Abstract

Aims We draw on the work of Nancy Fraser, and in particular her concepts of weak and strong publics, to analyze the process of parental involvement in managed neonatal network boards.

Background Public involvement has moved beyond the individual level to include greater involvement of both patients and the public in governance. However, there is relatively little literature that explores the nature and outcomes of long‐term patient involvement initiatives or has attempted to theorize, particularly at the level of corporate decision making, the process of patient and public involvement.

Methods A repeated survey of all neonatal network managers in England was carried out in 2006–07 to capture developments and changes in parental representation over this time period. This elicited information about the current status of parent representation on neonatal network boards. Four networks were also selected as case studies. This involved interviews with key members of each network board, interviews with parent representatives, observation of meetings and access to board minutes.

Results Data collected show that a wide range of approaches to involving parents has been adopted. These range from decisions not to involve parents at this level to relatively well‐developed systems designed to link parent representatives on network boards to parents in neonatal units.

Conclusion Despite these variations, we suggest that parental participation within neonatal services remains an example of a weak public because the parent representatives had limited participation with little influence on decision making.

Keywords: Fraser, health policy, _managed clinical networks, neonatal care, patient and public involvement

Introduction

Within the UK context, the 1990s were marked by an increasing interest in patient and public involvement (PPI) within the Department of Health (DoH) and the NHS. 1 These developments may be seen as a response to two major factors: public demands for a greater voice in decisions about their services, and demands from politicians for greater efficiency and effectiveness in the use of public funds, reflecting the growing influence of the New Public Management approach to health services management. 2 It can be argued that this latter development has its origins within the conservative government’s attempts to remodel the relationship between the NHS and service users along consumerist lines. Documents such as Working for Patients 3 and the Patients Charter 4 placed emphasis on individual ‘rights’ and ‘choices’. After the election of a Labour government in 1997, PPI became a central plank of health‐care policy 5 and developed to include greater involvement of both patients and the public in corporate decision making. 6 Legislation was passed, which requires NHS organizations to engage with service users in the planning and delivery of local services. 7 , 8 , 9 The central importance of PPI to the NHS has been reaffirmed in the Coalition Government’s new NHS White Paper – Equity and excellence: Liberating the NHS 10 .

Beresford 11 has argued that there has been an attempt to isolate participation from its broader political context and suggests that there is a search for safe options that divorce participation from concepts such as politics and ideology, replacing them with cosier terms like engagement.

There has also been a growing scepticism about the ability of the current PPI structure to deliver ‘meaningful’ participation. Within Parliament, legislators have been accused of fearing that democratic decision making would lead to unworkable populism and that expert government is better than public governance. 12

Staniszewska et al. 13 point out that the evidence base underpinning PPI is partial and lacks coherence. Little of the literature has attempted to theorize PPI, and little attention has been given to how areas of professional decision making are opened up to public involvement and the degree to which these boundaries are open to negotiation. This study of parental involvement in neonatal network boards addresses this issue.

Theoretical background: drawing on Nancy Fraser

Fraser 14 has developed the concepts of weak and strong publics. We suggest that this may provide a conceptual framework for the analysis of PPI in this study. She argues that a public is formed where private individuals come together to discuss issues publicly. The public sphere is distinguished from both the state and the economy and is seen as providing an important counterweight to both the power of the state and the interests of capital. However, the boundaries of the public sphere are not fixed, and differing social groups may have an interest in keeping certain issues in or out of this public domain.

Part of the process of challenging these boundaries may involve creating what Fraser 14 terms ‘subaltern counterpublics’, where subordinate social groups develop and circulate alternative understandings that challenge dominant views. Fraser makes a distinction between strong and weak publics. She defines a strong public as one where not only discussion takes place but also decisions are made. Weak publics are publics which discuss issues, but which have little chance of influencing decision making. The ability to access decision‐making processes may occur through having access to the state’s decision‐making bodies or being able to bring pressure to bear on them. 15

Related to the above concerns is Fraser’s concept of participatory parity. She argues that it is inadequate to suggest that participants should act ‘as if’ they were equal when participating in the public sphere. This is because inequality contaminates debate within publics. This occurs not simply because of inequalities in economic resources (the politics of redistribution) but also because of subtle processes of social and cultural distinction as expressed in dress codes, patterns of speech and body language (the politics of recognition). Here, Fraser references Bourdieu’s work on the role played by cultural capital in maintaining social distinctions. 16

For Fraser, achieving participatory parity is only possible if underlying economic and status inequalities are first addressed. Much of Fraser’s work takes place at the level of the nation state or relations between nation states; however, her analytical framework could be applied to initiatives designed to remedy the ‘democratic deficit’ in the NHS such as PPI.

Managed clinical networks and parental involvement in neonatal services

In 2003, the DoH recommended that neonatal services across England should be organized into managed clinical networks 17 and recommended that there should be at least two user representatives on each Neonatal Network Board. Despite a relatively wide‐ranging literature on parental involvement at the individual level, there is relatively little research literature that explores the experience of parental involvement in decision making in neonatal services, but there is research on other types of managed clinical networks.

Tritter et al. 18 in their work on user involvement in cancer networks make use of a ‘cycle of involvement’ linked to service improvements that are evaluated by service users as a way to develop participation in service delivery. Sitzia et al 6 in their research on the impact of patient participation on professionals and patients in cancer services found five types of outcomes of service user participation. These were being present, being consulted, representing the views of others, working in partnerships to improve care and proactive involvements to change service delivery. They suggest that a number of tensions can develop between professional and patient representatives and found that whilst service users are more likely to express their commitment to participation in personal terms, professionals were more likely to express their interest in terms of it being part of the job. A further area of tension was the tendency of some service users to discuss personal issues in meetings. Professionals, both clinical and non‐clinical, were often uneasy about this. A third area of tension was emotional commitment as service users felt that their participation entailed a degree of emotional commitment, and professionals were more likely to express little or no emotional commitment to patient involvement. The evidence presented also indicated that both clinical staff and service users tended to believe that senior NHS managers were only paying ‘lip service’ to patient participation.

Methodology

Ethics approval was given by the University of Warwick’s Humanities and Social Studies Research Ethics Committee, and an advisory group with representatives from the major stakeholders as well as parents met twice a year. This study was conducted in 2006–07. Two national surveys, using structured questionnaires, were sent to managers of all neonatal network boards in England to gather some basic information about the level and types of parental involvement being developed. The survey consisted of multiple choice questions with additional space to add free text comments and covered topics such as size of network board, parental representation and method of recruitment. The first survey was conducted in 2006 and the second in 2007, allowing us to capture developments and changes in parental representation over this time period.

In the first survey, 23 questionnaires were sent out to network managers and 22 returned, giving a response rate of 96%. In the second survey, 23 surveys were sent out and 20 responses were received, giving a response rate of 87%.

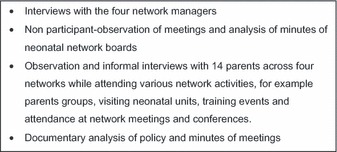

Case studies were undertaken of four networks in North and Central England to gain a more nuanced understanding of the process and mechanisms used for involving parents on neonatal network boards. The case studies were selected from the initial survey results to reflect different approaches to PPI being taken by network boards and made use of a variety of qualitative methods based on ethnographic fieldwork combined with formal interviews (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Methods used in case studies.

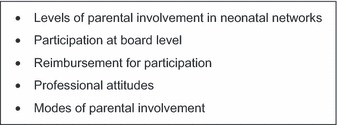

The team independently read and coded thematically a sample of the qualitative data to generate an agreed analytical framework for the data. The bulk of the data coding and analysis was then undertaken by AG with input from the other two authors. Emergent themes were developed iteratively from the data. Cross‐case analysis was also conducted to develop an analysis of the different modes of participation in operation within each case study and identify both common and divergent themes (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Emergent themes from analysis explored in paper.

Findings

The findings suggest that parental involvement in neonatal network boards offers relatively limited opportunities to influence decision‐making processes or alter agendas. This was manifested in different activities that were shared by the network boards with some mechanisms allowing for more parity than others.

Levels of parental involvement in neonatal networks 2006–07

The survey results gave an overview of the state of parental involvement in neonatal services. The number of parent representatives per network board in England varied from none to three in 2006 and from none to five in 2007. Nine networks in 2006 and eight in 2007, i.e. 41% in 2006 and 40% in 2007, reported that they had no parent representatives on their boards (Table 1).

Table 1.

Parent representation on neonatal network boards 2006–07

| Number of parents on the board | Number of boards in 2006 | Number of boards in 2007 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 9 | 8 |

| 1 | 3 | 2 |

| 2 | 6 | 7 |

| 3 | 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 22 | 20 |

The explanations for this included difficulties in recruiting and retaining parents, wishing to delay parental involvement until difficult decisions regarding the organization of the network had been made and preferring to engage with them in other ways.

‘There is no appetite for having one parent representative on our board, as the concern is that this will be a difficult environment for a parent to contribute. The preferred way forward is to hold a series of focus groups to obtain parent feedback and we would ask BLISS * to assist in this. The proposals are currently going through our Board’. (network manager).

Both the decision to delay involvement until after difficult decisions have been made or to restrict participation to the gathering of parental views via focus groups represents an attempt to control the boundaries of public involvement and in particular to exclude parents from direct participation in decision‐making processes. However, where boards had taken the decision to involve parents in their work, the survey results indicated that they had taken different approaches.

The majority of neonatal boards with parental involvement reported that they recruited parents either via staff recommendations or through an advertisement and interview procedure developed in conjunction with BLISS. In some cases, a combination of these methods was used. However, other methods used by networks included recruiting via Maternity Services Liaison Committees, neonatal unit parents’ groups, advertising through the units across a network, community road shows, direct invitation, via community nurses and letters to parents.

The data suggest that the types of parents who become involved in neonatal networks are relatively homogeneous. They are female (only two networks reported involving fathers), predominately white and tend to be from professional backgrounds. Epidemiological evidence suggests that families with a lower socio‐economic status and families from certain ethnic minority groups are more likely to experience a premature birth or the difficulties associated with giving birth to a sick baby. 19 However, at present, the parents involved within neonatal networks do not generally reflect this. This has the effect of rendering invisible the views of parents from lower socio‐economic groups and ethnic minorities. Engagement with a more demographically representative group of parents would not automatically lead to the creation of a stronger public but if involvement initiatives could aim to involve people who are representative.

The data indicated that for some people involved in the recruitment of parents, the interviewing process represented an opportunity to check that potential recruits ‘do not have an axe to grind’ (network manager). In others, it represented a concern not to involve people who might be actively involved in local public campaigns related to the provision of neonatal services. As one board member put it:

‘I think it is essential that parents subscribe to the current ethos in neonatal services, instead of wanting a level 3 neonatal unit on their door step’ (clinician at network board meeting).

This suggests that the scope and nature of that participation is closely managed and it appears to deny participants access to the type of social networks which might lead to the development of a form of counterpublic, capable of challenging the medical and professional domination of decision making.

Selection by interview and selection by staff recommendation both represent approaches in which the board effectively controls which parents are to participate in the work of the network. However, this is not the only approach. One of the network case studies facilitated the setting up of parents’ groups in each of its neonatal units. These user groups were invited to send a representative to a network wide parents’ group, which in turn chose two of its members to participate in network board meetings. In this approach, it is the parents who choose their representatives as opposed to the board. This approach by itself did not automatically improve the representative nature of involvement or create a strong public; however, it did give parents some control over who represented their views at board levels and created a social space where they could develop their own views independently of those responsible for running and providing the service.

Participation at board level

Once selected for participation, there were still hurdles for parents to overcome if they were to meaningfully participate. Board meetings were frequently scheduled during office hours. This may not be the best time for some parents, given their likely caring commitments and possible employment commitments. Developing mechanisms that would allow parents to have an input who cannot attend these meetings may therefore be essential, but unfortunately, examples are rare. To deal with this, one board set up a ‘partnership group’. This met on a Saturday. This meeting then fed the views of parents into the network board meetings.

The structure of network board meetings was also relevant to whether parents felt that they were able to contribute. The average network board had a membership of 20 or more people, made up of a combination of clinical, managerial staff and commissioners. Where theses boards had involved parents, they had, on average, recruited two parents, although it was not unusual for one or both not to be present. Both clinical and managerial members of these boards had social status based on their professional expertise. Although parents had experiential knowledge based on their use of neonatal services, it was not always clear that this knowledge carried equal status within the arena of board meetings.

Board meetings themselves are often tightly chaired. Frequently, a report was received in writing with an oral introduction from the lead person involved in its production and often accepted with minor amendments. This made it difficult for parents to intervene if they did not have previous knowledge of the issues. Parents could experience these meetings as intimidating and difficult to contribute to, particularly when they first attended so participatory parity was difficult if not impossible to achieve.

‘I have to admit that I was terrified walking in that room today. I don’t know why, it wasn’t as if they were all going to quiz me or anything’ (parent on her first Board meeting).

Furthermore, many neonatal networks are struggling to provide the best level of care for neonates within limited budgets (BLISS). 20 These issues can also effect participation at board level. As one parent explained after a board meeting discussion about maintaining staffing levels,

‘I feel that the meeting has been depressing. I think the people present are doing the best they can in difficult circumstances and therefore it’s not easy to criticise them’ (parent representative).

The two parents present at this meeting had wanted to raise the issue of how professionals communicate/interact with parents. However, they felt that they had been unable to do this because the people present seemed to be struggling to cope with basic problems such as inadequate funding and insufficient staffing. Compared to this, developing staff communication skills seemed a low priority.

The danger inherent in these types of involvement structures is that they create nominal equality of participation within structures that are difficult for lay people to engage within, thus making the achievement of participatory parity difficult to achieve. It is partly in response to these problems that various service user movements have developed what Fraser 14 terms counterpublics outside of these types of structures.

Parental representation at other levels within the networks

Representation on network boards is only one forum within the networks where parents may contribute. Both surveys asked whether parents were involved in network subgroups or had other mechanisms for involving parents (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mechanisms for involving parents

| 2006 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|

| Parents involved in subgroups | 7 | 11 |

| Other mechanisms for involving parents | 13 | 15 |

In the 2006 survey only seven networks reported that they regularly involved parents in subgroups, with one additional network reporting that parents were involved as and when needed. In the 2007 survey, 11 networks reported that they involved parents in the work of subgroups. Examples of the types of these subgroups were transport, nursing, clinical governance and audit, developmental care and bench marking.

Although the number of parents who were members of network boards did not significantly change between 2006 (22 parents) and 2007 (20 parents), these figures seem to indicate that there has been a significant increase in parental involvement in network activity outside of the board meetings. These subgroups are frequently smaller than board meetings and deal with issues more directly related to service delivery. They may therefore provide an environment within which parents feel that they are more able to effectively utilize their experiential knowledge of neonatal services.

The repeated survey also asked whether networks have other mechanisms for involving parents in their work. In the 2006 survey, 13 networks responded positively to this question. This rose to 15 in the 2007 survey. Interestingly, the types of engagement reported under this heading also appear to have changed. In 2006, examples given in response to this question included engagement through Maternity Services Liaison Committee, e‐mail, post, website and Overview and Scrutiny Committees.

The networks that responded positively to this question in 2007 gave examples that appeared to reflect a shift toward more direct forms of engagement. These included involving parents in the review of neonatal units, focus groups, the development of unit parent groups, surveys, parents giving presentations at network events and regular contact with parents via e‐mail, telephone or meetings.

The role of intermediaries

Within the board meeting itself, the Chair can play an important role in ensuring that parents are welcomed to meetings, that jargon is explained and that they get an opportunity to contribute.

‘We’ve got a large clinical representation on the board, so if you get sort of lost in the clinical discussion, then you almost need a translator at the end of it for the users. So our Chair is very good at either directing me or the clinical lead to translate for the User reps and ask for their feedback on it, and not just them. You’ve also got commissioners and other people who aren’t necessarily au fait with all the clinical jargon that spills out of consultants’ mouths quite easily, even if they try not to’ (network manager).

However, this sort of intervention, although important, does not address the concerns of both professionals and parents regarding ‘tokenism’. The evidence gathered from the case studies suggests that the role played by professional board members who are prepared to facilitate the development of parental involvement is central. It appears that often this role, if it is taken up at all, is taken up by network managers.

This does not necessarily happen in a pre‐conceived manner. One network manager recounted that she set out with two basic ideas, that parents should have a voice at board meetings and that their involvement should not be tokenistic.

From these premises, parental involvement developed organically via a process of consultation with parents. At the beginning of the study, this network had recruited four parents, two of whom attended board meetings. One of these had also been a member of a reviewing team which visited the units in the network. This network now has six parents involved in its work, two of which attend board meetings. However, parents are also involved in five board subgroups and have been involved in assessing the neonatal units in the network. This has resulted in the parents producing action plans for the board designed to address the issues that they have identified.

Another network participating in the study began from a similar starting point, but developed an alternative approach. In this case, the network manager felt that parents’ views would carry more weight if they were ‘translated’ into the format that other professionals use. This was done through the setting up of a parent task group. The group was set up to pursue parental recommendations derived from visits to the units in the network. The task group is composed of two parents and ‘parent champions’ from each unit in the network. The Task Group’s role is to ensure that the parents’ recommendations are acted on. This approach is intended to create a more structured and transparent approach to parental involvement. The lead nurse in the network feels that

‘this approach is much less tokenistic than it could have been’ (lead nurse).

The approaches to parental involvement described earlier are not without their problems. However, they do represent an important development beyond simple parental presence at board meetings. They help to address the issue of ‘participatory parity’ by creating structures which lay people may find easier to engage with. The growth of parents involved in various activities outside of Board meetings, noted in the survey, suggests that this type of development is not unique, but reflects a broader trend, at least in those networks that have begun extending the participation of parents.

Reimbursement for participation

Reimbursement was variable across networks. The 2006 survey indicated that 11 networks paid travel expenses to parents, and nine reported that they paid for childcare costs. In 2007, 16 networks reported that they paid travel expenses, and 12 reported that they paid childcare costs. In 2006, three reported that they would consider paying parents for a specific contribution to a meeting with one indicating that this happened routinely. In 2007, five networks reported that parents are paid for attending meetings, but two of these indicated that it was at the network managers’ discretion (Table 3).

Table 3.

Reimbursement for participation

| 2006 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|

| Travel expenses | 11 | 16 |

| Childcare | 9 | 12 |

| Attendance at meetings | 1 | 3 |

It is unlikely that parents from lower socio‐economic backgrounds will be able to participate within neonatal networks unless they are offered adequate reimbursement for the costs incurred by participation. This is also an issue of social recognition, reimbursement carries with it both an economic and symbolic value. From a sociological perspective, the lack of reimbursement represents a form of what Bourdieu (16) terms ‘symbolic violence’, i.e. it represents a tacit form of discrimination.

Professional attitudes

Although PPI is now a cornerstone of every aspect of the NHS, it cannot be assumed that this is accepted by all. Some professionals remained sceptical of the ability of parents to contribute to strategic decision making in the NHS. One clinician remarked:

‘Involving parents in high level decision making can be quite destructive because they don’t have a handle on all the different angles’.

Even where board members had a positive attitude to parental involvement, this may not be shared by staff in neonatal units. If parental input is confined to one or two people attending board meetings, it is unlikely to become embedded in other aspects of the networks’ work. Where parental involvement was accepted, there were different opinions concerning the specific roles of parents in neonatal networks. These were rarely explicitly articulated but appeared to shape the approach taken to parental involvement and led to the construction of publics of differing strengths.

Modes of parental involvement, participatory parity and the politics of recognition

Parents played different roles on network boards, depending on how differing networks conceived of and organized parental involvement. Broadly speaking, these roles fell into three main types, each with differing levels of participatory parity. These were as sources of information, consultants or as representatives of other parents.

These modes of parental involvement were not mutually exclusive, but the degree of participatory parity was the least strong when parents were solely used as sources of information and strongest when they represented other parents through links with parent groups external to the boards.

Parents as sources of information

Here, parents are seen as a source of raw data collected in a number of ways, e.g. via a survey or via the use of focus groups to be analysed and the results fed into the networks decision‐making processes. For example, one network manager described the approach that had been taken by her board to the unit designation process. This consisted of an initial ‘complete option appraisal process’ that involved assessing what the network currently provides, current workloads and finances. This information would then be used to generate various options. The board then chooses one of them. Once implemented, it would be regularly reviewed, with parents being consulted via parent questionnaires.

This approach was frequently adopted by networks that were sceptical about the value of parental membership at board level. It has the advantage that information from a relatively large number of people can be obtained. However, the type of information produced is determined by the agenda of the board, rather than the parents using the service. It also prevents the formation of social networks between parents and precludes parents from any involvement in the decision‐making process.

Parents as consultants

This approach recognized that parents not only possessed important information but that their specific experiences as users of the service meant that they had the potential to make a contribution to the decision‐making processes of the network. For example, in one network, the nursing subgroup was working on developing service benchmarks. A mother was involved to give a parental perspective on service quality.

The parent involved reported that she found it much easier to make an active contribution at this level compared to board meetings. This was because the meeting focused much more on issues of direct care, which she felt she could comment on, as someone who has used the service and thought a lot about the needs of babies and their families. This contrasted with discussions at board meetings concerning budgets or network structure. These types of meetings were also generally smaller than board meetings.

The difficulty with the ‘parents as consultants’ approach is that it frequently relied on a relatively small number of parents and difficulties arose when a parent was unable to continue participating. It also left parents open to the accusation that their views were not representative of the wider parent population that neonatal networks serve. This kind of criticism is likely to come to the fore where parents find their views in conflict with those of professional board members. It offers a rationale for members of a board to reject parental suggestions. For example, parents had produced a short document describing parental experiences of a neonatal unit, and one professional criticized the document on the grounds that it was ‘unrepresentative’ of parents’ experiences.

In some instances, this form of involvement can be used to justify a lack of wider consultation. For example, one network manager felt that the outcome of a public consultation involving her network was likely to be a foregone conclusion. However, she pointed out that parents had been present at board meetings where the issues had been discussed, so there had already been some public/user consultation. In these circumstances, participation can be used to legitimize existing decision‐making structures and processes.

Parents as representatives

In this approach, the role of parents on network boards is to represent the views of other parents who have used neonatal services. This is something that most network boards see as desirable, but relatively few have developed mechanisms that would allow it to develop. The term representative is used here to specifically refer to a form of parental involvement where mechanisms have been developed, which link parents on network boards to a wider group of parents who use neonatal services.

This approach has a number of advantages. It potentially increases the numbers and diversity of parents who can contribute to the decision‐making processes either directly or indirectly. It also has the potential to provide a greater opportunity for parents to place on the board agenda issues of importance to them, as they emerge through their own discussions. Although this approach is relatively rare, it has been adopted in a number of networks in various forms.

One network case study adopted this approach. It consisted of parents’ groups based in neonatal units sending representatives to a regional parents’ group which in turn sent two representatives to the network board. The regional parents’ group, as well as linking local units to the network at a regional level, allowed the parents to exchange experiences and advice, provide peer support to one another and potentially develop their own ideas about how the running of neonatal services. As such, they could provide the basis for forming a decision‐making process capable of interacting with professional decision‐makers on a more equal footing.

The major difficulty here is that this approach requires a relatively large commitment in terms of time and effort from the parents involved.

‘Between this (running a local parents’ group) and the network it is taking up a lot of time and effort. It is hard fitting it round home life, and I don’t want to spread myself too thinly. I think I need to stay focused and maybe dedicate a day every fortnight to doing BLISS/network stuff then I can keep on top of it – this is becoming like a full‐time job!’ (parent representative).

In particular, it required the successful setting up and running of local parents’ groups to provide the basis for this approach. The experience of the networks that have implemented this model suggests that this is not a straightforward process, particularly where large geographical distances are involved.

There are also major difficulties involved in the running of these groups. This is because the groups frequently perform two separate but related functions: being both a support group for local parents and a parent forum on service issues.

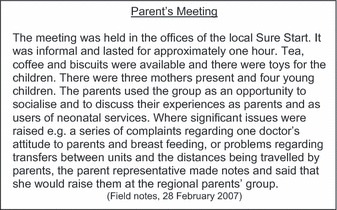

Managing these two functions is a difficult task and one that parents may require support to carry out successfully. The following is a description of how one such group operates (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Summary of parent meeting.

Despite these potential difficulties, this approach gives parent representatives at board level a clearer role and status. It also creates an important link between the network board and what is happening in local units. However, there is still the danger, as Wakefield and Poland 21 point out, that this type of structure will only allow those individuals to directly participate who have become familiar and comfortable, perhaps through education, with the cultural modes of expression required by those organizing the involvement process. These types of approaches to building public participation can, therefore, have the unintended consequence of concentrating the power of particular groups into the hands of a few spokespersons whilst at the same time introducing social distance between those speaking and those being spoken for. 16

Conclusions

Fraser’s ‘politics of recognition’ 14 is predicated on there being some level of participatory parity. In the majority of neonatal networks in 2006–07, parent involvement was being constructed, we would argue, as a weak public, lacking in general participatory parity and therefore unable to challenge the boundaries and discourse of the boards. The development of involvement in neonatal boards has been a predominately top–down process. Parents have rarely been asked how, when or where they would like to be involved.

Whilst it is beyond the power of neonatal networks to remedy broader issues of inequality among its members, it is possible to deal with lessening social and economic inequalities by, for example, addressing the issues of reimbursement. It is not only financial recognition that is at issue here. Both clinical and managerial members of these boards carry with them significant social status based on their respective domains of professional expertise. It is these professional members of a board and in particular the core management team that play a significant role in determining both the written and unwritten agenda of the board. These factors make it difficult for parents to challenge this agenda or professional judgements unless the issue involved directly related to parental experience of neonatal services.

It is only where parents are members of boards in a representative capacity that the issue of parental involvement is related to a need for wider parental participation. However, the institutional arrangements designed to ensure the accountability of representatives to their external publics (usually organized around a particular neonatal unit) are largely embryonic or non‐existent. There is also evidence that action is taken to exclude parents who might be actively involved in local campaigns that relate to neonatal services.

It is clear that some networks are making progress. As described earlier, one of the case study networks had established parents’ groups based in neonatal units sending representatives to a regional parents’ group which in turn had representation on the network board. It is also clear that many of the parents involved in the work of neonatal networks greatly valued the opportunity to contribute positively to the development of a service that had provided them with medical assistance and support at a time of extreme crisis in their lives.

There are a number of practical steps that neonatal networks could take to address some of the weaknesses we have identified.

Networks should develop a clear idea about what they want to achieve through involving parents in their work, which will determine the type and level of involvement and the nature of the support and training that staff and parents may require. Accessing parents as sources of information, as consultants or as representatives of other parents places very different requirements both on network staff and on parents.

Each network could nominate one person to act as the network’s parental involvement coordinator. This person would be responsible for developing the networks approach to parental involvement in partnership with the network board and parents. In most cases, this person will be the network manager.

Training packages could be developed, which reflect the diversity of approaches to parental involvement within neonatal networks. This may involve working with networks beforehand to design an appropriate training package. Ideally, training should be run jointly for both parents and network managers.

There is a tendency for parental involvement to exclude already marginalized groups. If this tendency is not checked, there is a danger that the process of parental involvement will entrench, rather than reduce, health inequalities. It is, therefore, important that networks develop models of participation that are as representative as possible of the population they serve.

All networks who involve parents in their work could make arrangements to recompense parents for any expenses incurred as a result of the involvement process (e.g. travel, parking and childcare) and make payments that recompense parents for the time, effort and inconvenience that involvement requires. This is particularly important if people from lower socio‐economic groups are not to be disadvantaged by the involvement process.

However, using Fraser’s framework shows that the boundaries of public debate and participation are dynamic and, in certain instances, highly contested. These boundaries do not merely consist of which issues are in or out of the public sphere, but also which solutions may be deemed acceptable or unacceptable resolutions to a particular problem. Fraser’s work also reminds us that although much of the original impetus for PPI came from the formation of subaltern counterpublics in the fields of health and social care, the structures that have emerged do not reflect this and all too frequently positively exclude these groups.

Beresford 11 has commented on the weaknesses of analysis which isolate participation from its political context. We would suggest that Fraser’s work provides us with a framework for identifying precisely these aspects of involvement.

Despite these strengths, our analysis suggests that we need to engage with Fraser’s concepts critically. In particular, her conception of what constitutes a ‘public’ is very broad lacking clear definition. The concept of ‘participatory parity’ is useful, and this paper extends it to reflect the different modes of participation explored here. The elaborated concept of participatory parity could be used to investigate the type and quality of any new or existing engagement activity. In this way, Fraser’s work can be used to generate a framework for evaluating user participation, which helps us to analyse what is taking place within new and existing participation initiatives and importantly to begin to identify what an alternative approach might look like.

Funding

This research was funded by the West Midlands Specialised Commissioning Team, BLISS and Grace’s Research Fund.

Acknowledgements

In particular, we would like to thank the parent representatives, staff, members and managers of the neonatal networks for their time and interest in this study. The writing of this paper was partially supported by funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

BLISS is the leading national charity in the UK in neonatal care.

References

- 1. Barnes M. The People’s Health Service? Brmingham: University of Birmingham Health Services Management Centre, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rowe R, Shephard M. Public participation in the new NHS: no closer to citizen control? Social Policy & Administration, 2002; 36: 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Department of Health . Working for Patients. London: Department of Health, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Department of Health . The Patient’s Charter. London: Department of Health, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Milewa T, Harrison S, Ahmad W, Tovey P. Citizens’ Participation in Primary Healthcare Planning: innovative citizenship practice in empirical perspective. Critical Public Health, 2002; 12: 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sitzia J, Cotterill P, Richardson A. Interprofessional collaboration with service users in the development of cancer services: the Cancer Partnership Project. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 2006; 20: 60–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. HMSO . Health and Social Care Act. London: HMSO, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8. HMSO . National Health Service Act. London: HMSO, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9. HMSO . Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act. London: HMSO, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Department of Health . Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS. London: Department of Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beresford P. User involvement in research and evaluation: liberation or regulation? Social Policy and Society, 2002; 1: 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pugh J. Hansard, 21 October, col 914–916, 2009.

- 13. Staniszewska S, Herron‐Marx S, Mockford C. Editorial measuring the impact of patient and public involvement: the need for an evidence base. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 2008; 20: 73–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fraser N. Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy in Fraser, F. Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the ‘Postsocialist’ Condition. London: Routledge, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davies JS. The limits of partnership: an exit‐action strategy for local democratic inclusion. Political Studies, 2007; 55: 779–800. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bourdieu P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London: Routledge, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Department of Health . Report of Department of Health Working Group on Neonatal Intensive Care Services. London: Department of Health, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tritter J, Daykin N, Evans S, Sanidas M. Improving Cancer Services Through Patient Involvement. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gardosi J, Francis A. Key Health Data for the West Midlands. Birmingham: Department of Public Health and Epidemiology, University of Birmingham, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20. BLISS . Neonatal Services – Are They Improving? First Expenditure Survey of Department of Health funding of Neonatal Networks. London: BLISS, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wakefield EL, Poland B. Family, friend or foe? Critical reflections on the relevance and role of social capital in health promotion and community development. Social Science & Medicine, 2005; 60: 2819–2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]