mentioned in scientific literature but more so in a variety of other information sources. 18 Therefore, the authors agreed to conduct a data synthesis as described by the Joanna Briggs Institute. 19 A data synthesis has the aim to assemble conclusions, to categorize these into groups on the basis of similarity in meaning and next to aggregate these to generate a set of statements that represent the aggregation. 19 The issues found are extracted as full text parts, tabulated and finally clustered to descriptive themes, in this study referred to as ‘clusters of issues’, based on similarity of meaning.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

In this review, inclusion criteria are used to focus on patient issues in state‐of‐the‐art health‐care systems in Western countries with a similar socio‐economic situation and health‐care level. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are set on population, language, geographical area, quality of information sources, keywords and search strategy. The inventory and synthesis uses English and Dutch language sources only.

In this review, people can have multiple roles, such as advocate, adviser or provider of information. In this review, we focus on patients as advisor or advocate. They may also be health‐care consumers. In our point of view, patients, as advocates, speak on behalf of the ‘patient group’ and their organization. The patient organizations have collected data about issues, claims and concerns in an early stage from individual patients/users within the health‐care system. Professionals are excluded.

Integration of primary, secondary and tertiary sources

We focus on empirical scientific studies with a method section (primary sources) and other highly relevant scientific studies or articles, either with or without a method section (secondary sources). The limited quantity of available primary and secondary sources necessitates the use of a tertiary source group: non‐scientific publications, reports and patient information databases. The authors assumed that this indicates that patient group issues might not be sufficiently explored on a scientific basis. Hence, we included these three types of sources because of their special interest for the main research question and aim of the study. Tertiary sources, originated by patient groups, are assumed to reflect genuine patient issues rather than issues attributed to them by, e.g. social scientists. This further defines the special character of this study: the integration between primary, secondary and tertiary sources.

Search terms

The search strings we use consist of terms being used to describe the role of patients when it comes to their involvement in quality of care and health research. Where in some countries the term ‘participation’ is being used either for ‘right to say’ or for ‘taking part in society’ as opposed to social exclusion, the European and North American literature uses ‘empowerment’ and ‘involvement’ in relation to ‘patient rights’ and ‘decision making’.

Our central search string is: patient involvement. Terms used in conjunction are the following: public, patient advisors, expert patient, patient participation, criteria, peer reviewers, client councils, research clinic guidelines and agenda setting. Furthermore, the –currently fashionable– terms: patient rights, patient advisor, patient empowerment and patient centeredness are used to verify completeness of the search.

The search strategy to locate primary, secondary and tertiary information sources comprises use of the electronic databases Cochrane Library, Pubmed (Medline), Cinahl, Dipex, Patient and Public Involvement Programme (PPIP) and James Lind Alliance sources. Furthermore, the search includes patient organization information exclusively published on the internet and reference list tracking on author, conducted by keywords or by implied content. The search is conducted in information published within the time period between 2000 and March 2010. Patient groups were critical about their influence in research and health care and wrote about this also before this time period. Literature search further back in time would distort the image of ‘current’ patient issues however. The search was therefore limited this time period.

The identification of relevant articles and publications took several steps. The first database search in PubMed and Cochrane Library on our central search string (patient involvement) on the complete text of articles provided us with more than 6000 hits in PubMed and >1000 in Cochrane. When we limited our string to ‘public patient involvement’, it resulted in less hits (e.g. about 650 hits in PubMed). Searches in conjunction with other terms mentioned above (e.g. patients advisor) provided us with less hits of which a selection has been made via screening of titles, abstracts and keywords, a screening of a selection of full texts. Some 301 articles were found by database search and a further 48 by reference tracking and internet search, resulting in 349 sources in total. No comparable synthesis was found in the Cochrane Library.

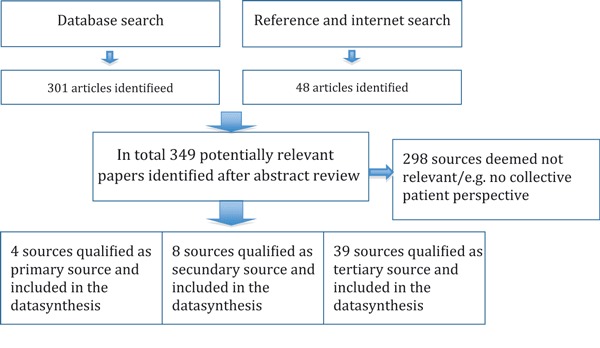

After a check of the quality of the research methods, duplicates and articles without a method section were eliminated as a primary source. We decided to eliminate articles that were not providing information from a collective patient perspective but, for example, from a professional point of view. The sources were then allocated to one of three categories: primary – empirical studies having a method section; secondary – other highly relevant scientific studies; and tertiary – reports and publications that originate from patient organizations and governmental institutions. Two sources originated outside the time interval, but we included them for special interest: Herxheimer 9 and Lithuania. 20 Next, we included a publication of the WHO. 21 This source indicates that emphasis is primarily concentrated on development of tools for advocacy such as ‘position statements’, ‘fact sheets’ and ‘example letters’. These tools enable patients or citizens to discuss disease‐specific health‐related matters in lay language with those in charge and professionally involved (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart indicating the results of the search and data synthesis.

Results

Of the 349 sources identified, some 296 sources were deemed not relevant to this study as they have no bearing on collective issues of patients. The selected 53 sources do contain a variety of information on issues that matter and their context from a collective patient perspective. Below, we review relevant sources, we summarize the extracted issues from these sources and we analyse them in depth. Primary sources, which qualify as empirical studies with a method section are as follows: Herxheimer et al. 22 on quality of care and Herxheimer 9 and Nierse and Abma, 12 both on research. Two studies are relevant for contextual purposes: Broerse et al. 2 and Nilsen. 16

Secondary sources identified are as follows: Bal and Van de Lindeloof 23 on both health research and quality of care, Grit et al. 24 Lindert et al. 25 Uiters et al. 26 HFE, 27 Van Santvoort, 1 and Schalock and Alonso, 28 all on quality of care and finally Stewart and Oliver 4 on health research.

The search further resulted in 39 tertiary information sources originating from patient organizations, government institutions and private organizations.

Tertiary sources on both the quality of care and the research domain issues are WHO‐a, 29 AF 30 and EPF‐a. 31

Tertiary sources on quality of care are the following: PA, 32 Patient UK, 33 WHO‐b, 34 WHO‐c, 35 Lithuania, 20 Sandor, 36 Belgium, 37 Brazinov et al. 38 Deutschland, 39 Wiederholt et al. 40 HSF, 41 Al‐Anon, 42 CDA, 43 Catsad, 44 ALA, 45 NIA, 46 ALF, 47 IAPO, 48 EPF‐b, 49 EPF‐c, 50 EPECS, 51 EIWH, 52 Picker Institute, 53 Planetree 54 and Shaller. 55

Tertiary sources on research are CC, 56 WHO‐d, 57 Kelson, 58 IAPO, 59 Involve 60 and JLA. 61

Other tertiary sources are relevant to this study although they are not providing issues from a patient perspective: Vilans, 62 WHO‐e, 21 LHSC, 63 PatientView 64 and Hjertqvist. 65

Quality of care

Herxheimer et al. 22 introduce a database of UK patients experiences called The Database of Personal Experiences of Health and Illness (DIPEx). One of its purposes is to identify ‘questions that matter’ for people who are ill and their families when dealing with investigations, prognosis, lifestyle and treatment choices. Four main issues are identified: (i) finding information when confronted with a new diagnosis or choice, (ii) how to discuss difficult subjects related to a disease, (iii) positive experience stories at times when negative stories are highlighted by the media, and (iv) stories reinforcing solidarity with others.

Bal and Van de Lindeloof 23 analyse the policy‐making process around the allocation of limited health‐care system budgets in different countries: USA, Canada, Sweden, UK, New Zealand and Israel. They mention patient criteria being used in Oregon (USA) and report the use of a set of 13 criteria from patient perspective. Among these were ‘quality of life’, ‘prevention’ and ‘cost effectiveness’. According to their study, Canada shows a variety of ‘patient involvement’ methods between provinces. Sweden organized a discussion in society around three ethical principles and their priority that became part of the current law: (i) ‘Human dignity’, (ii) ‘Need for care and solidarity’ and (iii) ‘Cost effectiveness’. In the UK scientific and social value, judgments on policy have separate paths. Social judgments, based on ‘standards, values and preferences prevalent in society’, come from an –ideally– representative Citizens Council. Both types of judgments are used by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) to evaluate healthcare, guidelines and research. Next, Bal and Van de Lindeloof describe that in New Zealand, the National Advisory Committee on Health and Disability (NHC) uses questionnaires in an evaluation by stakeholders in the report or proposal submission process and health‐care priority trade‐off studies. Four criteria are being used: ‘efficacy’, ‘efficiency’, ‘fair distribution’ and ‘consistency with social values’. In the Health Parliament in Israel, citizens deliberate on ‘ethical and cost issues’ related to health‐care services.

Grit et al. 24 stipulate the specific needs of foreign patients using health‐care systems in two countries. Lindert et al. 25 investigate the needs of the four biggest non‐indigenous groups in the Netherlands resulting in some fifty important issues. This list contains many issues that would normally be considered equally relevant by any patient. However, for this study, it provides three points of specific interest for the foreign patients group: first, the complexity of also ‘receiving treatment and prescription drugs in another country’; secondly, the need for ‘medical information in another language’, both verbally and in writing; and thirdly, there are ‘cultural issues, e.g. a preference for a female doctor’. Differences between countries and health‐care systems result in differences in issues that patients value of importance. Teunissen and Abma 18 point out that immigrants are using both the Dutch health‐care system and systems in other countries. Uiters et al. 26 identify ‘compliance with prescribed medication in the Moroccan and Turkish ethnic groups [in the Netherlands] as non‐optimal’. From this, we elicit the issue: intercultural sensitivity.

The private and public supported publishers of PatientView 64 present 172 entries in their European Patient Groups directory ‘with an interest in some element of health advocacy’. Three organizations were found to list issues relevant to this study in their publications: HFE, 27 EPECS 33 and EIWH. 52 These mention a wide variety of issues, dealing with information, quality, self‐care and intercultural sensitivity problems.

Van Santvoort 1 investigates the relation between policy and disability in nine European countries and how this translates into participation in society and subjective well‐being. Key policy issues for people with a disability are ‘coherence in legislation and adequate budget’ for implementation of countermeasures. A risk is also identified: new ‘fragmentation owing to increased autonomy’ of the local communities in adopting their own policy on execution of health‐care activities.

Schalock and Alonso 28 describe the individual perception of quality of life. Their inventory of different ways to express, measure and describe quality of life in English‐speaking countries highlights commonly felt aspects such as ‘well‐being, social inclusion, freedom of choice, positive self‐image, future perspective, opportunities for self‐expression’. Their model is being used in the Netherlands among Disabled Care Institutions according to Vilans.nl. 62 The Schalock and Alonso 28 model mentions aspects in relation to quality of life: ‘happiness, lifestyle, physical, psychological and social impairment, living conditions in institutions, family contacts’.

Hjertqvist 65 provides a series of source document references on European country level when it comes to ‘patient empowerment’. Lithuania, Hungary, Belgium, Estonia, Poland, Slovakia, Germany and the Netherlands were further investigated because these show the highest rankings in the EPEI (European Patients Empowerment Index). The wide variety of issues found comprises e.g. access, choice, information, consent, complaint, medical file, privacy and damage compensation.

The patient support group platform Health First Europe, HFE, 27 conducted a survey on healthcare and patient policy priorities. The response of 77 opinions of decision makers and stakeholders in the Brussels EU policy‐making periphery, among which patient representatives as well, shows widely advocated and an increasingly felt importance of: ‘new technology and methods, efficiency, healthy lifestyle, self‐monitoring for chronic conditions and preventive screening’. Further search resulted in various issues of importance from a patient perspective, concerning quality of life, prevention, human dignity, the need for care and solidarity, cost effectiveness/efficiency, efficacy, fair distribution, consistency with social values, new technology and methods, healthy lifestyle, self‐monitoring for chronic conditions and preventive screening. 20 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40

The Canadian Association of Genetic Counsellors compiled a directory of support groups on a wide variety of – in some cases rare – genetic diseases. The London Health Sciences Centre LHSC 63 publishes this directory on the internet. The wide variety of diseases, each organized in separate patient groups, did not result in a common set of patient perspective issues. To explore patient issue diversity, we decided to further investigate four groups: heart diseases, alcoholism, diabetes and the rare neurodegenerative genetic disease Tay–Sachs. A large number of issues were found in HSF, 41 Al‐Anon, 42 CDA 43 and Catsad, 44 varying from privacy and information needs to access and information requirements to the health‐care institutions.

Voice4Patients.com 66 presents on the internet links within the USA to some 75 disease‐specific patient support groups. To identify the commonality of issues shared between large patient groups, the internet information of four groups known to represent diseases with large number of patients were explored. Publications covering arthritis, lung, Alzheimer and liver diseases were searched. The main issues, found in AF, 30 ALA, 45 NIA 46 and ALF, 47 are related to safety, lifestyle and the health system.

WHO‐a, 29 IAPO, 48 EPF‐b, 49 EPF‐c, 50 Picker, 53 Planetree 54 and Shaller 55 provide a wide variety of issues from patients in health‐care institutions. Most frequently mentioned issues relate to information and to contacts with family and friends.

Health research

Herxheimer 9 lists the six rights of patients in clinical research as used in the Primary health‐care department at the University of Oxford, UK: (i) ‘Know what his/her rights are, (ii) The right to adequate information, (iii) The right not to be worried or hurt by information, (iv) The right to withdraw from trial, (v) The right on confidentiality, (vi) Post‐study results should be communicated to patient or next of kin’. These can be translated into the following issues: information, choice, ethics and privacy.

Nierse et al. 67 conducted a research project where patients and their organization engaged in a dialogue with researchers about an agenda for scientific research. In this study, patients ‘asked attention for the daily, short term problems outside the medical realm’ (ibid). In another study, Nierse and Abma 12 ranked discrimination and friendship as top priorities for research.

Bal and Van de Lindeloof 23 address both quality of care and health research. Main issues are related to cost, ethics, values and the health system.

Stewart and Oliver 4 conducted a literature survey, on behalf of James Lind Alliance JLA, to assess patient experience input in setting research priorities. This literature survey resulted in patients contributing in various ways in 43 of the 258 Cochrane library studies explored. This group of studies addressed ‘services’, ‘interventions’ and ‘health conditions’ as issues of importance.

Further search in WHO‐a, 29 AF, 30 EPF‐a, 31 CC, 56 WHO‐d, 57 Kelson, 58 IAPO, 59 Involve 60 and JLA 61 resulted in a wide variety of issues relating to empowerment, effectiveness, safety and relevance (Table 1a,b).

Table 1.

(a) CCIs in the quality of care domain. (b) Issues in the research domain (see numbers in references list)

| Cluster | Primary and secondary sources Q | Tertiary sources Q |

|---|---|---|

| (a) | ||

| Access | 43, 51, 20, 48, 53, 40 | |

| Age | 35, 52 | |

| Alternatives | ||

| Buildings | 28 | 41, 55, 40, 54 |

| Choice | 28 | 20, 36, 37, 38, 39, 48, 54 |

| Communication | 35, 38, 31 | |

| Compensation | 20, 39 | |

| Complaints | 32, 20, 36, 37, 38 | |

| Consent | 20, 37, 38, 50 | |

| Cost | 23, 27 | 50, 31, 33 |

| Cross‐border | 24, 25, 26 | 29, 51, 48, 53 |

| Dignity | 23 | 36, 37, 50, 31, 40 |

| Disability | 28 | 35, 49, 50, 31 |

| Diversity | 24, 25 | 35, 45, 49, 31 |

| Education | 35, 44, 40 | |

| Effectiveness | 23 | 50 |

| Empowerment | 23 | 34, 35, 43, 32, 38, 50, 31, 48 |

| Ethics | 23 | 38, 50 |

| Family, friends | 28 | 44, 47, 36, 50, 48, 53, 40, 54 |

| Fear | 48, 53 | |

| Gender | 35, 52, 49 | |

| Health system | 23, 1 | 41, 30, 46, 47, 20, 36, 38, 48, 40, 54, 33 |

| Information | 24, 22, 25 | 29, 43, 44, 46, 32, 52, 20, 36, 37, 38, 39, 50, 31, 48, 53, 54 |

| Lifestyle | 23, 27 | 35, 43, 41, 30, 46, 33 |

| Medical file | 32, 20, 36, 37, 39, 50 | |

| Method | 27 | 29, 41, 54 |

| Pain | 30, 32, 37 | |

| Privacy | 35, 42, 20, 36, 37, 39, 50, 55 | |

| Quality | 43, 51, 37, 38, 39 | |

| Quality of life | 23 | 36, 53, 55, 40, 54 |

| Relevance | ||

| Safety | 30, 46, 47, 50 | |

| Self‐care | 27 | 52, 5 |

| Social security | 28 | 50, 40 |

| Values | 23 | 48, 53 |

| Cluster | Primary and secondary sources R | Tertiary sources R |

|---|---|---|

| (b) | ||

| Access | ||

| Age | ||

| Alternatives | 56 | |

| Buildings | ||

| Choice | 9 | |

| Communication | 31, 59 | |

| Compensation | ||

| Complaints | 31 | |

| Consent | 31, 58 | |

| Cost | 23 | 29, 31, 59, 60 |

| Cross‐border | ||

| Dignity | ||

| Disability | ||

| Diversity | 57, 56 | |

| Education | ||

| Effectiveness | 23, 4 | 31, 59, 56, 61, 60 |

| Empowerment | 9 | 57, 59, 56, 58, 61, 60 |

| Ethics | 23 | 31, 6 |

| Family, friends | ||

| Fear | ||

| Gender | ||

| Health system | 23 | |

| Information | 9 | 31, 58 |

| Lifestyle | 12 | |

| Medical file | 9 | 31 |

| Method | 30, 31, 56, 60 | |

| Pain | ||

| Privacy | ||

| Quality | 4 | 31, 6 |

| Quality of life | ||

| Relevance | 30, 59, 56, 60 | |

| Safety | 9 | 57, 31, 59, 60 |

| Self‐care | ||

| Social security | 31 | |

| Values | 23 | |

Critical analysis

The objective of this study is to identify the international usage of collective patient issues in order to develop criteria for appraisal. The 357 extracted issue texts found in the search were tabulated and –based on the available information from the various primary, secondary and tertiary sources– assigned to either the quality of care (Q) or research (R) domain. In seven exceptional cases, an extracted issue text had to be allocated to both domains on a fifty‐to‐fifty percentage basis. Each of the 357 issues was subsequently allocated to a geographical area and to a specific disease, as applicable, both based on the contents of the source document. This study looks for non‐specific patient criteria applicable to a wide variety of diseases and a large geographical area. For each issue related to a single country (or a smaller geographical area) or related to a single disease/impairment (rather than multiple diseases or impairments), markers for verification purpose were set.

The first observation is that many of the 357 issues are almost identical in their linguistic meaning or show significant overlap. This calls for clustering in order to find key issues. These key issues are the starting point for defining patient ‘criteria’ in the future of our research. The clustering process begins with the first issue text extract. Any overlapping other issue texts are searched for and a common denominator is defined. This results in the first cluster. All other issue texts are processed in a similar manner until all texts have been allocated to a cluster and all clusters together constitute an envelope around the content of all issue texts, being defined by detailed cluster descriptions. Accordingly, each of the 357 issue texts was assigned to one of in total 35 clusters based on equality, similarity and linguistic best match. Then, the total frequency of occurrence per cluster was counted by simply adding up the number of extracted texts allocated to each individual cluster. These clusters are presented in Table 2 (Fig. 1). The descriptions provide detail on cluster attributes found in the extracted issues.

Table 2.

Patient criteria found in international literature

| Nr | Criteria | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Information | Information about disease, medicines, treatment, positive and negative experiences, difficulties and project results in simple, jargon free, own language |

| 2 | Health system | Health system provides medical advice when needed, a suitable range of therapies, coordinated, integrated and continuous care, assigns adequate means and enough professional care providing staff, arranges transport, nutrition and prevention activities. |

| 3 | Empowerment | Patients are involved and/or represented in health‐care policy, quality and research and have a say in how the providers and health authorities are held accountable. The patients voice differs from professionals’ voice. Patients have an independent and equal say in priority setting and appraisal. |

| 4 | Safety | Approved, tested, appropriate, hygienic and safe methods, medication and equipment are used while providing care and/or conducting clinical trials. Risks are identified and explained. Continuous and responsible care and follow‐up are provided. Availability of experimental drugs after trial is known. |

| 5 | Lifestyle | The patients lifestyle, weight control, physical exercise and addiction aspects are taken into account |

| 6 | Choice | Patients choose doctor, nurse, treatment and institution. Patients may withdraw from treatment or trial, leave an institution and have self‐determination up to the end of their life. |

| 7 | Effectiveness | Medical intervention outcomes for patients are positive, effective, are beneficial to – or an improvement in– the patient groups health and well‐being as experienced in daily life and are well balanced against negative effects. Equity. |

| 8 | Quality of life | Quality of life experienced while staying in health‐care institutions is ensured by comfort, human contacts, nutritional and nurturing food, opportunities for self‐expression, arts, culture and entertainment, spirituality and religious services and enhancing each individuals life journey. |

| 9 | Method | The best methods, technologies, therapies and techniques are used. Innovation, early diagnosis and prevention are of prime importance. Researchers are skilled and experienced, use the best international evidence to conduct trials. Peer review of experiment design. |

| 10 | Cost | Cost is in balance with the value of the outcome. Patients are informed about funding, about cost for their participation, about financial support and about cost reimbursement. Duplication of resources is avoided. |

| 11 | Disability | Disabilities of patients are taken into account in health care provided. This includes disfigurement, reduced performance, requiring assistance, physical fitness, health condition, the severity of impairment either physical or psychological. Mental/intellectual capacity and transportation needs. |

| 12 | Medical file | Medical records are confidential, secure, accurate and accessible for patients |

| 13 | Quality | Recognized and respected organizations. The quality of treatment, supporting evidence and research, medication, supplies, (palliative) care and services is high. |

| 14 | Diversity | Diversity among patients is taken into account. This includes social background, social/cultural differences, ethnic groups, marginalized groups, profession and social skills. |

| 15 | Relevance | The relevance for the patient group, the general public and for health improvement is taken into account. This includes priority for juvenile incidence, critical review of planned research purpose and verification against policy and practice experience. |

| 16 | Cross‐border | Patients receive health care, medication and treatment across country borders and health‐care organization borders in a continuous, coordinated and integrated way. |

| 17 | Family, friends | Patients are enabled to get all the support of family and friends they need during their stay in health‐care institutions. Family, friends and carers may have a different perspective from that of patients. |

| 18 | Privacy | Patients get the privacy they need. This includes taking into account that they may be HIV positive, are ex mental illness patient or require anonymity. |

| 19 | Access | Patients have access to the best possible health care and support |

| 20 | Buildings | The built environment in health‐care institutions employs the best architectural and interior design to ensure optimum living conditions. |

| 21 | Complaints | Patient complaints are handled in a correct way. A knowledgeable contact person is appointed. |

| 22 | Dignity | Respect, personal integrity and dignity support a positive self‐image, avoiding stigma. |

| 23 | Values | Health care is consistent with standards, values and preferences prevalent in society. Patients needs, autonomy and independence are respected. |

| 24 | Consent | Patients give informed consent prior to any medical intervention, treatment and clinical trial. |

| 25 | Ethics | Professional performance and conduct comply with ethical standards, fairness and justice. |

| 26 | Communication | There is adequate communication between patients, care providers and other stakeholders. Bureaucracy is avoided. |

| 27 | Education | Education of patients/clients is taken into account. |

| 28 | Pain | Patients get treatment that avoids, reduces and manages pain. |

| 29 | Self‐care | Patients get support to self‐monitor and self‐manage their chronic disease |

| 30 | Social security | Patients are protected against social exclusion and discrimination. This includes insurance coverage, work, social support network and social security provisions. |

| 31 | Age | Health care takes into account the age of patients. |

| 32 | Compensation | Patients are compensated for damage inflicted by healthcare or health research institutions. |

| 33 | Fear | Patients get emotional support and treatment that avoids, alleviates and manages fear and anxiety. |

| 34 | Gender | Health care takes into account gender aspects. |

| 35 | Alternatives | Health care and health research take into account possible alternative interventions |

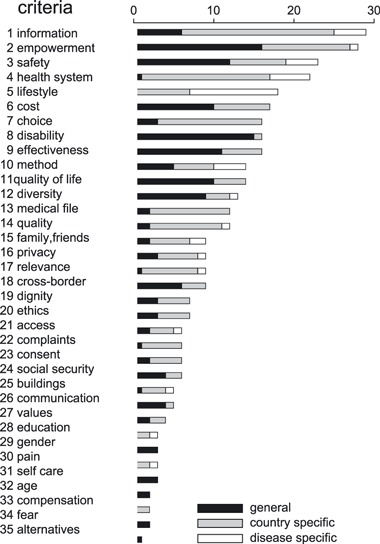

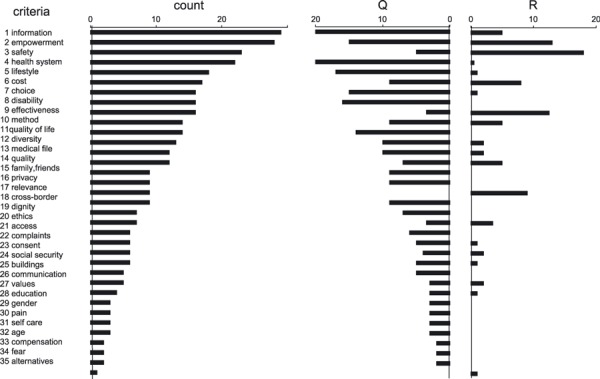

The second observation is that a significant part of the clusters is not unique to a single domain. Figure 2 shows the clusters, listed in count frequency ranking order, distributed over the domains quality of care (Q) and research (R). This demonstrates that 18 of the 35 clusters are associated with both Q and R domains. These are empowerment, information, safety, health system, cost, choice, effectiveness, method, diversity, medical file, quality, ethics, complaints, consent, social security, communication, lifestyle and values. The Q domain contains 33 of the 35 clusters. The R domain contains 20 of the 35 clusters, so in total 15 clusters are not found to be associated with R. In contrast, only two clusters are unique to the R domain: relevance and alternatives.

Figure 2.

Criteria and their non‐specificity for disease and country.

The third observation concerns the insensitivity of this analysis for disease‐ and geographical area–specific issues. The 357 issues are found to be 73.7% quality of care‐oriented and 26.3% research‐oriented. Of 357 issues analysed, 39 are disease specific. In total, 180 of the 357 issues are originating from various single countries. This raises the question whether clusters have common ground for use by a wide variety of patient groups. When two or more single disease–originated issues support a cluster, the cluster itself is not disease specific. The same applies to single country–originated issues. All 35 clusters pass these two checks. Addition of any further single disease– or single country–originated issue to the 357 issues would not be likely to necessitate addition of a new cluster to the 35 clusters. This implies data saturation within the search limitations set for this review. Figure 3 illustrates the clusters non‐specificity for single disease/impairment and single country.

Figure 3.

Criteria frequencies and their applicability to the domains Q‐Quality and R‐Research.

The fourth observation is an underrepresentation of key issues in the primary and secondary sources. There is a striking lack of presence of high frequency Q and R key issues in the scientific sources information. The clusters: empowerment, safety, lifestyle and choice are found in relatively small proportion compared to their presence in tertiary information sources. Some 13 clusters are not found in scientific sources, in spite of their clear and obvious appearance from tertiary sources. These are privacy, relevance, access, complaints, consent, communication, education, gender, pain, age, compensation, fear and alternatives. This may indicate a gap in, or rather a lack of presence of, scientific research activity in a significant part of the field of patient involvement.

The fifth observation is that a substantial number of key issues extend beyond the biomedical realm of health research and health‐care institutions. Some eight of the 35 clusters identified in this study qualify as mostly society‐ or well‐being‐oriented issues. These are quality of life, family/friends, lifestyle, diversity, fear, dignity, self‐care and social security. The other 27 clusters deal with the relevance of treatment or research, the role and right to say of patients and ethics/safety issues.

Discussion

This study has some limitations. It focusses solely on Western, mostly English and Dutch language countries. Further research on this could amend our results.

This is not a conventional systematic review, as mentioned in the methods paragraph, but focuses on secondary and tertiary sources as well. We include secondary and tertiary sources in order to study experiential knowledge on patient issues. Without the use of experiential knowledge, found predominantly in secondary and tertiary sources, we would not have been able to elicit the issues as described.

Thus, what could explain this underrepresentation gap between issues found in primary and secondary scientific sources and tertiary sources? First, patient groups appear to be fighting predominantly on an issue level for better health care and research performance. Patient groups often use fact sheets and standard letters to equip their representatives and advocates for negotiations. Although many issues can be derived from the sources found, patient organizations have not synthesized these and translated them into, e.g. a systematic appraisal method or preset levels of acceptance per issue. This may explain why only some relevant information was found in primary sources.

Secondly, agenda of patients are often characterized by a broad range of subjects whereas agenda of professionals are more focused on specific areas. Researchers tend to focus primarily on physical functioning and medical issues like effectiveness of medical interventions or improving diagnostic possibilities. Patients, however, mention a plethora of issues, including daily, also work‐related problems, quality of life, emotions (fear and anxiety) and issues concerning the relationship with health‐care professionals. 12

This attention for a broad context on patient issues relates with a need for a more integrated perspective on health and illness and an integral vision of how health care should be organized. This perspective includes more existential issues as well as psychological, social, spiritual and cultural issues when looking at well‐being in addition to illness. 68 , 69 From this perspective, issues such as ‘vitality’ and ‘movement’, ‘being able to’, ‘freedom’ and ‘peace’ could be of importance.

Conclusion

This article describes the first data inventory and synthesis conducted on key patient issues in health research and quality of health care in Western countries. Patients are beginning to develop their own voice and agenda’s. This is done not only to enhance collaboration with professionals but also to empower the patient groups and it raises their awareness of issues, concerns and claims, their autonomy and self‐support. Often, they are involved in the appraisal of research, quality of care and policy on health care, but without a clear and systematic view on issues that matter from a collective point of view.

We conclude that the primary sources that resulted from our search seem to focus on the biomedical and methodological aspects of patient issues. Therefore, we searched for issues from experiences of patients in secondary and tertiary sources that cover a much wider range of experiential knowledge. This experiential knowledge includes issues originating from fundamental values (relevance, right to say and safety), quality of care and society and well‐being‐related values, e.g. quality of life, lifestyle and psychological and social impairment. Most of these issues, especially the issues related to daily life, do not find any reflection in the primary, scientific literature. Williamson 70 addresses patient activist issues from an emancipation point of view and presents 10 mainly UK‐oriented ‘principles’. Our review differs in that it collects issues international, includes chronic illness, disabilities and mental illness and considers both the health care and the health research domains. We gathered patient issues that matter before entering any negotiation. Therefore, the ‘criteria’ we set out to find extend beyond these ‘principles’.

The key patient issues found, appear to be interlinked among the two domains quality of care and health research. They are uniquely associated with neither specific diseases nor geographical areas, nor – for a significant part – with the separate domains.

Patient organizations cannot always cope with the participation possibilities attributed to them. 11 They do not have sufficient tools to be a professional partner in dialogue with health‐care professionals and researchers. Being invited to participate, does not automatically mean, one is genuinely included as a partner in appraising research and quality of care. Assymetric power relations may hinder that. 71 Specific inclusion strategies should be developed. 72 This article is a first step towards a better equipment of patient representatives. One possibility is to provide them with an appraisal tool. Available tools are reported to be poorly operationalized, to be incomplete and to have unclear boundaries and overlaps. 18 In order to support patients when appraising quality of health care, research activities and policy, we intend to take a next step and create a generalized appraisal tool: a patient ‘criteria’ list.

References

- 1. van Santvoort M. Disability in Europe: Policy, Social Participation and Subjective Well‐being. PhD Thesis, Rijks Universiteit Groningen, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Broerse JEW, van der Ham L, van veen S, Van Tulder M. Inventarisatie patiëntenparticipatie bij richtlijn ontwikkeling. VU Amsterdam: Athena instituut, Rapportage 1e fase, ZonMw (in press), 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Caron‐Flinterman F, Broerse JEW, Bunders JFG. The experiential knowledge of patients: a new resource for biomedical research? Social Science and Medicine, 2005; 60: 2575–2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stewart R, Oliver S. A Systematic Map of Studies of Patients’ and Clinicians’ Research Priorities. London, UK: James Lind Alliance, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abma TA. Patient participation in health research. Research with and for people with spinal cord injuries. Qualitative Health Research, 2005; 15: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abma TA. Patients as partners in health research. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 2006; 29: 424–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abma TA, Nierse C, Widdershoven GAM. Patients as research partners in responsive research. Methodological notions for collaborations in research agenda setting. Qualitative Health Research, 2009; 19: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abma TA, Broerse J. Patient participation as dialogue: setting research agendas. Health Expectations, 2010; 13: 160–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Herxheimer A. The rights of the patient in clinical research. The Lancet, 1988; 8620: 1128–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arnstein SR. ‘A ladder of citizen participation’. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 1969; 35: 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- 11. van de Bovenkamp HM, Trappenburg MJ, Grit KJ. Patient participation in collective healthcare decision making: the Dutch model. Health Expectations, 2010; 13: 73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nierse C, Abma TA. Developing voice and empowerment: the first step towards a broad consultation in research agenda setting. 2011, Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 2011; 55: 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baur V, Abma TA, Widdershoven GAM. Participation of older people in evaluation: mission impossible? Evaluation and Program Planning, 2010; 33: 238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oliver S, Clarke‐Jones L, Rees R et al. Involving consumers in research and development agenda setting for the NHS: developing an evidence‐based approach. Health Technology Assessment, 2004; 8: 1–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schipper K, Abma TA, Nierse C, van Zadelhoff E, van de Griendt J, Widdershoven GAM. What does it mean to be a research partner? An ethnodrama. Qualitative Inquiry, 2010; 16: 501–510. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johansen M, Oliver S, Oxman AD. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2006; 3: CD004563. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004563.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Healthcare, January 2009; University of York, 2008: 217–242. ISBN 978‐1‐900640‐47‐3. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Teunissen GJ, Abma TA. Derde partij: tussen droom en daad. Een verkennend onderzoek naar de patiëntenpartij en ‐criteria voor onderzoek, beleid en kwaliteit bij overheden en zorginstellingen. Tijdschrift voor Sociale gezondheidszorg, TSG 2010 nr 4, 2010: 189–196.

- 19. Joanna Briggs Institute . Reviewers’ Manual: 2008 Edition, Lockwood C. (ed.). Australia: Royal Adelaide Hospital, 2008, ABN: 80 230 154 545. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lithuania . Law on the rights of patients and compensation of the damage to their health, amended 1998, Vilnius, English translation, Number I‐1562, 1996.

- 21. WHO‐e . General Health Related Patient Support Groups. 2009, Available at: http://www.who.int/genomics/public/patientsupport/enprint.html, status per, accessed 1 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Herxheimer A, McPherson A, Miller R, Shepperd S, Yaphe J, Ziebland S. Database of patients’ experiences (DIPEx): a multi‐media approach to sharing experiences and information. The Lancet, 2000; 355: 1540–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bal R, van de Lindeloof A. Publieksparticipatie bij pakketbeslissingen. Leren van buitenlandse ervaringen. In: Zicht op zinnige en duurzame zorg, RVZ, Zoetermeer, 2005.

- 24. Grit K, van der Bovenkamp H, Bal R. De positie van de zorggebruiker in een veranderend stelsel. Rotterdam: Instituut voor Beleid en Management van de Gezondheidszorg (BMG), Erasmus MC, 2008: 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- 25. van Lindert H, Friele R, Sixma H. Wat vinden migranten belangrijk in de huisartsenzorg? Utrecht: De verlanglijst van migranten, Nivel, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Uiters E, van Dijk L, Deville W, Foets M, Spreeuwenberg P, Groenewegen PP. Ethnic Minorities and Prescription Medicine; Concordance between Self‐reports and Medical Records. Utrecht: Nivel, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. HFE . Health First Europe: HFE Health Survey 2007, 77 EU Opinion Leaders’ Views on the Future of Health. Brussels: HFE, 2007. http://www.healthfirsteurope.org, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schalock R, Alonso MAV. Handbook on Quality of Life for Human Service Practitioners. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation, 2002, ISBN 0‐940898‐77‐2. [Google Scholar]

- 29. WHO‐a . Marcial Velasco Garrido, Finn Børlum Kristensen, Camilla Palmhøj Nielsen, Reinhard Busse Health Technology Assessment and Health Policy‐making in Europe, Current Status, Challenges and Potential, EU Observatory study series nr. 14, Copenhagen, ISBN 978 92 890 4293 2, 2008: 23–26.

- 30. AF . Arthritis Foundation: Arthritis Prevention Control and Cure Act of 2009, H.R.1210/S.984. Washington, DC: Arthritis Foundation, http://www.arthritis.org , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31. EPF‐a . Toolkit for patient Organisations on meaningful patient involvement. Patients adding value to policy, projects and services, European Patients’ Forum, Brussels: EPF, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patients Association . (1) A guide to using your patient power; (2) Access to your medical records, a patients guide. Harrow, Middlesex, UK, http://www.patients‐association.com/advice‐publications/269 and.../326, 2009, accessed 1 December 2009.

- 33. Patient UK . Most Requested Support Groups. Leeds, UK, http://www.patient.co.uk , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34. WHO‐b . Everybody’s Business, Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes, WHO’s framework for action, ISBN 978 92 4 159607 7. Geneva: WHO, 2007: 20. [Google Scholar]

- 35. WHO‐c . The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), Geneva, Dutch translation, WHO‐FIC collaboration centre in the Netherlands, RIVM, 2002, Bilthoven, the Netherlands, 2001.

- 36. Sandor J. Ombudspersons and patients’ rights in Hungary In: Mackenny S, Fallberg L. (eds), Protecting Patients’ Rights? A Comparative Study of the Ombudsman in Healthcare. Oxon, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press, ISBN 1857758706. Chapter 4, 2004: 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wet betreffende de rechten van de patiënt, 22 augustus 2002, nr. 2002022737, Sociale zaken, volksgezondheid en leefmilieu./2004, Wet tot wijziging van de wet van 22 augustus 2002 betreffende de rechten van de patiënt – pijnbestrijding – palliatieve zorg, 24 November 2004, nr. 2005022587, Belgium, 2002/2004.

- 38. Brazinov A, Jansk E, Jurkovi R. Implementation of patients’ rights in the Slovak Republic. Eubios Journal of Asian and International Bioethics, 2004; 14, 90–91. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patientenrechte in Deutschland – Charta am 16.10.2002 vorgelegt, Pressemitteilung des Bundesjustizministeriums Nr. 54/02 vom 16. Oktober 2002, Deutschland, 2002.

- 40. Wiederholt M. (eds), Bendixen C, Dybjaer L, Storgaard Bonfils I. Danish disability policy, equal opportunities through dialogue, The Danish Disability Council. Kobenhavn, Denmark: Det Centrale Handicaprad, ISBN 87‐90985‐14‐1, 2002, accessed 1 December 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Heart and Stroke Foundation . http://www.heartandstroke.com , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009.

- 42. Al‐Anon . Al‐Anon/Alateen World Service Office, http://www.al‐anon.alateen.org , 2009.

- 43. Canadian Diabetes Association . http://www.diabetes.ca , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009.

- 44. Catsad . Canadian Association for Tay‐Sachs and Allied Diseases, http://www.Catsad.ca , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009.

- 45. ALA . American Lung Association: Cultural Diversity Policy. Washington, DC: ALA, http://www.lungusa.org , 2004, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46. NIA . National Institute on Aging: Caring for a Person with Alzheimer Disease. ADEAR Centre, http://www.nia.nih.gov 2009, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47. ALF . American Liver Foundation: Patient Toolkit. http://www.Liverfoundation.org , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 48. IAPO . What is Patient‐Centred Healthcare, A Review of Definitions and Principles, 2nd edn London, UK: International Alliance of Patient Organizations, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49. EPF‐b . Policy Recommendations, Patient Involvement in Health Programmes and Policy. Brussels: European Patients’ Forum, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 50. EPF‐c . Handbook for Project Coordinators, Leaders and Promoters on Meaningful Patient Involvement. Brussels: European Patients’ Forum, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51. EPECS . European Patients Empowerment for Customised Solutions – Declaration of Intent. Maastricht, the Netherlands: EPECS, http://www.epecs.eu , 2007, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 52. EIWH . European Institute of Women’s Health – Brochure. Dublin, Ireland: EIWH, http://www.eurohealth.ie , 2006, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Picker Institute . Principles, http://www.pickerinstitute.org , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009.

- 54. Planetree Inc . Principles, http://www.planetree.com , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009.

- 55. Shaller D. Patient‐Centered Care: What Does It Take? Oct 24, 2007, The Commonwealth Fund, Vol. 74: Picker Institute, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cochrane Collaboration . Stages of Consumer Input – Protocol and Review Stages. USA, http://www.cochrane.org , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57. WHO‐d . The WHO’s role and responsibilities in health research. Draft strategy on the research for health. 18 December 2008, The Executive board, 124th session, 2008b. 19, Article 56.

- 58. Kelson M. Patient and Public Involvement Programme (PPIP) Annual Report. UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2009. Item 4. [Google Scholar]

- 59. IAPO . Adressing global patient safety issues, an advocacy toolkit for patients’ organizations, IAPO, International alliance of patient organisations. Educational grant by F. Hoffmann‐La Roche, 2008.

- 60. Involve . P1: Getting involved in research grant applications, Guidelines for members of the public, NHS – National Institute for Health Research, and P2: peer reviewing research proposals, Guidelines for members of the public. DH Department of Health, http://www.invo.org.uk , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 61. JLA . How the James Lind Alliance Works. UK: JLA, http://www.lindalliance.org , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vilans . Kwaliteit van leven. Available at: http://www.Vilans.nl (internet 1 July 2009), 2009.

- 63. London Health Sciences Centre . Canadian Directory of Genetic Support Groups, Introduction to the Directory. London, ON: London Health Sciences Centre, http://www.LHSC.on.ca , 2009, accessed 1 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 64. PatientView . European Patient Group Directory 2008. Brussels: Burson‐Marsteller, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hjertqvist J. The Empowerment of the European Patient, Health Consumer Power House AB. Brussels, 2009: 19, 20, 28, 31, 36, 43. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Voice4Patients, http://www.Voice4Patients.com, 2010, accessed 1 December 2009.

- 67. Nierse C, Abma TA, Horemans A, van Engelen B. Kwaliteit en gezondheid. Integrale agenda voor neuromusculair onderzoek, Eindrapportage, ZonMw/UM/VSN/ISNO, 2007.

- 68. Dahlberg K, Todres L, Galvin K. Lifeworld‐led care is more than patient‐led care: an existential view of well‐being. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 2009; 12: 265–271. DOI: 10.1007/s11019-008-9174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Visse MA, Teunissen T, Peters A, Widdershoven G, Abma TA. Dialogue for air, air for dialogue. Toward shared responsibilities in COPD practice. Health Care Analysis, 2010; 18: 358–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Williamson C. Towards the Emancipation of Patients, Patients’ Experiences and the Patient Movement. Bristol: Policy Press, University of Bristol, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Baur VE, Elteren AHG, van Nierse CJ, Abma TA. Dealing with distrust and power dynamics. Assymetric relations among stakeholders in responsive evaluation. Evaluation, 2010; 3: 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Elberse JE, Caron‐Flinterman JF, Broerse EW. Patient‐expert partnerships in research: how to stimulate inclusion of patient perspectives. Health Expectations, 2010; 14: DOI: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]