Abstract

Background In 2008, the World Health Organization issued a callback to the principles of primary health care, which renewed interests in social participation in health. In Guatemala, social participation has been the main policy for the decentralization process since the late 1990s and the social development council scheme has been the main means for participation for the country’s population since 2002.

Aim The aim of this study was to explore the process of social participation at a municipal‐level health commission in the municipality of Palencia, Guatemala.

Methods Analysis of legal and policy documents and in‐depth interviews with institutional and community‐level stakeholders of the commission.

Results The lack of clear guidelines and regulations means that the stakeholders own motivations, agendas and power resources play an important part in defining the roles of the participants. Institutional stakeholders have the human and financial power to make policies. The community‐level stakeholders are token participants with little power resources. Their main role is to identify the needs of their communities and seek help from the authorities. Satisfaction and the perceived benefits that the stakeholders obtain from the process play an important part in maintaining the commission’s dynamic, which is unlikely to change unless the stakeholders perceive that the benefit they obtain does not outweigh the effort their role entails.

Conclusion Without more uniformed mechanisms and incentives for municipalities to work towards the national goal of equitable involvement in the development process, the achievements will be fragmented and will depend on the individual stakeholder’s good will.

Keywords: Guatemala, health commissions, primary health care, social participation

Introduction

In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) called its member countries to review their health policies in the light of the primary health‐care approach (PHC). First implemented in the late 1970s, through the Alma‐Ata declaration, PHC was a comprehensive strategy that addressed broad determinants of health, such as sanitation and education, as well as expanding the coverage levels and providing health‐care services to previously un‐reachable populations. 1 , 2 In 2008, the WHO added specific reforms to improve health coverage, service delivery, public policy and leadership within health systems. 3 It was this ‘callback to Alma‐Ata’ that brought on a renewed sense of importance to all of the components of PHC, including social participation.

According to the PHC approach, people have the right and the duty to participate collectively and/or individually in planning and implementing their own health care. Participation was supposed to lead to an increase in the health system’s responsiveness while providing a tool to help balance out economic costs. At the same time, it was meant to be an empowering process that would allow local communities to make decisions on the policies that directly affected their own well‐being. 2 However, very few states were able to provide the context for this kind of participation to happen and the original participation component of PHC changed to fit other health‐sector goals. The result was that obeying one’s physician, volunteering as a community health worker and taking part of decision‐making processes were all seen as a equally acceptable forms of participating in the health system. 1 , 4 , 5 , 6

As with participation within the PHC approach, decentralization processes use participatory policies as a means to carry out the devolution of power, resources and decision making to local populations. Ideally, decentralization creates spaces for participation where local communities and authorities can discuss, appraise, plan and monitor institutions and organizations as well as policies put forth by citizens or institutions. 7 The premise of this kind of participation is that through involving authorities, institutions and citizens, there can be a de‐concentration of responsibilities and resources from the central to the local level, which could make the state apparatus more responsive to previously ignored needs. 8 , 9 However, the state needs to keep a strong role as a steward and provide technical, financial and institutional support. 3

Most countries in the Latin American region recognize the importance of social policies in health as a means to identify their own population’s needs, to include previously excluded groups in decision‐making processes, and to achieve a more equitable access to health services. 10 , 32 , 33 , 34 However, different countries have different schemes and regulations for social participation in their health systems, which affect participation in service design and delivery, and in the way health‐care needs are dealt with. While Brazil implemented a health council scheme that has clear guidelines on how to involve community‐level representatives and makes community participation mandatory to receive federal funding for health services, other countries like Colombia and Guatemala have more ambiguous regulations. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 Social participation is a key component of Guatemala’s decentralization process and an essential part of the country’s health system, which is based on the PHC approach. Guatemala has a legal framework that states that participation is important for the health and general well‐being of the population, but there is lack of knowledge about how the Guatemalan participation scheme is carried out in municipal‐level health systems. Because of this, our goal was to explore the way the social participation process works in a municipal‐level health commission.

Background

Social participation in health in Guatemala

Guatemala is a country that has 12.9 million inhabitants, most of whom live in poverty (51%) and/or in rural areas (54%). Poverty levels are higher among the rural population, where two‐thirds of the population is poor 15 , 16 and the World Bank 17 named it one of the most unequal countries in the world in terms of income concentration and distribution.

The peace accords of 1996 ended a 35‐year internal armed conflict and provided the setting for the Guatemalan state to recognize the importance of equitable social and economic development. To reach this goal, a decentralization process that highlighted the need for the Guatemalan citizens to be active participants in the planning and executing of public policy and in controlling the national, provincial, and municipal levels of government was set in place. 18 , 19 To implement the decentralization policy, the state emphasized the role that municipal governments play in adjusting national policies to local needs. The policy lets each municipality decide when to start this process and what should be incorporated in it. This helps to tailor a national policy to specific needs and lets each municipality decide when it is competent enough to take on the added responsibilities that come with decentralization. 20 , 21

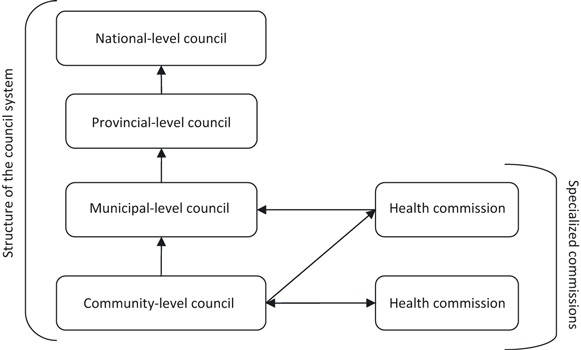

Since 2002, Guatemala has a formal system of participation based on social development councils organized at the community, municipal, provincial and national levels (Fig. 1). This council system is a bottom‐up structure with a legal framework that supports its work in the decision‐making spaces that the decentralization process created. However, the law does not specify any mechanism to ensure the participation of any stakeholder at any level. 18

Figure 1.

The Guatemalan social development council structure.

Each level of the council has specialized commissions, one of which is the ‘health commission’. Its goal is to bring the health sector together with the council scheme and to provide a space for social participation regarding specific health issues. 18 , 22 , 23 , 24 According to the legislation, municipal‐level health commissions (MHC) are in charge of tailoring national policies to municipal needs, implementing programmes and policies and should be the coordinating body for all health‐related work in the municipality. Community‐level health commissions (CHC) have the responsibility to keep the community’s environment healthy, to provide information about disease outbreaks and to establish emergency plans for transporting the sick. Additionally, CHC must monitor health policies and provide feedback to the MHC. 18 , 23

Methods

The setting

Guatemala is divided into 22 provinces, each of them divided into municipalities that act as the political unit of the country. Palencia is one of the municipalities in the same province as Guatemala City, and it has a total population of 55 410 people. Of them, 70.3% live in rural areas and 38% of all the inhabitants are poor. 25 Of that total population, almost 99% is non‐indigenous and Spanish is the only language spoken. In Palencia, 70% of the population has regular access to drinking water and electricity, while only 20% have access to sanitation. Most of the population lives as subsistence farmers. In the municipality’s social development council scheme, there are 49 community‐level councils and one municipal‐level council. 26 The municipal‐level health commission, a part of the municipal‐level social development council, has been meeting since October of 2008.

For the Ministry of Health (MoH), Palencia is one of the seven districts in the north‐eastern health area of the province of Guatemala. In regard to infrastructure, the MoH has one health centre, seven health posts and one oral health clinic. The closest hospitals are the two national referral hospitals located in Guatemala City, about 30 km from the centre of Palencia. The district also has one non‐governmental organization (NGO) that outsources care through the ‘extension of care’ programme. They have seventeen miniclinics to provide care through local community health workers and ambulatory staff that visits each post about once a month. The municipal government funds one medical and one dental health clinic, as well as keeping a nutritionist on staff. There are also two private laboratories and one private physician.

In 2009, the MHC worked on the implementation of a health promotion plan that aimed to coordinate the work that the different institutions that work in Palencia were carrying out. The plan focused on reproductive health, potable water projects and the prevention of contagious diseases, and included a healthy schools initiative. It was piloted in two communities, which are the only two that are routinely invited to participate at the health commission meetings.

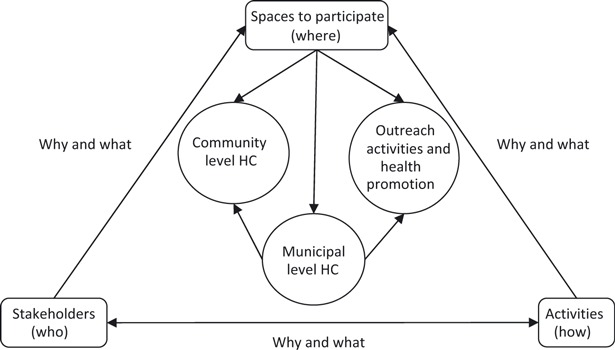

A framework for understanding social participation

The structure of this study comes from Rifkin’s 27 work on community participation in health programmes. The original framework called for asking who, why and how participation took place, to which we decided to add where it occurred and what participation meant to each stakeholder in the MCH (Fig. 2). The figure tries to represent the complexity of many stakeholders participating at local‐level health systems. Each one might have its own participation agenda and expect specific results from the process, but this will depend on their definition of the role of each participant and expectations of who should do what.

Figure 2.

A framework for understanding social participation in local‐level health systems in Guatemala.

Our framework proposes that the ‘who’, the ‘how’ and the ‘where’ are connected by the ‘why’ and the ‘what’ and that the relationship between these questions shapes the health commission and its work. There are many institutions and stakeholders working in municipal‐level health systems. However, not all of them decide to be a part of the MHC or are included in it. Identifying ‘who’ is coming to the meetings, who is not, and ‘what’ they understand as social participation provides a context to understanding the next key question of ‘why’, which refers to the specific reasons or motivations that each stakeholder has for entering and staying in the social participation process. Asking ‘how’ and ‘where’ each member of the health commission participates refers to their role in the process. It includes what others perceive of them and their role and vice versa. Our theoretical framework explains how all these questions are the separate components of the same process. However, in practice, it is difficult to break up the answers to all of these questions. Because of this, we decided to present our results by linking together ‘who’ and ‘why’, and ‘how’ and ‘where’.

Data collection and analysis

We applied a qualitative approach to explore the process of participation in Palencia’s health system. We used documentary analysis for the Guatemalan legal framework on social participation, which provided the background for identifying what the participatory structure should look like at the municipal level. 18 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 29 We then interviewed 16 members of the municipal‐level health commission (Table 1) and used a semi‐structured interview guide with questions that reflected our framework. The guides contained questions regarding what social participation meant to the members of the commission and included questions about the process, attendance, inclusion of other stakeholders, the MHC as a space for social participation and each stakeholder’s role. 30 , 31

Table 1.

Distribution of the interviewees who participate in the municipal‐level HC

| Interviews | Group | Sex | Educational level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | |||

| 3 | Provincial health authorities | 1 | 2 | Postgraduate degrees |

| 4 | Municipal authorities | 2 | 2 | Some university or university degree |

| 6 | District health authorities | 3 | 3 | Some university or university degree |

| 3 | Community HC representatives | 3 | 0 | Some primary school |

HC, health commissions.

Permission was obtained to record and transcribe fourteen of the sixteen interviews. With the remaining two, we took notes and then utilized the information in the same way as with the transcriptions.

We analysed the information from the interviews and from the legal framework using role‐ordered matrixes that allowed us to explore each stakeholders’ perspective from their own role in the process of participation in the municipal‐level health commissions (HC). 30 , 31

Ethical considerations

In Guatemala, researchers who are not conducting clinical trials or human testing do not need to go through an ethical committee. However, we procured ethical clearance with the local government, the MoH, and the communities that participated in our study by presenting our project and our methodology to all the stakeholders. We also obtained informed consent from interviewees and informed them that they could withdraw at any time without any consequences. We asked permission to tape‐record the interviews or to take notes, guaranteed anonymity to all of the participants, and later informed of the results of the research to all of the informants.

When reporting the results, we felt that limiting the identification of the interviewees was an important component of the promise of anonymity we issued during the data collection. As a result, we only state to which of the groups the stakeholder belongs, because there are so few participants in the municipal‐level HC that it would be easy to discover the identity of the person we interviewed.

Results

Who is in the municipal‐level HC and why they attend the meetings?

There are two types of members in Palencia’s MHC: the ‘community stakeholders’ and the ‘institutional stakeholders’. The latter includes all the participants that act as representatives from the municipal government, NGOs, or from the MoH (at the district or provincial level). Most of these stakeholders have university and graduate degrees either in social work or in medicine. When asked for their motivation to participate, one stakeholder from the health district stated that ‘The unrealistic financing that we get doesn’t meet the needs of this district. What we have to do is to work together with other institutions and gain support from them so that they can help with health promotion or financing projects’. For them, the municipal health council is a space to work with other institutions that have more funding or that carry out the same kind of work. The institutional stakeholders feel that using the MHC and the health promotion plan, they can improve the coordination levels of their work and communication. In that sense, they think of the MHC as a way to improve the health indicators and the performance of the health services. This plan is the tool they use to promote ‘the strengthening of this municipality’s health status, but of an integral state of health that provides more than curative services…and that focuses on preventive health’ [Stakeholder from the municipality].

The second type of stakeholder groups the representatives from the CHC. They are community members with no formal education and that balance their voluntary work at the CHC and MHC with their jobs as subsistence farmers. Their motivation is to find positive solutions to their community’s health‐related problems and to find funding for specific projects they already have underway. However, only the two CHCs that are part of the pilot health promotion plan get invitations to the meetings and the other 47 CHCs do not. According to the institutional stakeholders, there is no need for a personalized invitation to each of them because there is always an open, standing invitation issued out. However, there is no way to ensure that stakeholders know about this invitation, and the next meeting time and place is decided at the end of each meeting. As a result, 47 CHCs, two NGOs and one governmental organization never attend. Another argument for the lack of community‐level participation, according to a municipal stakeholder, was that ‘It is too expensive… [to come to the meetings and] community committees manage their projects ‐and their costs’. The plan is to integrate more representatives from the different communities as the municipality expands the health promotion plan, but it is not clear when more communities will be included or how their representatives will attend the meetings. Community‐level stakeholders feel that more collaboration is needed, as one stakeholder from a CHC pointed out that ‘in every single project and plan that comes from the capital city and from the government they need to involve the municipality, who needs to work with the community leaders. It’s the leaders that can fix problems because people trust us, and by working with the municipality [and the government] we can all move forward’.

When it comes to the responsibilities that the members of the MHC have, the legislation only mandates specific roles for the representatives from the MoH and from the municipal government, and there is no mechanism to ensure the participation of other stakeholders, as well as no set meeting times or frequencies. 18 , 20 , 22 When asked what could be done to improve participation, one stakeholder from the municipality pointed out that ‘we are all committed to the social development process…participation is a professional and moral commitment that communities need to have. Because of this, participation depends on the conviction of the institution’. On the other hand, a stakeholder from the health district recognized the shortcomings of their system and stated ‘like everywhere, there are some people that participate and some that do not. What we need is more communication about what we are doing, what we hope to do and what we need to do it’.

How and where is social participation in the health system taking place?

For the institutional stakeholders, the role they play and the one that community stakeholders have are very different. Institutional stakeholders see themselves as ‘problem‐solvers’ and ‘decision‐makers’ that help to solve the needs that communities identified. One stakeholder from the municipality described the role that institutional and community stakeholders have like this: ‘[community members] play a very important role because without them, we don’t know what they need. We can’t help them or do their paperwork for them. They are very important in this whole process because they know their needs, they tell them to us and then we can take steps to fix their problems’. This stakeholder also added that ‘communities shouldn’t participate in creating programs or making decisions because of their lack of knowledge… The community may provide some ideas, but decisions have to come from professionals’. In the context of the MHC, this means that institutional stakeholders design the policies and CHCs carry them out.

Community‐level stakeholders agree with the institutional stakeholders that their main role is to identify the needs they have in their communities, prioritize them and then seek help with the health district or municipal authorities. However, they also recognize a need for them to be involved in decision‐making processes because, as one community stakeholder stated, ‘you have to have a say. If you don’t, then you can do nothing. If we don’t give our opinion, nothing can be done’. Another community stakeholder stated that ‘the community knows that they chose a [community‐level health] commission to get the job done. That is what we do, identify a need and look for a way to solve it. We weigh the pros and cons, put it in writing and act on it. That is all we can do’. To some extent, the institutional stakeholders agree because as one stakeholder from the health area put it, the goal of participation is to ‘have the people be active agents of change. To have them feel a need and look for alternatives according to their own needs, as well as have them work so that change comes from within their community. To have them be part of the solution, and not the problem’.

What is social participation in health?

For the stakeholders who represent the institutions that work in health in Palencia, social participation within the decentralization process and in the health system is defined in different ways. In the context of decentralization policies, social participation is an empowering process that improves the quality of life of community members through the building of infrastructure, implementation of programmes and policies and building a better relationship between the state and its inhabitants. Its main goal is to empower local communities and individuals so that they can take control of their lives and shape policies according to their needs. It was described as ‘[a process] where communities are active participants in their own development. [Participation is getting everyone involved] in everything from the planning to the execution of the needs they identified as most urgent…the municipality believes in participatory processes that involves community members and allows their views, priorities and perspectives to be integrated into policies’ (stakeholder from the municipality). This way of understanding participation is in line with what the legal framework defines as participation, which is ‘…a process where organized communities participate in the planning, execution and integral control of the governments’policies in order to facilitate the process of decentralization and their own social, economic and cultural development’. 18

However, when it comes to participating in the health system, it is no longer a process where institutions and communities work together. As one stakeholder from the municipality described it, [social participation is a way to]’…try to get people to not be afraid of going to the doctor, because even when institutions want to work with the communities, our own idiosyncrasies and culture restrict us in accepting care from the physician. The first step in participating is to be open to a medical examination…so that they are aware of their needs ’. Another representative from the municipality also added that ‘social participation in health will allow families to have access to the health services that already exist in Palencia’.

For community‐level stakeholders, there is no difference between social participation in the social development process and in the health system. For them, it is ‘grouping together and supporting each other when it comes to health, education, and community development. We all have to work together as a team to know where there are faults and what we could do to mend that’. Specific participatory practices in health, as reported by a member of a CHC, include helping with community organization, with emergency transport for people that are sick and with taking care of the community’s children to keep them healthy.

Discussion

The role that social participation plays in PHC and in many health systems has been studied broadly over the past 30 years. 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 12 , 27 However, most of the focus of the research has been on measuring and promoting participation, and less attention has been paid to how the perspectives and personal motivations of the stakeholders may shape a relatively new process when there are no clear‐cut guidelines or policies that create a solid structure for participation.

Guatemala has a progressive legal framework for social participation, one that aims to redistribute power among the population through decision‐making spaces that tailor national policies to specific needs. The law states that all stakeholders should have the same right for equal participation in the open and democratic spaces for decision making that the decentralization process created. 21 However, the legislation only provides abstract guiding principles and ideals and not specific instructions on how to implement a fair and equal participation process. The Brazilian case shows that having clear regulations with outlined benefits and penalties and easy to follow structures and funds to back up the participatory process can contribute to creating a strong system where the policies provide a way to balance out the personal interests or agendas of the stakeholders. 32 , 33 This can result in achieving a social participation process that is based on the rights of citizens and not just on user expectation. However, the Guatemalan legal framework allows the stakeholders to interpret these policies using their own abilities, agendas and the available resources they have, which leads to each municipality having their own version of what participating in the health commission means.

In Palencia, what social participation is depends on who is participating. Institutional stakeholders have the human, financial and other power resources to make policies based on consensus only between them. During its first year of existence, the MHC has been successfully used in coordinating institutional activities that reflect social participation with a top‐down perspective, and they approach the community‐level stakeholders with a paternalistic stance. Decisions over municipal‐level policies are made among the stakeholders that have the resources to back the policies up, which results in excluding community‐level stakeholders from making any decisions at the municipal‐level health council, even if they are present and attending the meetings. This is because institutional stakeholders see their own role as ‘policy makers’.

In contrast, community‐level stakeholders have a broader perspective and understanding of what participation in health is. For them, group work, joint decision making and sharing information are the key elements to improving their communities’ well‐being in regard to more than just their health status. Social participation is seen as a tool to improve the quality of life of all of the community members and the way to acquire social and economic development projects in place. However, community‐level stakeholders can only use the resources they have (knowledge of their own needs, of the financial, social and cultural situations of their communities, and their social capital) to provide input for the institutional stakeholders to use in their policies and later and to help in the implementation phase.

Despite the differences in their roles in the health commission, our results show that all stakeholders feel that they all have a significant part to play in the social and economic development process of their municipality. To understand why the stakeholders report feeling this way, we must look at both the external differences between the stakeholders and how they internalize and interpret the process and its results. Both groups of stakeholders report feeling that everyone is participating to the extent of not only their abilities, but also of their financial, social and time constraints. To understand this, we must look at both groups’ motivations and roles separately. The institutional stakeholder group has all the decision‐making power and chooses whom to include or exclude from the meetings, which makes them the key players in this process. For them, the internal satisfaction comes from using the municipal‐level health council as a place where they meet to optimize the use of their resources. This results in them feeling like they can provide better care for the population.

The community‐level stakeholders are the token participants of the municipal‐level health council because they lack the kind of resources that allow them to bargain with the institutional stakeholders. 34 From the external perspective, they cannot afford to attend all of the meetings, and they lack the training and the same kind of power resources to be treated as equals in the MHC, so they are assigned a role that is not related to policy‐making. Internally, however, they are satisfied with the process because of the positive changes they see in their communities and from the projects they help to bring in through their own role in the process.

Despite the shortcomings of the process, both groups of stakeholders seem to be comfortable with their roles. There is a long way to go before Palencia’s MHC can achieve the ‘empowerment’ expressed in the legal framework and the kind of participation and community leadership that the PHC approach calls for.

Palencia has a specific context, one that might not apply to the majority of municipalities in Guatemala. Additionally, because we only followed the work of the MHC during its first year of functioning, we do not know if the current dynamic will be manifested over time or if it is a reflection of it being in its initiation phase.

Conclusion

Guatemala’s progressive but abstract legal framework on social participation created open spaces for discussing, formulating and implementing policies. At the same time, the decentralization process and the social development council scheme provided tools that municipal‐level stakeholders use to tailor national policies to their own needs.

Palencia’s case demonstrates that the different power resources that the stakeholders have contribute to creating different but often complementary roles within the participatory process. By analysing these roles, we show that most of the decisions on policy fall on the institutional stakeholders and much of the implementation activities for these policies fall on the community‐level stakeholders. As a result, the empowerment of community stakeholders and their participation in policy‐making and not just in policy implementation remains limited. Because the national policies are so abstract, each municipality can interpret and adapt them to fit the agenda of the stakeholders that have more power.

The process of social participation in MHC should be one that helps to increase the decision‐making capacity of the community stakeholders, so that they can contribute to the reformulation of national health policies to fit the municipality’s needs, priorities and resources. Clear‐cut guidelines and regulations on how to achieve and maintain an equal and fair participatory process for making decisions are required. In addition to this, the implementation of a monitoring system that can reward participation by assigning extra resources could be helpful in maintaining the continuity of the process. As a result of more uniformed mechanisms and incentives, the development process will be less fragmented and not depend on each of the individual stakeholders’ good will.

Sources of funding

This work was undertaken within the Centre for Global Health Research, at Umeå University, with support from FAS, the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (grant no, 2006‐1512).

Conflicts of interest

We declare we have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Alison Hérnandez and Alejandro Echeverría for their valuable comments on earlier verisons of this manuscript. We are also grateful to all the members of Palencia’s municipal‐level health commission.

References

- 1. Zakus D, Lysak CL. Revisiting community participation. Health Policy and Planning, 1998; 13: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO/UNICEF . Primary Health Care. Report of the International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma‐Ata. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1978: 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO . Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever. World health report. Geneva: WHO, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flores W, Ruano AL. Atención primaria en salud y participación social: análisis del contexto histórico de América Latina, de los desafíos actuales y las oportunidades existentes In: Salud para todos: una meta posible. Buenos Aires: IIED Publicaciones para América Latina, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Welschhoff A. Community participation and primary health care in India. Disertation der Fakultät für Geowissenschaffen der Universitët München, 2006.

- 6. Rifkin S, Muller F, Bichman W. Primary health care: on measuring participation. Social Science and Medicine, 1998; 26: 931–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gaventa J, Valderrama C. Participation, Citizenship and Governance. Background Note Prepared for Workshop on Strengthening Participation in Local Governance. : IDS, 1999. Available at: http://www.uv.es/~fernandm/Gaventa,%20Valderrama.pdf, accessed 15 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hooghe L, Marks G. Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of multi‐level governance The American Political Science Review, 2003; 97: 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson C. Local democracy, democratic decentralization and rural development: theories, challenges and options for policy. Development Policy Review, 2001; 19: 521–532. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mosquera M, Zapata Y, Lee K, Arango C, Varela A. Strengthening user participation through health sector reform in Colombia: a study of institutional change and social representation. Health Policy and Planning, 2001; 16 (Suppl 2): 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cornwall A, Gaventa J. From Users and Choosers to Makers and Shapers: Repositioning Participation in Social Policy. Brighton: Eldis.org, 2001. Available at: http://www.eldis.org/vfile/upload/1/document/0708/DOC2894.pdf, accessed 5 March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ugalde A. Ideological dimensions of community participation in Latin American health programs’. Social Science and Medicine, 1985; 21: 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rull M. Los caminos del desarrollo en Guatemala: democratización versus globalización o el nuevo desencuentro de dos mundos, 2007. Available at: http://www.cemca‐ac.org/docs/mRull%20‐%20Democracia%20y%20Desarrollo%20en%20Guatemala,%20Congreso%20Barcelona%200907.pdf, accessed 5 March 2010.

- 14. Cruz González C. Fortalecimiento de la organización comunitaria (COCODES y COMUDE) de la municipalidad de San Bartolomé Milpas Altas, Sacatepéquez. Guatemala: Universidad Rafael Landívar, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15. INE . Características de la población y de los locales de habitación censados. Guatemala: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16. INE . Mapas de pobreza en Guatemala: un auxiliar para entender el flagelo de la pobreza en el país. Guatemala: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Bank . World Development Report: Equity and Development. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18. CONGRESO de la República de Guatemala . Ley de consejos del desarrollo urbano y rural. Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19. MINUGUA . Los acuerdos de paz. Misión de verificación de las Naciones Unidas en Guatemala, 2004. Available at: http://www.minugua.guate.net/ACUERDOSDEPAZ/ACUERDOSESPA%D1OL/AC%20SOCIOECONOMICO.htm, accessed 17 May 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Congreso de la República de Guatemala . Código Municipal. Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Congreso de la República de Guatemala . Ley de descentralización. Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pérez A. Políticas públicas, poder local y participación ciudadana en el sistema de consejos de desarrollo urbano y rural. Guatemala: AVANCSO, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Congreso de la República de Guatemala . Código de salud. Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martínez H, Cifuentes NI. Proceso de la organización y capacitación de comisiones de salud para la implementación de planes de emergencia. Informe de sistematización de la experiencia, Guatemala, 2007.

- 25. ENCOVI . Encuesta Nacional de Condiciones de Vida. Guatemala: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Municipalidad de Palencia . Datos generales del municipio. 2009. Available at: http://www.munipalencia.com/datos.htm, accessed 12 February 2009.

- 27. Rifkin S. Lessons from community participation in health programs. Health Policy and Planning, 1986; 1: 240–249. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Congreso de la República de Guatemala . Ley de desarrollo social. Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Congreso de la República de Guatemala . Constitución Política de la República de Guatemala. Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Robson C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientist and Practitioner‐Researchers. UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd edn Beverly Hills: SAGE, 2004. Available at: http://www.ies.luth.se/es/Forskarkurser/Methodcourse/From_Miles_Huberman.pdf, accessed 22 January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barnes M, Schattan V. Social participation in health in Brazil and England: inclusion, representation and authority. Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 226–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Elias PEM, Cohn A. Health reform in Brazil: lessons to consider. American Journal of Public Health, 2003; 93: 44–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Collins C, Araujo J, Barbosa J. Decentralizing the health sector: issues in Brazil. Health Policy, 2000; 52: 113–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]